Paul Painlevé on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

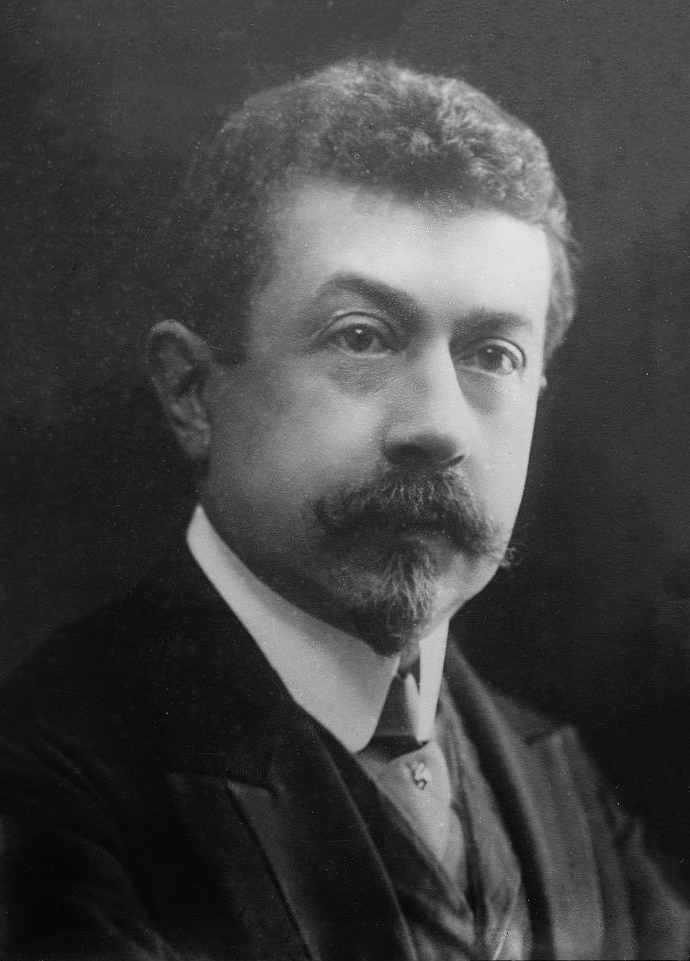

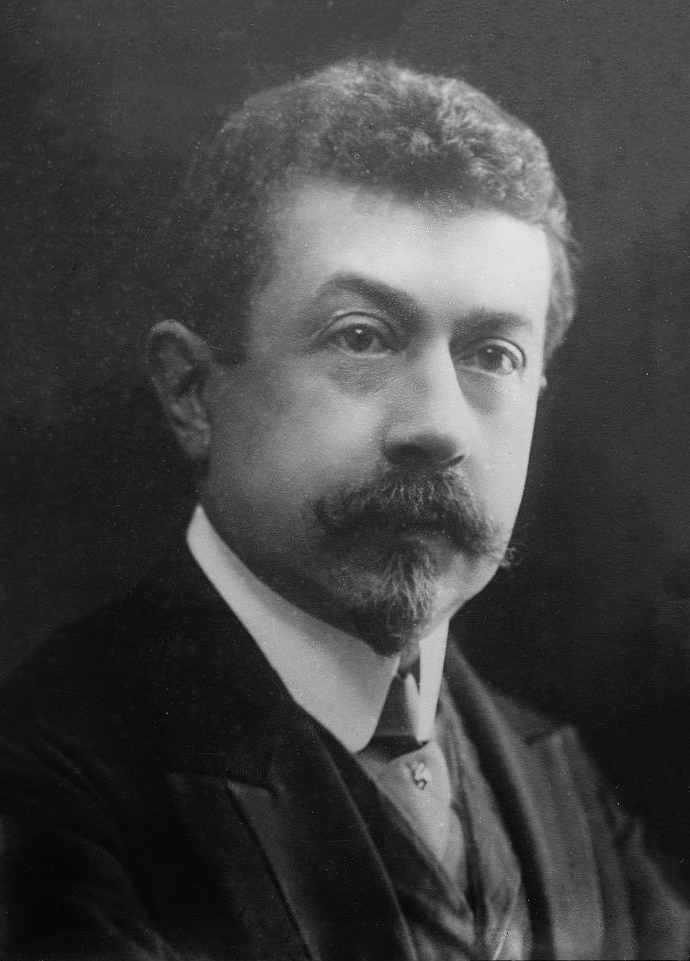

Paul Painlevé (; 5 December 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French mathematician and statesman. He served twice as

Some

Some

in ''

Following Painlevé's resignation, Briand formed a new government with Painlevé as Minister for War. Though Briand was defeated by

Following Painlevé's resignation, Briand formed a new government with Painlevé as Minister for War. Though Briand was defeated by

Biography (French)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Painleve, Paul 1863 births 1933 deaths Politicians from Paris Republican-Socialist Party politicians Prime Ministers of France French Ministers of War French Ministers of Finance Presidents of the Chamber of Deputies (France) Members of the 10th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 11th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 12th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 13th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 14th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 15th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic French mathematicians Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni École Normale Supérieure alumni Lille University of Science and Technology faculty Members of the Institute for Catalan Studies Members of the French Academy of Sciences French people of World War I Burials at the Panthéon, Paris Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

of the Third Republic: 12 September – 13 November 1917 and 17 April – 22 November 1925. His entry into politics came in 1906 after a professorship at the Sorbonne that began in 1892.

His first term as prime minister lasted only nine weeks but dealt with weighty issues, such as the Russian Revolution, the American entry into the war, the failure of the Nivelle Offensive

The Nivelle offensive (16 April – 9 May 1917) was a Franco-British operation on the Western Front in the First World War which was named after General Robert Nivelle, the commander-in-chief of the French metropolitan armies, who led the offensi ...

, quelling the French Army Mutinies

The 1917 French Army mutinies took place amongst French Army troops on the Western Front in Northern France during World War I. They started just after the unsuccessful and costly Second Battle of the Aisne, the main action in the Nivelle Offen ...

and relations with the British. In the 1920s as Minister of War he was a key figure in building the Maginot Line

The Maginot Line (french: Ligne Maginot, ), named after the Minister of the Armed Forces (France), French Minister of War André Maginot, is a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapon installations built by French Third Republic, F ...

. In his second term as prime minister he dealt with the outbreak of rebellion in Syria's Jabal Druze in July

1925 which had excited public and parliamentary anxiety over the general crisis of France's empire.

Biography

Early life

Painlevé was born in Paris. Brought up within a family of skilled artisans (his father was a draughtsman) Painlevé showed early promise across the range of elementary studies and was initially attracted by either an engineering or political career. However, he finally entered theÉcole Normale Supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, S ...

in 1883 to study mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, receiving his doctorate in 1887 following a period of study at Göttingen

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The ori ...

, Germany with Felix Klein

Christian Felix Klein (; 25 April 1849 – 22 June 1925) was a German mathematician and mathematics educator, known for his work with group theory, complex analysis, non-Euclidean geometry, and on the associations between geometry and grou ...

and Hermann Amandus Schwarz

Karl Hermann Amandus Schwarz (; 25 January 1843 – 30 November 1921) was a German mathematician, known for his work in complex analysis.

Life

Schwarz was born in Hermsdorf, Silesia (now Jerzmanowa, Poland). In 1868 he married Marie Kummer, ...

. Intending an academic career he became professor at Université de Lille, returning to Paris in 1892 to teach at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

, École Polytechnique

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

and later at the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris n ...

and the École Normale Supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, S ...

. He was elected a member of the Académie des Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at ...

in 1900.

He married Marguerite Petit de Villeneuve in 1901. Marguerite died during the birth of their son Jean Painlevé in the following year.

Painlevé's mathematical work on differential equation

In mathematics, a differential equation is an equation that relates one or more unknown functions and their derivatives. In applications, the functions generally represent physical quantities, the derivatives represent their rates of change, ...

s led him to encounter their application to the theory of flight and, as ever, his broad interest in engineering topics fostered an enthusiasm for the emerging field of aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes airplane, fixed-wing and helicopter, rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as aerostat, lighter- ...

. In 1908, he became Wilbur Wright's first airplane passenger in France and in 1909 created the first university course in aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identif ...

.

Mathematical work

Some

Some differential equation

In mathematics, a differential equation is an equation that relates one or more unknown functions and their derivatives. In applications, the functions generally represent physical quantities, the derivatives represent their rates of change, ...

s can be solved using elementary algebraic operations that involve the trigonometric

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

and exponential function

The exponential function is a mathematical function denoted by f(x)=\exp(x) or e^x (where the argument is written as an exponent). Unless otherwise specified, the term generally refers to the positive-valued function of a real variable, ...

s (sometimes called elementary function

In mathematics, an elementary function is a function of a single variable (typically real or complex) that is defined as taking sums, products, roots and compositions of finitely many polynomial, rational, trigonometric, hyperbolic, and ...

s). Many interesting special functions

Special functions are particular mathematical functions that have more or less established names and notations due to their importance in mathematical analysis, functional analysis, geometry, physics, or other applications.

The term is defined b ...

arise as solutions of linear second order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

ordinary differential equations

In mathematics, an ordinary differential equation (ODE) is a differential equation whose unknown(s) consists of one (or more) function(s) of one variable and involves the derivatives of those functions. The term ''ordinary'' is used in contrast ...

. Around the turn of the century,

Painlevé, É. Picard, and B. Gambier showed that

of the class of nonlinear

In mathematics and science, a nonlinear system is a system in which the change of the output is not proportional to the change of the input. Nonlinear problems are of interest to engineers, biologists, physicists, mathematicians, and many oth ...

second order ordinary differential equations with polynomial

In mathematics, a polynomial is an expression consisting of indeterminates (also called variables) and coefficients, that involves only the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and positive-integer powers of variables. An exampl ...

coefficients

In mathematics, a coefficient is a multiplicative factor in some term of a polynomial, a series, or an expression; it is usually a number, but may be any expression (including variables such as , and ). When the coefficients are themselves ...

, those that possess a certain desirable technical property, shared by the linear equations (nowadays commonly referred to as the ' Painlevé property') can always be transformed into one of fifty canonical forms. Of these fifty equations, just six require 'new' transcendental functions for their solution. These new transcendental functions, solving the remaining six equations, are called the Painlevé transcendents In mathematics, Painlevé transcendents are solutions to certain nonlinear second-order ordinary differential equations in the complex plane with the Painlevé property (the only movable singularities are poles), but which are not generally solvabl ...

, and interest in them has revived recently due to their appearance in modern geometry, integrable systems and statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. It does not assume or postulate any natural laws, but explains the macroscopic b ...

.

In 1895 he gave a series of lectures at Stockholm University

Stockholm University ( sv, Stockholms universitet) is a public research university in Stockholm, Sweden, founded as a college in 1878, with university status since 1960. With over 33,000 students at four different faculties: law, humanities, ...

on differential equations, at the end stating the Painlevé conjecture about singularities of the n-body problem

In physics, the -body problem is the problem of predicting the individual motions of a group of celestial objects interacting with each other gravitationally.Leimanis and Minorsky: Our interest is with Leimanis, who first discusses some histor ...

. In the same year he published work on the Painlevé paradox In rigid-body dynamics, the Painlevé paradox (also called frictional paroxysms by Jean Jacques Moreau) is the paradox that results from inconsistencies between the contact and Coulomb models of friction. It is named for former French prime minist ...

, an apparent contradiction in simple models of friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

.

In the 1920s, Painlevé briefly turned his attention to the new theory of gravitation, general relativity

General relativity, also known as the general theory of relativity and Einstein's theory of gravity, is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and is the current description of gravitation in modern physics ...

, which had recently been introduced by Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

. In 1921, Painlevé proposed the Gullstrand–Painlevé coordinates Gullstrand–Painlevé coordinates are a particular set of coordinates for the Schwarzschild metric – a solution to the Einstein field equations which describes a black hole. The ingoing coordinates are such that the time coordinate follows the pr ...

for the Schwarzschild metric

In Einstein's theory of general relativity, the Schwarzschild metric (also known as the Schwarzschild solution) is an

exact solution to the Einstein field equations that describes the gravitational field outside a spherical mass, on the assump ...

. The modification in the coordinate system was the first to reveal clearly that the Schwarzschild radius

The Schwarzschild radius or the gravitational radius is a physical parameter in the Schwarzschild solution to Einstein's field equations that corresponds to the radius defining the event horizon of a Schwarzschild black hole. It is a characteri ...

is a mere coordinate singularity A coordinate singularity occurs when an apparent singularity or discontinuity occurs in one coordinate frame that can be removed by choosing a different frame.

An example is the apparent (longitudinal) singularity at the 90 degree latitude in sph ...

(with however, profound global significance: it represents the event horizon

In astrophysics, an event horizon is a boundary beyond which events cannot affect an observer. Wolfgang Rindler coined the term in the 1950s.

In 1784, John Michell proposed that gravity can be strong enough in the vicinity of massive compact ob ...

of a black hole

A black hole is a region of spacetime where gravity is so strong that nothing, including light or other electromagnetic waves, has enough energy to escape it. The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass can def ...

). This essential point was not generally appreciated by physicists until around 1963. In his diary, Harry Graf Kessler

Harry Clemens Ulrich Graf von Kessler (23 May 1868 – 30 November 1937) was an Anglo-German count, diplomat, writer, and patron of modern art. English translations of his diaries "Journey to the Abyss" (2011) and "Berlin in Lights" (1971) rev ...

recorded that during a later visit to Berlin, Painlevé discussed pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campai ...

international politics

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such a ...

with Einstein, but there is no reference to discussions concerning the significance of the Schwarzschild radius.

Early political career

Between 1915 and 1917, Painlevé served as French Minister for Public Instruction and Inventions. In December 1915, he requested a scientific exchange agreement between France and Britain, resulting in Anglo-French collaboration that ultimately led to the parallel development byPaul Langevin

Paul Langevin (; ; 23 January 1872 – 19 December 1946) was a French physicist who developed Langevin dynamics and the Langevin equation. He was one of the founders of the ''Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes'', an ant ...

in France and Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders ...

in Britain of the first active sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect objects on o ...

.Michael A. Ainslie ''Principles of Sonar Performance Modelling'', Springer, 2010 , page 13

First period as French Prime Minister

Painlevé took his aviation interests, along with those in naval and military matters, with him when he became, in 1906, Deputy for Paris's 5th arrondissement, the so-calledLatin Quarter

The Latin Quarter of Paris (french: Quartier latin, ) is an area in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistro ...

. By 1910, he had vacated his academic posts and World War I led to his active participation in military committees, joining Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

's cabinet in 1915 as Minister for Public Instruction and Inventions.

On his appointment as War Minister in March 1917 he was immediately called upon to give his approval, albeit with some misgivings, to Robert Georges Nivelle

Robert Georges Nivelle (15 October 1856 – 22 March 1924) was a French artillery general officer who served in the Boxer Rebellion and the First World War. In May 1916, he succeeded Philippe Pétain as commander of the French Second Army in the ...

's wildly optimistic plans for a breakthrough offensive in Champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, ...

. Painlevé reacted to the disastrous public failure of the plan by dismissing Nivelle and controversially replacing him with Henri Philippe Pétain

Henri is an Estonian, Finnish, French, German and Luxembourgish form of the masculine given name Henry.

People with this given name

; French noblemen

:'' See the ' List of rulers named Henry' for Kings of France named Henri.''

* Henri I de Mon ...

."Paul Painlevé"in ''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' He was also responsible for isolating the Russian Expeditionary Force in France in the La Courtine camp, located in a remote spot on the plateau of Millevaches.

On 7 September 1917, Prime Minister Alexandre Ribot

Alexandre-Félix-Joseph Ribot (; 7 February 184213 January 1923) was a French politician, four times Prime Minister.

Early career

Ribot was born in Saint-Omer, Pas-de-Calais. After a brilliant academic career at the University of Paris, where h ...

lost the support of the Socialists and Painlevé was called upon to form a new government.

Painlevé was a leading voice at the Rapallo conference

The Rapallo conference (5 November 1917) and the Peschiera conference (8 November 1917) were meetings of the prime ministers of Italy, France and Britain—Vittorio Orlando, Paul Painlevé and David Lloyd George—during World War I in Rapallo a ...

that led to the establishment of the Supreme Allied Council, a consultative body of Allied powers that anticipated the unified Allied command finally established in the following year. He appointed Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Ar ...

as French representative knowing that he was the natural Allied commander. On Painlevé's return to Paris he was defeated and resigned on 13 November 1917 to be succeeded by Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

. Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Arto ...

was finally named Allied ''generalissimo'' in March 1918, eventually becoming commander-in-chief of all Allied armies on the Western and Italian fronts.

Second period as French Prime Minister

Painlevé then played little active role in politics until the election of November 1919 when he emerged as a leftist critic of the right-wing Bloc National. By the time the next election approached in May 1924 his collaboration withÉdouard Herriot

Édouard Marie Herriot (; 5 July 1872 – 26 March 1957) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic who served three times as Prime Minister (1924–1925; 1926; 1932) and twice as President of the Chamber of Deputies. He led the f ...

, a fellow member of Briand's 1915 cabinet, had led to the formation of the Cartel des Gauches

The Cartel of the Left (french: Cartel des gauches, ) was the name of the governmental alliance between the Radical-Socialist Party, the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), and other smaller left-republican parties that ...

. Winning the election, Herriot became Prime Minister in June, while Painlevé became President of the Chamber of Deputies. Though Painlevé ran for President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

in 1924 he was defeated by Gaston Doumergue

Pierre Paul Henri Gaston Doumergue (; 1 August 1863 in Aigues-Vives, Gard18 June 1937 in Aigues-Vives) was a French politician of the Third Republic. He served as President of France from 13 June 1924 to 13 June 1931.

Biography

Doumergue cam ...

. Herriot's administration publicly recognised the Soviet Union, accepted the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

and agreed to evacuate the Ruhr. However, a financial crisis arose from the ensuing devaluation of the franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

and in April 1925, Herriot fell and Painlevé became Prime Minister for a second time on 17 April. Unfortunately, he was unable to offer convincing remedies for the financial problems and was forced to resign on 21 November.

Later political career

Following Painlevé's resignation, Briand formed a new government with Painlevé as Minister for War. Though Briand was defeated by

Following Painlevé's resignation, Briand formed a new government with Painlevé as Minister for War. Though Briand was defeated by Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (, ; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France.

Trained in law, Poincaré was elected deputy in ...

in 1926, Painlevé continued in office. Poincaré stabilised the franc with a return to the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

, but ultimately acceded power to Briand. During his tenure as Minister of War, Painlevé was instrumental in the creation of the Maginot Line

The Maginot Line (french: Ligne Maginot, ), named after the Minister of the Armed Forces (France), French Minister of War André Maginot, is a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapon installations built by French Third Republic, F ...

. This line of military fortifications along France's Eastern border was largely designed by Painlevé, yet named for André Maginot, owing to Maginot's championing of public support and funding. Painlevé remained in office as Minister for War until July 1929.

From 1925 to 1933, Painlevé represented France in the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

(he replaced Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopherHenri Bergson. 2014. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 August 2014, from https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/61856/Henri-Bergson Le Roy, ...

and was himself replaced by Édouard Herriot

Édouard Marie Herriot (; 5 July 1872 – 26 March 1957) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic who served three times as Prime Minister (1924–1925; 1926; 1932) and twice as President of the Chamber of Deputies. He led the f ...

).

Though he was proposed for President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

in 1932, Painlevé withdrew before the election. He became Minister of Air later that year, making proposals for an international treaty to ban the manufacture of bomber aircraft and to establish an international air force to enforce global peace. On the fall of the government in January 1933, his political career ended.

Painlevé died in Paris in October of the same year. On 4 November, after a eulogy by Prime Minister Albert Sarraut

Albert-Pierre Sarraut (; 28 July 1872 – 26 November 1962) was a French Radical politician, twice Prime Minister during the Third Republic.

Biography

Sarraut was born on 28 July 1872 in Bordeaux, Gironde, France.

On 14 March 1907 Sarraut, ...

, he was interred in the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was b ...

.

Honours

*The aircraft carrier '' Painlevé'' was named in his honour. *The asteroid 953 Painleva was named in his honour. *The Laboratoire Paul Painlevé ( fr), a French mathematics research lab, is named in his honour. *Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

dedicated the second of his '' Trois Chansons'' to him in 1915.

Composition of governments

Painlevé's First Government, 12 September – 16 November 1917

*Paul Painlevé – President of the Council and Minister of War *Alexandre Ribot

Alexandre-Félix-Joseph Ribot (; 7 February 184213 January 1923) was a French politician, four times Prime Minister.

Early career

Ribot was born in Saint-Omer, Pas-de-Calais. After a brilliant academic career at the University of Paris, where h ...

– Minister of Foreign Affairs

*Louis Loucheur

Louis Loucheur (12 August 1872 in Roubaix, Nord – 22 November 1931 in Paris) was a French politician in the Third Republic, at first a member of the conservative Republican Federation, then of the Democratic Republican Alliance and of the Ind ...

– Minister of Armaments and War Manufacturing

* Théodore Steeg – Minister of the Interior

* Louis Lucien Klotz – Minister of Finance

*André Renard

André Renard (25 May 191120 July 1962) was a Belgian trade union leader who, in the aftermath of World War II, became an influential figure within the Walloon Movement.

Born into a working-class family, Renard was as a metalworker in the L ...

– Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

* Raoul Péret – Minister of Justice

* Charles Chaumet – Minister of Marine

* Charles Daniel-Vincent – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

*Fernand David

Fernand David (18 October 1869, Annemasse, Haute-Savoie

Haute-Savoie (; Arpitan: ''Savouè d'Amont'' or ''Hiôta-Savouè''; en, Upper Savoy) or '; it, Alta Savoia. is a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of Southeastern France, b ...

– Minister of Agriculture

* Maurice Long – Minister of General Supply

*René Besnard

René Henry Besnard (12 April 1879 – 12 March 1952) was a French politician who was a deputy for Indre-et-Loire from 1906 to 1919 and senator from 1920 to 1941.

He was briefly Minister of the Colonies and then Minister of Labor and Social Welf ...

– Minister of Colonies

* Albert Claveille – Minister of Public Works and Transport

*Étienne Clémentel

Étienne Clémentel (11 January 1864 – 25 December 1936) was a French politician. He served as a member of the National Assembly of France from 1900 to 1919 and as French Senator from 1920 to 1936. He also served as Minister of Colonies from 2 ...

– Minister of Commerce, Industry, Posts, and Telegraphs

*Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the introduction (in Jul ...

– Minister of State

*Léon Bourgeois

Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois (; 21 May 185129 September 1925) was a French statesman. His ideas influenced the Radical Party regarding a wide range of issues. He promoted progressive taxation such as progressive income taxes and social insu ...

– Minister of State

* Paul Doumer – Minister of State

* Jean Dupuy – Minister of State

Changes

*27 September 1917 – Henry Franklin-Bouillon

Henry Franklin-Bouillon (3 September 1870 - 12 September 1937) was a French politician.

Franklin-Bouillon was born in Jersey. He began as a member of the Radical-Socialist Party, but belonged to its furthest right-wing: he advocated that the ...

entered the ministry as Minister of State.

*23 October 1917 – Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the introduction (in Jul ...

succeeded Ribot as Minister of Foreign Affairs

Painlevé's Second Ministry, 17 April – 29 October 1925

*Paul Painlevé – President of the Council and Minister of War *Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

– Minister of Foreign Affairs

*Abraham Schrameck

Abraham Schrameck (26 November 1867 – 19 October 1948) was a French-Jewish politician, Member of the Senate (France), senator, Minister of the Interior (France), Minister of the Interior, and colonial governor of French Madagascar.

Early life ...

– Minister of the Interior

*Joseph Caillaux

Joseph-Marie–Auguste Caillaux (; 30 March 1863 Le Mans – 22 November 1944 Mamers) was a French politician of the Third Republic. He was a leader of the French Radical Party and Minister of Finance, but his progressive views in opposition ...

– Minister of Finance

* Antoine Durafour – Minister of Labour, Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

* Théodore Steeg – Minister of Justice

*Émile Borel

Félix Édouard Justin Émile Borel (; 7 January 1871 – 3 February 1956) was a French mathematician and politician. As a mathematician, he was known for his founding work in the areas of measure theory and probability.

Biography

Borel was ...

– Minister of Marine

* Anatole de Monzie – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts.

* Louis Antériou – Minister of Pensions

*Jean Durand

Jean Durand (1882–1946) was a French screenwriter and film director of the silent era.Rège p.349 He was extremely prolific, working on well over two hundred films. He was married to the actress Berthe Dagmar.

Selected filmography

* ''Tarnished ...

– Minister of Agriculture

* Orly André-Hesse – Minister of Colonies

*Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occ ...

– Minister of Public Works

* Charles Chaumet – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Changes

*11 October 1925 – Anatole de Monzie succeeded Steeg as Minister of Justice. Yvon Delbos succeeded Monzie as Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts.

Painlevé's Third Ministry, 29 October – 28 November 1925

*Paul Painlevé – President of the Council and Minister of Finance *Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

– Minister of Foreign Affairs

*Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, and the Prime Minister of France who signed the Munich Agreement before the outbreak of World War II.

Daladier was born in Carpe ...

– Minister of War

*Abraham Schrameck

Abraham Schrameck (26 November 1867 – 19 October 1948) was a French-Jewish politician, Member of the Senate (France), senator, Minister of the Interior (France), Minister of the Interior, and colonial governor of French Madagascar.

Early life ...

– Minister of the Interior

*Georges Bonnet

Georges-Étienne Bonnet (22/23 July 1889 – 18 June 1973) was a French politician who served as foreign minister in 1938 and 1939 and was a leading figure in the Radical Party.

Early life

Bonnet was born in Bassillac, Dordogne, the son of ...

– Minister of Budget

* Antoine Durafour – Minister of Labour, Hygiene, Welfare Work, and Social Security Provisions

*Camille Chautemps

Camille Chautemps (1 February 1885 – 1 July 1963) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic, three times President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister).

He was the father-in-law of U.S. politician and statesman Howard J ...

– Minister of Justice

*Émile Borel

Félix Édouard Justin Émile Borel (; 7 January 1871 – 3 February 1956) was a French mathematician and politician. As a mathematician, he was known for his founding work in the areas of measure theory and probability.

Biography

Borel was ...

– Minister of Marine

* Yvon Delbos – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

* Louis Antériou – Minister of Pensions

*Jean Durand

Jean Durand (1882–1946) was a French screenwriter and film director of the silent era.Rège p.349 He was extremely prolific, working on well over two hundred films. He was married to the actress Berthe Dagmar.

Selected filmography

* ''Tarnished ...

– Minister of Agriculture

*Léon Perrier

Léon Perrier (1873–1948) was a French politician. He served as the French Minister of the Colonies from 1925 to 1928.

Early life

Léon Perrier was born on 1 February 1873 in Tournon-sur-Rhône in the Ardèche, France.

Career

Perrier served as ...

– Minister of Colonies

* Anatole de Monazie – Minister of Public Works

* Charles Daniel-Vincent – Minister of Commerce and Industry

Works

* ''Sur les lignes singulières des fonctions analytiques'' - 1887/''On singular lines of analytic functions''. * ''Mémoire sur les équations différentielles du premier ordre'' - 1892/''Memory on first order differential equations''. * ''Leçons sur la théorie analytique des équations différentielles'', A. Hermann (Paris), 1897/''A course on analytic theory of differential equations''. * ''Leçons sur les fonctions de variables réelles et les développements en séries de polynômes'' - 1905/''A course on real variable functions and polynomial development series''. * ''Cours de mécanique et machines'' (Paris), 1907/''A course on mechanics and machines''. * ''Cours de mécanique et machines 2'' (Paris), 1908/''A course on mechanics and machines 2''. * ''Leçons sur les fonctions définies par les équations différentielles du premier ordre'', Gauthier-Villars (Paris), 1908/''A course on functions defined by first order differential equations''. * ''L'aéroplane'', Lille, 1909/''Aeroplane''. * ''Cours de mécanique et machines'' (Paris), 1909/''A course on mechanics and machines''. * ''L'aviation'', Paris, Felix Alcan, 1910/''Aviation''. * ''Les axiomes de la mécanique, examen critique'' ; ''Note sur la propagation de la lumière'' - 1922/''Mechanics axioms, a critical study'' ; ''Notes on light spread''. * ''Leçons sur la théorie analytique des équations différentielles'', Hermann, Paris, 1897/''A course on analytical theory of differential equations''. * ''Trois mémoires de Painlevé sur la relativité'' (1921-1922)/''Painlevé's three memories on relativity''.See also

* List of people on the cover of Time Magazine: 1920sReferences

Further reading

* *External links

*Biography (French)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Painleve, Paul 1863 births 1933 deaths Politicians from Paris Republican-Socialist Party politicians Prime Ministers of France French Ministers of War French Ministers of Finance Presidents of the Chamber of Deputies (France) Members of the 10th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 11th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 12th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 13th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 14th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 15th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic French mathematicians Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni École Normale Supérieure alumni Lille University of Science and Technology faculty Members of the Institute for Catalan Studies Members of the French Academy of Sciences French people of World War I Burials at the Panthéon, Paris Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles