Lost-wax casting on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lost-wax castingalso called investment casting, precision casting, or ''cire perdue'' (; borrowed from French)is the process by which a duplicate

Lost-wax castingalso called investment casting, precision casting, or ''cire perdue'' (; borrowed from French)is the process by which a duplicate

File:Lost Wax-Model of apple in wax.jpg, Step 1: A model of an apple in wax

File:Lost Wax-Model of apple in plaster.jpg, Step 2: From the model a rubber mould is made. (The mould is shown here with a solid cast in plaster)

File:Lost Wax-Model of apple in paraffine.jpg, Step 3: From this rubber mould a hollow wax or paraffin cast is made

File:Lost Wax-Moldmaking of an apple.jpg, Step 4: The hollow paraffin apple is covered with a final, fire-proof mould, in this case clay-based, an open view. The core is also filled with fire-proof material. Note the stainless steel core supports. In the next step (not shown), the mould is heated in an oven upside-down and the wax is "lost"

File:Born bronze - Bronze casts.jpg, Step 5: Liquid bronze at 1200°C is poured into the dried and empty casting mould

File:Lost Wax-Apple in bronze.jpg, Step 6: the bronze cast, still with spruing attached. The sprue will be cut away and the final shape polished

The lost-wax casting process may also be used in the production of cast glass sculptures. The original sculpture is made from wax. The sculpture is then covered with mold material (e.g., plaster), except for the bottom of the mold which must remain open. When the mold has hardened, the encased sculpture is removed by applying heat to the bottom of the mold. This melts out the wax (the wax is 'lost') and destroys the original sculpture. The mold is then placed in a kiln upside down with a funnel-like cup on top that holds small chunks of glass. When the kiln is brought up to temperature (1450-1530 degrees Fahrenheit), the glass chunks melt and flow down into the mold. Annealing time is usually 3–5 days, and total kiln time is 5 or more days. After the mold is removed from the kiln, the mold material is removed to reveal the sculpture inside.

The lost-wax casting process may also be used in the production of cast glass sculptures. The original sculpture is made from wax. The sculpture is then covered with mold material (e.g., plaster), except for the bottom of the mold which must remain open. When the mold has hardened, the encased sculpture is removed by applying heat to the bottom of the mold. This melts out the wax (the wax is 'lost') and destroys the original sculpture. The mold is then placed in a kiln upside down with a funnel-like cup on top that holds small chunks of glass. When the kiln is brought up to temperature (1450-1530 degrees Fahrenheit), the glass chunks melt and flow down into the mold. Annealing time is usually 3–5 days, and total kiln time is 5 or more days. After the mold is removed from the kiln, the mold material is removed to reveal the sculpture inside.

Cast gold knucklebones, beads, and bracelets, found in graves at Bulgaria's

Cast gold knucklebones, beads, and bracelets, found in graves at Bulgaria's

Some of the oldest known examples of the lost-wax technique are the objects discovered in the Nahal Mishmar hoard in southern

Some of the oldest known examples of the lost-wax technique are the objects discovered in the Nahal Mishmar hoard in southern

The oldest known example of applying the lost-wax technique to copper casting comes from a 6,000-year-old () copper, wheel-shaped

The oldest known example of applying the lost-wax technique to copper casting comes from a 6,000-year-old () copper, wheel-shaped  Gupta and post-Gupta period bronze figures have been recovered from the following sites: Saranath, Mirpur-Khas (in

Gupta and post-Gupta period bronze figures have been recovered from the following sites: Saranath, Mirpur-Khas (in

world

The technique was used throughout India, as well as in the neighbouring countries

The inhabitants of Ban Na Di were casting bronze from to 200 AD, using the lost-wax technique to manufacture bangles. Bangles made by the lost-wax process are characteristic of northeast

The inhabitants of Ban Na Di were casting bronze from to 200 AD, using the lost-wax technique to manufacture bangles. Bangles made by the lost-wax process are characteristic of northeast

Direct imitations and local derivations of Oriental, Syro- Palestinian and Cypriot

Direct imitations and local derivations of Oriental, Syro- Palestinian and Cypriot  Examples of works made using the lost-wax casting process in

Examples of works made using the lost-wax casting process in

There is great variability in the use of the lost-wax method in East Asia. The casting method to make bronzes till the early phase of Eastern Zhou (770-256 ) was almost invariably section-mold process. Starting from around 600 , there was an unmistakable rise of lost-wax casting in the central plains of China, first witnessed in the Chu cultural sphere.

Further investigations have revealed this not to be the case as it is clear that the piece-mould casting method was the principal technique used to manufacture bronze vessels in

There is great variability in the use of the lost-wax method in East Asia. The casting method to make bronzes till the early phase of Eastern Zhou (770-256 ) was almost invariably section-mold process. Starting from around 600 , there was an unmistakable rise of lost-wax casting in the central plains of China, first witnessed in the Chu cultural sphere.

Further investigations have revealed this not to be the case as it is clear that the piece-mould casting method was the principal technique used to manufacture bronze vessels in

Some early literary works allude to lost-wax casting. Columella, a Roman writer of the 1st century AD, mentions the processing of wax from beehives in ''De Re Rustica'', perhaps for casting, as does

Some early literary works allude to lost-wax casting. Columella, a Roman writer of the 1st century AD, mentions the processing of wax from beehives in ''De Re Rustica'', perhaps for casting, as does

File:Fusione di un bronzo a cera persa, fase 3.JPG, A wax model is sprued with vents for casting metal and for the release of air, and covered in heat-resistant material.

File:Fusione di un bronzo a cera persa, fase 4.JPG, A cast in bronze, still with spruing

File:Fusione di un bronzo a cera persa, fase 5.JPG, A bronze cast, with part of the spruing cut away

File:Fusione di un bronzo a cera persa, fase 6.JPG, A nearly finished bronze casting. Only the core supports have yet to be removed and closed

File:HugoRheinholdApeWithSkull.DarwinMonkey.1.jpg, Hugo Rheinhold's '' Affe mit Schädel'' is cast out of bronze using the lost-wax process.

File:Lazy Lady, Rowan Gillespie.jpg, This bronze piece entitled ''Lazy Lady'', by the sculptor Rowan Gillespie was cast using the lost-wax process.

File:Sculpture_Staendehausbrunnen_Emil_Cimiotti_Karmarschstrasse_Hanover_Germany_01.jpg, The ''Blätterbrunnen'' of 1976 by Emil Cimiotti, as seen 2014 in the city center of Hanover, Germany. A lost-wax method was used for the bronze leaves.

Lost-wax castingalso called investment casting, precision casting, or ''cire perdue'' (; borrowed from French)is the process by which a duplicate

Lost-wax castingalso called investment casting, precision casting, or ''cire perdue'' (; borrowed from French)is the process by which a duplicate sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

(often a metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

, such as silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

, or bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

) is cast from an original sculpture. Intricate works can be achieved by this method.

The oldest known examples of this technique are approximately 6,500 years old (4550–4450 BC) and attributed to gold artefacts found at Bulgaria's Varna Necropolis

The Varna Necropolis (), or Varna Cemetery, is a burial site in the western industrial zone of Varna, Bulgaria, Varna (approximately half a kilometre from Lake Varna and 4 km from the city centre), internationally considered one of the key a ...

. A copper amulet from Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh is a Neolithic archaeological site situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan, Pakistan, Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, ...

, Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE ...

, in present-day Pakistan, is dated to circa 4,000 BC. Cast copper objects, found in the Nahal Mishmar hoard in southern Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, which belong to the Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in di ...

period (4500–3500 BC), are estimated, from carbon-14 dating, to date to circa 3500 BC. Other examples from somewhat later periods are from Mesopotamia in the third millennium BC. Lost-wax casting was widespread in Europe until the 18th century, when a piece-moulding process came to predominate.

The steps used in casting small bronze sculptures are fairly standardized, though the process today varies from foundry to foundry (in modern industrial use, the process is called investment casting). Variations of the process include: "lost mould", which recognizes that materials other than wax can be used (such as tallow, resin

A resin is a solid or highly viscous liquid that can be converted into a polymer. Resins may be biological or synthetic in origin, but are typically harvested from plants. Resins are mixtures of organic compounds, predominantly terpenes. Commo ...

, tar, and textile

Textile is an Hyponymy and hypernymy, umbrella term that includes various Fiber, fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, Staple (textiles)#Filament fiber, filaments, Thread (yarn), threads, and different types of #Fabric, fabric. ...

); and "waste wax process" (or "waste mould casting"), because the mould is destroyed to remove the cast item.

Process

Casts can be made of the wax model itself, the direct method, or of a wax copy of a model that need not be of wax, the indirect method. These are the steps for the indirect process (the direct method starts at step 7): #Model-making. An artist or mould-maker creates an original model from wax,clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

, or another material. Wax and oil-based clay are often preferred because these materials retain their softness.

#Mouldmaking. A mould is made of the original model or sculpture. The rigid outer moulds contain the softer inner mould, which is the exact negative of the original model. Inner moulds are usually made of latex

Latex is an emulsion (stable dispersion) of polymer microparticles in water. Latices are found in nature, but synthetic latices are common as well.

In nature, latex is found as a wikt:milky, milky fluid, which is present in 10% of all floweri ...

, polyurethane rubber or silicone

In Organosilicon chemistry, organosilicon and polymer chemistry, a silicone or polysiloxane is a polymer composed of repeating units of siloxane (, where R = Organyl group, organic group). They are typically colorless oils or elastomer, rubber ...

, which is supported by the outer mould. The outer mould can be made from plaster, but can also be made of fiberglass

Fiberglass (American English) or fibreglass (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English) is a common type of fibre-reinforced plastic, fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened i ...

or other materials. Most moulds are made of at least two pieces, and a shim with keys is placed between the parts during construction so that the mould can be put back together accurately. If there are long, thin pieces extending out of the model, they are often cut off of the original and moulded separately. Sometimes many moulds are needed to recreate the original model, especially for large models.

#Wax. Once the mould is finished, molten wax is poured into it and swished around until an even coating, usually about 3 mm ( inch) thick, covers the inner surface of the mould. This is repeated until the desired thickness is reached. Another method is to fill the entire mould with molten wax and let it cool until a desired thickness has set on the surface of the mould. After this the rest of the wax is poured out again, the mould is turned upside down and the wax layer is left to cool and harden. With this method it is more difficult to control the overall thickness of the wax layer.

#Removal of wax. This hollow wax copy of the original model is removed from the mould. The model-maker may reuse the mould to make multiple copies, limited only by the durability of the mould.

#Chasing. Each hollow wax copy is then "chased": a heated metal tool is used to rub out the marks that show the parting line or flashing where the pieces of the mould came together. The wax is dressed to hide any imperfections. The wax now looks like the finished piece. Wax pieces that were moulded separately can now be heated and attached; foundries often use registration marks to indicate exactly where they go.

#Spruing. The wax copy is sprued with a treelike structure of wax that will eventually provide paths for the molten casting material to flow and for air to escape. The carefully planned spruing usually begins at the top with a wax "cup," which is attached by wax cylinders to various points on the wax copy. The spruing does not have to be hollow, as it will be melted out later in the process.

#Slurry. A sprued wax copy is dipped into a slurry of silica, then into a sand-like stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and ...

, or dry crystalline silica of a controlled grain size. The slurry and grit combination is called ceramic shell mould material, although it is not literally made of ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcela ...

. This shell is allowed to dry, and the process is repeated until at least a half-inch coating covers the entire piece. The bigger the piece, the thicker the shell needs to be. Only the inside of the cup is not coated, and the cup's flat top serves as the base upon which the piece stands during this process. The core is also filled with fire-proof material.

#Burnout. The ceramic shell-coated piece is placed cup-down in a kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or Chemical Changes, chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects m ...

, whose heat hardens the silica coatings into a shell, and the wax melts and runs out. The melted wax can be recovered and reused, although it is often simply burned up. Now all that remains of the original artwork is the negative space formerly occupied by the wax, inside the hardened ceramic shell. The feeder, vent tubes and cup are also now hollow.

#Testing. The ceramic shell is allowed to cool, then is tested to see if water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

will flow freely through the feeder and vent tubes. Cracks or leaks can be patched with thick refractory paste. To test the thickness, holes can be drilled into the shell, then patched.

#Pouring. The shell is reheated in the kiln to harden the patches and remove all traces of moisture, then placed cup-upward into a tub filled with sand. Metal is melted in a crucible in a furnace, then poured carefully into the shell. The shell has to be hot because otherwise the temperature difference would shatter it. The filled shells are then allowed to cool.

#Release. The shell is hammered or sand-blasted away, releasing the rough casting. The sprues, which are also faithfully recreated in metal, are cut off, the material to be reused in another casting.

#Metal-chasing. Just as the wax copies were chased, the casting is worked until the telltale signs of the casting process are removed, so that the casting now looks like the original model. Pits left by air bubbles in the casting and the stubs of the spruing are filed down and polished.

Prior to silica-based casting moulds, these moulds were made of a variety of other fire-proof materials, the most common being plaster based, with added grout, and clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

based. Prior to rubber moulds gelatine was used.

Jewellery and small parts

The methods used for small parts andjewellery

Jewellery (or jewelry in American English) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment such as brooches, ring (jewellery), rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the ...

vary somewhat from those used for sculpture. A wax model is obtained either from injection into a rubber mould or by being custom-made by carving. The wax or waxes are sprued and fused onto a rubber base, called a "sprue base". Then a metal flask, which resembles a short length of steel pipe that ranges roughly from 3.5 to 15 centimeters tall and wide, is put over the sprue base and the waxes. Most sprue bases have a circular rim which grips the standard-sized flask, holding it in place. Investment (refractory plaster) is mixed and poured into the flask, filling it. It hardens, then is burned out as outlined above. Casting is usually done straight from the kiln either by centrifugal casting or vacuum casting.

The lost-wax process can be used with any material that can burn, melt, or evaporate to leave a mould cavity. Some automobile

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, peopl ...

manufacturers use a lost-foam technique to make engine blocks. The model is made of polystyrene

Polystyrene (PS) is a synthetic polymer made from monomers of the aromatic hydrocarbon styrene. Polystyrene can be solid or foamed. General-purpose polystyrene is clear, hard, and brittle. It is an inexpensive resin per unit weight. It i ...

foam, which is placed into a casting flask, consisting of a cope and drag, which is then filled with casting sand. The foam supports the sand, allowing shapes that would be impossible if the process had to rely on the sand alone. The metal is poured in, vaporizing the foam with its heat.

In dentistry, gold crowns, inlays and onlays are made by the lost-wax technique. Application of Lost Wax technique for the fabrication of cast inlay was first reported by Taggart. A typical gold alloy is about 60% gold and 28% silver with copper and other metals making up the rest. Careful attention to tooth preparation, impression taking and laboratory technique are required to make this type of restoration a success. Dental laboratories make other items this way as well.

Textiles

In this process, the wax and the textile are both replaced by the metal during the casting process, whereby the fabric reinforcement allows for a thinner model, and thus reduces the amount of metal expended in the mould. Evidence of this process is seen by the textile relief on the reverse side of objects and is sometimes referred to as "lost-wax, lost textile". This textile relief is visible ongold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

ornaments from burial mounds in southern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

of the ancient horse riding tribes, such as the distinctive group of openwork gold plaques housed in the Hermitage Museum

The State Hermitage Museum ( rus, Государственный Эрмитаж, r=Gosudarstvennyj Ermitaž, p=ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj ɪrmʲɪˈtaʂ, links=no) is a museum of art and culture in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and holds the large ...

, Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

. The technique may have its origins in the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

, as indicated by the few Han examples, and the bronze buckle and gold plaques found at the cemetery

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite, graveyard, or a green space called a memorial park or memorial garden, is a place where the remains of many death, dead people are burial, buried or otherwise entombed. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek ...

at Xigou. Such a technique may also have been used to manufacture some Viking Age

The Viking Age (about ) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. The Viking Age applies not only to their ...

oval brooches, indicated by numerous examples with fabric imprints such as those of Castletown (Scotland).

Glass sculptures

The lost-wax casting process may also be used in the production of cast glass sculptures. The original sculpture is made from wax. The sculpture is then covered with mold material (e.g., plaster), except for the bottom of the mold which must remain open. When the mold has hardened, the encased sculpture is removed by applying heat to the bottom of the mold. This melts out the wax (the wax is 'lost') and destroys the original sculpture. The mold is then placed in a kiln upside down with a funnel-like cup on top that holds small chunks of glass. When the kiln is brought up to temperature (1450-1530 degrees Fahrenheit), the glass chunks melt and flow down into the mold. Annealing time is usually 3–5 days, and total kiln time is 5 or more days. After the mold is removed from the kiln, the mold material is removed to reveal the sculpture inside.

The lost-wax casting process may also be used in the production of cast glass sculptures. The original sculpture is made from wax. The sculpture is then covered with mold material (e.g., plaster), except for the bottom of the mold which must remain open. When the mold has hardened, the encased sculpture is removed by applying heat to the bottom of the mold. This melts out the wax (the wax is 'lost') and destroys the original sculpture. The mold is then placed in a kiln upside down with a funnel-like cup on top that holds small chunks of glass. When the kiln is brought up to temperature (1450-1530 degrees Fahrenheit), the glass chunks melt and flow down into the mold. Annealing time is usually 3–5 days, and total kiln time is 5 or more days. After the mold is removed from the kiln, the mold material is removed to reveal the sculpture inside.

Archaeological history

Black Sea

Cast gold knucklebones, beads, and bracelets, found in graves at Bulgaria's

Cast gold knucklebones, beads, and bracelets, found in graves at Bulgaria's Varna Necropolis

The Varna Necropolis (), or Varna Cemetery, is a burial site in the western industrial zone of Varna, Bulgaria, Varna (approximately half a kilometre from Lake Varna and 4 km from the city centre), internationally considered one of the key a ...

, have been dated to approximately 6500 years BP. They are believed to be both some of the oldest known manufactured golden objects, and the oldest objects known to have been made using lost wax casting.

Middle East

Some of the oldest known examples of the lost-wax technique are the objects discovered in the Nahal Mishmar hoard in southern

Some of the oldest known examples of the lost-wax technique are the objects discovered in the Nahal Mishmar hoard in southern Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definition ...

, and which belong to the Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in di ...

period (4500–3500 BC). Conservative Carbon-14 estimates date the items to around 3700 BC, making them more than 5700 years old.

Near East

InMesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, from –2750 BC, the lost-wax technique was used for small-scale, and then later large-scale copper and bronze statues. One of the earliest surviving lost-wax castings is a small lion pendant from Uruk IV. Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

ian metalworkers were practicing lost-wax casting from approximately –3200 BC. Much later examples from northeastern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

/Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

include the Great Tumulus at Gordion (late 8th century BC), as well as other types of Urartian cauldron attachments.

South Asia

The oldest known example of applying the lost-wax technique to copper casting comes from a 6,000-year-old () copper, wheel-shaped

The oldest known example of applying the lost-wax technique to copper casting comes from a 6,000-year-old () copper, wheel-shaped amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word , which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protects a perso ...

found at Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh is a Neolithic archaeological site situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan, Pakistan, Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, ...

, Pakistan.

Metal casting, by the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE ...

, produced some of the earliest known examples of lost-wax casting applied to the casting of copper alloys, a bronze figurine, found at Mohenjo-daro, and named the " dancing girl", is dated to 2300-1750 . Other examples include the buffalo, bull and dog found at Mohenjodaro and Harappa, two copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

figures found at the Harappan site Lothal in the district of Ahmedabad of Gujarat, and likely a covered cart with wheels missing and a complete cart with a driver found at Chanhudaro.

During the post-Harappan period, hoards of copper and bronze implements made by the lost-wax process are known from Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

, Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh ( ; UP) is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. With over 241 million inhabitants, it is the List of states and union territories of India by population, most populated state in In ...

, Bihar

Bihar ( ) is a states and union territories of India, state in Eastern India. It is the list of states and union territories of India by population, second largest state by population, the List of states and union territories of India by are ...

, Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (; ; ) is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal and the largest city is Indore, Indore. Other major cities includes Gwalior, Jabalpur, and Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, Sagar. Madhya Pradesh is the List of states and union te ...

, Odisha

Odisha (), formerly Orissa (List of renamed places in India, the official name until 2011), is a States and union territories of India, state located in East India, Eastern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by ar ...

, Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (ISO 15919, ISO: , , AP) is a States and union territories of India, state on the East Coast of India, east coast of southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, seventh-largest state and th ...

and West Bengal

West Bengal (; Bengali language, Bengali: , , abbr. WB) is a States and union territories of India, state in the East India, eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabi ...

. Gold and copper ornaments, apparently Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

in style, made by ''cire perdue'' were found at the ruins at Sirkap. One example of this Indo-Greek art dates to the the juvenile figure of Harpocrates

Harpocrates (, Phoenician language, Phoenician: 𐤇𐤓𐤐𐤊𐤓𐤈, romanized: ḥrpkrṭ, ''harpokratēs'') is the god of silence, secrets and confidentiality in the Hellenistic religion developed in History of Alexandria#Ptolemaic era ...

excavated at Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila () is a city in the Pothohar region of Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area and is just south of the ...

. Bronze icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic Church, Catholic, and Lutheranism, Lutheran churches. The most common subjects include Jesus, Mary, mother of ...

s were produced during the 3rd and 4th centuries, such as the Buddha image at Amaravati

Amaravati ( , Telugu language, Telugu: ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It is located in Guntur district on the right bank of the Krishna River, southwest of Vijayawada. The city derives its name from the nearby his ...

, and the images of Rama

Rama (; , , ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the seventh and one of the most popular avatars of Vishnu. In Rama-centric Hindu traditions, he is considered the Supreme Being. Also considered as the ideal man (''maryāda' ...

and Kartikeya

Kartikeya (/Sanskrit phonology, kɑɾt̪ɪkejə/; ), also known as Skanda (Sanskrit phonology, /skən̪d̪ə/), Subrahmanya (/Sanskrit phonology, sʊbɾəɦməɲjə/, /ɕʊ-/), Shanmukha (Sanskrit phonology, /ɕɑnmʊkʰə/) and Murugan ...

in the Guntur

Guntur (), natively spelt as Gunturu, is a city in the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Andhra Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of Guntur district. The city is part of the Andhra Pradesh Capital Region and is lo ...

district of Andhra Pradesh. A further two bronze images of Parsvanatha and a small hollow-cast bull came from Sahribahlol, Gandhara

Gandhara () was an ancient Indo-Aryan people, Indo-Aryan civilization in present-day northwest Pakistan and northeast Afghanistan. The core of the region of Gandhara was the Peshawar valley, Peshawar (Pushkalawati) and Swat valleys extending ...

, and a standing Tirthankara

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (; ) is a saviour and supreme preacher of the ''Dharma (Jainism), dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the founder of a ''Tirtha (Jainism), tirtha'', a fordable passage across ''Saṃsā ...

() from Chausa in Bihar should be mentioned here as well. Other notable bronze figures and images have been found in Rupar, Mathura (in Uttar Pradesh) and Brahmapura, Maharashtra

Maharashtra () is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to th ...

.

Gupta and post-Gupta period bronze figures have been recovered from the following sites: Saranath, Mirpur-Khas (in

Gupta and post-Gupta period bronze figures have been recovered from the following sites: Saranath, Mirpur-Khas (in Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

), Sirpur (District of Raipur), Balaighat (near Mahasthan now in Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

), Akota (near Vadodara, Gujarat), Vasantagadh, Chhatarhi, Barmer and Chambi (in Rajesthan). The bronze casting technique and making of bronze images of traditional icons reached a high stage of development in South India during the medieval period. Although bronze images were modelled and cast during the Pallava Period in the eighth and ninth centuries, some of the most beautiful and exquisite statues were produced during the Chola Period in Tamil Nadu from the tenth to the twelfth century. The technique and art of fashioning bronze images is still skillfully practised in South India, particularly in Kumbakonam. The distinguished patron during the tenth century was the widowed Chola queen, Sembiyan Maha Devi. Chola bronzes are the most soughtafter collectors’ items by art lovers all over thworld

The technique was used throughout India, as well as in the neighbouring countries

Nepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

, Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

and Siam.

Southeast Asia

The inhabitants of Ban Na Di were casting bronze from to 200 AD, using the lost-wax technique to manufacture bangles. Bangles made by the lost-wax process are characteristic of northeast

The inhabitants of Ban Na Di were casting bronze from to 200 AD, using the lost-wax technique to manufacture bangles. Bangles made by the lost-wax process are characteristic of northeast Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

. Some of the bangles from Ban Na Di revealed a dark grey substance between the central clay core and the metal, which on analysis was identified as an unrefined form of insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

wax. It is likely that decorative items, like bracelet

A bracelet is an article of jewellery that is worn around the wrist. Bracelets may serve different uses, such as being worn as an ornament. When worn as ornaments, bracelets may have a supportive function to hold other items of decoration, ...

s and rings, were made by ''cire perdue'' at Non Nok Tha and Ban Chiang. There are technological and material parallels between northeast Thailand and Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

concerning the lost-wax technique. The sites exhibiting artifacts made by the lost-mould process in Vietnam, such as the Dong Son drums, come from the Dong Son, and Phung Nguyen cultures, such as one sickle and the figure of a seated individual from Go Mun (near Phung Nguyen, the Bac Bo Region), dating to the Go Mun phase (end of the General B period, up until the 7th century BC).

West Africa

Cast bronzes are known to have been produced inAfrica

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

by the 9th century AD in Igboland ( Igbo-Ukwu) in Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

, the 12th century AD in Yorubaland

Yorubaland () is the homeland and cultural region of the Yoruba people in West Africa. It spans the modern-day countries of Nigeria, Togo and Benin, and covers a total land area of . Of this land area, 106,016 km2 (74.6%) lies within Niger ...

( Ife) and the 15th century AD in the kingdom of Benin

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as Great Benin, is a traditional kingdom in southern Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th century until 1975. The Kingdom of Benin's c ...

. Some portrait heads remain.

Benin

Benin, officially the Republic of Benin, is a country in West Africa. It was formerly known as Dahomey. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north-west, and Niger to the north-east. The majority of its po ...

mastered bronze during the 16th century, produced portraiture and reliefs in the metal using the lost wax process.

Egypt

TheEgyptians

Egyptians (, ; , ; ) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian identity is closely tied to Geography of Egypt, geography. The population is concentrated in the Nile Valley, a small strip of cultivable land stretchi ...

were practicing ''cire perdue'' from the mid 3rd millennium BC, shown by Early Dynastic bracelets and gold jewellery. Inserted spouts for ewers (copper water vessels) from the Fourth Dynasty (Old Kingdom) were made by the lost-wax method.Ogden, J. (2000). Metals, in ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology'', eds. P. T. Nicholson & I. Shaw Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hollow castings, such as the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

statuette from the Fayum find appeared during the Middle Kingdom, followed by solid cast statuettes (like the squatting, nursing mother

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of ges ...

, in Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

) of the Second Intermediate/Early New Kingdom. The hollow casting of statues is represented in the New Kingdom by the kneeling

Kneeling is a basic human position where one or both knees touch the ground. According to Merriam-Webster, kneeling is defined as "to position the body so that one or both knees rest on the floor". Kneeling with only one knee, and not both, is ca ...

statue of Tuthmosis IV (British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

) and the head fragment of Ramesses V (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). Hollow castings become more detailed and continue into the Eighteenth Dynasty, shown by the black bronze kneeling figure of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

( Museum of the University of Pennsylvania). ''Cire Perdue'' is used in mass-production during the Late Period to Graeco- Roman times when figures of deities

A deity or god is a supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to having authority over some aspect of the universe and/or life. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines ''deity'' as a God (male deity), god or god ...

were cast for personal devotion and votive temple offerings. Nude female-shaped handles on bronze mirror

A mirror, also known as a looking glass, is an object that Reflection (physics), reflects an image. Light that bounces off a mirror forms an image of whatever is in front of it, which is then focused through the lens of the eye or a camera ...

s were cast by the lost-wax process.

Mediterranean

The lost-wax technique came to be known in theMediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

during the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

. It was a major metalworking technique utilized in the ancient Mediterranean world, notably during the Classical period of Greece for large-scale bronze statuary and in the Roman world.

figurine

A figurine (a diminutive form of the word ''figure'') or statuette is a small, three-dimensional sculpture that represents a human, deity or animal, or, in practice, a pair or small group of them. Figurines have been made in many media, with cla ...

s are found in Late Bronze Age Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

, with a local production of figurines from the 11th to 10th century BC. The cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a corpse through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and ...

graves (mainly 8th-7th centuries BC, but continuing until the beginning of the 4th century) from the necropolis of Paularo (Italian Oriental Alps) contained fibulae, pendants and other copper-based objects that were made by the lost-wax process. Etruscan examples, such as the bronze anthropomorphic handle from the Bocchi collection (National Archaeological Museum of Adria

Adria is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Rovigo in the Veneto region of northern Italy, situated between the mouths of the rivers Adige and Po River, Po. The remains of the Etruria, Etruscan city of Atria or Hatria are to be found below ...

), dating back to the 6th to 5th centuries BC, were made by ''cire perdue''. Most of the handles in the Bocchi collection, as well as some bronze vessels found in Adria (Rovigo

Rovigo (, ; ) is a city and communes of Italy, commune in the region of Veneto, Northeast Italy, the capital of the province of Rovigo, eponymous province.

Geography

Rovigo stands on the low ground known as Polesine, by rail southwest of Veni ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

) were made using the lost-wax technique. The better known lost-wax produced items from the classical world include the "Praying Boy" (in the Berlin Museum), the statue of Hera

In ancient Greek religion, Hera (; ; in Ionic Greek, Ionic and Homeric Greek) is the goddess of marriage, women, and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she is queen of the twelve Olympians and Mount Oly ...

from Vulci (Etruria), which, like most statues, was cast in several parts which were then joined.Neuburger, A., 1930. ''The Technical Arts and Sciences of the Ancients'', London: Methuen & Co. Ltd. Geometric bronzes such as the four copper horses of San Marco (Venice, probably 2nd century) are other prime examples of statues cast in many parts.

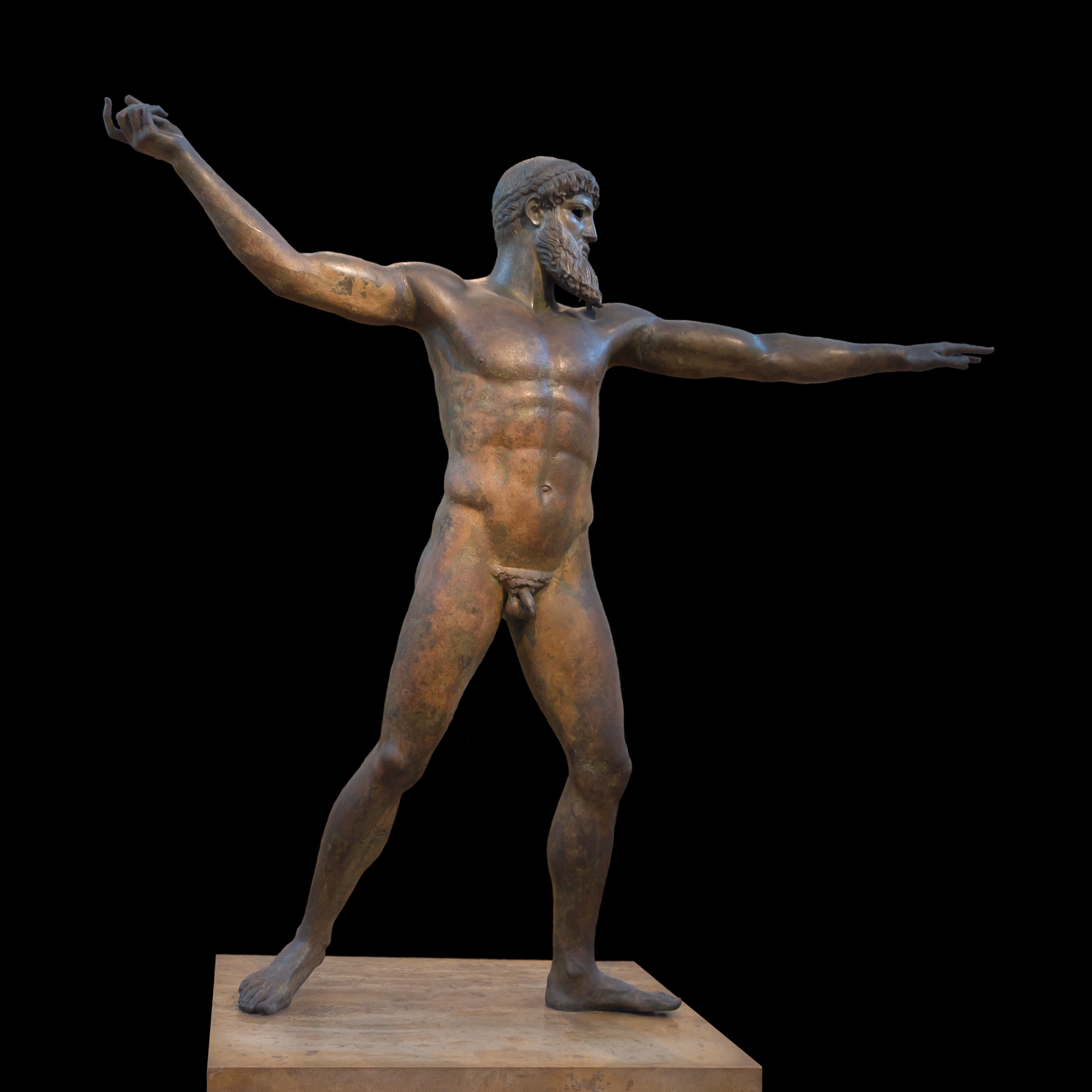

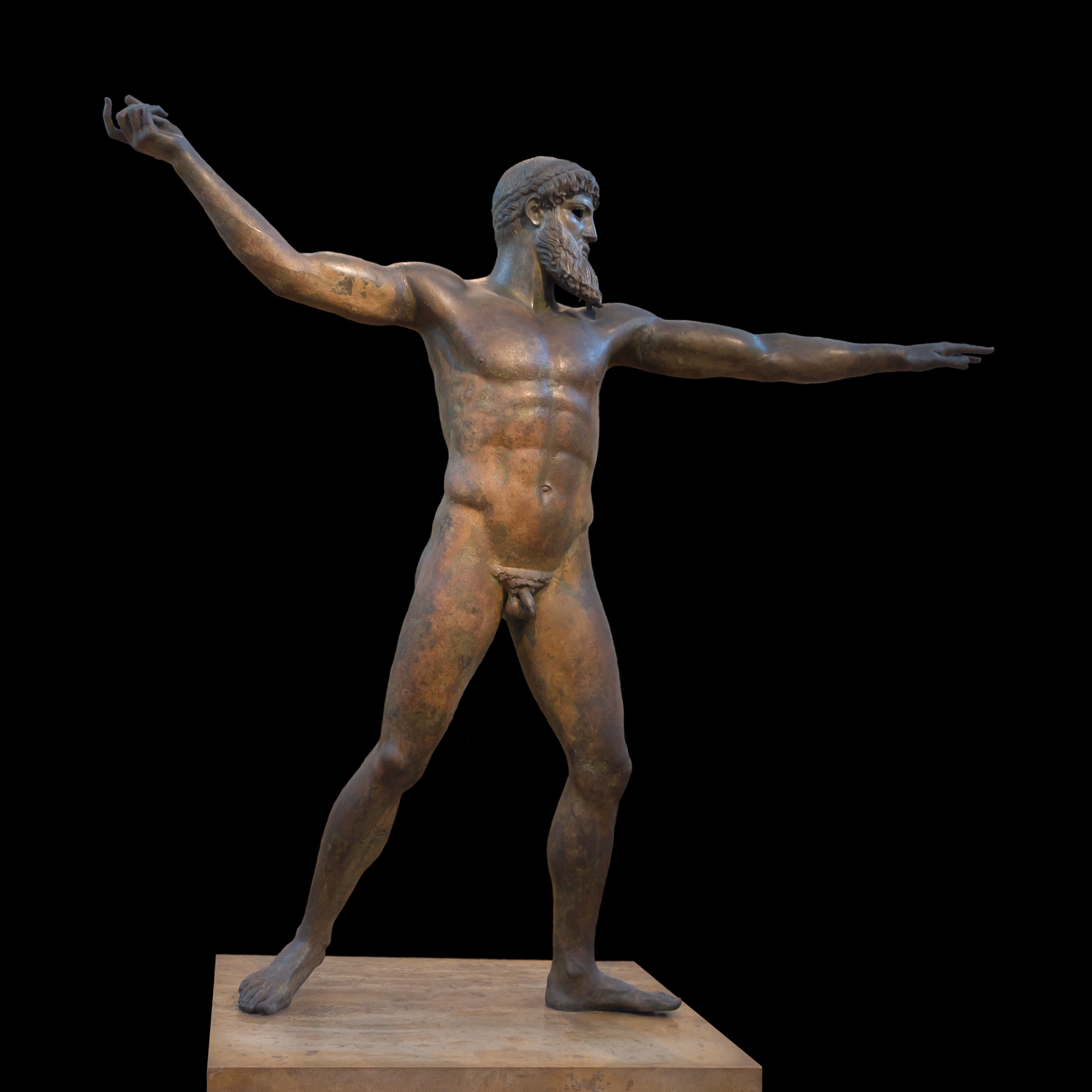

Examples of works made using the lost-wax casting process in

Examples of works made using the lost-wax casting process in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

largely are unavailable due to the common practice in later periods of melting down pieces to reuse their materials. Much of the evidence for these products come from shipwreck

A shipwreck is the wreckage of a ship that is located either beached on land or sunken to the bottom of a body of water. It results from the event of ''shipwrecking'', which may be intentional or unintentional. There were approximately thre ...

s. As underwater archaeology became feasible, artifacts lost to the sea became more accessible. Statues like the Artemision Bronze Zeus or Poseidon (found near Cape Artemision), as well as the Victorious Youth (found near Fano

Fano () is a city and ''comune'' of the province of Pesaro and Urbino in the Marche region of Italy. It is a beach resort southeast of Pesaro, located where the ''Via Flaminia'' reaches the Adriatic Sea. It is the third city in the region by pop ...

), are two such examples of Greek lost-wax bronze statuary that were discovered underwater.

Some Late Bronze Age sites in Cyprus have produced cast bronze figures of humans and animals. One example is the male figure found at Enkomi. Three objects from Cyprus (held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

in New York) were cast by the lost-wax technique from the 13th and 12th centuries BC, namely, the amphora

An amphora (; ; English ) is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storage rooms and packages, tied together with rope and delivered by land ...

e rim, the rod tripod

A tripod is a portable three-legged frame or stand, used as a platform for supporting the weight and maintaining the stability of some other object. The three-legged (triangular stance) design provides good stability against gravitational loads ...

, and the cast tripod.

Other, earlier examples that show this assembly of lost-wax cast pieces include the bronze head of the Chatsworth Apollo and the bronze head of Aphrodite

Aphrodite (, ) is an Greek mythology, ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, procreation, and as her syncretism, syncretised Roman counterpart , desire, Sexual intercourse, sex, fertility, prosperity, and ...

from Satala (Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

) from the British Museum.; See also

East Asia

There is great variability in the use of the lost-wax method in East Asia. The casting method to make bronzes till the early phase of Eastern Zhou (770-256 ) was almost invariably section-mold process. Starting from around 600 , there was an unmistakable rise of lost-wax casting in the central plains of China, first witnessed in the Chu cultural sphere.

Further investigations have revealed this not to be the case as it is clear that the piece-mould casting method was the principal technique used to manufacture bronze vessels in

There is great variability in the use of the lost-wax method in East Asia. The casting method to make bronzes till the early phase of Eastern Zhou (770-256 ) was almost invariably section-mold process. Starting from around 600 , there was an unmistakable rise of lost-wax casting in the central plains of China, first witnessed in the Chu cultural sphere.

Further investigations have revealed this not to be the case as it is clear that the piece-mould casting method was the principal technique used to manufacture bronze vessels in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. The lost-wax technique did not appear in northern China until the 6th century BC. Lost-wax casting is known as ''rōgata'' in Japanese, and dates back to the Yayoi period

The Yayoi period (弥生時代, ''Yayoi jidai'') (c. 300 BC – 300 AD) is one of the major historical periods of the Japanese archipelago. It is generally defined as the era between the beginning of food production in Japan and the emergence o ...

, . The most famous piece made by ''cire perdue'' is the bronze image of Buddha in the temple of the Todaiji monastery at Nara

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an independent agency of the United States government within the executive branch, charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It is also task ...

. It was made in sections between 743 and 749, allegedly using seven tons of wax.

Northern Europe

The Dunaverney (1050–910 BC) and Little Thetford (1000–701 BC) flesh-hooks have been shown to be made using a lost-wax process. The Little Thetford flesh-hook, in particular, employed distinctly inventive construction methods. The intricate Gloucester Candlestick (1104–1113 AD) was made as a single-piece wax model, then given a complex system of gates and vents before being invested in a mould.Americas

The lost-wax casting tradition was developed by the peoples ofNicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

, Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

, Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

, northwest Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

, Andean America, and the western portion of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

. Lost-wax casting produced some of the region's typical gold wire

file:Sample cross-section of high tension power (pylon) line.jpg, Overhead power cabling. The conductor consists of seven strands of steel (centre, high tensile strength), surrounded by four outer layers of aluminium (high conductivity). Sample d ...

and delicate wire ornament, such as fine ear ornaments. The process was employed in prehispanic times in Colombia's Muisca and Sinú cultural areas. Two lost-wax moulds, one complete and one partially broken, were found in a shaft and chamber tomb in the vereda of Pueblo Tapado in the municipio of Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

( Department of Quindío), dated roughly to the pre-Columbian period. The lost-wax method did not appear in Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

until the 10th century,Hodges, H., 1970. ''Technology in the Ancient World'', London: Allen Lane The Penguin Press. and was thereafter used in western Mexico to make a wide range of bell forms.

Literary history

Indirect evidence

Some early literary works allude to lost-wax casting. Columella, a Roman writer of the 1st century AD, mentions the processing of wax from beehives in ''De Re Rustica'', perhaps for casting, as does

Some early literary works allude to lost-wax casting. Columella, a Roman writer of the 1st century AD, mentions the processing of wax from beehives in ''De Re Rustica'', perhaps for casting, as does Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

, who details a sophisticated procedure for making Punic wax. One Greek inscription

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

refers to the payment of craftsmen for their work on the Erechtheum in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

(408/7–407/6 BC). Clay-modellers may use clay moulds to make terracotta negatives for casting or to produce wax positives. Pliny portrays as a well-reputed ancient artist producing bronze statues, Jex-Blake, K. & E. Sellers, 1967. ''The Elder Pliny's Chapters on The History of Art''., Chicago: Ares Publishers, Inc. and describes Lysistratos of Sikyon, who takes plaster casts from living faces to create wax casts using the indirect process.

Many bronze statues or parts of statues in antiquity were cast using the lost wax process. Theodorus of Samos is commonly associated with bronze casting.Pausania, Description of Greece 8.14.8 Pliny also mentions the use of lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

, which is known to help molten bronze flow into all areas and parts of complex moulds. Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quin ...

documents the casting of statues in parts, whose moulds may have been produced by the lost wax process. Scenes on the early-5th century BC Berlin Foundry Cup depict the creation of bronze statuary working, probably by the indirect method of lost-wax casting.

Direct evidence

India

The lost-wax method is well documented in ancient Indian literary sources. The '' Shilpa Shastras'', a text from the Gupta Period (–550 AD), contains detailed information about casting images in metal. The 5th-century AD '' Vishnusamhita'', an appendix to the '' Vishnu Purana'', refers directly to the modeling of wax for making metal objects in chapter XIV: "if an image is to be made of metal, it must first be made of wax." Chapter 68 of the ancient Sanskrit text '' Mānasāra Silpa'' details casting idols in wax and is entitled ''Maduchchhista Vidhānam'', or the "lost wax method". The 12th century text '' Mānasollāsa'', allegedly written by King Someshvara III of theWestern Chalukya Empire

The Western Chalukya Empire ( ) ruled most of the Deccan Plateau, western Deccan, South India, between the 10th and 12th centuries. This Kannada dynasty is sometimes called the ''Kalyani Chalukya'' after its regal capital at Kalyani, today's ...

, also provides detail about lost-wax and other casting processes.

In a 16th-century treatise, the '' Uttarabhaga'' of the Śilparatna written by Srïkumāra, verses 32 to 52 of Chapter 2 ("''Linga Lakshanam''"), give detailed instructions on making a hollow casting.

Theophilus

An early medieval writer Theophilus Presbyter, believed to be theBenedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

monk and metalworker Roger of Helmarshausen, wrote a treatise in the early-to-mid-12th century that includes original work and copied information from other sources, such as the '' Mappae clavicula'' and Eraclius, ''De dolorous et artibus Romanorum''. It provides step-by-step procedures for making various articles, some by lost-wax casting: "The Copper Wind Chest and Its Conductor" (Chapter 84); "Tin Cruets" (Chapter 88), and "Casting Bells" (Chapter 85), which call for using "tallow" instead of wax; and "The Cast Censer". In Chapters 86 and 87 Theophilus details how to divide the wax into differing ratio

In mathematics, a ratio () shows how many times one number contains another. For example, if there are eight oranges and six lemons in a bowl of fruit, then the ratio of oranges to lemons is eight to six (that is, 8:6, which is equivalent to the ...

s before moulding and casting to achieve accurately tuned small musical bells. The 16th-century Florentine sculptor Benvenuto Cellini may have used Theophilus' writings when he cast his bronze '' Perseus with the Head of Medusa''.

America

The Spanish writer Releigh (1596) in brief account refers toAztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

casting.

Gallery

See also

* Fusible core injection moldingReferences

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Lost-Wax Casting 5th-millennium BC introductions Casting (manufacturing) Jewellery making Sculpture techniques Archaeology of material culture Copying Archaeometallurgy