|

Shelphs

''Shewanella''-like phosphatases, abbreviated as Shelphs, are a group of enzymes structurally related to protein serine/threonine phosphatases (PPP family). Unlike the canonical subfamilies found in eukaryotes (PP1, PP2A, calcineurin, PP5 and PPEF/PP7), Shelphs span the eukaryote- prokaryote boundary and are found in several genera of Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria), in plants, red algae, fungi and some unicellular parasites, including a causative agent of malaria '' Plasmodium'', ''Cryptosporidium'' and kinetoplastids ('' Trypanosoma'' and ''Leishmania ''Leishmania'' is a parasitic protozoan, a single-celled organism of the genus '' Leishmania'' that are responsible for the disease leishmaniasis. They are spread by sandflies of the genus ''Phlebotomus'' in the Old World, and of the genus '' ...'' species). The prototypic member of the group, a phosphatase from a psychrophilic bacterium ''Shewanella'', has been studied as a model to understand the mechanisms that ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Enzymes

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. Almost all metabolic processes in the cell need enzyme catalysis in order to occur at rates fast enough to sustain life. Metabolic pathways depend upon enzymes to catalyze individual steps. The study of enzymes is called ''enzymology'' and the field of pseudoenzyme analysis recognizes that during evolution, some enzymes have lost the ability to carry out biological catalysis, which is often reflected in their amino acid sequences and unusual 'pseudocatalytic' properties. Enzymes are known to catalyze more than 5,000 biochemical reaction types. Other biocatalysts are catalytic RNA molecules, called ribozymes. Enzymes' specificity comes from their unique three-dimensional structures. Like all catalysts, enzymes increase the reacti ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Kinetoplastids

Kinetoplastida (or Kinetoplastea, as a class) is a group of flagellated protists belonging to the phylum Euglenozoa, and characterised by the presence of an organelle with a large massed DNA called kinetoplast (hence the name). The organisms are commonly referred to as "kinetoplastids" or "kinetoplasts" The group includes a number of parasites responsible for serious diseases in humans and other animals, as well as various forms found in soil and aquatic environments. Their distinguishing feature, the presence of a kinetoplast, is an unusual DNA-containing granule located within the single mitochondrion associated with the base of the cell's flagellum (the basal body). The kinetoplast contains many copies of the mitochondrial genome. The kinetoplastids were first defined by Bronislaw M. Honigberg in 1963 as the members of the flagellated protozoans. They are traditionally divided into the biflagellate Bodonidae and uniflagellate Trypanosomatidae; the former appears to be parap ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in the energy-storage molecules ATP and NADPH while freeing oxygen from water in the cells. The ATP and NADPH is then used to make organic molecules from carbon dioxide in a process known as the Calvin cycle. Chloroplasts carry out a number of other functions, including fatty acid synthesis, amino acid synthesis, and the immune response in plants. The number of chloroplasts per cell varies from one, in unicellular algae, up to 100 in plants like '' Arabidopsis'' and wheat. A chloroplast is characterized by its two membranes and a high concentration of chlorophyll. Other plastid types, such as the leucoplast and the chromoplast, contain little chlorophyll and do not carry out photosynthesis. Chloroplasts are highly dynamic—they ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the Greek ''tyrós'', meaning ''cheese'', as it was first discovered in 1846 by German chemist Justus von Liebig in the protein casein from cheese. It is called tyrosyl when referred to as a functional group or side chain. While tyrosine is generally classified as a hydrophobic amino acid, it is more hydrophilic than phenylalanine. It is encoded by the codons UAC and UAU in messenger RNA. Functions Aside from being a proteinogenic amino acid, tyrosine has a special role by virtue of the phenol functionality. It occurs in proteins that are part of signal transduction processes and functions as a receiver of phosphate groups that are transferred by way of protein kinases. Phosphorylation of the hydroxyl group can change the activity of the targ ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Threonine

Threonine (symbol Thr or T) is an amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and a side chain containing a hydroxyl group, making it a polar, uncharged amino acid. It is essential in humans, meaning the body cannot synthesize it: it must be obtained from the diet. Threonine is synthesized from aspartate in bacteria such as ''E. coli''. It is encoded by all the codons starting AC (ACU, ACC, ACA, and ACG). Threonine sidechains are often hydrogen bonded; the most common small motifs formed are based on interactions with serine: ST turns, ST motifs (often at the beginning of alpha helices) and ST staples (usually at the middle of alpha helices). Modifications The threonine residue is susceptible to numerous posttranslational modifications. The hydroxyl side-chain can ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

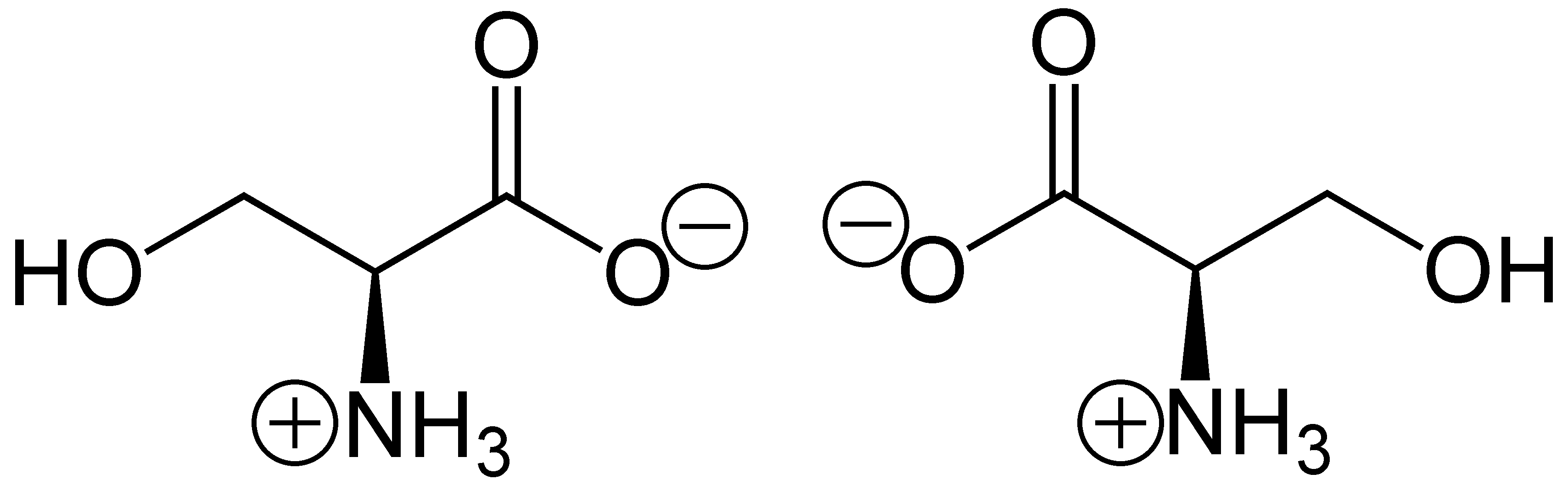

Serine

Serine (symbol Ser or S) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α- amino group (which is in the protonated − form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated − form under biological conditions), and a side chain consisting of a hydroxymethyl group, classifying it as a polar amino acid. It can be synthesized in the human body under normal physiological circumstances, making it a nonessential amino acid. It is encoded by the codons UCU, UCC, UCA, UCG, AGU and AGC. Occurrence This compound is one of the naturally occurring proteinogenic amino acids. Only the L- stereoisomer appears naturally in proteins. It is not essential to the human diet, since it is synthesized in the body from other metabolites, including glycine. Serine was first obtained from silk protein, a particularly rich source, in 1865 by Emil Cramer. Its name is derived from the Latin for silk, ''sericum''. Serine's structure w ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Shewanella

''Shewanella'' is the sole genus included in the marine bacteria family Shewanellaceae. Some species within it were formerly classed as '' Alteromonas''. ''Shewanella'' consists of facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative rods, most of which are found in extreme aquatic habitats where the temperature is very low and the pressure is very high. ''Shewanella'' bacteria are a normal component of the surface flora of fish and are implicated in fish spoilage. ''Shewanella chilikensis'', a species of the genus ''Shewanella'' commonly found in the marine sponges of Saint Martin's Island of the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. ''Shewanella oneidensis'' MR-1 is a widely used laboratory model to study anaerobic respiration of metals and other anaerobic extracellular electron acceptors, and for teaching about microbial electrogenesis and microbial fuel cells. Biochemical characteristics of ''Shewanella'' species Colony, morphological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics of ''Shewanel ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Psychrophilic

Psychrophiles or cryophiles (adj. ''psychrophilic'' or ''cryophilic'') are extremophilic organisms that are capable of growth and reproduction in low temperatures, ranging from to . They have an optimal growth temperature at . They are found in places that are permanently cold, such as the polar regions and the deep sea. They can be contrasted with thermophiles, which are organisms that thrive at unusually high temperatures, and mesophiles at intermediate temperatures. Psychrophile is Greek for 'cold-loving', . Many such organisms are bacteria or archaea, but some eukaryotes such as lichens, snow algae, phytoplankton, fungi, and wingless midges, are also classified as psychrophiles. Biology Habitat The cold environments that psychrophiles inhabit are ubiquitous on Earth, as a large fraction of the planetary surface experiences temperatures lower than 10 °C. They are present in permafrost, polar ice, glaciers, snowfields and deep ocean waters. These organisms can als ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Leishmania

''Leishmania'' is a parasitic protozoan, a single-celled organism of the genus '' Leishmania'' that are responsible for the disease leishmaniasis. They are spread by sandflies of the genus ''Phlebotomus'' in the Old World, and of the genus ''Lutzomyia'' in the New World. At least 93 sandfly species are proven or probable vectors worldwide.WHO (2010) Annual report. Geneva Their primary hosts are vertebrates; ''Leishmania'' commonly infects hyraxes, canids, rodents, and humans. History Members of an ancient genus of the ''Leishmania'' parasite, ''Paleoleishmania'', have been detected in fossilized sand flies dating back to the early Cretaceous period. The first written reference to the conspicuous symptoms of cutaneous leishmaniasis surfaced in the Paleotropics within oriental texts dating back to the 7th century BC (allegedly transcribed from sources several hundred years older, between 1500 and 2000 BC). Due to its broad and persistent prevalence throughout antiquity as a mys ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Trypanosoma

''Trypanosoma'' is a genus of kinetoplastids (class Trypanosomatidae), a monophyletic group of unicellular parasitic flagellate protozoa. Trypanosoma is part of the phylum Sarcomastigophora. The name is derived from the Greek ''trypano-'' (borer) and ''soma'' (body) because of their corkscrew-like motion. Most trypanosomes are heteroxenous (requiring more than one obligatory host to complete life cycle) and most are transmitted via a vector. The majority of species are transmitted by blood-feeding invertebrates, but there are different mechanisms among the varying species. Some, such as ''Trypanosoma equiperdum'', are spread by direct contact. In an invertebrate host they are generally found in the intestine, but normally occupy the bloodstream or an intracellular environment in the vertebrate host. Trypanosomes infect a variety of hosts and cause various diseases, including the fatal human diseases sleeping sickness, caused by '' Trypanosoma brucei'', and Chagas diseas ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cryptosporidium

''Cryptosporidium'', sometimes informally called crypto, is a genus of apicomplexan parasitic alveolates that can cause a respiratory and gastrointestinal illness ( cryptosporidiosis) that primarily involves watery diarrhea (intestinal cryptosporidiosis), sometimes with a persistent cough (respiratory cryptosporidiosis). Treatment of gastrointestinal infection in humans involves fluid rehydration, electrolyte replacement, and management of any pain. , nitazoxanide is the only drug approved for the treatment of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent hosts. Supplemental zinc may improve symptoms, particularly in recurrent or persistent infections or in others at risk for zinc deficiency. ''Cryptosporidium'' oocysts are 4–6 μm in diameter and exhibit partial acid-fast staining. They must be differentiated from other partially acid-fast organisms including '' Cyclospora cayetanensis''. General characteristics ''Cryptosporidium'' causes cryptosporidiosis, an infe ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Phosphatase

In biochemistry, a phosphatase is an enzyme that uses water to cleave a phosphoric acid monoester into a phosphate ion and an alcohol. Because a phosphatase enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of its substrate, it is a subcategory of hydrolases. Phosphatase enzymes are essential to many biological functions, because phosphorylation (e.g. by protein kinases) and dephosphorylation (by phosphatases) serve diverse roles in cellular regulation and signaling. Whereas phosphatases remove phosphate groups from molecules, kinases catalyze the transfer of phosphate groups to molecules from ATP. Together, kinases and phosphatases direct a form of post-translational modification that is essential to the cell's regulatory network. Phosphatase enzymes are not to be confused with phosphorylase enzymes, which catalyze the transfer of a phosphate group from hydrogen phosphate to an acceptor. Due to their prevalence in cellular regulation, phosphatases are an area of interest for pharmaceutical re ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |