|

Collodaria

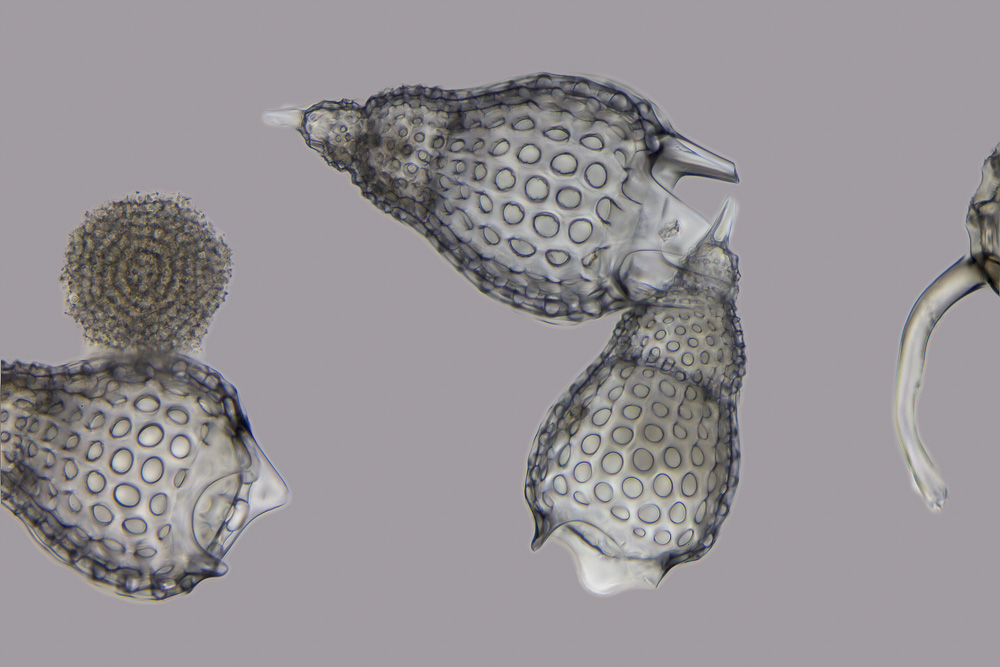

Collodaria is a unicellular order (organisms within the order are called Collodarians) under the phylum Radiozoa (or Radiolaria) and the infrakingdom Rhizaria. Like most of the Radiolaria taxonomy, Collodaria was first described by Ernst Haeckel, a German scholar who published three volumes of manuscript describing the extensive samples of Radiolaria collected by the voyage of HMS ''Challenger''. Recent molecular phylogenetic studies concluded that there are Collodaria contains three families, Sphaerozodae, Collosphaeridae, and Collophidilidae. Story and origin Ernst Haeckel is the main contributor to species description in the phylum Radiolaria, which contains the order Collodaria. Members of Collodaria were first described in 1862. In 1881, ''Collodaria'' was defined by Haeckel in 1881 as “ Spumellaria without latticed shell.” The story behind this order involved the historic voyage of HMS ''Challenger''. As recorded in the manuscript of "Report on the Scientific Resu ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Radiolarian Orders

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are unicellular eukaryotes of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The elaborate mineral skeleton is usually made of silica. They are found as zooplankton throughout the global ocean. As zooplankton, radiolarians are primarily heterotrophic, but many have photosynthetic endosymbionts and are, therefore, considered mixotrophs. The skeletal remains of some types of radiolarians make up a large part of the cover of the ocean floor as siliceous ooze. Due to their rapid change as species and intricate skeletons, radiolarians represent an important diagnostic fossil found from the Cambrian onwards. Description Radiolarians have many needle-like pseudopods supported by bundles of microtubules, which aid in the radiolarian's buoyancy. The cell nucleus and most other organelles are in the endoplasm, while th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Radiolaria

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are unicellular eukaryotes of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The elaborate mineral skeleton is usually made of silica. They are found as zooplankton throughout the global ocean. As zooplankton, radiolarians are primarily heterotrophic, but many have photosynthetic endosymbionts and are, therefore, considered mixotrophs. The skeletal remains of some types of radiolarians make up a large part of the cover of the ocean floor as siliceous ooze. Due to their rapid change as species and intricate skeletons, radiolarians represent an important diagnostic fossil found from the Cambrian onwards. Description Radiolarians have many needle-like pseudopods supported by bundles of microtubules, which aid in the radiolarian's buoyancy. The cell nucleus and most other organelles are in the endoplasm, wh ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Polycystine

The polycystines are a group of radiolarians. They include the vast majority of the fossil radiolaria, as their skeletons are abundant in marine sediments, making them one of the most common groups of microfossils. These skeletons are composed of opaline silica. In some it takes the form of relatively simple spicules, but in others it forms more elaborate lattices, such as concentric spheres with radial spines or sequences of conical chambers. Two of the orders belonging to this group are the radially-symmetrical Spumellaria, dating back to the late Cambrian period, and the bilaterally-symmetrical Nasselaria, whose origin is placed within the lower Devonian The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per .... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Carbon Fixation

Biological carbon fixation, or сarbon assimilation, is the Biological process, process by which living organisms convert Total inorganic carbon, inorganic carbon (particularly carbon dioxide, ) to Organic compound, organic compounds. These organic compounds are then used to store energy and as structures for other Biomolecule, biomolecules. Carbon is primarily fixed through photosynthesis, but some organisms use chemosynthesis in the absence of sunlight. Chemosynthesis is carbon fixation driven by chemical energy rather than from sunlight. The process of biological carbon fixation plays a crucial role in the global carbon cycle, as it serves as the primary mechanism for removing from the atmosphere and incorporating it into Biomass (ecology), living biomass. The primary production of organic compounds allows carbon to enter the biosphere. Carbon is considered essential for life as a base element for building organic compounds. The flow of carbon from the Earth's atmosphere, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Taxopodida

''Sticholonche'' is a genus of radiolarians with a single species, ''Sticholonche zanclea'', found in open oceans at depths of 99–510 metres. It is generally considered a heliozoan, placed in its own order, called the Taxopodida. However it has also been classified as an unusual radiolarian, and this has gained support from genetic studies, which place it near the Acantharea. ''Sticholonche'' are usually around 200 Micrometre, μm, though this varies considerably, and have a bilaterally symmetric shape, somewhat flattened and widened at the front. The axopods are arranged into distinct rows, six of which lie in a dorsal groove and are rigid, and the rest of which are mobile. These are used primarily for buoyancy, rather than feeding. They also have fourteen groups of prominent spines, and many smaller wikt:spicule, spicules, although there is no central capsule as in true radiolarians. References Further reading * Radiolarian genera Monotypic eukaryote gene ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Paraphyly

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In contrast, a monophyletic grouping (a clade) includes a common ancestor and ''all'' of its descendants. The terms are commonly used in phylogenetics (a subfield of biology) and in the tree model of historical linguistics. Paraphyletic groups are identified by a combination of synapomorphies and symplesiomorphies. If many subgroups are missing from the named group, it is said to be polyparaphyletic. The term received currency during the debates of the 1960s and 1970s accompanying the rise of cladistics, having been coined by zoologist Willi Hennig to apply to well-known taxa like Reptilia (reptiles), which is paraphyletic with respect to birds. Reptilia contains the last common ancestor of reptiles and all descendants of that ancest ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Nassellaria

Nassellaria is an order of Rhizaria belonging to the class Radiolaria. The organisms of this order are characterized by a skeleton cross link with a cone or ring. Introduction Nassellaria is an order of Radiolaria under the class Polycystina. These organisms are unicellular eukaryotic heterotrophic plankton typically with a siliceous cone-shaped skeleton. The most common group of radiolarians are the polycystine radiolarians, which are divided into two subgroups: the spumellarians and the nassellarians. Both spumellarians and nassellarians are common chert-forming microfossils and are important in stratigraphical dating, as the oldest radiolarians are Precambrian in age. The nassellarians appear in the fossil record much later than their other polycystine relatives, the spumellarians. spumellarians can be seen as far back as the Precambrian, whereas nassellarians do not begin to appear until the Carboniferous. Nassellarians are believed to have been increasing in species diver ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Sticholonche

''Sticholonche'' is a genus of radiolarians with a single species, ''Sticholonche zanclea'', found in open oceans at depths of 99–510 metres. It is generally considered a heliozoan, placed in its own order, called the Taxopodida. However it has also been classified as an unusual radiolarian, and this has gained support from genetic studies, which place it near the Acantharea The Acantharia are a group of radiolarian protozoa, distinguished mainly by their strontium sulfate skeletons. Acantharians are heterotrophic marine Plankton, microplankton that range in size from about 200 microns in diameter up to several milli .... ''Sticholonche'' are usually around 200 μm, though this varies considerably, and have a bilaterally symmetric shape, somewhat flattened and widened at the front. The axopods are arranged into distinct rows, six of which lie in a dorsal groove and are rigid, and the rest of which are mobile. These are used primarily for buoyancy, rather than feeding. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Acantharea

The Acantharia are a group of radiolarian protozoa, distinguished mainly by their strontium sulfate skeletons. Acantharians are heterotrophic marine Plankton, microplankton that range in size from about 200 microns in diameter up to several millimeters. Some acantharians have photosynthetic endosymbionts and hence are considered mixotrophs. Morphology Acantharian skeletons are composed of strontium sulfate, SrSO4, in the form of mineral Celestine (mineral), celestine crystal. Celestine is named for the delicate blue colour of its crystals, and is the heaviest mineral in the ocean. The denseness of their celestite ensures acantharian shells function as Ballast minerals, mineral ballast, resulting in fast sedimentation to bathypelagic, bathypelagic depths. High settling flux, fluxes of acantharian cysts have been observed at times in the Iceland Basin and the Southern Ocean, as much as half of the total gravitational organic carbon flux. Material was copied from this source, whic ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Paleozoic

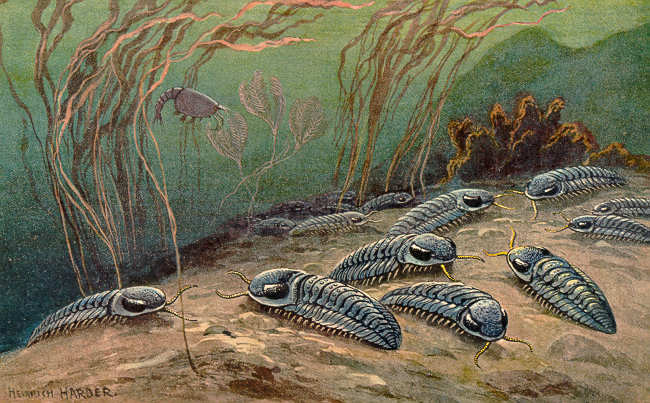

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma at the start of the Mesozoic Era. The Paleozoic is subdivided into six period (geology), geologic periods (from oldest to youngest), Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian. Some geological timescales divide the Paleozoic informally into early and late sub-eras: the Early Paleozoic consisting of the Cambrian, Ordovician and Silurian; the Late Paleozoic consisting of the Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian. The name ''Paleozoic'' was first used by Adam Sedgwick (1785–1873) in 1838 to describe the Cambrian and Ordovician periods. It was redefined by John Phillips (geologist), John Phillips (1800–1874) in 1840 to cover the Cambrian to Permian periods. It is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek ''palaiós'' (π� ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Micropaleontology

Micropaleontology (American spelling; spelled micropalaeontology in European usage) is the branch of paleontology (palaeontology) that studies microfossils, or fossils that require the use of a microscope to see the organism, its morphology and its characteristic details. Microfossils Microfossils are fossils that are generally between 0.001mm and 1 mm in size, the study of which requires the use of light or electron microscopy. Fossils which can be studied by the naked eye or low-powered magnification, such as a hand lens, are referred to as macrofossils. For example, some colonial organisms, such as Bryozoa (especially the Cheilostomata) have relatively large colonies, but are classified by fine skeletal details of the small individuals of the colony. In another example, many fossil genera of Foraminifera, which are protists are known from shells (called "tests") that were as big as coins, such as the genus '' Nummulites''. Microfossils are a common feature of th ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Axopodium

A pseudopod or pseudopodium (: pseudopods or pseudopodia) is a temporary arm-like projection of a eukaryotic cell membrane that is emerged in the direction of movement. Filled with cytoplasm, pseudopodia primarily consist of actin filaments and may also contain microtubules and intermediate filaments. Pseudopods are used for motility and ingestion. They are often found in amoebas. Different types of pseudopodia can be classified by their distinct appearances. Lamellipodia are broad and thin. Filopodia are slender, thread-like, and are supported largely by microfilaments. Lobopodia are bulbous and amoebic. Reticulopodia are complex structures bearing individual pseudopodia which form irregular nets. Axopodia are the phagocytosis type with long, thin pseudopods supported by complex microtubule arrays enveloped with cytoplasm; they respond rapidly to physical contact. Generally, several pseudopodia arise from the surface of the body, (''polypodial'', for example, ''Amoeba proteus' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |