|

Middle Persian Literature

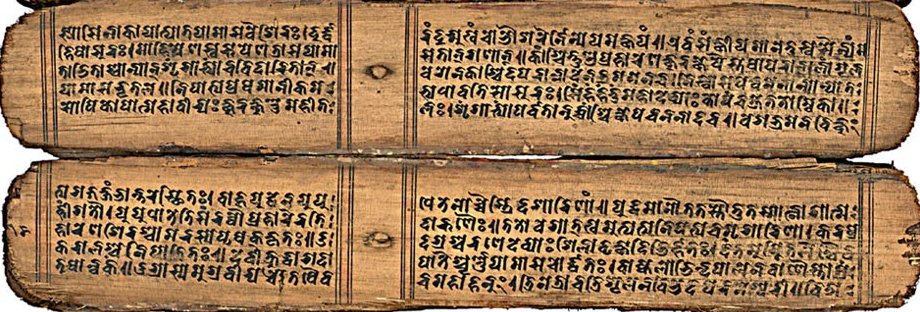

Middle Persian literature is the corpus of written works composed in Middle Persian, that is, the Middle Iranian dialect of Persis, Persia proper, the region in the south-western corner of the Iranian plateau. Middle Persian was the prestige dialect during the era of Sasanian dynasty. It is the largest source of Zoroastrian literature. The rulers of the Sasanian Empire (224–654 CE) were natives of that south-western region, and through their political and cultural influence, Middle Persian became a prestige dialect and thus also came to be used by non-Persian Iranians. Following the Muslim conquest of Persia, Arab conquest of the Sassanian Empire in the 7th century, shortly after which Middle Persian began to evolve into New Persian, Middle Persian continued to be used by the Zoroastrian priesthood for religious and secular compositions. These compositions, in the Aramaic-derived Book Pahlavi script, are traditionally known as "Pahlavi literature". The earliest texts in Zoroastr ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Middle Persian

Middle Persian, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg ( Inscriptional Pahlavi script: , Manichaean script: , Avestan script: ) in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle Persian continued to function as a prestige language. It descended from Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenid Empire and is the linguistic ancestor of Modern Persian, the official language of Iran (also known as Persia), Afghanistan ( Dari) and Tajikistan ( Tajik). Name "Middle Iranian" is the name given to the middle stage of development of the numerous Iranian languages and dialects. The middle stage of the Iranian languages begins around 450 BCE and ends around 650 CE. One of those Middle Iranian languages is Middle Persian, i.e. the middle stage of the language of the Persians, an Iranian people of Persia proper, which lies in the south-western Iran highlands on ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ma'na Of Pars

Mana, also known as Mana of Pars, Mana of Rev Ardashir or Mana of Shiraz, was a Persian Christian theologian, author and an East Syriac metropolitan bishop of Pars during the 5th and 6th centuries AD. Mana is chiefly noted for the translation of Syriac and Greek Christian literature into Pahlavi language. He is the first Christian writer known to have written in Pahlavi and is generally attributed with the translation of the Pahlavi Psalter from the Syriac Peshitta. Identity The biography of Mana is largely shrouded in mystery due to the unavailability of clear and complete historical documentation. There has been significant degree of confusion in determining his identity due to the fact that a number of different individuals have been known by the name Mana in the 5th and 6th centuries in the East Syriac church. These include Mana, an East Syriac catholicos, as well as another individual known as Mana Shirazi. The chief sources for Mana include, the Chronicle of Seert, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Jamasp Namag

The Jamasp Nameh (var: ''Jāmāsp Nāmag'', ''Jāmāsp Nāmeh'', "Story of Jamasp") is a Middle Persian book of revelations. In an extended sense, it is also a primary source on Medieval Zoroastrian doctrine and legend. The work is also known as the ''Ayādgār ī Jāmāspīg'' or ''Ayātkār-ī Jāmāspīk'', meaning " nMemoriam of Jamasp". The text takes the form of a series of questions and answers between Vishtasp and Jamasp, both of whom were amongst Zoroaster's immediate and closest disciples. Vishtasp was the princely protector and patron of Zoroaster while Jamasp was a nobleman at Vishtasp's court. Both are figures mentioned in the Gathas, the oldest hymns of Zoroastrianism and believed to have been composed by Zoroaster. Here (chap. 3.6-7) there occurs a striking theological statement, that Ohrmazd’s creation of the seven Amašaspands was like lamps being lit one from another, none being diminished thereby. The text has survived in three forms: * a Pahlavi manus ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Wisdom Literature

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. Although this genre uses techniques of traditional oral storytelling, it was disseminated in written form. The earliest known wisdom literature dates back to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, originating from ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. These regions continued to produce wisdom literature over the subsequent two and a half millennia. Wisdom literature from Jewish, Greek, Chinese, and Indian cultures started appearing around the middle of the 1st millennium BC. In the 1st millennium AD, Egyptian-Greek wisdom literature emerged, some elements of which were later incorporated into Islamic thought. Much of wisdom literature can be broadly categorized into two types – conservative "positive wisdom" and critical "negative wisdom" or "vanity literature": * Conservative Positive Wisdom – Pragmatic, r ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Menog-i Khrad

The ''Mēnōg-ī Khrad'' () or ''Spirit of Wisdom'' is one of the most important secondary texts in Zoroastrianism written in Middle Persian. Also transcribed in Pazend as ''Minuy-e X(e/a)rad'' and in New Persian ''Minu-ye Xeræd'', the text is a Zoroastrian Pahlavi book in sixty-three chapters (a preamble and sixty-two questions and answers), in which a symbolic character called Dānāg (lit., “knowing, wise”) poses questions to the personified Spirit of Wisdom, who is extolled in the preamble and identified in two places (2.95, 57.4) with innate wisdom (''āsn xrad''). The book, like most Middle Persian books, is based on oral tradition and has no known author. According to the preamble, Dānāg, searching for truth, traveled to many countries, associated himself with many savants, and learned about various opinions and beliefs. When he discovered the virtue of ''xrad'' (1.51), the Spirit of Wisdom appeared to him to answer his questions. The book belongs to the genre of ''a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Book Of Arda Viraf

The ''Book of Arda Viraf'' (Middle Persian: ''Ardā Wirāz nāmag'', lit. 'Book of the Righteous Wirāz') is a Zoroastrian text written in Middle Persian. It contains about 8,800 words. It describes the dream-journey of a devout Zoroastrian (the Wirāz of the story) through the next world. The text assumed its definitive form in the 11th-12th centuries after a series of redactions and it is probable that the story was an original product of 9th-10th century Pars. Title ''Ardā'' (cf. aša (pronounced ''arta'') cognate with Sanskrit ''ṛta'') is an epithet of Wirāz and is approximately translatable as "truthful, righteous, just." ''Wirāz'' is probably akin to Proto-Indo-European *''wiHro-''-, "man", cf. Persian: ''bīr'' Avestan: ''vīra''. Given the ambiguity inherent to Pahlavi scripts in the representing the pronunciation of certain consonants, ''Wirāz'', the name of the protagonist, may also be transliterated as ''Wiraf'' or ''Viraf'', but the Avestan form is clearly ' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Epistles Of Manushchihr

The ''Epistles of Manushchihr'' (Minocher) () are a response to comments made by the author's brother on the subject of purification in Zoroastrianism. When Zadsparam, who was the high priest of Sirjan which is located near Kerman, proposed certain new precepts, the public were not ready for change and were very unsatisfied. Therefore, they decided to complain to the high priest's older brother Manuschchihr, who was the high priest of Kerman. In response, Manushchihr issued three epistle An epistle (; ) is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part of the scribal-school writing curriculum. The ...s in the issue: #A reply to the complaining people #an expostulation with his brother #a public decree condemning the new precepts of his younger brother as unlawful innovations. The first epistle is dated March 15, 881; the third is dated Ju ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dadestan-i Denig

( "Religious Judgments") or ( "Book of Questions") is a 9th-century Middle Persian work written by Manuščihr, who was high priest of the Persian Zoroastrian community of Pārs and Kermān, son of Juvānjam and brother of Zādspram. The work consists of an introduction and ninety-two questions along with Manuščihr's answers. His questions varies from religious to social, ethical, legal, philosophical, cosmological, etc. The style of his work is abstruse, dense, and is heavily influenced by New Persian New Persian (), also known as Modern Persian () is the current stage of the Persian language spoken since the 8th to 9th centuries until now in Greater Iran and surroundings. It is conventionally divided into three stages: Early New Persian (8th .... References External linksFull text in English Middle Persian Middle Persian literature Zoroastrian texts Iranian books {{Zoroastrianism-book-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe. Overview Scientific theories In astronomy, cosmogony is the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in reference to the origin of the universe, the Solar System, or the Earth–Moon system. The prevalent physical cosmology, cosmological scientific theory, model of the early development of the universe is the Big Bang theory. Sean M. Carroll, who specializes in Physical cosmology, theoretical cosmology and Field (physics), field theory, explains two competing explanations for the origins of the Gravitational singularity, singularity, which is the center of a space in which a characteristic is limitless (one example is the singularity of a black hole, where gravity is the characteristic that becomes infinite). It is generally accepted that the universe began at a point of singularity. When the universe started to expand, the Big Bang occurred, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bundahishn

The ''Bundahishn'' (Middle Persian: , "Primal Creation") is an encyclopedic collection of beliefs about Zoroastrian cosmology written in the Book Pahlavi script. The original name of the work is not known. It is one of the most important extant witnesses to Zoroastrian literature in the Middle Persian language. Although the ''Bundahishn'' draws on the Avesta and develops ideas alluded to in those texts, it is not itself scripture. The content reflects Zoroastrian scripture, which, in turn, reflects both ancient Zoroastrian and pre-Zoroastrian beliefs. In some cases, the text alludes to contingencies of post-7th century Islam in Iran, and in yet other cases, such as the idea that the Moon is farther than the stars. Structure The ''Bundahishn'' survives in two recensions: an Indian and an Iranian version. The shorter version was found in India and contains only 30 chapters, and is thus known as the ''Lesser Bundahishn'', or ''Indian Bundahishn''. A copy of this version was broug ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Denkard

The ''Dēnkard'' or ''Dēnkart'' (Middle Persian: 𐭣𐭩𐭭𐭪𐭠𐭫𐭲 "Acts of Religion") is a 10th-century compendium of Zoroastrian beliefs and customs during the time. The ''Denkard'' has been called an "Encyclopedia of Mazdaism" and is a valuable source of Zoroastrian literature especially during its Middle Persian iteration. The ''Denkard'' is not considered a sacred text by a majority of Zoroastrians, but is still considered worthy of study. Name The name traditionally given to the compendium reflects a phrase from the colophons, which speaks of the /, from Avestan meaning "acts" (also in the sense of "chapters"), and , from Avestan , literally "insight" or "revelation", but more commonly translated as "religion." Accordingly, means "religious acts" or "acts of religion." The ambiguity of or in the title reflects the orthography of Pahlavi writing, in which the letter may sometimes denote /d/. Date and authorship The individual chapters vary in age, style ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sacred Language

A sacred language, liturgical language or holy language is a language that is cultivated and used primarily for religious reasons (like church service) by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives. Some religions, or parts of them, regard the language of their sacred texts as in itself sacred. These include Ecclesiastical Latin in Roman Catholicism, Hebrew in Judaism, Arabic in Islam, Avestan in Zoroastrianism, Sanskrit in Hinduism, and Punjabi in Sikhism. By contrast Buddhism and Christian denominations outside of Catholicism do not generally regard their sacred languages as sacred in themselves. Concept A sacred language is often the language which was spoken and written in the society in which a religion's sacred texts were first set down; these texts thereafter become fixed and holy, remaining frozen and immune to later linguistic developments. (An exception to this is Lucumí, a ritual lexicon of the Cuban strain of the Santería religion, with no ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |