Yugoslav Committee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Yugoslav Committee (, , ) was a

The Yugoslav Committee (, , ) was a

The idea of South Slavic political unity predates the

The idea of South Slavic political unity predates the

In October 1914, Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić learnt the

In October 1914, Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić learnt the

The Serbian leadership considered World War I to be an opportunity for territorial expansion beyond the Serb-inhabited areas of the

The Serbian leadership considered World War I to be an opportunity for territorial expansion beyond the Serb-inhabited areas of the

The Entente Powers ultimately concluded an alliance with Italy by offering it large areas of Austria-Hungary that were inhabited by South Slavs, mostly Croats and Slovenes, along the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea. The offer was formalised as the 1915 Treaty of London, and caused Trumbić and Supilo to reconsider their criticism of Serbian policies. This was because they saw potential Serbian war success against Austria-Hungary as the only realistic safeguard against Italian expansion into the Slovene-and-Croat-inhabited lands. Supilo was convinced Croatia would be partitioned between Italy, Serbia, and Hungary if the Treaty of London was to be implemented.

The matter became closely related to the Entente's simultaneous efforts to obtain an alliance with Bulgaria, or at least to secure its neutrality, in return for territorial gains against Serbia. As compensation, Serbia was promised territories that were within Austria-Hungary at the time: Bosnia and Herzegovina and an outlet to the Adriatic Sea in Dalmatia. Regardless of the promised compensation, Pašić was reluctant to accede to all of the Bulgarian territorial demands, especially before Serbia had secured the new territories. Supilo obtained British support for plebiscites in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Dalmatia so the populace of those territories would decide on their own fate rather than Britain supplying guarantees of westward territorial expansion to Serbia. Crucially, Serbia received Russian support for its dismissal of the proposed land swap.

The Entente Powers ultimately concluded an alliance with Italy by offering it large areas of Austria-Hungary that were inhabited by South Slavs, mostly Croats and Slovenes, along the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea. The offer was formalised as the 1915 Treaty of London, and caused Trumbić and Supilo to reconsider their criticism of Serbian policies. This was because they saw potential Serbian war success against Austria-Hungary as the only realistic safeguard against Italian expansion into the Slovene-and-Croat-inhabited lands. Supilo was convinced Croatia would be partitioned between Italy, Serbia, and Hungary if the Treaty of London was to be implemented.

The matter became closely related to the Entente's simultaneous efforts to obtain an alliance with Bulgaria, or at least to secure its neutrality, in return for territorial gains against Serbia. As compensation, Serbia was promised territories that were within Austria-Hungary at the time: Bosnia and Herzegovina and an outlet to the Adriatic Sea in Dalmatia. Regardless of the promised compensation, Pašić was reluctant to accede to all of the Bulgarian territorial demands, especially before Serbia had secured the new territories. Supilo obtained British support for plebiscites in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Dalmatia so the populace of those territories would decide on their own fate rather than Britain supplying guarantees of westward territorial expansion to Serbia. Crucially, Serbia received Russian support for its dismissal of the proposed land swap.

Supilo thought the Yugoslav Committee had to confront Italian and Hungarian attempts to encroach on lands inhabited by South Slavs and the Greater Serbian expansionist designs pursued by Pašić. While most of the committee agreed with Supilo, they did not want to openly confront Serbia until the South Slavic lands were safe from Italian and Hungarian threats. Following the Serbian military defeat in the 1915 Serbian campaign, Supilo, Gazzari, and Trinajstić concluded the Serb members of the Yugoslav Committee believed the proposed unification should primarily encompass ethnic Serbs in a centralised state and saw no need for a federal system because they deemed differences between Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes to be the artificial result of Austrian rule. Supilo protested by informing the Yugoslav Committee he had sent a memo to Grey, proposing an independent Croatian state should be established unless Serbia agreed to treat Croats and Slovenes as equal to Serbs. His principal complaint was that the Entente Powers thought of Croatia and other Austro-Hungarian territories as compensation to Serbia for the loss of

Supilo thought the Yugoslav Committee had to confront Italian and Hungarian attempts to encroach on lands inhabited by South Slavs and the Greater Serbian expansionist designs pursued by Pašić. While most of the committee agreed with Supilo, they did not want to openly confront Serbia until the South Slavic lands were safe from Italian and Hungarian threats. Following the Serbian military defeat in the 1915 Serbian campaign, Supilo, Gazzari, and Trinajstić concluded the Serb members of the Yugoslav Committee believed the proposed unification should primarily encompass ethnic Serbs in a centralised state and saw no need for a federal system because they deemed differences between Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes to be the artificial result of Austrian rule. Supilo protested by informing the Yugoslav Committee he had sent a memo to Grey, proposing an independent Croatian state should be established unless Serbia agreed to treat Croats and Slovenes as equal to Serbs. His principal complaint was that the Entente Powers thought of Croatia and other Austro-Hungarian territories as compensation to Serbia for the loss of

The Serbian position was weakened following the loss of Russian support after the

The Serbian position was weakened following the loss of Russian support after the

Relations between Pašić and Trumbić deteriorated throughout 1918. They openly disagreed on several key demands made by Trumbić, including the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary as allied peoples; the recognition of the Yugoslav Committee as the representative of those peoples; and the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes Volunteer Corps (formerly called the First Serbian Volunteer Division) as an allied force drawn from Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary. After Pašić refused to support these positions, the Yugoslav Committee authorised Trumbić to bypass Pašić and directly present the Entente Powers with their demands. The Serbian government denied the Yugoslav Committee had any legitimacy, saying that Serbia alone represented all South Slavs, including those living in Austria-Hungary.

Pašić requested the Entente Powers issue a declaration recognising Serbia had the right to liberate and unify South Slavic territories with Serbia, but this was unsuccessful. Pašić stated that Yugoslavia would be absorbed by Serbia and not the other way around, that Serbia was primarily waging war to liberate Serbs, and that Pašić had created the Yugoslav Committee. He rejected Trumbić's claim that only one third of population of the future union lived in Serbia and that the Corfu Declaration called for two partners, stating the declaration was only for foreign consumption and was no longer valid. The French and British governments declined two Serbian requests for the authority to annex South Slavic Austro-Hungarian lands, and the British foreign secretary

Relations between Pašić and Trumbić deteriorated throughout 1918. They openly disagreed on several key demands made by Trumbić, including the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary as allied peoples; the recognition of the Yugoslav Committee as the representative of those peoples; and the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes Volunteer Corps (formerly called the First Serbian Volunteer Division) as an allied force drawn from Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary. After Pašić refused to support these positions, the Yugoslav Committee authorised Trumbić to bypass Pašić and directly present the Entente Powers with their demands. The Serbian government denied the Yugoslav Committee had any legitimacy, saying that Serbia alone represented all South Slavs, including those living in Austria-Hungary.

Pašić requested the Entente Powers issue a declaration recognising Serbia had the right to liberate and unify South Slavic territories with Serbia, but this was unsuccessful. Pašić stated that Yugoslavia would be absorbed by Serbia and not the other way around, that Serbia was primarily waging war to liberate Serbs, and that Pašić had created the Yugoslav Committee. He rejected Trumbić's claim that only one third of population of the future union lived in Serbia and that the Corfu Declaration called for two partners, stating the declaration was only for foreign consumption and was no longer valid. The French and British governments declined two Serbian requests for the authority to annex South Slavic Austro-Hungarian lands, and the British foreign secretary

The National Council was confronted by civil unrest and, they believed, a coup d'état plot, and requested help from the Serbian Army to quell the violence. At the same time, the council hoped Serbian support would halt the

The National Council was confronted by civil unrest and, they believed, a coup d'état plot, and requested help from the Serbian Army to quell the violence. At the same time, the council hoped Serbian support would halt the

The Yugoslav Committee (, , ) was a

The Yugoslav Committee (, , ) was a World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

-era, unelected, '' ad-hoc'' committee. It largely consisted of émigré Croat

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, Slovene, and Bosnian Serb politicians and political activists whose aim was the detachment of Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

lands inhabited by South Slavs

South Slavs are Slavic people who speak South Slavic languages and inhabit a contiguous region of Southeast Europe comprising the eastern Alps and the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically separated from the West Slavs and East Slavs by Austria, ...

and unification of those lands with the Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Principality was ruled by the Obrenović dynast ...

. The group was formally established in 1915 and last met in 1919, shortly after the breakup of Austria-Hungary and the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () has been its colloq ...

, which was later renamed Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

. The Yugoslav Committee was led by its president, the Croat lawyer Ante Trumbić, and, until 1916, by Croat politician Frano Supilo

Frano Supilo (30 November 1870 – 25 September 1917) was a Croatian politician and journalist. He opposed the Austro-Hungarian domination of Europe prior to World War I. He participated in the debates leading to the formation of Yugoslavia as ...

as its vice president.

The members of the Yugoslav Committee had different positions on topics such as the method of unification, the desired system of government, and the constitution of the proposed union state. The bulk of the committee members espoused various forms of Yugoslavism

Yugoslavism, Yugoslavdom, or Yugoslav nationalism is an ideology supporting the notion that the South Slavs, namely the Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Macedonians (ethnic group), Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes belong to a single ...

– advocating for either a centralised state or a federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

in which lands constituting the new state would preserve a degree of autonomy. The committee was financially supported by donations from the Croatian diaspora, and by the government of the Kingdom of Serbia, led by Nikola Pašić.

Representatives of the Yugoslav Committee and the Serbian government met on the Greek island of Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

in 1917; they discussed the proposed unification of South Slavs and produced the Corfu Declaration, outlining some elements of the future union's constitution. Further meetings took place at the end of the war in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

in 1918. Those discussions resulted in the Geneva Declaration, which described a confederal constitution of the union. The Government of Serbia repudiated the declaration shortly afterwards. The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( / ; ) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (Prečani (Serbs), Prečani) residing in what were the southernmost parts of th ...

, which was formed as Austria-Hungary was breaking up, treated the Yugoslav Committee as its representative in international affairs. The committee soon came under pressure to unify with Serbia and proceeded to do so in a manner that ignored the earlier declarations. It ceased to exist shortly afterwards.

Background

creation of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia was a State (polity), state concept among the South Slavs, South Slavic intelligentsia and later popular masses from the 19th to early 20th centuries that culminated in its realization after the 1918 collapse of Austria-Hungary at th ...

by nearly a century. The concept was first developed in Habsburg Croatia by a group of Croat intellectuals who formed the Illyrian movement in the 19th century. It evolved through many forms and proposals. The Illyrian intellectuals argued that Croatian history is a part of a wider history of the South Slavs, and that Croats, Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

, and potentially Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

and Bulgarians

Bulgarians (, ) are a nation and South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and its neighbouring region, who share a common Bulgarian ancestry, culture, history and language. They form the majority of the population in Bulgaria, ...

were parts of a single "Illyrian" nation, choosing the name as a neutral term. The movement began as a cultural one, promoting Croatian national identity and integration of all Croatian provinces within the Austrian Empire, usually in reference to the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

kingdoms of Croatia, Slavonia

Slavonia (; ) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria County, Istria, one of the four Regions of Croatia, historical regions of Croatia. Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with f ...

, and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

, and a part or all of Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Ottoman Empire era of rule in Bosnia (first as a ''sanjak'', then as an ''eyalet'') and Herzegovina (also as a ''sanjak'', then ''eyalet'') lasted from 1463/1482 to 1908.

Ottoman conquest

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia and Herzegovin ...

. A wider aim was to gather all South Slavs or ''Jugo-Slaveni'' for short, in a commonwealth within or outside the Empire. The movement's two directions became known as Croatianism and Yugoslavism

Yugoslavism, Yugoslavdom, or Yugoslav nationalism is an ideology supporting the notion that the South Slavs, namely the Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Macedonians (ethnic group), Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes belong to a single ...

respectively, meant to counter Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people, and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In l ...

and Magyarisation.

Fearing the (drive to the east), the Illyrians believed Germanisation and Magyarisation could only be resisted through unity with other Slavs, especially the Serbs. They advocated for the unification of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia as the Triune Kingdom. The concept was expanded to encompass other South Slavs in Austria or Austria-Hungary after the Compromise of 1867, before aspiring to join other South Slavic polities in a federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

or confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

. The proposed consolidation of variously defined Croatian or South Slavic lands led to proposals for trialism in Austria-Hungary, accommodating a South-Slavic polity with a rank equal to the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

.

After the neighbouring Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Principality was ruled by the Obrenović dynast ...

achieved independence through the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, the Yugoslav idea became irrelevant in that country. Before the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

in 1912, Serbia was mono-ethnic and Serbian nationalists sought to include those they considered to be Serbs into the state. It portrayed the work of bishops Josip Juraj Strossmayer

Josip Juraj Strossmayer, also Štrosmajer (; ; 4 February 1815 – 8 April 1905) was a Croatian prelate of the Catholic Church, politician and benefactor (law), benefactor. Between 1849 and his death, he served as the Bishop of Đakovo, Bishop ...

and Franjo Rački as a scheme to establish a Greater Croatia. A group of Royal Serbian Army officers known as the Black Hand exerted pressure to expand Serbia; they carried out a May 1903 coup that brought the Karađorđević dynasty to power and then organised nationalist actions in the "unredeemed Serbian provinces", specified as Bosnia, Herzegovina, Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, an Old Serbia

Old Serbia () is a Serbian historiographical term that is used to describe the territory that according to the dominant school of Serbian historiography in the late 19th century formed the core of the Serbian Empire in 1346–71.

The term does ...

– meaning Kosovo

Kosovo, officially the Republic of Kosovo, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe with International recognition of Kosovo, partial diplomatic recognition. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, Montenegro to the west, Serbia to the ...

– Macedonia, Central Croatia, Slavonia

Slavonia (; ) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria County, Istria, one of the four Regions of Croatia, historical regions of Croatia. Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with f ...

, Syrmia

Syrmia (Ekavian sh-Latn-Cyrl, Srem, Срем, separator=" / " or Ijekavian sh-Latn-Cyrl, Srijem, Сријем, label=none, separator=" / ") is a region of the southern Pannonian Plain, which lies between the Danube and Sava rivers. It is div ...

, Vojvodina

Vojvodina ( ; sr-Cyrl, Војводина, ), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, is an Autonomous administrative division, autonomous province that occupies the northernmost part of Serbia, located in Central Europe. It lies withi ...

, and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

. This echoed Garašanin's 1844 ''Načertanije

The term Greater Serbia or Great Serbia () describes the Serbian nationalist and irredentist ideology of the creation of a Serb state which would incorporate all regions of traditional significance to Serbs, a South Slavic ethnic group, includi ...

'', a treatise that anticipated the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, and which called for the establishment of Greater Serbia to pre-empt Russian or Austrian expansion into the Balkans by unifying all Serbs into a single state.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, Croat, Serb, and Slovene national programmes adopted Yugoslavism in different, conflicting, or mutually exclusive forms. Yugoslavism became a pivotal idea for the establishment of a South Slavic political union. Most Serbs equated the idea with Greater Serbia or a vehicle to bring all Serbs into a single state. For many Croats and Slovenes, Yugoslavism protected them against Austrian and Hungarian challenges to the preservation of their own national identities and political autonomy.

Prelude

Florence meeting

Government of the United Kingdom

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

was considering expanding the alliance against the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

, which at that time consisted of the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. The UK intended to persuade Hungary to secede from Austria-Hungary and to persuade the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

to abandon its neutrality so both countries could join the alliance of the UK, France, and Russia that was known as the Entente Powers. Pašić discovered the UK was considering guaranteeing Hungarian access to the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

through the Port of Rijeka and overland access to Rijeka over Croatian soil, and resolving the Adriatic Question satisfactorily for Italy. Pašić thought these developments, coupled with a potential UK– Romanian alliance, would threaten Serbia and jeopardise the Serbian objective of gaining access to the Adriatic.

In response, Pašić directed two Bosnian Serb members of the Austro-Hungarian Diet of Bosnia

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

, Nikola Stojanović and Dušan Vasiljević, to contact the émigré Croatian politicians and lawyers Ante Trumbić and Julije Gazzari, in order to resist the pro-Hungarian British proposals and to create a Slavic alternative. Pašić proposed the establishment of a body that would cooperate with the Government of Serbia on the unification of South Slavs in a state that would be created through the expansion of Serbia. The policy of expansion was to be set and controlled entirely by Serbia, and the proposed body would carry out propaganda activities on its behalf. The four men met in Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Italy, on 22 November 1914. In January 1915, Frano Supilo

Frano Supilo (30 November 1870 – 25 September 1917) was a Croatian politician and journalist. He opposed the Austro-Hungarian domination of Europe prior to World War I. He participated in the debates leading to the formation of Yugoslavia as ...

, who was once a leading figure in the Croat-Serb Coalition, the ruling political party of the Austro-Hungarian realm of Croatia-Slavonia, met with British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey and Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

, providing them with the manifesto of the nascent Yugoslav Committee and discussing the benefits of South Slavic unification. The manifesto was co-written by Supilo and British political activist and historian Robert Seton-Watson.

Niš Declaration

The Serbian leadership considered World War I to be an opportunity for territorial expansion beyond the Serb-inhabited areas of the

The Serbian leadership considered World War I to be an opportunity for territorial expansion beyond the Serb-inhabited areas of the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. A committee that was tasked with determining the country's war aims produced a program to establish a single South-Slavic state through the addition of Croatia-Slavonia, the Slovene Lands, Vojvodina

Vojvodina ( ; sr-Cyrl, Војводина, ), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, is an Autonomous administrative division, autonomous province that occupies the northernmost part of Serbia, located in Central Europe. It lies withi ...

, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, and Dalmatia. Pašić thought the process should be implemented through the addition of new territories to Serbia. On 7 December, Serbia announced its war aims in the Niš Declaration. The declaration called on South Slavs to struggle to liberate and unify "unliberated brothers", "three tribes of one people" – referring to Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. This formulation was adopted instead of an explicit goal of territorial expansion as a way to attract support from South Slavs living in Austria-Hungary. The Serbian government wanted to appeal to fellow South Slavs because it feared little material support would be delivered from its Entente Powers allies as it became clear the war would not be short. Serbia assumed a central role in the state-building of the future South Slavic polity, with support from the major Entente Powers.

Supilo initially assumed the Niš Declaration meant Serbia was fully supportive of his ideas on the method of unification. He was convinced otherwise by Russian foreign minister Sergey Sazonov, who informed Supilo that Russia only supported the creation of Greater Serbia. As a result, Supilo and Trumbić did not trust Pašić, and considered him a proponent of Serbian hegemony. Despite the mistrust, Supilo and Trumbić wanted to work with Pašić to further the aim of South-Slavic unification. Pašić offered to work with them towards the establishment of a Serbo-Croat state in which Croats would be given some concessions, an offer they declined. Trumbić was convinced the Serbian leadership thought of unification as a means to conquer neighbouring territories for Serbian gain.

Trumbić and Supilo found another reason to distrust Pašić when Pašić dispatched envoys to address Sazonov's opposition to the addition of Roman Catholic South Slavs to the proposed South Slavic union. The envoys wrote a memorandum claiming Croats only inhabit the north of Central Croatia, and that the regions of Slavonia, Krbava

Krbava (; ) is a historical region located in Mountainous Croatia and a former Catholic bishopric (1185–1460), precursor of the diocese of Modruš and present Latin titular see.

It can be considered either located east of Lika, or indeed as ...

, Lika

Lika () is a traditional region of Croatia proper, roughly bound by the Velebit mountain from the southwest and the Plješevica mountain from the northeast. On the north-west end Lika is bounded by Ogulin-Plaški basin, and on the south-east by t ...

, Bačka

Bačka ( sr-Cyrl, Бачка, ) or Bácska (), is a geographical and historical area within the Pannonian Plain bordered by the river Danube to the west and south, and by the river Tisza to the east. It is divided between Serbia and Hungary. ...

, and Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

should be added to Serbia, as well as the previously claimed Dalmatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Trumbić and Supilo became convinced that because of the Government of Serbia's expansionist policy, the proposed unification would be perceived within Croatian-inhabited areas of Austria-Hungary as a Serbian conquest rather than as a liberation. They decided to proceed with caution, gather political support abroad, and to refrain from the establishment of a Yugoslav Committee until Italy's entry into the war became certain.

Treaty of London

The Entente Powers ultimately concluded an alliance with Italy by offering it large areas of Austria-Hungary that were inhabited by South Slavs, mostly Croats and Slovenes, along the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea. The offer was formalised as the 1915 Treaty of London, and caused Trumbić and Supilo to reconsider their criticism of Serbian policies. This was because they saw potential Serbian war success against Austria-Hungary as the only realistic safeguard against Italian expansion into the Slovene-and-Croat-inhabited lands. Supilo was convinced Croatia would be partitioned between Italy, Serbia, and Hungary if the Treaty of London was to be implemented.

The matter became closely related to the Entente's simultaneous efforts to obtain an alliance with Bulgaria, or at least to secure its neutrality, in return for territorial gains against Serbia. As compensation, Serbia was promised territories that were within Austria-Hungary at the time: Bosnia and Herzegovina and an outlet to the Adriatic Sea in Dalmatia. Regardless of the promised compensation, Pašić was reluctant to accede to all of the Bulgarian territorial demands, especially before Serbia had secured the new territories. Supilo obtained British support for plebiscites in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Dalmatia so the populace of those territories would decide on their own fate rather than Britain supplying guarantees of westward territorial expansion to Serbia. Crucially, Serbia received Russian support for its dismissal of the proposed land swap.

The Entente Powers ultimately concluded an alliance with Italy by offering it large areas of Austria-Hungary that were inhabited by South Slavs, mostly Croats and Slovenes, along the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea. The offer was formalised as the 1915 Treaty of London, and caused Trumbić and Supilo to reconsider their criticism of Serbian policies. This was because they saw potential Serbian war success against Austria-Hungary as the only realistic safeguard against Italian expansion into the Slovene-and-Croat-inhabited lands. Supilo was convinced Croatia would be partitioned between Italy, Serbia, and Hungary if the Treaty of London was to be implemented.

The matter became closely related to the Entente's simultaneous efforts to obtain an alliance with Bulgaria, or at least to secure its neutrality, in return for territorial gains against Serbia. As compensation, Serbia was promised territories that were within Austria-Hungary at the time: Bosnia and Herzegovina and an outlet to the Adriatic Sea in Dalmatia. Regardless of the promised compensation, Pašić was reluctant to accede to all of the Bulgarian territorial demands, especially before Serbia had secured the new territories. Supilo obtained British support for plebiscites in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Dalmatia so the populace of those territories would decide on their own fate rather than Britain supplying guarantees of westward territorial expansion to Serbia. Crucially, Serbia received Russian support for its dismissal of the proposed land swap.

Establishment

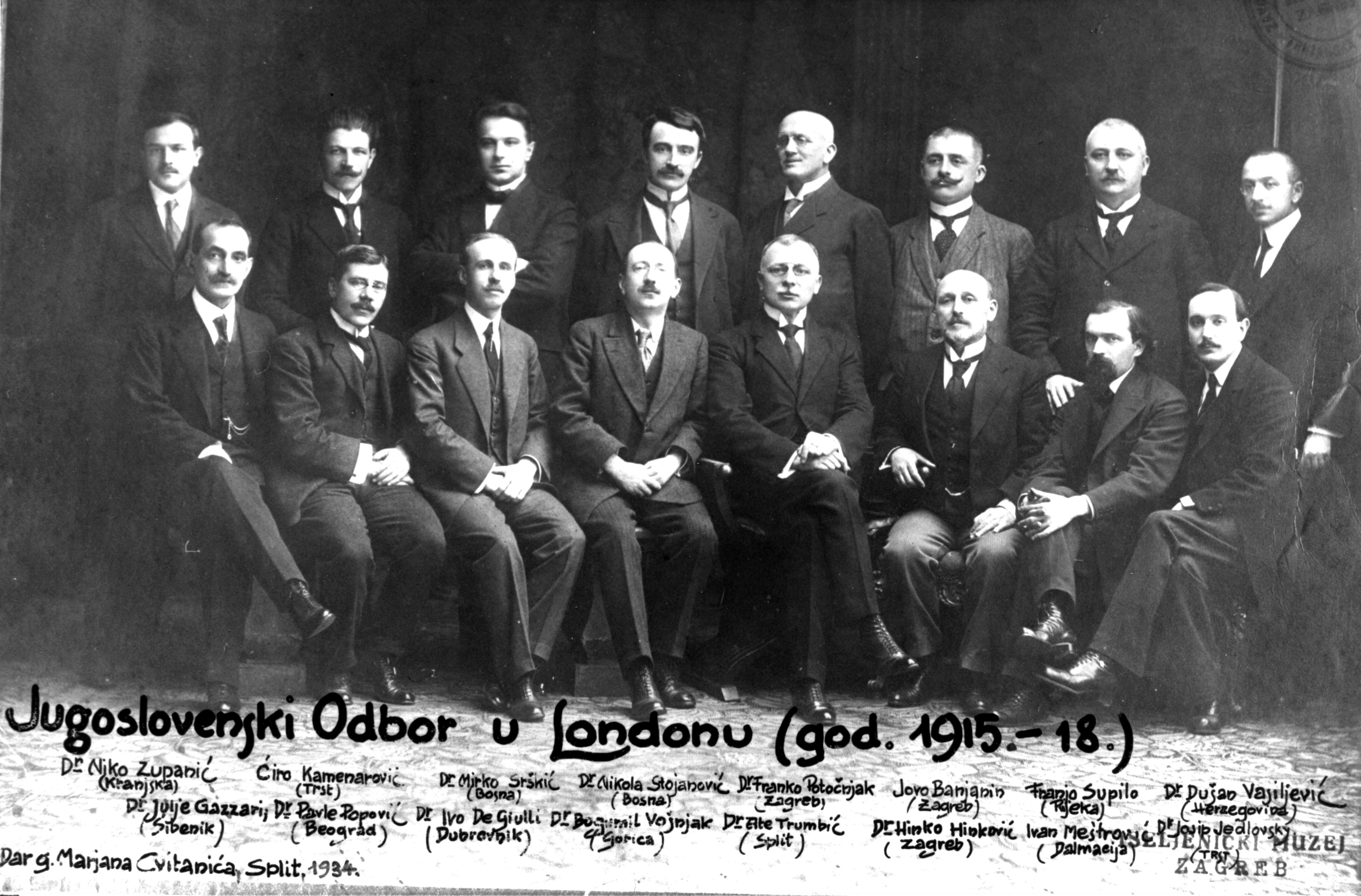

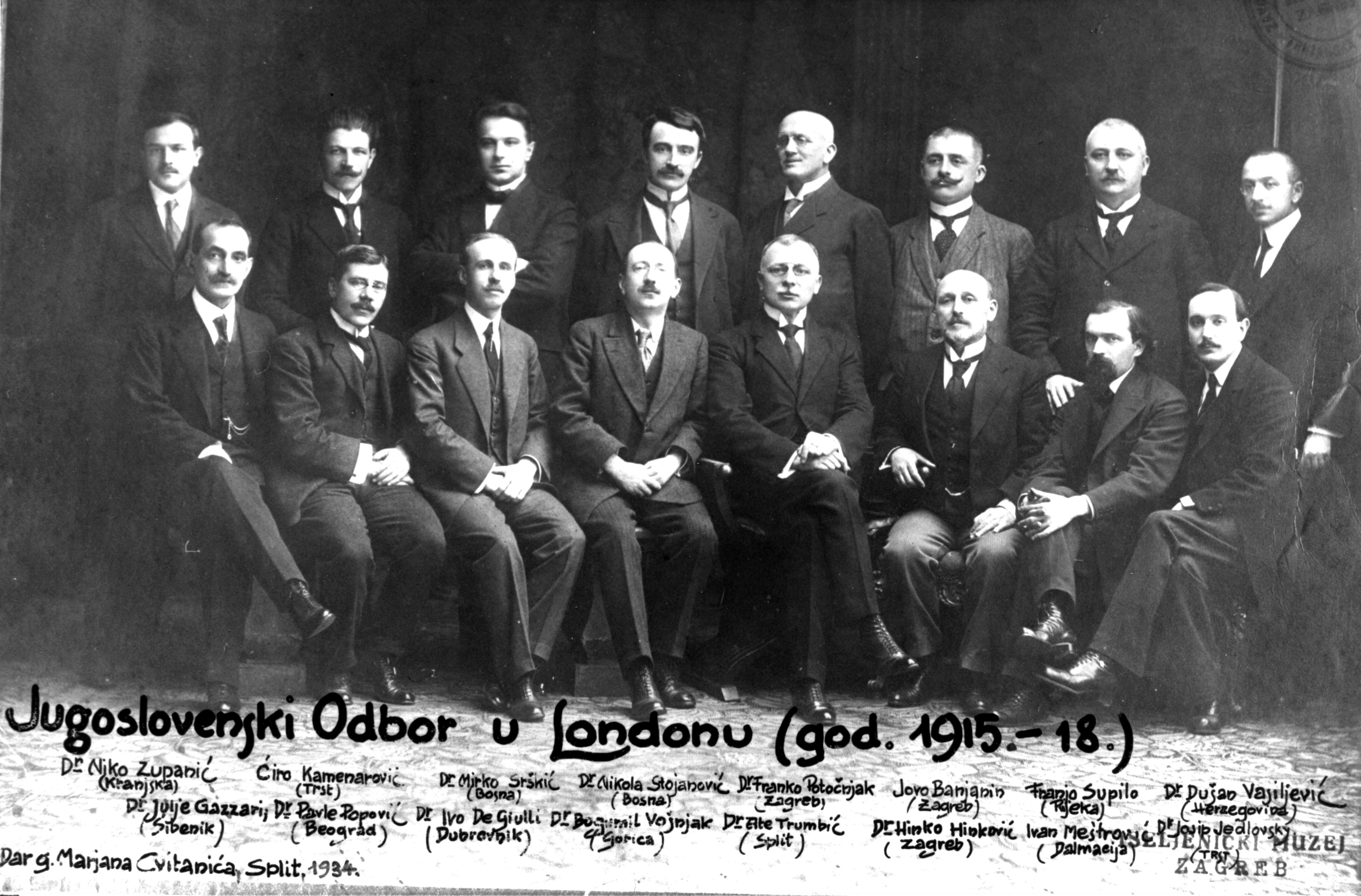

The Yugoslav Committee was formally founded in the Hôtel Madison, Paris, on 30 April 1915, a few days after signing of the London Agreement ensuring Italy's entry into the World War I. The committee designated London as its seat. The committee was an unelected, '' ad-hoc'' group of anti-Habsburg politicians and activists who had fled Austria-Hungary when World War I broke out. The committee's work was largely funded by members of the Croatian diaspora, including Gazzari's brother and the Croatian-Chilean industrialist Remigio. A portion of the costs were covered by the Government of Serbia. Trumbić became the Yugoslav Committee president and Supilo its vice-president. The committee also included Croatian Sabor members sculptor Ivan Meštrović, Hinko Hinković, Jovan Banjanin, and Franko Potočnjak; Diet of Istria member Dinko Trinajstić;Diet of Bosnia

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

members Stojanović and Vasiljević; Imperial Council member ; writer Milan Marjanović; literary historian Pavle Popović; ethnologist Niko Županič; jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyzes and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal education in law (a law degree) and often a Lawyer, legal prac ...

Bogumil Vošnjak

Bogumil Vošnjak, also known as Bogomil Vošnjak (9 September 1882 – 18 June 1955), was a Slovenes, Slovene and Yugoslavia, Yugoslav jurist, politician, diplomat, author, and Legal history, legal historian. He often wrote under the pseudonym Il ...

; Miće Mičić; and Gazzari. Later, the membership also included Milan Srškić, Ante Biankini, Mihajlo Pupin, Lujo Bakotić, Ivan De Giulli, Niko Gršković, Josip Jedlowski, and Josip Mandić. Prominent non-member supporters included and Josip Marohnić, the latter being the president of the North American Croatian Fraternal Union, which collected money for the Yugoslav Committee. The committee's central London office was led by Hinković and Jedlowski. According to some sources, Jedlowski used the title of secretary of the committee, although it appears the position was an administrative one that conferred no special authority.

Members of the Yugoslav Committee believed the Croatian question could only be resolved through the abolition of Austria-Hungary and Croatia's unification with Serbia. Trumbić and Supilo were proponents of a political unification of South Slavs within a single nation-state through the realisation of Yugoslavist ideas. They believed the South Slavs were one people who were entitled to a national homeland through the principle of self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

and advocated for unification based on equality. He advocated for the establishment of a federal state within which Slovene Lands, Croatia (consisting of pre-war Croatia-Slavonia and Dalmatia), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia (expanded to include Vojvodina), and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

would become the five constituent elements. Croat members of the Yugoslav Committee, except Hinković, thought the federal units would ensure preservation of the historical, legal, and cultural traditions of the individual parts of the new state. Supilo proposed the new country would be named Yugoslavia to avoid imposing the name of Serbia onto areas of the new country outside of the pre-war Serbian boundaries. He also suggested Croatia should be given some protection against future Serbian dominance and that Zagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

might be the city most suited to becoming the new country's capital. The Yugoslav Committee believed unification should be the result of an agreement between itself and the Government of Serbia.

The Yugoslav Committee attracted support in the UK, especially that of Seton-Watson, journalist and historian Wickham Steed, and archaeologist Arthur Evans

Sir Arthur John Evans (8 July 1851 – 11 July 1941) was a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age.

The first excavations at the Minoan palace of Knossos on the List of islands of Greece, Gree ...

. The Entente Powers did not initially consider a breakup of Austria-Hungary as a war aim and did not support the work of the committee, whose activities aimed to undermine the territorial integrity of Austria-Hungary. The Yugoslav Committee worked to be recognised by the Entente Powers as the legal representative of South Slavs living in Austria-Hungary, but Pašić consistently prevented any formal recognition. A further point of friction between Supilo and Trumbić on one side and Pašić on the other was the Serbian ambassador's demand to the UK to ask the Yugoslav Committee to omit any mention of Dalmatia as a part of Croatia since time immemorial

Time immemorial () is a phrase meaning time extending beyond the reach of memory, record, or tradition, indefinitely ancient, "ancient beyond memory or record". The phrase is used in legally significant contexts as well as in common parlance.

...

, because it might jeopardise Serbian territorial claims. Supilo and Trumbić were surprised but they complied, believing Croatia would be otherwise left defenceless against Italian territorial claims.

Supilo's resignation

Supilo thought the Yugoslav Committee had to confront Italian and Hungarian attempts to encroach on lands inhabited by South Slavs and the Greater Serbian expansionist designs pursued by Pašić. While most of the committee agreed with Supilo, they did not want to openly confront Serbia until the South Slavic lands were safe from Italian and Hungarian threats. Following the Serbian military defeat in the 1915 Serbian campaign, Supilo, Gazzari, and Trinajstić concluded the Serb members of the Yugoslav Committee believed the proposed unification should primarily encompass ethnic Serbs in a centralised state and saw no need for a federal system because they deemed differences between Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes to be the artificial result of Austrian rule. Supilo protested by informing the Yugoslav Committee he had sent a memo to Grey, proposing an independent Croatian state should be established unless Serbia agreed to treat Croats and Slovenes as equal to Serbs. His principal complaint was that the Entente Powers thought of Croatia and other Austro-Hungarian territories as compensation to Serbia for the loss of

Supilo thought the Yugoslav Committee had to confront Italian and Hungarian attempts to encroach on lands inhabited by South Slavs and the Greater Serbian expansionist designs pursued by Pašić. While most of the committee agreed with Supilo, they did not want to openly confront Serbia until the South Slavic lands were safe from Italian and Hungarian threats. Following the Serbian military defeat in the 1915 Serbian campaign, Supilo, Gazzari, and Trinajstić concluded the Serb members of the Yugoslav Committee believed the proposed unification should primarily encompass ethnic Serbs in a centralised state and saw no need for a federal system because they deemed differences between Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes to be the artificial result of Austrian rule. Supilo protested by informing the Yugoslav Committee he had sent a memo to Grey, proposing an independent Croatian state should be established unless Serbia agreed to treat Croats and Slovenes as equal to Serbs. His principal complaint was that the Entente Powers thought of Croatia and other Austro-Hungarian territories as compensation to Serbia for the loss of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and concessions in Banat instead of treating the populations of these areas as equal partners. Serb and Slovene members of the committee accused Supilo and his allies of separatism and favouring Croatian interests over Slovene ones.

Trumbić believed unification should be pursued at all costs providing Austria-Hungary was destroyed. In March 1916, Trumbić dismissed Supilo's idea of establishing a Croatian Committee, fearing it would lead to conflict with the Serbian government and weaken the Croatians' position against Italy. In early May 1916, Pašić declared Serbian recognition of Italian dominance in the Adriatic, causing Gazzari, Trinajstić, and Meštrović to ask for a meeting of the committee. In the meeting, Vasiljević and Stojanović again attacked Supilo for his opposition to the policy of the Serbian government. Supilo left the Yugoslav Committee on 5 June 1916. Supilo, believing the piecemeal approach being taken was wrong and that problems must be immediately dealt with in the open, abandoned integral Yugoslavism and unsuccessfully urged Croat members of the Yugoslav Committee to resign and join him in pursuit of an independent Croatia because Serbia had prioritised uniting ethnic Serbs. He hoped to obtain Italian support for the idea, because Italy was displeased with the prospect of the unification of South Slavs close to its borders, and thereby pressure Pašić and the Serbs into giving into his demands.

Relations between the Yugoslav Committee and Serbia did not improve after Supilo's departure. A new contentious issue was the designation of the South Slavic volunteer units established in Odesa

Odesa, also spelled Odessa, is the third most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern ...

. These consisted of prisoners of war who had been captured from Austria-Hungary by Russia and now wanted to fight against the Austro-Hungarians on the side of Slavic independence. While the Yugoslav Committee wanted the force to be called Yugoslav, Pašić successfully arranged through Serbian diplomatic mission in Russia to have the unit named the First Serbian Volunteer Division, which was commanded by officers of the Royal Serbian Army who were sent to Russia for the task. While the committee hoped the force would help promote a common Yugoslav identity, Yugoslavism was actively suppressed by the officers, on instructions given by Pašić. As a result, 12,735 of 33,000 volunteers left the force in protest at its specifically Serbian identification, and recruitment of volunteers significantly slowed.

Corfu Declaration

The Serbian position was weakened following the loss of Russian support after the

The Serbian position was weakened following the loss of Russian support after the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

and President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

's refusal to honour secret agreements that had promised territorial rewards. At the same time, the Entente Powers were still looking for ways to achieve a separate peace with Austria-Hungary and isolate the German Empire in the war. South Slavic deputies on the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Council in Vienna presented the May Declaration, proposing the introduction of trialism in Austria-Hungary, allowing the South Slavs to unite in a single polity within the monarchy. France and the UK appeared to support the efforts of new Austro-Hungarian emperor Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

to restructure the empire and seek peace. This presented a problem for the Serbian government, which was exiled on the Greek island of Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

since their military defeat, and increased the risk of a trialist solution for the Habsburg South Slavs if the separate peace treaty materialised, preventing the fulfilment of expansionist Serbian war objectives.

Pašić felt he had to come to an agreement with the Yugoslav Committee to strengthen the Serbian position with the Entente Powers while countering Italian interests in the Balkans. Trumbić and Pašić met on Corfu. At the conference, the Yugoslav Committee was represented by Trumbić, Hinković, Vošnjak, Vasiljević, Trinajstić, and Potočnjak. Trumbić received no information on the conference agenda, so the committee members were unprepared and had to individually negotiate with Pašić. Trumbić prioritised assurances Croatia would not be left within Austria-Hungary and that Italy would not occupy Dalmatia. He also opposed complete centralisation of the proposed union state. The meeting resulted in the Corfu Declaration, a manifesto in which the disparate groups declared a common objective; the unification of South Slavs in a constitutional, democratic, and parliamentary monarchy that would be headed by the Serbian ruling Karađorđević dynasty. Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav Committee's preferred name for the unified country, was rejected and the bulk of the constitutional matters were left to be decided later because Trumbić felt some agreement was necessary to curb threats of Italian expansion.

Pašić–Trumbić conflict

Relations between Pašić and Trumbić deteriorated throughout 1918. They openly disagreed on several key demands made by Trumbić, including the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary as allied peoples; the recognition of the Yugoslav Committee as the representative of those peoples; and the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes Volunteer Corps (formerly called the First Serbian Volunteer Division) as an allied force drawn from Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary. After Pašić refused to support these positions, the Yugoslav Committee authorised Trumbić to bypass Pašić and directly present the Entente Powers with their demands. The Serbian government denied the Yugoslav Committee had any legitimacy, saying that Serbia alone represented all South Slavs, including those living in Austria-Hungary.

Pašić requested the Entente Powers issue a declaration recognising Serbia had the right to liberate and unify South Slavic territories with Serbia, but this was unsuccessful. Pašić stated that Yugoslavia would be absorbed by Serbia and not the other way around, that Serbia was primarily waging war to liberate Serbs, and that Pašić had created the Yugoslav Committee. He rejected Trumbić's claim that only one third of population of the future union lived in Serbia and that the Corfu Declaration called for two partners, stating the declaration was only for foreign consumption and was no longer valid. The French and British governments declined two Serbian requests for the authority to annex South Slavic Austro-Hungarian lands, and the British foreign secretary

Relations between Pašić and Trumbić deteriorated throughout 1918. They openly disagreed on several key demands made by Trumbić, including the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary as allied peoples; the recognition of the Yugoslav Committee as the representative of those peoples; and the recognition of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes Volunteer Corps (formerly called the First Serbian Volunteer Division) as an allied force drawn from Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes living in Austria-Hungary. After Pašić refused to support these positions, the Yugoslav Committee authorised Trumbić to bypass Pašić and directly present the Entente Powers with their demands. The Serbian government denied the Yugoslav Committee had any legitimacy, saying that Serbia alone represented all South Slavs, including those living in Austria-Hungary.

Pašić requested the Entente Powers issue a declaration recognising Serbia had the right to liberate and unify South Slavic territories with Serbia, but this was unsuccessful. Pašić stated that Yugoslavia would be absorbed by Serbia and not the other way around, that Serbia was primarily waging war to liberate Serbs, and that Pašić had created the Yugoslav Committee. He rejected Trumbić's claim that only one third of population of the future union lived in Serbia and that the Corfu Declaration called for two partners, stating the declaration was only for foreign consumption and was no longer valid. The French and British governments declined two Serbian requests for the authority to annex South Slavic Austro-Hungarian lands, and the British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

upheld the Corfu Declaration as an agreement of partners, demanding Pašić align his views with those of the Yugoslav Committee. However, in line with Serbia's wishes, the Entente Powers decided against recognition of the Yugoslav Committee as an allied body, informing the committee it would have to come to an agreement with Pašić.

The potential preservation of Austria-Hungary also caused friction between Trumbić and Pašić. The Entente Powers continued to pursue a separate peace with Austria-Hungary until early 1918, regardless of the Corfu Declaration. In January 1918, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

confirmed his support for the survival of Austria-Hungary. In his Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

speech, Wilson agreed, advocating for the autonomy of the peoples of Austria-Hungary. In October, Lloyd George discussed the potential preservation of a reformed Austria-Hungary with Pašić, saying Serbia could annex any areas occupied by the Royal Serbian Army before an armistice. In return, Trumbić asked Wilson to deploy US troops to Croatia-Slavonia to quell the disorder associated with the Green Cadres, suppress Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

, and not to allow Italian or Serbian troops into the territory. He was unsuccessful.

Geneva Declaration

In the process of the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, following the monarchy's military defeat in 1918, theState of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( / ; ) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (Prečani (Serbs), Prečani) residing in what were the southernmost parts of th ...

was proclaimed in the South Slavic-inhabited lands of the former empire. The new state was governed by the Croat-Serb Coalition-dominated National Council, which authorised the Yugoslav Committee to speak on behalf of the Council in international relations. In late October 1918, the Croatian Sabor declared the end of ties with Austria-Hungary and elected the president of the National Council, Slovene politician Anton Korošec, to the new position of President of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.

Trumbić and Pašić met again in November in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, where they were joined by Korošec and representatives of Serbian opposition parties, to discuss unification. At the conference, Pašić was isolated and ultimately compelled to recognise the National Council as an equal partner to the Serbian government. Trumbić obtained agreement from the other conference participants on the establishment of a common government, in which the National Council and the Government of Serbia would appoint an equal number of ministers to govern a common confederal state. Pašić consented after receiving a message from the President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is the supreme magistracy of the country, the po ...

Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

stating he wished Pašić to come to an agreement with the representatives of the National Council. In return, the National Council and the Yugoslav Committee agreed to a speedy unification, and signed the Geneva Declaration.

A week later, prompted by Pašić, the Serbian government renounced the declaration, saying it limited Serbian sovereignty to its pre-war borders. The Vice President of the National Council, Croatian Serb politician Svetozar Pribićević

Svetozar Pribićević ( sr-Cyrl, Светозар Прибићевић}, ; 26 October 1875 – 15 September 1936) was a Croatian Serb politician in Austria-Hungary and later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He was one of the main proponents of Yugoslavi ...

, supported the repudiation of the Geneva Agreement and swayed the National Council against the position negotiated by Trumbić. Pribićević persuaded the Council members to proceed with unification and accept that the details of the new arrangements would be decided afterwards.

Aftermath

The National Council was confronted by civil unrest and, they believed, a coup d'état plot, and requested help from the Serbian Army to quell the violence. At the same time, the council hoped Serbian support would halt the

The National Council was confronted by civil unrest and, they believed, a coup d'état plot, and requested help from the Serbian Army to quell the violence. At the same time, the council hoped Serbian support would halt the Italian Army

The Italian Army ( []) is the Army, land force branch of the Italian Armed Forces. The army's history dates back to the Italian unification in the 1850s and 1860s. The army fought in colonial engagements in China and Italo-Turkish War, Libya. It ...

's advance from the west, where it had seized Rijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

and was approaching Ljubljana

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Ljubljana

, official_name =

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = {{multiple image

, border = infobox

, perrow = 1/2/2/1

, total_widt ...

. Having no legal means to stop the Italian advance because the Entente Powers had authorised it, nor having sufficient armed forces to stop it, the National Council feared the Italian presence on the eastern shores of the Adriatic would become permanent. The National Council dispatched a delegation to Prince Regent Alexander to arrange an urgent unification with Serbia in a federation. The delegation ignored the instructions it had been given when it addressed the Prince Regent, omitting to secure specific terms for the unification agreement. The Prince Regent accepted the offer on behalf of Peter I of Serbia

Peter I (; – 16 August 1921) was King of Serbia from 15 June 1903 to 1 December 1918. On 1 December 1918, he became King of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and he held that title until his death three years later. Since he was the king ...

and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () has been its colloq ...

, which was subsequently renamed Yugoslavia, was established with no agreement on the nature of the new political union. Mate Drinković, a member of the delegation, informed Trumbić in a letter that unification had been proclaimed, saying any other agreement would have been impossible to obtain.

In early 1919, Trumbić appointed Trinajstić as his replacement at the head of the Yugoslav Committee. The newly appointed Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, Stojan Protić, instructed the Yugoslav Committee to dissolve. On 12 February, Trinajstić convened a meeting, with Trumbić attending; the majority of the committee members decided not to dissolve the body despite Protić's instructions. Nevertheless, the Yugoslav Committee ceased to exist in March 1919.

Czech historian Milada Paulová wrote a book examining the relationship between the Yugoslav Committee and the Serbian government, and its translation was published in 1925. According to Paulová, the committee had to fight for an equal position, while Pašić's actions were guided by Serbian nationalism. Paulová's work had an impact on Yugoslav historiography, especially Slovene and Croatian, and contributed to the interwar

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

debate on the levels of Yugoslavism espoused by the Yugoslav Committee and the Pašić government. In Communist Yugoslavia, the work of the Yugoslav Committee was re-examined from late 1950s, and the results exhibited the first post-war disagreements between Croatian and Serbian historiographies. At the 1961 congress of the union of historians in Ljubljana, Franjo Tuđman

Franjo Tuđman (14 May 1922 – 10 December 1999) was a Croatian politician and historian who became the first president of Croatia, from 1990 until his death in 1999. He served following the Independence of Croatia, country's independe ...

argued the Serbian government had aspired to hegemony and criticised fellow historian Jovan Marjanović, who had claimed otherwise. In 1965, the Zagreb-based Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts published a book emphasising the Yugoslav Committee's contribution to the creation of Yugoslavia.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Authority control Yugoslav unification Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1910s in Yugoslavia Yugoslavism Organizations established in 1915 1910s in politics