Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Biography

Early life

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James (1758–1832) and Margaret Aitken Carlyle (1771–1853) in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland.

Thomas Carlyle was born on 4 December 1795 to James (1758–1832) and Margaret Aitken Carlyle (1771–1853) in the village of Ecclefechan in Dumfriesshire in southwest Scotland. Edinburgh, the ministry and teaching (1809–1818)

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the

In November 1809 at nearly fourteen years of age, Carlyle walked one hundred miles from his home in order to attend the I read Gibbon, and then first clearly saw thatChristianity Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...was not true. Then came the most trying time of my life. I should either have gone mad or made an end of myself had I not fallen in with some very superior minds.

Mineralogy, law and first publications (1818–1821)

In the summer of 1818, following a "Tour" with Irving through ""Conversion": Leith Walk and Hoddam Hill (1821–1826)

During this time, Carlyle struggled with what he described as "the dismallest Lernean Hydra of problems, spiritual, temporal, eternal". Spiritual doubt, lack of success in his endeavours, and dyspepsia were all damaging his physical and mental health, for which he found relief only in "sea-bathing". In early July 1821, an "incident" occurred to Carlyle in Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review'', and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On

Carlyle wrote several articles in July, August and September, and in November began a translation of Adrien-Marie Legendre">Adrien Marie Legendre's ''Elements of Geometry''. In January 1822, Carlyle wrote "Goethe's Faust" for the ''New Edinburgh Review'', and shortly afterwards began a tutorship for the distinguished Buller family, tutoring Charles Buller and his brother Arthur William Buller until July; he would work for the family until July 1824. Carlyle completed the Legendre translation in July 1822, having prefixed his own essay "On Marriage, Comely Bank and Craigenputtock (1826–1834)

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Carlyle were married at the Welsh family farm in

In October 1826, Thomas and Jane Carlyle were married at the Welsh family farm in  In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to

In May 1828, the Carlyles moved to  Most notably, he wrote ''

Most notably, he wrote ''Chelsea (1834–1845)

In June 1834, the Carlyles moved into 5 Cheyne Row, Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in ''

Carlyle eventually decided to publish ''Sartor'' serially in '' During Carlyle's lecture series, '' The French Revolution: A History'' was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to

During Carlyle's lecture series, '' The French Revolution: A History'' was officially published. It marked his career breakthrough. At the end of the year, Carlyle reported to  In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as ''

In May 1840, Carlyle gave his fourth and final set of lectures, which were published in 1841 as ''Journeys to Ireland and Germany (1846–1865)

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy for a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the

Carlyle visited Ireland in 1846 with Charles Gavan Duffy for a companion and guide, and wrote a series of brief articles on the Final years (1866–1881)

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall,

Carlyle travelled to Scotland to deliver his "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" as Rector in April 1866. During his trip, he was accompanied by John Tyndall,  Amidst controversy over governor

Amidst controversy over governor  In the spring of 1874, Carlyle accepted the ''

In the spring of 1874, Carlyle accepted the ''Philosophy

Carlyle's religious, historical and political thought has long been the subject of debate. In the 19th century, he was "an enigma" according to Ian Campbell in the '' Dictionary of Literary Biography'', being "variously regarded as sage and impious, a moral leader, a moral desperado, a radical, a conservative, a Christian." Carlyle continues to perplex scholars in the 21st century, as Kenneth J. Fielding quipped in 2005: "A problem in writing about Carlyle and his beliefs is that people think that they know what they are."

Carlyle identified two philosophical precepts. The first is derived from Novalis: "The True philosophical Act is annihilation of self (''Selbsttödtung''); this is the real beginning of all Philosophy; all requisites for being a Disciple of Philosophy point hither." The second is derived from Goethe: "It is only with Renunciation (''Entsagen'') that Life, properly speaking, can be said to begin." Through ''Selbsttödtung'' (annihilation of self), liberation from

Carlyle's religious, historical and political thought has long been the subject of debate. In the 19th century, he was "an enigma" according to Ian Campbell in the '' Dictionary of Literary Biography'', being "variously regarded as sage and impious, a moral leader, a moral desperado, a radical, a conservative, a Christian." Carlyle continues to perplex scholars in the 21st century, as Kenneth J. Fielding quipped in 2005: "A problem in writing about Carlyle and his beliefs is that people think that they know what they are."

Carlyle identified two philosophical precepts. The first is derived from Novalis: "The True philosophical Act is annihilation of self (''Selbsttödtung''); this is the real beginning of all Philosophy; all requisites for being a Disciple of Philosophy point hither." The second is derived from Goethe: "It is only with Renunciation (''Entsagen'') that Life, properly speaking, can be said to begin." Through ''Selbsttödtung'' (annihilation of self), liberation from Natural Supernaturalism

Carlyle rejected doctrines which profess to fully know the true nature of God, believing that to possess such knowledge is impossible. In an 1835 letter, he asked, "''Wer darf ihn'' NENNEN ho dares name him I dare not, and do not", while rejecting charges ofFinally assure yourself I am neither Pagan nor Turk, nor circumcised Jew, but an unfortunate Christian individual resident at Chelsea in ''this'' year of Grace; neither Pantheist nor Pottheist, nor anyWith this empirical basis, Carlyle conceived of a "new Mythus", Natural Supernaturalism. FollowingTheist Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...or ''ist'' whatsoever; having the most decided contem tfor all manner of System-builders and Sectfounders—as far as contempt may be com atiblewith so mild a nature; feeling well beforehand (taught by long experience) that all such are and even must be ''wrong''. By God's blessing, one has got two eyes to look with; also a mind capable of knowing, of believing: that is all the creed I will at this time insist on.

the sacred mystery of the Universe; what Goethe calls 'the open secret.' . . . open to all, seen by almost none! That divine mystery, which lies everywhere in all Beings, 'the Divine Idea of the World,' that which lies at 'the bottom of Appearance,' asThe "Divine Idea of the World", the belief in an eternal, omnipresent and metaphysical order which lies in the "unknown Deep" of nature, is at the core of Natural Supernaturalism.Fichte Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Ka ...styles it; of which all Appearance . . . is but the ''vesture'', the embodiment that renders it visible.

Bible of Universal History

Carlyle revered what he called the "Bible of Universal History", a "real Prophetic Manuscript" which incorporates the poetic and the factual to show the divine reality of existence. For Carlyle, "the right interpretation of Reality and History" is the highest form of poetry, and "true History" is "the only possible Epic". He imaged the "burning of a World-Phoenix" to represent the cyclical nature of civilisations as they undergo death and " ''Palingenesia'''', or Newbirth''". Periods of creation and destruction do overlap, however, and before a World-Phoenix is completely reduced to ashes, there are "organic filaments, mysteriously spinning themselves", elements of regeneration amidst degeneration, such as hero-worship, literature, and the unbreakable connection between all human beings. Akin to the seasons, societies have autumns of dying faiths, winters of decadent atheism, springs of burgeoning belief and brief summers of true religion and government. Carlyle saw history since the

Carlyle revered what he called the "Bible of Universal History", a "real Prophetic Manuscript" which incorporates the poetic and the factual to show the divine reality of existence. For Carlyle, "the right interpretation of Reality and History" is the highest form of poetry, and "true History" is "the only possible Epic". He imaged the "burning of a World-Phoenix" to represent the cyclical nature of civilisations as they undergo death and " ''Palingenesia'''', or Newbirth''". Periods of creation and destruction do overlap, however, and before a World-Phoenix is completely reduced to ashes, there are "organic filaments, mysteriously spinning themselves", elements of regeneration amidst degeneration, such as hero-worship, literature, and the unbreakable connection between all human beings. Akin to the seasons, societies have autumns of dying faiths, winters of decadent atheism, springs of burgeoning belief and brief summers of true religion and government. Carlyle saw history since the Heroarchy (Government of Heroes)

As with history, Carlyle believed that "Society is founded on Hero-worship. All dignities of rank, on which human association rests, are what we may call a ''Hero''archy (Government of Heroes)". This fundamental assertion about the nature of society itself informed his political doctrine. Noting that the etymological root meaning of the word "King" is "Can" or "Able", Carlyle put forth his ideal government in "The Hero as King":Find in any country the Ablest Man that exists there; raise ''him'' to the supreme place, and loyally reverence him: you have a perfect government for that country; no ballot-box, parliamentary eloquence, voting, constitution-building, or other machinery whatsoever can improve it a whit. It is in the perfect state; an ideal country.Carlyle did not believe in

The Ablest Man; he means also the truest-hearted, justest, the Noblest Man: what he ''tells us to do'' must be precisely the wisest, fittest, that we could anywhere or anyhow learn;—the thing which it will in all ways behoove us, with right loyal thankfulness, and nothing doubting, to do! Our ''doing'' and life were then, so far as government could regulate it, well regulated; that were the ideal ofIt was for this reason that he regarded the Reformation, theconstitutions A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed. When these prin ....

Chivalry of Labour

Carlyle advocated a new kind of hero for the age ofGlossary

The 1907 edition of ''Style

Carlyle believed that his time required a new approach to writing:But finally do you reckon this really a time for Purism of Style; or that Style (mere dictionary style) has much to do with the worth or unworth of a Book? I do not: with whole ragged battallions of Scott's-Novel Scotch, with Irish, German, French and even Newspaper Cockney (when "Literature" is little other than a Newspaper) storming in on us, and the whole structure of our Johnsonian English breaking up from its foundations,—revolution ''there'' as visible as anywhere else!Carlyle's style lends itself to several nouns, the earliest being Carlylism from 1841. The ''

Carlylese

At the beginning of his literary career, Carlyle worked to develop his own style, cultivating one of intense energy and visualisation, characterised not by "balance, gravity, and composure" but "imbalance, excess, and excitement." Even in his early anonymous periodical essays his writing distinguished him from his contemporaries. Carlyle's writing in ''Sartor Resartus'' is described as "a distinctive mixture of exuberant poetic rhapsody, Germanic speculation, and biblical exhortation, which Carlyle used to celebrate the mystery of everyday existence and to depict a universe suffused with creative energy." Carlyle's approach to historical writing was inspired by a quality that he found in the works of Goethe, Bunyan andCoinages

The present table represents data gathered from ''Oxford English Dictionary Online'', 2012. An explanatory footnote is provided for each "Type". Over fifty percent of these entries come from ''Sartor Resartus'', ''French Revolution'', and ''History of'' ''Frederick the Great''. Of the 547 First Quotations cited by the ''O.E.D.'', 87 or 16% are listed as being "in common use today."Humour

Carlyle's sense of humour and use of humorous characters was shaped by early readings ofAllusion

Carlyle's writing is highly allusive.Reception

The earliest literary criticism on Carlyle is an 1835 letter from Sterling, who complained of the "positively barbarous" use of words in ''Sartor'', such as "environment," "stertorous," and "visualised," words "without any authority" that are now widely used.Indeed, for fluency and skill in the use of the English tongue, he is a master unrivalled. His felicity and power of expression surpass even his special merits as historian and critic. . . . we had not understood the wealth of the language before. . . . He does not go to the dictionary, the wordbook, but to the word-manufactory itself, and has made endless work for the lexicographers . . . it would be well for any who have a lost horse to advertise, or a town-meeting warrant, or a sermon, or a letter to write, to study this universal letter-writer, for he knows more than the grammar or the dictionary.

Character

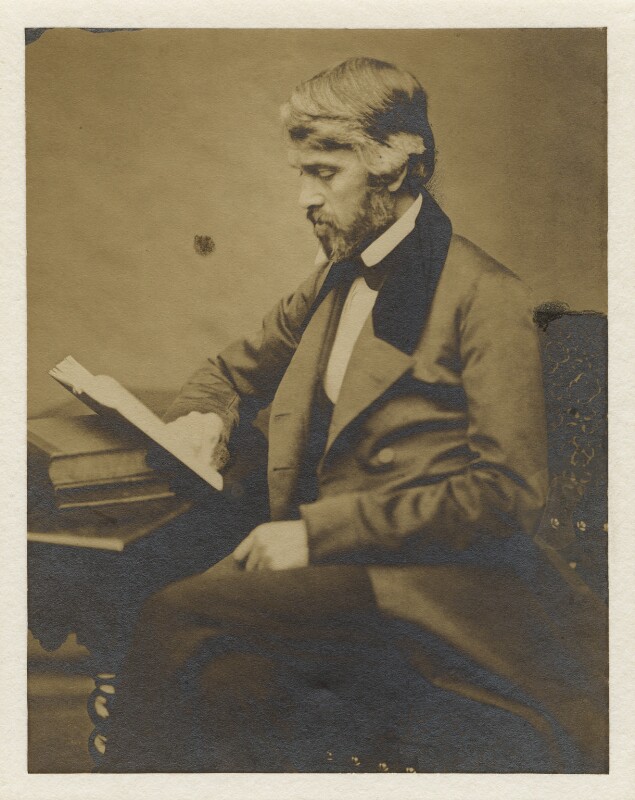

Froude recalled his first impression of Carlyle:

Froude recalled his first impression of Carlyle:He was then fifty-four years old; tall (about five feet eleven), thin, but at that time upright, with no signs of the later stoop. His body was angular, his face beardless, such as it is represented in Woolner's medallion, which is by far the best likeness of him in the days of his strength. His head was extremely long, with the chin thrust forward; his neck was thin; the mouth firmly closed, the under lip slightly projecting; the hair grizzled and thick and bushy. His eyes, which grew lighter with age, were then of a deep violet, with fire burning at the bottom of them, which flashed out at the least excitement. The face was altogether most striking, most impressive in every way.He was often recognised by his

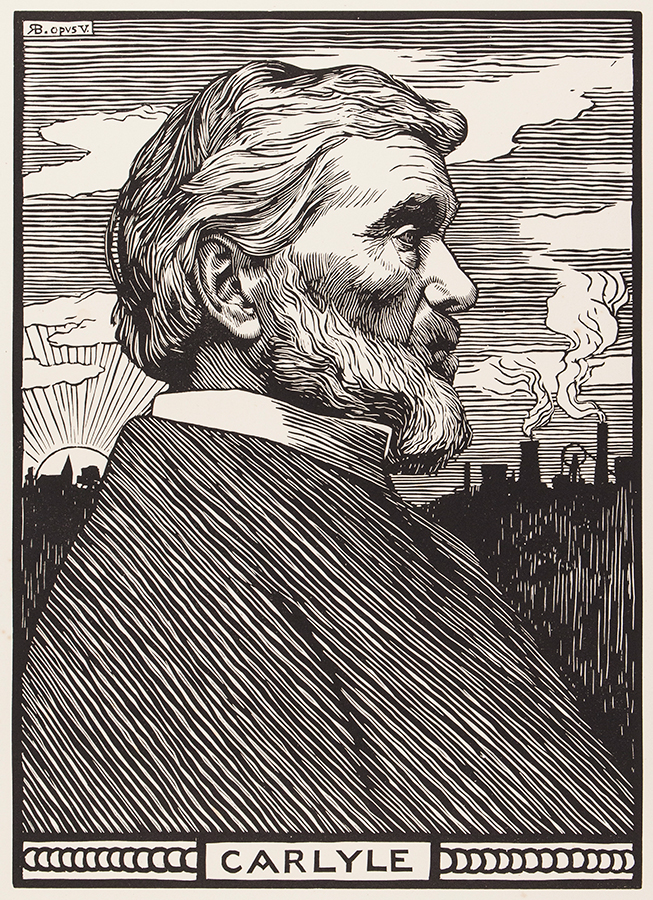

XVIII. Carlyle

. The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Vol. X. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company (published 1904).

Legacy

Influence

It is an idle question to ask whether his books will be read a century hence: if they were all burnt as the grandest ofCarlyle's two most important followers were Emerson and Ruskin. In the 19th century, Emerson was often thought of as "the American Carlyle". He sent Carlyle one of his books in 1870 with the inscription, "To the General in Chief from his Lieutenant". In 1854, Ruskin made his first public acknowledgement that Carlyle was the author to whom he "owed more than to any other living writer". After reading Ruskin's ''Suttee Sati or suttee is a Hindu practice, now largely historical, in which a widow sacrifices herself by sitting atop her deceased husband's funeral pyre. Quote: Between 1943 and 1987, some thirty women in Rajasthan (twenty-eight, according to offic ...s on his funeral pile, it would be only like cutting down an oak after its acorns have sown a forest. For there is hardly a superior or active mind of this generation that has not been modified by Carlyle's writings; there has hardly been an English book written for the last ten or twelve years that would not have been different if Carlyle had not lived.

Literature

"The most explosive impact in English literature during the nineteenth century is unquestionably Thomas Carlyle's", writes Lionel Stevenson. "From about 1840 onward, no author of prose or poetry was immune from his influence." Authors on whom Carlyle's influence was particularly strong include

Authors on whom Carlyle's influence was particularly strong include Philosophy

J. H. Muirhead wrote that Carlyle "exercised an influence in England and America that no other did upon the course of philosophical thought of his time". Ralph Jessop has shown that Carlyle powerfully forwarded the Scottish School of Common Sense and reinforced it by way of further engagement withHistoriography

David R. Sorensen affirms that Carlyle "redeemed the study of history at a moment when it was being threatened by a host of convergent forces, including religious dogmatism,Social and political movements

Chandler, writing in 1970, said that the influence of Carlyle's medievalism can be found "in much of the social legislation of the past hundred and more years". It is perhaps most pronounced in Forster's Education Act, the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act, the Factory Acts, and the rise of such practices as business ethics and profit sharing throughout the 19th- and early 20th-centuries. His attacks on ''laissez-faire'' became an important inspiration for Progressivism in the United States, U.S. progressives, influencing the creations of the American Association for Labor Legislation, the National Child Labor Committee and the National Consumers League. His economic statism influenced the progressive American Economic Association's early concept of "intelligent social engineering" (which has been described as Elitism, elitist and Eugenics, eugenicist). Leopold Caro credited Carlyle with influencing the social altruism of Henry Ford. Carlyle's influence on modern socialism has been described as "constitutive". Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels cited him in ''The Condition of the Working Class in England'' (1844–1845), The Holy Family (book), ''The Holy Family'' (1845), and ''The Communist Manifesto'' (1848). Alexander Herzen and Vasily Botkin valued his writings, the former calling him "a Scotch Proudhon." He was one of the main "intellectual sources" for Christian socialism. His importance to the British ''fin de siècle'' labour movement was acknowledged by major figures such as William Morris, Keir Hardie and Robert Blatchford. Individual reformers took inspiration from him, including Octavia Hill, Emmeline Pankhurst and Jane Addams. Carlyle's aversion to the label notwithstanding, 19th-centuy conservatives were influenced by him. Morris Edmund Speare cites Carlyle as "one of the greatest influences" on Disraeli's life. Robert Blake, Baron Blake, Robert Blake links the two as "romantic, conservative, organic thinkers who revolted against Benthamism and the legacy of eighteenth-century rationalism." Leslie Stephen noted Carlyle's influence on his brother James Fitzjames Stephen in the early 1870s.

Nationalist movements also looked to Carlyle. He was admired by the Young Irelanders, despite his opposition to their cause. Duffy wrote that in Carlyle, they found a "very welcome" teacher, who "confirmed their determination to think for themselves", and that his writings were "often a cordial to their hearts in doubt and difficulty". Carlyle's philosophy was popular in the Antebellum South and eventual Confederacy (American Civil War), Confederacy. In 1848, ''The Southern Quarterly Review'' declared: "The spirit of Thomas Carlyle is abroad in the land." American historian William Dodd (ambassador), William E. Dodd wrote that Carlyle's "doctrine of social subordination and class distinction . . . was all that Thomas Roderick Dew, Dew and William Harper (South Carolina politician), Harper and John C. Calhoun, Calhoun and James Henry Hammond, Hammond desired. The greatest Realism (philosophical), realist in England had weighed their system and found it just and humane." Southern sociologist George Fitzhugh's notions of palingenesis, multi-racial slavery, and authoritarianism were profoundly influenced by Carlyle (as was his prose style). Richard Wagner used Carlyle, whom he called a "great thinker", to justify his later German nationalism. References to Carlyle appear in the writings of Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi throughout his life.

More recently, figures associated with the Nouvelle Droite, the Neoreactionary movement, and the alt-right have claimed Carlyle as an influence on their approach to metapolitics. At a meeting of the New Right (UK), New Right in London in July 2008, English artist Jonathan Bowden delivered a lecture in which he said, "All of our great thinkers are shooting arrows into the future. And Carlyle is one of them." In 2010, American blogger Curtis Yarvin labeled himself a Carlylean "the way a Marxism, Marxist is a Marxist." New Zealand-born writer Kerry Bolton wrote in 2020 that Carlyle's works "could be the ideological basis of a true British Right" and that they "remain as timeless foundations on which the Anglophone Right can return to its actual premises."

Carlyle's aversion to the label notwithstanding, 19th-centuy conservatives were influenced by him. Morris Edmund Speare cites Carlyle as "one of the greatest influences" on Disraeli's life. Robert Blake, Baron Blake, Robert Blake links the two as "romantic, conservative, organic thinkers who revolted against Benthamism and the legacy of eighteenth-century rationalism." Leslie Stephen noted Carlyle's influence on his brother James Fitzjames Stephen in the early 1870s.

Nationalist movements also looked to Carlyle. He was admired by the Young Irelanders, despite his opposition to their cause. Duffy wrote that in Carlyle, they found a "very welcome" teacher, who "confirmed their determination to think for themselves", and that his writings were "often a cordial to their hearts in doubt and difficulty". Carlyle's philosophy was popular in the Antebellum South and eventual Confederacy (American Civil War), Confederacy. In 1848, ''The Southern Quarterly Review'' declared: "The spirit of Thomas Carlyle is abroad in the land." American historian William Dodd (ambassador), William E. Dodd wrote that Carlyle's "doctrine of social subordination and class distinction . . . was all that Thomas Roderick Dew, Dew and William Harper (South Carolina politician), Harper and John C. Calhoun, Calhoun and James Henry Hammond, Hammond desired. The greatest Realism (philosophical), realist in England had weighed their system and found it just and humane." Southern sociologist George Fitzhugh's notions of palingenesis, multi-racial slavery, and authoritarianism were profoundly influenced by Carlyle (as was his prose style). Richard Wagner used Carlyle, whom he called a "great thinker", to justify his later German nationalism. References to Carlyle appear in the writings of Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi throughout his life.

More recently, figures associated with the Nouvelle Droite, the Neoreactionary movement, and the alt-right have claimed Carlyle as an influence on their approach to metapolitics. At a meeting of the New Right (UK), New Right in London in July 2008, English artist Jonathan Bowden delivered a lecture in which he said, "All of our great thinkers are shooting arrows into the future. And Carlyle is one of them." In 2010, American blogger Curtis Yarvin labeled himself a Carlylean "the way a Marxism, Marxist is a Marxist." New Zealand-born writer Kerry Bolton wrote in 2020 that Carlyle's works "could be the ideological basis of a true British Right" and that they "remain as timeless foundations on which the Anglophone Right can return to its actual premises."

Art

Carlyle's medievalist critique of industrial practice and political economy was an early utterance of what would become the spirit of both the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts movement, and several leading members recognised his importance. John William Mackail, friend and official biographer of William Morris, wrote, that in the years of Morris and Edward Burne-Jones attendance at University of Oxford, Oxford, ''Past and Present'' stood as "inspired and absolute truth." Morris read a letter from Carlyle at the first public meeting of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Fiona MacCarthy, a recent biographer, affirmed that Morris was "deeply and lastingly" indebted to Carlyle. William Holman Hunt considered Carlyle to be a mentor of his. He used Carlyle as one of the models for the head of Christ in ''The Light of the World (painting), The Light of the World'' and showed great concern for Carlyle's portrayal in Ford Madox Brown's painting ''Work (painting), Work'' (1865). Carlyle helped Thomas Woolner to find work early in his career and throughout, and the sculptor would become "a kind of surrogate son" to the Carlyles, referring to Carlyle as "the dear old philosopher". Phoebe Anna Traquair depicted Carlyle, one of her favourite writers, in murals painted for the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, Royal Hospital for Sick Children and St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (Episcopal), St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh. According to Marylu Hill, the Roycrofters were "very influenced by Carlyle's words about work and the necessity of work", with his name appearing frequently in their writings, which are held at Villanova University.

apRoberts writes that Carlyle "did much to set the stage for the Aesthetic Movement" through both his German and original writings, noting that he even popularised (if not introduced) the term "''Aesthetics, Æesthetics''" into the English language, leading her to declare him as "the apostle of aesthetics in England, 1825–27." Carlyle's rhetorical style and his views on art also provided a foundation for aestheticism, particularly that of Walter Pater, Wilde, and W. B. Yeats.

Carlyle's medievalist critique of industrial practice and political economy was an early utterance of what would become the spirit of both the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts movement, and several leading members recognised his importance. John William Mackail, friend and official biographer of William Morris, wrote, that in the years of Morris and Edward Burne-Jones attendance at University of Oxford, Oxford, ''Past and Present'' stood as "inspired and absolute truth." Morris read a letter from Carlyle at the first public meeting of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Fiona MacCarthy, a recent biographer, affirmed that Morris was "deeply and lastingly" indebted to Carlyle. William Holman Hunt considered Carlyle to be a mentor of his. He used Carlyle as one of the models for the head of Christ in ''The Light of the World (painting), The Light of the World'' and showed great concern for Carlyle's portrayal in Ford Madox Brown's painting ''Work (painting), Work'' (1865). Carlyle helped Thomas Woolner to find work early in his career and throughout, and the sculptor would become "a kind of surrogate son" to the Carlyles, referring to Carlyle as "the dear old philosopher". Phoebe Anna Traquair depicted Carlyle, one of her favourite writers, in murals painted for the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, Royal Hospital for Sick Children and St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (Episcopal), St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh. According to Marylu Hill, the Roycrofters were "very influenced by Carlyle's words about work and the necessity of work", with his name appearing frequently in their writings, which are held at Villanova University.

apRoberts writes that Carlyle "did much to set the stage for the Aesthetic Movement" through both his German and original writings, noting that he even popularised (if not introduced) the term "''Aesthetics, Æesthetics''" into the English language, leading her to declare him as "the apostle of aesthetics in England, 1825–27." Carlyle's rhetorical style and his views on art also provided a foundation for aestheticism, particularly that of Walter Pater, Wilde, and W. B. Yeats.

Reputation

Few figures in the history of English literature have been so highly esteemed and then utterly neglected within such a short timespan as Thomas Carlyle. Tennyson divided the history of his reputation into three chronological periods:

# Carlyle's lifetime (to 1881): The Popular Period

# From Carlyle's Death to about 1930: The Reactionary Period

# From 1930 to the Present: The Scholarly-Critical Period

He also provides a brief overview of these developments:

Few figures in the history of English literature have been so highly esteemed and then utterly neglected within such a short timespan as Thomas Carlyle. Tennyson divided the history of his reputation into three chronological periods:

# Carlyle's lifetime (to 1881): The Popular Period

# From Carlyle's Death to about 1930: The Reactionary Period

# From 1930 to the Present: The Scholarly-Critical Period

He also provides a brief overview of these developments:If we were plotting the whole course of Carlyle's reputation through the three periods on a graph, we would note a generally rising curve in Period I up to a very high peak towards the end of his life, a drastic plunge in Period II to a valley almost as deep as the peak was high, and a cautious rise in Period III to a modest eminence but with perhaps a further rise in prospect.

Carlyle's lifetime (to 1881): The Popular Period

"If one had to settle upon a single word to characterize the Victorian view of Carlyle, that word should be—Teacher", writes Tennyson. This designation is supported by Harriet Martineau's 1849 assessment of Carlyle: "Whether we call him philosopher, poet, or moralist, he is the first teacher of our generation." For Victorian readers, the Teacher could easily become the Philosopher or the Theologian, and many attempted to extract Carlyle's "system" from his writings. Tennyson draws the connection from teacher to prophet and sage, two frequently used nouns when describing Carlyle. Tennyson considers Froude's biography (1882–1884) as at once "the shining example of the Victorian view of Carlyle" in its reverent adherence to Carlyle's message and the herald of "a new and rather untidy phase of Carlyle's reputation" for its focus on his personal relationships, particularly with his wife.From Carlyle's Death to about 1930: The Reactionary Period

Once the Teacher, Carlyle has become the Denouncer. In this stage, the "dominant tone" of negativity is "set by what seemed to be Froude's undermining of Carlyle's reputation as a man and thinker." The focus turned away from Carlyle's "teachings" and towards negative aspects of Carlyle's personal life; it became fashionable to "denounce the denouncer". Owen Dudley Edwards remarked that in this period, "Carlyle was known more than read". As Campbell describes:

Once the Teacher, Carlyle has become the Denouncer. In this stage, the "dominant tone" of negativity is "set by what seemed to be Froude's undermining of Carlyle's reputation as a man and thinker." The focus turned away from Carlyle's "teachings" and towards negative aspects of Carlyle's personal life; it became fashionable to "denounce the denouncer". Owen Dudley Edwards remarked that in this period, "Carlyle was known more than read". As Campbell describes:The effect of Froude’s work in the years following Carlyle’s death was extraordinary. Almost overnight, it seemed, Carlyle plunged from his position as Sage of Chelsea and Grand Old Victorian to the object of puzzled dislike, or even of revulsion.Tennyson distinguishes two camps that arose from this state of affairs—the Loyalists, those who knew and admired Carlyle, and the Revisionists, those who supported Froude's "undermining". Large amounts of material were published in response to the provocations of the Revisionists, so, in a sense, their approach "dominat[ed] Carlyle scholarship for many years". Tennyson observes that the effects of Froude's legacy are still felt in the way that Carlyle is read and perceived, as the controversy is better known than Carlyle's writings. Similar to Froude's biography, two publications from this time, David Alec Wilson's biography (1923–1934) and Isaac Watson Dyer's bibliography (1928), provide the "last gasp" of the Reactionary period in their open Loyalist partiality, while also ushering in a new era in their emphasis on scholarship, accuracy, and facts.

From 1930 to the Present: The Scholarly-Critical Period

Whereas the Popular Period pictured Carlyle as Teacher and the Reactionary as Denouncer, the Scholarly-Critical Period imaged him as Influence. In the 1930s, scholarly attention to Carlyle increased, and despite hostilities during and after the Second World War, the general upward trend resumed in the 1950s. For the first time, it was possible "to write about Carlyle without necessarily appearing either as his sycophant or as his grim-eyed detractor." The "scholarly" centerpiece of this period is the ''Collected Letters'', a correspondence whose sheer size (50 volumes) and timespan of composition (1812–1881) testifies to the enduring importance of Carlyle both as an individual and as a means through which to view his era. On the "critical" end, there was a new emphasis on the literary and technical aspects of Carlyle's work, inspired by John Holloway's ''The Victorian Sage'' (1953) and continued in further studies. The dual approach to Carlyle as Influence and Carlyle as literary genius brought forth a "palingenesis" in Carlyle studies, which would reaffirm Carlyle as pre-eminent among Victorians. Tennyson predicted that a fourth stage would follow: Carlyle as ''Vates'', in whom, as Carlyle spake in "The Hero as Poet", poet and prophet are one. "Despite the pleas of these critics," Cumming reported in 2004, "Carlyle's status as a great, powerful writer has not been rehabilitated even within the universities, and his name is unlikely ever to have the widespread popular currency of such contemporaries as George Eliot, Charles Dickens, or the Brontës." Several factors have contributed to this state of affairs, one of which is Carlyle's resistance to categorisation, limiting his applicability and presence in academic curricula. Another is the common association of Carlyle with racism and fascism. Besides these, the difficulty of his prose can be a challenge to modern readers. Subsequent scholarship has tended stress his influence and his place in the history of ideas.Controversies

Racism and antisemitism

Fielding writes that Carlyle "was often ready to play up to being a caricature of prejudice". Targets for his ire included the French, the Irish, Slavs, Turks, Americans, Catholics, and, most explicitly, blacks and Jews. Duffy recorded Carlyle's response to Duffy's telling him that "he had taught Mitchel to oppose the liberation of the negroes and the emancipation of the Jews."Mitchel, he said, would be found to be right in the end; the black man could not be emancipated from the laws of nature, which had pronounced a very decided decree on the question, and neither could the Jew.Carlyle "resembled most of his contemporaries" in his beliefs about Jews, identifying them with capitalist materialism and outmoded religious orthodoxy. He wished that the English would throw off their "Hebrew Old-Clothes" and abandon the Hebraic element in Christianity, or Christianity altogether. Carlyle had once considered writing a book called ''Exodus from Houndsditch'', "a pealing off of fetid ''Jewhood'' in every sense from myself and my poor bewildered brethren". Froude described Carlyle's aversion to the Jews as "Teutonic". He felt they had contributed nothing to the "wealth" of mankind, comparing "the Jews with their morbid imaginations and foolish sheepskin Targums" to "The Norse with their steel swords guided by fresh valiant hearts and clear veracious understanding". Carlyle refused an invitation by Sir Anthony de Rothschild, 1st Baronet, Baron Rothschild in 1848 to support a Bill in Parliament to allow Emancipation of the Jews in the United Kingdom, voting rights for Jews in the United Kingdom, asking Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, Richard Monckton Milnes in a correspondence how a Jew could "try to be Senator, or even Citizen, of any Country, except his own wretched Palestine," and expressed his hope that they would "arrive" in Palestine "as soon as possible". Henry Crabb Robinson heard Carlyle at dinner in 1837 speak approvingly of slavery. "It is a natural aristocracy, that of ''colour'', and quite right that the stronger and better race should have dominion!" The 1853 pamphlet "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question, Occasional Discourse on the Nigger Question" expressed concern for the excesses of the practice, considering "How to abolish the abuses of slavery, and save the precious thing in it."

Nazi appropriation

From Goethe's recognition of Carlyle as "a moral force of great importance" in 1827 to the celebration of his centennial as though he were a national hero in 1895, Carlyle had long enjoyed a high reputation in Germany. With the rise of Adolf Hitler, many agreed with the assessment of K. O. Schmidt in 1933, who came to see Carlyle as ''den ersten englischen Nationalsozialisten'' (the first English National Socialist). William Joyce (founder of the National Socialist League and the Carlyle Club, a cultural arm of the NSL named for Carlyle) wrote of how "Germany has repaid him for his scholarship on her behalf by honouring his philosophy when it is scorned in Britain." German academics viewed him as having been immersed in and an outgrowth of German culture, just as National Socialism was. They proposed that ''Heroes and Hero-Worship'' justified the ''Führerprinzip'' (Leadership principle). Theodor Jost wrote in 1935: "Carlyle established, in fact, the mission of the Führer historically and philosophically. He fights, himself a Führer, vigorously against the masses, he . . . becomes a pathfinder for new thoughts and forms." Parallels were also drawn between Carlyle's critique of Victorian England in ''Latter-Day Pamphlets'' and Nazi opposition to the Weimar Republic. Some believed that Carlyle was German by blood. Echoing Paul Hensel's earlier claim in 1901 that Carlyle's ''Volkscharakter'' (Folk character) had preserved "the peculiarity of the Low German tribe", Egon Friedell, an anti-Nazi and Jewish Austrian, explained in 1935 that Carlyle's affinity with Germany stemmed from his being "a Scotsman of the lowlands, where the Celts, Celtic imprint is far more marginal than it is with the High Scottish and the Low German element is even stronger than it is in England." Others regarded him, if not ethnically German, as a ''Geist von unserem Geist'' (Spirit from our Spirit), as Karl Richter wrote in 1937: "Carlyle's ethos is the ethos of the Nordic race, Nordic soul par excellence." In 1945, Joseph Goebbels frequently sought consolation from Carlyle's ''History of'' ''Frederick the Great''. Goebbels read passages from the book to Hitler during his last days in the ''Führerbunker''. While some Germans were eager to claim Carlyle for the Reich, others were more aware of incompatibilities. In 1936, Theodor Deimel argued that because of the "profound difference" between Carlyle's philosophical foundation of "a personally shaped religious idea" and the ''Völkisch'' foundation of National Socialism, the designation of Carlyle as the "first National Socialist" is "mistaken". Ernst Cassirer rejected the notion of Carlyle as proto-fascist in ''The Myth of the State'' (1946), emphasizing the moral underpinning of his thought. Tennyson has also commented that Carlyle's anti-modernist and anti-egoist stances disqualify him from association with 20th-century totalitarianism.In literature

This section lists parodies of and references to Carlyle in literature. * William Maginn parodied Carlyle in the "Gallery of Literary Characters" Number 37, appearing in ''Fraser's Magazine'' for June 1833. * In January 1838 Disraeli published a series of political letters in the ''Times'' under the heading of Old England and signed Couer de Lion, which imitated Carlyle's style. * Carlyle is cast as Collins in "The Onyx Ring," a tale by John Sterling (author), John Sterling which first appeared in ''Bibliography

By Carlyle

Major works

The standard edition of Carlyle's works is the ''Works in Thirty Volumes'', also known as the ''Centenary Edition''. The date given is when the work was "originally published." * ** Vol. I. ''Marginalia

This is a list of selected books, pamphlets and broadsides uncollected in the ''Miscellanies'' through 1880 as well as posthumous first editions and unpublished manuscripts. *Ireland and Sir Robert Peel

' (1849) * ''Legislation for Ireland'' (1849) *

Ireland and the British Chief Governor

' (1849) * Froude, James Anthony, ed. (1881). ''Reminiscences''. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. * ''Reminiscences of My Irish Journey in 1849'' (1882). London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. * ''Last Words of Thomas Carlyle: On Trades-Unions, Promoterism and the Signs of the Times'' (1882). 67 Princes Street, Edinburgh: William Paterson. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1883). ''The Correspondence of Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo Emerson''. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1886). ''Early Letters of Thomas Carlyle''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * ''Thomas Carlyle's Counsels to a Literary Aspirant: A Hitherto Unpublished Letter of 1842 and What Came of Them'' (1886). Edinburgh: James Thin, South Bridge. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1887). ''Reminiscences''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1887). ''Correspondence Between Goethe and Carlyle''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1888). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle''. London and New York: Macmillan and Co. * ''Thomas Carlyle on the Repeal of the Union'' (1889). London: Field & Tuer, the Leadenhall Press. * Newberry, Percy, ed. (1892). ''Rescued Essays of Thomas Carlyle''. The Leadenhall Press. * ''Last Words of Thomas Carlyle'' (1892). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. * Karkaria, R. P., ed. (1892). ''Lectures on the History of Literature''. London: Curwen, Kane & Co. * Joseph Reay Greene, Greene, J. Reay, ed. (1892). ''Lectures on the History of Literature''. London: Ellis and Elvey. * Carlyle, Alexander, ed. (1898). ''Historical Sketches of Notable Persons and Events in the Reigns of James I and Charles I''. London: Chapman and Hall Limited. * Norton, Charles Eliot, ed. (1898). ''Two Note Books of Thomas Carlyle''. New York: The Grolier Club. * Copeland, Charles Townsend, ed. (1899). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle to His Youngest Sister''. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. * Jones, Samuel Arthur, ed. (1903). ''Collecteana''. Canton, Pennsylvania: The Kirgate Press. * Carlyle, Alexander, ed. (1904). ''New Letters of Thomas Carlyle''. London: The Bodley Head. * * * Carlyle, Alexander, ed. (1923). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle to John Stuart Mill, John Sterling and Robert Browning''. London: T. Fisher Unwin LTD. * Brooks, Richard Albert Edward, ed. (1940). ''Journey to Germany, Autumn 1858''. New Haven: Yale University Press. * Graham Jr., John, ed. (1950). ''Letters of Thomas Carlyle to William Graham''. Princeton: Princeton University Press. * Shine, Hill, ed. (1951). ''Carlyle's Unfinished History of German Literature''. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. * Bliss, Trudy, ed. (1953). ''Letters to His Wife''. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. * * * * * * Henderson, Heather, ed. (1979). ''Wooden-Headed Publishers and Locust-Swarms of Authors''. University of Edinburgh. * Campbell, Ian, ed. (1980). ''Thomas and Jane: Selected Letters from the Edinburgh University Library Collection''. Edinburgh. * * * * * Tarr, Rodger L.; McClelland, Fleming, eds. (1986). ''The Collected Poems of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle''. Greenwood, Florida: The Penkevill Publishing Company. * * * * * Tom Hubbard, Hubbard, Tom (2005), "Carlyle, France and Germany in 1870", in Hubbard, Tom (2022), ''Invitation to the Voyage: Scotland, Europe and Literature'', Rymour, pp. 44 - 46,

Scholarly editions

* * * * * * ** * * *Memoirs, etc.

* * * * * * * * * * * * Charles Eliot Norton, Norton, Charles Eliot (1886)"Recollections of Carlyle"

''The New Princeton Review''. 2 (4): 1–19. * *

Biographies

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Julian Symons, Symons, Julian (1952). ''Thomas Carlyle: The Life and Ideas of a Prophet.'' New York: Oxford University Press. * *Secondary sources

* * Augustine Birrell, Birrell, Augustine"Carlyle," from ''Obiter Dicta''

(New York: Chas. Scribner's Sons, 1885). * * * * * * * * * * Harrold, Charles Frederick (1934). ''Carlyle and German Thought: 1819–1834''. New Haven: Yale University Press. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Rosenberg, John D. (1985). ''Carlyle and the Burden of History.'' Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. * Rosenberg, Philip (1974). ''The Seventh Hero: Thomas Carlyle and the Theory of Radical Activism''. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. * * * * * * * * * * * * * Vanden Bossche, Chris R. (1991).

'. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. * * * *

Explanatory notes

References

External links

''Carlyle Studies Annual''

on JSTOR

The Norman and Charlotte Strouse Edition of the Writings of Thomas Carlyle

''The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle''

The Carlyle Society of Edinburgh

The Ecclefechan Carlyle Society

Thomas & Jane Carlyle's Craigenputtock

the official site *

Electronic editions

* * * *at PoetryFoundation.org

''The Carlyle Letters Online''

* ''The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily''

Thomas Carlyle's translation (1832) from the German of Goethe's ''Märchen or Das Märchen''

Archival material

* * A guide to the hdl:10079/fa/beinecke.carlyle, Thomas Carlyle Collection at thBeinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle Photographs

at the Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collections {{DEFAULTSORT:Carlyle, Thomas Thomas Carlyle, 1795 births 1881 deaths 19th-century biographers 19th-century essayists 19th-century Scottish historians 19th-century novelists 19th-century philosophers 19th-century translators 19th-century Scottish novelists 19th-century Scottish philosophers Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Anti-Masonry Antisemitism in the United Kingdom Conservatism in the United Kingdom Critics of political economy Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Historians of the French Revolution Lecturers People associated with the National Portrait Gallery People educated at Annan Academy People from Dumfries and Galloway People of the Victorian era Proslavery activists Racism in the United Kingdom Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Rectors of the University of Edinburgh Right-wing politics in the United Kingdom Romantic critics of political economy Scottish biographers Scottish essayists 19th-century Scottish mathematicians Scottish literary critics Scottish monarchists Scottish novelists Scottish philosophers Scottish satirists Scottish social commentators Scottish translators Sexism in the United Kingdom Translators of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Writers of the Romantic era