Abyssal Plain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An abyssal plain is an underwater

An abyssal plain is an underwater

The ocean can be conceptualized as zones, depending on depth, and presence or absence of

The ocean can be conceptualized as zones, depending on depth, and presence or absence of

Oceanic crust, which forms the bedrock of abyssal plains, is continuously being created at mid-ocean ridges (a type of divergent boundary) by a process known as decompression melting. Plume-related decompression melting of solid mantle is responsible for creating ocean islands like the Hawaiian islands, as well as the ocean crust at mid-ocean ridges. This phenomenon is also the most common explanation for

Oceanic crust, which forms the bedrock of abyssal plains, is continuously being created at mid-ocean ridges (a type of divergent boundary) by a process known as decompression melting. Plume-related decompression melting of solid mantle is responsible for creating ocean islands like the Hawaiian islands, as well as the ocean crust at mid-ocean ridges. This phenomenon is also the most common explanation for

Mantle Convection

. Physics Department, University of Winnipeg. Retrieved 23 June 2010. The

The landmark scientific expedition (December 1872 – May 1876) of the British

The landmark scientific expedition (December 1872 – May 1876) of the British

station 225

The reported depth was 4,475 fathoms (8184 meters) based on two separate soundings. On 1 June 2009, sonar mapping of the Challenger Deep by the Simrad EM120 multibeam sonar bathymetry system aboard the R/V ''Kilo Moana'' indicated a maximum depth of 10971 meters (6.82 miles). The sonar system uses phase and amplitude bottom detection, with an accuracy of better than 0.2% of water depth (this is an error of about 22 meters at this depth).

A rare but important terrain feature found in the bathyal, abyssal and hadal zones is the hydrothermal vent. In contrast to the approximately 2 °C ambient water temperature at these depths, water emerges from these vents at temperatures ranging from 60 °C up to as high as 464 °C. Due to the high barometric pressure at these depths, water may exist in either its liquid form or as a supercritical fluid at such temperatures.

At a barometric pressure of 218 atmospheres, the critical point of water is 375 °C. At a depth of 3,000 meters, the barometric pressure of sea water is more than 300 atmospheres (as salt water is denser than fresh water). At this depth and pressure, seawater becomes supercritical at a temperature of 407 °C (''see image''). However the increase in salinity at this depth pushes the water closer to its critical point. Thus, water emerging from the hottest parts of some hydrothermal vents, '' black smokers'' and submarine volcanoes can be a supercritical fluid, possessing physical properties between those of a gas and those of a

A rare but important terrain feature found in the bathyal, abyssal and hadal zones is the hydrothermal vent. In contrast to the approximately 2 °C ambient water temperature at these depths, water emerges from these vents at temperatures ranging from 60 °C up to as high as 464 °C. Due to the high barometric pressure at these depths, water may exist in either its liquid form or as a supercritical fluid at such temperatures.

At a barometric pressure of 218 atmospheres, the critical point of water is 375 °C. At a depth of 3,000 meters, the barometric pressure of sea water is more than 300 atmospheres (as salt water is denser than fresh water). At this depth and pressure, seawater becomes supercritical at a temperature of 407 °C (''see image''). However the increase in salinity at this depth pushes the water closer to its critical point. Thus, water emerging from the hottest parts of some hydrothermal vents, '' black smokers'' and submarine volcanoes can be a supercritical fluid, possessing physical properties between those of a gas and those of a

here

Eleven of the 31 described species of '' Monoplacophora'' (a

plain

In geography, a plain, commonly known as flatland, is a flat expanse of land that generally does not change much in elevation, and is primarily treeless. Plains occur as lowlands along valleys or at the base of mountains, as coastal plains, and ...

on the deep ocean floor, usually found at depths between . Lying generally between the foot of a continental rise and a mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a undersea mountain range, seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading ...

, abyssal plains cover more than 50% of the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

's surface. They are among the flattest, smoothest, and least explored regions on Earth. Abyssal plains are key geologic elements of oceanic basins, the other elements being an elevated mid-ocean ridge and flanking abyssal hills.

The creation of the abyssal plain is the result of the spreading of the seafloor (plate tectonics) and the melting of the lower oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

. Magma rises from above the asthenosphere (a layer of the upper mantle), and as this basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

ic material reaches the surface at mid-ocean ridges, it forms new oceanic crust, which is constantly pulled sideways by spreading of the seafloor. Abyssal plains result from the blanketing of an originally uneven surface of oceanic crust by fine-grained sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

s, mainly clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

and silt. Much of this sediment is deposited by turbidity currents that have been channelled from the continental margins along submarine canyons into deeper water. The rest is composed chiefly of pelagic sediments. Metallic nodules are common in some areas of the plains, with varying concentrations of metals, including manganese

Manganese is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese was first isolated in the 1770s. It is a transition m ...

, iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, nickel, cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. ...

, and copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

. There are also amounts of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and silicon, due to material that comes down and decomposes.

Owing in part to their vast size, abyssal plains are believed to be major reservoirs of biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variability of life, life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and Phylogenetics, phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distribut ...

. They also exert significant influence upon ocean carbon cycling, dissolution of calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

, and atmospheric CO2 concentrations over time scales of a hundred to a thousand years. The structure of abyssal ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s is strongly influenced by the rate of flux of food to the seafloor and the composition of the material that settles. Factors such as climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

, fishing practices, and ocean fertilization have a substantial effect on patterns of primary production in the euphotic zone. Animals absorb dissolved oxygen from the oxygen-poor waters. Much dissolved oxygen in abyssal plains came from polar regions that had melted long ago. Due to scarcity of oxygen, abyssal plains are inhospitable for organisms that would flourish in the oxygen-enriched waters above. Deep sea coral reefs are mainly found in depths of 3,000 meters and deeper in the abyssal and hadal zones.

Abyssal plains were not recognized as distinct physiographic features of the sea floor until the late 1940s and, until recently, none had been studied on a systematic basis. They are poorly preserved in the sedimentary record, because they tend to be consumed by the subduction process. Due to darkness and a water pressure that can reach about 750 times atmospheric pressure (76 megapascal), abyssal plains are not well explored.

Oceanic zones

sunlight

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible spectrum, visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrare ...

. Nearly all life forms in the ocean depend on the photosynthetic

Photosynthesis ( ) is a Biological system, system of biological processes by which Photoautotrophism, photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical ener ...

activities of phytoplankton and other marine plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s to convert carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

into organic carbon, which is the basic building block of organic matter. Photosynthesis in turn requires energy from sunlight to drive the chemical reactions that produce organic carbon.

The stratum of the water column nearest the surface of the ocean (sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

) is referred to as the photic zone. The photic zone can be subdivided into two different vertical regions. The uppermost portion of the photic zone, where there is adequate light to support photosynthesis by phytoplankton and plants, is referred to as the euphotic zone (also referred to as the '' epipelagic zone'', or ''surface zone''). The lower portion of the photic zone, where the light intensity is insufficient for photosynthesis, is called the dysphotic zone (dysphotic means "poorly lit" in Greek). The dysphotic zone is also referred to as the ''mesopelagic zone'', or the ''twilight zone''. Its lowermost boundary is at a thermocline of , which, in the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

generally lies between 200 and 1,000 metres.

The euphotic zone is somewhat arbitrarily defined as extending from the surface to the depth where the light intensity is approximately 0.1–1% of surface sunlight irradiance, depending on season

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's axial tilt, tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperat ...

, latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

and degree of water turbidity. In the clearest ocean water, the euphotic zone may extend to a depth of about 150 metres, or rarely, up to 200 metres. Dissolved substances and solid particles absorb and scatter light, and in coastal regions the high concentration of these substances causes light to be attenuated rapidly with depth. In such areas the euphotic zone may be only a few tens of metres deep or less. The dysphotic zone, where light intensity is considerably less than 1% of surface irradiance, extends from the base of the euphotic zone to about 1,000 metres. Extending from the bottom of the photic zone down to the seabed is the aphotic zone, a region of perpetual darkness.

Since the average depth of the ocean is about 4,300 metres, the photic zone represents only a tiny fraction of the ocean's total volume. However, due to its capacity for photosynthesis, the photic zone has the greatest biodiversity and biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

of all oceanic zones. Nearly all primary production in the ocean occurs here. Life forms which inhabit the aphotic zone are often capable of movement upwards through the water column into the photic zone for feeding. Otherwise, they must rely on material sinking from above, or find another source of energy and nutrition, such as occurs in chemosynthetic archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

found near hydrothermal vents and cold seeps.

The aphotic zone can be subdivided into three different vertical regions, based on depth and temperature. First is the bathyal zone, extending from a depth of 1,000 metres down to 3,000 metres, with water temperature decreasing from to as depth increases. Next is the abyssal zone, extending from a depth of 3,000 metres down to 6,000 metres. The final zone includes the deep oceanic trenches, and is known as the hadal zone. This, the deepest oceanic zone, extends from a depth of 6,000 metres down to approximately 11,034 meters, at the very bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest point on planet Earth. Abyssal plains are typically in the abyssal zone, at depths from 3,000 to 6,000 metres.

The table below illustrates the classification of oceanic zones:

Formation

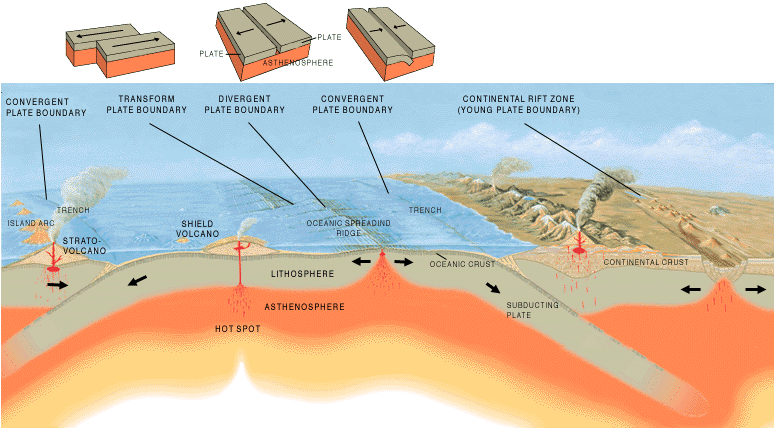

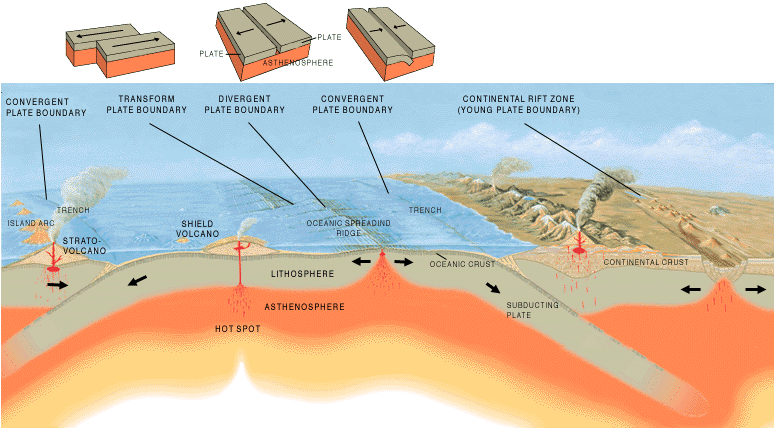

Oceanic crust, which forms the bedrock of abyssal plains, is continuously being created at mid-ocean ridges (a type of divergent boundary) by a process known as decompression melting. Plume-related decompression melting of solid mantle is responsible for creating ocean islands like the Hawaiian islands, as well as the ocean crust at mid-ocean ridges. This phenomenon is also the most common explanation for

Oceanic crust, which forms the bedrock of abyssal plains, is continuously being created at mid-ocean ridges (a type of divergent boundary) by a process known as decompression melting. Plume-related decompression melting of solid mantle is responsible for creating ocean islands like the Hawaiian islands, as well as the ocean crust at mid-ocean ridges. This phenomenon is also the most common explanation for flood basalt

A flood basalt (or plateau basalt) is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Many flood basalts have been attributed to the onset of a hotspot (geolo ...

s and oceanic plateaus (two types of large igneous provinces). Decompression melting occurs when the upper mantle is partially melted into magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma (sometimes colloquially but incorrectly referred to as ''lava'') is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also ...

as it moves upwards under mid-ocean ridges. This upwelling magma then cools and solidifies by conduction and convection

Convection is single or Multiphase flow, multiphase fluid flow that occurs Spontaneous process, spontaneously through the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoy ...

of heat to form new oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

. Accretion occurs as mantle is added to the growing edges of a tectonic plate, usually associated with seafloor spreading. The age of oceanic crust is therefore a function of distance from the mid-ocean ridge. The youngest oceanic crust is at the mid-ocean ridges, and it becomes progressively older, cooler and denser as it migrates outwards from the mid-ocean ridges as part of the process called mantle convection.Kobes, Randy and Kunstatter, GaboMantle Convection

. Physics Department, University of Winnipeg. Retrieved 23 June 2010. The

lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the lithospheric mantle, the topmost portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time ...

, which rides atop the asthenosphere, is divided into a number of tectonic plates that are continuously being created and consumed at their opposite plate boundaries. Oceanic crust and tectonic plates are formed and move apart at mid-ocean ridges. Abyssal hills are formed by stretching of the oceanic lithosphere. Consumption or destruction of the oceanic lithosphere occurs at oceanic trenches (a type of convergent boundary

A convergent boundary (also known as a destructive boundary) is an area on Earth where two or more lithospheric plates collide. One plate eventually slides beneath the other, a process known as subduction. The subduction zone can be defined by a ...

, also known as a destructive plate boundary) by a process known as subduction. Oceanic trenches are found at places where the oceanic lithospheric slabs of two different plates meet, and the denser (older) slab begins to descend back into the mantle. At the consumption edge of the plate (the oceanic trench), the oceanic lithosphere has thermally contracted to become quite dense, and it sinks under its own weight in the process of subduction.

The subduction process consumes older oceanic lithosphere, so oceanic crust is seldom more than 200 million years old. The overall process of repeated cycles of creation and destruction of oceanic crust is known as the Supercontinent cycle, first proposed by Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

geophysicist and geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the structure, composition, and History of Earth, history of Earth. Geologists incorporate techniques from physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and geography to perform research in the Field research, ...

John Tuzo Wilson.

New oceanic crust, closest to the mid-oceanic ridges, is mostly basalt at shallow levels and has a rugged topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

. The roughness of this topography is a function of the rate at which the mid-ocean ridge is spreading (the spreading rate). Magnitudes of spreading rates vary quite significantly. Typical values for fast-spreading ridges are greater than 100 mm/yr, while slow-spreading ridges are typically less than 20 mm/yr. Studies have shown that the slower the spreading rate, the rougher the new oceanic crust will be, and vice versa. It is thought this phenomenon is due to faulting at the mid-ocean ridge when the new oceanic crust was formed. These faults pervading the oceanic crust, along with their bounding abyssal hills, are the most common tectonic and topographic features on the surface of the Earth. The process of seafloor spreading helps to explain the concept of continental drift in the theory of plate tectonics.

The flat appearance of mature abyssal plains results from the blanketing of this originally uneven surface of oceanic crust by fine-grained sediments, mainly clay and silt. Much of this sediment is deposited from turbidity currents that have been channeled from the continental margins along submarine canyons down into deeper water. The remainder of the sediment comprises chiefly dust (clay particles) blown out to sea from land, and the remains of small marine plants and animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ...

which sink from the upper layer of the ocean, known as pelagic sediments. The total sediment deposition rate in remote areas is estimated at two to three centimeters per thousand years. Sediment-covered abyssal plains are less common in the Pacific Ocean than in other major ocean basins because sediments from turbidity currents are trapped in oceanic trenches that border the Pacific Ocean.

Abyssal plains are typically covered by deep sea, but during parts of the Messinian salinity crisis much of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

's abyssal plain was exposed to air as an empty deep hot dry salt-floored sink.

Discovery

The landmark scientific expedition (December 1872 – May 1876) of the British

The landmark scientific expedition (December 1872 – May 1876) of the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

survey ship HMS ''Challenger'' yielded a tremendous amount of bathymetric data, much of which has been confirmed by subsequent researchers. Bathymetric data obtained during the course of the Challenger expedition enabled scientists to draw maps, which provided a rough outline of certain major submarine terrain features, such as the edge of the continental shelves and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a Divergent boundary, divergent or constructive Plate tectonics, plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest mountai ...

. This discontinuous set of data points was obtained by the simple technique of taking soundings by lowering long lines from the ship to the seabed.

The Challenger expedition was followed by the 1879–1881 expedition of the ''Jeannette'', led by United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

Lieutenant George Washington DeLong. The team sailed across the Chukchi Sea and recorded meteorological and astronomical

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest include ...

data in addition to taking soundings of the seabed. The ship became trapped in the ice pack near Wrangel Island in September 1879, and was ultimately crushed and sunk in June 1881.

The ''Jeannette'' expedition was followed by the 1893–1896 Arctic expedition of Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen aboard the '' Fram'', which proved that the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

was a deep oceanic basin, uninterrupted by any significant land masses north of the Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

n continent.

Beginning in 1916, Canadian physicist Robert William Boyle and other scientists of the Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee ( ASDIC) undertook research which ultimately led to the development of sonar technology. Acoustic sounding equipment was developed which could be operated much more rapidly than the sounding lines, thus enabling the German Meteor expedition aboard the German research vessel Meteor

A meteor, known colloquially as a shooting star, is a glowing streak of a small body (usually meteoroid) going through Earth's atmosphere, after being heated to incandescence by collisions with air molecules in the upper atmosphere,

creating a ...

(1925–27) to take frequent soundings on east-west Atlantic transects. Maps produced from these techniques show the major Atlantic basins, but the depth precision of these early instruments was not sufficient to reveal the flat featureless abyssal plains.

As technology improved, measurement of depth, latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

and longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

became more precise and it became possible to collect more or less continuous sets of data points. This allowed researchers to draw accurate and detailed maps of large areas of the ocean floor. Use of a continuously recording fathometer enabled Tolstoy & Ewing in the summer of 1947 to identify and describe the first abyssal plain. This plain, south of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, is now known as the Sohm Abyssal Plain. Following this discovery many other examples were found in all the oceans.

The Challenger Deep

The Challenger Deep is the List of submarine topographical features#List of oceanic trenches, deepest known point of the seabed of Earth, located in the western Pacific Ocean at the southern end of the Mariana Trench, in the ocean territory o ...

is the deepest surveyed point of all of Earth's oceans; it is at the south end of the Mariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deep sea, deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about in length and in width. The maxi ...

near the Mariana Islands group. The depression is named after HMS ''Challenger'', whose researchers made the first recordings of its depth on 23 March 1875 astation 225

The reported depth was 4,475 fathoms (8184 meters) based on two separate soundings. On 1 June 2009, sonar mapping of the Challenger Deep by the Simrad EM120 multibeam sonar bathymetry system aboard the R/V ''Kilo Moana'' indicated a maximum depth of 10971 meters (6.82 miles). The sonar system uses phase and amplitude bottom detection, with an accuracy of better than 0.2% of water depth (this is an error of about 22 meters at this depth).

Terrain features

Hydrothermal vents

liquid

Liquid is a state of matter with a definite volume but no fixed shape. Liquids adapt to the shape of their container and are nearly incompressible, maintaining their volume even under pressure. The density of a liquid is usually close to th ...

.

''Sister Peak'' (Comfortless Cove Hydrothermal Field, , elevation −2996 m), ''Shrimp Farm'' and ''Mephisto'' (Red Lion Hydrothermal Field, , elevation −3047 m), are three hydrothermal vents of the black smoker category, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge near Ascension Island. They are presumed to have been active since an earthquake shook the region in 2002. These vents have been observed to vent phase-separated, vapor-type fluids. In 2008, sustained exit temperatures of up to 407 °C were recorded at one of these vents, with a peak recorded temperature of up to 464 °C. These thermodynamic conditions exceed the critical point of seawater, and are the highest temperatures recorded to date from the seafloor. This is the first reported evidence for direct magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma (sometimes colloquially but incorrectly referred to as ''lava'') is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also ...

tic- hydrothermal interaction on a slow-spreading mid-ocean ridge. The initial stages of a vent chimney begin with the deposition of the mineral anhydrite. Sulfides of copper, iron, and zinc then precipitate in the chimney gaps, making it less porous over the course of time. Vent growths on the order of 30 cm (1 ft) per day have been recorded. 1An April 2007 exploration of the deep-sea vents off the coast of Fiji found those vents to be a significant source of dissolved iron (see iron cycle).

Hydrothermal vents in the deep ocean typically form along the mid-ocean ridges, such as the East Pacific Rise and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. These are locations where two tectonic plates are diverging and new crust is being formed.

Cold seeps

Another unusual feature found in the abyssal and hadal zones is the cold seep, sometimes called a ''cold vent''. This is an area of the seabed where seepage ofhydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

, methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

and other hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and Hydrophobe, hydrophobic; their odor is usually fain ...

-rich fluid occurs, often in the form of a deep-sea brine pool. The first cold seeps were discovered in 1983, at a depth of 3200 meters in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

. Since then, cold seeps have been discovered in many other areas of the World Ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Antarctic/Southern, and ...

, including the Monterey Submarine Canyon just off Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by about 75 miles (120 km), accessible via California S ...

, California, the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it ...

, off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

, off the Atlantic coast of Africa, off the coast of Alaska, and under an ice shelf in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

.

Biodiversity

Though the plains were once assumed to be vast,desert

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the la ...

-like habitats, research over the past decade or so shows that they teem with a wide variety of microbial life. However, ecosystem structure and function at the deep seafloor have historically been poorly studied because of the size and remoteness of the abyss. Recent oceanographic expeditions conducted by an international group of scientists from the Census of Diversity of Abyssal Marine Life (CeDAMar) have found an extremely high level of biodiversity on abyssal plains, with up to 2000 species of bacteria, 250 species of protozoans, and 500 species of invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s ( worms, crustaceans and molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

), typically found at single abyssal sites. New species make up more than 80% of the thousands of seafloor invertebrate species collected at any abyssal station, highlighting our heretofore poor understanding of abyssal diversity and evolution. Richer biodiversity is associated with areas of known phytodetritus input and higher organic carbon flux.

'' Abyssobrotula galatheae'', a species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of cusk eel in the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Ophidiidae, is among the deepest-living species of fish. In 1970, one specimen was trawled from a depth of 8370 meters in the Puerto Rico Trench. The animal was dead, however, upon arrival at the surface. In 2008, the hadal snailfish (''Pseudoliparis amblystomopsis'') was observed and recorded at a depth of 7700 meters in the Japan Trench. In December 2014 a type of snailfish was filmed at a depth of 8145 meters, followed in May 2017 by another sailfish filmed at 8178 meters. These are, to date, the deepest living fish ever recorded. Other fish of the abyssal zone include the fishes of the family Ipnopidae, which includes the abyssal spiderfish ('' Bathypterois longipes''), tripodfish ('' Bathypterois grallator''), feeler fish ('' Bathypterois longifilis''), and the black lizardfish ('' Bathysauropsis gracilis''). Some members of this family have been recorded from depths of more than 6000 meters.

CeDAMar scientists have demonstrated that some abyssal and hadal species have a cosmopolitan distribution. One example of this would be protozoan foraminifera

Foraminifera ( ; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are unicellular organism, single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class (biology), class of Rhizarian protists characterized by streaming granular Ectoplasm (cell bio ...

ns, certain species of which are distributed from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Other faunal groups, such as the polychaete worms and isopod crustaceans, appear to be endemic to certain specific plains and basins. Many apparently unique taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

of nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

worms have also been recently discovered on abyssal plains. This suggests that the deep ocean has fostered adaptive radiations. The taxonomic composition of the nematode fauna in the abyssal Pacific is similar, but not identical to, that of the North Atlantic. A list of some of the species that have been discovered or redescribed by CeDAMar can be founhere

Eleven of the 31 described species of '' Monoplacophora'' (a

class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

of mollusks) live below 2000 meters. Of these 11 species, two live exclusively in the hadal zone. The greatest number of monoplacophorans are from the eastern Pacific Ocean along the oceanic trenches. However, no abyssal monoplacophorans have yet been found in the Western Pacific and only one abyssal species has been identified in the Indian Ocean. Of the 922 known species of chitons (from the '' Polyplacophora'' class of mollusks), 22 species (2.4%) are reported to live below 2000 meters and two of them are restricted to the abyssal plain. Although genetic studies are lacking, at least six of these species are thought to be eurybathic (capable of living in a wide range of depths), having been reported as occurring from the sublittoral to abyssal depths. A large number of the polyplacophorans from great depths are herbivorous or xylophagous, which could explain the difference between the distribution of monoplacophorans and polyplacophorans in the world's oceans.

Peracarid crustaceans, including isopods, are known to form a significant part of the macrobenthic community that is responsible for scavenging on large food falls onto the sea floor. In 2000, scientists of the ''Diversity of the deep Atlantic benthos'' (DIVA 1) expedition (cruise M48/1 of the German research vessel RV ''Meteor III'') discovered and collected three new species of the Asellota suborder of benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

isopods from the abyssal plains of the Angola Basin in the South Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

. In 2003, De Broyer et al. collected some 68,000 peracarid crustaceans from 62 species from baited traps deployed in the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha C ...

, Scotia Sea, and off the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands, Antarctic islands located in the Drake Passage with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the n ...

. They found that about 98% of the specimens belonged to the amphipod superfamily '' Lysianassoidea'', and 2% to the isopod family Cirolanidae. Half of these species were collected from depths of greater than 1000 meters.

In 2005, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) remotely operated vehicle, KAIKO, collected sediment core from the Challenger Deep. 432 living specimens of soft-walled foraminifera were identified in the sediment samples. Foraminifera are single-celled protist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

s that construct shells. There are an estimated 4,000 species of living foraminifera. Out of the 432 organisms collected, the overwhelming majority of the sample consisted of simple, soft-shelled foraminifera, with others representing species of the complex, multi-chambered genera '' Leptohalysis'' and '' Reophax''. Overall, 85% of the specimens consisted of soft-shelled allogromiids. This is unusual compared to samples of sediment-dwelling organisms from other deep-sea environments, where the percentage of organic-walled foraminifera ranges from 5% to 20% of the total. Small organisms with hard calciferous shells have trouble growing at extreme depths because the water at that depth is severely lacking in calcium carbonate. The giant (5–20 cm) foraminifera known as xenophyophores are only found at depths of 500–10,000 metres, where they can occur in great numbers and greatly increase animal diversity due to their bioturbation and provision of living habitat for small animals.

While similar lifeforms have been known to exist in shallower oceanic trenches (>7,000 m) and on the abyssal plain, the lifeforms discovered in the Challenger Deep may represent independent taxa from those shallower ecosystems. This preponderance of soft-shelled organisms at the Challenger Deep may be a result of selection pressure. Millions of years ago, the Challenger Deep was shallower than it is now. Over the past six to nine million years, as the Challenger Deep grew to its present depth, many of the species present in the sediment of that ancient biosphere were unable to adapt to the increasing water pressure and changing environment. Those species that were able to adapt may have been the ancestors of the organisms currently endemic to the Challenger Deep.

Polychaetes occur throughout the Earth's oceans at all depths, from forms that live as plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

near the surface, to the deepest oceanic trenches. The robot ocean probe Nereus observed a 2–3 cm specimen (still unclassified) of polychaete at the bottom of the Challenger Deep on 31 May 2009. There are more than 10,000 described species of polychaetes; they can be found in nearly every marine environment. Some species live in the coldest ocean temperatures of the hadal zone, while others can be found in the extremely hot waters adjacent to hydrothermal vents.

Within the abyssal and hadal zones, the areas around submarine hydrothermal vents and cold seeps have by far the greatest biomass and biodiversity per unit area. Fueled by the chemicals dissolved in the vent fluids, these areas are often home to large and diverse communities of thermophilic

A thermophile is a type of extremophile that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though some of them are bacteria and fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earliest bact ...

, halophilic

A halophile (from the Greek word for 'salt-loving') is an extremophile that thrives in high salt concentrations. In chemical terms, halophile refers to a Lewis acidic species that has some ability to extract halides from other chemical species.

...

and other extremophilic prokaryotic microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s (such as those of the sulfide-oxidizing genus '' Beggiatoa''), often arranged in large bacterial mats near cold seeps. In these locations, chemosynthetic archaea and bacteria typically form the base of the food chain. Although the process of chemosynthesis is entirely microbial, these chemosynthetic microorganisms often support vast ecosystems consisting of complex multicellular organisms through symbiosis

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

. These communities are characterized by species such as vesicomyid clams, mytilid mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s, limpets, isopods, giant tube worms, soft corals, eelpouts, galatheid crabs, and alvinocarid shrimp. The deepest seep community discovered thus far is in the Japan Trench, at a depth of 7700 meters.

Probably the most important ecological characteristic of abyssal ecosystems is energy limitation. Abyssal seafloor communities are considered to be ''food limited'' because benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

production depends on the input of detrital organic material produced in the euphotic zone, thousands of meters above.Smith, C.R. and Demoupolos, A.W.J. (2003) Ecology of the Pacific ocean floor. In: Ecosystems of the World (Tyler, P.A., ed.), pp. 179–218, Elsevier Most of the organic flux arrives as an attenuated rain of small particles (typically, only 0.5–2% of net primary production in the euphotic zone), which decreases inversely with water depth. The small particle flux can be augmented by the fall of larger carcasses and downslope transport of organic material near continental margins.

Exploitation of resources

In addition to their high biodiversity, abyssal plains are of great current and future commercial and strategic interest. For example, they may be used for the legal and illegal disposal of large structures such as ships and oil rigs,radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. It is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, nuclear decommissioning, rare-earth mining, and nuclear ...

and other hazardous waste

Hazardous waste is waste that must be handled properly to avoid damaging human health or the environment. Waste can be hazardous because it is Toxicity, toxic, Chemical reaction, reacts violently with other chemicals, or is Corrosion, corrosive, ...

, such as munitions. They may also be attractive sites for deep-sea fishing, and extraction of oil and gas and other minerals. Future deep-sea waste disposal

Waste management or waste disposal includes the processes and actions required to manage waste from its inception to its final Waste disposal, disposal. This includes the Waste collection, collection, transport, Sewage treatment, treatm ...

activities that could be significant by 2025 include emplacement of sewage and sludge, carbon sequestration, and disposal of dredge spoils.

As fish stocks dwindle in the upper ocean, deep-sea fisheries are increasingly being targeted for exploitation. Because deep sea fish are long-lived and slow growing, these deep-sea fisheries are not thought to be sustainable in the long term given current management practices. Changes in primary production in the photic zone are expected to alter the standing stocks in the food-limited aphotic zone.

Hydrocarbon exploration in deep water occasionally results in significant environmental degradation

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, referring respectively to all living and non-living things occurring naturally and the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism ...

resulting mainly from accumulation of contaminated drill cuttings, but also from oil spill

An oil spill is the release of a liquid petroleum hydrocarbon into the environment, especially the marine ecosystem, due to human activity, and is a form of pollution. The term is usually given to marine oil spills, where oil is released into th ...

s. While the oil blowout involved in the Deepwater Horizon oil spill

The ''Deepwater Horizon'' oil spill was an environmental disaster off the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico, on the BP-operated Macondo Prospect. It is considered the largest marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum in ...

in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

originates from a wellhead only 1500 meters below the ocean surface, it nevertheless illustrates the kind of environmental disaster that can result from mishaps related to offshore drilling for oil and gas.

Sediments of certain abyssal plains contain abundant mineral resources, notably polymetallic nodules. These potato-sized concretions of manganese, iron, nickel, cobalt, and copper, distributed on the seafloor at depths of greater than 4000 meters, are of significant commercial interest. The area of maximum commercial interest for polymetallic nodule mining (called the Pacific nodule province) lies in international waters

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed region ...

of the Pacific Ocean, stretching from 118°–157°, and from 9°–16°N, an area of more than 3 million km2. The abyssal Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone (CCFZ) is an area within the Pacific nodule province that is currently under exploration for its mineral potential.

Eight commercial contractors are currently licensed by the International Seabed Authority (an intergovernmental organization

Globalization is social change associated with increased connectivity among societies and their elements and the explosive evolution of transportation and telecommunication technologies to facilitate international cultural and economic exchange. ...

established to organize and control all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area beyond the limits of national jurisdiction) to explore nodule resources and to test mining techniques in eight claim areas, each covering 150,000 km2. When mining ultimately begins, each mining operation is projected to directly disrupt 300–800 km2 of seafloor per year and disturb the benthic fauna over an area 5–10 times that size due to redeposition of suspended sediments. Thus, over the 15-year projected duration of a single mining operation, nodule mining might severely damage abyssal seafloor communities over areas of 20,000 to 45,000 km2 (a zone at least the size of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

).

Limited knowledge of the taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

, biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the species distribution, distribution of species and ecosystems in geography, geographic space and through evolutionary history of life, geological time. Organisms and biological community (ecology), communities o ...

and natural history of deep sea communities prevents accurate assessment of the risk of species extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

s from large-scale mining. Data acquired from the abyssal North Pacific and North Atlantic suggest that deep-sea ecosystems may be adversely affected by mining operations on decadal time scales. In 1978, a dredge aboard the Hughes Glomar Explorer, operated by the American mining consortium

A consortium () is an association of two or more individuals, companies, organizations, or governments (or any combination of these entities) with the objective of participating in a common activity or pooling their resources for achieving a ...

Ocean Minerals Company (OMCO), made a mining track at a depth of 5000 meters in the nodule fields of the CCFZ. In 2004, the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea ( IFREMER) conducted the ''Nodinaut'' expedition to this mining track (which is still visible on the seabed) to study the long-term effects of this physical disturbance on the sediment and its benthic fauna. Samples taken of the superficial sediment revealed that its physical and chemical properties had not shown any recovery since the disturbance made 26 years earlier. On the other hand, the biological activity measured in the track by instruments aboard the crewed submersible

A submersible is an underwater vehicle which needs to be transported and supported by a larger ship, watercraft or dock, platform. This distinguishes submersibles from submarines, which are self-supporting and capable of prolonged independent ope ...

bathyscaphe '' Nautile'' did not differ from a nearby unperturbed site. This data suggests that the benthic fauna and nutrient fluxes at the water–sediment interface has fully recovered.

List of abyssal plains

See also

* List of oceanic landforms * List of submarine topographical features * Oceanic ridge * Physical oceanographyReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Abyssal Plain Coastal and oceanic landforms Submarine topography Oceanic plateaus Oceanographical terminology Physical oceanography Aquatic ecology