Volcanology of Canada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 2,677‑million-year-old

The 2,677‑million-year-old  The 1884- to 1870‑million-year-old

The 1884- to 1870‑million-year-old  During the

During the  Periods of volcanic activity occurred throughout central Canada during the

Periods of volcanic activity occurred throughout central Canada during the  The

The

The Canadian portion of the

The Canadian portion of the  After the sedimentary and igneous rocks were folded and crushed, it resulted in the creation of a new continental shelf and coastline. The Insular Plate continued to subduct under the new continental shelf and coastline about 130 million years ago during the mid

After the sedimentary and igneous rocks were folded and crushed, it resulted in the creation of a new continental shelf and coastline. The Insular Plate continued to subduct under the new continental shelf and coastline about 130 million years ago during the mid  The Farallon Plate continued to subduct under the new continental margin of Western Canada after the Insular Plate and Insular Islands collided with the former continental margin, supporting a new chain of volcanoes on the mainland of Western Canada called the

The Farallon Plate continued to subduct under the new continental margin of Western Canada after the Insular Plate and Insular Islands collided with the former continental margin, supporting a new chain of volcanoes on the mainland of Western Canada called the  One of the major aspects that changed early during the Coast Range Arc was the status of the northern end of the Farallon Plate, a portion now known as the

One of the major aspects that changed early during the Coast Range Arc was the status of the northern end of the Farallon Plate, a portion now known as the

As the last of the Kula Plate decayed and the Farallon Plate advanced back into this area from the south, it once again started to subduct under the continental margin of Western Canada 37 million years ago, supporting a chain of volcanoes called the

As the last of the Kula Plate decayed and the Farallon Plate advanced back into this area from the south, it once again started to subduct under the continental margin of Western Canada 37 million years ago, supporting a chain of volcanoes called the

The four-million-year-old

The four-million-year-old  The

The

The

The  The

The  The

The  The Endeavour Segment, an active rift zone of the larger

The Endeavour Segment, an active rift zone of the larger

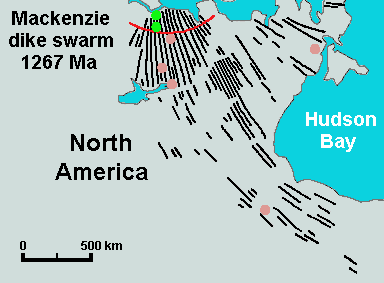

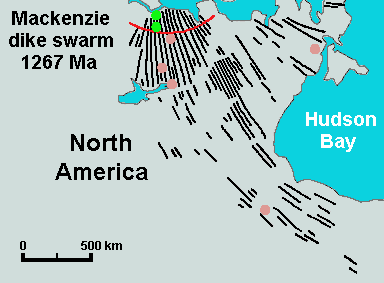

Vast volumes of basaltic lava covered Northern Canada in the form of a

Vast volumes of basaltic lava covered Northern Canada in the form of a  The

The

The predominantly volcanic Archean and Proterozoic

The predominantly volcanic Archean and Proterozoic

The kimberlite

The kimberlite

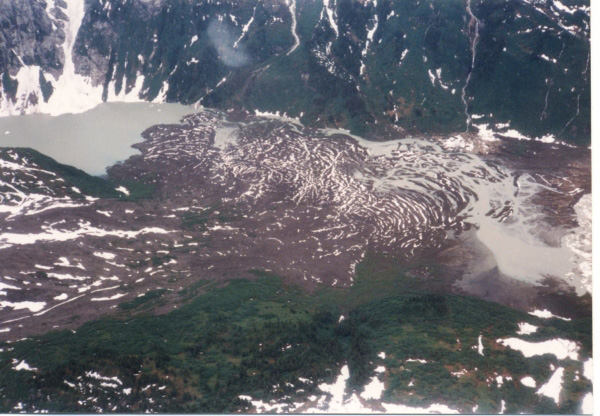

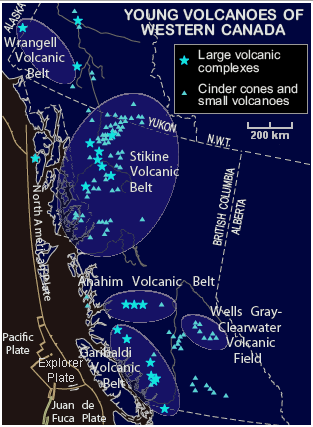

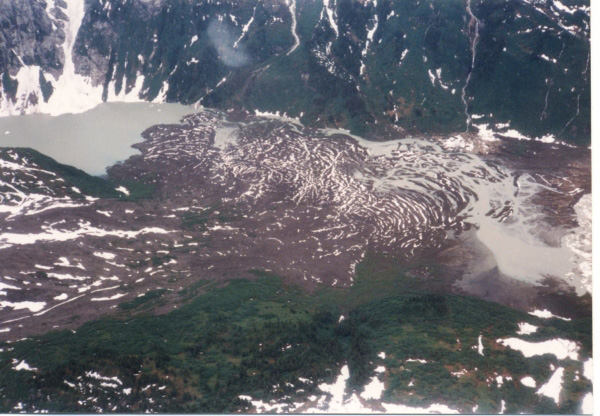

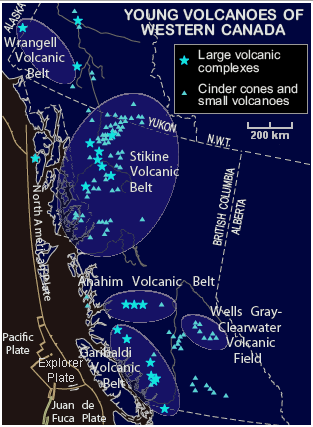

The Mount Meager massif in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt of southwestern British Columbia was the source for a massive ( VEI-5) Plinian eruption 2,350 years ago similar in character to the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in the U.S. state of

The Mount Meager massif in the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt of southwestern British Columbia was the source for a massive ( VEI-5) Plinian eruption 2,350 years ago similar in character to the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in the U.S. state of  The massive Mount Edziza volcanic complex in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province of northern British Columbia has had more than 20 eruptions throughout the past 10,000 years (Holocene), including Mess Lake Cone,

The massive Mount Edziza volcanic complex in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province of northern British Columbia has had more than 20 eruptions throughout the past 10,000 years (Holocene), including Mess Lake Cone,

Volcanic activity

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

is a major part of the geology of Canada

The geology of Canada is a subject of regional geology and covers the country of Canada, which is the second-largest country in the world. Geologic units and processes are investigated on a large scale to reach a synthesized picture of the geolog ...

and is characterized by many types of volcanic landform

A landform is a natural or anthropogenic land feature on the solid surface of the Earth or other planetary body. Landforms together make up a given terrain, and their arrangement in the landscape is known as topography. Landforms include hills, ...

