Timeline of chemistry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This timeline of chemistry lists important works, discoveries, ideas, inventions, and experiments that significantly changed humanity's understanding of the modern science known as chemistry, defined as the scientific study of the composition of matter and of its interactions.

Known as "

This timeline of chemistry lists important works, discoveries, ideas, inventions, and experiments that significantly changed humanity's understanding of the modern science known as chemistry, defined as the scientific study of the composition of matter and of its interactions.

Known as "

Prior to the acceptance of the

Prior to the acceptance of the

Vitriol in the history of Chemistry

Charles University ;c. 1267: Roger Bacon publishes ''Opus Maius'', which among other things, proposes an early form of the scientific method, and contains results of his experiments with

;1661:

;1661: ;1757:

;1757: ;1778:

;1778:

This timeline of chemistry lists important works, discoveries, ideas, inventions, and experiments that significantly changed humanity's understanding of the modern science known as chemistry, defined as the scientific study of the composition of matter and of its interactions.

Known as "

This timeline of chemistry lists important works, discoveries, ideas, inventions, and experiments that significantly changed humanity's understanding of the modern science known as chemistry, defined as the scientific study of the composition of matter and of its interactions.

Known as "the central science

Chemistry is often called the central science because of its role in connecting the physical sciences, which include chemistry, with the life sciences and applied sciences such as medicine and engineering. The nature of this relationship is one o ...

", the study of chemistry is strongly influenced by, and exerts a strong influence on, many other scientific and technological fields. Many historical developments that are considered to have had a significant impact upon our modern understanding of chemistry are also considered to have been key discoveries in such fields as physics, biology, astronomy, geology, and materials science.

Pre-17th century

Prior to the acceptance of the

Prior to the acceptance of the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

and its application to the field of chemistry, it is somewhat controversial to consider many of the people listed below as "chemists" in the modern sense of the word. However, the ideas of certain great thinkers, either for their prescience, or for their wide and long-term acceptance, bear listing here.

;c. 450 BC: Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

asserts that all things are composed of four primal roots (later to be renamed ''stoicheia'' or elements): earth, air, fire, and water, whereby two active and opposing cosmic forces, love and strife, act upon these elements, combining and separating them into infinitely varied forms.

;c. 440 BC: Leucippus

Leucippus (; el, Λεύκιππος, ''Leúkippos''; fl. 5th century BCE) is a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who has been credited as the first philosopher to develop a theory of atomism.

Leucippus' reputation, even in antiquity, was obscured ...

and Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

propose the idea of the atom, an indivisible particle that all matter is made of. This idea is largely rejected by natural philosophers in favor of the Aristotlean view (see below).

;c. 360 BC: Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

coins term ‘ elements’ (''stoicheia'') and in his dialogue Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

*Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Greek ...

, which includes a discussion of the composition of inorganic and organic bodies and is a rudimentary treatise on chemistry, assumes that the minute particle of each element had a special geometric shape: tetrahedron

In geometry, a tetrahedron (plural: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular faces, six straight edges, and four vertex corners. The tetrahedron is the simplest of all th ...

(fire), octahedron

In geometry, an octahedron (plural: octahedra, octahedrons) is a polyhedron with eight faces. The term is most commonly used to refer to the regular octahedron, a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at ea ...

(air), icosahedron (water), and cube (earth).

;c. 350 BC: Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

, expanding on Empedocles, proposes idea of a substance as a combination of ''matter'' and ''form''. Describes theory of the Five Elements, fire, water, earth, air, and aether. This theory is largely accepted throughout the western world for over 1000 years.

; c. 50 BC: Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into En ...

publishes '' De Rerum Natura'', a poetic description of the ideas of atomism

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms ...

.

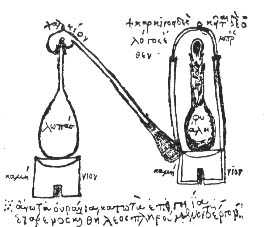

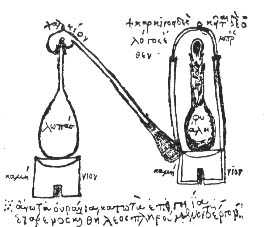

;c. 300: Zosimos of Panopolis

Zosimos of Panopolis ( el, Ζώσιμος ὁ Πανοπολίτης; also known by the Latin name Zosimus Alchemista, i.e. "Zosimus the Alchemist") was a Greco-Egyptian alchemist and Gnostic mystic who lived at the end of the 3rd and beginning ...

writes some of the oldest known books on alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

, which he defines as the study of the composition of waters, movement, growth, embodying and disembodying, drawing the spirits from bodies and bonding the spirits within bodies.

;c. 800: ''The Secret of Creation'' (Arabic: ''Sirr al-khalīqa''), an anonymous encyclopedic work on natural philosophy falsely attributed to Apollonius of Tyana

Apollonius of Tyana ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Τυανεύς; c. 3 BC – c. 97 AD) was a Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from the town of Tyana in the Roman province of Cappadocia in Anatolia. He is the subject of '' ...

, records the earliest known version of the long-held theory that all metals are composed of various proportions of sulfur and mercury. This same work also contains the earliest known version of the '' Emerald Tablet'', a compact and cryptic Hermetic

Hermetic or related forms may refer to:

* of or related to the ancient Greek Olympian god Hermes

* of or related to Hermes Trismegistus, a legendary Hellenistic figure based on the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth

** , the ancient and m ...

text which was still commented upon by Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

.

;c. 850–900: Arabic works attributed to Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Latin: Geber) introduce a systematic classification of chemical substances, and provide instructions for deriving an inorganic compound (sal ammoniac

Salammoniac, also sal ammoniac or salmiac, is a rare naturally occurring mineral composed of ammonium chloride, NH4Cl. It forms colorless, white, or yellow-brown crystals in the isometric-hexoctahedral class. It has very poor cleavage and is ...

or ammonium chloride) from organic substances (such as plants, blood, and hair) by chemical means.

;c. 900: Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (Latin: Rhazes), a Persian alchemist, conducts experiments with the distillation of sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride), vitriols (hydrated sulfates

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many a ...

of various metals), and other salts

In chemistry, a salt is a chemical compound consisting of an ionic assembly of positively charged cations and negatively charged anions, which results in a compound with no net electric charge. A common example is table salt, with positively c ...

, representing the first step in a long process that would eventually lead to the thirteenth-century discovery of the mineral acids

A mineral acid (or inorganic acid) is an acid derived from one or more inorganic compounds, as opposed to organic acids which are acidic, organic compounds. All mineral acids form hydrogen ions and the conjugate base when dissolved in water.

Ch ...

.

;c. 1000: Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

and Avicenna, both Persian philosophers, deny the possibility of the transmutation of metals.

;c. 1100–1200: Recipes for the production of ''aqua ardens'' ("burning water", i.e., ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a ...

) by distilling wine with common salt start to appear in a number of Latin alchemical works.

;c. 1220: Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste, ', ', or ') or the gallicised Robert Grosstête ( ; la, Robertus Grossetesta or '). Also known as Robert of Lincoln ( la, Robertus Lincolniensis, ', &c.) or Rupert of Lincoln ( la, Rubertus Lincolniensis, &c.). ( ; la, Rob ...

publishes several Aristotelian commentaries where he lays out an early framework for the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

.

;c 1250: The works of Taddeo Alderotti

Taddeo Alderotti (Latin: Thaddaeus Alderottus, French : Thaddée de Florence), born in Florence between 1206 and 1215, died in 1295, was an Italian doctor and professor of medicine at the University of Bologna, who made important contributions t ...

(1223–1296) describe a method for concentrating ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a ...

involving repeated fractional distillation through a water-cooled still, by which an ethanol purity of 90% could be obtained.

;c 1260: St Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop. Later canonised as a Catholic saint, he was known during his li ...

discovers arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

and silver nitrate

Silver nitrate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula . It is a versatile precursor to many other silver compounds, such as those used in photography. It is far less sensitive to light than the halides. It was once called ''lunar causti ...

. He also made one of the first references to sulfuric acid.Vladimir Karpenko, John A. Norris(2001)Vitriol in the history of Chemistry

Charles University ;c. 1267: Roger Bacon publishes ''Opus Maius'', which among other things, proposes an early form of the scientific method, and contains results of his experiments with

gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

.

;c. 1310: Pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber (or "Latin pseudo-Geber") is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attributed to Jabir ...

, an anonymous alchemist who wrote under the name of Geber (i.e., Jābir ibn Hayyān, see above), publishes the . This work contains experimental demonstrations of the corpuscular nature of matter that would still be used by seventeenth-century chemists such as Daniel Sennert

Daniel Sennert (25 November 1572 – 21 July 1637) was a renowned German physician and a prolific academic writer, especially in the field of alchemy or chemistry. He held the position of professor of medicine at the University of Wittenberg for ma ...

. Pseudo-Geber is one of the first alchemists to describe mineral acids

A mineral acid (or inorganic acid) is an acid derived from one or more inorganic compounds, as opposed to organic acids which are acidic, organic compounds. All mineral acids form hydrogen ions and the conjugate base when dissolved in water.

Ch ...

such as or 'strong water' (nitric acid, capable of dissolving silver) and or 'royal water' (a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, capable of dissolving gold and platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

).

;c. 1530: Paracelsus develops the study of iatrochemistry

Iatrochemistry (; also known as chemiatria or chemical medicine) is a branch of both chemistry and medicine. Having its roots in alchemy, iatrochemistry seeks to provide chemical solutions to diseases and medical ailments.

This area of scien ...

, a subdiscipline of alchemy dedicated to extending life, thus being the roots of the modern pharmaceutical industry

The pharmaceutical industry discovers, develops, produces, and markets drugs or pharmaceutical drugs for use as medications to be administered to patients (or self-administered), with the aim to cure them, vaccinate them, or alleviate symptoms. ...

. It is also claimed that he is the first to use the word "chemistry".

;1597: Andreas Libavius

Andreas Libavius or Andrew Libavius was born in Halle, Germany c. 1550 and died in July 1616. Libavius was a renaissance man who spent time as a professor at the University of Jena teaching history and poetry. After which he became a physician a ...

publishes ''Alchemia'', a prototype chemistry textbook.

17th and 18th centuries

;1605:Sir Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both n ...

publishes ''The Proficience and Advancement of Learning'', which contains a description of what would later be known as the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific ...

.

;1605:Michal Sedziwój

Michael Sendivogius (; pl, Michał Sędziwój; 2 February 1566 – 1636) was a Polish alchemist, philosopher, and medical doctor. A pioneer of chemistry, he developed ways of purification and creation of various acids, metals and other ch ...

publishes the alchemical treatise ''A New Light of Alchemy'' which proposed the existence of the "food of life" within air, much later recognized as oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

.

;1615:Jean Beguin Jean Beguin (1550–1620) was an iatrochemist noted for his 1610 ''Tyrocinium Chymicum'' (Begin Chemistry)Digital edition, which many consider to be one of the first chemistry textbooks. In the 1615 edition of his textbook, Beguin made the first-e ...

publishes the '' Tyrocinium Chymicum'', an early chemistry textbook, and in it draws the first-ever chemical equation

A chemical equation is the symbolic representation of a chemical reaction in the form of symbols and chemical formulas. The reactant entities are given on the left-hand side and the product entities on the right-hand side with a plus sign between ...

.

;1637:René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Ma ...

publishes ''Discours de la méthode

''Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences'' (french: Discours de la Méthode Pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences) is a philosophical and autobiographical ...

'', which contains an outline of the scientific method.

;1648:Posthumous publication of the book ''Ortus medicinae'' by Jan Baptist van Helmont

Jan Baptist van Helmont (; ; 12 January 1580 – 30 December 1644) was a chemist, physiologist, and physician from Brussels. He worked during the years just after Paracelsus and the rise of iatrochemistry, and is sometimes considered to b ...

, which is cited by some as a major transitional work between alchemy and chemistry, and as an important influence on Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

. The book contains the results of numerous experiments and establishes an early version of the law of conservation of mass.

;1661:

;1661:Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

publishes ''The Sceptical Chymist

''The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes'' is the title of a book by Robert Boyle, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the ''Sceptical Chymist'' presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of corp ...

'', a treatise on the distinction between chemistry and alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

. It contains some of the earliest modern ideas of atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, ...

s, molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

s, and chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the IUPAC nomenclature for organic transformations, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the pos ...

, and marks the beginning of the history of modern chemistry.

;1662:Robert Boyle proposes Boyle's law

Boyle's law, also referred to as the Boyle–Mariotte law, or Mariotte's law (especially in France), is an experimental gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume of a confined gas. Boyle's law has been stated as:

The ...

, an experimentally based description of the behavior of gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

es, specifically the relationship between pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and e ...

and volume

Volume is a measure of occupied three-dimensional space. It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial or US customary units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch). Th ...

.

;1735:Swedish chemist Georg Brandt

Georg Brandt (26 June 1694 – 29 April 1768) was a Swedish chemist and mineralogist who discovered cobalt (c. 1735). He was the first person to discover a metal unknown in ancient times. He is also known for exposing fraudulent alchemists operatin ...

analyzes a dark blue pigment found in copper ore. Brandt demonstrated that the pigment contained a new element, later named cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, p ...

.

;1754:Joseph Black

Joseph Black (16 April 1728 – 6 December 1799) was a Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of magnesium, latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was Professor of Anatomy and Chemistry at the University of Glas ...

isolates carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

, which he called "fixed air".

;1757:

;1757:Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt

Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt (24 July 1731 – 17 October 1799) was a French chemist who synthesised the first organometalic compound.

He obtained a red liquid by the reaction of potassium acetate with arsenic trioxide. This liquid is ...

, while investigating arsenic compounds, creates Cadet's fuming liquid

Cadet's fuming liquid was a red-brown oily liquid prepared in 1760 by the French chemist Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt (1731-1799) by the reaction of potassium acetate with arsenic trioxide. It consisted mostly of dicacodyl (((CH3)2As)2) an ...

, later discovered to be cacodyl oxide

Cacodyl oxide is a chemical compound of the formula CH3)2Assub>2O. This organoarsenic compound is primarily of historical significance since it is sometimes considered to be the first organometallic compound synthesized in relatively pure form. ...

, considered to be the first synthetic organometallic compound.

;1758:Joseph Black

Joseph Black (16 April 1728 – 6 December 1799) was a Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of magnesium, latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was Professor of Anatomy and Chemistry at the University of Glas ...

formulates the concept of latent heat

Latent heat (also known as latent energy or heat of transformation) is energy released or absorbed, by a body or a thermodynamic system, during a constant-temperature process — usually a first-order phase transition.

Latent heat can be underst ...

to explain the thermochemistry

Thermochemistry is the study of the heat energy which is associated with chemical reactions and/or phase changes such as melting and boiling. A reaction may release or absorb energy, and a phase change may do the same. Thermochemistry focuses on ...

of phase changes

In chemistry, thermodynamics, and other related fields, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic states of ...

.

;1766:Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English natural philosopher and scientist who was an important experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "infl ...

discovers hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

as a colorless, odourless gas that burns and can form an explosive mixture with air.

;1773–1774: Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified molybdenum, tungsten, barium, hyd ...

and Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

independently isolate oxygen, called by Priestley "dephlogisticated air" and Scheele "fire air".

;1778:

;1778:Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

CNRS (

;1787:Antoine Lavoisier publishes ''Méthode de nomenclature chimique'', the first modern system of chemical nomenclature.

;1787:

;1803: John Dalton proposes

;1803: John Dalton proposes  ;1825: Friedrich Wöhler and Justus von Liebig perform the first confirmed discovery and explanation of

;1825: Friedrich Wöhler and Justus von Liebig perform the first confirmed discovery and explanation of  ;1869: Dmitri Mendeleev publishes the first modern periodic table, with the 66 known elements organized by atomic weights. The strength of his table was its ability to accurately predict the properties of as-yet unknown elements.

;1873: Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel, working independently, develop a model of

;1869: Dmitri Mendeleev publishes the first modern periodic table, with the 66 known elements organized by atomic weights. The strength of his table was its ability to accurately predict the properties of as-yet unknown elements.

;1873: Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel, working independently, develop a model of

;1909:

;1909: ;1913:Niels Bohr introduces concepts of quantum mechanics to atomic structure by proposing what is now known as the Bohr model of the atom, where electrons exist only in strictly defined Atomic orbital, orbitals.

;1913:Henry Moseley, working from Van den Broek's earlier idea, introduces concept of atomic number to fix inadequacies of Mendeleev's periodic table, which had been based on atomic weight.

;1913:Frederick Soddy proposes the concept of isotopes, that elements with the same chemical properties may have differing atomic weights.

;1913:

;1913:Niels Bohr introduces concepts of quantum mechanics to atomic structure by proposing what is now known as the Bohr model of the atom, where electrons exist only in strictly defined Atomic orbital, orbitals.

;1913:Henry Moseley, working from Van den Broek's earlier idea, introduces concept of atomic number to fix inadequacies of Mendeleev's periodic table, which had been based on atomic weight.

;1913:Frederick Soddy proposes the concept of isotopes, that elements with the same chemical properties may have differing atomic weights.

;1913: ;1932:James Chadwick discovers the neutron.

;1932–1934:Linus Pauling and Robert Mulliken quantify electronegativity, devising the scales that now bear their names.

;1935:Wallace Carothers leads a team of chemists at DuPont who invent nylon, one of the most commercially successful synthetic polymers in history.

;1937:Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè perform the first confirmed synthesis of technetium, technetium-97, the first artificially produced element, filling a gap in the periodic table. Though disputed, the element may have been synthesized as early as 1925 by Walter Noddack and others.

;1937:Eugene Houdry develops a method of industrial scale catalytic cracking of petroleum, leading to the development of the first modern oil refinery.

;1937:Pyotr Kapitsa, John F. Allen (physicist), John Allen and Don Misener produce supercooled helium, helium-4, the first zero-viscosity superfluid, a substance that displays quantum mechanical properties on a macroscopic scale.

;1938:Otto Hahn discovers the process of nuclear fission in uranium and thorium.

;1939:Linus Pauling publishes ''The Nature of the Chemical Bond'', a compilation of a decades worth of work on chemical bonding. It is one of the most important modern chemical texts. It explains orbital hybridization, hybridization theory, covalent bonding and ionic bonding as explained through electronegativity, and resonance (chemistry), resonance as a means to explain, among other things, the structure of benzene.

;1940:Edwin McMillan and Philip H. Abelson identify neptunium, the lightest and first synthesized transuranium element, found in the products of uranium Nuclear fission, fission. McMillan would found a lab at University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley that would be involved in the discovery of many new elements and isotopes.

;1941:Glenn T. Seaborg takes over McMillan's work creating new atomic nuclei. Pioneers method of neutron capture and later through other nuclear reactions. Would become the principal or co-discoverer of nine new chemical elements, and dozens of new isotopes of existing elements.

;1944

:Robert Burns Woodward and William von Eggers Doering successfully synthesized of

;1932:James Chadwick discovers the neutron.

;1932–1934:Linus Pauling and Robert Mulliken quantify electronegativity, devising the scales that now bear their names.

;1935:Wallace Carothers leads a team of chemists at DuPont who invent nylon, one of the most commercially successful synthetic polymers in history.

;1937:Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè perform the first confirmed synthesis of technetium, technetium-97, the first artificially produced element, filling a gap in the periodic table. Though disputed, the element may have been synthesized as early as 1925 by Walter Noddack and others.

;1937:Eugene Houdry develops a method of industrial scale catalytic cracking of petroleum, leading to the development of the first modern oil refinery.

;1937:Pyotr Kapitsa, John F. Allen (physicist), John Allen and Don Misener produce supercooled helium, helium-4, the first zero-viscosity superfluid, a substance that displays quantum mechanical properties on a macroscopic scale.

;1938:Otto Hahn discovers the process of nuclear fission in uranium and thorium.

;1939:Linus Pauling publishes ''The Nature of the Chemical Bond'', a compilation of a decades worth of work on chemical bonding. It is one of the most important modern chemical texts. It explains orbital hybridization, hybridization theory, covalent bonding and ionic bonding as explained through electronegativity, and resonance (chemistry), resonance as a means to explain, among other things, the structure of benzene.

;1940:Edwin McMillan and Philip H. Abelson identify neptunium, the lightest and first synthesized transuranium element, found in the products of uranium Nuclear fission, fission. McMillan would found a lab at University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley that would be involved in the discovery of many new elements and isotopes.

;1941:Glenn T. Seaborg takes over McMillan's work creating new atomic nuclei. Pioneers method of neutron capture and later through other nuclear reactions. Would become the principal or co-discoverer of nine new chemical elements, and dozens of new isotopes of existing elements.

;1944

:Robert Burns Woodward and William von Eggers Doering successfully synthesized of  ;1985:Harold Kroto, Robert Curl and Richard Smalley discover fullerenes, a class of large carbon molecules superficially resembling the geodesic dome designed by architect R. Buckminster Fuller.

;1991:Sumio Iijima uses electron microscopy to discover a type of cylindrical fullerene known as a carbon nanotube, though earlier work had been done in the field as early as 1951. This material is an important component in the field of nanotechnology.

;1994:First Holton Taxol total synthesis, total synthesis of Taxol by Robert A. Holton and his group.

;1995:Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman produce the first Bose–Einstein condensate, a substance that displays quantum mechanical properties on the macroscopic scale.

;1985:Harold Kroto, Robert Curl and Richard Smalley discover fullerenes, a class of large carbon molecules superficially resembling the geodesic dome designed by architect R. Buckminster Fuller.

;1991:Sumio Iijima uses electron microscopy to discover a type of cylindrical fullerene known as a carbon nanotube, though earlier work had been done in the field as early as 1951. This material is an important component in the field of nanotechnology.

;1994:First Holton Taxol total synthesis, total synthesis of Taxol by Robert A. Holton and his group.

;1995:Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman produce the first Bose–Einstein condensate, a substance that displays quantum mechanical properties on the macroscopic scale.

''Physical chemistry from Ostwald to Pauling : the making of a science in America''

Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1990.

Eric Weisstein's World of Scientific Biographylist of all Nobel Prize laureates

{{DEFAULTSORT:Timeline Of Chemistry Chemistry timelines, History of chemistry Lists of inventions or discoveries, Chemistry, timeline of

Jacques Charles

Jacques Alexandre César Charles (November 12, 1746 – April 7, 1823) was a French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist.

Charles wrote almost nothing about mathematics, and most of what has been credited to him was due to mistaking ...

proposes Charles's law

Charles's law (also known as the law of volumes) is an experimental gas law that describes how gases tend to expand when heated. A modern statement of Charles's law is:

When the pressure on a sample of a dry gas is held constant, the Kelvin t ...

, a corollary of Boyle's law, describes relationship between temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various Conversion of units of temperature, temp ...

and volume of a gas.

;1789:Antoine Lavoisier publishes ''Traité Élémentaire de Chimie

''Traité élémentaire de chimie'' (''Elementary Treatise on Chemistry'') is a textbook written by Antoine Lavoisier published in 1789 and translated into English by Robert Kerr in 1790 under the title ''Elements of Chemistry in a New Systemati ...

'', the first modern chemistry textbook. It is a complete survey of (at that time) modern chemistry, including the first concise definition of the law of conservation of mass, and thus also represents the founding of the discipline of stoichiometry or quantitative chemical analysis.

;1797:Joseph Proust

Joseph Louis Proust (26 September 1754 – 5 July 1826) was a French chemist. He was best known for his discovery of the law of definite proportions in 1794, stating that chemical compounds always combine in constant proportions.

Life

Joseph L. ...

proposes the law of definite proportions

In chemistry, the law of definite proportions, sometimes called Proust's law, or law of constant composition states that a given

chemical compound always contains its component elements in fixed ratio (by mass) and does not depend on its source an ...

, which states that elements always combine in small, whole number ratios to form compounds.

;1800: Alessandro Volta devises the first chemical battery, thereby founding the discipline of electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outco ...

.

19th century

;1803: John Dalton proposes

;1803: John Dalton proposes Dalton's law

Dalton's law (also called Dalton's law of partial pressures) states that in a mixture of non-reacting gases, the total pressure exerted is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the individual gases. This empirical law was observed by Joh ...

, which describes relationship between the components in a mixture of gases and the relative pressure each contributes to that of the overall mixture.

;1805:Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (, , ; 6 December 1778 – 9 May 1850) was a French chemist and physicist. He is known mostly for his discovery that water is made of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen (with Alexander von Humboldt), for two laws ...

discovers that water is composed of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen by volume.

;1808:Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac collects and discovers several chemical and physical properties of air and of other gases, including experimental proofs of Boyle's and Charles's law

Charles's law (also known as the law of volumes) is an experimental gas law that describes how gases tend to expand when heated. A modern statement of Charles's law is:

When the pressure on a sample of a dry gas is held constant, the Kelvin t ...

s, and of relationships between density and composition of gases.

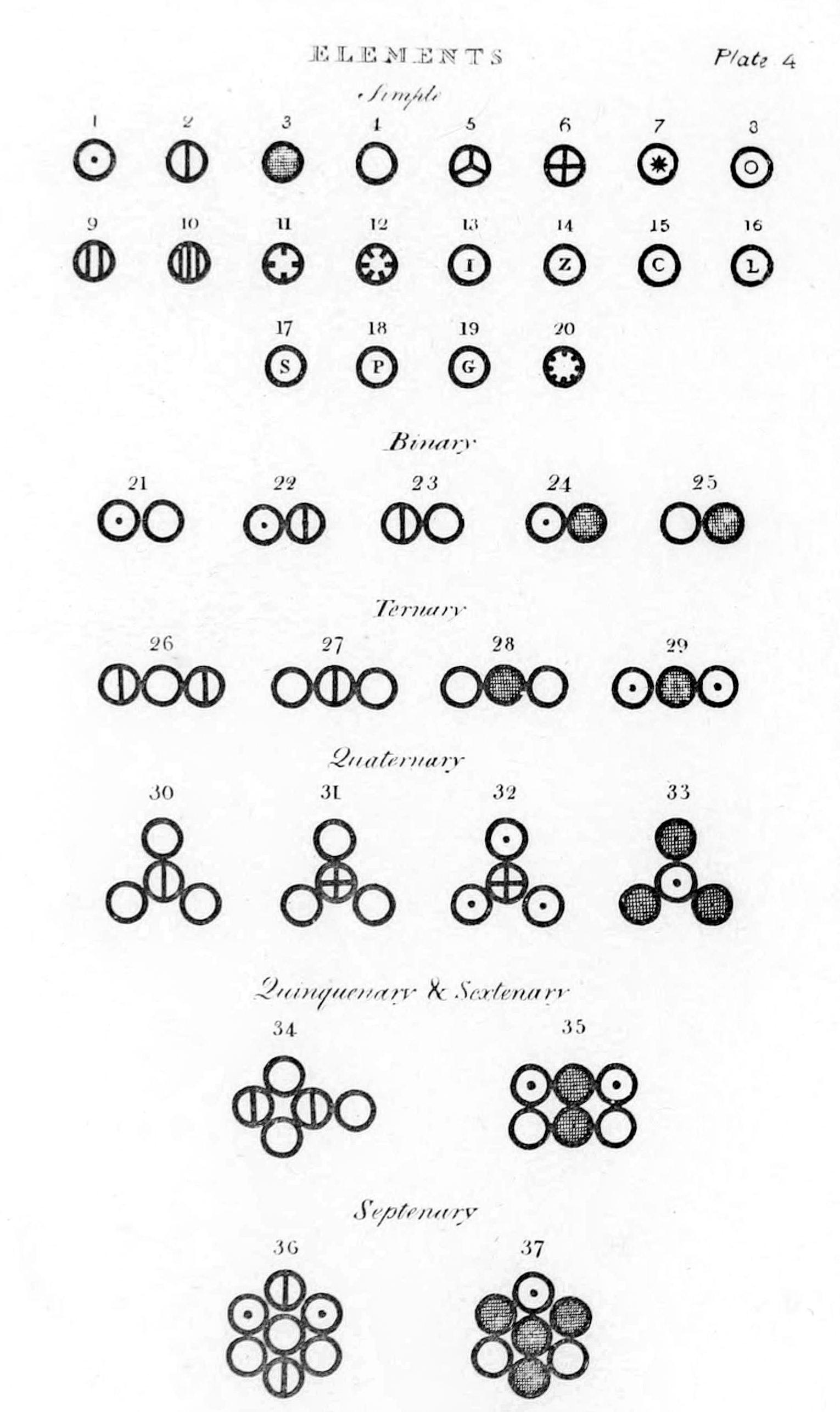

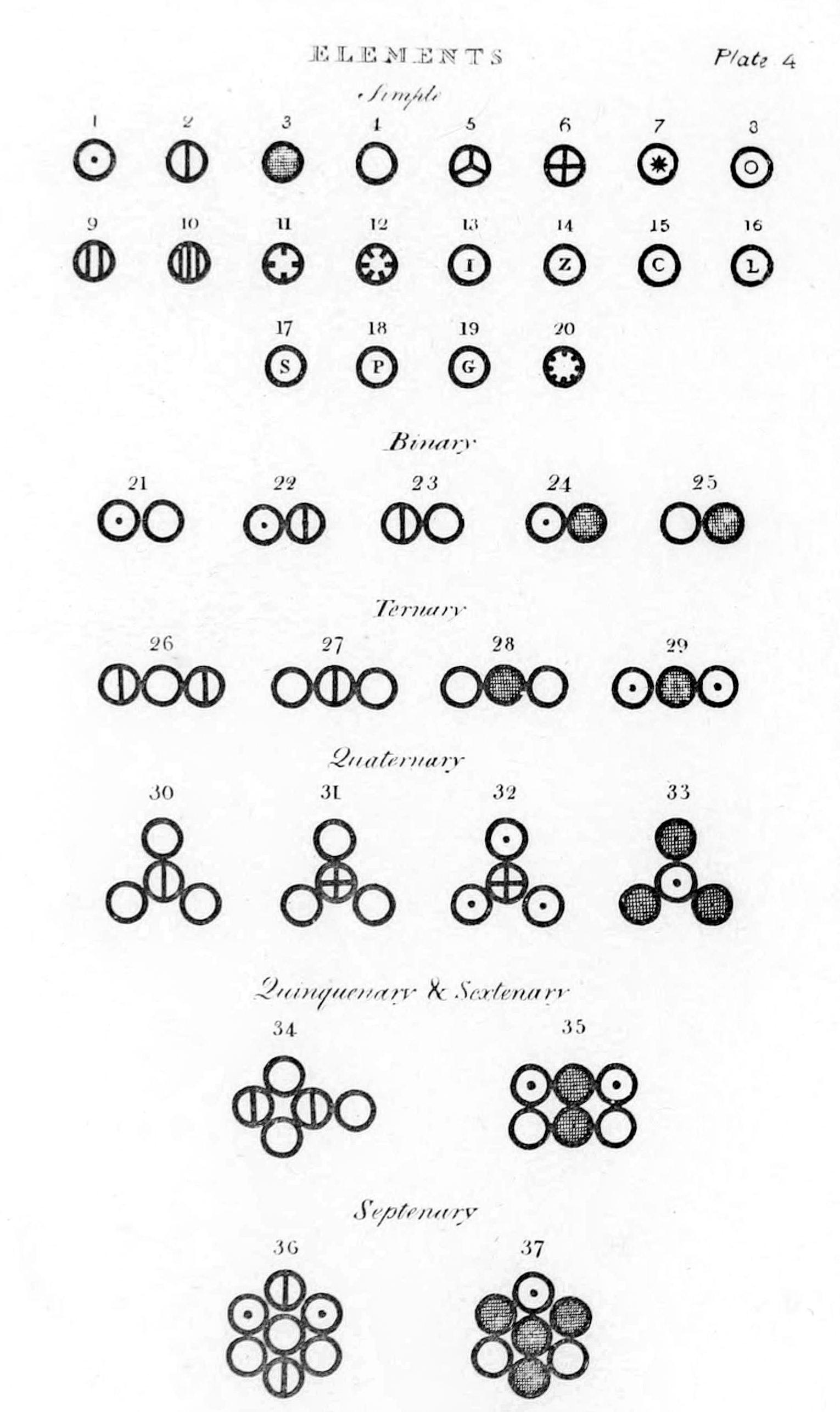

;1808:John Dalton publishes ''New System of Chemical Philosophy'', which contains first modern scientific description of the atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter ...

, and clear description of the law of multiple proportions

In chemistry, the law of multiple proportions states that if two elements form more than one compound, then the ratios of the masses of the second element which combine with a fixed mass of the first element will always be ratios of small whole ...

.

;1808:Jöns Jakob Berzelius

Jöns is a Swedish given name and a surname.

Notable people with the given name include:

* Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779–1848), Swedish chemist

* Jöns Budde (1435–1495), Franciscan friar from the Brigittine monastery in NaantaliVallis Grati ...

publishes ''Lärbok i Kemien'' in which he proposes modern chemical symbols

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wit ...

and notation, and of the concept of relative atomic weight

Relative atomic mass (symbol: ''A''; sometimes abbreviated RAM or r.a.m.), also known by the deprecated synonym atomic weight, is a dimensionless physical quantity defined as the ratio of the average mass of atoms of a chemical element in a giv ...

.

;1811:Amedeo Avogadro

Lorenzo Romano Amedeo Carlo Avogadro, Count of Quaregna and Cerreto (, also , ; 9 August 17769 July 1856) was an Italian scientist, most noted for his contribution to molecular theory now known as Avogadro's law, which states that equal volume ...

proposes Avogadro's law

Avogadro's law (sometimes referred to as Avogadro's hypothesis or Avogadro's principle) or Avogadro-Ampère's hypothesis is an experimental gas law relating the volume of a gas to the amount of substance of gas present. The law is a specific c ...

, that equal volumes of gases under constant temperature and pressure contain equal number of molecules.

isomers

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

...

, earlier named by Berzelius. Working with cyanic acid and fulminic acid, they correctly deduce that isomerism was caused by differing arrangements of atoms within a molecular structure.

;1827:William Prout classifies biomolecules into their modern groupings: carbohydrates, proteins and lipids

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include ...

.

;1828:Friedrich Wöhler synthesizes urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

, thereby establishing that organic compounds could be produced from inorganic starting materials, disproving the theory of vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

.

;1832:Friedrich Wöhler and Justus von Liebig discover and explain functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is a substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the re ...

s and radicals in relation to organic chemistry.

;1840: Germain Hess proposes Hess's law, an early statement of the law of conservation of energy

In physics and chemistry, the law of conservation of energy states that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant; it is said to be ''conserved'' over time. This law, first proposed and tested by Émilie du Châtelet, means that ...

, which establishes that energy changes in a chemical process depend only on the states of the starting and product materials and not on the specific pathway taken between the two states.

;1847:Hermann Kolbe

Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe (27 September 1818 – 25 November 1884) was a major contributor to the birth of modern organic chemistry. He was a professor at Marburg and Leipzig. Kolbe was the first to apply the term synthesis in a chemical cont ...

obtains acetic acid from completely inorganic sources, further disproving vitalism.

;1848:Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, (26 June 182417 December 1907) was a British mathematician, mathematical physicist and engineer born in Belfast. Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow for 53 years, he did important ...

establishes concept of absolute zero, the temperature at which all molecular motion ceases.

;1849: Louis Pasteur discovers that the racemic

In chemistry, a racemic mixture, or racemate (), is one that has equal amounts of left- and right-handed enantiomers of a chiral molecule or salt. Racemic mixtures are rare in nature, but many compounds are produced industrially as racemates. ...

form of tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white, crystalline organic acid that occurs naturally in many fruits, most notably in grapes, but also in bananas, tamarinds, and citrus. Its salt, potassium bitartrate, commonly known as cream of tartar, develops naturally ...

is a mixture of the levorotatory and dextrotatory forms, thus clarifying the nature of optical rotation and advancing the field of stereochemistry.

;1852: August Beer proposes Beer's law, which explains the relationship between the composition of a mixture and the amount of light it will absorb. Based partly on earlier work by Pierre Bouguer and Johann Heinrich Lambert

Johann Heinrich Lambert (, ''Jean-Henri Lambert'' in French; 26 or 28 August 1728 – 25 September 1777) was a polymath from the Republic of Mulhouse, generally referred to as either Swiss or French, who made important contributions to the subject ...

, it establishes the analytical technique known as spectrophotometry

Spectrophotometry is a branch of electromagnetic spectroscopy concerned with the quantitative measurement of the reflection or transmission properties of a material as a function of wavelength. Spectrophotometry uses photometers, known as sp ...

.

;1855:Benjamin Silliman, Jr.

Benjamin Silliman Jr. (December 4, 1816 – January 14, 1885) was a professor of chemistry at Yale University and instrumental in developing the oil industry.

His father Benjamin Silliman Sr., also a famous Yale chemist, developed the process ...

pioneers methods of petroleum cracking

In petrochemistry, petroleum geology and organic chemistry, cracking is the process whereby complex organic compound, organic molecules such as kerogens or long-chain hydrocarbons are broken down into simpler molecules such as light hydrocarbons, b ...

, which makes the entire modern petrochemical industry

The petrochemical industry is concerned with the production and trade of petrochemicals. A major part is constituted by the plastics (polymer) industry. It directly interfaces with the petroleum industry, especially the downstream sector.

Comp ...

possible.

;1856:William Henry Perkin

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 – 14 July 1907) was a British chemist and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline. Though he failed in tryin ...

synthesizes Perkin's mauve, the first synthetic dye. Created as an accidental byproduct of an attempt to create quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal le ...

from coal tar

Coal tar is a thick dark liquid which is a by-product of the production of coke and coal gas from coal. It is a type of creosote. It has both medical and industrial uses. Medicinally it is a topical medication applied to skin to treat psorias ...

. This discovery is the foundation of the dye synthesis industry, one of the earliest successful chemical industries.

;1857: Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz proposes that carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon mak ...

is tetravalent, or forms exactly four chemical bonds

A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between atoms or ions that enables the formation of molecules and crystals. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds, or through the sharing of ...

.

;1859–1860: Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff (; 12 March 1824 – 17 October 1887) was a German physicist who contributed to the fundamental understanding of electrical circuits, spectroscopy, and the emission of black-body radiation by heated objects.

He ...

and Robert Bunsen

Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen (;

30 March 1811

– 16 August 1899) was a German chemist. He investigated emission spectra of heated elements, and discovered caesium (in 1860) and rubidium (in 1861) with the physicist Gustav Kirchhoff. The Bu ...

lay the foundations of spectroscopy as a means of chemical analysis, which lead them to the discovery of caesium and rubidium. Other workers soon used the same technique to discover indium

Indium is a chemical element with the symbol In and atomic number 49. Indium is the softest metal that is not an alkali metal. It is a silvery-white metal that resembles tin in appearance. It is a post-transition metal that makes up 0.21 parts ...

, thallium

Thallium is a chemical element with the symbol Tl and atomic number 81. It is a gray post-transition metal that is not found free in nature. When isolated, thallium resembles tin, but discolors when exposed to air. Chemists William Crookes an ...

, and helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

.

;1860:Stanislao Cannizzaro

Stanislao Cannizzaro ( , also , ; 13 July 1826 – 10 May 1910) was an Italian chemist. He is famous for the Cannizzaro reaction and for his influential role in the atomic-weight deliberations of the Karlsruhe Congress in 1860.

Biograph ...

, resurrecting Avogadro's ideas regarding diatomic molecules, compiles a table of atomic weight

Relative atomic mass (symbol: ''A''; sometimes abbreviated RAM or r.a.m.), also known by the deprecated synonym atomic weight, is a dimensionless physical quantity defined as the ratio of the average mass of atoms of a chemical element in a giv ...

s and presents it at the 1860 Karlsruhe Congress

The Karlsruhe Congress was an international meeting of chemists held in Karlsruhe, Germany from 3 to 5 September 1860. It was the first international conference of chemistry worldwide.

The meeting

The Karlsruhe Congress was called so that Euro ...

, ending decades of conflicting atomic weights and molecular formulas, and leading to Mendeleev's discovery of the periodic law.

;1862:Alexander Parkes

Alexander Parkes (29 December 1813 29 June 1890) was a metallurgist and inventor from Birmingham, England. He created Parkesine, the first man-made plastic.

Biography

The son of a manufacturer of brass locks, Parkes was apprenticed to Messenge ...

exhibits Parkesine

Celluloids are a class of materials produced by mixing nitrocellulose and camphor, often with added dyes and other agents. Once much more common for its use as photographic film before the advent of safer methods, celluloid's common contemporary ...

, one of the earliest synthetic polymers, at the International Exhibition in London. This discovery formed the foundation of the modern plastics industry.

;1862: Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois publishes the telluric helix, an early, three-dimensional version of the periodic table of the elements.

;1864: John Newlands proposes the law of octaves, a precursor to the periodic law

Periodic trends are specific patterns that are present in the periodic table that illustrate different aspects of a certain element. They were discovered by the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev in the year 1863. Major periodic trends include atom ...

.

;1864:Lothar Meyer

Julius Lothar Meyer (19 August 1830 – 11 April 1895) was a German chemist. He was one of the pioneers in developing the earliest versions of the periodic table of the chemical elements. Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev (his chief rival) and he ...

develops an early version of the periodic table, with 28 elements organized by valence.

;1864:Cato Maximilian Guldberg

Cato Maximilian Guldberg (11 August 1836 – 14 January 1902) was a Norwegian mathematician and chemist. Guldberg is best known as a pioneer in physical chemistry.

Background

Guldberg was born in Christiania (now Oslo), Norway. He was the el ...

and Peter Waage

Peter Waage (29 June 1833 – 13 January 1900) was a Norwegian chemist and professor of chemistry at the University of Kristiania. Along with his brother-in-law Cato Maximilian Guldberg, he co-discovered and developed the law of mass action ...

, building on Claude Louis Berthollet

Claude Louis Berthollet (, 9 December 1748 – 6 November 1822) was a Savoyard-French chemist who became vice president of the French Senate in 1804. He is known for his scientific contributions to theory of chemical equilibria via the mecha ...

's ideas, proposed the law of mass action

In chemistry, the law of mass action is the proposition that the rate of the chemical reaction is directly proportional to the product of the activities or concentrations of the reactants. It explains and predicts behaviors of solutions in dy ...

.C.M. Guldberg and P. Waage,"Studies Concerning Affinity" ''C. M. Forhandlinger: Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiana'' (1864), 35P. Waage, "Experiments for Determining the Affinity Law" ,''Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania'', (1864) 92.C.M. Guldberg, "Concerning the Laws of Chemical Affinity", ''C. M. Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania'' (1864) 111

;1865:Johann Josef Loschmidt

Johann Josef Loschmidt (15 March 1821 – 8 July 1895), who referred to himself mostly as Josef Loschmidt (omitting his first name), was a notable Austrian scientist who performed ground-breaking work in chemistry, physics (thermodynamics, optics, ...

determines exact number of molecules in a mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole", mammals in the family Talpidae, found in Eurasia and North America

* Golden moles, southern African mammals in the family Chrysochloridae, similar to but unrelated to Talpida ...

, later named Avogadro's number

The Avogadro constant, commonly denoted or , is the proportionality factor that relates the number of constituent particles (usually molecules, atoms or ions) in a sample with the amount of substance in that sample. It is an SI defining co ...

.

;1865:Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz, based partially on the work of Loschmidt and others, establishes structure of benzene as a six carbon ring with alternating single and double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betwee ...

s.

;1865:Adolf von Baeyer

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer (; 31 October 1835 – 20 August 1917) was a German chemist who synthesised indigo and developed a nomenclature for cyclic compounds (that was subsequently extended and adopted as part of the IUPAC org ...

begins work on indigo dye, a milestone in modern industrial organic chemistry which revolutionizes the dye industry.

;1869: Dmitri Mendeleev publishes the first modern periodic table, with the 66 known elements organized by atomic weights. The strength of his table was its ability to accurately predict the properties of as-yet unknown elements.

;1873: Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel, working independently, develop a model of

;1869: Dmitri Mendeleev publishes the first modern periodic table, with the 66 known elements organized by atomic weights. The strength of his table was its ability to accurately predict the properties of as-yet unknown elements.

;1873: Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel, working independently, develop a model of chemical bonding

A chemical bond is a lasting attraction between atoms or ions that enables the formation of molecules and crystals. The bond may result from the electrostatic force between oppositely charged ions as in ionic bonds, or through the sharing o ...

that explains the chirality experiments of Pasteur and provides a physical cause for optical activity in chiral compounds.

;1876:Josiah Willard Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs (; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American scientist who made significant theoretical contributions to physics, chemistry, and mathematics. His work on the applications of thermodynamics was instrumental in t ...

publishes ''On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances

In the history of thermodynamics, ''On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances'' is a 300-page paper written by American chemical physicist Willard Gibbs. It is one of the founding papers in thermodynamics, along with German physicist Hermann ...

'', a compilation of his work on thermodynamics and physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistica ...

which lays out the concept of free energy to explain the physical basis of chemical equilibria.

;1877:Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann (; 20 February 1844 – 5 September 1906) was an Austrian physicist and philosopher. His greatest achievements were the development of statistical mechanics, and the statistical explanation of the second law of ther ...

establishes statistical derivations of many important physical and chemical concepts, including entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynam ...

, and distributions of molecular velocities in the gas phase.

;1883:Svante Arrhenius

Svante August Arrhenius ( , ; 19 February 1859 – 2 October 1927) was a Swedish scientist. Originally a physicist, but often referred to as a chemist, Arrhenius was one of the founders of the science of physical chemistry. He received the Nob ...

develops ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

theory to explain conductivity in electrolytes.

;1884:Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff publishes ''Études de Dynamique chimique'', a seminal study on chemical kinetics

Chemical kinetics, also known as reaction kinetics, is the branch of physical chemistry that is concerned with understanding the rates of chemical reactions. It is to be contrasted with chemical thermodynamics, which deals with the direction in ...

.

;1884:Hermann Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fischer projection, a symbolic way of dra ...

proposes structure of purine

Purine is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound that consists of two rings ( pyrimidine and imidazole) fused together. It is water-soluble. Purine also gives its name to the wider class of molecules, purines, which include substituted purines ...

, a key structure in many biomolecules, which he later synthesized in 1898. Also begins work on the chemistry of glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

and related sugars.

;1884:Henry Louis Le Chatelier

Henry Louis Le Chatelier (; 8 October 1850 – 17 September 1936) was a French chemist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He devised Le Chatelier's principle, used by chemists and chemical engineers to predict the effect a changing conditi ...

develops Le Chatelier's principle

Le Chatelier's principle (pronounced or ), also called Chatelier's principle (or the Equilibrium Law), is a principle of chemistry used to predict the effect of a change in conditions on chemical equilibria. The principle is named after French c ...

, which explains the response of dynamic chemical equilibria to external stresses.

;1885:Eugen Goldstein

Eugen Goldstein (; 5 September 1850 – 25 December 1930) was a German physicist. He was an early investigator of discharge tubes, the discoverer of anode rays or canal rays, later identified as positive ions in the gas phase including the h ...

names the cathode ray

Cathode rays or electron beam (e-beam) are streams of electrons observed in discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to el ...

, later discovered to be composed of electrons, and the canal ray

An anode ray (also positive ray or canal ray) is a beam of positive ions that is created by certain types of gas-discharge tubes. They were first observed in Crookes tubes during experiments by the German scientist Eugen Goldstein, in 1886. La ...

, later discovered to be positive hydrogen ions that had been stripped of their electrons in a cathode ray tube. These would later be named protons.

;1893: Alfred Werner discovers the octahedral structure of cobalt complexes, thus establishing the field of coordination chemistry.

;1894–1898: William Ramsay

Sir William Ramsay (; 2 October 1852 – 23 July 1916) was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous element ...

discovers the noble gases

The noble gases (historically also the inert gases; sometimes referred to as aerogens) make up a class of chemical elements with similar properties; under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases with very low ch ...

, which fill a large and unexpected gap in the periodic table and led to models of chemical bonding.

;1897:J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be discovered.

In 1897, Thomson showed that ...

discovers the electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no ...

using the cathode ray tube.

;1898:Wilhelm Wien

Wilhelm Carl Werner Otto Fritz Franz Wien (; 13 January 1864 – 30 August 1928) was a German physicist who, in 1893, used theories about heat and electromagnetism to deduce Wien's displacement law, which calculates the emission of a blackbody ...

demonstrates that canal rays (streams of positive ions) can be deflected by magnetic fields, and that the amount of deflection is proportional to the mass-to-charge ratio. This discovery would lead to the analytical technique known as mass spectrometry.

;1898:Maria Sklodowska-Curie

Marie Salomea Skłodowska–Curie ( , , ; born Maria Salomea Skłodowska, ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934) was a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first ...

and Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie ( , ; 15 May 1859 – 19 April 1906) was a French physicist, a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity, and radioactivity. In 1903, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics with his wife, Marie Curie, and Henri Becq ...

isolate radium

Radium is a chemical element with the symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, but it readily reacts with nitrogen (rathe ...

and polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic character ...

from pitchblende

Uraninite, formerly pitchblende, is a radioactive, uranium-rich mineral and ore with a chemical composition that is largely UO2 but because of oxidation typically contains variable proportions of U3O8. Radioactive decay of the uranium causes t ...

.

;c. 1900: Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

discovers the source of radioactivity as decaying atoms; coins terms for various types of radiation.

20th century

;1903:Mikhail Semyonovich Tsvet

Mikhail Semyonovich Tsvet (Михаил Семёнович Цвет, also spelled Tsvett, Tswett, Tswet, Zwet, and Cvet; 14 May 1872 – 26 June 1919) was a Russian-Italian botanist who invented chromatography. His last name is Russian for "colo ...

invents chromatography

In chemical analysis, chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture into its components. The mixture is dissolved in a fluid solvent (gas or liquid) called the ''mobile phase'', which carries it through a system ( ...

, an important analytic technique.

;1904:Hantaro Nagaoka

was a Japanese physicist and a pioneer of Japanese physics during the Meiji period.

Life

Nagaoka was born in Nagasaki, Japan on August 19, 1865 and educated at the University of Tokyo. After graduating with a degree in physics in 1887, Naga ...

proposes an early nuclear model of the atom, where electrons orbit a dense massive nucleus.

;1905:Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber (; 9 December 186829 January 1934) was a German chemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his invention of the Haber–Bosch process, a method used in industry to synthesize ammonia from nitrogen gas and hydroge ...

and Carl Bosch

Carl Bosch (; 27 August 1874 – 26 April 1940) was a German chemist and engineer and Nobel Laureate in Chemistry. He was a pioneer in the field of high-pressure industrial chemistry and founder of IG Farben, at one point the world's largest ...

develop the Haber process

The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is an artificial nitrogen fixation process and is the main industrial procedure for the production of ammonia today. It is named after its inventors, the German chemists Fritz Haber and ...

for making ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

from its elements, a milestone in industrial chemistry with deep consequences in agriculture.

;1905:Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

explains Brownian motion

Brownian motion, or pedesis (from grc, πήδησις "leaping"), is the random motion of particles suspended in a medium (a liquid or a gas).

This pattern of motion typically consists of random fluctuations in a particle's position insi ...

in a way that definitively proves atomic theory.

;1907: Leo Hendrik Baekeland invents bakelite, one of the first commercially successful plastics.

;1909:

;1909:Robert Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectric ...

measures the charge of individual electrons with unprecedented accuracy through the oil drop experiment

The oil drop experiment was performed by Robert A. Millikan and Harvey Fletcher in 1909 to measure the elementary electric charge (the charge of the electron). The experiment took place in the Ryerson Physical Laboratory at the University of C ...

, confirming that all electrons have the same charge and mass.

;1909:S. P. L. Sørensen invents the pH concept and develops methods for measuring acidity.

;1911:Antonius van den Broek proposes the idea that the elements on the periodic table are more properly organized by positive nuclear charge rather than atomic weight.

;1911:The first Solvay Conference is held in Brussels, bringing together most of the most prominent scientists of the day. Conferences in physics and chemistry continue to be held periodically to this day.

;1911:Ernest Rutherford, Hans Geiger, and Ernest Marsden perform the Geiger–Marsden experiment, gold foil experiment, which proves the nuclear model of the atom, with a small, dense, positive nucleus surrounded by a diffuse electron cloud.

;1912:William Henry Bragg and William Lawrence Bragg propose Bragg's law and establish the field of X-ray crystallography, an important tool for elucidating the crystal structure of substances.

;1912:Peter Debye develops the concept of dipole, molecular dipole to describe asymmetric charge distribution in some molecules.

J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be discovered.

In 1897, Thomson showed that ...

expanding on the work of Wien, shows that charged subatomic particles can be separated by their mass-to-charge ratio, a technique known as mass spectrometry.

;1916:Gilbert N. Lewis publishes "The Atom and the Molecule", the foundation of valence bond theory.

;1921:Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach establish concept of spin (physics), quantum mechanical spin in subatomic particles.

;1923:Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall publish ''Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Substances'', first modern treatise on chemical thermodynamics.

;1923:Gilbert N. Lewis develops the electron pair theory of acid/base (chemistry), base reactions.

;1924:Louis de Broglie introduces the wave-model of atomic structure, based on the ideas of wave–particle duality.

;1925:Wolfgang Pauli develops the Pauli exclusion principle, exclusion principle, which states that no two electrons around a single nucleus may have the same quantum state, as described by four quantum numbers.

;1926:Erwin Schrödinger proposes the Schrödinger equation, which provides a mathematical basis for the wave model of atomic structure.

;1927:Werner Heisenberg develops the uncertainty principle which, among other things, explains the mechanics of electron motion around the nucleus.

;1927:Fritz London and Walter Heitler apply quantum mechanics to explain covalent bonding in the hydrogen molecule, which marked the birth of quantum chemistry.

;1929: Linus Pauling publishes Pauling's rules, which are key principles for the use of X-ray crystallography to deduce molecular structure.

;1931:Erich Hückel proposes Hückel's rule, which explains when a planar ring molecule will have aromaticity, aromatic properties.

;1931:Harold Urey discovers deuterium by fractional distillation, fractionally distilling liquid hydrogen.

;1932:James Chadwick discovers the neutron.

;1932–1934:Linus Pauling and Robert Mulliken quantify electronegativity, devising the scales that now bear their names.

;1935:Wallace Carothers leads a team of chemists at DuPont who invent nylon, one of the most commercially successful synthetic polymers in history.

;1937:Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè perform the first confirmed synthesis of technetium, technetium-97, the first artificially produced element, filling a gap in the periodic table. Though disputed, the element may have been synthesized as early as 1925 by Walter Noddack and others.

;1937:Eugene Houdry develops a method of industrial scale catalytic cracking of petroleum, leading to the development of the first modern oil refinery.

;1937:Pyotr Kapitsa, John F. Allen (physicist), John Allen and Don Misener produce supercooled helium, helium-4, the first zero-viscosity superfluid, a substance that displays quantum mechanical properties on a macroscopic scale.

;1938:Otto Hahn discovers the process of nuclear fission in uranium and thorium.

;1939:Linus Pauling publishes ''The Nature of the Chemical Bond'', a compilation of a decades worth of work on chemical bonding. It is one of the most important modern chemical texts. It explains orbital hybridization, hybridization theory, covalent bonding and ionic bonding as explained through electronegativity, and resonance (chemistry), resonance as a means to explain, among other things, the structure of benzene.

;1940:Edwin McMillan and Philip H. Abelson identify neptunium, the lightest and first synthesized transuranium element, found in the products of uranium Nuclear fission, fission. McMillan would found a lab at University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley that would be involved in the discovery of many new elements and isotopes.

;1941:Glenn T. Seaborg takes over McMillan's work creating new atomic nuclei. Pioneers method of neutron capture and later through other nuclear reactions. Would become the principal or co-discoverer of nine new chemical elements, and dozens of new isotopes of existing elements.

;1944

:Robert Burns Woodward and William von Eggers Doering successfully synthesized of

;1932:James Chadwick discovers the neutron.

;1932–1934:Linus Pauling and Robert Mulliken quantify electronegativity, devising the scales that now bear their names.

;1935:Wallace Carothers leads a team of chemists at DuPont who invent nylon, one of the most commercially successful synthetic polymers in history.

;1937:Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè perform the first confirmed synthesis of technetium, technetium-97, the first artificially produced element, filling a gap in the periodic table. Though disputed, the element may have been synthesized as early as 1925 by Walter Noddack and others.

;1937:Eugene Houdry develops a method of industrial scale catalytic cracking of petroleum, leading to the development of the first modern oil refinery.

;1937:Pyotr Kapitsa, John F. Allen (physicist), John Allen and Don Misener produce supercooled helium, helium-4, the first zero-viscosity superfluid, a substance that displays quantum mechanical properties on a macroscopic scale.

;1938:Otto Hahn discovers the process of nuclear fission in uranium and thorium.

;1939:Linus Pauling publishes ''The Nature of the Chemical Bond'', a compilation of a decades worth of work on chemical bonding. It is one of the most important modern chemical texts. It explains orbital hybridization, hybridization theory, covalent bonding and ionic bonding as explained through electronegativity, and resonance (chemistry), resonance as a means to explain, among other things, the structure of benzene.

;1940:Edwin McMillan and Philip H. Abelson identify neptunium, the lightest and first synthesized transuranium element, found in the products of uranium Nuclear fission, fission. McMillan would found a lab at University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley that would be involved in the discovery of many new elements and isotopes.

;1941:Glenn T. Seaborg takes over McMillan's work creating new atomic nuclei. Pioneers method of neutron capture and later through other nuclear reactions. Would become the principal or co-discoverer of nine new chemical elements, and dozens of new isotopes of existing elements.

;1944

:Robert Burns Woodward and William von Eggers Doering successfully synthesized of quinine