|

General Linear Position

In algebraic geometry and computational geometry, general position is a notion of genericity for a set of points, or other geometric objects. It means the ''general case'' situation, as opposed to some more special or coincidental cases that are possible, which is referred to as special position. Its precise meaning differs in different settings. For example, generically, two lines in the plane intersect in a single point (they are not parallel or coincident). One also says "two generic lines intersect in a point", which is formalized by the notion of a ''generic point''. Similarly, three generic points in the plane are not collinear; if three points are collinear (even stronger, if two coincide), this is a degenerate case. This notion is important in mathematics and its applications, because degenerate cases may require an exceptional treatment; for example, when stating general theorems or giving precise statements thereof, and when writing computer programs (see '' generic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Algebraic Geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics which uses abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, to solve geometry, geometrical problems. Classically, it studies zero of a function, zeros of multivariate polynomials; the modern approach generalizes this in a few different aspects. The fundamental objects of study in algebraic geometry are algebraic variety, algebraic varieties, which are geometric manifestations of solution set, solutions of systems of polynomial equations. Examples of the most studied classes of algebraic varieties are line (geometry), lines, circles, parabolas, ellipses, hyperbolas, cubic curves like elliptic curves, and quartic curves like lemniscate of Bernoulli, lemniscates and Cassini ovals. These are plane algebraic curves. A point of the plane lies on an algebraic curve if its coordinates satisfy a given polynomial equation. Basic questions involve the study of points of special interest like singular point of a curve, singular p ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Vector Space

In mathematics and physics, a vector space (also called a linear space) is a set (mathematics), set whose elements, often called vector (mathematics and physics), ''vectors'', can be added together and multiplied ("scaled") by numbers called scalar (mathematics), ''scalars''. The operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication must satisfy certain requirements, called ''vector axioms''. Real vector spaces and complex vector spaces are kinds of vector spaces based on different kinds of scalars: real numbers and complex numbers. Scalars can also be, more generally, elements of any field (mathematics), field. Vector spaces generalize Euclidean vectors, which allow modeling of Physical quantity, physical quantities (such as forces and velocity) that have not only a Magnitude (mathematics), magnitude, but also a Orientation (geometry), direction. The concept of vector spaces is fundamental for linear algebra, together with the concept of matrix (mathematics), matrices, which ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Divisor (algebraic Geometry)

In algebraic geometry, divisors are a generalization of codimension-1 subvarieties of algebraic varieties. Two different generalizations are in common use, Cartier divisors and Weil divisors (named for Pierre Cartier and André Weil by David Mumford). Both are derived from the notion of divisibility in the integers and algebraic number fields. Globally, every codimension-1 subvariety of projective space is defined by the vanishing of one homogeneous polynomial; by contrast, a codimension-''r'' subvariety need not be definable by only ''r'' equations when ''r'' is greater than 1. (That is, not every subvariety of projective space is a complete intersection.) Locally, every codimension-1 subvariety of a smooth variety can be defined by one equation in a neighborhood of each point. Again, the analogous statement fails for higher-codimension subvarieties. As a result of this property, much of algebraic geometry studies an arbitrary variety by analysing its codimension-1 subvarieti ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Algebraic Curve

In mathematics, an affine algebraic plane curve is the zero set of a polynomial in two variables. A projective algebraic plane curve is the zero set in a projective plane of a homogeneous polynomial in three variables. An affine algebraic plane curve can be completed in a projective algebraic plane curve by homogenization of a polynomial, homogenizing its defining polynomial. Conversely, a projective algebraic plane curve of homogeneous equation can be restricted to the affine algebraic plane curve of equation . These two operations are each inverse function, inverse to the other; therefore, the phrase algebraic plane curve is often used without specifying explicitly whether it is the affine or the projective case that is considered. If the defining polynomial of a plane algebraic curve is irreducible polynomial, irreducible, then one has an ''irreducible plane algebraic curve''. Otherwise, the algebraic curve is the union of one or several irreducible curves, called its ''Irreduc ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cayley–Bacharach Theorem

In mathematics, the Cayley–Bacharach theorem is a statement about cubic curves (plane curves of degree three) in the projective plane . The original form states: :Assume that two cubics and in the projective plane meet in nine (different) points, as they do in general over an algebraically closed field. Then every cubic that passes through any eight of the points also passes through the ninth point. A more intrinsic form of the Cayley–Bacharach theorem reads as follows: :Every cubic curve over an algebraically closed field that passes through a given set of eight points also passes through (counting multiplicities) a ninth point which depends only on . A related result on conics was first proved by the French geometer Michel Chasles and later generalized to cubics by Arthur Cayley and Isaak Bacharach. Details If seven of the points lie on a conic, then the ninth point can be chosen on that conic, since will always contain the whole conic on account of Bézout's the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

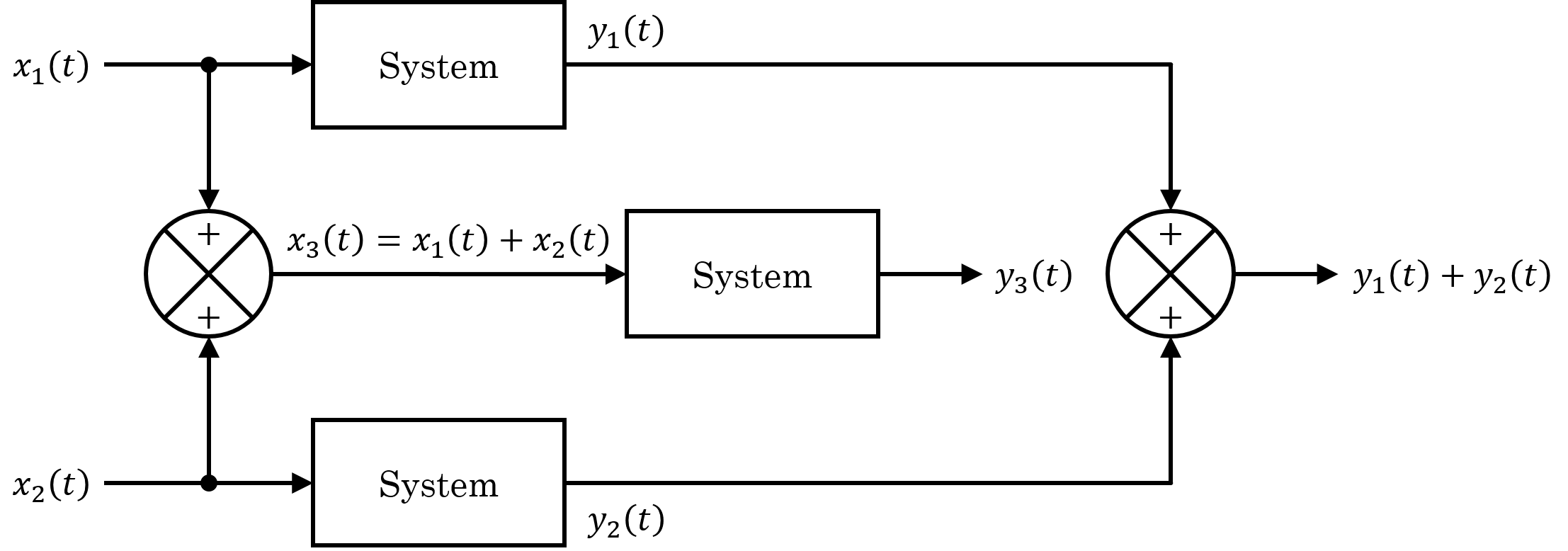

Linear System

In systems theory, a linear system is a mathematical model of a system based on the use of a linear operator. Linear systems typically exhibit features and properties that are much simpler than the nonlinear case. As a mathematical abstraction or idealization, linear systems find important applications in automatic control theory, signal processing, and telecommunications. For example, the propagation medium for wireless communication systems can often be modeled by linear systems. Definition A general deterministic system can be described by an operator, , that maps an input, , as a function of to an output, , a type of black box description. A system is linear if and only if it satisfies the superposition principle, or equivalently both the additivity and homogeneity properties, without restrictions (that is, for all inputs, all scaling constants and all time.) The superposition principle means that a linear combination of inputs to the system produces a linear com ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pencil (mathematics)

In geometry, a pencil is a family of geometric objects with a common property, for example the set of Line (geometry), lines that pass through a given point in a plane (mathematics), plane, or the set of circles that pass through two given points in a plane. Although the definition of a pencil is rather vague, the common characteristic is that the pencil is completely determined by any two of its members. Analogously, a set of geometric objects that are determined by any three of its members is called a bundle. Thus, the set of all lines through a point in three-space is a bundle of lines, any two of which determine a pencil of lines. To emphasize the two-dimensional nature of such a pencil, it is sometimes referred to as a ''flat pencil''. Any geometric object can be used in a pencil. The common ones are lines, planes, circles, conics, spheres, and general curves. Even points can be used. A pencil of points is the set of all points on a given line. A more common term for this ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bézout's Theorem

In algebraic geometry, Bézout's theorem is a statement concerning the number of common zeros of polynomials in indeterminates. In its original form the theorem states that ''in general'' the number of common zeros equals the product of the degrees of the polynomials. It is named after Étienne Bézout. In some elementary texts, Bézout's theorem refers only to the case of two variables, and asserts that, if two plane algebraic curves of degrees d_1 and d_2 have no component in common, they have d_1d_2 intersection points, counted with their multiplicity, and including points at infinity and points with complex coordinates. In its modern formulation, the theorem states that, if is the number of common points over an algebraically closed field of projective hypersurfaces defined by homogeneous polynomials in indeterminates, then is either infinite, or equals the product of the degrees of the polynomials. Moreover, the finite case occurs almost always. In the case of ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Veronese Map

The Veronese map of degree 2 is a mapping from \R^ to the space of symmetric matrices (n+1)(n+1) defined by the formula: :V\colon(x_0,\dots,x_n)\to \begin x_0\cdot x_0&x_0\cdot x_1&\dots&x_0\cdot x_n \\ x_1\cdot x_0&x_1\cdot x_1&\dots&x_1\cdot x_n \\ \vdots&\vdots&\ddots&\vdots \\ x_n\cdot x_0&x_n\cdot x_1&\dots&x_n\cdot x_n \end. Note that V(x)=V(-x) for any x\in\R^. In particular, the restriction of V to the unit sphere \mathbb^n factors through the projective space \R\mathrm^n, which defines the Veronese embedding of \R\mathrm^n. The image of the Veronese embedding is called the Veronese submanifold, and for n=2 it is known as the Veronese surface. Properties *The matrices in the image of the Veronese embedding correspond to projections onto one-dimensional subspaces in \R^. They can be described by the equations: *:A^T=A,\quad \mathrm\,A=1,\quad A^2=A. :In other words, the matrices in the image of \R\mathrm^n have unit trace and unit norm. Specifically, the following is true: :* ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Conic Section

A conic section, conic or a quadratic curve is a curve obtained from a cone's surface intersecting a plane. The three types of conic section are the hyperbola, the parabola, and the ellipse; the circle is a special case of the ellipse, though it was sometimes considered a fourth type. The ancient Greek mathematicians studied conic sections, culminating around 200 BC with Apollonius of Perga's systematic work on their properties. The conic sections in the Euclidean plane have various distinguishing properties, many of which can be used as alternative definitions. One such property defines a non-circular conic to be the set of those points whose distances to some particular point, called a '' focus'', and some particular line, called a ''directrix'', are in a fixed ratio, called the ''eccentricity''. The type of conic is determined by the value of the eccentricity. In analytic geometry, a conic may be defined as a plane algebraic curve of degree 2; that is, as the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Five Points Determine A Conic

In Euclidean geometry, Euclidean and projective geometry, five points determine a conic (a degree-2 plane curve), just as two (distinct) Point (geometry), points determine a line (geometry), line (a degree-1 plane curve). There are additional subtleties for conics that do not exist for lines, and thus the statement and its proof for conics are both more technical than for lines. Formally, given any five points in the plane in general linear position, meaning no three collinear, there is a unique conic passing through them, which will be non-Degenerate conic, degenerate; this is true over both the Euclidean plane and any Pappian plane, pappian projective plane. Indeed, given any five points there is a conic passing through them, but if three of the points are collinear the conic will be degenerate (reducible, because it contains a line), and may not be unique; see Degenerate conic#Points to define, further discussion. Proofs This result can be proven numerous different ways; the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |