Deoxygenated Hemoglobin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a

In 1825, Johann Friedrich Engelhart discovered that the ratio of iron to protein is identical in the hemoglobins of several species. From the known atomic mass of iron, he calculated the molecular mass of hemoglobin to ''n'' × 16000 (''n''=number of iron atoms per hemoglobin molecule, now known to be 4), the first determination of a protein's molecular mass. This "hasty conclusion" drew ridicule from colleagues who could not believe that any molecule could be so large. However, Gilbert Smithson Adair confirmed Engelhart's results in 1925 by measuring the osmotic pressure of hemoglobin solutions.

Although blood had been known to carry oxygen since at least 1794, the oxygen-carrying property of hemoglobin was described by Hünefeld in 1840. In 1851, German physiologist Otto Funke published a series of articles in which he described growing hemoglobin crystals by successively diluting red blood cells with a solvent such as pure water, alcohol or ether, followed by slow evaporation of the solvent from the resulting protein solution. Hemoglobin's reversible oxygenation was described a few years later by Felix Hoppe-Seyler.

With the development of

In 1825, Johann Friedrich Engelhart discovered that the ratio of iron to protein is identical in the hemoglobins of several species. From the known atomic mass of iron, he calculated the molecular mass of hemoglobin to ''n'' × 16000 (''n''=number of iron atoms per hemoglobin molecule, now known to be 4), the first determination of a protein's molecular mass. This "hasty conclusion" drew ridicule from colleagues who could not believe that any molecule could be so large. However, Gilbert Smithson Adair confirmed Engelhart's results in 1925 by measuring the osmotic pressure of hemoglobin solutions.

Although blood had been known to carry oxygen since at least 1794, the oxygen-carrying property of hemoglobin was described by Hünefeld in 1840. In 1851, German physiologist Otto Funke published a series of articles in which he described growing hemoglobin crystals by successively diluting red blood cells with a solvent such as pure water, alcohol or ether, followed by slow evaporation of the solvent from the resulting protein solution. Hemoglobin's reversible oxygenation was described a few years later by Felix Hoppe-Seyler.

With the development of

Variations in hemoglobin sequences, as with other proteins, may be adaptive. For example, hemoglobin has been found to adapt in different ways to the thin air at high altitudes, where lower partial pressure of oxygen diminishes its binding to hemoglobin compared to the higher pressures at sea level. Recent studies of deer mice found mutations in four genes that can account for differences between high- and low-elevation populations. It was found that the genes of the two breeds are "virtually identical—except for those that govern the oxygen-carrying capacity of their hemoglobin. . . . The genetic difference enables highland mice to make more efficient use of their oxygen."

Variations in hemoglobin sequences, as with other proteins, may be adaptive. For example, hemoglobin has been found to adapt in different ways to the thin air at high altitudes, where lower partial pressure of oxygen diminishes its binding to hemoglobin compared to the higher pressures at sea level. Recent studies of deer mice found mutations in four genes that can account for differences between high- and low-elevation populations. It was found that the genes of the two breeds are "virtually identical—except for those that govern the oxygen-carrying capacity of their hemoglobin. . . . The genetic difference enables highland mice to make more efficient use of their oxygen."

Hemoglobin has a quaternary structure characteristic of many multi-subunit globular proteins. Most of the amino acids in hemoglobin form alpha helices, and these helices are connected by short non-helical segments. Hydrogen bonds stabilize the helical sections inside this protein, causing attractions within the molecule, which then causes each polypeptide chain to fold into a specific shape. Hemoglobin's quaternary structure comes from its four subunits in roughly a tetrahedral arrangement.

In most vertebrates, the hemoglobin

Hemoglobin has a quaternary structure characteristic of many multi-subunit globular proteins. Most of the amino acids in hemoglobin form alpha helices, and these helices are connected by short non-helical segments. Hydrogen bonds stabilize the helical sections inside this protein, causing attractions within the molecule, which then causes each polypeptide chain to fold into a specific shape. Hemoglobin's quaternary structure comes from its four subunits in roughly a tetrahedral arrangement.

In most vertebrates, the hemoglobin

MedicineNet. Web. 12 Oct. 2009. The four polypeptide chains are bound to each other by salt bridges,

When oxygen binds to the iron complex, it causes the iron atom to move back toward the center of the plane of the porphyrin ring (see moving diagram). At the same time, the imidazole side-chain of the histidine residue interacting at the other pole of the iron is pulled toward the porphyrin ring. This interaction forces the plane of the ring sideways toward the outside of the tetramer, and also induces a strain in the protein helix containing the histidine as it moves nearer to the iron atom. This strain is transmitted to the remaining three monomers in the tetramer, where it induces a similar conformational change in the other heme sites such that binding of oxygen to these sites becomes easier.

As oxygen binds to one monomer of hemoglobin, the tetramer's conformation shifts from the T (tense) state to the R (relaxed) state. This shift promotes the binding of oxygen to the remaining three monomers' heme groups, thus saturating the hemoglobin molecule with oxygen.

In the tetrameric form of normal adult hemoglobin, the binding of oxygen is, thus, a cooperative process. The binding affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen is increased by the oxygen saturation of the molecule, with the first molecules of oxygen bound influencing the shape of the binding sites for the next ones, in a way favorable for binding. This positive cooperative binding is achieved through steric conformational changes of the hemoglobin protein complex as discussed above; i.e., when one subunit protein in hemoglobin becomes oxygenated, a conformational or structural change in the whole complex is initiated, causing the other subunits to gain an increased affinity for oxygen. As a consequence, the oxygen binding curve of hemoglobin is sigmoidal, or ''S''-shaped, as opposed to the normal

When oxygen binds to the iron complex, it causes the iron atom to move back toward the center of the plane of the porphyrin ring (see moving diagram). At the same time, the imidazole side-chain of the histidine residue interacting at the other pole of the iron is pulled toward the porphyrin ring. This interaction forces the plane of the ring sideways toward the outside of the tetramer, and also induces a strain in the protein helix containing the histidine as it moves nearer to the iron atom. This strain is transmitted to the remaining three monomers in the tetramer, where it induces a similar conformational change in the other heme sites such that binding of oxygen to these sites becomes easier.

As oxygen binds to one monomer of hemoglobin, the tetramer's conformation shifts from the T (tense) state to the R (relaxed) state. This shift promotes the binding of oxygen to the remaining three monomers' heme groups, thus saturating the hemoglobin molecule with oxygen.

In the tetrameric form of normal adult hemoglobin, the binding of oxygen is, thus, a cooperative process. The binding affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen is increased by the oxygen saturation of the molecule, with the first molecules of oxygen bound influencing the shape of the binding sites for the next ones, in a way favorable for binding. This positive cooperative binding is achieved through steric conformational changes of the hemoglobin protein complex as discussed above; i.e., when one subunit protein in hemoglobin becomes oxygenated, a conformational or structural change in the whole complex is initiated, causing the other subunits to gain an increased affinity for oxygen. As a consequence, the oxygen binding curve of hemoglobin is sigmoidal, or ''S''-shaped, as opposed to the normal

Hence, blood with high carbon dioxide levels is also lower in pH (more

Hence, blood with high carbon dioxide levels is also lower in pH (more

Abnormal forms that occur in diseases:

* Hemoglobin D – (α2βD2) – A variant form of hemoglobin.

* Hemoglobin H (β4) – A variant form of hemoglobin, formed by a tetramer of β chains, which may be present in variants of α thalassemia.

* Hemoglobin Barts (γ4) – A variant form of hemoglobin, formed by a tetramer of γ chains, which may be present in variants of α thalassemia.

* Hemoglobin S (α2βS2) – A variant form of hemoglobin found in people with sickle cell disease. There is a variation in the β-chain gene, causing a change in the properties of hemoglobin, which results in sickling of red blood cells.

* Hemoglobin C (α2βC2) – Another variant due to a variation in the β-chain gene. This variant causes a mild chronic hemolytic anemia.

* Hemoglobin E (α2βE2) – Another variant due to a variation in the β-chain gene. This variant causes a mild chronic hemolytic anemia.

* Hemoglobin AS – A heterozygous form causing sickle cell trait with one adult gene and one sickle cell disease gene

* Hemoglobin SC disease – A compound heterozygous form with one sickle gene and another encoding hemoglobin C.

* Hemoglobin Hopkins-2 – A variant form of hemoglobin that is sometimes viewed in combination with hemoglobin S to produce sickle cell disease.

Abnormal forms that occur in diseases:

* Hemoglobin D – (α2βD2) – A variant form of hemoglobin.

* Hemoglobin H (β4) – A variant form of hemoglobin, formed by a tetramer of β chains, which may be present in variants of α thalassemia.

* Hemoglobin Barts (γ4) – A variant form of hemoglobin, formed by a tetramer of γ chains, which may be present in variants of α thalassemia.

* Hemoglobin S (α2βS2) – A variant form of hemoglobin found in people with sickle cell disease. There is a variation in the β-chain gene, causing a change in the properties of hemoglobin, which results in sickling of red blood cells.

* Hemoglobin C (α2βC2) – Another variant due to a variation in the β-chain gene. This variant causes a mild chronic hemolytic anemia.

* Hemoglobin E (α2βE2) – Another variant due to a variation in the β-chain gene. This variant causes a mild chronic hemolytic anemia.

* Hemoglobin AS – A heterozygous form causing sickle cell trait with one adult gene and one sickle cell disease gene

* Hemoglobin SC disease – A compound heterozygous form with one sickle gene and another encoding hemoglobin C.

* Hemoglobin Hopkins-2 – A variant form of hemoglobin that is sometimes viewed in combination with hemoglobin S to produce sickle cell disease.

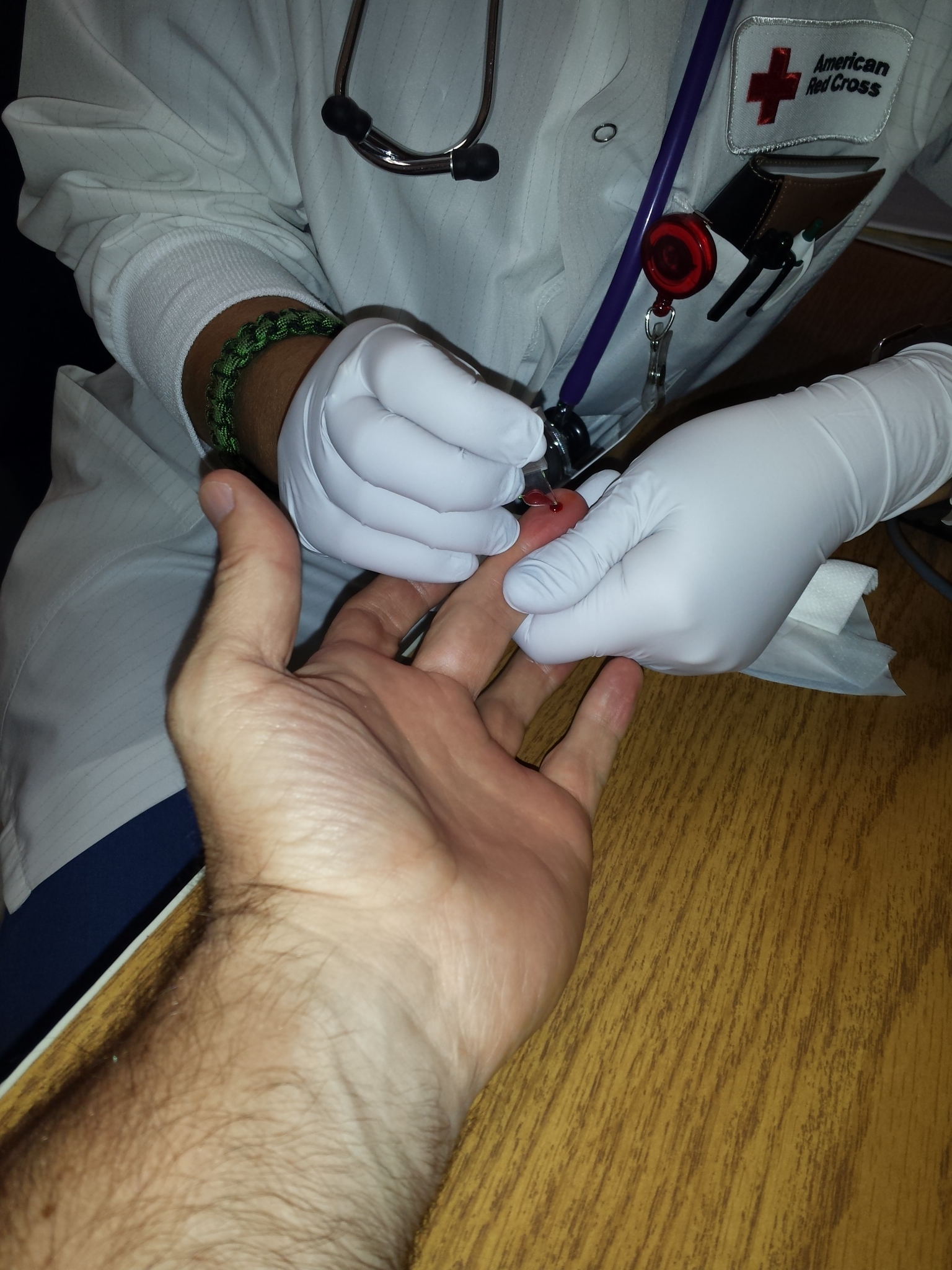

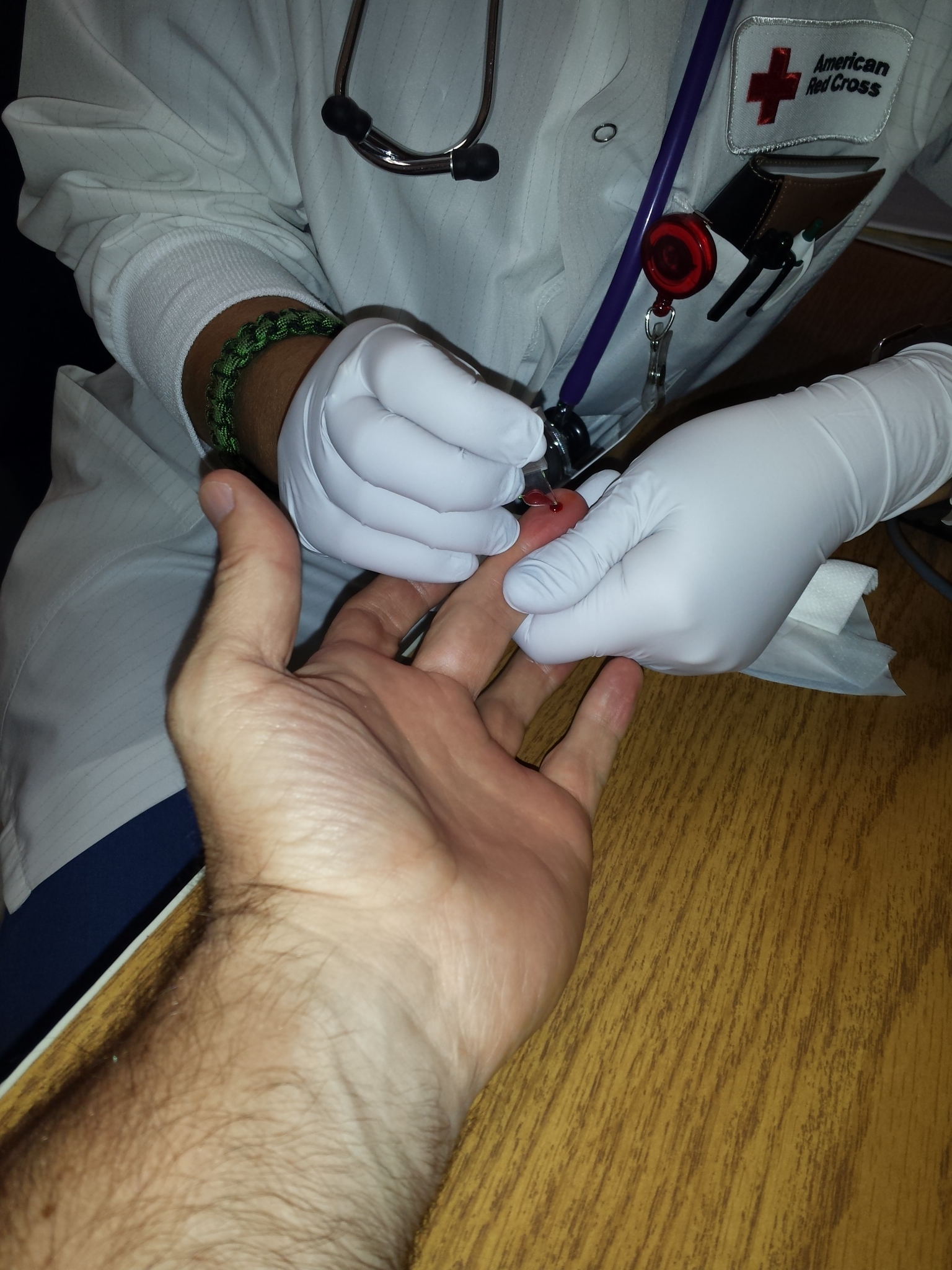

Hemoglobin concentration measurement is among the most commonly performed

Hemoglobin concentration measurement is among the most commonly performed

The structure of hemoglobins varies across species. Hemoglobin occurs in all kingdoms of organisms, but not in all organisms. Primitive species such as bacteria, protozoa,

The structure of hemoglobins varies across species. Hemoglobin occurs in all kingdoms of organisms, but not in all organisms. Primitive species such as bacteria, protozoa,

National Anemia Action Council

a

anemia.org

a

www.life-of-science.net

Animation of hemoglobin: from deoxy to oxy form

a

vimeo.com

{{Authority control Hemoglobins Equilibrium chemistry Respiratory physiology

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

containing iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

that facilitates the transportation of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

in red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s. Almost all vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin in the blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is com ...

carries oxygen from the respiratory organs (lung

The lungs are the primary Organ (biology), organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the Vertebral column, backbone on either side of the heart. Their ...

s or gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

s) to the other tissues of the body, where it releases the oxygen to enable aerobic respiration

Cellular respiration is the process of oxidizing biological fuels using an inorganic electron acceptor, such as oxygen, to drive production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which stores chemical energy in a biologically accessible form. Cellu ...

which powers an animal's metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

. A healthy human has 12to 20grams of hemoglobin in every 100mL of blood. Hemoglobin is a metalloprotein, a chromoprotein A chromoprotein is a conjugated protein that contains a pigmented prosthetic group (or cofactor). A common example is haemoglobin, which contains a heme cofactor, which is the iron-containing molecule that makes Hemoglobin#Oxyhemoglobin, oxygenated ...

, and a globulin.

In mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, hemoglobin makes up about 96% of a red blood cell's dry weight (excluding water), and around 35% of the total weight (including water). Hemoglobin has an oxygen-binding capacity of 1.34mL of O2 per gram, which increases the total blood oxygen capacity

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is compo ...

seventy-fold compared to dissolved oxygen in blood plasma alone. The mammalian hemoglobin molecule can bind and transport up to four oxygen molecules.

Hemoglobin also transports other gases. It carries off some of the body's respiratory carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

(about 20–25% of the total) as carbaminohemoglobin

Carbaminohemoglobin (carbaminohaemoglobin BrE) (CO2Hb, also known as carbhemoglobin and carbohemoglobin) is a Chemical compound, compound of hemoglobin and carbon dioxide, and is one of the forms in which carbon dioxide exists in the blood. In bl ...

, in which CO2 binds to the heme protein

A hemeprotein (or haemprotein; also hemoprotein or haemoprotein), or heme protein, is a protein that contains a heme prosthetic group. They are a very large class of metalloproteins. The heme group confers functionality, which can include oxyg ...

. The molecule also carries the important regulatory molecule nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide, nitrogen monooxide, or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes den ...

bound to a thiol group in the globin protein, releasing it at the same time as oxygen.

Hemoglobin is also found in other cells, including in the A9 dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra

The substantia nigra (SN) is a basal ganglia structure located in the midbrain that plays an important role in reward and movement. ''Substantia nigra'' is Latin for "black substance", reflecting the fact that parts of the substantia nigra a ...

, macrophage

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

s, alveolar cells, lungs, retinal pigment epithelium, hepatocytes, mesangial cell

Mesangial cells are specialised cells in the kidney that make up the mesangium of the glomerulus. Together with the mesangial matrix, they form the vascular pole of the renal corpuscle. The mesangial cell population accounts for approximately ...

s of the kidney, endometrial cells, cervical cells, and vaginal epithelial cells. In these tissues, hemoglobin absorbs unneeded oxygen as an antioxidant

Antioxidants are Chemical compound, compounds that inhibit Redox, oxidation, a chemical reaction that can produce Radical (chemistry), free radicals. Autoxidation leads to degradation of organic compounds, including living matter. Antioxidants ...

, and regulates iron metabolism. Excessive glucose in the blood can attach to hemoglobin and raise the level of hemoglobin A1c.

Hemoglobin and hemoglobin-like molecules are also found in many invertebrates, fungi, and plants. In these organisms, hemoglobins may carry oxygen, or they may transport and regulate other small molecules and ions such as carbon dioxide, nitric oxide, hydrogen sulfide and sulfide. A variant called leghemoglobin serves to scavenge oxygen away from anaerobic systems such as the nitrogen-fixing nodules of leguminous plants, preventing oxygen poisoning.

The medical condition hemoglobinemia, a form of anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

, is caused by intravascular hemolysis, in which hemoglobin leaks from red blood cells into the blood plasma

Blood plasma is a light Amber (color), amber-colored liquid component of blood in which blood cells are absent, but which contains Blood protein, proteins and other constituents of whole blood in Suspension (chemistry), suspension. It makes up ...

.

Research history

In 1825, Johann Friedrich Engelhart discovered that the ratio of iron to protein is identical in the hemoglobins of several species. From the known atomic mass of iron, he calculated the molecular mass of hemoglobin to ''n'' × 16000 (''n''=number of iron atoms per hemoglobin molecule, now known to be 4), the first determination of a protein's molecular mass. This "hasty conclusion" drew ridicule from colleagues who could not believe that any molecule could be so large. However, Gilbert Smithson Adair confirmed Engelhart's results in 1925 by measuring the osmotic pressure of hemoglobin solutions.

Although blood had been known to carry oxygen since at least 1794, the oxygen-carrying property of hemoglobin was described by Hünefeld in 1840. In 1851, German physiologist Otto Funke published a series of articles in which he described growing hemoglobin crystals by successively diluting red blood cells with a solvent such as pure water, alcohol or ether, followed by slow evaporation of the solvent from the resulting protein solution. Hemoglobin's reversible oxygenation was described a few years later by Felix Hoppe-Seyler.

With the development of

In 1825, Johann Friedrich Engelhart discovered that the ratio of iron to protein is identical in the hemoglobins of several species. From the known atomic mass of iron, he calculated the molecular mass of hemoglobin to ''n'' × 16000 (''n''=number of iron atoms per hemoglobin molecule, now known to be 4), the first determination of a protein's molecular mass. This "hasty conclusion" drew ridicule from colleagues who could not believe that any molecule could be so large. However, Gilbert Smithson Adair confirmed Engelhart's results in 1925 by measuring the osmotic pressure of hemoglobin solutions.

Although blood had been known to carry oxygen since at least 1794, the oxygen-carrying property of hemoglobin was described by Hünefeld in 1840. In 1851, German physiologist Otto Funke published a series of articles in which he described growing hemoglobin crystals by successively diluting red blood cells with a solvent such as pure water, alcohol or ether, followed by slow evaporation of the solvent from the resulting protein solution. Hemoglobin's reversible oxygenation was described a few years later by Felix Hoppe-Seyler.

With the development of X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science of determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to Diffraction, diffract in specific directions. By measuring th ...

, it became possible to solve protein structures. In 1959, Max Perutz determined the molecular structure of hemoglobin. For this work he shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

with John Kendrew, who sequenced the globular protein myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle, skeletal Muscle, muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compar ...

.

The role of hemoglobin in the blood was elucidated by French physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out chemical and ...

Claude Bernard.

The name ''hemoglobin'' (or ''haemoglobin'') is derived from the words ''heme

Heme (American English), or haem (Commonwealth English, both pronounced /Help:IPA/English, hi:m/ ), is a ring-shaped iron-containing molecule that commonly serves as a Ligand (biochemistry), ligand of various proteins, more notably as a Prostheti ...

'' (or '' haem'') and ''globin

The globins are a superfamily of heme-containing globular proteins, involved in binding and/or transporting oxygen. These proteins all incorporate the globin fold, a series of eight alpha helical segments. Two prominent members include myo ...

'', reflecting the fact that each subunit of hemoglobin is a globular protein with an embedded heme

Heme (American English), or haem (Commonwealth English, both pronounced /Help:IPA/English, hi:m/ ), is a ring-shaped iron-containing molecule that commonly serves as a Ligand (biochemistry), ligand of various proteins, more notably as a Prostheti ...

group. Each heme group contains one iron atom, that can bind one oxygen molecule through ion-induced dipole forces. The most common type of hemoglobin in mammals contains four such subunits.

Genetics

Hemoglobin consists of protein subunits (globin

The globins are a superfamily of heme-containing globular proteins, involved in binding and/or transporting oxygen. These proteins all incorporate the globin fold, a series of eight alpha helical segments. Two prominent members include myo ...

molecules), which are polypeptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty ...

s, long folded chains of specific amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s which determine the protein's chemical properties and function. The amino acid sequence of any polypeptide is translated from a segment of DNA, the corresponding gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

.

There is more than one hemoglobin gene. In humans, hemoglobin A (the main form of hemoglobin in adults) is coded by genes ''HBA1

Hemoglobin subunit alpha, Hemoglobin, alpha 1, is a hemoglobin protein that in humans is encoded by the ''HBA1'' gene.

Gene

The human alpha globin gene cluster located on chromosome 16 spans about 30 kb and includes seven loci: 5'- zeta - pse ...

'', ''HBA2

Hemoglobin, alpha 2 also known as ''HBA2'' is a gene that in humans codes for the alpha globin chain of hemoglobin.

Function

The human alpha globin gene cluster is located on chromosome 16 and spans about 30 kb, including seven alpha like glo ...

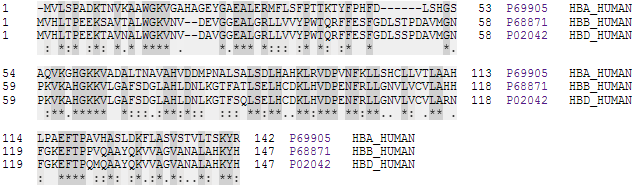

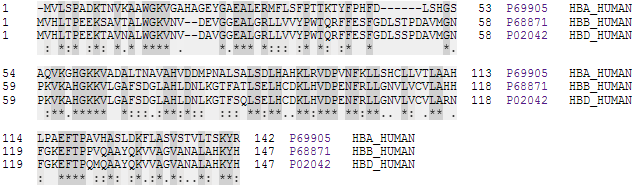

'', and '' HBB''. Alpha 1 and alpha 2 subunits are respectively coded by genes ''HBA1'' and ''HBA2'' close together on chromosome 16, while the beta subunit is coded by gene ''HBB'' on chromosome 11. The amino acid sequences of the globin subunits usually differ between species, with the difference growing with evolutionary distance. For example, the most common hemoglobin sequences in humans, bonobos and chimpanzees are completely identical, with exactly the same alpha and beta globin protein chains. Human and gorilla hemoglobin differ in one amino acid in both alpha and beta chains, and these differences grow larger between less closely related species.

Mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s in the genes for hemoglobin can result in variants of hemoglobin within a single species, although one sequence is usually "most common" in each species. Many of these mutations cause no disease, but some cause a group of hereditary diseases called '' hemoglobinopathies''. The best known hemoglobinopathy is sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD), also simply called sickle cell, is a group of inherited haemoglobin-related blood disorders. The most common type is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying ...

, which was the first human disease whose mechanism

Mechanism may refer to:

*Mechanism (economics), a set of rules for a game designed to achieve a certain outcome

**Mechanism design, the study of such mechanisms

*Mechanism (engineering), rigid bodies connected by joints in order to accomplish a ...

was understood at the molecular level. A mostly separate set of diseases called thalassemia

Thalassemias are a group of Genetic disorder, inherited blood disorders that manifest as the production of reduced hemoglobin. Symptoms depend on the type of thalassemia and can vary from none to severe, including death. Often there is mild to ...

s involves underproduction of normal and sometimes abnormal hemoglobins, through problems and mutations in globin gene regulation. All these diseases produce anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

.

Variations in hemoglobin sequences, as with other proteins, may be adaptive. For example, hemoglobin has been found to adapt in different ways to the thin air at high altitudes, where lower partial pressure of oxygen diminishes its binding to hemoglobin compared to the higher pressures at sea level. Recent studies of deer mice found mutations in four genes that can account for differences between high- and low-elevation populations. It was found that the genes of the two breeds are "virtually identical—except for those that govern the oxygen-carrying capacity of their hemoglobin. . . . The genetic difference enables highland mice to make more efficient use of their oxygen."

Variations in hemoglobin sequences, as with other proteins, may be adaptive. For example, hemoglobin has been found to adapt in different ways to the thin air at high altitudes, where lower partial pressure of oxygen diminishes its binding to hemoglobin compared to the higher pressures at sea level. Recent studies of deer mice found mutations in four genes that can account for differences between high- and low-elevation populations. It was found that the genes of the two breeds are "virtually identical—except for those that govern the oxygen-carrying capacity of their hemoglobin. . . . The genetic difference enables highland mice to make more efficient use of their oxygen." Mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

hemoglobin featured mutations that allowed for oxygen delivery at lower temperatures, thus enabling mammoths to migrate to higher latitudes during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

. This was also found in hummingbirds that inhabit the Andes. Hummingbirds already expend a lot of energy and thus have high oxygen demands and yet Andean hummingbirds have been found to thrive in high altitudes. Non-synonymous mutations in the hemoglobin gene of multiple species living at high elevations (''Oreotrochilus, A. castelnaudii, C. violifer, P. gigas,'' and ''A. viridicuada'') have caused the protein to have less of an affinity for inositol hexaphosphate (IHP), a molecule found in birds that has a similar role as 2,3-BPG in humans; this results in the ability to bind oxygen in lower partial pressures.

Birds' unique circulatory lungs also promote efficient use of oxygen at low partial pressures of O2. These two adaptations reinforce each other and account for birds' remarkable high-altitude performance.

Hemoglobin adaptation extends to humans, as well. There is a higher offspring survival rate among Tibetan women with high oxygen saturation genotypes residing at 4,000 m. Natural selection seems to be the main force working on this gene because the mortality rate of offspring is significantly lower for women with higher hemoglobin-oxygen affinity when compared to the mortality rate of offspring from women with low hemoglobin-oxygen affinity. While the exact genotype and mechanism by which this occurs is not yet clear, selection is acting on these women's ability to bind oxygen in low partial pressures, which overall allows them to better sustain crucial metabolic processes.

Synthesis

Hemoglobin (Hb) is synthesized in a complex series of steps. The heme part is synthesized in a series of steps in themitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

and the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells ( intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

of immature red blood cells, while the globin

The globins are a superfamily of heme-containing globular proteins, involved in binding and/or transporting oxygen. These proteins all incorporate the globin fold, a series of eight alpha helical segments. Two prominent members include myo ...

protein parts are synthesized by ribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

s in the cytosol. Production of Hb continues in the cell throughout its early development from the proerythroblast to the reticulocyte in the bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid biological tissue, tissue found within the Spongy bone, spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It i ...

. At this point, the nucleus is lost in mammalian red blood cells, but not in bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s and many other species. Even after the loss of the nucleus in mammals, residual ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

allows further synthesis of Hb until the reticulocyte loses its RNA soon after entering the vasculature (this hemoglobin-synthetic RNA in fact gives the reticulocyte its reticulated appearance and name).

Structure of heme

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

is an assembly of four globular protein subunits. Each subunit is composed of a protein chain tightly associated with a non-protein prosthetic

In medicine, a prosthesis (: prostheses; from ), or a prosthetic implant, is an artificial device that replaces a missing body part, which may be lost through physical trauma, disease, or a condition present at birth (Congenital, congenital disord ...

heme

Heme (American English), or haem (Commonwealth English, both pronounced /Help:IPA/English, hi:m/ ), is a ring-shaped iron-containing molecule that commonly serves as a Ligand (biochemistry), ligand of various proteins, more notably as a Prostheti ...

group. Each protein chain arranges into a set of alpha-helix structural segments connected together in a globin fold arrangement. Such a name is given because this arrangement is the same folding motif used in other heme/globin proteins such as myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle, skeletal Muscle, muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compar ...

. This folding pattern contains a pocket that strongly binds the heme group.

A heme group consists of an iron (Fe) ion held in a heterocyclic ring, known as a porphyrin. This porphyrin ring consists of four pyrrole molecules cyclically linked together (by methine bridges) with the iron ion bound in the center. The iron ion, which is the site of oxygen binding, coordinates with the four nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

atoms in the center of the ring, which all lie in one plane. The heme is bound strongly (covalently) to the globular protein via the N atoms of the imidazole ring of F8 histidine

Histidine (symbol His or H) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an Amine, α-amino group (which is in the protonated –NH3+ form under Physiological condition, biological conditions), a carboxylic ...

residue (also known as the proximal histidine) below the porphyrin ring. A sixth position can reversibly bind oxygen by a coordinate covalent bond

In coordination chemistry, a coordinate covalent bond, also known as a dative bond, dipolar bond, or coordinate bond is a kind of two-center, two-electron covalent bond in which the two electrons derive from the same atom. The bonding of metal i ...

, completing the octahedral group of six ligands. This reversible bonding with oxygen is why hemoglobin is so useful for transporting oxygen around the body. Oxygen binds in an "end-on bent" geometry where one oxygen atom binds to Fe and the other protrudes at an angle. When oxygen is not bound, a very weakly bonded water molecule fills the site, forming a distorted octahedron

In geometry, an octahedron (: octahedra or octahedrons) is any polyhedron with eight faces. One special case is the regular octahedron, a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at each vertex. Many types of i ...

.

Even though carbon dioxide is carried by hemoglobin, it does not compete with oxygen for the iron-binding positions but is bound to the amine groups of the protein chains attached to the heme groups.

The iron ion may be either in the ferrous Fe2+ or in the ferric Fe3+ state, but ferrihemoglobin (methemoglobin

Methemoglobin (British: methaemoglobin, shortened MetHb) (pronounced "met-hemoglobin") is a hemoglobin ''in the form of metalloprotein'', in which the iron in the heme group is in the Fe3+ (ferric) state, not the Fe2+ (ferrous) of normal hemoglobin ...

) (Fe3+) cannot bind oxygen. In binding, oxygen temporarily and reversibly oxidizes (Fe2+) to (Fe3+) while oxygen temporarily turns into the superoxide

In chemistry, a superoxide is a compound that contains the superoxide ion, which has the chemical formula . The systematic name of the anion is dioxide(1−). The reactive oxygen ion superoxide is particularly important as the product of t ...

ion, thus iron must exist in the +2 oxidation state to bind oxygen. If superoxide ion associated to Fe3+ is protonated, the hemoglobin iron will remain oxidized and incapable of binding oxygen. In such cases, the enzyme methemoglobin reductase will be able to eventually reactivate methemoglobin by reducing the iron center.

In adult humans, the most common hemoglobin type is a tetramer (which contains four subunit proteins) called ''hemoglobin A'', consisting of two α and two β subunits non-covalently bound, each made of 141 and 146 amino acid residues, respectively. This is denoted as α2β2. The subunits are structurally similar and about the same size. Each subunit has a molecular weight of about 16,000 daltons, for a total molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

of the tetramer of about 64,000 daltons (64,458 g/mol). Thus, 1 g/dL=0.1551 mmol/L. Hemoglobin A is the most intensively studied of the hemoglobin molecules.

In human infants, the fetal hemoglobin molecule is made up of 2 α chains and 2 γ chains. The γ chains are gradually replaced by β chains as the infant grows."Hemoglobin."MedicineNet. Web. 12 Oct. 2009. The four polypeptide chains are bound to each other by salt bridges,

hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s, and the hydrophobic effect.

Oxygen saturation

In general, hemoglobin can be saturated with oxygen molecules (oxyhemoglobin), or desaturated with oxygen molecules (deoxyhemoglobin).Oxyhemoglobin

''Oxyhemoglobin'' is formed during physiological respiration when oxygen binds to the heme component of the protein hemoglobin in red blood cells. This process occurs in the pulmonary capillaries adjacent to the alveoli of the lungs. The oxygen then travels through the blood stream to be dropped off at cells where it is utilized as a terminal electron acceptor in the production of ATP by the process ofoxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation(UK , US : or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation, is the metabolic pathway in which Cell (biology), cells use enzymes to Redox, oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order ...

. It does not, however, help to counteract a decrease in blood pH. Ventilation

Ventilation may refer to:

* Ventilation (physiology), the movement of air between the environment and the lungs via inhalation and exhalation

** Mechanical ventilation, in medicine, using artificial methods to assist breathing

*** Respirator, a ma ...

, or breathing, may reverse this condition by removal of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

, thus causing a shift up in pH.

Hemoglobin exists in two forms, a ''taut (tense) form'' (T) and a ''relaxed form'' (R). Various factors such as low pH, high CO2 and high 2,3 BPG at the level of the tissues favor the taut form, which has low oxygen affinity and releases oxygen in the tissues. Conversely, a high pH, low CO2, or low 2,3 BPG favors the relaxed form, which can better bind oxygen. The partial pressure of the system also affects O2 affinity where, at high partial pressures of oxygen (such as those present in the alveoli), the relaxed (high affinity, R) state is favoured. Inversely, at low partial pressures (such as those present in respiring tissues), the (low affinity, T) tense state is favoured. Additionally, the binding of oxygen to the iron(II) heme pulls the iron into the plane of the porphyrin ring, causing a slight conformational shift. The shift encourages oxygen to bind to the three remaining heme units within hemoglobin (thus, oxygen binding is cooperative).

Classically, the iron in oxyhemoglobin is seen as existing in the iron(II) oxidation state. However, the complex of oxygen with heme iron is diamagnetic

Diamagnetism is the property of materials that are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagn ...

, whereas both oxygen and high-spin iron(II) are paramagnetic. Experimental evidence strongly suggests heme iron is in the iron(III) oxidation state in oxyhemoglobin, with the oxygen existing as superoxide anion (O2•−) or in a covalent charge-transfer complex.

Deoxygenated hemoglobin

Deoxygenated hemoglobin (deoxyhemoglobin) is the form of hemoglobin without the bound oxygen. The absorption spectra of oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin differ. The oxyhemoglobin has significantly lower absorption of the 660 nmwavelength

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same ''phase (waves ...

than deoxyhemoglobin, while at 940 nm its absorption is slightly higher. This difference is used for the measurement of the amount of oxygen in a patient's blood by an instrument called a pulse oximeter. This difference also accounts for the presentation of cyanosis

Cyanosis is the change of Tissue (biology), tissue color to a bluish-purple hue, as a result of decrease in the amount of oxygen bound to the hemoglobin in the red blood cells of the capillary bed. Cyanosis is apparent usually in the Tissue (bi ...

, the blue to purplish color that tissues develop during hypoxia.

Deoxygenated hemoglobin is paramagnetic; it is weakly attracted to magnetic field

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular ...

s. In contrast, oxygenated hemoglobin exhibits diamagnetism

Diamagnetism is the property of materials that are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagnet ...

, a weak repulsion from a magnetic field.

Evolution of vertebrate hemoglobin

Scientists agree that the event that separated myoglobin from hemoglobin occurred afterlamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are a group of Agnatha, jawless fish comprising the order (biology), order Petromyzontiformes , sole order in the Class (biology), class Petromyzontida. The adult lamprey is characterize ...

s diverged from jawed vertebrates. This separation of myoglobin and hemoglobin allowed for the different functions of the two molecules to arise and develop: myoglobin has more to do with oxygen storage while hemoglobin is tasked with oxygen transport. The α- and β-like globin genes encode the individual subunits of the protein. The predecessors of these genes arose through another duplication event also after the gnathosome common ancestor derived from jawless fish, approximately 450–500 million years ago. Ancestral reconstruction studies suggest that the preduplication ancestor of the α and β genes was a dimer made up of identical globin subunits, which then evolved to assemble into a tetrameric architecture after the duplication. The development of α and β genes created the potential for hemoglobin to be composed of multiple distinct subunits, a physical composition central to hemoglobin's ability to transport oxygen. Having multiple subunits contributes to hemoglobin's ability to bind oxygen cooperatively as well as be regulated allosterically. Subsequently, the α gene also underwent a duplication event to form the ''HBA1'' and ''HBA2'' genes. These further duplications and divergences have created a diverse range of α- and β-like globin genes that are regulated so that certain forms occur at different stages of development.

Most ice fish of the family Channichthyidae have lost their hemoglobin genes as an adaptation to cold water.

Cooperativity

When oxygen binds to the iron complex, it causes the iron atom to move back toward the center of the plane of the porphyrin ring (see moving diagram). At the same time, the imidazole side-chain of the histidine residue interacting at the other pole of the iron is pulled toward the porphyrin ring. This interaction forces the plane of the ring sideways toward the outside of the tetramer, and also induces a strain in the protein helix containing the histidine as it moves nearer to the iron atom. This strain is transmitted to the remaining three monomers in the tetramer, where it induces a similar conformational change in the other heme sites such that binding of oxygen to these sites becomes easier.

As oxygen binds to one monomer of hemoglobin, the tetramer's conformation shifts from the T (tense) state to the R (relaxed) state. This shift promotes the binding of oxygen to the remaining three monomers' heme groups, thus saturating the hemoglobin molecule with oxygen.

In the tetrameric form of normal adult hemoglobin, the binding of oxygen is, thus, a cooperative process. The binding affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen is increased by the oxygen saturation of the molecule, with the first molecules of oxygen bound influencing the shape of the binding sites for the next ones, in a way favorable for binding. This positive cooperative binding is achieved through steric conformational changes of the hemoglobin protein complex as discussed above; i.e., when one subunit protein in hemoglobin becomes oxygenated, a conformational or structural change in the whole complex is initiated, causing the other subunits to gain an increased affinity for oxygen. As a consequence, the oxygen binding curve of hemoglobin is sigmoidal, or ''S''-shaped, as opposed to the normal

When oxygen binds to the iron complex, it causes the iron atom to move back toward the center of the plane of the porphyrin ring (see moving diagram). At the same time, the imidazole side-chain of the histidine residue interacting at the other pole of the iron is pulled toward the porphyrin ring. This interaction forces the plane of the ring sideways toward the outside of the tetramer, and also induces a strain in the protein helix containing the histidine as it moves nearer to the iron atom. This strain is transmitted to the remaining three monomers in the tetramer, where it induces a similar conformational change in the other heme sites such that binding of oxygen to these sites becomes easier.

As oxygen binds to one monomer of hemoglobin, the tetramer's conformation shifts from the T (tense) state to the R (relaxed) state. This shift promotes the binding of oxygen to the remaining three monomers' heme groups, thus saturating the hemoglobin molecule with oxygen.

In the tetrameric form of normal adult hemoglobin, the binding of oxygen is, thus, a cooperative process. The binding affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen is increased by the oxygen saturation of the molecule, with the first molecules of oxygen bound influencing the shape of the binding sites for the next ones, in a way favorable for binding. This positive cooperative binding is achieved through steric conformational changes of the hemoglobin protein complex as discussed above; i.e., when one subunit protein in hemoglobin becomes oxygenated, a conformational or structural change in the whole complex is initiated, causing the other subunits to gain an increased affinity for oxygen. As a consequence, the oxygen binding curve of hemoglobin is sigmoidal, or ''S''-shaped, as opposed to the normal hyperbolic

Hyperbolic may refer to:

* of or pertaining to a hyperbola, a type of smooth curve lying in a plane in mathematics

** Hyperbolic geometry, a non-Euclidean geometry

** Hyperbolic functions, analogues of ordinary trigonometric functions, defined u ...

curve associated with noncooperative binding.

The dynamic mechanism of the cooperativity in hemoglobin and its relation with low-frequency resonance

Resonance is a phenomenon that occurs when an object or system is subjected to an external force or vibration whose frequency matches a resonant frequency (or resonance frequency) of the system, defined as a frequency that generates a maximu ...

has been discussed.

Binding of ligands other than oxygen

Besides the oxygenligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's el ...

, which binds to hemoglobin in a cooperative manner, hemoglobin ligands also include competitive inhibitors such as carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

(CO) and allosteric ligands such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide, nitrogen monooxide, or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes den ...

(NO). The carbon dioxide is bound to amino groups of the globin proteins to form carbaminohemoglobin

Carbaminohemoglobin (carbaminohaemoglobin BrE) (CO2Hb, also known as carbhemoglobin and carbohemoglobin) is a Chemical compound, compound of hemoglobin and carbon dioxide, and is one of the forms in which carbon dioxide exists in the blood. In bl ...

; this mechanism is thought to account for about 10% of carbon dioxide transport in mammals. Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide, nitrogen monooxide, or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes den ...

can also be transported by hemoglobin; it is bound to specific thiol groups in the globin protein to form an S-nitrosothiol, which dissociates into free nitric oxide and thiol again, as the hemoglobin releases oxygen from its heme site. This nitric oxide transport to peripheral tissues is hypothesized to assist oxygen transport in tissues, by releasing vasodilatory nitric oxide to tissues in which oxygen levels are low.

Competitive

The binding of oxygen is affected by molecules such as carbon monoxide (for example, fromtobacco smoking

Tobacco smoking is the practice of burning tobacco and ingesting the resulting smoke. The smoke may be inhaled, as is done with cigarettes, or released from the mouth, as is generally done with pipes and cigars. The practice is believed to hav ...

, exhaust gas

Exhaust gas or flue gas is emitted as a result of the combustion of fuels such as natural gas, gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, fuel oil, biodiesel blends, or coal. According to the type of engine, it is discharged into the atmosphere through ...

, and incomplete combustion in furnaces). CO competes with oxygen at the heme binding site. Hemoglobin's binding affinity for CO is 250 times greater than its affinity for oxygen. Since carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas, and poses a potentially fatal threat, carbon monoxide detectors have become commercially available to warn of dangerous levels in residences. When hemoglobin combines with CO, it forms a very bright red compound called carboxyhemoglobin

Carboxyhemoglobin (carboxyhaemoglobin BrE) (symbol COHb or HbCO) is a stable complex (chemistry), complex of carbon monoxide and hemoglobin (Hb) that forms in red blood cells upon contact with carbon monoxide. Carboxyhemoglobin is often mistaken ...

, which may cause the skin of CO poisoning victims to appear pink in death, instead of white or blue. When inspired air contains CO levels as low as 0.02%, headache

A headache, also known as cephalalgia, is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of Depression (mood), depression in those with severe ...

and nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. It can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Over 30 d ...

occur; if the CO concentration is increased to 0.1%, unconsciousness will follow. In heavy smokers, up to 20% of the oxygen-active sites can be blocked by CO.

In similar fashion, hemoglobin also has competitive binding affinity for cyanide

In chemistry, cyanide () is an inorganic chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a carbon atom triple-bonded to a nitrogen atom.

Ionic cyanides contain the cyanide anion . This a ...

(CN−), sulfur monoxide (SO), and sulfide

Sulfide (also sulphide in British English) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2− or a compound containing one or more S2− ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to large families o ...

(S2−), including hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

(H2S). All of these bind to iron in heme without changing its oxidation state, but they nevertheless inhibit oxygen-binding, causing grave toxicity.

The iron atom in the heme group must initially be in the ferrous

In chemistry, iron(II) refers to the chemical element, element iron in its +2 oxidation number, oxidation state. The adjective ''ferrous'' or the prefix ''ferro-'' is often used to specify such compounds, as in ''ferrous chloride'' for iron(II ...

(Fe2+) oxidation state to support oxygen and other gases' binding and transport (it temporarily switches to ferric during the time oxygen is bound, as explained above). Initial oxidation to the ferric

In chemistry, iron(III) or ''ferric'' refers to the chemical element, element iron in its +3 oxidation number, oxidation state. ''Ferric chloride'' is an alternative name for iron(III) chloride (). The adjective ''ferrous'' is used instead for i ...

(Fe3+) state without oxygen converts hemoglobin into "hemiglobin" or methemoglobin

Methemoglobin (British: methaemoglobin, shortened MetHb) (pronounced "met-hemoglobin") is a hemoglobin ''in the form of metalloprotein'', in which the iron in the heme group is in the Fe3+ (ferric) state, not the Fe2+ (ferrous) of normal hemoglobin ...

, which cannot bind oxygen. Hemoglobin in normal red blood cells is protected by a reduction system to keep this from happening. Nitric oxide is capable of converting a small fraction of hemoglobin to methemoglobin in red blood cells. The latter reaction is a remnant activity of the more ancient nitric oxide dioxygenase function of globins.

Allosteric

Carbon ''di''oxide occupies a different binding site on the hemoglobin. At tissues, where carbon dioxide concentration is higher, carbon dioxide binds to allosteric site of hemoglobin, facilitating unloading of oxygen from hemoglobin and ultimately its removal from the body after the oxygen has been released to tissues undergoing metabolism. This increased affinity for carbon dioxide by the venous blood is known as the Bohr effect. Through the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, carbon dioxide reacts with water to givecarbonic acid

Carbonic acid is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . The molecule rapidly converts to water and carbon dioxide in the presence of water. However, in the absence of water, it is quite stable at room temperature. The interconversion ...

, which decomposes into bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial bioche ...

and proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

s:

:CO2 + H2O → H2CO3 → HCO3− + H+

acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

ic). Hemoglobin can bind protons and carbon dioxide, which causes a conformational change in the protein and facilitates the release of oxygen. Protons bind at various places on the protein, while carbon dioxide binds at the α-amino group. Carbon dioxide binds to hemoglobin and forms carbaminohemoglobin

Carbaminohemoglobin (carbaminohaemoglobin BrE) (CO2Hb, also known as carbhemoglobin and carbohemoglobin) is a Chemical compound, compound of hemoglobin and carbon dioxide, and is one of the forms in which carbon dioxide exists in the blood. In bl ...

. This decrease in hemoglobin's affinity for oxygen by the binding of carbon dioxide and acid is known as the Bohr effect. The Bohr effect favors the T state rather than the R state. (shifts the O2-saturation curve to the ''right''). Conversely, when the carbon dioxide levels in the blood decrease (i.e., in the lung capillaries), carbon dioxide and protons are released from hemoglobin, increasing the oxygen affinity of the protein. A reduction in the total binding capacity of hemoglobin to oxygen (i.e. shifting the curve down, not just to the right) due to reduced pH is called the root effect. This is seen in bony fish.

It is necessary for hemoglobin to release the oxygen that it binds; if not, there is no point in binding it. The sigmoidal curve of hemoglobin makes it efficient in binding (taking up O2 in lungs), and efficient in unloading (unloading O2 in tissues).

In people acclimated to high altitudes, the concentration of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) in the blood is increased, which allows these individuals to deliver a larger amount of oxygen to tissues under conditions of lower oxygen tension. This phenomenon, where molecule Y affects the binding of molecule X to a transport molecule Z, is called a ''heterotropic'' allosteric effect. Hemoglobin in organisms at high altitudes has also adapted such that it has less of an affinity for 2,3-BPG and so the protein will be shifted more towards its R state. In its R state, hemoglobin will bind oxygen more readily, thus allowing organisms to perform the necessary metabolic processes when oxygen is present at low partial pressures.

Animals other than humans use different molecules to bind to hemoglobin and change its O2 affinity under unfavorable conditions. Fish use both ATP and GTP. These bind to a phosphate "pocket" on the fish hemoglobin molecule, which stabilizes the tense state and therefore decreases oxygen affinity. GTP reduces hemoglobin oxygen affinity much more than ATP, which is thought to be due to an extra hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

formed that further stabilizes the tense state. Under hypoxic conditions, the concentration of both ATP and GTP is reduced in fish red blood cells to increase oxygen affinity.

A variant hemoglobin, called fetal hemoglobin (HbF, α2γ2), is found in the developing fetus

A fetus or foetus (; : fetuses, foetuses, rarely feti or foeti) is the unborn offspring of a viviparous animal that develops from an embryo. Following the embryonic development, embryonic stage, the fetal stage of development takes place. Pren ...

, and binds oxygen with greater affinity than adult hemoglobin. This means that the oxygen binding curve for fetal hemoglobin is left-shifted (i.e., a higher percentage of hemoglobin has oxygen bound to it at lower oxygen tension), in comparison to that of adult hemoglobin. As a result, fetal blood in the placenta

The placenta (: placentas or placentae) is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas, and waste exchange between ...

is able to take oxygen from maternal blood.

Hemoglobin also carries nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide, nitrogen monooxide, or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes den ...

(NO) in the globin part of the molecule. This improves oxygen delivery in the periphery and contributes to the control of respiration. NO binds reversibly to a specific cysteine residue in globin; the binding depends on the state (R or T) of the hemoglobin. The resulting S-nitrosylated hemoglobin influences various NO-related activities such as the control of vascular resistance, blood pressure and respiration. NO is not released in the cytoplasm of red blood cells but transported out of them by an anion exchanger called AE1.

Types of hemoglobin in humans

Hemoglobin variants are a part of the normal embryonic andfetal

A fetus or foetus (; : fetuses, foetuses, rarely feti or foeti) is the unborn offspring of a viviparous animal that develops from an embryo. Following the embryonic stage, the fetal stage of development takes place. Prenatal development is a ...

development. They may also be pathologic mutant forms of hemoglobin in a population

Population is a set of humans or other organisms in a given region or area. Governments conduct a census to quantify the resident population size within a given jurisdiction. The term is also applied to non-human animals, microorganisms, and pl ...

, caused by variations in genetics. Some well-known hemoglobin variants, such as sickle-cell anemia, are responsible for diseases and are considered hemoglobinopathies. Other variants cause no detectable pathology

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

, and are thus considered non-pathological variants.

In embryo

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sp ...

s:

* Gower 1 (ζ2ε2).

* Gower 2 (α2ε2) ().

* Hemoglobin Portland I (ζ2γ2).

* Hemoglobin Portland II (ζ2β2).

In fetuses:

* Hemoglobin F (α2γ2) ().

In neonate

In common terminology, a baby is the very young offspring of adult human beings, while infant (from the Latin word ''infans'', meaning 'baby' or 'child') is a formal or specialised synonym. The terms may also be used to refer to Juvenile (orga ...

s (newborns inmmediately after birth):

* Hemoglobin A (adult hemoglobin) (α2β2) () – The most common with a normal amount over 95%

* Hemoglobin A2 (α2δ2) – δ chain synthesis begins late in the third trimester and, in adults, it has a normal range of 1.5–3.5%

* Hemoglobin F (fetal hemoglobin) (α2γ2) – In adults Hemoglobin F is restricted to a limited population of red cells called F-cells. However, the level of Hb F can be elevated in persons with sickle-cell disease and beta-thalassemia.

Degradation in vertebrate animals

Whenred blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s reach the end of their life due to aging or defects, they are removed from the circulation by the phagocytic activity of macrophages in the spleen or the liver or hemolyze within the circulation. Free hemoglobin is then cleared from the circulation via the hemoglobin transporter CD163, which is exclusively expressed on monocytes or macrophages. Within these cells the hemoglobin molecule is broken up, and the iron gets recycled. This process also produces one molecule of carbon monoxide for every molecule of heme degraded. Heme degradation is the only natural source of carbon monoxide in the human body, and is responsible for the normal blood levels of carbon monoxide in people breathing normal air.

The other major final product of heme degradation is bilirubin

Bilirubin (BR) (adopted from German, originally bili—bile—plus ruber—red—from Latin) is a red-orange compound that occurs in the normcomponent of the straw-yellow color in urine. Another breakdown product, stercobilin, causes the brown ...

. Increased levels of this chemical are detected in the blood if red blood cells are being destroyed more rapidly than usual. Improperly degraded hemoglobin protein or hemoglobin that has been released from the blood cells too rapidly can clog small blood vessels, especially the delicate blood filtering vessels of the kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

s, causing kidney damage. Iron is removed from heme and salvaged for later use, it is stored as hemosiderin or ferritin

Ferritin is a universal intracellular and extracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. The protein is produced by almost all living organisms, including archaea, bacteria, algae, higher plants, and animals. ...

in tissues and transported in plasma by beta globulins as transferrin

Transferrins are glycoproteins found in vertebrates which bind and consequently mediate the transport of iron (Fe) through blood plasma. They are produced in the liver and contain binding sites for two Iron(III), Fe3+ ions. Human transferrin is ...

s. When the porphyrin ring is broken up, the fragments are normally secreted as a yellow pigment called bilirubin, which is secreted into the intestines as bile. Intestines metabolize bilirubin into urobilinogen. Urobilinogen leaves the body in faeces, in a pigment called stercobilin. Globulin is metabolized into amino acids that are then released into circulation.

Diseases related to hemoglobin

Hemoglobin deficiency can be caused either by a decreased amount of hemoglobin molecules, as inanemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

, or by decreased ability of each molecule to bind oxygen at the same partial pressure of oxygen. Hemoglobinopathies (genetic defects resulting in abnormal structure of the hemoglobin molecule) may cause both. In any case, hemoglobin deficiency decreases blood oxygen-carrying capacity. Hemoglobin deficiency is, in general, strictly distinguished from hypoxemia, defined as decreased partial pressure

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas as if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature. The total pressure of an ideal g ...

of oxygen in blood, although both are causes of hypoxia (insufficient oxygen supply to tissues).

Other common causes of low hemoglobin include loss of blood, nutritional deficiency, bone marrow problems, chemotherapy, kidney failure, or abnormal hemoglobin (such as that of sickle-cell disease).

The ability of each hemoglobin molecule to carry oxygen is normally modified by altered blood pH or CO2, causing an altered oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve. However, it can also be pathologically altered in, e.g., carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning typically occurs from breathing in carbon monoxide (CO) at excessive levels. Symptoms are often described as " flu-like" and commonly include headache, dizziness, weakness, vomiting, chest pain, and confusion. Large ...

.

Decrease of hemoglobin, with or without an absolute decrease of red blood cells, leads to symptoms of anemia. Anemia has many different causes, although iron deficiency and its resultant iron deficiency anemia are the most common causes in the Western world. As absence of iron decreases heme synthesis, red blood cells in iron deficiency anemia are ''hypochromic'' (lacking the red hemoglobin pigment) and ''microcytic'' (smaller than normal). Other anemias are rarer. In hemolysis

Hemolysis or haemolysis (), also known by #Nomenclature, several other names, is the rupturing (lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes) and the release of their contents (cytoplasm) into surrounding fluid (e.g. blood plasma). Hemolysis may ...

(accelerated breakdown of red blood cells), associated jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

is caused by the hemoglobin metabolite bilirubin, and the circulating hemoglobin can cause kidney failure

Kidney failure, also known as renal failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney fa ...

.

Some mutations in the globin chain are associated with the hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle-cell disease and thalassemia

Thalassemias are a group of Genetic disorder, inherited blood disorders that manifest as the production of reduced hemoglobin. Symptoms depend on the type of thalassemia and can vary from none to severe, including death. Often there is mild to ...

. Other mutations, as discussed at the beginning of the article, are benign and are referred to merely as hemoglobin variants.

There is a group of genetic disorders, known as the ''porphyria

Porphyria ( or ) is a group of disorders in which substances called porphyrins build up in the body, adversely affecting the skin or nervous system. The types that affect the nervous system are also known as Porphyria#Acute porphyrias, acute p ...

s'' that are characterized by errors in metabolic pathways of heme synthesis. King George III of the United Kingdom

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Great Britain and Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great ...

was probably the most famous porphyria sufferer.

To a small extent, hemoglobin A slowly combines with glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

at the terminal valine (an alpha aminoacid) of each β chain. The resulting molecule is often referred to as Hb A1c, a glycated hemoglobin. The binding of glucose to amino acids in the hemoglobin takes place spontaneously (without the help of an enzyme) in many proteins, and is not known to serve a useful purpose. However, as the concentration of glucose in the blood increases, the percentage of Hb A that turns into Hb A1c increases. In diabetics whose glucose usually runs high, the percent Hb A1c also runs high. Because of the slow rate of Hb A combination with glucose, the Hb A1c percentage reflects a weighted average of blood glucose levels over the lifetime of red cells, which is approximately 120 days. The levels of glycated hemoglobin are therefore measured in order to monitor the long-term control of the chronic disease of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Poor control of T2DM results in high levels of glycated hemoglobin in the red blood cells. The normal reference range is approximately 4.0–5.9%. Though difficult to obtain, values less than 7% are recommended for people with T2DM. Levels greater than 9% are associated with poor control of the glycated hemoglobin, and levels greater than 12% are associated with very poor control. Diabetics who keep their glycated hemoglobin levels close to 7% have a much better chance of avoiding the complications that may accompany diabetes (than those whose levels are 8% or higher). In addition, increased glycated of hemoglobin increases its affinity for oxygen, therefore preventing its release at the tissue and inducing a level of hypoxia in extreme cases.

Elevated levels of hemoglobin are associated with increased numbers or sizes of red blood cells, called polycythemia

Polycythemia (also known as polycythaemia) is a laboratory finding in which the hematocrit (the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood) and/or hemoglobin concentration are increased in the blood. Polycythemia is sometimes called erythr ...