ﻕﺕ۴erem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Herem'' ( ''ﻕﺕ۴ﺥrem'') is the highest ecclesiastical censure in the

''Herem'' ( ''ﻕﺕ۴ﺥrem'') is the highest ecclesiastical censure in the

''Herem'' ( ''ﻕﺕ۴ﺥrem'') is the highest ecclesiastical censure in the

''Herem'' ( ''ﻕﺕ۴ﺥrem'') is the highest ecclesiastical censure in the Jewish community

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

. It is the total exclusion of a person from the Jewish community. It is a form of shunning

Shunning can be the act of social rejection, or emotional distance. In a religious context, shunning is a formal decision by a denomination or a congregation to cease interaction with an individual or a group, and follows a particular set of rule ...

and is similar to ''vitandus'' "excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

" in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Cognate terms in other Semitic languages include the Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

terms ''ﻕﺕ۴arﺥm

''Haram'' (; ) is an Arabic term meaning 'taboo'. This may refer to either something sacred to which access is not allowed to the people who are not in a state of purity or who are not initiated into the sacred knowledge; or, in direct cont ...

'' "forbidden, taboo, off-limits, or immoral" and haram "set apart, sanctuary", and the Geﮌﺛez

Geez ( or ; , and sometimes referred to in scholarly literature as Classical Ethiopic) is an ancient South Semitic language. The language originates from what is now Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Today, Geez is used as the main liturgical langu ...

word ''ﮌﺟirm'' "accursed".

Summary

Although developed from thebiblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

ban, excommunication, as employed by the rabbis during Talmudic times and during the Middle Ages, became a rabbinic institution, the object of which was to preserve Jewish solidarity. A system of laws was gradually developed by rabbis, by means of which this power was limited, so that it became one of the modes of legal punishment by rabbinic courts. While it did not entirely lose its arbitrary character, since individuals were allowed to pronounce the ban of excommunication on particular occasions, it became chiefly a legal measure resorted to by a judicial court for certain prescribed offenses.

Etymology and cognate terms

The three terms ''herem'', "censure, excommunication", " devotion of enemies by annihilation" in theTanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. ''

. ''

devotion of property to a

Jewish Encyclopedia 1901: Anathema

Jewish Encyclopedia 1901: Ban

* {{Cite web , url=http://www.roylaw.co.za/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.article&pageID=6218762&ArticleID=7315629 , title=South African High Court upholds Jewish right to pronounce herem , archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130314011604/http://www.roylaw.co.za/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.article&pageID=6218762&ArticleID=7315629 , archive-date=March 14, 2013 Excommunication Jewish courts and civil law Punishments in religion Shunning

kohen

Kohen (, ; , ﻊ Arabic ﻋﻊ۶ﻋﻋ , Kahen) is the Hebrew word for "priest", used in reference to the Aaronic Priest#Judaism, priesthood, also called Aaronites or Aaronides. They are traditionally believed, and halakha, halakhically required, to ...

", are all English transliteration

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another that involves swapping letters (thus '' trans-'' + '' liter-'') in predictable ways, such as Greek ﻗ and ﻗ the digraph , Cyrillic ﻗ , Armenian ﻗ or L ...

s of the same Hebrew noun. This noun comes from the semitic root

The roots of verbs and most nouns in the Semitic languages are characterized as a sequence of consonants or " radicals" (hence the term consonantal root). Such abstract consonantal roots are used in the formation of actual words by adding the vowel ...

ﻕﺕ۳-R-M

''ﻊ, ﻕﺕ۳-ﻊﺎ, R-ﻋ

, M'' (Modern Hebrew, Modern ; ) is the Semitic root, triconsonantal root of many Semitic languages, Semitic words, and many of those words are used as names. The basic meaning expressed by the root translates as "forbidden".

Ara ...

. There is also a homonym

In linguistics, homonyms are words which are either; '' homographs''ﻗwords that mean different things, but have the same spelling (regardless of pronunciation), or '' homophones''ﻗwords that mean different things, but have the same pronunciat ...

''herem'' "fisherman's net", which appears nine times in the Masoretic Text

The Masoretic Text (MT or ﻭﺕ; ) is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (''Tanakh'') in Rabbinic Judaism. The Masoretic Text defines the Jewish canon and its precise letter-text, with its vocaliz ...

of the Tanakh, that has no etymological connection to ''herem''.

The Talmudic usage of ''herem'' for excommunication can be distinguished from the usage of ''herem'' described in the Tanakh in the time of Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yﺭhﺧﺧ۰uaﮌﺟ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yﺧhﺧﺧ۰uaﮌﺟ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

and the early Hebrew monarchy, which was the practice of consecration by total annihilation at the command of God carried out against peoples such as the Midian

Midian (; ; , ''Madiam''; Taymanitic: ﻭ۹ﻭ۹ﻭ۹ﻭ۹ ''MDYN''; ''Mﺥ،ﻕﺕyﺥn'') is a geographical region in West Asia, located in northwestern Saudi Arabia. mentioned in the Tanakh and Quran. William G. Dever states that biblical Midian was ...

ites, the Amalekites

Amalek (; ) is described in the Hebrew Bible as the enemy of the nation of the Israelites. The name "Amalek" can refer to the descendants of Amalek, the grandson of Esau, or anyone who lived in their territories in Canaan, or North African descend ...

, and the entire population of Jericho

Jericho ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and the capital of the Jericho Governorate. Jericho is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It had a population of 20,907 in 2017.

F ...

. The neglect of Saul

Saul (; , ; , ; ) was a monarch of ancient Israel and Judah and, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament, the first king of the United Monarchy, a polity of uncertain historicity. His reign, traditionally placed in the late eleventh c ...

to carry out such a command as delivered by Samuel

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venera ...

resulted in the selection of David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

as his replacement.

Offenses

The Talmud speaks of twenty-four offenses that, in theory, were punishable by a form of ''niddui'' or temporary excommunication.Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138ﻗ1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

(as well as later authorities) enumerates the twenty-four as follows:

# insulting a learned man, even after his death;

# insulting a messenger of the court;

# calling a fellow Jew a "slave";

# refusing to appear before the court at the appointed time;

# dealing lightly with any of the rabbinic

Rabbinic Judaism (), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, Rabbanite Judaism, or Talmudic Judaism, is rooted in the many forms of Judaism that coexisted and together formed Second Temple Judaism in the land of Israel, giving birth to classical rabb ...

or Mosaic precepts;

# refusing to abide by a decision of the court;

# keeping in one's possession an animal or an object that may prove injurious to others, such as a savage dog or a broken ladder;

# selling one's real estate to a non-Jew without assuming the responsibility for any injury that the non-Jew may cause his neighbors;

# testifying against one's Jewish neighbor in a non-Jewish court, and thereby causing that neighbor to lose money which he would not have lost had the case been decided in a Jewish court;

# a kohen shochet

In Judaism, ''shechita'' (anglicized: ; ; ; also transliterated ''shehitah, shechitah, shehita'') is ritual slaughtering of certain mammals and birds for food according to ''kashrut''. One who practices this, a kosher butcher is called a ''sho ...

(butcher) who refuses to give the foreleg, cheeks and maw

The gift of the foreleg, cheeks and maw () of a kosher-slaughtered animal to a ''kohen'' is a positive mitzva, commandment in the Hebrew Bible. The Shulchan Aruch rules that after the slaughter of animal by a ''shochet'' (kosher slaughterer ...

of kosher-slaughtered livestock to another kohen;

# violating the second day of a holiday, even though its observance is only a custom;

# performing work on the afternoon of the day preceding Passover;

# taking the name of God in vain;

# causing others to profane the name of God;

# causing others to eat holy meat outside of Jerusalem;

# making calculations for the calendar, and establishing festivals accordingly, outside of Israel;

# putting a stumbling-block in the way of the blind, that is to say, tempting another to sin (Lifnei iver

In Judaism, Lifnei Iver (, "Before the Blind") is a Hebrew expression defining a prohibition against misleading people by use of a " stumbling block," or allowing a person to proceed unawares in unsuspecting danger or culpability. The origin comes ...

);

# preventing the community from performing some religious act;

# selling forbidden ("terefah

Terefah (, lit. "torn by a beast of prey"; plural ''treifot'') refers to either:

* A member of a kosher species of mammal or bird, disqualified from being considered kosher, due to pre-existing mortal injuries or physical defects.

* A specific ...

") meat as permitted meat ("kosher");

# failure by a shochet to show his knife to the rabbi for examination;

# purposely bringing oneself to erection;

# engaging in business with one's divorced wife that will lead them to come into contact with each other;

# being made the subject of scandal (in the case of a rabbi);

# declaring an unjustified excommunication.

''Niddui''

The ''niddui'' () ban was usually imposed for a period of seven days (in Israel thirty days). If inflicted on account of money matters, the offender was first publicly warned ("hatra'ah") three times, on Monday, Thursday, and Monday successively, at the regular service in the synagogue. During the period of niddui, no one except the members of his immediate household was permitted to associate with the offender, or to sit within four cubits of him, or to eat in his company. He was expected to go into mourning and to refrain from bathing, cutting his hair, and wearing shoes, and he had to observe all the laws that pertained to a mourner. He could not be counted in theminyan

In Judaism, a ''minyan'' ( ''mﺥ،nyﺥn'' , Literal translation, lit. (noun) ''count, number''; pl. ''mﺥ،nyﺥnﺥ،m'' ) is the quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain Mitzvah, religious obligations. In more traditional streams of Judaism ...

. If he died, a stone was placed on his hearse, and the relatives were not obliged to observe traditional Jewish mourning ceremonies.

It was in the power of the court to lessen or increase the severity of the niddui. The court might even reduce or increase the number of days, forbid all intercourse with the offender, and exclude his children from the schools and his wife from the synagogue, until he became humbled and willing to repent and obey the court's mandates. According to one opinion (recorded in the name of '' Sefer Agudah''), the possibility that the offender might leave the Jewish community due to the severity of the excommunication did not prevent the court from adding rigor

Rigour (British English) or rigor (American English; see spelling differences) describes a condition of stiffness or strictness. These constraints may be environmentally imposed, such as "the rigours of famine"; logically imposed, such as ma ...

to its punishments so as to maintain its dignity and authority.Shulkhan Arukh

The ''Shulhan Arukh'' ( ),, often called "the Code of Jewish Law", is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Rabbinic Judaism. It was authored in the city of Safed in what is now Israel by Joseph Karo in 1563 and published in V ...

, Yoreh De'ah

''Yoreh De'ah'' () is a section of Rabbi Jacob ben Asher's compilation of halakha (Jewish law), the ''Arba'ah Turim'', written around 1300.

This section treats all aspects of Jewish law not pertinent to the Hebrew calendar, finance, torts, marr ...

334:1, Rama's gloss This opinion is vehemently contested by the Taz Taz or TAZ may refer to:

Geography

*Taz (river), a river in western Siberia, Russia

*Taz Estuary, the estuary of the river Taz in Russia

People

* Taz people, an ethnic group in Russia

** Taz language, a form of Northeastern Mandarin spoken by ...

who cites earlier authorities of the same opinion ( Maharshal; Maharam; Mahari Mintz) and presents proof of his position from the Talmud. Additionally, the Taz notes that his edition of the ''Sefer Agudah'' does not contain the cited position.

''Herem''

If the offense was in reference to monetary matters, or if the punishment was inflicted by an individual, the laws were more lenient, the chief punishment being that men might not associate with the offender. At the expiration of the period the ban was lifted by the court. If, however, the excommunicate showed no sign of penitence or remorse, the niddui might be renewed once and again, and finally the "herem," the most rigorous form of excommunication, might be pronounced. This extended for an indefinite period, and no one was permitted to teach the offender or work for him, or benefit him in any way, except when he was in need of the bare necessities of life.''Nezifah''

A milder form than either niddui or herem was the ''nezifah'' ban. (In modern Hebrew, ''nezifah'' generally means "a dressing-down" or "reading (someone) the riot act", i.e., a stern verbal rebuke.) This ban generally only lasted one day. During this time the offender dared not appear before him whom he had displeased. He had to retire to his house, speak little, refrain from business and pleasure, and manifest his regret and remorse. He was not required, however, to separate himself from society, nor was he obliged to apologize to the man whom he had insulted; for his conduct on the day of nezifah was sufficient apology. But when a scholar or prominent man actually pronounced the formal niddui on one who had slighted him, all the laws of niddui applied. This procedure was, however, much discouraged by the sages, so that it was a matter of proper pride for a rabbi to be able to say that he had never pronounced the ban of excommunication. Maimonides concludes with these words the chapter on the laws of excommunication:Cases

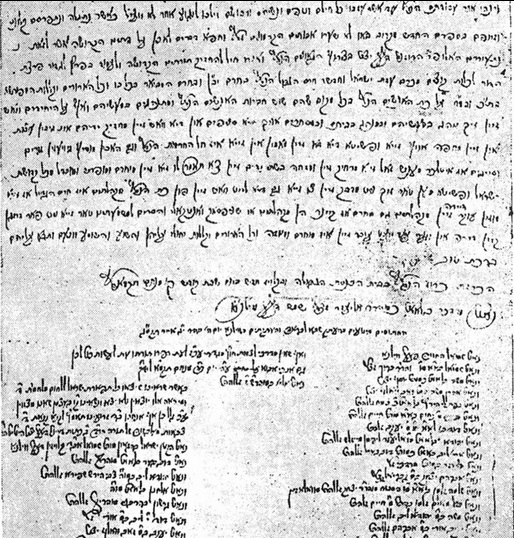

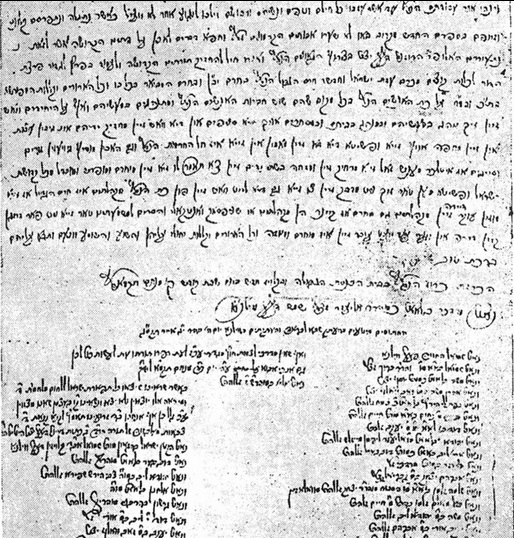

Arguably the most famous case of a herem is that ofBaruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

, the seventeenth-century philosopher.

Another renowned case is the herem the Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman''), also known as the Vilna Gaon ( ''Der Vilner Goen''; ; or Elijah of Vilna, or by his Hebrew acronym Gr"a ("Gaon Rabbenu Eliyahu": "Our great teacher Elijah"; Sialiec, April 23, 172 ...

ruled against the early Hasidic

Hasidism () or Hasidic Judaism is a religious movement within Judaism that arose in the 18th century as a spiritual revival movement in contemporary Western Ukraine before spreading rapidly throughout Eastern Europe. Today, most of those aff ...

movement in 1777 and then again in 1781, under the charge of believing in panentheism

Panentheism (; "all in God", from the Greek , and ) is the belief that the divine intersects every part of the universe and also extends beyond space and time. The term was coined by the German philosopher Karl Krause in 1828 (after reviewin ...

.

Except in rare cases in Haredi

Haredi Judaism (, ) is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that is characterized by its strict interpretation of religious sources and its accepted (Jewish law) and traditions, in opposition to more accommodating values and practices. Its members are ...

communities, ''herem'' stopped existing after the Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'' (; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), often termed the Jewish Enlightenment, was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Wester ...

, when local Jewish communities lost their political autonomy, and Jews were integrated into the gentile nations in which they lived.

* In August 1918, while Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which RussiaﻗUkraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

was ruled by Pavlo Skoropadskyi

Pavlo Petrovych Skoropadskyi (; ﻗ 26 April 1945) was a Ukrainian aristocrat, military and state leader, who served as the Hetman of all Ukraine, hetman of the Ukrainian State throughout 1918 following a 1918 Ukrainian coup d'ﺣ۸tat, coup d'ﺣ۸ta ...

's Second Hetmanate while under Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871ﻗ1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

occupation, the Orthodox Jewish

Orthodox Judaism is a collective term for the traditionalist branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as literally revealed by God on Mount Sinai and faithfully tra ...

rabbi

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbiﻗknown as ''semikha''ﻗfollowing a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of t ...

s of Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehﺣﭘrigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

pronounced the herem against Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( ﻗ 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; ﻗ 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

, and other Jewish Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

.

* In 1945, rabbi Mordecai Kaplan

Mordecai Menahem Kaplan (June 11, 1881 ﻗ November 8, 1983) was an American Conservative rabbi, writer, Jewish educator, professor, theologian, philosopher, activist, and religious leader who founded the Reconstructionist movement of Judaism al ...

, the founder of Reconstructionist Judaism

Reconstructionist Judaism () is a Jewish religious movements, Jewish movement based on the concepts developed by Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan (1881ﻗ1983)ﻗnamely, that Judaism as a Civilization, Judaism is a progressively evolving civilization rather ...

(a Jewish religious movement that seeks to divorce Judaism from belief in a personal deity), was formally excommunicated by the Haredi Union of Orthodox Rabbis

The Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada (UOR), often called by its Hebrew name, Agudath Harabonim or (in Ashkenazi Hebrew) Agudas Harabonim ("union of rabbis"), was established in 1901 in the United States and is the oldest ...

(''Agudath HaRabonim'').

* In 2004, the High Court of South Africa

The High Court of South Africa is a superior court of law in South Africa. It is divided into nine provinces of South Africa, provincial divisions, some of which sit in more than one location. Each High Court division has general jurisdiction ov ...

upheld a herem against a Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

businessman because he refused to pay his former wife alimony

Alimony, also called aliment (Scotland), maintenance (England, Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales, Canada, New Zealand), spousal support (U.S., Canada) and spouse maintenance (Australia), is a legal obligation on a person to provide ...

as ordered by a beth din.

* A herem against members of Neturei Karta

Neturei Karta () is a List of Jewish anti-Zionist organizations, Jewish anti-Zionist organization that advocates Palestinian nationalism. Founded by and for Haredim and Zionism, Haredi Jews opposed to Zionism, it is primarily active in parts o ...

who attended the International Conference to Review the Global Vision of the Holocaust

The International Conference to Review the Global Vision of the Holocaust was a two-day conference in Tehran, Iran, that opened on 11 December 2006. Iranian foreign minister Manouchehr Mottaki said the conference sought "neither to deny nor prove ...

was declared by numerous Haredi religious leaders, including the leaders of the Satmar

Satmar (; ) is a group in Hasidic Judaism founded in 1905 by Grand Rebbe Joel Teitelbaum (1887ﻗ1979), in the city of Szatmﺣ۰rnﺣ۸meti (also called Szatmﺣ۰r in the 1890s), Kingdom of Hungary, Hungary (now Satu Mare in Romania). The group is a b ...

and Chabad

Chabad, also known as Lubavitch, Habad and Chabad-Lubavitch (; ; ), is a dynasty in Hasidic Judaism. Belonging to the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) branch of Orthodox Judaism, it is one of the world's best-known Hasidic movements, as well as one of ...

Hasidic groups.

See also

* Banishment in the Torah *Exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

* Heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

* Heresy in Judaism

Heresy in Judaism refers to those beliefs which contradict the traditional doctrines of Rabbinic Judaism, including theological beliefs and opinions about the practice of ''halakha'' (Jewish religious law). Jewish tradition contains a range of stat ...

* Kareth

The Hebrew term ''kareth'' ("cutting off" , ), or extirpation, is a form of punishment for sin, mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and later Jewish writings. The typical Biblical phrase used is "that soul shall be cut off from its people" or a slight ...

* Ostracism

Ostracism (, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the citizen, ostracism was often us ...

* Pulsa diNura

* Siruv

* Taboo

A taboo is a social group's ban, prohibition or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, offensive, sacred or allowed only for certain people.''Encyclopﺣ۵dia Britannica ...

References

External links

Jewish Encyclopedia 1901: Anathema

Jewish Encyclopedia 1901: Ban

* {{Cite web , url=http://www.roylaw.co.za/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.article&pageID=6218762&ArticleID=7315629 , title=South African High Court upholds Jewish right to pronounce herem , archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130314011604/http://www.roylaw.co.za/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.article&pageID=6218762&ArticleID=7315629 , archive-date=March 14, 2013 Excommunication Jewish courts and civil law Punishments in religion Shunning