Constantine V on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Constantine V (; July 718 – 14 September 775) was

Like his father Leo III, Constantine supported

Like his father Leo III, Constantine supported

Assiduous in courting popularity, Constantine consciously employed the

Assiduous in courting popularity, Constantine consciously employed the

Constantine V was a highly capable ruler, continuing the reformsfiscal, administrative and militaryof his father. He was also a successful general, not only consolidating the empire's borders, but actively campaigning beyond those borders, both east and west. At the end of his reign the empire had strong finances, a capable army that was proud of its successes and a church that appeared to be subservient to the political establishment.

In concentrating on the security of the empire's core territories he tacitly abandoned some peripheral regions, notably in Italy, which were lost. However, the hostile reaction of the Roman Church and the Italian people to iconoclasm had probably doomed imperial influence in central Italy, regardless of any possible military intervention. Due to his espousal of iconoclasm Constantine was damned in the eyes of contemporary iconodule writers and subsequent generations of Orthodox historians. Typical of this demonisation are the descriptions of Constantine in the writings of Theophanes the Confessor: "a monster athirst for blood", "a ferocious beast", "unclean and bloodstained magician taking pleasure in evoking demons", "a precursor of

Constantine V was a highly capable ruler, continuing the reformsfiscal, administrative and militaryof his father. He was also a successful general, not only consolidating the empire's borders, but actively campaigning beyond those borders, both east and west. At the end of his reign the empire had strong finances, a capable army that was proud of its successes and a church that appeared to be subservient to the political establishment.

In concentrating on the security of the empire's core territories he tacitly abandoned some peripheral regions, notably in Italy, which were lost. However, the hostile reaction of the Roman Church and the Italian people to iconoclasm had probably doomed imperial influence in central Italy, regardless of any possible military intervention. Due to his espousal of iconoclasm Constantine was damned in the eyes of contemporary iconodule writers and subsequent generations of Orthodox historians. Typical of this demonisation are the descriptions of Constantine in the writings of Theophanes the Confessor: "a monster athirst for blood", "a ferocious beast", "unclean and bloodstained magician taking pleasure in evoking demons", "a precursor of

By his first wife, Tzitzak ("Irene of Khazaria"), Constantine V had one son:

* Leo IV, who succeeded as emperor. He was crowned in 751.

By his second wife, Maria, Constantine V is not known to have had children.

By his third wife, Eudokia, Constantine V had five sons and a daughter:

* Christopher, ''caesar''

* Nikephoros, ''caesar''

* Niketas, '' nobelissimos''

* Eudokimos, ''nobelissimos''

* Anthimos, ''nobelissimos''

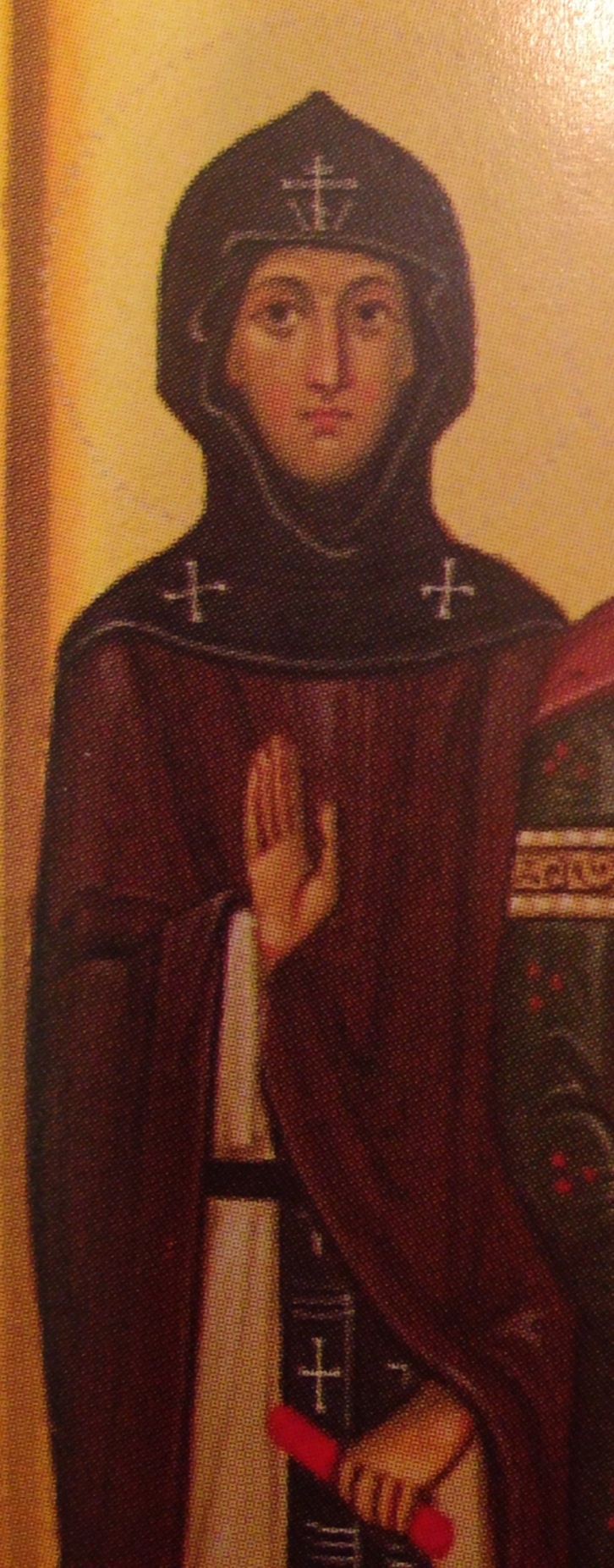

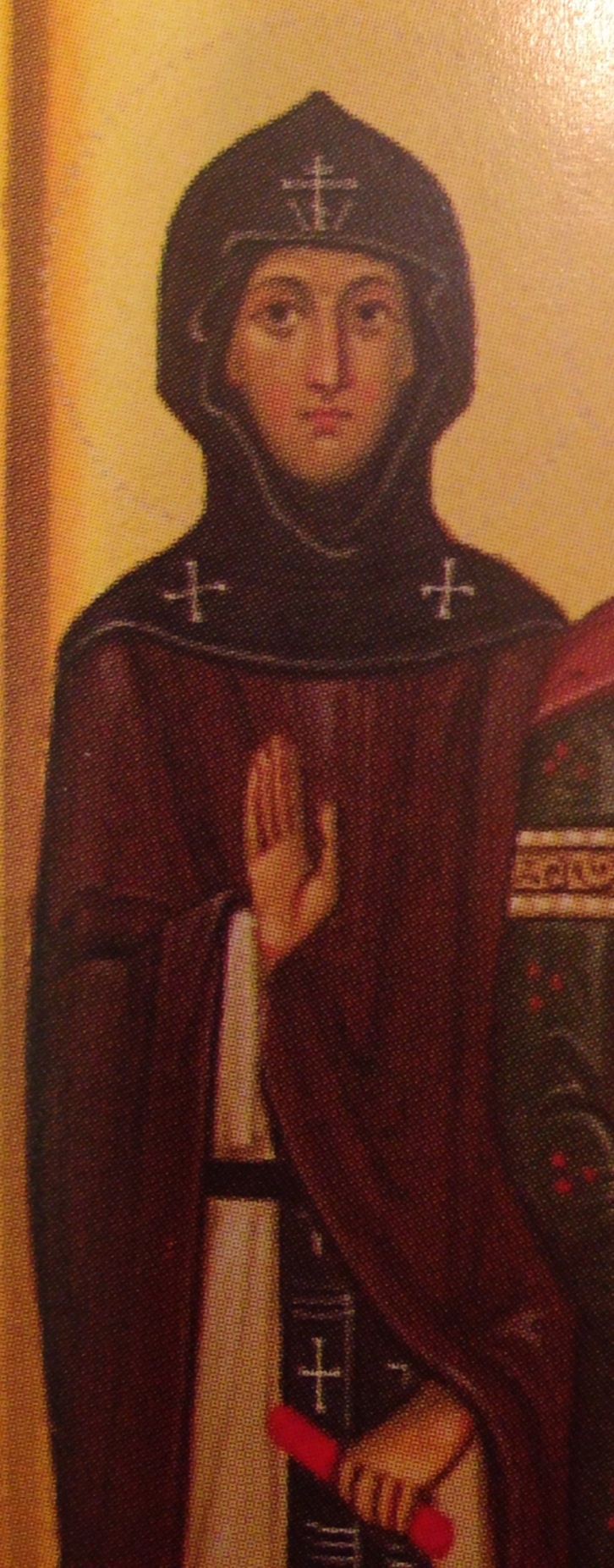

* Anthousa (an iconodule, after her father's death she became a nun, she was later venerated as Saint Anthousa the YoungerConstas, pp. 21–24

By his first wife, Tzitzak ("Irene of Khazaria"), Constantine V had one son:

* Leo IV, who succeeded as emperor. He was crowned in 751.

By his second wife, Maria, Constantine V is not known to have had children.

By his third wife, Eudokia, Constantine V had five sons and a daughter:

* Christopher, ''caesar''

* Nikephoros, ''caesar''

* Niketas, '' nobelissimos''

* Eudokimos, ''nobelissimos''

* Anthimos, ''nobelissimos''

* Anthousa (an iconodule, after her father's death she became a nun, she was later venerated as Saint Anthousa the YoungerConstas, pp. 21–24

JSTOR

* Jeffreys, E., Haldon, J.F. and Cormack, R. (eds.) (2008) ''The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies'', Oxford University Press, * Jenkins, R. J. H. (1966) ''Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries, AD 610–1071'', Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London * * Loos, M. (1974) ''Dualist Heresy in the Middle Ages'', Martinus Nijhoff NV, The Hague * * Magdalino, P. (2015) "The People and the Palace", in ''The Emperor's House: Palaces from Augustus to the Age of Absolutism'', Featherstone, M., Spieser, J-M., Tanman, G. and Wulf-Rheidt, U. (eds.), Walter de Gruyter, Göttingen * * Ostrogorsky, G. (1980) ''History of the Byzantine State'', Basil Blackwell, Oxford * Pelikan, J. (1977) ''The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 2: The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600–1700)'', University of Chicago Press, Chicago * Robertson, A. (2017) "The Orient Express: Abbot John's Rapid trip from Constantinople to Ravenna c. AD 700", in ''Byzantine Culture in Translation'', Brown, B. and Neil, B. (eds.), Brill, Leiden * Rochow, I. (1994) ''Kaiser Konstantin V. (741–775). Materialien zu seinem Leben und Nachleben'' (in German), Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, Germany * * Treadgold, W. T. (1995) ''Byzantium and Its Army'', Stanford University Press, Stanford, California * * Treadgold, W. T. (2012) "Opposition to Iconoclasm as Grounds for Civil War", in ''Byzantine War Ideology Between Roman Imperial Concept And Christian Religion'', Koder, J. and Stouratis, I. (eds.), Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, Vienna

JSTOR

* Zuckerman, C. (1988) ''The Reign of Constantine V in the Miracles of St. Theodore the Recruit'', ''Revue des Études Byzantines'', ''tome'' 46, pp. 191–210, ''Institut Français D'Études Byzantines'', Paris,

Byzantine emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

from 741 to 775. His reign saw a consolidation of Byzantine security from external threats. As an able military leader, Constantine took advantage of civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

in the Muslim world to make limited offensives on the Arab frontier. With this eastern frontier secure, he undertook repeated campaigns against the Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic peoples, Turkic Nomad, semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region between the 5th and 7th centu ...

in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. His military activity, and policy of settling Christian populations from the Arab frontier in Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

, made Byzantium's hold on its Balkan territories more secure. He was also responsible for important military and administrative innovations and reforms.

Religious strife and controversy was a prominent feature of his reign. His fervent support of iconoclasm

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

and opposition to monasticism

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Chr ...

led to his vilification by some contemporary commentators and the majority of later Byzantine writers, who denigrated him with the nicknames "Dung-Named" (), because he allegedly defaecated during his baptism, similarly "Anointed with Urine" (), and "the Equestrian" (), referencing the excrement of horses.

Early life

Constantine was born inConstantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, the son and successor of Emperor Leo III and his wife Maria. In the Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

of 720, at two years of age, he was associated with his father on the throne, and crowned co-emperor by Patriarch Germanus I. In Byzantine political theory more than one emperor could share the throne; however, although all were accorded the same ceremonial status, only one emperor wielded ultimate power. As the position of emperor was in theory, and sometimes in practise, elective rather than strictly hereditary, a ruling emperor would often associate a son or other chosen successor with himself as a co-emperor to ensure the eventual succession. To celebrate the coronation of his son, Leo III introduced a new silver coin, the '' miliaresion''; worth one-twelfth of a gold ''nomisma

''Nomisma'' () was the ancient Greek word for "money" and is derived from nomos () meaning "'anything assigned,' 'a usage,' 'custom,' 'law,' 'ordinance,' or 'that which is a habitual practice.'"The King James Version New Testament Greek Lexicon; ...

'', it soon became an integral part of the Byzantine economy. In 726, Constantine's father issued the '' Ecloga''; a revised legal code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the co ...

, it was attributed to both father and son jointly. Constantine married Tzitzak, daughter of the Khazar

The Khazars ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a nomadic Turkic people who, in the late 6th century CE, established a major commercial empire covering the southeastern section of modern European Russia, southern Ukraine, Crimea, an ...

khagan Bihar

Bihar ( ) is a states and union territories of India, state in Eastern India. It is the list of states and union territories of India by population, second largest state by population, the List of states and union territories of India by are ...

, an important Byzantine ally. His new bride was baptized Irene (''Eirēnē'', "peace") in 732. On his father's death, Constantine succeeded as sole emperor on 18 June 741.

Historical accounts of Constantine make reference to a chronic medical condition, possibly epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of Non-communicable disease, non-communicable Neurological disorder, neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked Seizure, seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activit ...

or leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a Chronic condition, long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the Peripheral nervous system, nerves, respir ...

; early in his reign this may have been employed by those rebelling against him to question his fitness to be emperor.

Reign

Rebellion of Artabasdos

Immediately after Constantine's accession in 741, his brother-in-law Artabasdos, husband of his older sister, Anna, rebelled. Artabasdos was thestrategos

''Strategos'' (), also known by its Linguistic Latinisation, Latinized form ''strategus'', is a Greek language, Greek term to mean 'military General officer, general'. In the Hellenistic world and in the Byzantine Empire, the term was also use ...

(military governor) of the Opsikion ''theme'' (province) and had effective control of the Armeniac theme. The event is sometimes dated to 742, but this has been shown to be wrong.

Artabasdos struck against Constantine when their respective troops combined for an intended campaign against the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

; a trusted member of Constantine's retinue, called Beser, was killed in the attack. Constantine escaped and sought refuge in Amorion, where he was welcomed by the local soldiers, who had been commanded by Leo III before he became emperor. Meanwhile, Artabasdos advanced on Constantinople and, with the support of Theophanes Monutes (Constantine's regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

) and Patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Roman Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and ...

Anastasius, was acclaimed and crowned emperor. Constantine received the support of the Anatolic and Thracesian themes; Artabasdos secured the support of the theme of Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

in addition to his own Opsikion and Armeniac soldiers.

The rival emperors bided their time making military preparations. Artabasdos marched against Constantine at Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

in May 743 but was defeated. Three months later Constantine defeated Artabasdos' son Niketas and his Armeniac troops at Modrina and headed for Constantinople. In early November Constantine entered the capital, following a siege and a further battle. He immediately targeted his opponents, having many blinded or executed. Patriarch Anastasius was paraded on the back of an ass around the hippodrome

Hippodrome is a term sometimes used for public entertainment venues of various types. A modern example is the Hippodrome which opened in London in 1900 "combining circus, hippodrome, and stage performances".

The term hippodroming refers to fr ...

to the jeers of the Constantinopolitan mob, though he was subsequently allowed to stay in office. Artabasdos, having fled the capital, was apprehended at the fortress of Pouzanes in Anatolia, probably located to the south of Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; , ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocletian who rul ...

. Artabasdos and his sons were then publicly blinded and secured in the monastery of Chora on the outskirts of Constantinople.

Constantine's support of iconoclasm

Like his father Leo III, Constantine supported

Like his father Leo III, Constantine supported iconoclasm

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

, which was a theological movement that rejected the veneration of religious images and sought to destroy those in existence. Iconoclasm was later definitively classed as heretical. Constantine's avowed enemies in what was a bitter and long-lived religious dispute were the iconodules, who defended the veneration of images. Iconodule writers applied to Constantine the derogatory epithet ('dung-named', from , meaning 'faeces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

' or 'animal dung', and 'name'). Using this obscene name, they spread the rumour that as an infant he had defiled his own baptism by defaecating in the font, or on the imperial purple cloth with which he was swaddled.

Constantine questioned the legitimacy of any representation of God or Christ. The Church Father

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

John of Damascus made use of the term 'uncircumscribable' in relation to the depiction of God. Constantine, relying on the linguistic connection between 'uncircumscribed' and 'incapable of being depicted', argued that the uncircumscribable cannot be legitimately depicted in an image. As Christian theology holds that Christ is God, he also cannot be represented in an image. The Emperor was personally active in the theological debate; evidence exists for him composing thirteen treatises, two of which survive in fragmentary form. He also presented his religious views at meetings organised throughout the empire, sending representatives to argue his case. In February 754, Constantine convened a council at Hieria, which was attended entirely by iconoclast bishops. The council agreed with Constantine's religious policy on images, declaring them anathema

The word anathema has two main meanings. One is to describe that something or someone is being hated or avoided. The other refers to a formal excommunication by a Christian denomination, church. These meanings come from the New Testament, where a ...

, and it secured the election of a new iconoclast patriarch. However, it refused to endorse all of Constantine's policies, which were influenced by the more extremist iconoclasts and were possibly critical of the veneration of Mary, mother of Jesus

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

, and of the saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

s. The council confirmed the status of Mary as ''Theotokos

''Theotokos'' ( Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are or (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are "Mother of God" or "God-beare ...

'' (), or 'Mother of God', upheld the use of the terms "saint" and "holy" as legitimate, and condemned the desecration, burning, or looting of churches in the quest to suppress icon veneration.

The Council of Hieria was followed by a campaign to remove images from the walls of churches and to purge the court and bureaucracy of iconodules, however, the accounts of these events were written much later than they actually occurred, and by often vehemently anti-iconoclast sources, therefore their reliability is questionable. Since monasteries tended to be strongholds of iconophile sentiment and contributed little or nothing towards the secular needs of the state, Constantine specifically targeted these communities. He also expropriated monastic property for the benefit of the state or the army. These acts of repression against the monks were largely led by the Emperor's general Michael Lachanodrakon, who threatened resistant monks with blinding and exile. Constantine organised numerous pairs of monks and nuns to be paraded in the hippodrome, publicly ridiculing their vows of chastity. According to Theophanes the Confessor, the iconodule abbot Stephen the Younger, was beaten to death by a mob at the behest of the authorities. However even his hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian ...

, the ''Life of St. Stephen the Younger'', connects his execution more to treason against the Emperor, and indeed his punishments reflect those typically associated with an enemy of the state. Stephen was said to have trampled on a coin depicting the Emperor in order to provoke imperial retaliation and reveal the iconoclast hypocrisy of denying the force of sacred portraits but not of imperial portraits on coins. As a result of persecution, many monks fled to southern Italy and Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. The implacable resistance of iconodule monks and their supporters led to their propaganda reaching those close to the Emperor. On becoming aware of an iconodule-influenced conspiracy directed at himself, Constantine reacted uncompromisingly; in 765, eighteen high dignitaries charged with treason were paraded in the hippodrome, then variously executed, blinded or exiled. Patriarch Constantine II of Constantinople was implicated and deposed from office, and the following year he was tortured and beheaded.

According to later iconodule sources, for example Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople's ''Second Antirrheticus'' and treatise ''Against Constantinus Caballinus'', Constantine's iconoclasm had gone as far as to brand prayers to Mary and saints as heretical, or at least highly questionable. However, the extent of coherent official campaigns to forcibly destroy or cover up religious images or the existence of widespread government-sanctioned destruction of relics has been questioned by more recent scholarship. There is no evidence, for example, that Constantine formally banned the cult of saints. Pre-iconoclastic religious images did survive, and various existing accounts record that icons were preserved by being hidden. In general, the culture of pictorial religious representation appears to have survived the iconoclast period largely intact. The extent and severity of iconoclastic destruction of images and relics was exaggerated in later iconodule writings.

Scholars generally take the anathemas in the Council of Hieria condemning the one who "does not ask for he prayers of Mary and the saintsas having the freedom to intercede on behalf of the world according to the tradition of the church", as proof that Constantine never rejected the intercession of Mary and the saints, since they consider it inconceivable for an emperor to contradict the decisions of a council he convened. Moreover, the positive evidence that he rejected intercession is regarded as unreliable due to the iconodule motivation of its authors. Dissenting scholars point to the wealth of evidence, not only from Patriarch Nikephoros but from Theophanes and Patriarch Methodios I of Constantinople (847), who in his ''Life of Theophanes'' defends the intercession of saints, perpetuating a centuries-long controversy regarding the doctrine of soul-sleep, which if true would mean dead saints are incapable of intercession. They allege that it is conceivable that, although the moderate iconoclast party won at Hieria, which still affirmed the intercession of the saints, the radical iconoclasts who denied it briefly triumphed afterwards, with Constantine publicly interfering with religious practice by removing intercessory prayers to saints from church hymns and hagiographies, as described by the iconodule primary sources.

Iconodules considered Constantine's death a divine punishment. In the 9th century, following the ultimate triumph of the iconodules, Constantine's remains were removed from the imperial sepulchre in the Church of the Holy Apostles

The Church of the Holy Apostles (, ''Agioi Apostoloi''; ), also known as the Imperial Polyandrion (imperial cemetery), was a Byzantine Eastern Orthodox church in Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The first structure dated to ...

.

Domestic policies and administration

hippodrome

Hippodrome is a term sometimes used for public entertainment venues of various types. A modern example is the Hippodrome which opened in London in 1900 "combining circus, hippodrome, and stage performances".

The term hippodroming refers to fr ...

, scene of the ever-popular chariot races, to influence the populace of Constantinople. In this he made use of the 'circus factions', which controlled the competing teams of charioteers and their supporters, had widespread social influence, and could mobilise large numbers of the citizenry. The hippodrome became the setting of rituals of humiliation for war captives and political enemies, in which the mob took delight. Constantine's sources of support were the people and the army, and he used them against his iconodule opponents in the monasteries and in the bureaucracy of the capital. Iconoclasm was not purely an imperial religious conviction, it also had considerable popular support: some of Constantine's actions against the iconodules may have been motivated by a desire to retain the approval of the people and the army. The monasteries were exempt from taxation and monks from service in the army; the Emperor's antipathy towards them may have derived to a greater extent from secular, fiscal and manpower, considerations than from a reaction to their theology.

Constantine carried forward the administrative and fiscal reforms initiated by his father Leo III. The military governors (, ) were powerful figures, whose access to the resources of their extensive provinces often provided the means of rebellion. The Opsikion theme had been the power-base that enabled the rebellion of Artabasdos, and was also the theme situated nearest to the capital within Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. Constantine reduced the size of this theme, dividing from it the Bucellarian and, perhaps, the Optimaton themes. In those provinces closest to the seat of government this measure increased the number of ''stratēgoi'' and diminished the resources available to any single one, making rebellion less easy to accomplish.

Constantine was responsible for the creation of a small central army of fully professional soldiers, the imperial '' tagmata'' ('the regiments'). He achieved this by training for serious warfare a corps of largely ceremonial guards units that were attached to the imperial palace, and expanding their numbers. This force was designed to form the core of field armies and was composed of better-drilled, better-paid, and better-equipped soldiers than were found in the provincial '' themata'' units, whose troops were part-time soldier-farmers. Before their expansion, the vestigial Scholae and the other guards units presumably contained few useful soldiers, therefore Constantine must have incorporated former thematic soldiers into his new formation. Being largely based at or near the capital, the ''tagmata'' were under the immediate control of the Emperor and were free of the regional loyalties that had been behind so many military rebellions.

The fiscal administration of Constantine was highly competent. This drew from his enemies accusations of being a merciless and rapacious extractor of taxes and an oppressor of the rural population. However, the empire was prosperous and Constantine left a very well-stocked treasury for his successor. The area of cultivated land within the Empire was extended and food became cheaper; between 718 and c. 800 the corn (wheat) production of Thrace trebled. Constantine's court was opulent, with splendid buildings, and he consciously promoted the patronage of secular art to replace the religious art that he removed.

Constantine constructed a number of notable buildings in the Great Palace of Constantinople

The Great Palace of Constantinople (, ''Méga Palátion''; ), also known as the Sacred Palace (, ''Hieròn Palátion''; ), was the large imperial Byzantine palace complex located in the south-eastern end of the peninsula today making up the Fati ...

, including the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos and the ''porphyra''. The ''porphyra'' was a chamber lined with porphyry, a stone of imperial purple colour. In it expectant empresses underwent the final stages of labour and it was the birthplace of the children of reigning emperors. Constantine's son Leo was the first child born here, and thereby obtained the title ''porphyrogénnētos'' ( born in the purple) the ultimate accolade of legitimacy for an imperial prince or princess. The concept of a 'purple birth' predated the construction of the chamber, but it gained a literal aspect from the chamber's existence. The porphyry was reputed to have come from Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and represented a direct link to the ancient origins of Byzantine imperial authority. Constantine also rebuilt the prominent church of Hagia Eirene in Constantinople, which had been badly damaged by the earthquake that hit Constantinople in 740. The building preserves rare examples of iconoclastic church decoration.

With the impetus of having fathered numerous offspring, Constantine codified the court titles given to members of the imperial family. He associated only his eldest son, Leo, with the throne as co-emperor (in 751), but gave his younger sons the titles of caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war. He ...

for the more senior in age and nobelissimos for the more junior.

Campaigns against the Arabs

In 746, profiting by the unstable conditions in the Umayyad Caliphate, which was falling apart underMarwan II

Marwan ibn Muhammad ibn Marwan (; – 6 August 750), commonly known as Marwan II, was the fourteenth and last caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 744 until his death. His reign was dominated by a Third Fitna, civil war, and he was the l ...

, Constantine invaded Syria, captured Germanikeia (his father's birthplace) and recaptured the island of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. He organised the resettlement of part of the local Christian population to imperial territory in Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

, strengthening the empire's control of this region. In 747 his fleet destroyed the Arab fleet off Cyprus. The same year saw a serious outbreak of plague in Constantinople, which caused a pause in Byzantine military operations. Constantine retired to Bithynia

Bithynia (; ) was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Paphlagonia to the northeast a ...

to avoid the disease and, after it had run its course, resettled people from mainland Greece and the Aegean islands in Constantinople to replace those who had perished.

In 751 he led an invasion into the new Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes ...

under As-Saffah. Constantine captured Theodosiopolis and Melitene, which he demolished, and again resettled some of the population in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. The eastern campaigns failed to secure concrete territorial gains, as there was no serious attempt to retain control of the captured cities, except Camachum (modern Kemah), which was garrisoned. However, under Constantine the Empire had gone on the offensive against the Arabs after over a century of largely defensive warfare. Constantine's major goal in his eastern campaigns seems to have been to forcibly gather up local Christian populations from beyond his borders in order to resettle Thrace. Additionally, the deliberate depopulation of the region beyond the eastern borders created a no-man's land where the concentration and provisioning of Arab armies was made more difficult. This in turn increased the security of Byzantine Anatolia. His military reputation was such that, in 757, the mere rumour of his presence caused an Arab army to retreat. In the same year he agreed a truce and an exchange of prisoners with the Arabs, freeing his army for offensive campaigning in the Balkans.

Events in Italy

With Constantine militarily occupied elsewhere, and the continuance of imperial influence in the West being given a low priority, the Lombard kingAistulf

Aistulf (also Ahistulf, Haistulfus, Astolf etc.; , ; died December 756) was the Duke of Friuli from 744, King of the Lombards from 749, and Duke of Spoleto from 751. His reign was characterized by ruthless and ambitious efforts to conquer Roman ...

captured Ravenna

Ravenna ( ; , also ; ) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire during the 5th century until its Fall of Rome, collapse in 476, after which ...

in 755, ending over two centuries of Byzantine rule in central Italy. The lack of interest Constantine showed in Italian affairs had profound and lasting consequences. Pope Stephen II, seeking protection from the aggression of the Lombards, appealed in person to the Frankish king Pepin the Short

the Short (; ; ; – 24 September 768), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian dynasty, Carolingian to become king.

Pepin was the son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel and his wife Rotrude of H ...

. Pepin cowed Aistulf and restored Stephen to Rome at the head of an army. This began the Frankish involvement in Italy that eventually established Pepin's son Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

as Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

, and also instigated papal temporal rule in Italy with the creation of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

.

Constantine sent a number of unsuccessful embassies to the Lombards, Franks and the papacy to demand the restoration of Ravenna, but never attempted a military reconquest or intervention.

Repeated campaigns against the Bulgarians

The successes in the east made it possible to then pursue an aggressive policy in the Balkans. Constantine aimed to enhance the prosperity and defence of Thrace by the resettlement there of Christian populations transplanted from the east. This influx of settlers, allied to an active re-fortification of the border, caused concern to the Empire's northern neighbour,Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, leading the two states to clash in 755. Kormisosh

Kormisosh (), also known as Kormesiy, Kormesios, Krumesis, Kormisoš, or Cormesius, was a ruler of Bulgaria during the 8th century, recorded in a handful of documents. Modern chronologies of Bulgarian rulers place him either as the successor of Te ...

of Bulgaria raided as far as the Anastasian Wall

The Anastasian Wall (Greek: , ; ) or the Long Walls of Thrace (Greek: , ; Turkish: ''Uzun Duvar'') or simply Long Wall / Macron Teichos () is an ancient stone and turf fortification located west of Istanbul, Turkey, built by the Eastern Roman Em ...

(the outermost defence of the approaches to Constantinople) but was defeated in battle by Constantine, who inaugurated a series of nine successful campaigns against the Bulgarians in the next year, scoring a victory over Kormisosh's successor Vinekh at Marcellae. In 759, Constantine was defeated in the Battle of the Rishki Pass, but the Bulgarians were not able to exploit their success.

Constantine campaigned against the Slav tribes of Thrace and Macedonia in 762, deporting some tribes to the Opsician theme in Anatolia, though some voluntarily requested relocation away from the troubled Bulgarian border region. A contemporary Byzantine source reported that 208,000 Slavs emigrated from Bulgarian controlled areas into Byzantine territory and were settled in Anatolia.

A year later he sailed to Anchialus with 800 ships carrying 9,600 cavalry and some infantry, gaining a victory

The term victory (from ) originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal duel, combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitutes a strategic vi ...

over Khan Telets. Many Bulgar nobles were captured in the battle, and were later slaughtered outside the Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by ...

of Constantinople by the circus factions. Telets was assassinated in the aftermath of his defeat. In 765 the Byzantines again successfully invaded Bulgaria, during this campaign both Constantine's candidate for the Bulgarian throne, Toktu, and his opponent, Pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

, were killed. Pagan was killed by his own slaves when he sought to evade his Bulgarian enemies by fleeing to Varna, where he wished to defect to the Emperor. The cumulative effect of Constantine's repeated offensive campaigns and numerous victories caused considerable instability in Bulgaria, where six monarchs lost their crowns due to their failures in war against Byzantium.

In 775, the Bulgarian ruler Telerig contacted Constantine to ask for sanctuary, saying that he feared that he would have to flee Bulgaria. Telerig enquired as to whom he could trust within Bulgaria, and Constantine foolishly revealed the identities of his agents in the country. The named Byzantine agents were then promptly eliminated. In response, Constantine set out on a new campaign against the Bulgarians, during which he developed carbuncles on his legs. He died during his return journey to Constantinople, on 14 September 775. Though Constantine was unable to destroy the Bulgar state, or impose a lasting peace, he restored imperial prestige in the Balkans.

Assessment and legacy

Constantine V was a highly capable ruler, continuing the reformsfiscal, administrative and militaryof his father. He was also a successful general, not only consolidating the empire's borders, but actively campaigning beyond those borders, both east and west. At the end of his reign the empire had strong finances, a capable army that was proud of its successes and a church that appeared to be subservient to the political establishment.

In concentrating on the security of the empire's core territories he tacitly abandoned some peripheral regions, notably in Italy, which were lost. However, the hostile reaction of the Roman Church and the Italian people to iconoclasm had probably doomed imperial influence in central Italy, regardless of any possible military intervention. Due to his espousal of iconoclasm Constantine was damned in the eyes of contemporary iconodule writers and subsequent generations of Orthodox historians. Typical of this demonisation are the descriptions of Constantine in the writings of Theophanes the Confessor: "a monster athirst for blood", "a ferocious beast", "unclean and bloodstained magician taking pleasure in evoking demons", "a precursor of

Constantine V was a highly capable ruler, continuing the reformsfiscal, administrative and militaryof his father. He was also a successful general, not only consolidating the empire's borders, but actively campaigning beyond those borders, both east and west. At the end of his reign the empire had strong finances, a capable army that was proud of its successes and a church that appeared to be subservient to the political establishment.

In concentrating on the security of the empire's core territories he tacitly abandoned some peripheral regions, notably in Italy, which were lost. However, the hostile reaction of the Roman Church and the Italian people to iconoclasm had probably doomed imperial influence in central Italy, regardless of any possible military intervention. Due to his espousal of iconoclasm Constantine was damned in the eyes of contemporary iconodule writers and subsequent generations of Orthodox historians. Typical of this demonisation are the descriptions of Constantine in the writings of Theophanes the Confessor: "a monster athirst for blood", "a ferocious beast", "unclean and bloodstained magician taking pleasure in evoking demons", "a precursor of Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, Antichrist (or in broader eschatology, Anti-Messiah) refers to a kind of entity prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ and falsely substitute themselves as a savior in Christ's place before ...

". However, to his army and people he was "the victorious and prophetic Emperor". Following a disastrous defeat of the Byzantines by the Bulgarian Khan Krum

Krum (, ), often referred to as Krum the Fearsome () was the Khan of Bulgaria from sometime between 796 and 803 until his death in 814. During his reign the Bulgarian territory doubled in size, spreading from the middle Danube to the Dnieper a ...

in 811 at the Battle of Pliska, troops of the ''tagmata'' broke into Constantine's tomb and implored the dead emperor to lead them once more. The life and actions of Constantine, if freed from the distortion caused by the adulation of his soldiers and the demonisation of iconodule writers, show that he was an effective administrator and gifted general, but he was also autocratic, uncompromising and sometimes needlessly harsh.

All surviving contemporary and later Byzantine histories covering the reign of Constantine were written by iconodules. As a result of this, they are open to suspicion of bias and inaccuracy, particularly when attributing motives to the Emperor, his supporters and opponents. This makes any claims of absolute certainty regarding Constantine's policies and the extent of his repression of iconodules unreliable. In particular, a manuscript written in north-eastern Anatolia concerning miracles attributed to St. Theodore is one of few probably written during or just after the reign of Constantine to survive in its original form; it contains little of the extreme invective common to later iconodule writings. In contrast, the author indicates that iconodules had to make accommodations with imperial iconoclastic policies, and even bestows on Constantine V the conventional religious acclamations: 'Guarded by God' () and 'Christ-loving emperor' ().

Family

By his first wife, Tzitzak ("Irene of Khazaria"), Constantine V had one son:

* Leo IV, who succeeded as emperor. He was crowned in 751.

By his second wife, Maria, Constantine V is not known to have had children.

By his third wife, Eudokia, Constantine V had five sons and a daughter:

* Christopher, ''caesar''

* Nikephoros, ''caesar''

* Niketas, '' nobelissimos''

* Eudokimos, ''nobelissimos''

* Anthimos, ''nobelissimos''

* Anthousa (an iconodule, after her father's death she became a nun, she was later venerated as Saint Anthousa the YoungerConstas, pp. 21–24

By his first wife, Tzitzak ("Irene of Khazaria"), Constantine V had one son:

* Leo IV, who succeeded as emperor. He was crowned in 751.

By his second wife, Maria, Constantine V is not known to have had children.

By his third wife, Eudokia, Constantine V had five sons and a daughter:

* Christopher, ''caesar''

* Nikephoros, ''caesar''

* Niketas, '' nobelissimos''

* Eudokimos, ''nobelissimos''

* Anthimos, ''nobelissimos''

* Anthousa (an iconodule, after her father's death she became a nun, she was later venerated as Saint Anthousa the YoungerConstas, pp. 21–24

See also

*List of Byzantine emperors

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

References

Sources

* Angold, M. (2012) ''Byzantium: The Bridge from Antiquity to the Middle Ages'', Hachette UK, London * Barnard, L. (1977) "The Theology of Images", in ''Iconoclasm'', Bryer, A. and Herrin, J. (eds.), Centre for Byzantine Studies University of Birmingham, pp. 7–13 * Bonner, M. D. (2004) ''Arab-Byzantine Relations in Early Islamic Times'', Ashgate/Variorum, Farnham * Brubaker, L. and Haldon, J. (2011) ''Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era, C. 680–850: A History'', Cambridge University Press, * Bury, J. B. (1923) ''The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: The Eastern Roman Empire'', Cambridge University Press, * Constas, N. (trans.) (1998) "Life of St. Anthousa, Daughter of Constantine V", in ''Byzantine Defenders of Images: Eight Saints' Lives in English Translation'', Talbot, A-M. M. (ed.), Dumbarton Oaks, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA pp. 21–24 * * Dagron, G. (2003) ''Emperor and Priest: The Imperial Office in Byzantium'', Cambridge University Press, * * Finlay, G. (1906) ''History of the Byzantine Empire from 716 to 1057'', J. M. Dent & Sons, London (Reprint 2010 – Kessinger, Whitefish Montana ). First published in 1864 as ''Greece, A History of, From Its Conquest by the Romans to the Present Time: 146 B.C.–1864 A.D.'' (Final revised ed. 7 vols., 1877) * Freely, J. and Cakmak, A. (2004). ''Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul''. Cambridge University Press, * Garland, L. (1999) ''Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium AD 527–1204'', Routledge, London * * Herrin, J. (2007) ''Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire'', Princeton University Press,JSTOR

* Jeffreys, E., Haldon, J.F. and Cormack, R. (eds.) (2008) ''The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies'', Oxford University Press, * Jenkins, R. J. H. (1966) ''Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries, AD 610–1071'', Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London * * Loos, M. (1974) ''Dualist Heresy in the Middle Ages'', Martinus Nijhoff NV, The Hague * * Magdalino, P. (2015) "The People and the Palace", in ''The Emperor's House: Palaces from Augustus to the Age of Absolutism'', Featherstone, M., Spieser, J-M., Tanman, G. and Wulf-Rheidt, U. (eds.), Walter de Gruyter, Göttingen * * Ostrogorsky, G. (1980) ''History of the Byzantine State'', Basil Blackwell, Oxford * Pelikan, J. (1977) ''The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 2: The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600–1700)'', University of Chicago Press, Chicago * Robertson, A. (2017) "The Orient Express: Abbot John's Rapid trip from Constantinople to Ravenna c. AD 700", in ''Byzantine Culture in Translation'', Brown, B. and Neil, B. (eds.), Brill, Leiden * Rochow, I. (1994) ''Kaiser Konstantin V. (741–775). Materialien zu seinem Leben und Nachleben'' (in German), Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, Germany * * Treadgold, W. T. (1995) ''Byzantium and Its Army'', Stanford University Press, Stanford, California * * Treadgold, W. T. (2012) "Opposition to Iconoclasm as Grounds for Civil War", in ''Byzantine War Ideology Between Roman Imperial Concept And Christian Religion'', Koder, J. and Stouratis, I. (eds.), Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, Vienna

JSTOR

* Zuckerman, C. (1988) ''The Reign of Constantine V in the Miracles of St. Theodore the Recruit'', ''Revue des Études Byzantines'', ''tome'' 46, pp. 191–210, ''Institut Français D'Études Byzantines'', Paris,

Literature

* ''The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium

The ''Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium'' (ODB) is a three-volume historical dictionary published by the English Oxford University Press. With more than 5,000 entries, it contains comprehensive information in English on topics relating to the Byzan ...

'', Oxford University Press, 1991.

* Martindale, John et al, (2001). ''Prosopography of the Byzantine Empire

The Prosopography of the Byzantine World (PBW) is a project to create a prosopographical database of individuals named in textual sources in the Byzantine Empire and surrounding areas in the period from 642 to 1265. The project is a collaboration ...

(641-867)''. nline edition http://www.pbe.kcl.ac.uk*

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Constantine 05 8th-century Byzantine emperors Isaurian dynasty Byzantine people of the Arab–Byzantine wars Byzantine people of the Byzantine–Bulgarian Wars 718 births 775 deaths Byzantine Iconoclasm 740s in the Byzantine Empire 750s in the Byzantine Empire 760s in the Byzantine Empire 770s in the Byzantine Empire Leo III the Isaurian Sons of Byzantine emperors Byzantine consuls