Kinnereth062 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sea of Galilee (,

The lake is fed partly by underground springs, but its main source is the

The Sea of Galilee is situated in northeast

The Sea of Galilee is situated in northeast

In 1917, the British defeated Ottoman Turkish forces and took control of

In 1917, the British defeated Ottoman Turkish forces and took control of

In 1986 the Ancient Galilee Boat, also known as the Jesus Boat, was discovered on the northwest shore during a drought when water levels receded. It is an ancient fishing boat from the 1st century AD, and although there is no evidence directly linking the boat to Jesus and his disciples, it nevertheless is an example of the kind of boat that Jesus and his disciples, some of whom were fishermen, may have used.

During a routine sonar scan in 2003 (finding published in 2013), archaeologists discovered an enormous conical stone structure. The structure, which has a diameter of around , is made of boulders and stones. The ruins are estimated to be between 2,000 and 12,000 years old and are about underwater. The estimated weight of the monument is over 60,000 tons. Researchers explain that the site resembles early burial sites in Europe and was likely built in the early

In 1986 the Ancient Galilee Boat, also known as the Jesus Boat, was discovered on the northwest shore during a drought when water levels receded. It is an ancient fishing boat from the 1st century AD, and although there is no evidence directly linking the boat to Jesus and his disciples, it nevertheless is an example of the kind of boat that Jesus and his disciples, some of whom were fishermen, may have used.

During a routine sonar scan in 2003 (finding published in 2013), archaeologists discovered an enormous conical stone structure. The structure, which has a diameter of around , is made of boulders and stones. The ruins are estimated to be between 2,000 and 12,000 years old and are about underwater. The estimated weight of the monument is over 60,000 tons. Researchers explain that the site resembles early burial sites in Europe and was likely built in the early

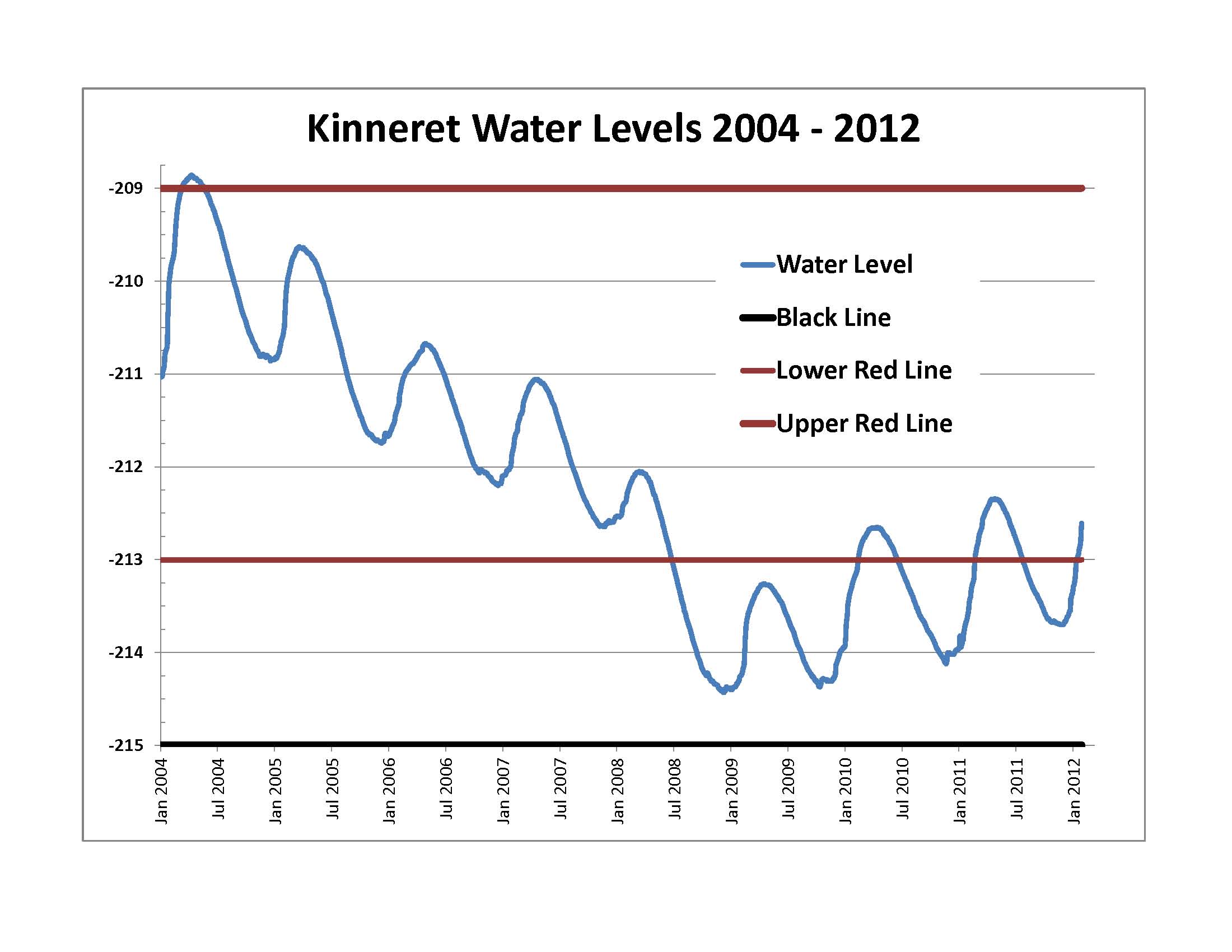

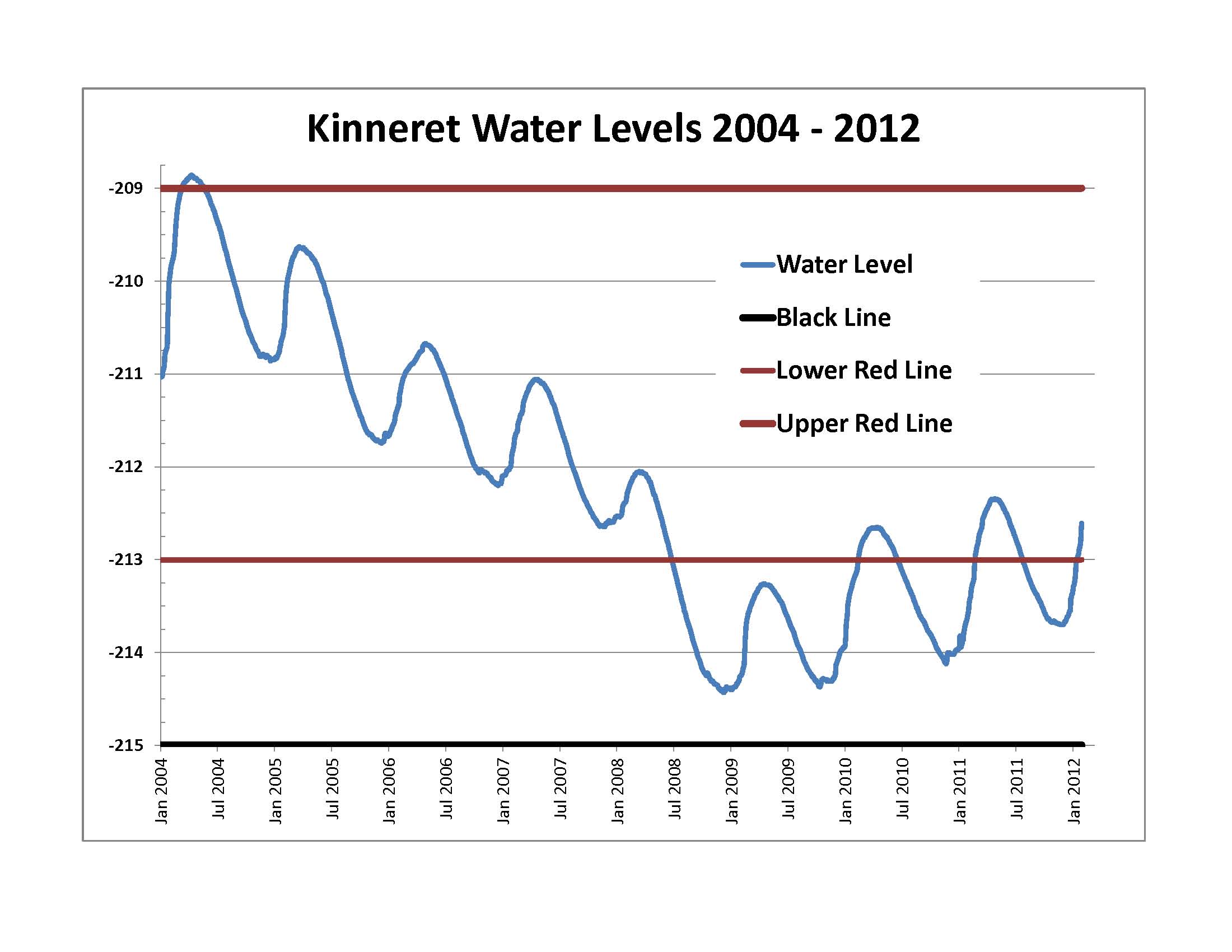

The water level is monitored and regulated. There are three levels at which the alarm is rung:

* The upper red line, below

The water level is monitored and regulated. There are three levels at which the alarm is rung:

* The upper red line, below

Tourism & Nature, 20 February 2019, via Israel Between The Lines, accessed 21 January 2020 Daily monitoring of the Sea of Galilee's water level began in 1969, and the lowest level recorded since then was November 2001, which today constitutes the "black line" of 214.87 meters below sea level (although it is believed that in the first half of the 20th century, the water level had fallen lower than the current black line at times of drought). The Israeli government monitors water levels and publishes the results daily. Increasing water demand in Israel, Lebanon and Jordan, as well as dry winters, have resulted in stress on the lake and a decreasing water line to dangerously low levels at times. The Sea of Galilee is at risk of becoming irreversibly salinized by the salt water springs under the lake, which are held in check by the weight of the freshwater on top of them. After five years of drought up to 2018, the Sea of Galilee was expected to drop near the black line. In February 2018, the city of Tiberias requested a

The

The

Judeo-Aramaic

The Judaeo-Aramaic languages are those varieties of Aramaic and Neo-Aramaic languages used by Jewish communities.

Early use

Aramaic, like Hebrew, is a Northwest Semitic language, and the two share many features. From the 7th century BCE, Ara ...

: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ), also called Lake Tiberias, Genezareth Lake or Kinneret, is a freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include non-salty mi ...

lake

A lake is often a naturally occurring, relatively large and fixed body of water on or near the Earth's surface. It is localized in a basin or interconnected basins surrounded by dry land. Lakes lie completely on land and are separate from ...

in Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth and the second-lowest lake in the world (after the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea (; or ; ), also known by #Names, other names, is a landlocked salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east, the Israeli-occupied West Bank to the west and Israel to the southwest. It lies in the endorheic basin of the Jordan Rift Valle ...

, a salt lake

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per liter). I ...

), with its elevation fluctuating between below sea level (depending on rainfall). It is approximately in circumference, about long, and wide. Its area is at its fullest, and its maximum depth is approximately .Data Summary: Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee)The lake is fed partly by underground springs, but its main source is the

Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and drains to the Dead ...

, which flows through it from north to south with the outflow controlled by the Degania Dam.

Geography

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, between the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights, or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in t ...

and the Galilee

Galilee (; ; ; ) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and the Lower Galilee (, ; , ).

''Galilee'' encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and ...

region, in the Jordan Rift Valley

The Jordan Rift Valley, also Jordan Valley ( ''Bīqʿāt haYardēn'', Al-Ghor or Al-Ghawr), is an elongated endorheic basin located in modern-day Israel, Jordan and the West Bank, Palestine. This geographic region includes the entire length o ...

, formed by the separation of the African and Arabian

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

plates. Consequently, the area is subject to earthquake

An earthquakealso called a quake, tremor, or tembloris the shaking of the Earth's surface resulting from a sudden release of energy in the lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those so weak they ...

s, and in the past, volcanic

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often fo ...

activity. This is evident from the abundant basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

and other igneous

Igneous rock ( ), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

The magma can be derived from partial ...

rocks that define the geology of Galilee.

Names

The lake has been called by different names throughout its history, usually depending on the dominant settlement on its shores. With the changing fate of the towns, the lake's name also changed. The modern Hebrew name ''Kineret'' comes from theHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Hebrew Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

in . This name was also found in the scripts of . '' Hebrew Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

Ugarit

Ugarit (; , ''ủgrt'' /ʾUgarītu/) was an ancient port city in northern Syria about 10 kilometers north of modern Latakia. At its height it ruled an area roughly equivalent to the modern Latakia Governorate. It was discovered by accident in 19 ...

, in the Aqhat Epic. As the name of a city, ''Kinneret'' was listed among the "fenced cities" in . A persistent, though likely erroneous, popular etymology presumes that the name ''Kinneret'' may originate from the Hebrew word ''kinnor

Kinnor ( ''kīnnōr'') is an ancient Israelite musical instrument in the yoke lutes family, the first one to be mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Its exact identification is unclear, but in the modern day it is generally translated as "harp" or ...

'' ("harp" or "lyre"), because of the shape of the lake. The scholarly consensus, however, is that the origin of the name is derived from the important Bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

city of Kinneret, excavated at Tell el-'Oreimeh. The city of Kinneret may have been named after the body of water rather than vice versa, and there is no evidence for the origin of the town's name.

All Old and New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

writers use the term "sea" (Hebrew יָם ''yam'', Greek θάλασσα), with the exception of Luke

Luke may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Luke (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Luke (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Luke the Evangelist, author of the Gospel of Luk ...

, who calls it "the Lake of Gennesaret" (), from the Greek λίμνη Γεννησαρέτ (''limnē Gennēsaret''), the "Grecized form of Chinnereth". The Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewi ...

as well as Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing ''The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Judaea ...

mention the sea by the name "Sea of Ginosar" after the small fertile plain of Ginosar that lies on its western side. Ginosar is yet another name derived from "Kinneret".

The word ''Galilee'' comes from the Hebrew ''Haggalil'' (הַגָלִיל), which literally means "The District", a compressed form of ''Gelil Haggoyim'' "The District of Nations" (Isaiah 8:23). Toward the end of the 1st century CE, the Sea of Galilee became widely known as the ''Sea of Tiberias'' after the city of Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

founded on its western shore in honour of the second Roman emperor, Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

. In the New Testament, the term "sea of Galilee" (, ''thalassan tēs Galilaias'') is used in the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells the story of who the author believes is Israel's messiah (Christ (title), Christ), Jesus, resurrection of Jesus, his res ...

, the Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of Mark is the second of the four canonical Gospels and one of the three synoptic Gospels, synoptic Gospels. It tells of the ministry of Jesus from baptism of Jesus, his baptism by John the Baptist to his death, the Burial of Jesus, ...

, and in the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

as "the sea of Galilee, which is he sea

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

of Tiberias" (θαλάσσης τῆς Γαλιλαίας τῆς Τιβεριάδος, ''thalassēs tēs Galilaias tēs Tiberiados''), the late 1st century CE name. Sea of Tiberias is also the name mentioned in Roman texts and in the Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

, and it was adopted into Arabic as (بحيرة طبريا), "Lake Tiberias". Some writers use the spelling "Gallilee", for example Selah Merrill in a nineteenth century journal article.

From the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

through the Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

period, the lake was known in Arabic as ''Bahr al-Minya'', the "Sea of Minya", after the Umayyad '' qasr'' complex, whose ruins are still visible at Khirbat al-Minya

Khirbet Minya, also known as Qasr al-Minya () or Ayn Minyat Hisham in Arabic and Horvat/Hurvat Minnim in Hebrew, is an Umayyad-built '' qasr'' (palace) in eastern Galilee, Israel, about west of the northern end of Lake Tiberias. It was erected ...

. This is the name used by the medieval Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

scholars Al-Baladhuri

ʾAḥmad ibn Yaḥyā ibn Jābir al-Balādhurī () was a 9th-century West Asian historian. One of the eminent Middle Eastern historians of his age, he spent most of his life in Baghdad and enjoyed great influence at the court of the caliph al ...

, Al-Tabari

Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Jarīr ibn Yazīd al-Ṭabarī (; 839–923 CE / 224–310 AH), commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Sunni Muslim scholar, polymath, historian, exegete, jurist, and theologian from Amol, Tabaristan, present- ...

and Ibn Kathir

Abu al-Fida Isma'il ibn Umar ibn Kathir al-Dimashqi (; ), known simply as Ibn Kathir, was an Arab Islamic Exegesis, exegete, historian and scholar. An expert on (Quranic exegesis), (history) and (Islamic jurisprudence), he is considered a lea ...

.

History

Prehistory

In 1989, remains of ahunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

site were found under the water at the southern end. Remains of mud huts were found in Ohalo

Ohalo II is an archaeological site in the Northern District, Israel, near Kinneret, on the southwest shore of the Sea of Galilee. It is one of the best preserved hunter-gatherer archaeological sites of the Last Glacial Maximum, radiocarbon date ...

. Nahal Ein Gev, located about east of the lake, contains a village from the late Natufian

The Natufian culture ( ) is an archaeological culture of the late Epipalaeolithic Near East in West Asia from 15–11,500 Before Present. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentism, sedentary or semi-sedentary population even befor ...

period. The site is considered one of the first permanent human settlements in the world from a time predating the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunter-gatherer, hunting and gathering to one of a ...

.

Early Iron Age

According to Sugimoto (2015), the Iron Age IB (1150–1000 BCE) cities in the northeastern region of the Sea of Galilee likely reflect the activities of the Kingdom ofGeshur

Geshur () was a territory in the ancient Levant mentioned in the early books of the Hebrew Bible and possibly in several other ancient sources, located in the region of the modern-day Golan Heights. Some scholars suggest it was established as a ...

, mentioned in the Bible. Also, the later Iron Age IIA–B cities here are linked with the southern expansion of the Aram-Damascus

Aram-Damascus ( ) was an Arameans, Aramean polity that existed from the late-12th century BCE until 732 BCE, and was centred around the city of Damascus in the Southern Levant. Alongside various tribal lands, it was bounded in its later years b ...

kingdom. Among these Galilean cities are Tel Dover, Tel ‘En Gev, Tel Hadar, Tel Bethsaida, and Tel Kinrot.

Hellenistic and Roman periods

The Sea of Galilee lies on the ancientVia Maris

Via Maris, or Way of Horus () was an ancient trade route, dating from the early Bronze Age, linking Egypt with the northern empires of Syria, Anatolia and Mesopotamia – along the Mediterranean coast of modern-day Egypt, Israel, Turkey and S ...

, which linked Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

with the northern empires. The Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

, Hasmoneans, and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

founded flourishing towns and settlements on the lake including Hippos

A hippo or hippopotamus is either of two species of large African mammal which live mainly in and near water:

* Hippopotamus

* Pygmy hippopotamus

Hippo or Hippos may also refer to:

Toponymy

* The ancient city of Hippo Regius (modern Annaba, Alg ...

and Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

. Contemporary Roman–Jewish historian Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing ''The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Judaea ...

was so impressed by the area that he wrote, "One may call this place the ambition of Nature"; he also reports a thriving fishing industry at this time, with 230 boats regularly working in the lake. Archaeologists discovered one such boat, nicknamed the Jesus Boat, in 1986.

In the New Testament, much of the ministry of Jesus

The ministry of Jesus, in the canonical gospels, begins with Baptism of Jesus, his baptism near the River Jordan by John the Baptist, and ends in Jerusalem in Christianity, Jerusalem in Judea, following the Last Supper with his Disciple (Chri ...

occurs on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. In those days, there was a continuous ribbon development of settlements and villages around the lake and plenty of trade and ferrying by boat. The Synoptic Gospels

The gospels of Gospel of Matthew, Matthew, Gospel of Mark, Mark, and Gospel of Luke, Luke are referred to as the synoptic Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical ...

of Mark 1

Mark 1 is the first chapter of the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It recounts the proclamation of John the Baptist, the baptism of Jesus Christ, his temptations and the beginning of his ministry in Galilee.

Text ...

:14–20), Matthew 4

Matthew 4 is the fourth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament of Christianity, Christian Bible.Halley, Henry H. (1962), ''Halley's Bible Handbook'': an Abbreviated Bible Commentary. 23rd edition. Zondervan Publishing House.Holman I ...

:18–22), and Luke 5:1–11) describe how Jesus recruited four of his apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary. The word is derived from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", itself derived from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to se ...

from the shores of the Kinneret: the fishermen Simon and his brother Andrew

Andrew is the English form of the given name, common in many countries. The word is derived from the , ''Andreas'', itself related to ''aner/andros'', "man" (as opposed to "woman"), thus meaning "manly" and, as consequence, "brave", "strong", "c ...

and the brothers John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and James

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

. One of Jesus' famous teaching episodes, the Sermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount ( anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings spoken by Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is th ...

, is supposed to have been given on a hill overlooking the Kinneret. Many of his miracles are also said to have occurred here including his walking on water, calming the storm

Calming the storm is one of the miracles of Jesus in the Gospels, reported in Matthewbr>8:23–27 Markbr>4:35–41 and Lukebr>8:22–25(the Synoptic Gospels). This episode is distinct from Jesus' walk on water, which also involves a boat on ...

, the disciples and the miraculous catch of fish

The miraculous catch of fish, or more traditionally the miraculous draught of fish(es), is either of two events commonly (but not universally) considered to be miracles in the canonical gospels. The miracles are reported as taking place years ap ...

, and his feeding five thousand people (in Tabgha

Tabgha (, ''al-Tabigha''; , ''Ein Sheva'' which means "spring of seven") is an area situated on the north-western shore of the Sea of Galilee in Israel and a depopulated Palestinian village. It is traditionally accepted as the place of the feedi ...

). In John's Gospel the sea provides the setting for Jesus' third post-resurrection appearance to his disciples (John 21

John 21 is the twenty-first and final chapter of the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It contains an account of a post-crucifixion appearance in Galilee, which the text describes as the third time Jesus had appeared t ...

).

In 135 CE, Bar Kokhba's revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 AD) was a major uprising by the Jews of Judaea against the Roman Empire, marking the final and most devastating of the Jewish–Roman wars. Led by Simon bar Kokhba, the rebels succeeded in establishing an indep ...

was put down which was part of the Jewish–Roman wars

The Jewish–Roman wars were a series of large-scale revolts by the Jews of Judaea against the Roman Empire between 66 and 135 CE. The conflict was driven by Jewish aspirations to restore the political independence lost when Rome conquer ...

. The Romans responded by banning all Jews from Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. The center of Jewish culture and learning shifted to the region of Galilee and the Kinneret, particularly Tiberias. It was in this region that the Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

was compiled.

Middle Ages

The Sea of Galilee's importance declined when theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

lost control, and the area came under the control of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

and subsequent Islamic empires. The palace of Minya was built by the lake during the reign of al-Walid I

Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (; – 23 February 715), commonly known as al-Walid I (), was the sixth Umayyad caliph, ruling from October 705 until his death in 715. He was the eldest son of his predecessor, Caliph Abd al-Malik (). As ...

(705–715 CE). Apart from Tiberias, the major towns and cities in the area were gradually abandoned. In 1187, Sultan Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

defeated the armies of the Crusader

Crusader or Crusaders may refer to:

Military

* Crusader, a participant in one of the Crusades

* Convair NB-36H Crusader, an experimental nuclear-powered bomber

* Crusader tank, a British cruiser tank of World War II

* Crusaders (guerrilla), a C ...

Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, also known as the Crusader Kingdom, was one of the Crusader states established in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade. It lasted for almost two hundred years, from the accession of Godfrey of Bouillon in 1 ...

at the Battle of Hattin

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of ...

, largely because he was able to cut the Crusaders off from the valuable fresh water of the Sea of Galilee.

The lake had little importance within the early Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Tiberias did see a significant revival of its Jewish community in the 16th century but had gradually declined until the city was destroyed in 1660. In the early 18th century, Tiberias was rebuilt by Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Dhaher el-OmarDAAHL Site Rec ...

, becoming the center of his rule over Galilee, and seeing also a revival of its Jewish community.

Early 20th century

In 1908, Jewish pioneers established theKinneret Farm

Kinneret Farm () or Kinneret Courtyard () was an experimental training farm established in 1908 in Ottoman Palestine by the Palestine Bureau of the Zionist Organization (ZO) led by Arthur Ruppin, at the same time as, and next to Moshavat Kinnere ...

at the same time as and next to Moshavat Kinneret in the immediate vicinity of the lake. The farm trained Jewish immigrants in modern farming. One group of youth from the training farm established Kvutza

A kvutza, kvutzah, kevutza or kevutzah ( "group") is a form of cooperative settlement that was founded in the Second Aliyah and developed in the Third Aliyah, its principles are based on the existence of a cooperative, communal, small and intima ...

t Degania in 1909–1910, popularly considered as the first kibbutz

A kibbutz ( / , ; : kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1910, was Degania Alef, Degania. Today, farming has been partly supplanted by other economi ...

, another group founded Kvutzat Kinneret

Kvutzat Kinneret (), also known as Kibbutz Kinneret, is a kibbutz in northern Israel. The settlement group ('' kvutza'') was established in 1913, and moved from the Kinneret training farm to the permanent location in 1929. Located to the southwest ...

in 1913, and yet another the first proper kibbutz, Ein Harod

Ein Harod () was a kibbutz in northern Israel near Mount Gilboa. Founded in 1921, it became the center of Mandatory Israel's kibbutz movement, hosting the headquarters of the largest kibbutz organisation, HaKibbutz HaMeuhad.

In 1923 part of the ...

, in 1921, the same year when the first moshav

A moshav (, plural ', "settlement, village") is a type of Israeli village or town or Jewish settlement, in particular a type of cooperative agricultural community of individual farms pioneered by the Labour Zionists between 1904 and 1 ...

, Nahalal

Nahalal () is a moshav in Northern District (Israel), northern Israel. Covering , it falls under the jurisdiction of the Jezreel Valley Regional Council. In it had a population of .

Nahalal is best known for its general layout, as designed by ...

, was established by a group trained at the farm. The Jewish settlements around Kinneret Farm are considered the cradle of the kibbutz culture of early Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

; Kvutzat Kinneret is the birthplace of Naomi Shemer

Naomi Shemer (; July 13, 1930 – June 26, 2004) was a leading Israeli musician and songwriter, hailed as the "first lady of Israeli song and poetry." Her song " Yerushalayim Shel Zahav" ("Jerusalem of Gold"), written in 1967, became an unoffic ...

, buried at the Kinneret Cemetery next to Rachel

Rachel () was a Bible, Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph (Genesis), Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban (Bible), Laban. Her older siste ...

—two prominent national poets. In 1917, the British defeated Ottoman Turkish forces and took control of

In 1917, the British defeated Ottoman Turkish forces and took control of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, while France took control of Syria. In the carve-up of the Ottoman territories between Britain and France, it was agreed that Britain would retain control of Palestine while France would control Syria. This required the allies to fix the border between the Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

and the French Mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (; , also referred to as the Levant States; 1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate founded in the aftermath of the First World War and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, concerning the territories ...

. The boundary was defined in broad terms by the Franco-British Boundary Agreement of December 1920, which drew it across the middle of the lake.Franco-British Convention on Certain Points Connected with the Mandates for Syria and the Lebanon, Palestine and Mesopotamia, signed 23 December 1920. Text available in ''American Journal of International Law'', Vol. 16, No. 3, 1922, 122–126. However, the commission established by the 1920 treaty redrew the boundary. The Zionist movement pressured the French and British to assign as many water sources as possible to Mandatory Palestine during the demarcating negotiations. The High Commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel (6 November 1870 – 5 February 1963) was a British Liberal politician who was the party leader from 1931 to 1935.

He was the first nominally-practising Jew to serve as a Cabinet minister and to becom ...

, had sought full control of the Sea of Galilee. The negotiations led to the inclusion into the Palestine territory of the whole Sea of Galilee, both sides of the River Jordan

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic basin, endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and d ...

, Lake Hula

The Hula Valley () is a valley and fertile agriculture, agricultural region in northern Israel with abundant fresh water that used to be Lake Hula before it was drained. It is a major stopover for birds migrating along the Great Rift Valley be ...

, Dan spring, and part of the Yarmouk. The final border approved in 1923 followed a 10-meter wide strip along the lake's northeastern shore, cutting the Mandatory Syria (State of Damascus

The State of Damascus (; ') was one of the six states established by the French General Henri Gouraud in the French Mandate of Syria which followed the San Remo conference of 1920 and the defeat of King Faisal's short-lived monarchy in Syri ...

) off from the lake.

The British and French Agreement provided that existing rights over the use of the waters of the River Jordan by the inhabitants of Syria would be maintained; the government of Syria would have the right to erect a new pier at Semakh on Lake Tiberias or jointly use the existing pier; persons or goods passing between the landing-stage on the Lake of Tiberias and Semakh would not be subject to customs regulations, and the Syrian government would have access to the said landing-stage; the inhabitants of Syria and Lebanon would have the same fishing and navigation rights on Lakes Huleh, Tiberias and River Jordan, while the government of Palestine would be responsible for policing of lakes.

State of Israel

On 15 May 1948, Syria invaded the newborn state of Israel, capturing territory along the Sea of Galilee. Under the 1949armistice agreement

An armistice is a Treaty, formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived f ...

between Israel and Syria, Syria occupied the northeast shoreline of the Sea of Galilee. The agreement stated that the armistice line was "not to be interpreted as having any relation whatsoever to ultimate territorial arrangements." Syria remained in possession of the lake's northeast shoreline until the 1967 Arab-Israeli war.

In the 1950s, Israel formulated a plan to link the Kinneret with the rest of the country's water infrastructure via the National Water Carrier

National Water Carrier of Israel

The National Water Carrier of Israel (, ''HaMovil HaArtzi'') is the largest water project in Israel, completed in 1964. Its main purpose is to transfer water from the Sea of Galilee in the north of the country ...

, in order to supply the water demand of the growing country. The carrier was completed in 1964. The Israeli plan, which the Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

opposed while endorsing its own plan to divert the headwaters of the Jordan River, sparked political and sometimes even armed confrontations over the Jordan basin.

Geology

The lake lies in the center of the Jordan Valley, in the northern part of the Syrian-African rift. Several directions of tectonic movements characterize the region, mirroring the patterns typical of the entire Syrian-African rift: north–south movements, which started about 20 million years ago; stretching movements in the east–west direction, which began later, at the beginning of thePleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

(about 1.8 million years ago), and caused the subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

of the lake area.

As a result of horizontal shifts in the north–south direction and subsidence of the area, a lake was formed, with an asymmetrical bottom—steeper in the east and a gentler in the west. In the southern part an underwater cliff is present, covered by the lake's sediments. The cliff is distinct in the western part and less so in the east.

The Sea of Galilee in its current form was preceded by Lake Lisan, which extended from the northern Sea of Galilee to Hatzeva

Hatzeva () is a moshav in southern Israel. Located in the Arava valley, 12 km north of Ein Yahav, it falls under the jurisdiction of Central Arava Regional Council. In it had a population of .

History Antiquity

The nearby holds remain ...

in the south, more than from the present southernmost point of the lake. Lake Lisan was preceded by Lake Ovadia, a much smaller fresh water lake. Lake Kinneret was formed in its current form less than 20,000 years ago, as a result of tectonic subsidence and the shrinking up of Lake Lisan.

Archaeology

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

.

In February 2018, archaeologists discovered seven intact mosaics with Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

inscriptions. One inscription, at five meters one of the longest found to date in western Galilee, gives the names of donors and the names and positions of church officials, including Irenaeus, bishop of Tyre in 445. Another mosaic mentions a woman as a donor to the church's construction. This inscription is the first in the region to mention a female donor.

Water level

The water level is monitored and regulated. There are three levels at which the alarm is rung:

* The upper red line, below

The water level is monitored and regulated. There are three levels at which the alarm is rung:

* The upper red line, below sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

(BSL), where facilities on the shore start being flooded.

* The lower red line, BSL, where pumping should stop.

* The black (low-level) line, BSL, where irreversible damage occurs.The Rise and Fall of the Sea of GalileeTourism & Nature, 20 February 2019, via Israel Between The Lines, accessed 21 January 2020 Daily monitoring of the Sea of Galilee's water level began in 1969, and the lowest level recorded since then was November 2001, which today constitutes the "black line" of 214.87 meters below sea level (although it is believed that in the first half of the 20th century, the water level had fallen lower than the current black line at times of drought). The Israeli government monitors water levels and publishes the results daily. Increasing water demand in Israel, Lebanon and Jordan, as well as dry winters, have resulted in stress on the lake and a decreasing water line to dangerously low levels at times. The Sea of Galilee is at risk of becoming irreversibly salinized by the salt water springs under the lake, which are held in check by the weight of the freshwater on top of them. After five years of drought up to 2018, the Sea of Galilee was expected to drop near the black line. In February 2018, the city of Tiberias requested a

desalination

Desalination is a process that removes mineral components from saline water. More generally, desalination is the removal of salts and minerals from a substance. One example is Soil salinity control, soil desalination. This is important for agric ...

plant to treat the water coming from the Sea of Galilee and demanded a new water source for the city. March 2018 was the lowest point in water income to the lake since 1927. In September 2018 the Israeli energy and water office announced a project to pour desalinated water from the Mediterranean Sea into the Sea of Galilee using a tunnel. The tunnel is expected to be the largest of its kind in Israel and will transfer half of the Mediterranean desalted water and will move 300 to 500 million cubic meters of water per year. The plan is said to cost five billion shekels.

Since the beginning of the 2018–19 rainy season, the Sea of Galilee has risen considerably. From being near the ecologically dangerous black line of −214.4 m, the level has risen by April 2020 to just below the upper red line, a result of strong rains and a radical decrease in pumping. During the entire 2018–19 rainy season the water level rose by a historical record of , while the 2019–20 winter brought a rise. The Water Authority dug a new canal in order to let of water flow from the lake directly into the Jordan River, bypassing the existing dams system for technical and financial reasons.

Water use

The

The National Water Carrier of Israel

image:National Water Carrier of Israel -en.svg, National Water Carrier of Israel

The National Water Carrier of Israel (, ''HaMovil HaArtzi'') is the largest water project in Israel, completed in 1964. Its main purpose is to transfer water from ...

, completed in 1964, transports water from the lake to the population centers of Israel, and in the past supplied most of the country's drinking water. In 2016 the lake supplied approximately 10% of Israel's drinking water needs.

In 1964, Syria attempted construction of a Headwater Diversion Plan

The Headwater Diversion Plan was an Arab League plan to divert two of the three sources of the Jordan River, and prevent them from flowing into the Sea of Galilee, in order to thwart Israel's plans to use the water of the Hasbani and Bania ...

that would have blocked the flow of water into the Sea of Galilee, sharply reducing the water flow into the lake. This project and Israel's attempt to block these efforts in 1965 were factors which played into regional tensions culminating in the 1967 Six-Day War. During the war, Israel captured the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights, or simply the Golan, is a basaltic plateau at the southwest corner of Syria. It is bordered by the Yarmouk River in the south, the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley in the west, the Anti-Lebanon mountains with Mount Hermon in t ...

, which contain some of the sources of water for the Sea of Galilee.

Up until the mid-2010s, about of water was pumped through the National Water Carrier each year. Under the terms of the Israel–Jordan peace treaty

The Israel–Jordan peace treaty (formally the "Treaty of Peace Between the State of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan"),; Hebrew transliteration, transliterated: ''Heskem Ha-Shalom beyn Yisra'el Le-Yarden''; ; Arabic transliteration: ' ...

, Israel also supplies of water annually from the lake to Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

. In recent years the Israeli government has made extensive investments in water conservation

Water conservation aims to sustainably manage the natural resource of fresh water, protect the hydrosphere, and meet current and future human demand. Water conservation makes it possible to avoid water scarcity. It covers all the policies, strateg ...

, reclamation and desalination

Desalination is a process that removes mineral components from saline water. More generally, desalination is the removal of salts and minerals from a substance. One example is Soil salinity control, soil desalination. This is important for agric ...

infrastructure in the country. This has allowed it to significantly reduce the amount of water pumped from the lake annually in an effort to restore and improve its ecological environment, as well as respond to some of the most extreme drought conditions in hundreds of years affecting the lake's intake basin since 1998. Therefore, it was expected that in 2016 only about of water would be drawn from the lake for Israeli domestic consumption, a small fraction of the amount typically drawn from the lake over the previous decades.

Tourism

Tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure, and the Commerce, commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel. World Tourism Organization, UN Tourism defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as ...

around the Sea of Galilee is an important economic segment. Historical and religious sites in the region draw both local and foreign tourists. The Sea of Galilee is an attraction for Christian pilgrims

Christianity has a strong tradition of pilgrimages, both to sites relevant to the New Testament narrative (especially in the Holy Land) and to sites associated with later saints or miracles.

History

Christian pilgrimages were first made to sit ...

who visit Israel to see the places where Jesus performed miracles according to the New Testament. Alonzo Ketcham Parker, a 19th-century American traveler, called visiting the Sea of Galilee "a 'fifth gospel' which one read devoutly, his heart overflowing with quiet joy".

In April 2011, Israel unveiled a hiking trail in Galilee for Christian pilgrims, called the " Jesus Trail". It includes a network of footpaths, roads and bicycle paths linking sites central to the lives of Jesus and his disciples. It ends at Capernaum

Capernaum ( ; ; ) was a fishing village established during the time of the Hasmoneans, located on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. It had a population of about 1,500 in the 1st century AD. Archaeological excavations have revealed tw ...

on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, where Jesus expounded his teachings. Another key attraction is the site where the Sea of Galilee's water flows into the Jordan River, to which thousands of pilgrims from all over the world come to be baptized every year.

Israel's most well-known open water swim race, the Kinneret Crossing, is held every year in September, drawing thousands of open water swimmers to participate in competitive and noncompetitive events. Tourists also partake in the building of rafts on ''Lavnun Beach'', called Rafsodia. Here many different age groups work together to build a raft with their bare hands and then sail that raft across the sea. Other economic activities include fishing in the lake and agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, particularly banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large treelike herbaceous flowering plants in the genus '' Musa''. In some countries, cooking bananas are called plantains, distinguishing the ...

s, dates, mangoes, grapes and olives in the fertile belt of land surrounding it.

The Turkish Aviators Monument, erected during the Ottoman era, stands near Kibbutz Ha'on on the lakeshore, commemorating the Turkish pilots whose monoplanes crashed en route to Jerusalem.

Ecology

The warm waters of the Sea of Galilee support various flora and fauna, which have supported a significant commercial fishery for more than two millennia. Local flora include various reeds along most of the shoreline as well asphytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

. Fauna include zooplankton

Zooplankton are the heterotrophic component of the planktonic community (the " zoo-" prefix comes from ), having to consume other organisms to thrive. Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents. Consequent ...

, benthos

Benthos (), also known as benthon, is the community of organisms that live on, in, or near the bottom of a sea, river, lake, or stream, also known as the benthic zone.Mirogrex terraesanctae''. The Fishing and Agricultural Division of the Ministry of Water and Agriculture of Israel lists 10 families of fish living in the lake, with a total of 27 species – 19 native and 8

World Lakes Database entry for Sea of Galilee

Kinneret Data Center

// Kinneret Limnological Laboratory

Sea of Galilee

– official government page (in Hebrew)

Sea of Galilee water level

– official government page (in Hebrew)

Database: Water levels of Sea of Galilee since 1966

(in Hebrew)

Updated elevation of the Kinneret's level

(in Hebrew) – elevation (meters below sea level) is shown on the line following the date line {{DEFAULTSORT:Galilee, Sea Of Lakes of Israel

introduced species

An introduced species, alien species, exotic species, adventive species, immigrant species, foreign species, non-indigenous species, or non-native species is a species living outside its native distributional range, but which has arrived ther ...

. Local fishermen talk of four types of fish: "مشط musht" (tilapia

Tilapia ( ) is the common name for nearly a hundred species of cichlid fish from the coelotilapine, coptodonine, heterotilapine, oreochromine, pelmatolapiine, and tilapiine tribes (formerly all were "Tilapiini"), with the economically mos ...

); sardin (the Kinneret bleak, '' Mirogrex terraesanctae''); "بني biny" or Jordan barbel, '' Luciobarbus longiceps'' ( barb-like); and North African sharptooth catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order (biology), order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Catfish are common name, named for their prominent barbel (anatomy), barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, though not ...

(''Clarias gariepinus

''Clarias gariepinus'' or African sharptooth catfish is a species of catfish of the family Clariidae, the airbreathing catfishes.

Distribution

They are found throughout Africa and the Middle East, and live in freshwater lakes, rivers, and swa ...

''). The tilapia species include the Galilean tilapia ('' Sarotherodon galilaeus''), the blue tilapia (''Oreochromis aureus

The blue tilapia (''Oreochromis aureus'') is a species of tilapia, a fish in the family Cichlidae. Native to Northern and Western Africa, and the Middle East, through introductions it is now also established elsewhere, including parts of the ...

''), and the redbelly tilapia ('' Tilapia zillii''). Fish caught commercially include ''Tristramella simonis

''Tristramella simonis'', the short jaw tristramella, is a Vulnerable species, vulnerable species of cichlid fish from the Jordan River system, including Lake Tiberias (Kinneret), in Israel and Syria, with Introduced species, introduced populatio ...

'' and the Galilean tilapia, locally called "St. Peter's fish". In 2005, of tilapia were caught by local fishermen. This dropped to in 2009 because of overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing Fish stocks, fish stock), resu ...

. A fish species that is unique to the lake, '' Tristramella sacra'', used to spawn

Spawn or spawning may refer to:

* Spawning, the eggs and sperm of aquatic animals

Arts, entertainment and media

* Spawn (character), a fictional character in the comic series of the same name and in the associated franchise

** ''Spawn: Armageddon' ...

in the marsh and has not been seen since the 1990s droughts. Conservationists fear this species may have become extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

.

Low water levels in drought years have stressed the lake's ecology. This may have been aggravated by over-extraction of water for either the National Water Carrier to supply other parts of Israel or, since 1994, for the supply of water to Jordan. Droughts of the early and mid-1990s dried out the marshy northern margin of the lake. It is hoped that drastic reductions in the amount of water pumped through the National Water Carrier will help restore the lake's ecology over the span of several years.

The lake, with its immediate surrounds, has been recognised as an Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding i ...

because it supports populations of black francolin

The black francolin (''Francolinus francolinus'') is a gamebird in the pheasant family Phasianidae of the order Galliformes. It was formerly known as the black partridge. It is the state bird of Haryana state, India (locally known as ''kaala teet ...

s and non-breeding griffon vulture

The Eurasian griffon vulture (''Gyps fulvus'') is a large Old World vulture in the bird of prey family Accipitridae. It is also known as the griffon vulture, although this term is sometimes used for the genus as a whole. It is not to be confuse ...

s as well as many wintering waterbirds, including marbled teal

The marbled duck or marbled teal (''Marmaronetta angustirostris'') is a medium-sized species of duck from southern Europe, northern Africa, and western and central Asia. The scientific name, ''Marmaronetta angustirostris'', comes from the Greek ' ...

s, great crested grebe

The great crested grebe (''Podiceps cristatus'') is a member of the grebe family of water birds. The bird is characterised by its distinctive appearance, featuring striking black, orange-brown, and white plumage, and elaborate courtship displa ...

s, grey heron

The grey heron (''Ardea cinerea'') is a long-legged wading bird of the heron family, Ardeidae, native throughout temperate Europe and Asia, and also parts of Africa. It is resident in much of its range, but some populations from the more norther ...

s, great white egret

The great egret (''Ardea alba''), also known as the common egret, large egret, great white egret, or great white heron, is a large, widely distributed egret. The four subspecies are found in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and southern Europe. R ...

s, great cormorant

The great cormorant (''Phalacrocorax carbo''), also known as just cormorant in Britain, as black shag or kawau in New Zealand, formerly also known as the great black cormorant across the Northern Hemisphere, the black cormorant in Australia, and ...

s and black-headed gull

The black-headed gull (''Chroicocephalus ridibundus'') is a small gull that breeds in much of the Palearctic in Europe and Asia, and also locally in smaller numbers in coastal eastern Canada. Most of the population is migratory and winters fu ...

s.

See also

*Miracles of Jesus

The miracles of Jesus are the many miraculous deeds attributed to Jesus in Christian texts, with the majority of these miracles being faith healings, exorcisms, resurrections, and control over nature.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus is said to ...

* ''The Storm on the Sea of Galilee

''Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee'' is a 1633 oil-on-canvas painting by the Dutch Golden Age painter Rembrandt van Rijn. It is classified as a history painting and ranks among the largest and earliest of Rembrandt's works. Purchased b ...

'' (1633 Rembrandt painting)

References

Further reading

* *External links

World Lakes Database entry for Sea of Galilee

Kinneret Data Center

// Kinneret Limnological Laboratory

Sea of Galilee

– official government page (in Hebrew)

Sea of Galilee water level

– official government page (in Hebrew)

Database: Water levels of Sea of Galilee since 1966

(in Hebrew)

Updated elevation of the Kinneret's level

(in Hebrew) – elevation (meters below sea level) is shown on the line following the date line {{DEFAULTSORT:Galilee, Sea Of Lakes of Israel

Sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

Sea

A sea is a large body of salt water. There are particular seas and the sea. The sea commonly refers to the ocean, the interconnected body of seawaters that spans most of Earth. Particular seas are either marginal seas, second-order section ...

Tourist attractions in Israel

Catholic pilgrimage sites

Sacred lakes

Shrunken lakes

Jordan River basin

Important Bird Areas of Israel

Lowest points of countries