, including lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or un ...

flows, volcanic plateau

A volcanic plateau is a plateau produced by volcanic activity. There are two main types: lava plateaus and pyroclastic plateaus.

Lava plateau

Lava plateaus are formed by highly fluid basaltic lava during numerous successive eruptions throu ...

s, lava dome

In volcanology, a lava dome is a circular mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. Dome-building eruptions are common, particularly in convergent plate boundary settings. Around 6% of eruptions on ...

s, cinder cone

A cinder cone (or scoria cone) is a steep conical hill of loose pyroclastic fragments, such as volcanic clinkers, volcanic ash, or scoria that has been built around a volcanic vent. The pyroclastic fragments are formed by explosive eruptions o ...

s, stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a conical volcano built up by many layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with a summit crater and per ...

es, shield volcano

A shield volcano is a type of volcano named for its low profile, resembling a warrior's shield lying on the ground. It is formed by the eruption of highly fluid (low viscosity) lava, which travels farther and forms thinner flows than the more v ...

es, submarine volcano

Submarine volcanoes are underwater vents or fissures in the Earth's surface from which magma can erupt. Many submarine volcanoes are located near areas of tectonic plate formation, known as mid-ocean ridges. The volcanoes at mid-ocean ridges ...

es, caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

s, diatreme

A diatreme, sometimes known as a maar-diatreme volcano, is a volcanic pipe formed by a gaseous explosion. When magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the ...

s, and maar

A maar is a broad, low-relief volcanic crater caused by a phreatomagmatic eruption (an explosion which occurs when groundwater comes into contact with hot lava or magma). A maar characteristically fills with water to form a relatively shallow ...

s, along with less common volcanic forms such as tuya

A tuya is a flat-topped, steep-sided volcano formed when lava erupts through a thick glacier or ice sheet. They are rare worldwide, being confined to regions which were covered by glaciers and had active volcanism during the same period.

As lava ...

s and subglacial mound

A subglacial mound (SUGM) is a type of subglacial volcano. This type of volcano forms when lava erupts beneath a thick glacier or ice sheet. The magma forming these volcanoes was not hot enough to melt a vertical pipe right through the overlying ...

s.

Though Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

's volcanic history dates back to the Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of the ...

eon, at least 3.11 billion years ago, when its part of the North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

n continent began to form, volcanism continues to occur in Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Northern Canada

Northern Canada, colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three Provinces_and_territories_of_Canada#Territories, territor ...

in modern times, where it forms part of an encircling chain of volcanoes and frequent earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

s around the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

called the Pacific Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many Types of volcanic eruptions, volcanic eruptions and ...

. Because volcanoes in Western and Northern Canada are in relatively remote and sparsely populated areas and their activity is less frequent than with other volcanoes around the Pacific Ocean, Canada is commonly thought to occupy a gap in the Ring of Fire between the volcanoes of the western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

to the south and the Aleutian volcanoes of Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

to the north. Even so, the mountainous landscapes of the Canadian provinces of Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

, British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, Yukon Territory

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

, and the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

include more than 100 volcanoes that have been active during the past two million years and whose eruptions have claimed many lives.

Volcanic activity is responsible for many of Canada's geological and geographical features and mineralization, including the nucleus of the North American continent, known as the Canadian Shield

The Canadian Shield (french: Bouclier canadien ), also called the Laurentian Plateau, is a geologic shield, a large area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks. It forms the North American Craton (or Laurentia), the anc ...

. Volcanism has led to the formation of hundreds of volcanic areas and extensive lava formations across Canada. The country's different volcano and lava types originate from different tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents k ...

settings and types of volcanic eruptions

Several types of volcanic eruptions—during which lava, tephra (ash, lapilli, volcanic bombs and volcanic blocks), and assorted gases are expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure—have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are oft ...

, ranging from passive lava eruptions to violent explosive eruption

In volcanology, an explosive eruption is a volcanic eruption of the most violent type. A notable example is the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Such eruptions result when sufficient gas has dissolved under pressure within a viscous magma such ...

s. Canada has a rich record of very large volumes of magmatic rock called large igneous province

A large igneous province (LIP) is an extremely large accumulation of igneous rocks, including intrusive (sills, dikes) and extrusive (lava flows, tephra deposits), arising when magma travels through the crust towards the surface. The formation ...

s, represented by deep-level plumbing systems consisting of giant dike swarm

A dike swarm (American spelling) or dyke swarm (British spelling) is a large geological structure consisting of a major group of parallel, linear, or radially oriented magmatic dikes intruded within continental crust or central volcanoes ...

s, sill provinces and layered intrusion

In geology, an igneous intrusion (or intrusive body or simply intrusion) is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and com ...

s. The most capable large igneous provinces in Canada are Archean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth

Earth ...

greenstone belt

Greenstone belts are zones of variably metamorphosed mafic to ultramafic volcanic sequences with associated sedimentary rocks that occur within Archaean and Proterozoic cratons between granite and gneiss bodies.

The name comes from the green ...

s estimated at 3.8 to 2.5 billion years old, containing a rare volcanic rock called komatiite.

Eruption styles and volcano formations

Eastern Canada

The 2,677‑million-year-old

The 2,677‑million-year-old Abitibi greenstone belt

The Abitibi greenstone belt is a 2,800-to-2,600-million-year-old greenstone belt that spans across the Ontario–Quebec border in Canada. It is mostly made of volcanic rocks, but also includes ultramafic rocks, mafic intrusions, granitoid rocks, ...

in Ontario and Quebec is one of the largest Archean greenstone belts on Earth and one of the youngest parts of the Superior craton

The Superior Craton is a stable crustal block covering Quebec, Ontario, and southeast Manitoba in Canada, and northern Minnesota in the United States. It is the biggest craton among those formed during the Archean period. A craton is a large part ...

which sequentially forms part of the Canadian Shield.

Komatiite lavas in the Abitibi greenstone belt (pictured) occur in four lithotectonic assemblages known as Pacaud, Stoughton-Roquemaure, Kidd-Munro and Tisdale. The Swayze greenstone belt The Swayze greenstone belt is a late Archean greenstone belt in northern Ontario, Canada. It is the southwestern extension of the Abitibi greenstone belt.

See also

*Volcanism of Canada

*Volcanism of Eastern Canada

*List of volcanoes in Canada

*List ...

further south is interpreted to be a southwestern extension of the Abitibi greenstone belt.

The Archean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth

Earth ...

Red Lake greenstone belt The Red Lake greenstone belt is an Archean greenstone belt at the town of Red Lake in Northwestern Ontario, Canada. It consists of basaltic and komatiitic volcanics ranging in age from 2,925 to 2,940 million years old and younger rhyolit ...

in western Ontario consists of basaltic and komatiitic volcanics ranging in age from 2,925 to 2,940 million years old and younger rhyolite-andesite volcanics ranging in age from 2,730 to 2,750 million years old. It is situated in the western portion of the Uchi Subprovince The Uchi Subprovince is a Neoarchean volcanic sequence in Manitoba, Canada. It is at the southern margin of the North Caribou terrane and comprises a number of greenstone belts, which contains volcanic rocks that record some 280 million years of vol ...

, a volcanic sequence comprising a number of greenstone belts.

The 1884- to 1870‑million-year-old

The 1884- to 1870‑million-year-old Circum-Superior Belt

The Circum-Superior Belt is a widespread Paleoproterozoic large igneous province in the Canadian Shield of Northern, Western and Eastern Canada. It extends more than from northeastern Manitoba through northwestern Ontario, southern Nunavut to ...

constitutes a large igneous province extending for more than from the Labrador Trough

The Labrador Trough or the New Quebec Orogen is a long and wide geologic belt in Canada, extending south-southeast from Ungava Bay through Quebec and Labrador.

The trough is a linear belt of sedimentary and volcanic rocks which developed in an ...

in Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

and northeastern Quebec though the Cape Smith Belt The Cape Smith Belt is an early Proterozoic thrust belt in northern Quebec, Canada.

References

Geology of Quebec

{{Canada-geology-stub ...

in northern Quebec, the Belcher Islands

The Belcher Islands ( iu, script=latn, ᓴᓪᓚᔪᒐᐃᑦ, Sanikiluaq) are an archipelago in the southeast part of Hudson Bay near the centre of the Nastapoka arc. The Belcher Islands are spread out over almost . Administratively, they belon ...

in southern Nunavut

Nunavut ( , ; iu, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ , ; ) is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' ...

, the Fox River and Thompson

Thompson may refer to:

People

* Thompson (surname)

* Thompson M. Scoon (1888–1953), New York politician

Places Australia

*Thompson Beach, South Australia, a locality

Bulgaria

* Thompson, Bulgaria, a village in Sofia Province

Canada

* ...

belts in northern Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

, the Winnipegosis komatiite belt

The Winnipegosis komatiite belt is a long and wide greenstone belt located in the Lake Winnipegosis area of central Manitoba, Canada. It has no surface exposure and was identified based on geophysical signatures and drilling during mineral e ...

in central Manitoba, and on the southern side of the Superior craton in the Animikie Basin of northwestern Ontario. Two volcano-sedimentary sequences exist in the Labrador Trough with ages of 2,170–2,140 million years and 1,883–1,870 million years. In the Cape Smith Belt, two volcanic group

A volcanic group is a stratigraphic group consisting of volcanic strata. They can be in the form of volcanic fields, volcanic complexes and cone

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequ ...

s range in age from 2,040 to 1,870 million years old called the Povungnituk volcano-sedimentary Group and the Chukotat Group. The Belcher Islands in eastern Hudson Bay contain two volcanic sequences known as the Flaherty and Eskimo volcanics. The Fox River Belt consists of volcanics, sills and sediments some 1,883 million years old while magmatism of the Thompson Belt is dated to 1,880 million years old. To the south lies the 1,864‑million-year-old Winnipegosis komatiites. In the Animikie Basin near Lake Superior, volcanism is dated 1,880 million years old.

During the

During the Mesoproterozoic

The Mesoproterozoic Era is a geologic era that occurred from . The Mesoproterozoic was the first era of Earth's history for which a fairly definitive geological record survives. Continents existed during the preceding era (the Paleoproterozoic), ...

era of the Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of the ...

eon 1,109 million years ago, northwestern Ontario began to split apart to form the Midcontinent Rift System

The Midcontinent Rift System (MRS) or Keweenawan Rift is a long geological rift in the center of the North American continent and south-central part of the North American plate. It formed when the continent's core, the North American craton, ...

, also called the Keweenawan Rift. Lava flows created by the rift in the Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

area were formed from basaltic magma. The upwelling of this magma was the result of a hotspot which produced a triple junction

A triple junction is the point where the boundaries of three tectonic plates meet. At the triple junction each of the three boundaries will be one of three types – a ridge (R), trench (T) or transform fault (F) – and triple junctions can b ...

in the vicinity of Lake Superior. The hotspot made a dome that covered the Lake Superior area. Voluminous basaltic lava flows erupted from the central axis of the rift, similar to the rifting that formed the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

. A '' failed arm'' extends north into mainland Ontario where it forms a geological formation known as the Nipigon Embayment. This failed arm includes Lake Nipigon

Lake Nipigon (; french: lac Nipigon; oj, Animbiigoo-zaaga'igan) is part of the Great Lakes drainage basin. It is the largest lake entirely within the boundaries of the Canadian province of Ontario.

Etymology

In the Jesuit Relations the lake is ...

, the largest lake entirely within the boundaries of Ontario.

Periods of volcanic activity occurred throughout central Canada during the

Periods of volcanic activity occurred throughout central Canada during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

and Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

periods. The source for this volcanism was a long-lived and stationary area of molten rock called the New England or Great Meteor hotspot. The first event erupted kimberlite magma in the James Bay

James Bay (french: Baie James; cr, ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, Wînipekw, dirty water) is a large body of water located on the southern end of Hudson Bay in Canada. Both bodies of water extend from the Arctic Ocean, of which James Bay is the southernmost par ...

lowlands region of northern Ontario 180 million years ago, creating the Attawapiskat kimberlite field The Attawapiskat kimberlite field is a field of kimberlite pipes located astride the Attawapiskat River in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, in Northern Ontario, Canada. It is thought to have formed about 180 million years ago in the Jurassic period when the ...

. Another kimberlite event spanned a period of 13 million years 165 to 152 million years ago, creating the Kirkland Lake kimberlite field The Kirkland Lake kimberlite field is a 165 to 152 million year old kimberlite field in the Kirkland Lake area of northeastern Ontario, Canada.

See also

*Volcanism of Canada

* Volcanism of Eastern Canada

*List of volcanoes in Canada

List of volc ...

in northeastern Ontario. Another period of kimberlite volcanism occurred in northeastern Ontario 154 to 134 million years ago, creating the Lake Timiskaming kimberlite field. As the North American Plate moved westward over the New England hotspot, the New England hotspot created the magma intrusion

In geology, an igneous intrusion (or intrusive body or simply intrusion) is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and com ...

s of the Monteregian Hills

The Monteregian Hills (french: Collines Montérégiennes) is a linear chain of isolated hills in Montreal and Montérégie, between the Laurentians and the Appalachians.

Etymology

The first definition of the Monteregian Hills came about in 190 ...

in Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

in southern Quebec. These intrusive stocks have been variously interpreted as the feeder intrusions of long extinct volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

es that would have been active 125 million years ago, or as intrusions that never breached the surface in volcanic activity. The lack of a noticeable hotspot track west of the Monteregian Hills might be due either to failure of the New England mantle plume to pass through massive strong rock of the Canadian Shield, the lack of noticeable intrusions, or to strengthening of the New England mantle plume when it approached the Monteregian Hills region.

About 250 million years ago during the early Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

period, Atlantic Canada lay roughly in the middle of a giant continent called Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

. This supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continent, continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", ...

began to fracture 220 million years ago when the Earth's lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust (geology), crust and the portion of the upper mantle (geology), mantle that behaves elastically on time sca ...

was being pulled apart from extensional stress, creating a divergent plate boundary

In plate tectonics, a divergent boundary or divergent plate boundary (also known as a constructive boundary or an extensional boundary) is a linear feature that exists between two tectonic plates that are moving away from each other. Divergent b ...

known as the Fundy Basin

The Fundy Basin is a sediment-filled rift basin on the Atlantic coast of southeastern Canada. It contains three sub-basins; the Fundy sub-basin, the Minas Basin and the Chignecto Basin. These arms meet at the Bay of Fundy, which is contained with ...

. The focus of the rifting began somewhere between where present-day eastern North America and northwestern Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

were joined. During the formation of the Fundy Basin, volcanic activity never stopped as shown by the going eruption of lava along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North Ame ...

; an underwater volcanic mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

formed as a result of continuous seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

between eastern North America and northwestern Africa. As the Fundy Basin continued to form 201 million years ago, a series of basaltic lava flows were erupted, forming a volcanic mountain range on the mainland portion of southwestern Nova Scotia known as North Mountain, stretching from Brier Island

Brier Island is an island in the Bay of Fundy in Digby County, Nova Scotia.

Geography

The island is the westernmost part of Nova Scotia and the southern end of the North Mountain ridge with Long Island lying immediately northeast; both islands ...

in the south to Cape Split

Cape Split is a headland located on the Bay of Fundy coast of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. The Battle off Cape Split happened during the American Revolution.

Cape Split is located in Kings County and is a continuation of the North Mo ...

in the north. This series of lava flows cover most of the Fundy Basin and extend under the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy (french: Baie de Fundy) is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its extremely high tidal range is the hi ...

where parts of it are exposed on the shore at the rural community of Five Islands, east of Parrsboro

Parrsboro is a community located in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

A regional service centre for southern Cumberland County, the community is also known for its port on the Minas Basin, the Ship's Company Theatre productions, and t ...

on the north side of the bay. Large dikes wide exist throughout southernmost New Brunswick with ages and compositions similar to the North Mountain basalt, indicating these dikes were the source for North Mountain lava flows. However, North Mountain is the remnants of a larger volcanic feature that has now been largely eroded based on the existence of basin border faults and erosion. The hard basaltic ridge of North Mountain resisted the grinding of ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at Las ...

s that flowed over this region during the past ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

s, and now forms one side of the Annapolis Valley

The Annapolis Valley is a valley and region in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. It is located in the western part of the Nova Scotia peninsula, formed by a trough between two parallel mountain ranges along the shore of the Bay of Fundy. St ...

in the western part of the Nova Scotia peninsula

The Nova Scotia peninsula is a peninsula on the Atlantic coast of North America.

Location

The Nova Scotia peninsula is part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada and is connected to the neighbouring province of New Brunswick through the Isth ...

. The layering of a North Mountain lava flow less than thick at McKay Head, closely resemble that of some Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

an lava lake

Lava lakes are large volumes of molten lava, usually basaltic, contained in a volcanic vent, crater, or broad depression. The term is used to describe both lava lakes that are wholly or partly molten and those that are solidified (sometim ...

s, indicating Hawaiian eruption

A Hawaiian eruption is a type of volcanic eruption where lava flows from the vent in a relatively gentle, low level eruption; it is so named because it is characteristic of Hawaiian volcanoes. Typically they are effusive eruptions, with basaltic ...

s occurred during the formation of North Mountain.

The

The Fogo Seamounts

The Fogo Seamounts, also called the Fogo Seamount Chain, are a group of undersea mountains southeast of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in the North Atlantic Ocean. This seamount chain, lying approximately offshore from the island of Newfoundla ...

, located offshore of Newfoundland to the southwest of the Grand Banks

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, swordf ...

, consists of submarine volcanoes with dates extending back to the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous ( geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pro ...

period at least 143 million years ago. They may have one or two origins. The Fogo Seamounts could have formed along fracture zones in the Atlantic seafloor because of the large number of seamounts on the North American continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

. The other explanation for their origin is they formed above a mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

associated with the Canary

Canary originally referred to the island of Gran Canaria on the west coast of Africa, and the group of surrounding islands (the Canary Islands). It may also refer to:

Animals Birds

* Canaries, birds in the genera ''Serinus'' and ''Crithagra'' i ...

or Azores hotspot

The Azores hotspot is a volcanic hotspot in the Northern Atlantic Ocean. The Azores is relatively young and is associated with a bathymetric swell, a gravity anomaly and ocean island basalt geochemistry. The Azores hotspot lies just east of the ...

s in the Atlantic Ocean, based on the existence of older seamounts to the northwest and younger seamounts to the southeast. The existence of flat-topped seamounts throughout the Fogo Seamount chain indicate some of these seamounts would once have stood above sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

as islands that would have been volcanically active. Their flatness is due to coastal erosion, such as waves and winds. Other submarine volcanoes offshore of Eastern Canada include the poorly studied Newfoundland Seamounts

The Newfoundland Seamounts are a group of seamounts offshore of Eastern Canada in the northern Atlantic Ocean. Named for the island of Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland, this group of seamounts formed during the Cretaceous period and are poorly ...

.

Western Canada

TheFlin Flon greenstone belt

The Flin Flon greenstone belt, also referred to as the Flin Flon – Snow Lake greenstone belt, is a Precambrian greenstone belt located in the central area of Manitoba and east-central Saskatchewan, Canada (near Flin Flon). It lies in the central ...

in central Manitoba and east-central Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

is a collage of deformed volcanic arc

A volcanic arc (also known as a magmatic arc) is a belt of volcanoes formed above a subducting oceanic tectonic plate,

with the belt arranged in an arc shape as seen from above. Volcanic arcs typically parallel an oceanic trench, with the arc lo ...

rocks ranging in age from 1,904 to 1,864 million years old during the Paleoproterozoic

The Paleoproterozoic Era (;, also spelled Palaeoproterozoic), spanning the time period from (2.5–1.6 Ga), is the first of the three sub-divisions (eras) of the Proterozoic Eon. The Paleoproterozoic is also the longest era of the Earth's ...

sub-division of the Precambrian eon. Volcanic activity between 1,890 and 1,864 million years ago produced calc-alkaline

The calc-alkaline magma series is one of two main subdivisions of the subalkaline magma series, the other subalkaline magma series being the tholeiitic series. A magma series is a series of compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic mag ...

andesite-rhyolite magmas and rare shoshonite

Shoshonite is a type of igneous rock. More specifically, it is a potassium-rich variety of basaltic trachyandesite, composed of olivine, augite and plagioclase phenocrysts in a groundmass with calcic plagioclase and sanidine and some dark-colored v ...

and trachyandesite magmas while the 1,904‑million-year-old arc volcanism occurred in one or more separate volcanic arcs that were possibly characterized by rapid subduction of thin oceanic crust and large back-arc basin

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic basin, found at some convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found in the western Pacific Ocean. Most of ...

s. In contrast, the younger 1,890‑million-year-old volcanics indicate evidence of crustal thickening. This was due to long-term growth of the volcanic arcs by continuous volcanic activity and tectonic thickening associated with arc collisions and successive arc deformation. This in turn followed a massive mountain building event called the Trans-Hudson orogeny

The Trans-Hudson orogeny or Trans-Hudsonian orogeny was the major mountain building event (orogeny) that formed the Precambrian Canadian Shield and the North American Craton (also called Laurentia), forging the initial North American continen ...

.

The Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

period 145-66 million years ago was a period for active kimberlite volcanism in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin

The Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) underlies of Western Canada including southwestern Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan, Alberta, northeastern British Columbia and the southwest corner of the Northwest Territories. This vast sedimentary ...

of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The Fort à la Corne kimberlite field in central Saskatchewan formed 104 to 95 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous ( geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pro ...

. Unlike most kimberlite fields on Earth, the Fort à la Corne kimberlite field formed during more than one eruptive event. Its kimberlites are among the most complete examples on Earth, preserving kimberlite pipes and maar

A maar is a broad, low-relief volcanic crater caused by a phreatomagmatic eruption (an explosion which occurs when groundwater comes into contact with hot lava or magma). A maar characteristically fills with water to form a relatively shallow ...

volcanoes. The Northern Alberta kimberlite province

The northern Alberta kimberlite province (NAKP) consists of three groups of diatremes or volcanic pipes in northern Alberta, north-central Alberta, Canada, most of which are kimberlites and some of which are diamondiferous. They are called the ...

consists of three kimberlite fields known as the Birch Mountains

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

, Buffalo Head Hills and the Mountain Lake cluster

The Mountain Lake cluster consists of two diatremes or volcanic pipes in Northern Alberta, Canada. It was emplaced during a period of kimberlite volcanism in the Late Cretaceous epoch.

Although they were originally described as kimberlite or kimb ...

. The Birch Mountains kimberlite field consists of eight kimberlite pipes known as Phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

, Dragon

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as ...

, Xena

Xena is a fictional character from Robert Tapert's '' Xena: Warrior Princess'' franchise. Co-created by Tapert and John Schulian, she first appeared in the 1995–1999 television series ''Hercules: The Legendary Journeys'', before going on to ...

, Legend

A legend is a Folklore genre, genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived, both by teller and listeners, to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human valu ...

and Valkyrie

In Norse mythology, a valkyrie ("chooser of the slain") is one of a host of female figures who guide souls of the dead to the god Odin's hall Valhalla. There, the deceased warriors become (Old Norse "single (or once) fighters"Orchard (1997:36) ...

, dating approximately 75 million years old. The Buffalo Head Hills kimberlite field was dominated by explosive kimberlite volcanism from 88 million years ago to 81 million years ago, forming maar

A maar is a broad, low-relief volcanic crater caused by a phreatomagmatic eruption (an explosion which occurs when groundwater comes into contact with hot lava or magma). A maar characteristically fills with water to form a relatively shallow ...

s. Kimberlites of the Buffalo Head Hills field are similar to those associated with the Fort à la Corne kimberlite field in central Saskatchewan. The kimberlite pipes of the Mountain Lake cluster were formed during a similar timespan with the Birch Mountains field 77 million years ago.

Formation of the Pacific Northwest

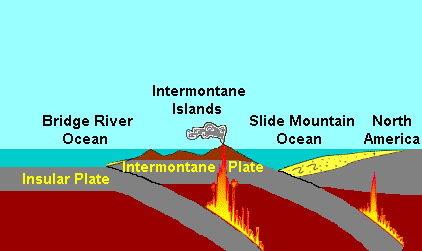

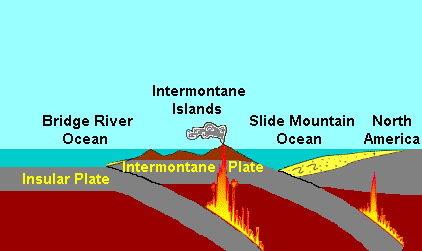

The Canadian portion of the

The Canadian portion of the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

began forming during the early Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

period when a group of active volcanic islands collided against a pre-existing continental margin

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges. The continental margin ...

and coastline of Western Canada. These volcanic islands, known as the Intermontane Islands

The Intermontane Islands were a giant chain of active volcanic islands somewhere in the Pacific Ocean during the Triassic time beginning around 245 million years ago. They were 600 to long and rode atop a microplate known as the Intermontane Plate ...

by geoscientists, were formed on a pre-existing tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large te ...

called the Intermontane Plate

The Intermontane Plate was an ancient oceanic tectonic plate that lay on the west coast of North America about 195 million years ago. The Intermontane Plate was surrounded by a chain of volcanic islands called the Intermontane Islands, which had b ...

about 245 million years ago by subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

of the former Insular Plate to its west during the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

period. This subduction zone records another subduction zone called the Intermontane Trench

The Intermontane Trench was an ancient oceanic trench during the Triassic. The trench was probably long, parallel to the west coast of North America. The ocean that the trench was located in was called the Slide Mountain Ocean.

See also

*Inter ...

under an ancient ocean between the Intermontane Islands and the former continental margin of Western Canada called the Slide Mountain Ocean

The Slide Mountain Ocean was an ancient ocean that existed between the Intermontane Islands and North America beginning around 245 million years ago in the Triassic period. It is named after the Slide Mountain Terrane, which is composed of rocks f ...

. This arrangement of two parallel subduction zones is unusual in that very few twin subduction zones exist on Earth; the Philippine Mobile Belt

In the geology of the Philippines, the Philippine Mobile Belt is a complex portion of the tectonic boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the Philippine Sea Plate, comprising most of the country of the Philippines. It includes two subduction z ...

off the eastern coast of Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

is an example of a modern twin subduction zone. As the Intermontane Plate drew closer to the pre-existing continental margin by ongoing subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

under the Slide Mountain Ocean, the Intermontane Islands drew closer to the former continental margin and coastline of Western Canada, supporting a volcanic arc on the former continental margin of Western Canada. As the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

drifted west and the Intermontane Plate continued to drift east to the ancient continental margin of Western Canada, the Slide Mountain Ocean began to close by ongoing subduction under the Slide Mountain Ocean. This subduction zone eventually jammed and shut down completely about 180 million years ago, ending the arc volcanism on the ancient continental margin of Western Canada and the Intermontane Islands collided, forming a long chain of deformed volcanic and sedimentary rock called the Intermontane Belt

The Intermontane Belt is a physiogeological region in the Pacific Northwest of North America, stretching from northern Washington into British Columbia, Yukon, and Alaska. It comprises rolling hills, high plateaus and deeply cut valleys. The roc ...

, which consists of deeply cut valleys, high plateaus, and rolling uplands. This collision also crushed and folded sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic matter, organic particles at Earth#Surface, Earth's surface, followed by cementation (geology), cementation. Sedimentati ...

and igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main The three types of rocks, rock types, the others being Sedimentary rock, sedimentary and metamorphic rock, metamorphic. Igneous rock ...

s, creating a mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

called the Kootenay Fold Belt which existed in far eastern British Columbia.

After the sedimentary and igneous rocks were folded and crushed, it resulted in the creation of a new continental shelf and coastline. The Insular Plate continued to subduct under the new continental shelf and coastline about 130 million years ago during the mid

After the sedimentary and igneous rocks were folded and crushed, it resulted in the creation of a new continental shelf and coastline. The Insular Plate continued to subduct under the new continental shelf and coastline about 130 million years ago during the mid Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

period after the formation of the Intermontane Belt, supporting a new continental volcanic arc called the Omineca Arc. Magma rising from the Omineca Arc successfully connected the Intermontane Belt to the mainland of Western Canada, forming a chain of volcanoes in British Columbia that existed discontinuously for about 60 million years. The ocean lying offshore during this period is called the Bridge River Ocean. It was also during this period when another group of active volcanic islands existed along the newly built continental shelf and coastline. These volcanic islands, known as the Insular Islands

The Insular Islands were an extended chain of volcanic islands forming an arc in what is now the Pacific Ocean during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras. The islands formed by subduction and melting of the Farallon Plate along a fragment (or micropla ...

, were formed on the Insular Plate by subduction of the former Farallon Plate

The Farallon Plate was an ancient oceanic plate. It formed one of the three main plates of Panthalassa, alongside the Phoenix Plate and Izanagi Plate, which were connected by a triple junction. The Farallon Plate began subducting under the west c ...

to its west during the early Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

era. As the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

drifted west and the Insular Plate drifted east to the continental margin of Western Canada, the Bridge River Ocean began to close by ongoing subduction under the Bridge River Ocean. This subduction zone eventually jammed and shut down completely 115 million years ago, ending the Omineca Arc volcanism and the Insular Islands collided, forming the Insular Belt

The Insular Belt is a physical geography, physiogeological region on the north western North American coast. It consists of three major island groups and many smaller islands and stretches from southern British Columbia into Alaska and the Yukon. I ...

. Compression resulting from this collision crushed, fractured and folded rocks along the continental margin. The Insular Belt then welded onto the continental margin by magma that eventually cooled to create a large mass of igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main The three types of rocks, rock types, the others being Sedimentary rock, sedimentary and metamorphic rock, metamorphic. Igneous rock ...

, creating a new continental margin. This large mass of igneous rock is the largest granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

outcropping in North America.

The Farallon Plate continued to subduct under the new continental margin of Western Canada after the Insular Plate and Insular Islands collided with the former continental margin, supporting a new chain of volcanoes on the mainland of Western Canada called the

The Farallon Plate continued to subduct under the new continental margin of Western Canada after the Insular Plate and Insular Islands collided with the former continental margin, supporting a new chain of volcanoes on the mainland of Western Canada called the Coast Range Arc

The Coast Range Arc was a large volcanic arc system, extending from northern Washington through British Columbia and the Alaska Panhandle to southwestern Yukon. The Coast Range Arc lies along the western margin of the North American Plate in the P ...

about 100 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', the ...

epoch. Magma ascending from the Farallon Plate under the new continental margin burned their way upward through the newly accreted Insular Belt, injecting huge quantities of granite into older igneous rocks of the Insular Belt. At the surface, new volcanoes were built along the continental margin. The basement of this arc was likely Early Cretaceous and Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

age intrusions from the Insular Islands.

One of the major aspects that changed early during the Coast Range Arc was the status of the northern end of the Farallon Plate, a portion now known as the

One of the major aspects that changed early during the Coast Range Arc was the status of the northern end of the Farallon Plate, a portion now known as the Kula Plate

The Kula Plate was an oceanic tectonic plate under the northern Pacific Ocean south of the Near Islands segment of the Aleutian Islands. It has been subducted under the North American Plate at the Aleutian Trench, being replaced by the Pacific Pla ...

. About 85 million years ago, the Kula Plate broke off from the Farallon Plate to form an area of seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

called the Kula-Farallon Ridge

The Kula-Farallon Ridge was an ancient mid-ocean ridge that existed between the Kula and Farallon plates in the Pacific Ocean during the Jurassic period. There was a small piece of this ridge off the Pacific Northwest 43 million years ago. The r ...

. This change apparently had some important ramifications for regional geologic evolution. When this change was completed, Coast Range Arc volcanism returned and sections of the arc were uplifted considerably in latest Cretaceous time. This started a period of mountain building that affected much of western North America called the Laramide orogeny

The Laramide orogeny was a time period of mountain building in western North America, which started in the Late Cretaceous, 70 to 80 million years ago, and ended 35 to 55 million years ago. The exact duration and ages of beginning and end of the o ...

. In particular a large area of dextral transpression and southwest-directed thrust faulting was active from 75 to 66 million years ago. Much of the record of this deformation has been overridden by Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

age structures and the zone of Cretaceous dextral thrust faulting appears to have been widespread. It was also during this period when massive amounts of molten granite intruded highly deformed ocean rocks and assorted fragments from pre-existing island arcs, largely remnants of the Bridge River Ocean. This molten granite burned the old oceanic sediments into a glittering medium-grade metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock (protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, causin ...

called schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes o ...

. The older intrusions of the Coast Range Arc were then deformed under the heat and pressure of later intrusions, turning them into layered metamorphic rock known as gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures an ...

. In some places, mixtures of older intrusive rocks and the original oceanic rocks have been distorted and warped under intense heat, weight and stress to create unusual swirled patterns known as migmatite

Migmatite is a composite rock found in medium and high-grade metamorphic environments, commonly within Precambrian cratonic blocks. It consists of two or more constituents often layered repetitively: one layer is an older metamorphic rock tha ...

, appearing to have been nearly melted in the procedure.

Volcanism began to decline along the length of the arc about 60 million years ago during the Albian

The Albian is both an age of the geologic timescale and a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Early/Lower Cretaceous Epoch/Series. Its approximate time range is 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma to 100.5 ± 0.9 M ...

and Aptian

The Aptian is an age in the geologic timescale or a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early or Lower Cretaceous Epoch or Series and encompasses the time from 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma to 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma (million years ago), a ...

faunal stage

In chronostratigraphy, a stage is a succession of rock strata laid down in a single age on the geologic timescale, which usually represents millions of years of deposition. A given stage of rock and the corresponding age of time will by conventi ...

s of the Cretaceous period. This resulted from the changing geometry of the Kula Plate, which progressively developed a more northerly movement along the mainland of Western Canada. Instead of subducting beneath Western Canada, the Kula Plate began subducting underneath southwestern Yukon and Alaska during the early Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

period. Volcanism along the entire length of the Coast Range Arc shut down about 50 million years ago and many of the volcanoes have disappeared from erosion. What remains of the Coast Range Arc to this day are outcrops of granite when magma intruded and cooled at depth beneath the volcanoes, forming the Coast Mountains

The Coast Mountains (french: La chaîne Côtière) are a major mountain range in the Pacific Coast Ranges of western North America, extending from southwestern Yukon through the Alaska Panhandle and virtually all of the Coast of British Columbia ...

. During construction of intrusions 70 and 57 million years ago, the northern motion of the Kula Plate might have been between and per year. However, other geologic studies determined the Kula Plate moved at a rate as fast as per year.

Cascadia subduction zone complexes

As the last of the Kula Plate decayed and the Farallon Plate advanced back into this area from the south, it once again started to subduct under the continental margin of Western Canada 37 million years ago, supporting a chain of volcanoes called the

As the last of the Kula Plate decayed and the Farallon Plate advanced back into this area from the south, it once again started to subduct under the continental margin of Western Canada 37 million years ago, supporting a chain of volcanoes called the Cascade Volcanic Arc

The Cascade Volcanoes (also known as the Cascade Volcanic Arc or the Cascade Arc) are a number of volcanoes in a volcanic arc in western North America, extending from southwestern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern Califo ...

. At least four volcanic formations along the British Columbia Coast

, settlement_type = Region of British Columbia

, image_skyline =

, nickname = "The Coast"

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = British ...

are associated with Cascadia subduction zone volcanism. The oldest is the eroded 18-million-year-old Pemberton Volcanic Belt

The Pemberton Volcanic Belt is an eroded Oligocene-Miocene volcanic belt at a low angle near the Mount Meager massif, British Columbia, Canada. The Garibaldi and Pemberton volcanic belts appear to merge into a single belt, although the Pemberton ...

which extends west-northwest from south-central British Columbia to Haida Gwaii

Haida Gwaii (; hai, X̱aaydag̱a Gwaay.yaay / , literally "Islands of the Haida people") is an archipelago located between off the northern Pacific coast of Canada. The islands are separated from the mainland to the east by the shallow Hecat ...

in the northeast where it lies west of mainland British Columbia. In the south it is defined by a group of epizonal intrusions and a few erosional remnants of eruptive rock. Farther north in the large Ha-Iltzuk and Waddington icefields, it includes two large dissected calderas called Silverthrone Caldera

The Silverthrone Caldera is a potentially active caldera complex in southwestern British Columbia, Canada, located over northwest of the city of Vancouver and about west of Mount Waddington in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains. The cald ...

and Franklin Glacier Complex

The Franklin Glacier Complex is a deeply eroded volcano in the Waddington Range of southwestern British Columbia, Canada. Located about northeast of Kingcome, this sketchily known complex resides at Franklin Glacier near Mount Waddington. It i ...

while Haida Gwaii to the northeast contains a volcanic formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

ranging in age from Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

to Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Masset Formation

The Masset Formation is a volcanic formation on Graham Island of Haida Gwaii in British Columbia, Canada. It consists of calc-alkaline volcanic rocks related to subduction of the pre-existing Farallon Plate. The Masset Formation is part of the P ...

. Although widely separated from each other, all Pemberton Belt rocks are of similar age and have similar magma compositions. Therefore, these magmatic rocks are believed to be products of arc volcanism related to subduction of the Farallon Plate. By late Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Nootka Fault

The Nootka Fault is an active transform fault running southwest from Nootka Island, near Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada.

Geology

The Nootka Fault lies between the Explorer Plate in the north and Juan de Fuca Plate in south. These a ...

. This rupture created the two small Juan de Fuca

Juan de Fuca (10 June 1536, Cefalonia 23 July 1602, Cefalonia)Greek Consulate of Vancouver,Greek Pioneers: Juan de Fuca. was a Greeks, Greek maritime pilot, pilot who served Philip II of Spain, PhilipII of Spanish Empire, Spain. He is best know ...

and Explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

plates that lie off the west coast of Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are o ...

.

The four-million-year-old

The four-million-year-old Garibaldi Volcanic Belt

The Garibaldi Volcanic Belt is a northwest–southeast trending volcanic chain in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains that extends from Watts Point in the south to the Ha-Iltzuk Icefield in the north. This chain of volcanoes is located in ...

, a north-south trending zone of volcanoes and volcanic rock in the southern Coast Mountains

The Coast Mountains (french: La chaîne Côtière) are a major mountain range in the Pacific Coast Ranges of western North America, extending from southwestern Yukon through the Alaska Panhandle and virtually all of the Coast of British Columbia ...

of southwestern British Columbia, can be grouped into at least three enechelon segments, referred to as the northern, central, and southern segments. The northern segment overlaps the older Pemberton Volcanic Belt at a low angle near the Mount Meager massif

The Mount Meager massif is a group of volcanic peaks in the of the Coast Mountains in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. Part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc of western North America, it is located north of Vancouver at the northern end of the ...

where Garibaldi Belt lavas rest on uplifted and deeply eroded remnants of Pemberton Belt subvolcanic A subvolcanic rock, also known as a hypabyssal rock, is an intrusive igneous rock that is emplaced at depths less than within the crust, and has intermediate grain size and often porphyritic texture between that of volcanic rocks and plutonic r ...

intrusions and combines to form a single belt. A few isolated volcanoes northwest of the Mount Meager massif, such as Silverthrone Caldera and Franklin Glacier Complex, are also grouped as part of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt. However, their tectonic origins are largely unexplained and are a matter of going research. When the Farallon Plate ruptured to create the Nootka Fault between five and seven million years ago, there were some apparent changes along the Cascadia subduction zone. At issue is the current plate configuration and rate of subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

but based on rock composition is for Silverthrone Caldera and Franklin Glacier Complex to be subduction related. The roughly circular, wide, deeply dissected Silverthrone Caldera in the northern segment of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, was formed one million years ago during the Early Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, being the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently estimated to span the time ...

period. The bulk of the volcano was erupted 0.4 million years ago, but younger phases, consisting of lava flows and subsidiary volcanoes with compositions of andesite and basaltic andesite

Basaltic andesite is a volcanic rock that is intermediate in composition between basalt and andesite. It is composed predominantly of augite and plagioclase. Basaltic andesite can be found in volcanoes around the world, including in Central Ameri ...

are also present. Mount Silverthrone

Mount is often used as part of the name of specific mountains, e.g. Mount Everest.

Mount or Mounts may also refer to:

Places

* Mount, Cornwall, a village in Warleggan parish, England

* Mount, Perranzabuloe, a hamlet in Perranzabuloe parish, C ...

, an eroded lava dome

In volcanology, a lava dome is a circular mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. Dome-building eruptions are common, particularly in convergent plate boundary settings. Around 6% of eruptions on ...

on the northeast edge of Silverthrone Caldera, was episodically active during both Pemberton and Garibaldi stages of volcanism. The eroded Franklin Glacier Complex just to the southeast consists of dacite and andesite rocks that range in age from 3.9 to 2.2 million years old. Southeast of Franklin Glacier Complex, the Bridge River Cones comprise remnants of both andesitic and alkali basalt cones and lava flows. These range in age from about one million years old to 0.5 million years old and commonly display ice-contact features related to subglacial eruption

Subglacial eruptions, those of ice-covered volcanoes, result in the interaction of magma with ice and snow, leading to meltwater formation, jökulhlaups, and lahars. Flooding associated with meltwater is a significant hazard in some volcan ...

s. The Mount Meager massif, the most persistent volcano in the northern portion of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt, is a complex of at least four overlapping stratovolcanoes made of dacite and rhyodacite that become progressively younger from south to north, ranging in age from two million to 2,490 years old. The central segment of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt is defined by a group of eight volcanoes on a ridge of highland east of the Squamish River

The Squamish River is a short but very large river in the Canadian province of British Columbia. Its drainage basin is in size. The total length of the Squamish River is approximately .

Course

The Squamish River drains a complex of basins in the ...

, and by remnants of basaltic lava flows preserved in the adjacent Squamish valley. Mount Cayley

Mount Cayley is an eroded but potentially active stratovolcano in the Pacific Ranges of southwestern British Columbia, Canada. Located north of Squamish and west of Whistler, the volcano resides on the edge of the Powder Mountain Icefield. ...

, the largest and most persistent volcano, is a deeply eroded stratovolcano comprising a lava dome complex made of dacite and minor rhyodacite ranging in age from 3.8 to 0.31 million years old. Mount Fee

Mount Fee is a volcanic peak in the Pacific Ranges of the Coast Mountains in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. It is located south of Callaghan Lake and west of the resort town of Whistler. With a summit elevation of and a topographic ...

, a narrow volcanic plug

A volcanic plug, also called a volcanic neck or lava neck, is a volcanic object created when magma hardens within a vent on an active volcano. When present, a plug can cause an extreme build-up of high gas pressure if rising volatile-charged mag ...

made of rhyodacite about long and wide, rises above the highland ridge. Complete denudation of the central spine as well as the absence of till under lava flows from Mount Fee suggest a preglacial age. The other volcanoes of the central Garibaldi Belt, including Ember Ridge

Ember Ridge is a volcanic mountain ridge associated with the Mount Cayley volcanic field in British Columbia, Canada. Ember Ridge is made of a series of steep-sided domes of glassy, complexly jointed, hornblende-phyric basalt with the most recent e ...