1345 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Year 1345 ( MCCCXLV) was a

*

Besides the War of Succession and the Hundred Years' War, France was in the midst of an interesting period. Several decades earlier, the Roman Papacy had moved to Avignon and would not return to Rome for another 33 years. The

Besides the War of Succession and the Hundred Years' War, France was in the midst of an interesting period. Several decades earlier, the Roman Papacy had moved to Avignon and would not return to Rome for another 33 years. The

In 1345, the Greek island of

In 1345, the Greek island of

common year starting on Saturday

A common year starting on Saturday is any non-leap year (i.e. a year with 365 days) that begins on Saturday, 1 January, and ends on Saturday, 31 December. Its dominical letter hence is B. The most recent year of such kind was 2022, and the next ...

of the Julian calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

. It was a year in the 14th century

The 14th century lasted from 1 January 1301 (represented by the Roman numerals MCCCI) to 31 December 1400 (MCD). It is estimated that the century witnessed the death of more than 45 million lives from political and natural disasters in both Euro ...

, in the midst of a period in human history

Human history or world history is the record of humankind from prehistory to the present. Early modern human, Modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago and initially lived as hunter-gatherers. They Early expansions of hominin ...

often referred to as the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

.

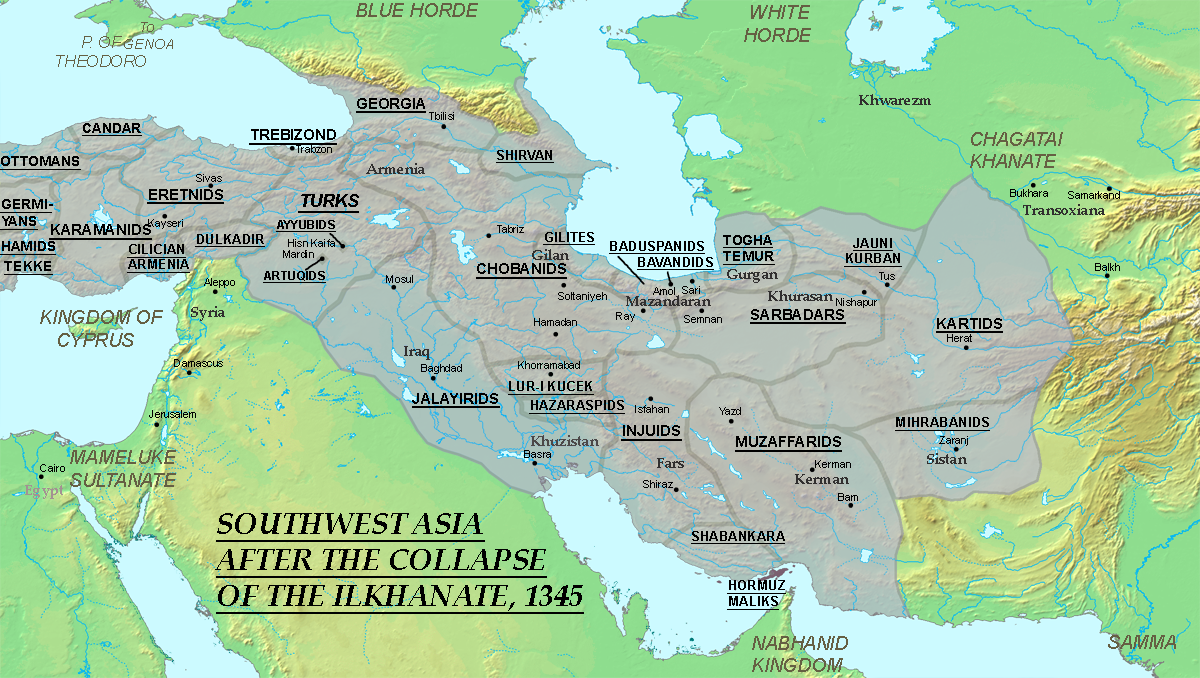

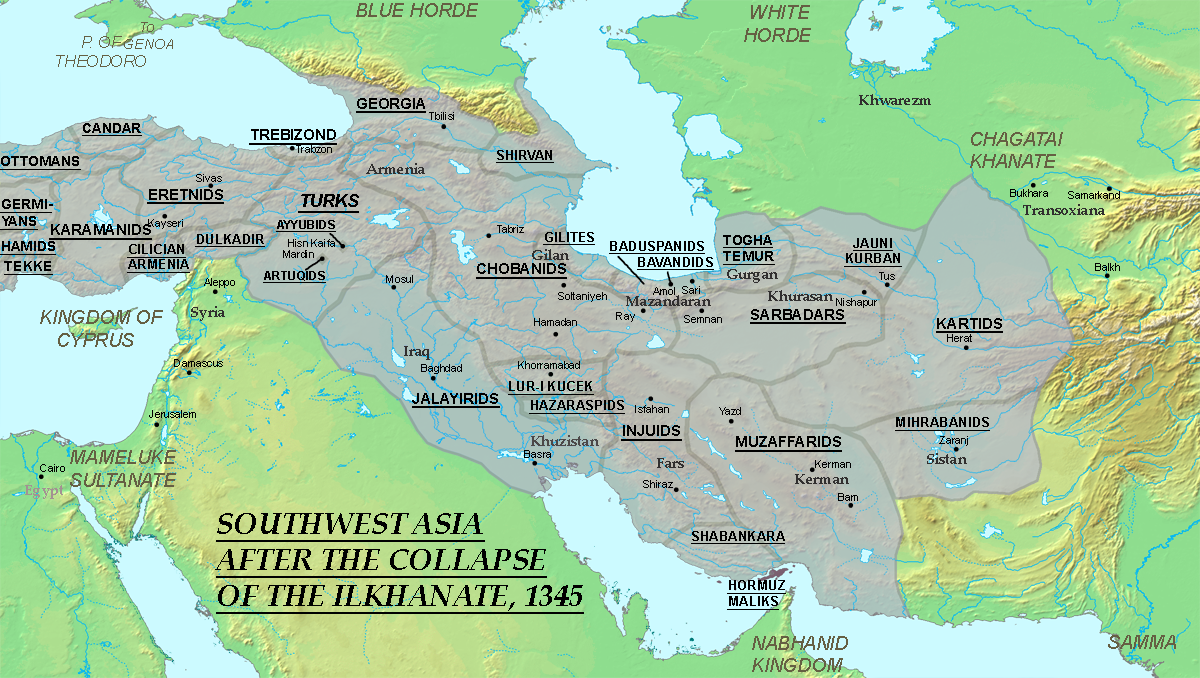

During this year on the Asian continent, several divisions of the old Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

were in a state of gradual decline. The Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate or Il-khanate was a Mongol khanate founded in the southwestern territories of the Mongol Empire. It was ruled by the Il-Khans or Ilkhanids (), and known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (). The Ilkhanid realm was officially known ...

had already fragmented into several kingdoms struggling to place their puppet emperors over the shell of an old state. The Chagatai Khanate was in the midst of a civil war and one year from falling to rebellion. The Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

to the north was besieging Genoese colonies

The Genoese colonies were a series of economic and trade posts in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Black Seas. Some of them had been established directly under the patronage of the republican authorities to support the economy of the loca ...

along the coast of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

, and the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

in China was seeing the first seeds of a resistance which would lead to its downfall. Southeast Asia remained free from Mongol power, with several small kingdoms struggling for survival. The Siamese dynasty in that area vanquished the Sukhothai in this year. In the Indonesian Archipelago, the Majapahit Empire

Majapahit (; (eastern and central dialect) or (western dialect)), also known as Wilwatikta (; ), was a Javanese Hindu-Buddhist thalassocratic empire in Southeast Asia based on the island of Java (in modern-day Indonesia). At its greatest ...

was in the midst of a golden age under the leadership of Gajah Mada, who remains a famous figure in Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

.

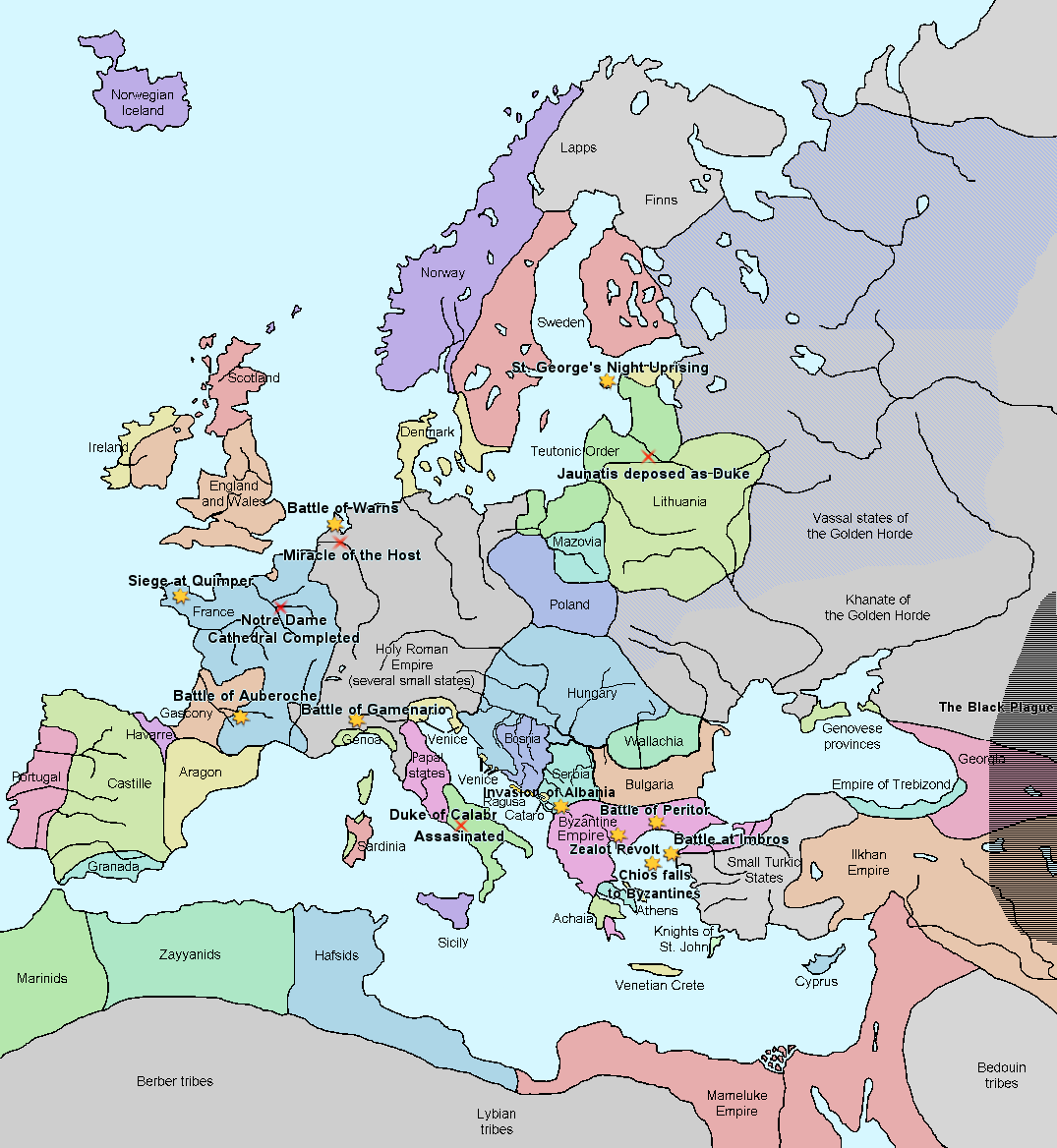

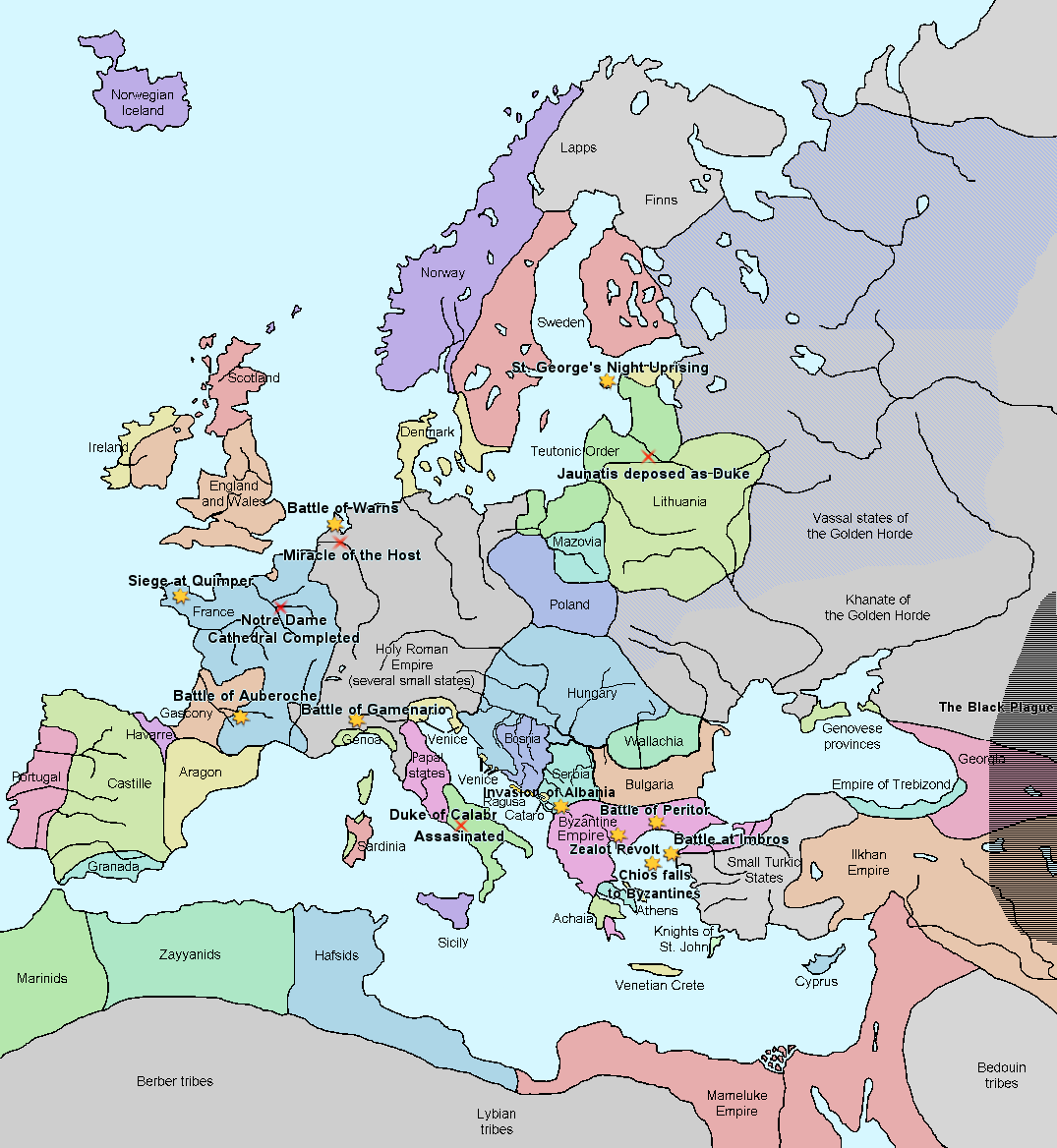

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

were engaged in the early stages of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

, with the Battle of Auberoche fought in Northern France in October of this year. In the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, Alfonso XI of Castile

Alfonso XI (11 August 131126 March 1350), called the Avenger (''el Justiciero''), was King of Castile and León. He was the son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal. Upon his father's death in 1312, several disputes ...

again besieged the Muslim city of Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

as part of the Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

, but without success. The Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

under Louis IV took control of Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

and the surrounding area, granting these lands to his wife Margaret II, Countess of Hainaut in a move which angered many of his princes. Holland was also in the midst of the Friso-Hollandic Wars, engaging with the Frisians

The Frisians () are an ethnic group indigenous to the German Bight, coastal regions of the Netherlands, north-western Germany and southern Denmark. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland an ...

on 26 September in the Battle of Warns. Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, which at the time was divided into several principalities, saw several power struggles including the Battle of Gamenario in the north, and the assassination of Andrew, Duke of Calabria in the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

. In Northern Europe, Swedes

Swedes (), or Swedish people, are an ethnic group native to Sweden, who share a common ancestry, Culture of Sweden, culture, History of Sweden, history, and Swedish language, language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countries, ...

continued early stages of their emigration to Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, which would continue in the coming decades. Estonian rulers also managed to crush the St. George's Night Uprising in 1345 after a two-year struggle. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

changed hands from Jaunutis

Jaunutis (; ; ; Christian name: Ioann; also ''John'' or ''Ivan''; – after 1366) was List of Lithuanian monarchs, Grand Duke of Lithuania after his father Gediminas died in 1341 until he was deposed by his elder brothers Algirdas and Kęstutis ...

to his brother Algirdas

Algirdas (; , ; – May 1377) was List of Lithuanian monarchs, Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1345 to 1377. With the help of his brother Kęstutis (who defended the western border of the Duchy) he created an empire stretching from the pre ...

in a relatively bloodless shift of power, and Lithuania continued its skirmishes with its northern, Estonian neighbor.

The main forces in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

in 1345 were Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. Stefan Uroš IV Dušan of Serbia proclaimed himself Tsar of the new Serbian Empire

The Serbian Empire ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Српско царство, Srpsko carstvo, separator=" / ", ) was a medieval Serbian state that emerged from the Kingdom of Serbia. It was established in 1346 by Dušan the Mighty, who significantly expande ...

and continued his efforts at expansion, quickly conquering Albania and other surrounding areas within the year. The Byzantines, though powerful, were in a state of decline, with an ongoing civil war between emperors John V Palaiologos

John V Palaiologos or Palaeologus (; 18 June 1332 – 16 February 1391) was Byzantine emperor from 1341 to 1391, with interruptions. His long reign was marked by constant civil war, the spread of the Black Death and several military defea ...

and John VI Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene (; ; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under Andronikos III Palaiologos and regent for John V Palaiologos before reigning as Byza ...

, although in 1345, the tide began to turn toward the latter. At the same time, the Zealot commune in Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area) and the capital city, capital of the geographic reg ...

entered a more radical phase.

Turks clashed with Byzantines, Serbs, and Cypriots at sea and in the islands of Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

and Imbros. The Byzantine Empire's precarious situation at this time is evidenced by the fact that they did not have enough soldiers to protect their own borders, but hired mercenaries from the Serbs and the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

.

Events

January 17

Events Pre-1600

* 38 BC – Octavian divorces his wife Scribonia and marries Livia Drusilla, ending the fragile peace between the Second Triumvirate and Sextus Pompey.

* 1362 – Saint Marcellus' flood kills at least 25,000 peopl ...

– The Turks attack Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

.

* March 15

Events Pre-1600

* 474 BC – Roman consul Aulus Manlius Vulso celebrates an ovation for concluding the war against Veii and securing a forty years truce.

* 44 BC – The assassination of Julius Caesar, the dictator of the Roman R ...

– The Miracle of the Host occurs (as commemorated in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

).

* March 4

Events Pre-1600

* AD 51 – Nero, later to become Roman emperor, is given the title '' princeps iuventutis'' (head of the youth).

* 306 – Martyrdom of Saint Adrian of Nicomedia.

* 581 – Yang Jian declares himself Emperor ...

– Guy de Chauliac observes the planets Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars conjoined in the sky, under the sign of Aquarius, and a solar eclipse on the same day. This sign is interpreted as foreboding by many, and Chauliac will later blame it for the Black Plague.pgs. 143–148 ASIN B000K6TDP2Horrox, Rosemary. ''The Black Death''. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994. pg.104–105

* April

April is the fourth month of the year in the Gregorian and Julian calendars. Its length is 30 days.

April is commonly associated with the season of spring in the Northern Hemisphere, and autumn in the Southern Hemisphere, where it is the ...

– Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

offers "defiance" of Philip VI of France

Philip VI (; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (), the Catholic (''le Catholique'') and of Valois (''de Valois''), was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 until his death in 1350. Philip's reign w ...

.

* April 22

Events Pre-1600

* 1500 – Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral lands in Brazil ( discovery of Brazil).

* 1519 – Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés establishes a settlement at Veracruz, Mexico.

* 1529 – Treaty of Zara ...

– Battle of Gamenario: The Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

defeat the Angevins in the northwest region of present-day Italy, just southeast of Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

.

* May

May is the fifth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Its length is 31 days.

May is a month of spring in the Northern Hemisphere, and autumn in the Southern Hemisphere. Therefore, May in the Southern Hemisphere is the ...

– The Turks, led by Umur Beg, sail from Asia Minor to the Balkan Peninsula, and raid Bulgarian territory.Ioannes Cantacuzenus. ''Historiarum...'' 2, p.530

*"Summer" (undated) – Louis IV's son, Louis VI the Roman, marries Cunigunde, a Lithuanian princess.

* July 7 – Battle of Peritheorion: the forces of Momchil, autonomous ruler of the Rhodope, are defeated by the Turkish allies of John VI Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene (; ; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under Andronikos III Palaiologos and regent for John V Palaiologos before reigning as Byza ...

.Nicephorus Gregoras. ''Byzantina historia''. 2, p.729

* August

August is the eighth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Its length is 31 days.

In the Southern Hemisphere, August is the seasonal equivalent of February in the Northern Hemisphere. In the Northern Hemisphere, August ...

– Gascon campaign of 1345

The Gascon campaign of 1345 was conducted by Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster, Henry, Earl of Derby, as part of the Hundred Years' War. The whirlwind campaign took place between August and November 1345 in Gascony, an Kingdom of England, En ...

- Battle of Bergerac

The Battle of Bergerac was fought between Anglo-Gascon and French forces at the town of Bergerac, Dordogne, Bergerac, Gascony, in August 1345 during the Hundred Years' War. In early 1345 Edward III of England decided to launch a major attack o ...

, Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

: English troops are victorious over the French.

* September

September is the ninth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Its length is 30 days.

September in the Northern Hemisphere and March in the Southern Hemisphere are seasonally equivalent.

