Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a

After losing their remaining South African lands in 1840, Mzilikazi and his tribe permanently settled in the southwest of present-day Zimbabwe in what became known as Matabeleland, establishing

After losing their remaining South African lands in 1840, Mzilikazi and his tribe permanently settled in the southwest of present-day Zimbabwe in what became known as Matabeleland, establishing

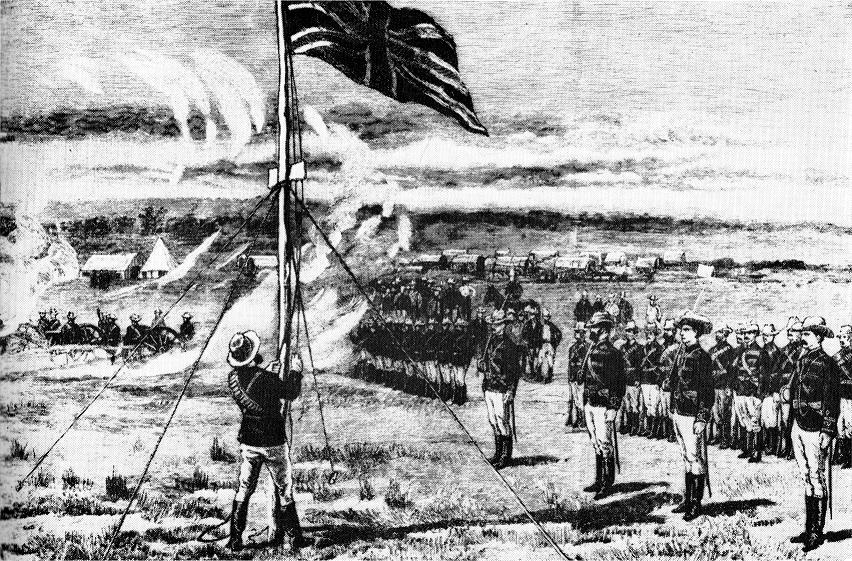

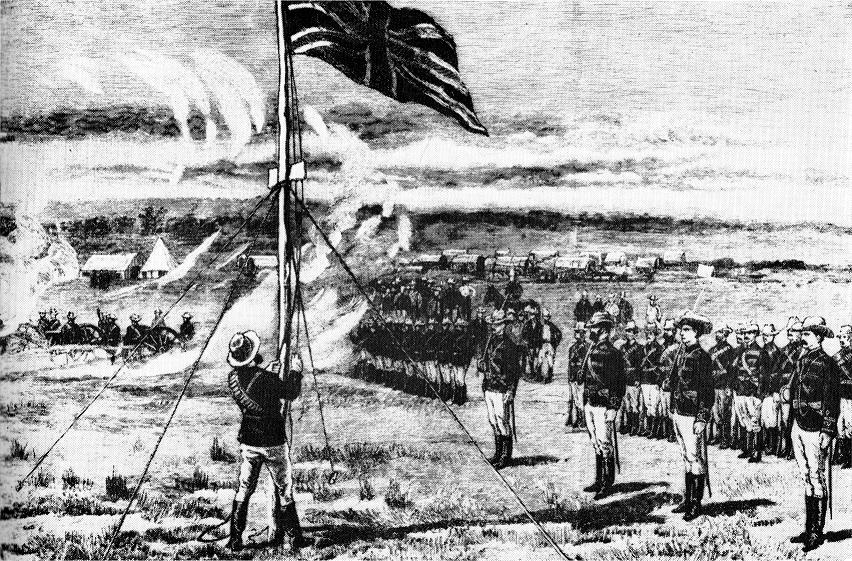

In the 1880s, European colonists arrived with

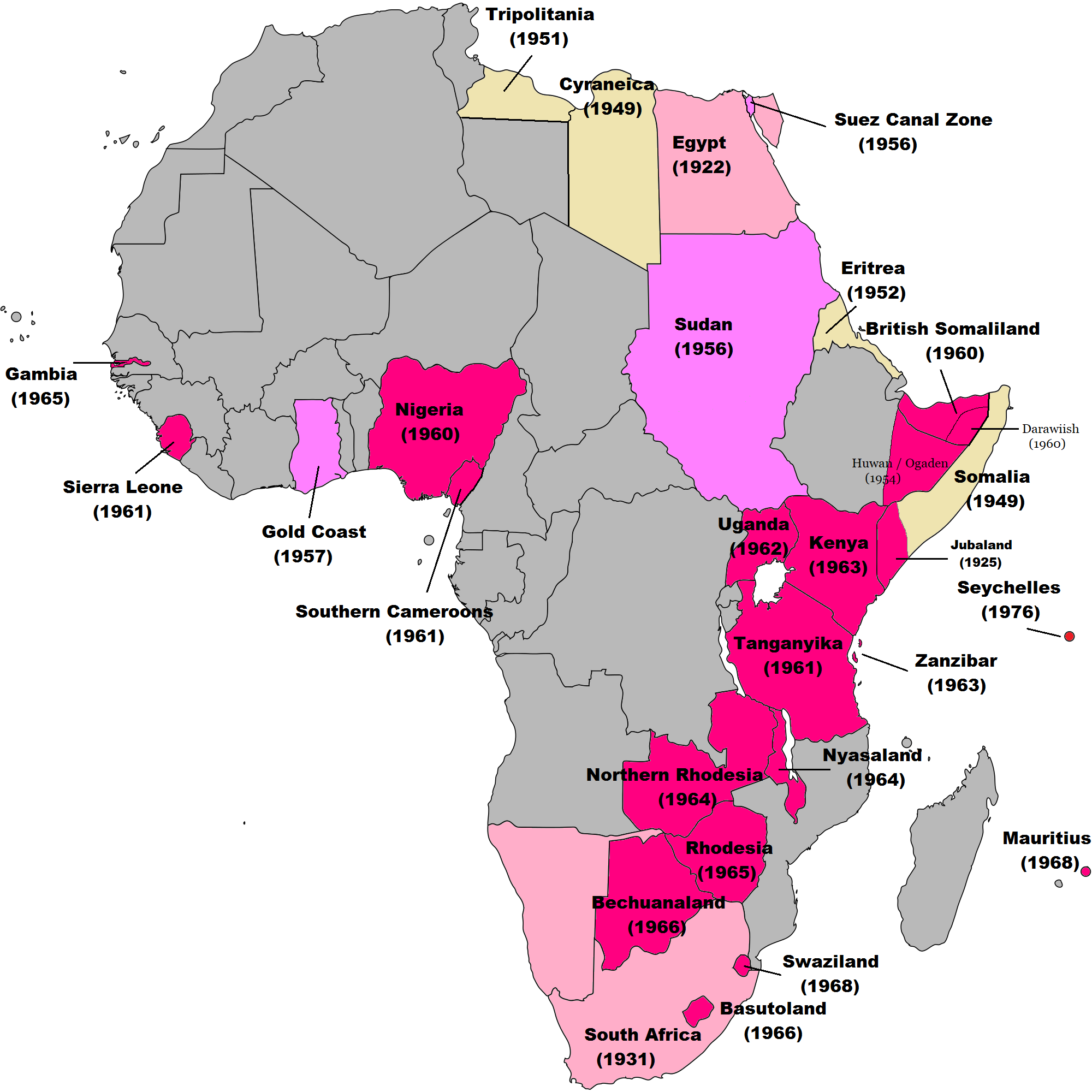

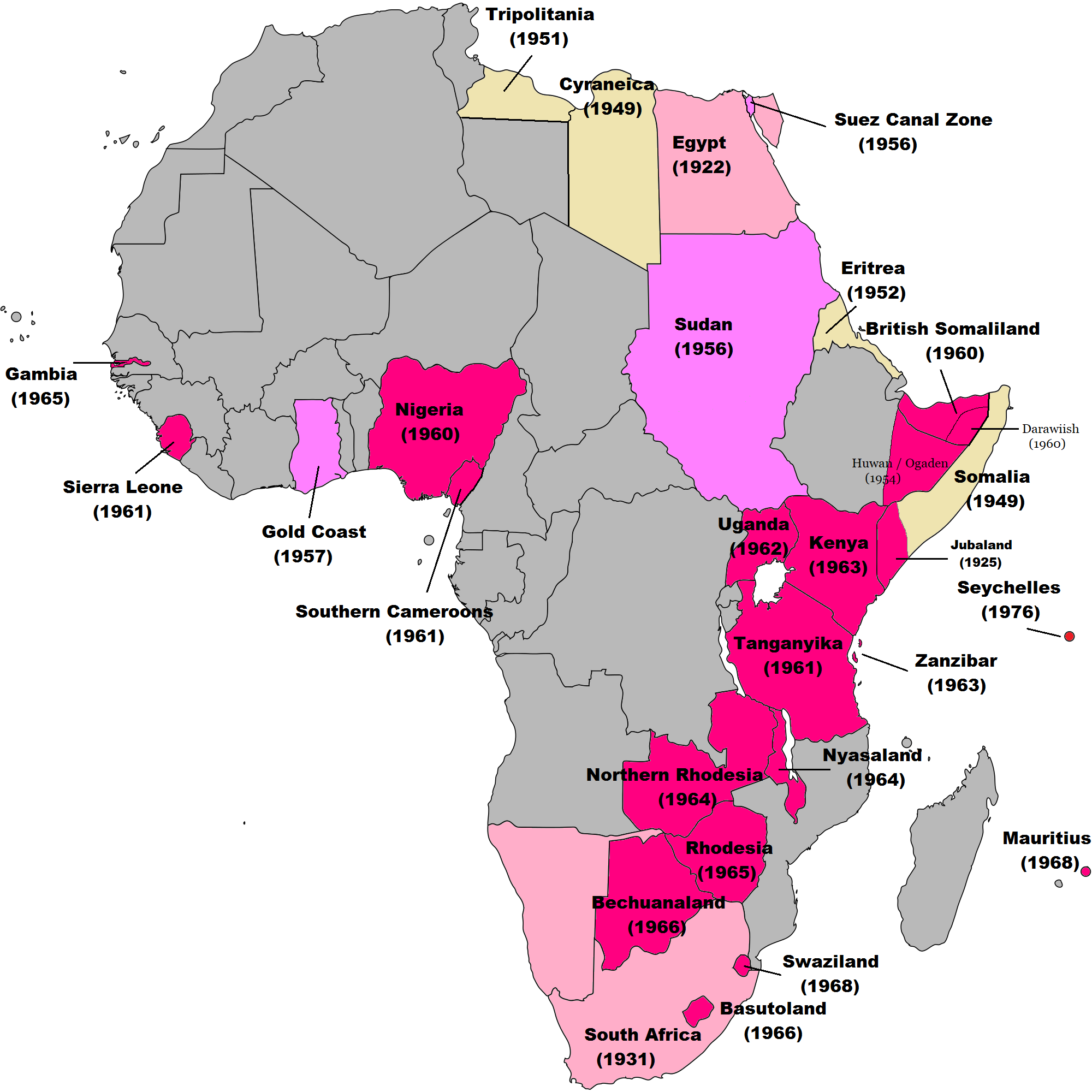

In the 1880s, European colonists arrived with  In 1895, the BSAC adopted the name "Rhodesia" for the territory, in honour of Rhodes. In 1898 "Southern Rhodesia" became the official name for the region south of the Zambezi, which later adopted the name "Zimbabwe". The region to the north, administered separately, was later termed

In 1895, the BSAC adopted the name "Rhodesia" for the territory, in honour of Rhodes. In 1898 "Southern Rhodesia" became the official name for the region south of the Zambezi, which later adopted the name "Zimbabwe". The region to the north, administered separately, was later termed  Following Zambian independence (effective from October 1964),

Following Zambian independence (effective from October 1964),

Re-living the Second Chimurenga: memories from the liberation struggle in Zimbabwe

', Preben (INT) Kaarsholm. p. 242; . With Lord Carrington, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs of the United Kingdom, in the chair, these discussions were mounted from 10 September to 15 December in 1979, producing a total of 47

On 29 March 2008, Zimbabwe held a

On 29 March 2008, Zimbabwe held a  In late 2008, problems in Zimbabwe reached crisis proportions in the areas of living standards, public health (with a major cholera outbreak in December) and various basic affairs. During this period, NGOs took over from government as a primary provider of food during this period of food insecurity in Zimbabwe. A 2011 survey by

In late 2008, problems in Zimbabwe reached crisis proportions in the areas of living standards, public health (with a major cholera outbreak in December) and various basic affairs. During this period, NGOs took over from government as a primary provider of food during this period of food insecurity in Zimbabwe. A 2011 survey by

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in southern Africa, lying between latitudes 15° and 23°S, and longitudes 25° and 34°E. It is bordered by

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in southern Africa, lying between latitudes 15° and 23°S, and longitudes 25° and 34°E. It is bordered by

Zimbabwe contains seven terrestrial ecoregions: Kalahari acacia–baikiaea woodlands, Southern Africa

Zimbabwe contains seven terrestrial ecoregions: Kalahari acacia–baikiaea woodlands, Southern Africa

Zimbabwe is a republic with a

Zimbabwe is a republic with a

''Independent Online Zimbabwe'', 12 March 2005. Moyo participated in the elections despite the allegations and won a seat as an independent member of Parliament. In 2005, the MDC split into two factions: the Movement for Democratic Change – Mutambara ( MDC-M), led by

In 2005, the MDC split into two factions: the Movement for Democratic Change – Mutambara ( MDC-M), led by

The Zimbabwe Defence Forces were set up by unifying three insurrectionist forces – the

The Zimbabwe Defence Forces were set up by unifying three insurrectionist forces – the

There are widespread reports of systematic and escalating violations of human rights in Zimbabwe under the Mugabe administration and the dominant ZANU–PF party. According to human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and

There are widespread reports of systematic and escalating violations of human rights in Zimbabwe under the Mugabe administration and the dominant ZANU–PF party. According to human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and

''Press Reference'', 2006. Newspapers critical of the government, such as the '' Daily News'', closed after bombs exploded at their offices and the government refused to renew their licence.

''

Zimbabwe has a

Zimbabwe has a

The main foreign exports of Zimbabwe are minerals, gold, and agriculture. Zimbabwe is crossed by two trans-African automobile routes: the Cairo-Cape Town Highway and the Beira-Lobito Highway. Zimbabwe is the largest trading partner of South Africa on the continent. Taxes and tariffs are high for private enterprises, while state enterprises are strongly subsidised. State regulation is costly to companies; starting or closing a business is slow and expensive. Tourism also plays a key role in the economy but has been failing in recent years. The Zimbabwe Conservation Task Force released a report in June 2007, estimating that 60% of Zimbabwe's wildlife had died since 2000 as a result of poaching and deforestation. The report warns that the loss of life combined with widespread deforestation is potentially disastrous for the tourism industry. The

The main foreign exports of Zimbabwe are minerals, gold, and agriculture. Zimbabwe is crossed by two trans-African automobile routes: the Cairo-Cape Town Highway and the Beira-Lobito Highway. Zimbabwe is the largest trading partner of South Africa on the continent. Taxes and tariffs are high for private enterprises, while state enterprises are strongly subsidised. State regulation is costly to companies; starting or closing a business is slow and expensive. Tourism also plays a key role in the economy but has been failing in recent years. The Zimbabwe Conservation Task Force released a report in June 2007, estimating that 60% of Zimbabwe's wildlife had died since 2000 as a result of poaching and deforestation. The report warns that the loss of life combined with widespread deforestation is potentially disastrous for the tourism industry. The  Since January 2002, the government has had its lines of credit at international financial institutions frozen, through U.S. legislation called the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001 (ZDERA). Section 4C instructs the secretary of the treasury to direct international financial institutions to veto the extension of loans and credit to the Zimbabwean government. According to the United States, these sanctions target only seven specific businesses owned or controlled by government officials and not ordinary citizens.

Zimbabwe maintained positive economic growth throughout the 1980s (5% GDP growth per year) and 1990s (4.3% GDP growth per year). The economy declined from 2000: 5% decline in 2000, 8% in 2001, 12% in 2002 and 18% in 2003. Zimbabwe's involvement from 1998 to 2002 in the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo drained hundreds of millions of dollars from the economy. From 1999 to 2009, Zimbabwe saw the lowest ever economic growth with an annual GDP decrease of 6.1%. The downward spiral of the economy has been attributed mainly to mismanagement and corruption by the government and the eviction of more than 4,000 white farmers in the controversial land confiscations of 2000.Robinson, Simon (18 February 2002)

Since January 2002, the government has had its lines of credit at international financial institutions frozen, through U.S. legislation called the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001 (ZDERA). Section 4C instructs the secretary of the treasury to direct international financial institutions to veto the extension of loans and credit to the Zimbabwean government. According to the United States, these sanctions target only seven specific businesses owned or controlled by government officials and not ordinary citizens.

Zimbabwe maintained positive economic growth throughout the 1980s (5% GDP growth per year) and 1990s (4.3% GDP growth per year). The economy declined from 2000: 5% decline in 2000, 8% in 2001, 12% in 2002 and 18% in 2003. Zimbabwe's involvement from 1998 to 2002 in the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo drained hundreds of millions of dollars from the economy. From 1999 to 2009, Zimbabwe saw the lowest ever economic growth with an annual GDP decrease of 6.1%. The downward spiral of the economy has been attributed mainly to mismanagement and corruption by the government and the eviction of more than 4,000 white farmers in the controversial land confiscations of 2000.Robinson, Simon (18 February 2002)

"A Tale of Two Countries"

''

''Independent Online'', South Africa, 2 February 2010. They have the potential to improve the fiscal situation of the country considerably, but almost all revenues from the field have disappeared into the pockets of army officers and ZANU–PF politicians. In terms of carats produced, the Marange field is one of the largest diamond-producing projects in the world,

, '' Kitco'', 20 August 2013. estimated to have produced 12 million carats in 2014 worth over $350 million. ,

Biggest Zimbabwe Gold Miner to Rule on London Trade by March

Bloomberg News, 17 October 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2016. In 2015, Zimbabwe's gold production is 20 metric tonnes.

Zimbabwe's commercial farming sector was traditionally a source of exports and foreign exchange and provided 400,000 jobs. However, the government's land reform program badly damaged the sector, turning Zimbabwe into a net importer of food products. For example, between 2000 and 2016, annual wheat production fell from 250,000 tons to 60,000 tons, maize was reduced from two million tons to 500,000 tons and cattle slaughtered for beef fell from 605,000 head to 244,000 head. Coffee production, once a prized export commodity, came to a virtual halt after seizure or expropriation of white-owned coffee farms in 2000 and has never recovered.

For the past ten years, the

Zimbabwe's commercial farming sector was traditionally a source of exports and foreign exchange and provided 400,000 jobs. However, the government's land reform program badly damaged the sector, turning Zimbabwe into a net importer of food products. For example, between 2000 and 2016, annual wheat production fell from 250,000 tons to 60,000 tons, maize was reduced from two million tons to 500,000 tons and cattle slaughtered for beef fell from 605,000 head to 244,000 head. Coffee production, once a prized export commodity, came to a virtual halt after seizure or expropriation of white-owned coffee farms in 2000 and has never recovered.

For the past ten years, the

Since the land reform programme in 2000, tourism in Zimbabwe has steadily declined. In 2018, tourism peaked with 2.6 million tourists. In 2016, the total contribution of tourism to Zimbabwe was $1.1 billion (USD), or about 8.1% of Zimbabwe's GDP. Employment in travel and tourism, as well as the industries indirectly supported by travel and tourism, was 5.2% of national employment.

Several airlines pulled out of Zimbabwe between 2000 and 2007. Australia's

Since the land reform programme in 2000, tourism in Zimbabwe has steadily declined. In 2018, tourism peaked with 2.6 million tourists. In 2016, the total contribution of tourism to Zimbabwe was $1.1 billion (USD), or about 8.1% of Zimbabwe's GDP. Employment in travel and tourism, as well as the industries indirectly supported by travel and tourism, was 5.2% of national employment.

Several airlines pulled out of Zimbabwe between 2000 and 2007. Australia's

According to the 2022 census report, 99.6% of the population is of African origin. The majority people, the Shona, comprise 82%, while Ndebele make up 14% of the population. The Ndebele descended from Zulu migrations in the 19th century and the other tribes with which they intermarried. Up to one million Ndebele may have left the country over the last five years, mainly for South Africa. Other ethnic groups include

According to the 2022 census report, 99.6% of the population is of African origin. The majority people, the Shona, comprise 82%, while Ndebele make up 14% of the population. The Ndebele descended from Zulu migrations in the 19th century and the other tribes with which they intermarried. Up to one million Ndebele may have left the country over the last five years, mainly for South Africa. Other ethnic groups include

In August 2008 large areas of Zimbabwe were struck by the ongoing cholera epidemic. By December 2008 more than 10,000 people had been infected in all but one of Zimbabwe's provinces, and the outbreak had spread to Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia."Miliband backs African calls for end of Mugabe"

In August 2008 large areas of Zimbabwe were struck by the ongoing cholera epidemic. By December 2008 more than 10,000 people had been infected in all but one of Zimbabwe's provinces, and the outbreak had spread to Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia."Miliband backs African calls for end of Mugabe"

''

IRIN. 9 March 2009 In Harare, the city council offered free graves to cholera victims.

Large investments in education since independence has resulted in the highest adult literacy rate in Africa which in 2013 was 90.70%. This is lower than the 92% recorded in 2010 by the

Large investments in education since independence has resulted in the highest adult literacy rate in Africa which in 2013 was 90.70%. This is lower than the 92% recorded in 2010 by the

Zimbabwe has many different cultures, with Shona beliefs and ceremonies being prominent. The Shona people have many types of sculptures and carvings.

Zimbabwe first celebrated its independence on 18 April 1980. Celebrations are held at either the National Sports Stadium or

Zimbabwe has many different cultures, with Shona beliefs and ceremonies being prominent. The Shona people have many types of sculptures and carvings.

Zimbabwe first celebrated its independence on 18 April 1980. Celebrations are held at either the National Sports Stadium or

Traditional arts in Zimbabwe include

Traditional arts in Zimbabwe include

Like in many African countries, the majority of Zimbabweans depend on a few staple foods. "Mealie meal", also known as cornmeal, is used to prepare ''Ugali, sadza'' or ''isitshwala'', as well as porridge known as ''bota'' or ''ilambazi''. ''Sadza'' is made by mixing the cornmeal with water to produce a thick paste/porridge. After the paste has been cooking for several minutes, more cornmeal is added to thicken the paste. This is usually eaten as lunch or dinner, usually with sides such as gravy, vegetables (spinach, chomolia, or spring greens/collard greens), beans, and meat (stewed, grilled, roasted, or sundried). ''Sadza'' is also commonly eaten with curdled milk (Soured milk, sour milk), commonly known as "lacto" (''mukaka wakakora''), or dried Kapenta, Tanganyika sardine, known locally as ''kapenta'' or ''matemba''. ''Bota'' is a thinner porridge, cooked without the additional cornmeal and usually flavoured with peanut butter, milk, butter, or jam. ''Bota'' is usually eaten for breakfast.

Graduations, weddings, and any other family gatherings will usually be celebrated with the killing of a goat or cow, which will be barbecued or roasted by the family.

Like in many African countries, the majority of Zimbabweans depend on a few staple foods. "Mealie meal", also known as cornmeal, is used to prepare ''Ugali, sadza'' or ''isitshwala'', as well as porridge known as ''bota'' or ''ilambazi''. ''Sadza'' is made by mixing the cornmeal with water to produce a thick paste/porridge. After the paste has been cooking for several minutes, more cornmeal is added to thicken the paste. This is usually eaten as lunch or dinner, usually with sides such as gravy, vegetables (spinach, chomolia, or spring greens/collard greens), beans, and meat (stewed, grilled, roasted, or sundried). ''Sadza'' is also commonly eaten with curdled milk (Soured milk, sour milk), commonly known as "lacto" (''mukaka wakakora''), or dried Kapenta, Tanganyika sardine, known locally as ''kapenta'' or ''matemba''. ''Bota'' is a thinner porridge, cooked without the additional cornmeal and usually flavoured with peanut butter, milk, butter, or jam. ''Bota'' is usually eaten for breakfast.

Graduations, weddings, and any other family gatherings will usually be celebrated with the killing of a goat or cow, which will be barbecued or roasted by the family.

Even though the Afrikaners are a small group (10%) within the white minority group, Afrikaner recipes are popular. ''Biltong'', a type of jerky, is a popular snack, prepared by hanging bits of spiced raw meat to dry in the shade. ''Boerewors'' is served with ''sadza''. It is a long sausage, often well-spiced, composed of beef and any other meat like pork, and barbecued.

As Zimbabwe was a British colony, some people there have adopted some colonial-era English eating habits. For example, most people will have porridge in the morning, as well as 10 o'clock tea (midday tea). They will have lunch, often leftovers from the night before, freshly cooked ''sadza'', or sandwiches (which is more common in the cities). After lunch, there is usually 4 o'clock tea (afternoon tea), which is served before dinner. It is not uncommon for tea to be had after dinner.

Rice, pasta, and Potato production in Zimbabwe, potato-based foods (French fries and mashed potato) also make up part of Zimbabwean cuisine. A local favourite is rice cooked with peanut butter, which is taken with thick gravy, mixed vegetables and meat. A potpourri of peanuts known as ''nzungu'', boiled and sundried maize, black-eyed peas known as ''nyemba'', and Vigna subterranea, Bambara groundnuts known as ''nyimo'' makes a traditional dish called ''mutakura''.

Even though the Afrikaners are a small group (10%) within the white minority group, Afrikaner recipes are popular. ''Biltong'', a type of jerky, is a popular snack, prepared by hanging bits of spiced raw meat to dry in the shade. ''Boerewors'' is served with ''sadza''. It is a long sausage, often well-spiced, composed of beef and any other meat like pork, and barbecued.

As Zimbabwe was a British colony, some people there have adopted some colonial-era English eating habits. For example, most people will have porridge in the morning, as well as 10 o'clock tea (midday tea). They will have lunch, often leftovers from the night before, freshly cooked ''sadza'', or sandwiches (which is more common in the cities). After lunch, there is usually 4 o'clock tea (afternoon tea), which is served before dinner. It is not uncommon for tea to be had after dinner.

Rice, pasta, and Potato production in Zimbabwe, potato-based foods (French fries and mashed potato) also make up part of Zimbabwean cuisine. A local favourite is rice cooked with peanut butter, which is taken with thick gravy, mixed vegetables and meat. A potpourri of peanuts known as ''nzungu'', boiled and sundried maize, black-eyed peas known as ''nyemba'', and Vigna subterranea, Bambara groundnuts known as ''nyimo'' makes a traditional dish called ''mutakura''.

Football ''(also known as soccer)'' is the most popular sport in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe national football team, The Warriors have qualified for the Africa Cup of Nations five times (2004, 2006, 2017, 2019, 2021), and won the COSAFA Cup, Southern Africa championship on six occasions (2000, 2003, 2005, 2009, 2017, 2018) and the CECAFA Cup, Eastern Africa cup once (1985). The team is ranked 68th in 2022.

Rugby union is a significant sport in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe national rugby union team, The national side have represented the country at 2 Rugby World Cup tournaments in 1987 and 1991.

Cricket is also a very popular sport in Zimbabwe. It used to have a following mostly among the white minority, but it has recently grown to become a widely popular sport among most Zimbabweans. It is one of twelve Test cricket playing nations and an International Cricket Council, ICC full member as well. Notable cricket players from Zimbabwe include Andy Flower, Heath Streak,Brendan Taylor and Sikandar Raza.

Zimbabwe has won eight Olympic medals, one in field hockey Zimbabwe women's national field hockey team, with the women's team at the Zimbabwe at the 1980 Summer Olympics, 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and seven by swimmer Kirsty Coventry, three at the Zimbabwe at the 2004 Summer Olympics, 2004 Summer Olympics and four at the Zimbabwe at the 2008 Summer Olympics, 2008 Summer Olympics. Zimbabwe has done well in the Commonwealth Games and All-Africa Games in swimming with Coventry obtaining 11 gold medals in the different competitions. Zimbabwe has competed at Wimbledon Championships, Wimbledon and the Davis Cup in tennis, most notably with the Black family, which comprises Wayne Black, Byron Black and Cara Black. The Zimbabwean Nick Price held the official World Number 1 golf status longer than any player from Africa has done.

Other sports played in Zimbabwe are basketball, volleyball, netball, and water polo, as well as Squash (sport), squash, motorsport, martial arts, chess, cycling, polocrosse, kayaking and horse racing. However, most of these sports do not have international representatives but instead stay at a junior or national level.

Zimbabwean professional rugby league players playing overseas are Masimbaashe Motongo and Judah Mazive. Former players include now SANZAAR CEO Andy Marinos who made an appearance for South Africa national rugby league team, South Africa at the Super League World Nines and featured for the Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs, Sydney Bulldogs as well as Zimbabwe-born former Scotland national rugby union team, Scotland rugby union international Scott Gray (rugby union), Scott Gray, who spent time at the Brisbane Broncos.

Zimbabwe has had success in karate as Zimbabwe's Samson Muripo became Kyokushin world champion in Osaka, Japan in 2009. Muripo is a two-time World Kyokushi Karate Champion and was the first black African to become the World Kyokushin Karate Champion.

Football ''(also known as soccer)'' is the most popular sport in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe national football team, The Warriors have qualified for the Africa Cup of Nations five times (2004, 2006, 2017, 2019, 2021), and won the COSAFA Cup, Southern Africa championship on six occasions (2000, 2003, 2005, 2009, 2017, 2018) and the CECAFA Cup, Eastern Africa cup once (1985). The team is ranked 68th in 2022.

Rugby union is a significant sport in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe national rugby union team, The national side have represented the country at 2 Rugby World Cup tournaments in 1987 and 1991.

Cricket is also a very popular sport in Zimbabwe. It used to have a following mostly among the white minority, but it has recently grown to become a widely popular sport among most Zimbabweans. It is one of twelve Test cricket playing nations and an International Cricket Council, ICC full member as well. Notable cricket players from Zimbabwe include Andy Flower, Heath Streak,Brendan Taylor and Sikandar Raza.

Zimbabwe has won eight Olympic medals, one in field hockey Zimbabwe women's national field hockey team, with the women's team at the Zimbabwe at the 1980 Summer Olympics, 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and seven by swimmer Kirsty Coventry, three at the Zimbabwe at the 2004 Summer Olympics, 2004 Summer Olympics and four at the Zimbabwe at the 2008 Summer Olympics, 2008 Summer Olympics. Zimbabwe has done well in the Commonwealth Games and All-Africa Games in swimming with Coventry obtaining 11 gold medals in the different competitions. Zimbabwe has competed at Wimbledon Championships, Wimbledon and the Davis Cup in tennis, most notably with the Black family, which comprises Wayne Black, Byron Black and Cara Black. The Zimbabwean Nick Price held the official World Number 1 golf status longer than any player from Africa has done.

Other sports played in Zimbabwe are basketball, volleyball, netball, and water polo, as well as Squash (sport), squash, motorsport, martial arts, chess, cycling, polocrosse, kayaking and horse racing. However, most of these sports do not have international representatives but instead stay at a junior or national level.

Zimbabwean professional rugby league players playing overseas are Masimbaashe Motongo and Judah Mazive. Former players include now SANZAAR CEO Andy Marinos who made an appearance for South Africa national rugby league team, South Africa at the Super League World Nines and featured for the Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs, Sydney Bulldogs as well as Zimbabwe-born former Scotland national rugby union team, Scotland rugby union international Scott Gray (rugby union), Scott Gray, who spent time at the Brisbane Broncos.

Zimbabwe has had success in karate as Zimbabwe's Samson Muripo became Kyokushin world champion in Osaka, Japan in 2009. Muripo is a two-time World Kyokushi Karate Champion and was the first black African to become the World Kyokushin Karate Champion.

''International Freedom of Expression Exchange'', 28 May 2010. In June 2010 ''NewsDay (Zimbabwean newspaper), NewsDay'' became the first independent daily newspaper to be published in Zimbabwe in seven years. The

"The nine lives of Wilf Mbanga"

''The London Globe'' via ''Metrovox''. As a result, many press organisations have been set up in both neighbouring and Western countries by exiled Zimbabweans. Because the internet is unrestricted, many Zimbabweans are allowed to access online news sites set up by exiled journalists. Reporters Without Borders claims the media environment in Zimbabwe involves "surveillance, threats, imprisonment, censorship, blackmail, abuse of power and denial of justice are all brought to bear to keep firm control over the news." In its 2021 report, Reporters Without Borders ranked the Zimbabwean media as 130th out of 180, noting that "access to information has improved and self-censorship has declined, but journalists are still often attacked or arrested". The government also bans many foreign broadcasting stations from Zimbabwe, including the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, CBC, Sky News, Channel 4, American Broadcasting Company, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and Fox News. News agencies and newspapers from other Western countries and South Africa have also been banned from the country.

The stone-carved Zimbabwe Bird appears on the national flags and the coats of arms of both Zimbabwe and Rhodesia, as well as on Rhodesian dollar, banknotes and coins (first on Coins of the Rhodesian pound, Rhodesian pound and then Coins of the Rhodesian dollar, Rhodesian dollar). It probably represents the Bateleur, bateleur eagle or the African fish eagle. The famous soapstone bird carvings stood on walls and monoliths of the ancient city of Great Zimbabwe.

Balancing rocks of Zimbabwe, Balancing rocks are geological formations all over Zimbabwe. The rocks are perfectly balanced without other supports. They are created when ancient granite intrusions are exposed to weathering, as softer rocks surrounding them erode away. They have been depicted on both the banknotes of Zimbabwe and the Rhodesian dollar banknotes. The ones found on the current notes of Zimbabwe, named the Banknote Rocks, are located in Epworth, Zimbabwe, Epworth, approximately southeast of Harare. There are many different formations of the rocks, incorporating single and paired columns of three or more rocks. These formations are a feature of south and east tropical Africa from northern South Africa northwards to Sudan. The most notable formations in Zimbabwe are located in the Matobo National Park in Matabeleland.

The national anthem of Zimbabwe is "Raise the Flag of Zimbabwe" (; ). It was introduced in March 1994 after a nationwide competition to replace as a distinctly Zimbabwean song. The winning entry was a song written by Professor Solomon Mutswairo and composed by Fred Changundega. It has been translated into all three of the main languages of Zimbabwe.

The stone-carved Zimbabwe Bird appears on the national flags and the coats of arms of both Zimbabwe and Rhodesia, as well as on Rhodesian dollar, banknotes and coins (first on Coins of the Rhodesian pound, Rhodesian pound and then Coins of the Rhodesian dollar, Rhodesian dollar). It probably represents the Bateleur, bateleur eagle or the African fish eagle. The famous soapstone bird carvings stood on walls and monoliths of the ancient city of Great Zimbabwe.

Balancing rocks of Zimbabwe, Balancing rocks are geological formations all over Zimbabwe. The rocks are perfectly balanced without other supports. They are created when ancient granite intrusions are exposed to weathering, as softer rocks surrounding them erode away. They have been depicted on both the banknotes of Zimbabwe and the Rhodesian dollar banknotes. The ones found on the current notes of Zimbabwe, named the Banknote Rocks, are located in Epworth, Zimbabwe, Epworth, approximately southeast of Harare. There are many different formations of the rocks, incorporating single and paired columns of three or more rocks. These formations are a feature of south and east tropical Africa from northern South Africa northwards to Sudan. The most notable formations in Zimbabwe are located in the Matobo National Park in Matabeleland.

The national anthem of Zimbabwe is "Raise the Flag of Zimbabwe" (; ). It was introduced in March 1994 after a nationwide competition to replace as a distinctly Zimbabwean song. The winning entry was a song written by Professor Solomon Mutswairo and composed by Fred Changundega. It has been translated into all three of the main languages of Zimbabwe.

excerpt and text search

* . * Smith, Ian Douglas. ''Bitter Harvest: Zimbabwe and the Aftermath of its Independence'' (2008

excerpt and text search

* David Coltart. The struggle continues: 50 Years of Tyranny in Zimbabwe. Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd: South Africa, 2016.

Official Government of Zimbabwe web portal

.

Parliament of Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe profile

from the

Zimbabwe

''The World Factbook''. Central Intelligence Agency.

Zimbabwe

from ''UCB Libraries GovPubs''

Key Development Forecasts for Zimbabwe

from International Futures

World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Zimbabwe

{{Coord, 19, S, 30, E, type:country_region:ZW, display=title Zimbabwe, 1980 establishments in Zimbabwe Countries and territories where English is an official language Former British colonies and protectorates in Africa G15 nations Landlocked countries Member states of the African Union Member states of the United Nations Republics East African countries Southeast African countries Southern African countries States and territories established in 1980 Countries in Africa

landlocked country

A landlocked country is a country that has no territory connected to an ocean or whose coastlines lie solely on endorheic basins. Currently, there are 44 landlocked countries, two of them doubly landlocked (Liechtenstein and Uzbekistan), and t ...

in Southeast Africa

Southeast Africa, or Southeastern Africa, is an African region that is intermediate between East Africa and Southern Africa. It comprises the countries Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanza ...

, between the Zambezi

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than half of t ...

and Limpopo River

The Limpopo River () rises in South Africa and flows generally eastward through Mozambique to the Indian Ocean. The term Limpopo is derived from Rivombo (Livombo/Lebombo), a group of Tsonga settlers led by Hosi Rivombo who settled in the mou ...

s, bordered by South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

to the south, Botswana

Botswana, officially the Republic of Botswana, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. Botswana is topographically flat, with approximately 70 percent of its territory part of the Kalahari Desert. It is bordered by South Africa to the sou ...

to the southwest, Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

to the north, and Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

to the east. The capital and largest city is Harare

Harare ( ), formerly Salisbury, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of , a population of 1,849,600 as of the 2022 Zimbabwe census, 2022 census and an estimated 2,487,209 people in its metrop ...

, and the second largest is Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; ) is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council claimed it to be about ...

.

A country of roughly 16.6 million people as per 2024 census, Zimbabwe's largest ethnic group are the Shona

Shona often refers to:

* Shona people, a Southern African people

** Shona language, a Bantu language spoken by Shona people today

** Shona languages, a wider group of languages defined in the early 20th century

** Kingdom of Zimbabwe, a Shona stat ...

, who make up 80% of the population, followed by the Northern Ndebele and other smaller minorities. Zimbabwe has 16 official language

An official language is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as, "the language or one of the languages that is accepted by a country's government, is taught in schools, used in the courts of law, etc." Depending on the decree, establishmen ...

s, with English, Shona

Shona often refers to:

* Shona people, a Southern African people

** Shona language, a Bantu language spoken by Shona people today

** Shona languages, a wider group of languages defined in the early 20th century

** Kingdom of Zimbabwe, a Shona stat ...

, and Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe

* Sumayela Ndebele (Northern Transvaal Ndebele), located in South Africa

Languages

*Southern Ndebele language, the language of ...

the most common. Zimbabwe is a member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, the Southern African Development Community

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is an inter-governmental organization headquartered in Gaborone, Botswana.

Goals

The SADC's goal is to further regional socio-economic cooperation and integration as well as political and se ...

, the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

, and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) is a regional economic community in Africa with twenty-one member states stretching from Tunisia to Eswatini. COMESA was formed in December 1994, replacing a Preferential Trade Area whi ...

.

The region was long inhabited by the San, and was settled by Bantu peoples

The Bantu peoples are an Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous ethnolinguistic grouping of approximately 400 distinct native Demographics of Africa, African List of ethnic groups of Africa, ethnic groups who speak Bantu languages. The language ...

around 2,000 years ago. Beginning in the 11th century the Shona people

The Shona people () also/formerly known as the Karanga are a Bantu peoples, Bantu ethnic group native to Southern Africa, primarily living in Zimbabwe where they form the majority of the population, as well as Mozambique, South Africa, and world ...

constructed the city of Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe was a city in the south-eastern hills of the modern country of Zimbabwe, near Masvingo. It was settled from 1000 AD, and served as the capital of the Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe from the 13th century. It is the largest stone struc ...

, which became one of the major African trade centres by the 13th century. From there, the Kingdom of Zimbabwe

The Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe was a Shona kingdom located in modern-day Zimbabwe. Its capital was Great Zimbabwe, the largest stone structure in precolonial Southern Africa, which had a population of 10,000. Around 1300, Great Zimbabwe repl ...

was established, followed by the Mutapa and Rozvi

The Rozvi Empire (1490–?, 17th century–1866) was a Shona state established on the Zimbabwean Plateau. The term "Rozvi" refers to their legacy as a warrior nation, taken from the Shona term ''kurozva'', "to plunder". They became the most ...

empires. The British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

demarcated the Rhodesia region in 1890 when they conquered Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northeastern Zimbabwe. It is home to nearly half of the population of Zimbabwe. The majority of the Mashonaland people are from the Shona tribe while the Zezuru and Korekore dialects are most common. Harare is the larg ...

and later in 1893 Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambezi ...

after the First Matabele War

The First Matabele War was fought between 1893 and 1894 in modern-day Zimbabwe. It pitted the British South Africa Company against the Ndebele (Matabele) Kingdom. Lobengula, king of the Ndebele, had tried to avoid outright war with the compa ...

. Company rule

Company rule in India (also known as the Company Raj, from Hindi , ) refers to regions of the Indian subcontinent under the control of the British East India Company (EIC). The EIC, founded in 1600, established its first trading post in India ...

ended in 1923 with the establishment of Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

as a self-governing British colony. In 1965, the white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

minority government unilaterally declared independence as Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

. The state endured international isolation and a 15-year guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrorism ...

with black nationalist forces; this culminated in a peace agreement

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surr ...

that established ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' sovereignty as Zimbabwe in April 1980.

Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of th ...

became Prime Minister of Zimbabwe

The prime minister of Zimbabwe was a political office in the government of Zimbabwe that existed on two occasions. The first person to hold the position was Robert Mugabe from 1980 to 1987 following independence from the United Kingdom. He to ...

in 1980, when his ZANU–PF

The Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF) is a political organisation which has been the ruling party of Zimbabwe since independence in 1980. The party was led for many years by Robert Mugabe, first as prime minister wi ...

party won the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

following the end of white minority rule and has remained the country's dominant party since. He was the President of Zimbabwe from 1987, after converting the country's initial parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their Election, democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of t ...

into a presidential one, until his resignation in 2017. Under Mugabe's authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

regime, the state security apparatus dominated the country and was responsible for widespread human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

violations, which received worldwide condemnation. From 1997 to 2008, the economy experienced consistent decline (and in the latter years, hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real versus nominal value (economics), real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimiz ...

), though it has since seen rapid growth after the use of currencies other than the Zimbabwean dollar

The Zimbabwean dollar (sign: $, or Z$ to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies) was the name of four official currencies of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 12 April 2009. During this time, it was subject to periods of extreme inflat ...

was permitted. In 2017, in the wake of over a year of protests against his government as well as Zimbabwe's rapidly declining economy, a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

resulted in Mugabe's resignation. Emmerson Mnangagwa

Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa ( , ; born 15 September 1942) is a Zimbabwean politician who has served as the president of Zimbabwe since 2017. A member of ZANU–PF and a longtime ally of former president Robert Mugabe, he held a series of cabin ...

has since served as Zimbabwe's president.

Etymology

The name "Zimbabwe" stems from aShona

Shona often refers to:

* Shona people, a Southern African people

** Shona language, a Bantu language spoken by Shona people today

** Shona languages, a wider group of languages defined in the early 20th century

** Kingdom of Zimbabwe, a Shona stat ...

term for Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe was a city in the south-eastern hills of the modern country of Zimbabwe, near Masvingo. It was settled from 1000 AD, and served as the capital of the Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe from the 13th century. It is the largest stone struc ...

, a medieval city (Masvingo

Masvingo, known as Fort Victoria during the colonial period, is a city in southeastern Zimbabwe and the capital of Masvingo Province. The city lies close to Great Zimbabwe, the national monument from which the country takes its name and clos ...

) in the country's south-east. Two different theories address the origin of the word. Many sources hold that "Zimbabwe" derives from ''dzimba-dza-mabwe'', translated from the Karanga dialect of Shona as "houses of stones" (''dzimba'' = plural of '' imba'', "house"; ''mabwe'' = plural of '' ibwe'', "stone"). The Karanga-speaking Shona people live around Great Zimbabwe in the modern-day Masvingo

Masvingo, known as Fort Victoria during the colonial period, is a city in southeastern Zimbabwe and the capital of Masvingo Province. The city lies close to Great Zimbabwe, the national monument from which the country takes its name and clos ...

province. Archaeologist Peter Garlake claims that "Zimbabwe" represents a contracted form of ''dzimba-hwe'', which means "venerated houses" in the Zezuru dialect of Shona and usually references chiefs' houses or graves.

Zimbabwe was formerly known as Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

(1898), Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

(1965), and Zimbabwe Rhodesia

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (), alternatively known as Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, was a short-lived unrecognised sovereign state that existed from 1 June 1979 to 18 April 1980, though it lacked international recog ...

(1979). The first recorded use of "Zimbabwe" as a term of national reference dates from 1960 as a coinage by the black nationalist Michael Mawema, whose Zimbabwe National Party became the first to officially use the name in 1961. The term "Rhodesia"—derived from the surname of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, the primary instigator of British colonisation of the territory—was perceived by African nationalists as inappropriate because of its colonial origin and connotations.

According to Mawema, black nationalists held a meeting in 1960 to choose an alternative name for the country, proposing names such as "Matshobana" and " Monomotapa" before his suggestion, "Zimbabwe", prevailed. It was initially unclear how the chosen term was to be used—a letter written by Mawema in 1961 refers to "Zimbabweland" — but "Zimbabwe" was sufficiently established by 1962 to become the generally preferred term of the black nationalist movement.

Like those of many African countries that gained independence during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, ''Zimbabwe'' is an ethnically neutral name. It is debatable to what extent Zimbabwe, being over 80% homogenously Shona

Shona often refers to:

* Shona people, a Southern African people

** Shona language, a Bantu language spoken by Shona people today

** Shona languages, a wider group of languages defined in the early 20th century

** Kingdom of Zimbabwe, a Shona stat ...

and dominated by them in various ways, can be described as a nation state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the State (polity), state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly ...

. The constitution acknowledges 16 languages, but only embraces two of them nationally, Shona and English. Shona is taught widely in schools, unlike Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe

* Sumayela Ndebele (Northern Transvaal Ndebele), located in South Africa

Languages

*Southern Ndebele language, the language of ...

. Zimbabwe has additionally never had a non-Shona head of state.

History

Pre-colonial era

Archaeological records date archaic human settlement of present-day Zimbabwe to at least 500,000 years ago. Zimbabwe's earliest known inhabitants were most likely theSan people

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are the members of any of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region. They are thought to have diverged from other humans 100,000 to 200 ...

, who left behind a legacy of arrowheads and cave paintings. Approximately 2,000 years ago, the first Bantu-speaking farmers arrived during the Bantu expansion.

Societies speaking proto-Shona languages

The Shona languages (also called the Shonic group) are a clade of Bantu language

The Bantu languages (English: , Proto-Bantu language, Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀), or Ntu languages are a language family of about 600 languages of Central Africa, ...

first emerged in the middle Limpopo River

The Limpopo River () rises in South Africa and flows generally eastward through Mozambique to the Indian Ocean. The term Limpopo is derived from Rivombo (Livombo/Lebombo), a group of Tsonga settlers led by Hosi Rivombo who settled in the mou ...

valley in the 9th century before moving on to the Zimbabwean highlands. The Zimbabwean plateau became the centre of subsequent Shona states, beginning around the 10th century. Around the early 10th century, trade developed with Arab merchants on the Indian Ocean coast, helping to develop the Kingdom of Mapungubwe

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe (pronounced ) was an ancient state located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers in South Africa, south of Great Zimbabwe. The capital's population was 5,000 by 1250, and the state likely covered 30,000 k ...

in the 13th century. This was the precursor to the Shona civilisations that dominated the region from the 13th century, evidenced by ruins at Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe was a city in the south-eastern hills of the modern country of Zimbabwe, near Masvingo. It was settled from 1000 AD, and served as the capital of the Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe from the 13th century. It is the largest stone struc ...

, near Masvingo

Masvingo, known as Fort Victoria during the colonial period, is a city in southeastern Zimbabwe and the capital of Masvingo Province. The city lies close to Great Zimbabwe, the national monument from which the country takes its name and clos ...

, and by other smaller sites. The main archaeological site used a unique dry stone architecture. The Kingdom of Mapungubwe was the first in a series of trading states which had developed in Zimbabwe by the time the first European explorers arrived from Portugal. These states traded gold, ivory, and copper for cloth and glass.

By 1300, the Kingdom of Zimbabwe

The Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe was a Shona kingdom located in modern-day Zimbabwe. Its capital was Great Zimbabwe, the largest stone structure in precolonial Southern Africa, which had a population of 10,000. Around 1300, Great Zimbabwe repl ...

eclipsed Mapungubwe. This Shona state further refined and expanded upon Mapungubwe's stone architecture. From 1450 to 1760, the Kingdom of Mutapa

The Mutapa Empire – sometimes referred to as Mwenemutapa or Munhumutapa, (, ) – was an African empire in Zimbabwe, which expanded to what is now modern-day Mozambique, Botswana, Malawi, and Zambia. It was ruled by the Nembire or Mbire dyn ...

ruled much of the area of present-day Zimbabwe, plus parts of central Mozambique. It is known by many names including the Mutapa Empire, also known as ''Mwene Mutapa'' or ''Monomotapa'' as well as "Munhumutapa", and was renowned for its strategic trade routes with the Arabs and Portugal. The Portuguese sought to monopolise this influence and began a series of wars which left the empire in near collapse in the early 17th century.

As a direct response to increased European presence in the interior a new Shona state emerged, known as the Rozwi Empire

The Rozvi Empire (1490–?, 17th century–1866) was a Shona state established on the Zimbabwean Plateau. The term "Rozvi" refers to their legacy as a warrior nation, taken from the Shona term ''kurozva'', "to plunder". They became the most ...

. Relying on centuries of military, political and religious development, the Rozwi (meaning "destroyers") expelled the Portuguese from the Zimbabwean plateau in 1683. Around 1821 the Zulu general Mzilikazi

Mzilikazi Moselekatse, Khumalo ( 1790 – 9 September 1868) was a Southern African king who founded the Ndebele Kingdom now called Matebeleland which is now part of Zimbabwe. His name means "the great river of blood". He was born the son of M ...

of the Khumalo clan

The Khumalo are an African clan that originated in northern KwaZulu, South Africa. The Khumalos are part of a group of Zulus and Ngunis known as the Mntungwa. Others include the Blose and Mabaso and Zikode, located between the Ndwandwe and th ...

successfully rebelled against King Shaka

Shaka kaSenzangakhona (–24 September 1828), also known as Shaka (the) Zulu () and Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828. One of the most influential monarchs of the Zulu, he ordered wide-reaching reform ...

and established his own clan, the Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe

* Sumayela Ndebele (Northern Transvaal Ndebele), located in South Africa

Languages

*Southern Ndebele language, the language of ...

. The Ndebele fought their way northwards into the Transvaal

Transvaal is a historical geographic term associated with land north of (''i.e.'', beyond) the Vaal River in South Africa. A number of states and administrative divisions have carried the name ''Transvaal''.

* South African Republic (1856–1902; ...

, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake and beginning an era of widespread devastation known as the Mfecane

The Mfecane, also known by the Sesotho names Difaqane or Lifaqane (all meaning "crushing," "scattering," "forced dispersal," or "forced migration"), was a historical period of heightened military conflict and migration associated with state fo ...

. When Dutch trekboers

The Trekboers ( ) were nomadic pastoralists descended from mostly Dutch colonists on the frontiers of the Dutch Cape Colony in Southern Africa. The Trekboers began migrating into the interior from the areas surrounding what is now Cape Town, ...

converged on the Transvaal in 1836, they drove the tribe even further northward, with the assistance of Tswana

Tswana may refer to:

* Tswana people, the Bantu languages, Bantu speaking people in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other Southern Africa regions

* Tswana language, the language spoken by the (Ba)Tswana people

* Tswanaland, ...

Barolong

The Rolong (pronounced ) are a Tswana ethnic group native to Botswana and South Africa.

Etymology

The Rolong people's name originated from the clan's first ''kgosi'' (king, chief) Morolong, who lived around 1270–1280. The ancient word '' ...

warriors and Griqua

Griqua may refer to:

* Griqua people, of South Africa

* Griqua language or Xiri language, their endangered Khoi language

* Griquas (rugby)

Griquas (), known as the Suzuki Griquas for sponsorship reasons, are a South African professional rugby ...

commandos. By 1838 the Ndebele had conquered the Rozwi Empire, along with the other smaller Shona states, and reduced them to vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

dom.

After losing their remaining South African lands in 1840, Mzilikazi and his tribe permanently settled in the southwest of present-day Zimbabwe in what became known as Matabeleland, establishing

After losing their remaining South African lands in 1840, Mzilikazi and his tribe permanently settled in the southwest of present-day Zimbabwe in what became known as Matabeleland, establishing Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; ) is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council claimed it to be about ...

as their capital. Mzilikazi then organised his society into a military system with regimental kraal

Kraal (also spelled ''craal'' or ''kraul'') is an Afrikaans and Dutch language, Dutch word, also used in South African English, for an pen (enclosure), enclosure for cattle or other livestock, located within a Southern African Human settlement ...

s, similar to those of Shaka, which was stable enough to repel further Boer incursions. Mzilikazi died in 1868; following a violent power struggle, his son Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo ( 1835 – 1894) was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people (historically called Matabele in English). Both names in the Zimbabwean Ndebele language, Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields ...

succeeded him.

Colonial era and Rhodesia (1888–1964)

In the 1880s, European colonists arrived with

In the 1880s, European colonists arrived with Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

's British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

(chartered in 1889). In 1888, Rhodes obtained a concession for mining rights from King Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo ( 1835 – 1894) was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people (historically called Matabele in English). Both names in the Zimbabwean Ndebele language, Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields ...

of the Ndebele peoples.

He presented this concession to persuade the government of the United Kingdom to grant a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

to the company over Matabeleland, and its subject states such as Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northeastern Zimbabwe. It is home to nearly half of the population of Zimbabwe. The majority of the Mashonaland people are from the Shona tribe while the Zezuru and Korekore dialects are most common. Harare is the larg ...

as well. Parsons, pp. 178–81. Rhodes used this document in 1890 to justify sending the Pioneer Column

The Pioneer Column was a force raised by Cecil Rhodes and his British South Africa Company in 1890 and used in his efforts to annex the territory of Mashonaland, later part of Zimbabwe (once Southern Rhodesia).

Background

Rhodes was anxious to ...

, a group of Europeans protected by well-armed British South Africa Police

The British South Africa Police (BSAP) was, for most of its existence, the police force of Southern Rhodesia and Rhodesia (renamed Zimbabwe in 1980). It was formed as a paramilitary force of mounted infantrymen in 1889 by Cecil Rhodes' Britis ...

(BSAP) through Matabeleland and into Shona territory to establish Fort Salisbury (present-day Harare

Harare ( ), formerly Salisbury, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of , a population of 1,849,600 as of the 2022 Zimbabwe census, 2022 census and an estimated 2,487,209 people in its metrop ...

), and thereby establish company rule

Company rule in India (also known as the Company Raj, from Hindi , ) refers to regions of the Indian subcontinent under the control of the British East India Company (EIC). The EIC, founded in 1600, established its first trading post in India ...

over the area. In 1893 and 1894, with the help of their new Maxim

Maxim or Maksim may refer to:

Entertainment

*Maxim (magazine), ''Maxim'' (magazine), an international men's magazine

** Maxim (Australia), ''Maxim'' (Australia), the Australian edition

** Maxim (India), ''Maxim'' (India), the Indian edition

*Maxim ...

guns, the BSAP would go on to defeat the Ndebele in the First Matabele War

The First Matabele War was fought between 1893 and 1894 in modern-day Zimbabwe. It pitted the British South Africa Company against the Ndebele (Matabele) Kingdom. Lobengula, king of the Ndebele, had tried to avoid outright war with the compa ...

. Rhodes additionally sought permission to negotiate similar concessions covering all territory between the Limpopo River and Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika ( ; ) is an African Great Lakes, African Great Lake. It is the world's List of lakes by volume, second-largest freshwater lake by volume and the List of lakes by depth, second deepest, in both cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. ...

, then known as "Zambesia". In accordance with the terms of aforementioned concessions and treaties, mass settlement was encouraged, with the British maintaining control over labour as well as over precious metals and other mineral resources.Bryce, James (2008). ''Impressions of South Africa''. p. 170; .

In 1895, the BSAC adopted the name "Rhodesia" for the territory, in honour of Rhodes. In 1898 "Southern Rhodesia" became the official name for the region south of the Zambezi, which later adopted the name "Zimbabwe". The region to the north, administered separately, was later termed

In 1895, the BSAC adopted the name "Rhodesia" for the territory, in honour of Rhodes. In 1898 "Southern Rhodesia" became the official name for the region south of the Zambezi, which later adopted the name "Zimbabwe". The region to the north, administered separately, was later termed Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in Southern Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North ...

(present-day Zambia). Shortly after the disastrous Rhodes-sponsored Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (Afrikaans: ''Jameson-inval'', , 29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson ...

on the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

, the Ndebele rebelled against white rule, led by their charismatic religious leader, Mlimo. The Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the First Chimurenga, was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region that later became Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The conflict was initially between the British South Africa Company and the Mata ...

of 1896–1897 lasted in Matabeleland until 1896, when Mlimo was assassinated by American scout Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

. Shona agitators staged unsuccessful revolts (known as ''Chimurenga

''Chimurenga'' is a word in Shona. The Ndebele equivalent is not as widely used since most Zimbabweans speak Shona; it is ''Umvukela'', meaning "revolutionary struggle" or uprising. In specific historical terms, it also refers to the Ndebele ...

'') against company rule during 1896 and 1897. Following these failed insurrections, the Rhodes administration subdued the Ndebele and Shona groups and organised the land with a disproportionate bias favouring Europeans, thus displacing many indigenous peoples.

The United Kingdom annexed Southern Rhodesia on 12 September 1923.''Collective Responses to Illegal Acts in International Law: United Nations Action in the Question of Southern Rhodesia'' by Vera Gowlland-Debbas Shortly after annexation, on 1 October 1923, the first constitution for the new Colony of Southern Rhodesia came into force. Under the new constitution, Southern Rhodesia became a self-governing

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any ...

British colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by England, and then Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English and later British Empire. There was usually a governor to represent the Crown, appointed by the British monarch on ...

, subsequent to a 1922 referendum. Rhodesians of all races served on behalf of the United Kingdom during the two World Wars in the early-20th century. Proportional to the white population, Southern Rhodesia contributed more ''per capita'' to both the First

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and Second World Wars

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

than any other part of the empire, including Britain.

The 1930 Land Apportionment Act restricted black land ownership to certain segments of the country, setting aside large areas solely for the purchase of the white minority. This act, which led to rapidly rising inequality, became the subject of frequent calls for subsequent land reform. In 1953, in the face of African opposition, Parsons, p. 292. Britain consolidated the two Rhodesias with Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After ...

(Malawi) in the ill-fated Central African Federation

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

, which Southern Rhodesia essentially dominated. Growing African nationalism

African nationalism is an umbrella term which refers to a group of political ideologies in sub-Saharan Africa, which are based on the idea of national self-determination and the creation of nation states.multiracial democracy Multiracial democracy is a democratic political system that is multiracial. It is cited as aspiration in South Africa after apartheid and as existing for the United States.

See also

* Cultural mosaic

* Ethnopluralism

* Intercultural relations

* ...

was finally introduced to Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Southern Rhodesians of European ancestry continued to enjoy minority rule

In political science, minoritarianism (or minorityism) is a neologism for a political structure or process in which a minority group of a population has a certain degree of primacy in that population's decision making, with legislative power or ...

.

Following Zambian independence (effective from October 1964),

Following Zambian independence (effective from October 1964), Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 191920 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1979. He w ...

's Rhodesian Front

The Rhodesian Front (RF) was a conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. Formed in March 1962 by white Rhodesians opposed to decolonisation and majority rule, it won that December's general election and s ...

government in Salisbury dropped the designation "Southern" in 1964 (once ''Northern Rhodesia'' had changed its name to ''Zambia'', having the word ''Southern'' before the name ''Rhodesia'' became unnecessary and the country simply became known as ''Rhodesia'' afterwards). Intent on effectively repudiating the recently adopted British policy of "no independence before majority rule

No independence before majority rule (abbreviated NIBMAR) was a policy adopted by the British government requiring the implementation of majority rule in a colony, rather than rule by the white colonial minority, before the empire granted inde ...

", Smith issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

(UDI) from the United Kingdom on 11 November 1965. This marked the first such course taken by a rebel British colony since the American declaration of 1776, which Smith and others indeed claimed provided a suitable precedent to their own actions.

Declaration of independence and civil war (1965–1980)

The United Kingdom deemed the Rhodesian declaration an act of rebellion but did not re-establish control by force. The British government petitioned the United Nations for sanctions against Rhodesia pending unsuccessful talks with Smith's administration in 1966 and 1968. In December 1966, the organisation complied, imposing the first mandatory trade embargo on an autonomous state.Hastedt, Glenn P. (2004) ''Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy'', Infobase Publishing, p. 537; . These sanctions were expanded again in 1968. A civil war ensued whenJoshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) ...

's Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant communist organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with ...

(ZAPU) and Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe African National Union

The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was a militant socialist organisation that fought against white-minority rule in Rhodesia, formed as a split from the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) in 1963. ZANU split in 1975 into wings l ...

(ZANU), supported actively by communist powers and neighbouring African nations, initiated guerrilla operations against Rhodesia's predominantly white government. ZAPU was supported by the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

and associated nations such as Cuba, and adopted a Marxist–Leninist ideology; ZANU meanwhile aligned itself with Maoism

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic o ...

and the bloc headed by the People's Republic of China. Smith declared Rhodesia a republic in 1970, following the results of a referendum the previous year, but this went unrecognised internationally. Meanwhile, Rhodesia's internal conflict intensified, eventually forcing him to open negotiations with the militant communists.

In March 1978, Smith reached an accord with three African leaders, led by Bishop Abel Muzorewa

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement t ...

, who offered to leave the white population comfortably entrenched in exchange for the establishment of a biracial democracy. As a result of the Internal Settlement

The Internal Settlement (also called the Salisbury Agreement HC Deb 04 May 1978 vol 949 cc 455–592) was an agreement which was signed on 3 March 1978 between Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith and the moderate African nationalist leaders comp ...

, elections were held in April 1979, concluding with the United African National Council

The United African National Council (UANC) is a political party in Zimbabwe. It was briefly the ruling party during 1979–1980, when its leader Abel Muzorewa was prime minister.

History

The party was founded by Muzorewa in 1971. Running as Afr ...

(UANC) carrying a majority of parliamentary seats. On 1 June 1979, Muzorewa, the UANC head, became prime minister and the country's name was changed to Zimbabwe Rhodesia. The Internal Settlement left control of the Rhodesian Security Forces

The Rhodesian Security Forces were the military forces of the Rhodesian government. The Rhodesian Security Forces consisted of a ground force (the Rhodesian Army), the Rhodesian Air Force, the British South Africa Police, and various personnel ...

, civil service, judiciary, and a third of parliament seats to whites. On 12 June, the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

voted to lift economic pressure on the former Rhodesia.

Following the fifth Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, held in Lusaka

Lusaka ( ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was abo ...

, Zambia, from 1 to 7 August in 1979, the British government invited Muzorewa, Mugabe, and Nkomo to participate in a constitutional conference at Lancaster House

Lancaster House (originally known as York House and then Stafford House) is a mansion on The Mall, London, The Mall in the St James's district in the West End of London. Adjacent to The Green Park, it is next to Clarence House and St James ...

. The purpose of the conference was to discuss and reach an agreement on the terms of an independence constitution, and provide for elections supervised under British authority allowing Zimbabwe Rhodesia to proceed to legal independence.Chung, Fay (2006). Re-living the Second Chimurenga: memories from the liberation struggle in Zimbabwe