In the Northern hemisphere, the b ...

– Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

, Hainaut and Zeeland

Zeeland (; ), historically known in English by the Endonym and exonym, exonym Zealand, is the westernmost and least populous province of the Netherlands. The province, located in the southwest of the country, borders North Brabant to the east ...

are inherited by Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Louis IV (; 1 April 1282 – 11 October 1347), called the Bavarian (, ), was King of the Romans from 1314, King of Italy from 1327, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1328 until his death in 1347.

20 October 1314 imperial election, Louis' election a ...

, and remain part of the imperial crown domain until 1347.

* September 18

Events Pre-1600

* 96 – Emperor Domitian is assassinated as a result of a plot by his wife Domitia and two Praetorian prefects. Nerva is then proclaimed as his successor.

* 324 – Constantine the Great decisively defeats Licinius i ...

– Andrew, Duke of Calabria, is assassinated in Naples (d. in Aversa

Aversa () is a city and ''comune'' in the Province of Caserta in Campania, southern Italy, about 24 km north of Naples. It is the centre of an agricultural district, the ''Agro Aversano'', producing wine and cheese (famous for the typical dome ...

).

* September 26 – Battle of Warns: The Frisians

The Frisians () are an ethnic group indigenous to the German Bight, coastal regions of the Netherlands, north-western Germany and southern Denmark. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland an ...

defeat the forces of Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

under William II, Count of Hainaut, in the midst of the Friso-Hollandic Wars.

* October 21 – Battle of Auberoche in Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

: The English defeat the French.

* November 8 – The English take La Réole in Gascony.

* December

December is the twelfth and final month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. Its length is 31 days.

December's name derives from the Latin word ''decem'' (meaning ten) because it was originally the tenth month of the year in t ...

– The English take Aiguillon in Gascony.

Asia

Western Asia

The country ofGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

had been struggling for independence from the Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate or Il-khanate was a Mongol khanate founded in the southwestern territories of the Mongol Empire. It was ruled by the Il-Khans or Ilkhanids (), and known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (). The Ilkhanid realm was officially known ...

since the first anti-Mongol uprising started in 1259 under the leadership of King David Narin who in fact waged his war for almost thirty years. Finally, it was King George the Brilliant (1314–1346) who managed to play on the decline of the Ilkhanate, stopped paying tribute to the Mongols, restored the pre-1220 state borders of Georgia, and returned the Empire of Trebizond into Georgia's sphere of influence. Thus, in 1345, Georgia was in the midst of golden age of independence, though its leader would die one year later.

Trebizond had reached its greatest wealth and influence during the long reign of Alexios II (1297–1330). It was now in a period of repeated imperial depositions and assassinations that lasted from the end of Alexios II's reign until the first years of Alexios III's, finally ending in 1355. The empire never fully recovered its internal cohesion, commercial supremacy or territory. Its ruler in 1345, Michael Megas Komnenos, was crowned Emperor of Trebizond in 1344 after his son, John III, was deposed. He was forced to sign a document which gave the Grand Duke and his ministers almost all power in the Empire, promising to seek their counsel in all official actions. This constitutional experiment was short-lived, however, because of opposition from the people of Trebizond, who rose up in revolt against the oligarchy. Michael swiftly took advantage of his opportunity to regain power and arrested and imprisoned the Grand Duke in 1345. He also sent his son John to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

and then Adrianople

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

, where he was to be kept prisoner to prevent him from becoming a focus of dissent.

Mongol khanates

TheMongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

had become fractured since the late 13th century. After the death of Kublai Khan in 1294, it had already been divided into four khanate

A khanate ( ) or khaganate refers to historic polity, polities ruled by a Khan (title), khan, khagan, khatun, or khanum. Khanates were typically nomadic Mongol and Turkic peoples, Turkic or Tatars, Tatar societies located on the Eurasian Steppe, ...

s: The Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

, the Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate or Il-khanate was a Mongol khanate founded in the southwestern territories of the Mongol Empire. It was ruled by the Il-Khans or Ilkhanids (), and known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (). The Ilkhanid realm was officially known ...

, the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

, and the Chagatai Khanate.

Ilkhanate

TheIlkhanate

The Ilkhanate or Il-khanate was a Mongol khanate founded in the southwestern territories of the Mongol Empire. It was ruled by the Il-Khans or Ilkhanids (), and known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (). The Ilkhanid realm was officially known ...

had been declining rapidly since 1335, when Abu Sa'id died without an heir. Since then, various factions, including the Chobanids and the Jalayirids, had been competing for the Ilkhan throne. Hassan Kuchak, a Chobanid prince, was murdered late in 1343. Surgan, son of Sati Beg, the sister of Abu Sa'id, found himself competing for control of the Chobanid lands with the late ruler's brother Malek Ashraf and his uncle Yagi Basti. When he was defeated by Malek Asraf, he fled to his mother and stepfather. The three of them then formed an alliance, but when Hasan Buzurg (Jalayirid) decided to withdraw the support he promised, the plan fell apart, and they fled to Diyarbakır

Diyarbakır is the largest Kurdish-majority city in Turkey. It is the administrative center of Diyarbakır Province.

Situated around a high plateau by the banks of the Tigris river on which stands the historic Diyarbakır Fortress, it is ...

. Surgan was defeated again in 1345 by Malek Asraf and they fled to Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. Coinage dating from that year appears in Hesn Kayfa in Sati Beg's name; this is the last trace of her. Surgan moved from Anatolia to Baghdad, where he was eventually executed by Hasan Buzurg; Sati Beg may have suffered the same fate, but this is unknown.

Golden Horde

In 1345, theGolden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

made a second attempt to lay siege on the Genoese city of Kaffa. (An earlier attempt had failed because Kaffa was able to get provisions across the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

.) The 1345 siege would fail in the following year as the Mongols were struck with the Black Plague and forced to retreat. This siege is therefore noted as one of the key events that brought the Black Plague to Europe.

The Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

saw the threat of the growing power of the Golden Horde and as such, in 1345 it began a campaign against the Tatars and the Horde, in the area what would become a few years later Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

. Andrew Lackfi, the Voivode

Voivode ( ), also spelled voivod, voievod or voevod and also known as vaivode ( ), voivoda, vojvoda, vaivada or wojewoda, is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe in use since the Early Mid ...

of Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

and his Székely warriors were victorious in their campaign, decapitating the local Tatar leader, the brother-in-law of the Khan, Atlamïş and making the Tatars flee toward the coastal area.

Chagatai Khanate

Amir Qazaghan (d. 1358) was the leader of the Qara'unas tribe (1345 at the latest – 1358) and the powerful de facto ruler of the Chagatai ''ulus'' (1346–1358). In 1345 he revolted against Qazan Khan, but was unsuccessful. The following year he would try again and succeed in killing the khan. With this the effective power of the Chagatai khans would come to an end; the khanate eventually devolved into a loose confederation of tribes that respected the authority of Qazaghan, although he primarily commanded the loyalty of the tribes of the southern portion of the ''ulus''. He did not claim the khanship, but instead contented himself with his title ofamir

Emir (; ' (), also transliterated as amir, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or ceremonial authority. The title has ...

and conferred the title of khan on puppets of his own choosing: first Danishmendji (1346–1348) and then Bayan Qulï (1348–1358).

Yuan dynasty

By 1345, theYuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

in China was steadily declining. Chinese peasants, upset with the lack of effective policies by the government when they were facing droughts, floods, and famines, were becoming rebellious. The Yellow River

The Yellow River, also known as Huanghe, is the second-longest river in China and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system on Earth, with an estimated length of and a Drainage basin, watershed of . Beginning in the Bayan H ...

flooded in Jinan

Jinan is the capital of the province of Shandong in East China. With a population of 9.2 million, it is one of the largest cities in Shandong in terms of population. The area of present-day Jinan has played an important role in the history of ...

in 1345. The river had flooded previously in 1335 and in 1344. There was also conflict between the rulers of the dynasty. Zhu Yuanzhang was about 16 years old in 1345. His parents and brothers had died of plague or famine (or both) in 1344, Huang, Ray. 1988. ''China: A Macro History''. Armonk, New York; London: M. E. Sharpe, Inc. . 149. and he joined a Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

monastery. In 1345 he left the monastery and joined a band of rebels. He would lead a series of rebellions until he overthrew the Yuan dynasty and became the first emperor of the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

in 1368.

Japan and India

Muhammad bin Tughluq was reigning as Sultan of Delhi in 1345 when there was a revolt of Muslim military commanders in the Daulatabad area. In Bengal, on the eastern border of the Sultanate, a general named llyas captured East Bengal, leading to its reunification. He established his capital at Gaur. In southern India, Harihara I had founded theVijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire, also known as the Karnata Kingdom, was a late medieval Hinduism, Hindu empire that ruled much of southern India. It was established in 1336 by the brothers Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of the Sangama dynasty, belongi ...

in 1336. After the death of Hoysala Veera Ballala III

Veera Ballala III ( – 8 September 1342) was the last great king of the Hoysala Empire. During his rule, the northern and southern branches of the Hoysala empire (which included much of modern Karnataka and northern Tamil Nadu in India) w ...

during a battle against the Sultan of Madurai in 1343, the Hoysala Empire had merged with the growing Vijayanagara Empire. In these first two decades after the founding of the empire, Harihara I gained control over most of the area south of the Tungabhadra river and earned the title of ''Purvapaschima Samudradhishavara'' ("master of the eastern and western oceans"). The Jaffna Kingdom

The Jaffna kingdom (, ; 1215–1619 CE), also known as Kingdom of Aryachakravarti, was a historical kingdom of what today is northern Sri Lanka. It came into existence around the town of Jaffna on the Jaffna peninsula and was traditionally t ...

, which encompassed the southern tip of India and parts of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

; there was continual conflict with Vijayanagara and the smaller Kotte Kingdom of southern Sri Lanka.

From 1336 to 1392, two courts claimed the throne of Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. This was known as the Nanboku-chō, or the Northern and Southern Courts period. In the Northern Court

The , also known as the Ashikaga Pretenders or Northern Pretenders, were a set of six pretenders to the throne of Japan during the Nanboku-chō period from 1336 through 1392. Even though the present Imperial House of Japan is descended from the ...

, Emperor Go-Murakami claimed the throne. In the Southern Court, Emperor Kōmyō claimed the throne.

Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, Sukhothai changed hands to a new Siamese dynasty in 1345. A Buddhist work, the ''Traibhumikatha'', was composed by the King of Siam in the same year. The Sukhothai Emperor also wrote a similar Buddhist work, the ''Tri Phum Phra Ruang''. Both works describe Southeast Asian cosmological ideas which still exist today. Life is said in these books to be divided into 31 levels of existence separated between three worlds.Angkor

Angkor ( , 'capital city'), also known as Yasodharapura (; ),Headly, Robert K.; Chhor, Kylin; Lim, Lam Kheng; Kheang, Lim Hak; Chun, Chen. 1977. ''Cambodian-English Dictionary''. Bureau of Special Research in Modern Languages. The Catholic Uni ...

was in a period of decline, forced to devote much of its resources to skirmishes with the Sukhothai and Siamese, which left Champa

Champa (Cham language, Cham: ꨌꩌꨛꨩ, چمڤا; ; 占城 or 占婆) was a collection of independent Chams, Cham Polity, polities that extended across the coast of what is present-day Central Vietnam, central and southern Vietnam from ...

free to attack Đại Việt and opened the way for Lopburi to spring up, all of which happened right around this year. A Buddhist colony also existed to the west in the Mon Empire, which struggled to maintain its existence in the face of the Islamic Delhi Sultanate to the west and the Mongol Chinese to the north.

The Majapahit Empire, which occupied much of the Indonesian Archipelago, was ruled by empress Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi. During Tribhuwana's rule, the Majapahit kingdom had grown much larger and became famous in the area. Gajah Mada reigned at the time along with the empress as ''mahapatih'' (prime minister) of Majapahit

Majapahit (; (eastern and central dialect) or (western dialect)), also known as Wilwatikta (; ), was a Javanese people, Javanese Hinduism, Hindu-Buddhism, Buddhist thalassocracy, thalassocratic empire in Southeast Asia based on the island o ...

. It was during their rule in 1345 that the famous Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta

Ibn Battuta (; 24 February 13041368/1369), was a Maghrebi traveller, explorer and scholar. Over a period of 30 years from 1325 to 1354, he visited much of Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Iberian Peninsula. Near the end of his life, Ibn ...

visited Samudra in the Indonesian Archipelago. According to Battuta's report on his visit to Samudra, the ruler of the local area was a Muslim, and the people worshiped as Muslims in mosques and recited the Koran. Many Islamic traders and travelers had already scattered themselves along the major cities and coasts surrounding the Indian Ocean by this time.

Western Europe

Hundred Years' War

By 1345, theHundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

between France and England had been going on for only about eight years. The English claimed the right to the French throne, and the French refused to be ruled by foreigners. In August the English Earl of Derby commenced the Gascon campaign of 1345

The Gascon campaign of 1345 was conducted by Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster, Henry, Earl of Derby, as part of the Hundred Years' War. The whirlwind campaign took place between August and November 1345 in Gascony, an Kingdom of England, En ...

, taking a large French army at Bergerac, Dordogne by surprise and decisively defeating it. Later in the campaign, on 21 October the French were besieging the castle at Auberoche, when Derby's army caught them off guard during their evening meal and won one of the most decisive battles of the war. This set the stage for English dominance in the area for several years. Previous to this, the French had been having success, and the English had even offered a treaty, but with this battle along with Derby's overrunning of the Agenais (lost twenty years before in the War of Saint-Sardos) and Angoulême

Angoulême (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Engoulaeme''; ) is a small city in the southwestern French Departments of France, department of Charente, of which it is the Prefectures of France, prefecture.

Located on a plateau overlooking a meander of ...

, as well as the forces in Brittany under Sir Thomas Dagworth also making gains, the tide turned somewhat in this year.

A new machine was introduced to this war in 1345—cannon. "Ribaldis", as they were then called, are first mentioned in the English Privy Wardrobe accounts during preparations for the Battle of Crécy between 1345 and 1346.David Nicolle

David C. Nicolle (born 4 April 1944) is a British historian specialising in the military history of the Middle Ages, with a particular interest in the Middle East. Life

David Nicolle worked for BBC Arabic before getting his MA at SOAS, Univers ...

, ''Crécy 1346: Triumph of the longbow'', Osprey Publishing. Paperback; June 25, 2000; These were believed to have shot large arrows and simplistic grapeshot, but they were so important they were directly controlled by the Royal Wardrobe.

War of Succession

A kind of side conflict to the Hundred Years' War was theWar of the Breton Succession

The War of the Breton Succession (, ) or Breton Civil War was a conflict between the Counts of Blois and the Montfort of Brittany, Montforts of Brittany for control of the Duchy of Brittany, then a fief of the Kingdom of France. It was fou ...

, a conflict between the Houses of Blois and Montfort for control of the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany (, ; ) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of France, bordered by the Bay of Biscay to the west, and the English Channel to the north. ...

. The French backed Blois and the English backed Montfort in what became a miniature of the wider conflict between the two countries. The House of Blois had laid siege to the town of Quimper

Quimper (, ; ; or ) is a Communes of France, commune and Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Finistère Departments of France, department of Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in northwestern France.

Administration

Quimper is the ...

in early 1344, and continued into 1345. During the summer and autumn of 1344, the Montfortist party had fallen apart. Even those who had been John of Montfort's staunchest allies now considered it futile to continue the struggle. It therefore mattered little that in March 1345 John finally managed to escape to England. With no adherents of note of his own, he was now little more than a figurehead for English ambitions in Brittany.

Edward III decided to repudiate the truce in summer 1345, a year before it was due to run out. As part of his larger strategy, a force was dispatched to Brittany under the joint leadership of the Earl of Northampton and John of Montfort. Within a week of their landing in June, the English had their first victory when Sir Thomas Dagworth, one of Northampton's lieutenants, raided central Brittany and defeated Charles of Blois at Cadoret near Josselin.

The follow-up was less impressive. Further operations were delayed until July when Montfort attempted the recapture of Quimper. However, news had reached the French government that Edward's main campaign had been cancelled and they were able to send reinforcements from Normandy. With his strengthened army, Charles of Blois broke the siege. Routed, Montfort fled back to Hennebont where he fell ill and died 16 September. The heir to the Montfortist cause was his 5-year-old son, John.

During the winter, Northampton fought a long and hard winter campaign with the apparent objective of seizing a harbour on the north side of the peninsula. Edward III had probably planned to land here with his main force during summer 1346. However, the English achieved very little for their efforts. Northern Brittany was Joanna of Dreux’ home region and resistance here was stiff. The only bright spot for the English was victory at the Battle of La Roche-Derrien, where the small town was captured and a garrison installed under Richard Totesham.

Other events

Also in England in 1345, Princess Joan was betrothed toPedro of Castile

Peter (; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called Peter the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and List of Leonese monarchs, León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated ...

, son of Alfonso XI of Castile

Alfonso XI (11 August 131126 March 1350), called the Avenger (''el Justiciero''), was King of Castile and León. He was the son of Ferdinand IV of Castile and his wife Constance of Portugal. Upon his father's death in 1312, several disputes ...

and Maria of Portugal. She would never marry him, however, but would die of the Black Plague on her journey to Spain to meet him. Spain, meanwhile, continued its struggle to regain Muslim territory on the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

. In that same year Alfonso XI attacked Gibraltar as a part of the Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

, but was unable to conquer it. In 1345 Muhammud V was made its ruler. The York Minster Cathedral, the largest Gothic cathedral in northern Europe, was completed in this year as well. It remains the largest in the region to this day. England was still recovering from French occupation. Until 1345, all school instruction had been in French, rather than English.

Besides the War of Succession and the Hundred Years' War, France was in the midst of an interesting period. Several decades earlier, the Roman Papacy had moved to Avignon and would not return to Rome for another 33 years. The

Besides the War of Succession and the Hundred Years' War, France was in the midst of an interesting period. Several decades earlier, the Roman Papacy had moved to Avignon and would not return to Rome for another 33 years. The Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy (; ) was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon (at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire, now part of France) rather than in Rome (now the capital of ...

was then ruled by Pope Clement VI, who was aiding the French in their war against the English with Church funds. Also, in the year 1345, the famous Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. It ...

in Paris was completed after nearly two centuries of planning and construction. On 24 March, a man named Guy de Chauliac observed a strange astronomical sign: the planets Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars conjoined in the sky under the sign of Aquarius. That same day the area experienced a solar eclipse. This sign was interpreted as foreboding by many, and Chauliac would later blame it for the Black Plague, which arrived less than five years later.

Central Europe

Holy Roman Empire

On 1 January, emperor Louis IV's son Louis VI the Roman married Cunigunde, a Lithuanian Princess. Besides this move, the emperor continued his policy of expansion by conferring Hainaut,Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

, Zeeland

Zeeland (; ), historically known in English by the Endonym and exonym, exonym Zealand, is the westernmost and least populous province of the Netherlands. The province, located in the southwest of the country, borders North Brabant to the east ...

and Friesland

Friesland ( ; ; official ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia (), named after the Frisians, is a Provinces of the Netherlands, province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen (p ...

upon his wife Margaret of Holland after the death of William IV at the Battle of Warns. The hereditary titles to these lands owned by Margaret's sisters were ignored. This widened a divide which had already been growing between himself and the lay princes of Germany, who disliked his restless expansion policy. His actions in this year eventually led to a civil war, which was cut short by his death by stroke two years later.

On 12 March, a eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

ic miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

occurred in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

, now called the Miracle of the Host. It involved a dying man vomiting upon being given the Holy Sacrament and last rites in his home. The Host was then put in the fire, but miraculously remained intact and could be retrieved from the fire in one piece without the heat burning the hand of the person that retrieved it. This miracle was later officially recognised as such by the Roman Catholic Church, and a large pilgrimage chapel was built where the house had stood. Every year, thousands of Catholics take part in the Stille Omgang, or procession to the place of the miracle.

Holland, meanwhile, was in the midst of the Friso-Hollandic Wars, as the Counts of Holland continued their efforts to conquer nearby Friesland

Friesland ( ; ; official ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia (), named after the Frisians, is a Provinces of the Netherlands, province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen (p ...

in the Battle of Warns. In 1345 William IV, Count of Holland, prepared a military action to conquer Middle Frisia, crossing the Zuiderzee with a large fleet and with the help of French and Flemish knights, some of whom had just returned from crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. He set sail in Enkhuizen, together with his uncle John of Beaumont, and landed near Stavoren and Laaxum and planned to use the Sint-Odulphus monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

near Stavoren as a fortification

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lati ...

. The Hollandic knights wore armour

Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, e ...

, but had no horses as there wasn't enough room in the ships, which were full of building materials and supplies.

William's troops set fire to the abandoned villages of Laaxum and Warns and started to advance towards Stavoren. In the countryside around Warns the Hollandic count was attacked by the local inhabitants. With their heavy armour the knights were no match for the furious Frisian farmers and fishermen. As they fled they entered a swamp where they were decisively beaten. Their commander William IV of Holland was killed, and was succeeded by his sister Margaret of Holland, wife of Louis IV. When John of Beaumont heard what had happened, he ordered a retreat back to the ships. They were pursued by the Frisians and most did not make it back. Count William's death in this battle paved the way for the Hook and Cod wars, and 26 September, the day of the battle, remains a national holiday in Friesland

Friesland ( ; ; official ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia (), named after the Frisians, is a Provinces of the Netherlands, province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen (p ...

today.

Italy

The Battle of Gamenario, fought on 22 April, was a decisive battle of the wars between the Guelfs ( Angevins) and Ghibellines (Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

). It took place in northwest Italy in what is now part of the commune of Santena about 15 km southeast of Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

.

Reforza d'Agoult was sent in the spring of 1345 by Joanna of Anjou, viceroy to northern Italy in hopes of putting an end to the war with the Margravate of Montferrat. Reforza conquered Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English-language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingd ...

and besieged Gamenario, a castle in the neighbourhood of Santena. Lombard Ghibellines formed an anti-Angevin alliance, headed by John II, Marquess of Montferrat. On 22 April, he confronted Reforza d'Agoult and battle was joined. The meeting was brief and bloody. Initially uncertain, the outcome was a victory for the Ghibellines, who recovered the besieged fortress and dealt a severe blow to Angevin influence in Piedmont. To celebrate his victory, John built a new church in Asti

Asti ( , ; ; ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) of 74,348 inhabitants (1–1–2021) located in the Italy, Italian region of Piedmont, about east of Turin, in the plain of the Tanaro, Tanaro River. It is the capital of the province of Asti and ...

in honour of Saint George

Saint George (;Geʽez: ጊዮርጊስ, , ka, გიორგი, , , died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was an early Christian martyr who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to holy tradition, he was a soldier in the ...

, near whose feast day the battle was won. Saint George held a special place for the men of chivalry of the Medieval, because he was the Saint that killed the dragon and was therefore held in a warrior cult.

In the aftermath, Piedmont was partitioned between the victors. John received Alba, Acqui Terme, Ivrea, and Valenza. Luchino Visconti

Luchino Visconti di Modrone, Count of Lonate Pozzolo (; 2 November 1906 – 17 March 1976) was an Italian filmmaker, theatre and opera director, and screenwriter. He was one of the fathers of Italian neorealism, cinematic neorealism, but later ...

received Alessandria and the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

(related to the Palaiologos

The House of Palaiologos ( Palaiologoi; , ; female version Palaiologina; ), also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was a Byzantine Greeks, Byzantine Greek Nobility, noble family that rose to power and produced th ...

of Montferrat

Montferrat ( , ; ; , ; ) is a historical region of Piedmont, in northern Italy. It comprises roughly (and its extent has varied over time) the modern provinces of Province of Alessandria, Alessandria and Province of Asti, Asti. Montferrat ...

) received Chieri. The Angevins lost almost complete control of the region and many formerly French cities declared themselves independent. The defeat of the Angevins was also a defeat for Angevin-supported Manfred V, Marquess of Saluzzo and the civil war in that margraviate was ended at Gamenario.

Andrew, Duke of Calabria, was assassinated by conspiracy in 1345. He had been appointed joint heir with his wife, Joan I, to the throne of Naples by the Pope. This, however, sat ill with the Neapolitan people and nobles; neither was Joan content to share her sovereignty. With the approval of Pope Clement VI, Joan was crowned as sole monarch of Naples in August 1344. Fearing for his life, Andrew wrote to his mother Elizabeth that he would soon flee the kingdom. She intervened, and made a state visit; before she returned to Hungary, she bribed Pope Clement to reverse himself and permit the coronation of Andrew. She also gave a ring to Andrew, which was supposed to protect him from death by blade or poison, and returned with a false sense of security to Hungary.

Thus, in 1345, hearing of the Pope's reversal, a group of noble conspirators (probably including Queen Joan) determined to forestall Andrew's coronation. During a hunting trip at Aversa, Andrew left his room in the middle of the night and was set upon by the conspirators. A treacherous servant barred the door behind him; and as Joan cowered in their bed, a terrible struggle ensued, Andrew defending himself furiously and shrieking for aid. He was finally overpowered, strangled with a cord, and flung from a window. The horrible deed would taint the rest of Joan's reign.

Other events in Italy in 1345 include Ambrogio Lorenzetti

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (; – after 9 August 1348) was an Italian painter of the Sienese school. He was active from approximately 1317 to 1348. He painted ''The Allegory of Good and Bad Government'' in the Sala dei Nove (Salon of Nine or Council Ro ...

's painting of a map of the world for the palace at Siena

Siena ( , ; traditionally spelled Sienna in English; ) is a city in Tuscany, in central Italy, and the capital of the province of Siena. It is the twelfth most populated city in the region by number of inhabitants, with a population of 52,991 ...

. The painting has since been lost, but the instruments which he used to make it still survive, giving insights into mapmaking techniques of the day. The Peruzzi

The Peruzzi family were bankers of Florence, among the leading families of the city in the 14th century, before the rise to prominence of the Medici. Their modest antecedents stretched back to the mid 11th century, according to the family's gen ...

family, a big banking family and precursor to the Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

family went bankrupt in 1345, and in 1345 Florence was the scene of an attempted strike by wool combers (''ciompi''). A few decades later they would rise in a full-scale revolt. In Verona, Mastino II della Scala began the construction of his Scaliger Tomb, an architectural structure still standing today.

Sweden and Lithuania

In Sweden and states bordering theBaltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

, the oldest surviving manuscript from the first Swedish law to be put to paper is from c. 1345, although earlier versions probably existed. The law was created for the young town Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

's customs

Customs is an authority or Government agency, agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling International trade, the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out ...

, but it was also used in Lödöse and probably in a few other towns, as well. No town was allowed to use the law without the formal permission by the Swedish king. Its use may have become more widespread if it had not been superseded by the new town law by King Magnus Eriksson

Magnus Eriksson (April or May 1316 – 1 December 1374) was King of Sweden from 1319 to 1364, King of Norway as Magnus VII from 1319 to 1355, and ruler of Scania from 1332 to 1360. By adversaries he has been called ''Magnus Smek'' ().

Medi ...

(1316–1374). The term ''Bjarkey Laws'' was however used for a long time for Magnus Eriksson's law in various locations.

Records also exist for the emigration of Swedes to Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

in this year. Early mentions of Swedes in Estonia came in 1341 and 1345 (when an Estonian monastery in Padise sold "the Laoküla Estate" and Suur-Pakri Island to a group of Swedes).

During the 13th through 15th centuries, large numbers of Swedes arrived in coastal Estonia from Finland, which was under Swedish control (and would remain so for hundreds of years), often settling on Church-owned land.

1345 marked the end of a series of skirmishes begun in the 1343 St. George's Night Uprising. The rebellion, which was by this time limited to the island of Saaremaa, was stifled in 1345. After the rebellion Denmark sold its domains in Estonia to the Teutonic Order

The Teutonic Order is a religious order (Catholic), Catholic religious institution founded as a military order (religious society), military society in Acre, Israel, Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Sa ...

in 1346. The fighting had started as a protest by indigenous Estonians to Danish and German rule. Parts of Estonia such as the city of Valga suffered raids from the nearby Lithuanian rulers.

In Lithuania in 1345 Grand Duke

Grand duke (feminine: grand duchess) is a European hereditary title, used either by certain monarchs or by members of certain monarchs' families. The title is used in some current and former independent monarchies in Europe, particularly:

* in ...

Jaunutis

Jaunutis (; ; ; Christian name: Ioann; also ''John'' or ''Ivan''; – after 1366) was List of Lithuanian monarchs, Grand Duke of Lithuania after his father Gediminas died in 1341 until he was deposed by his elder brothers Algirdas and Kęstutis ...

was deposed by his brothers. Very little is known about years when Jaunutis ruled except that they were quite peaceful years, as the Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem was formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to t ...

were led by ineffective Ludolf König. The Bychowiec Chronicle mentions that Jaunutis was supported by Jewna, presumed wife of Gediminas and mother of his children. She died ca. 1344 and soon after Jaunutis lost his throne. If he was indeed protected by his mother, then it would be an interesting example of influence held by queen mother

A queen mother is a former queen, often a queen dowager, who is the mother of the monarch, reigning monarch. The term has been used in English since the early 1560s. It arises in hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarchies in Europe and is also ...

in pagan Lithuania. However, a concrete stimulus might have been a major ''reise'' planned by the Teutonic Knights in 1345.

Balkans

In 1345, the Byzantine civil war continued. Having exploited the conflict to expand his realm into Macedonia, following the conquest ofSerres

Serres ( ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and second largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of Northern Greece. The c ...

Stefan Uroš IV Dušan of Serbia proclaimed himself "Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

of the Serbs and Romans". By the end of the year, his Serbian Empire

The Serbian Empire ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Српско царство, Srpsko carstvo, separator=" / ", ) was a medieval Serbian state that emerged from the Kingdom of Serbia. It was established in 1346 by Dušan the Mighty, who significantly expande ...

included all of Macedonia, except for Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area) and the capital city, capital of the geographic reg ...

, and all of Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, except for Dyrrhachium, held by the Angevins. The first known line of Serbian text written in the Latin alphabet is dated to this year. Serbia was recognized as the most powerful empire in the Balkans for the next several years.

The Byzantine civil war also allowed the emergence of a local quasi-independent principality in the Rhodope, headed by the Bulgarian brigand Momchil, who had switched his allegiance from John VI Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene (; ; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under Andronikos III Palaiologos and regent for John V Palaiologos before reigning as Byza ...

to the regency in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. On 7 July, the army of Umur Beg, the Turkish Emirate of Aydin, emir of Aydin and Kantakouzenos' chief ally, Battle of Peritheorion, met and defeated Momchil's forces at Peritheorion. Momchil himself was killed in the battle.

On 11 June, Alexios Apokaukos, the driving force behind the Constantinopolitan regency and main instigator of the civil war, was murdered. His demise led to a wave of defections to the Kantakouzenist camp, most prominently his own son, John Apokaukos, the governor of Thessalonica. He plotted to surrender the city to Kantakouzenos, and had the leader of the Zealots, a certain Michael Palaiologos, killed. The Zealots however reacted violently: in a popular uprising, led by Andreas Palaiologos, they overpowered Apokaukos and killed or expelled most of the city's remaining aristocrats. The events are described by Demetrius Cydones:

...one after another the prisoners were hurled from the walls of the citadel and hacked to pieces by the mob of the Zealots assembled below. Then followed a hunt for all the members of the upper classes: they were driven through the streets like slaves, with ropes round their necks-here a servant dragged his master, there a slave his purchaser, while the peasant struck the strategus and the labourer beat the soldier (i.e. the pronoiar).

Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

fell to the Genoese Giustiniani. The Genoese also sacked the city of Dvigrad in Istria in this same year. Aquileian patriarchs had for some time fought fiercely against Venetians which had already gained considerable influence on the west coast of Istria. It was during these confrontations that the town fell.

Anatolian Peninsula

In 1344, Hugh IV of Cyprus joined a league with Republic of Venice, Venice and the Knights Hospitaller which burnt a Turkish fleet inSmyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

and captured the city. In 1345 the allies defeated the Turks at Imbros by land and sea, but Hugh could see little benefit for his kingdom in these endeavors and withdrew from the league. Meanwhile, Umur Beg transformed the Beylik of Aydınoğlu into a serious naval power with base in İzmir and posed a threat particularly for Venetian possessions in the Aegean Sea. The Venetians organized an alliance uniting several European parties (''Sancta Unio''), composed notably of the Knights Hospitaller, which organized five consecutive attacks on İzmir and the Western Anatolian coastline controlled by Turkish states. In between, it was the Turks who organized maritime raids directed at Aegean islands.

John XIV sparked the civil conflict when he convinced the Empress that John V's rule was threatened by the ambitions of Kantakouzenos. In September 1341, whilst Kantakouzenos was in Thrace, Kalekas declared himself as regent and launched a vicious attack on Kantakouzenos, his supporters & family. In October Anna ordered Kantakouzenos to resign his command. Kantakouzenos not only refused, he declared himself Emperor at Didymoteichon, allegedly to protect John V's rule from Kalekas. Whether or not Kantakouzenos wished to be Emperor is not known, but the provocative actions of the Patriarch forced Kantakouzenos to fight to retain his power and start the civil war.

There were not nearly enough troops to defend Byzantium's borders at the time and there certainly was not enough for the two factions to split – consequently, more foreigners would flood the Empire into a state of chaos – Kantakouzenos hired Turks and Serbs – his main supply of Turkish mercenaries came from the Umur of Aydin, a nominal ally established by Andronikos III. The Regency of John V relied on Turkish mercenaries as well. However, Kantakouzenos began to draw support from the Ottoman Sultan Orkhan, who wed Kantakouzenos' daughter in 1345. By 1347, Kantakouzenos had triumphed and entered Constantinople. However, in his hour of victory, he came to an accord with Anna and her son, John V. John V (now 15 years of age) and Kantakouzenos would rule as co-emperors, though John V would be the junior in this relationship. The unlikely peace would not last long.

The Turks attacked Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

on January 17 and the Ottomans annexed Qarasi in west Asia minor. Later, Pope Clement urged further attacks on the Levant.

Africa

Pope Clement VI said in 1345: "the acquisition of the kingdom of Africa belongs to us and our royal right and to no one else." Ironically, in the same year, trade was established between Italy and the Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo), Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt. This marked the beginning of reliable trading of spice to the Adriatic Sea.Births

* January 8 – Kadi Burhan al-Din, poet, qadi, kadi, and ruler of Sivas (d. 1398) * March 25 or 1347 – Blanche of Lancaster, wife of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (d. 1369) * October 31 – King Fernando I of Portugal (d. 1383) * December 7 – Thado Minbya, founder of the Kingdom of Ava, Ava kingdom (d. 1367) * ''date unknown'' ** King Charles III of Naples, reign 1381–1386 (d. 1386) ** Eleanor Maltravers, English noblewoman (d. 1405) ** Saint John of Nepomuk, John Wolflin (d. 1393) ** Queen Helen of Bosnia (d. 1399)Deaths

*January 17

Events Pre-1600

* 38 BC – Octavian divorces his wife Scribonia and marries Livia Drusilla, ending the fragile peace between the Second Triumvirate and Sextus Pompey.

* 1362 – Saint Marcellus' flood kills at least 25,000 peopl ...

** Martino Zaccaria, former Genoese Lord of Chios (killed by Turks at Smyrna)

** Henry of Asti, titular Latin Patriarch of Constantinople (killed by Turks at Smyrna)

* September 18

Events Pre-1600

* 96 – Emperor Domitian is assassinated as a result of a plot by his wife Domitia and two Praetorian prefects. Nerva is then proclaimed as his successor.

* 324 – Constantine the Great decisively defeats Licinius i ...

– Andrew, Duke of Calabria (b. 1327)

* September 22 – Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, English politician (b. 1281)

* April 14 – Richard Aungerville (also known as Richard De Bury), English writer and bishop (b. 1287)

* June 11 – Alexios Apokaukos, chief minister of the Byzantine Empire (lynched by political prisoners)

* July 7 – Momchil, semi-independent brigand ruler in the Rhodope Mountains (killed in battle)

* July 24 – Jacob van Artevelde, Flemish statesman (b. 1290) (killed by mob)

* July 28 – Sancia of Majorca, queen regent of Naples (b. c. 1285)

* September 26 – William II, Count of Hainaut (killed in the Battle of Warns)

* November 13 – Constance of Peñafiel, queen of Pedro I of Portugal (b. 1323)

* ''date unknown''

** Aedh mac Tairdelbach Ó Conchobair, King of Connacht

** John Vatatzes (megas stratopedarches), John Vatatzes, Byzantine general (murdered)

** John Apokaukos (died 1345), John Apokaukos, governor of Thessalonica (executed)

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:1345 1345,