Young Turk Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908; ) was a constitutionalist revolution in the

The event that triggered the revolution was a meeting in the Baltic port of Reval between

The event that triggered the revolution was a meeting in the Baltic port of Reval between

24 July 1908 started the Ottoman Empire's Second Constitution Era. There after, a number of decrees are issued, which defined freedom of speech, press and organizations, the dismantlement of intelligence agencies, and a general amnesty to political prisoners. Importantly, the CUP did not overthrow the government and nominally committed itself to democratic ideals and constitutionalism. Between the revolution and the 31 March Incident, the CUP's emerged victorious in a power struggle between the palace (Abdul Hamid II) and the liberated

24 July 1908 started the Ottoman Empire's Second Constitution Era. There after, a number of decrees are issued, which defined freedom of speech, press and organizations, the dismantlement of intelligence agencies, and a general amnesty to political prisoners. Importantly, the CUP did not overthrow the government and nominally committed itself to democratic ideals and constitutionalism. Between the revolution and the 31 March Incident, the CUP's emerged victorious in a power struggle between the palace (Abdul Hamid II) and the liberated  While the Young Turk Revolution had promised organizational improvement, once instituted, the government at first proved itself rather disorganized and ineffectual. Although these working-class citizens had little knowledge of how to control a government, they imposed their ideas on the Ottoman Empire. The CUP had Said Pasha removed from the premiership in less than two weeks for Kâmil Pasha. His quest to revive the Sublime Porte of the

While the Young Turk Revolution had promised organizational improvement, once instituted, the government at first proved itself rather disorganized and ineffectual. Although these working-class citizens had little knowledge of how to control a government, they imposed their ideas on the Ottoman Empire. The CUP had Said Pasha removed from the premiership in less than two weeks for Kâmil Pasha. His quest to revive the Sublime Porte of the

These developments caused the gradual creation of a new governing elite. No longer was power exercised by a small governing elite surrounding the Sultan, the Sublime Porte's independence was restored and a new young clique of bureaucrats and officers gradually took control of politics for the CUP. The parliament confirmed through popular sovereignty both old elites as well as new ones. In 1909 a purge in the army demoted many "Old Turks" while elevating "Young Turk" officers.

The post-revolution CUP undertook a consolidation of itself in order to define its ideology. Those intellectual Unionists that spent years in exile, such as Ahmed Rıza, would be sidelined in favor of the new professional organizers, Mehmed Talât, Doctor Nazım, and Bahaeddin Şakir. The organization's home being Rumeli, delegations were sent to local chapters in Asia and Tripolitania to more firmly attach them to the organizations new headquarters in

These developments caused the gradual creation of a new governing elite. No longer was power exercised by a small governing elite surrounding the Sultan, the Sublime Porte's independence was restored and a new young clique of bureaucrats and officers gradually took control of politics for the CUP. The parliament confirmed through popular sovereignty both old elites as well as new ones. In 1909 a purge in the army demoted many "Old Turks" while elevating "Young Turk" officers.

The post-revolution CUP undertook a consolidation of itself in order to define its ideology. Those intellectual Unionists that spent years in exile, such as Ahmed Rıza, would be sidelined in favor of the new professional organizers, Mehmed Talât, Doctor Nazım, and Bahaeddin Şakir. The organization's home being Rumeli, delegations were sent to local chapters in Asia and Tripolitania to more firmly attach them to the organizations new headquarters in

Proclamation of the Young Turks, 1908

* {{Authority control Rebellions in Turkey Protests in Turkey 1908 in the Ottoman Empire Young Turks 20th-century revolutions

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

, an organization of the Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

to restore the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, recall the parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, and schedule an election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

. Thus began the Second Constitutional Era

The Second Constitutional Era (; ) was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 retraction of the constitution, after the dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies, during the ...

which lasted from 1908–1912 and also the Turkish Revolution, an era of political instability and social change which lasted for more than four decades.

The revolution took place in Ottoman Rumeli in the context of the Macedonian Struggle and the increasing instability of the Hamidian regime. It began with CUP member Ahmed Niyazi's flight into the Albanian highlands. He was soon joined by İsmail Enver, Eyub Sabri, and other Unionist officers. They networked with local Albanians and utilized their connections within the Salonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

based Third Army to instigate a large revolt. A string of assassinations by Unionist '' Fedai'' also contributed to Abdul Hamid's capitulation. Though the constitutional regime established after the revolution eventually succumbed to Unionist dictatorship by 1913, the Ottoman sultanate ceased to be the base of power in Turkey after 1908.

Immediately after the revolution, Bulgaria declared independence from the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary's annexation of nominal Ottoman territory sparked the Bosnian Crisis

The Bosnian Crisis, also known as the Annexation Crisis (, ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Aneksiona kriza, Анексиона криза) or the First Balkan Crisis, erupted on 5 October 1908 when Austria-Hungary announced the annexation of Bosnia and Herzeg ...

.

After an attempted monarchist uprising known as the 31 March incident in favor of Abdul Hamid the following year, he was deposed and his half-brother Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd (; or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) was the penultimate List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1909 to 1918. Mehmed V reigned as a Constitutional monarchy, constitutional monarch. He had ...

ascended the throne.

Background

SultanAbdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

was brought to the throne in August 1876 after a series of palace coups by constitutionalist ministers overthrew first his uncle Abdul Aziz, and then his half-brother Murad V. Under duress, he promulgated a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

and held elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

for a parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. However, with the unsuccessful war with Russia which ended in 1878, he suspended enforcement of the constitution and prorogued parliament. After further consolidating his rule he governed as an absolutist monarch for the next three decades. This left a very small group of individuals able to partake in politics in the Ottoman Empire.

Countering the conservative politics of Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

's reign was the amount of social reform that occurred during this time period. The development of educational institutions in the Ottoman Empire also established the background for political opposition. Abdul Hamid's political circle was close-knit and ever-changing.

Rise of the opposition

The origins of the revolution lie within the Young Turk movement, an opposition movement which wished to see Abdul Hamid II's authoritarianism regime dismantled. Being imperialists, they believed Abdul Hamid was an illegitimate sultan for giving away territories in the Berlin Treaty and for not being confrontational enough to the Great Powers. In addition to a return torule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

instead of royal arbitrary rule, they believed that a constitution would negate any motivation for non-Muslim subjects to join nationalist separatist organizations, and therefore negate any justification by the Great Powers to intervene in the Empire. Most of the Young Turks were exiled intelligentsia, however by 1906–1908 many officers and bureaucrats in the Balkans were inducted into the Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

, the preeminent Young Turk organization.

While the Young Turks were in consensus that some reform was necessary for Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, . ) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the Unity of the Peoples, , needed to keep religion-based ...

, the idea of national unity among the ethnic groups of the Ottoman Empire, they disagreed how far reform should go. The anti-Hamidians in the Ottoman Empire that joined the CUP were conservative liberal, imperialist, technocratists. To what extent they could have achieved praxis was dubious, as Ahmet Rıza, the exiled CUP leader, initially denounced revolution. Some Young Turks wished for a federation of nations under an Ottoman monarch, as exemplified in Prince Sabahaddin's movement, though after his failed coup attempt in 1903 his faction was discredited.

Causes

Economic issues

By the 20th century, the Hamidian system seemed bankrupt. Crop failures caused a famine in 1905, and wage hikes could not keep up with inflation. This led tocivil unrest

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, civil strife, or turmoil, are situations when law enforcement and security forces struggle to maintain public order or tranquility.

Causes

Any number of things may cause civil di ...

in Eastern Anatolia, which the CUP and the Dashnak Committee took advantage of. In December 1907 the government put down the Erzurum Revolt. Constitutionalist revolutions occurred in neighbors of the Ottoman Empire, in Russia in 1905, and in Persia the next year. In 1908, workers began to strike in the capital, which kept the authorities on edge. There were also rumors that the Sultan was in poor health on the eve of the revolution.

Situation in Ottoman Macedonia

Starting in the 1890s, chronic intercommunal violence took hold of Ottoman Macedonia in what came known as the Macedonian struggle, as well as in Eastern Anatolia. Terrorist attacks by national liberation groups were regular occurrences. In response to the Ilinden Uprising of 1903, the Ottoman Empire capitulated to international pressure to implement reforms in Macedonia, known as the Mürzsteg program, under Great Power supervision, offending Muslims living in Macedonia and especially army officers. In 1905, another intervention by the Great Powers for reform in Macedonia was greeted with dread amongst the Muslim population. Throughout this period, the Ottoman Empire's weak economy and Abdul Hamid's distrust of the military meant the army was in constant pay arrears. The Sultan was weary of having the army train with live ammunition anyway, lest an uprising against the order occurred. This sentiment especially applied to theOttoman navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

; once the third largest fleet in 19th century Europe, it was rotting away locked inside the Golden Horn

The Golden Horn ( or ) is a major urban waterway and the primary inlet of the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey. As a natural estuary that connects with the Bosphorus Strait at the point where the strait meets the Sea of Marmara, the waters of the ...

.

The defense of their empire was a matter of great honor within the Ottoman military, but the terrible conditions of their service deeply affected morale for the worse. ''Mektebli'' officers, graduates of the modern military schools, were bottlenecked for promotion, as senior ''alaylı'' officers didn't trust their loyalties. Those stationed in Macedonia were outraged against the sultan, and believed the only way to save Ottoman presence in the region to join revolutionary secret societies. Many Unionist officers of the Third Army based in Salonika were motivated by the fear of a partition of Ottoman Macedonia. A desire to preserve the state, not destroy it, motivated the revolutionaries.

Preparation for the revolution

Following the 1902 Congress of Ottoman Opposition, Ahmed Rıza's Unionists abandoned political evolution and formed a coalition with the Activists, which were political revolutionaries. With the fall of Prince Sabahaddin, Rıza's coalition was once again the leading Young Turk current. In 1907 a new anti-Hamidian secret society was founded in Salonica known as the Ottoman Freedom Committee, founded by figures which achieved prominence post-revolution: Mehmed Talaat, Bahaeddin Şakir, and Doctor Nazım. Following its merger with the CUP, the former became the Internal Headquarters of the CUP, while Rıza's Paris branch became the External Headquarters of the CUP. In the CUP's December 1907 Congress, Rıza, Sabahaddin, and Khachatur Malumian of the Dashnak Committee pledged to overthrow the regime by all means necessary. In practice, this was a tactile alliance between the CUP and Dashnaks which was unpopular in both camps, and the Dashnaks did not play a significant role in the coming revolution. In the lead up to the revolution the CUP courted the many ethnic committee of the volatile melting pot that was Macedonia. With the conclusion of theIMRO

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; ; ), was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Founded in 1893 in Salonica, it init ...

's left-wing congress in May–June 1908, the CUP reached a deal for the left's support and neutrality from their right, but the Macedonian-Bulgarian committee's disunity and their late decision also meant no joint operations between the two groups during the revolution. The Unionists did not seriously court the Serbian Chetniks, but did reach out to the Greek bands for support. Using more sticks than carrots, the CUP walked away with a tenuous declaration of neutrality from the Greeks. The most resources were invested in attaining Albanian support. Albanian feudal lords and notables enjoyed CUP patronage. While the Unionists were less successful in recruiting bourgeois nationalists to their cause they did cultivate a relationship with the Bashkimi Society. The CUP always held a close relationship with the non-Muslim groups of the Vlachs

Vlach ( ), also Wallachian and many other variants, is a term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate speakers of Eastern Romance languages living in Southeast Europe—south of the Danube (the Balkan peninsula ...

, their Christianity being an important propaganda asset, and the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

.

According to Ismail Enver the CUP set the date for their revolution to be sometime in August 1908, though a spontaneous one happened before August anyway.

Revolution

Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

of the United Kingdom and Nicholas II of Russia on 9–12 June 1908. While "the Great Game

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations t ...

", had created a rivalry between the two powers, a resolution to their relationship was sought after. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 brought shaky British-Russian relations to the forefront by solidifying boundaries that identified their respective control in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

(eastern border of the Empire) and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

. It was rumored that in this latest meeting another reform package would be imposed on the Ottoman Empire which would formally partition Macedonia.

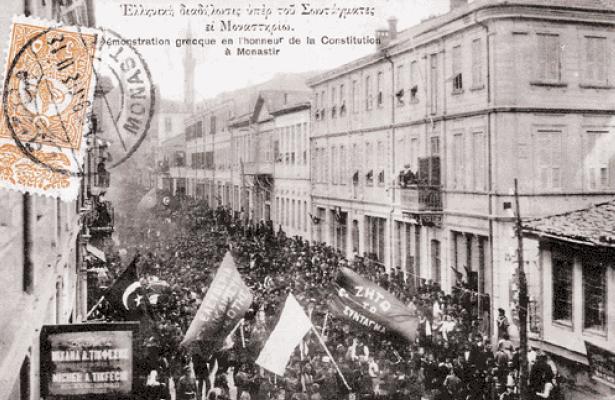

With the newspaper reports of the meeting, the CUP's Monastir (Bitola

Bitola (; ) is a city in the southwestern part of North Macedonia. It is located in the southern part of the Pelagonia valley, surrounded by the Baba, Nidže, and Kajmakčalan mountain ranges, north of the Medžitlija-Níki border crossing ...

) branch decided to act. A memorandum

A memorandum (: memorandums or memoranda; from the Latin ''memorandum'', "(that) which is to be remembered"), also known as a briefing note, is a Writing, written message that is typically used in a professional setting. Commonly abbreviation, ...

was drawn up by Unionists that was distributed to the European consuls which rejected foreign intervention and nationalist activism. They also called for constitutional government and equality amongst Ottoman citizens.

With no action taken by the Great Powers or the government, the revolt began in earnest in the first week of July 1908. On July 3 Major Ahmed Niyazi began the revolution by raiding the Resne ( Resen) garrison cache of money, arms, and ammunition and assembled a force of 160 volunteers to the mountains surrounding the city. From there he visited many villages around the predominantly Muslim Albanian area to recruit for his band and warn of impending European intervention and Christian supremacy in Macedonia. Niyazi would highlight the government's (not the sultan) weakness and corruption as the reason for this crisis, and that a constitutional framework would deliver the systematic reform necessary to negate Western intervention. Niyazi's Muslim Albanian heritage worked to his advantage in this propaganda campaign which also involved settling clan rivalries. When touring Christian Bulgarian and Serbian villages, he highlighted that the constitution would bring about equality between Christians and Muslims, and was able to recruit Bulgarians into his force.

Other Unionists, following Niyazi's example, took to the mountains of Macedonia: Ismail Enver Bey in Tikveş, Eyub Sabri in Ohri (Ohrid

Ohrid ( ) is a city in North Macedonia and is the seat of the Ohrid Municipality. It is the largest city on Lake Ohrid and the eighth-largest city in the country, with the municipality recording a population of over 42,000 inhabitants as of ...

), Bekir Fikri in Grebene (Grevena

Grevena (, ''Grevená'' ; ) is a town and Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Western Macedonia, northern Greece, capital of the Grevena (regional unit), Grevena regional unit. The town's current population is 12,515 citizen ...

), and Salahaddin Bey and Hasan Bey in Kırçova (Kičevo

Kičevo ( ; , sq-definite, Kërçova) is a city in the western part of North Macedonia, located in a valley in the south-eastern slopes of Mount Bistra, between the cities of Ohrid and Gostivar. The capital Skopje is 112 km away. The city ...

). In each post office the rebels came across, they transmitted their demands to the government in Constantinople (Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

): reinstate the constitution and reconvene the parliament otherwise the rebels would march on the capital.On 7 July, Şemsi Pasha arrived at Monastir. Abdul Hamid II dispatched him from Mitroviçe ( Mitrovica) with two battalions to suppress the revolt in Macedonia. An ethnic Albanian, he also recruited a pro-government band of Albanians on the way. He informed the palace of his arrival in the city at the local telegraph station, and as he walked out of the building he was assassinated by a Unionist '' fedai'', Âtıf Kamçıl. His Albanian bodyguards and the pasha's ''aide de camp'', who was his son, were also CUP members. Tatar Osman Pasha, Şemsi's replacement, was captured soon after. On July 22, Monastir fell to the rebels, and Niyazi proclaimed the constitution to the citizens. That day Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

Mehmed Ferid Pasha was sacked for Said Pasha.

Elsewhere, Hayri Pasha, field marshal of the Third Army, was threatened by the committee into a passive cooperation. At this point, the mutiny which originated in the Third Army in Salonica took hold of the Second Army based in Adrianople (Edirne

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

) as well as Anatolian troops sent from Smyrna ( Izmir).

The rapid momentum of the Unionist's organization, intrigues within the military, discontent with Abdul Hamid's autocratic rule, and a desire for the Constitution meant the sultan and his ministers were compelled to capitulate. Over the course of a three day meeting with his Council of Ministers, a unanimous decision was reached to reinstate the constitution. Under pressure of being deposed, on the night of 23–24 July 1908, Abdul Hamid II issued the '' İrade-i Hürriyet'', reinstating the Constitution and calling an election to great jubilation.

Celebrations were held intercommunally, as Muslims and Christians attended celebrations together in both churches and mosques. Parades were held throughout the Empire, with attendants shouting '' Egalité! Liberté! Justice! Fraternité!'' ''Vive la constitution!'' and ''Padişahım çok yaşa!'' (Long live my emperor). Armed bands of Serbian, Bulgarian, and Greek '' chetas'', one time enemies of each other and the government, took part in celebrations before ceremoniously turning in their firearms to the government. Niyazi, Enver, and the other Unionist revolutionaries were celebrated as "heroes of liberty", and Ahmed Rıza, returning from his exile was declared "father of liberty".

Aftermath

Impact on the Second Constitutional Era

Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

. Until the December election, the CUP dominated the empire in what Şükrü Hanioğlu deemed a '' Comité de salut public.''

Following the revolution, many organizations, some of them previously underground, established political parties. The several political currents expressed amongst the Young Turks lead to disagreements on what liberty meant. Among these the CUP and the Liberty Party and later on Freedom and Accord Party, were the major ones. There were smaller parties such as Ottoman Socialist Party and the Democratic Party. On the other end of the spectrum were the ethnic parties which included the People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section), the Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs, the Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party in Palestine (Poale Zion), Al-Fatat, and Armenians organized under the Armenakan, the Hunchaks and the Dashnaks.

The 1908 Ottoman general election took place during November and December 1908. Due to its leading role in the revolution, the CUP won almost every seat in the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

. The large parliamentary group and the then lax laws on party affiliation eventually whittled the delegation into a smaller and more cohesive group of 60 MPs. The Senate of the Ottoman Empire

The Senate of the Ottoman Empire (, or ; ; lit. "Assembly of Notables"; ) was the upper house of the parliament of the Ottoman Empire, the General Assembly. Its members were appointed notables in the Ottoman government who, along with the electe ...

reconvened for the first time in over 30 years on 17 December 1908 with the living members like Hasan Fehmi Pasha from the First Constitutional Era

The First Constitutional Era (; ) of the Ottoman Empire was the period of constitutional monarchy from the promulgation of the Ottoman constitution of 1876 (, , meaning ' Basic Law' or 'Fundamental Law' in Ottoman Turkish), written by members ...

.  While the Young Turk Revolution had promised organizational improvement, once instituted, the government at first proved itself rather disorganized and ineffectual. Although these working-class citizens had little knowledge of how to control a government, they imposed their ideas on the Ottoman Empire. The CUP had Said Pasha removed from the premiership in less than two weeks for Kâmil Pasha. His quest to revive the Sublime Porte of the

While the Young Turk Revolution had promised organizational improvement, once instituted, the government at first proved itself rather disorganized and ineffectual. Although these working-class citizens had little knowledge of how to control a government, they imposed their ideas on the Ottoman Empire. The CUP had Said Pasha removed from the premiership in less than two weeks for Kâmil Pasha. His quest to revive the Sublime Porte of the Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

proved fruitless when CUP soon censored him with a no-confidence vote in parliament, thus he was replaced by Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha who was more in-line with the committee's ways.

Abdul Hamid maintained his throne by conceding its existence as a symbolic position, but in April 1909 attempted to seize power (see 31 March Incident) by stirring populist sentiment throughout the Empire. The Sultan's bid for a return to power gained traction when he promised to restore the caliphate

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

, eliminate secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

policies, and restore the Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

-based legal system. On 13 April 1909, army units revolted, joined by masses of theological students and turbaned clerics shouting, "We want Sharia", and moving to restore the Sultan's absolute power. The CUP once again assembled a force in Macedonia to march on the capital and restored parliamentary rule after crushing the uprising on 24 April 1909. The deposition of Abdul Hamid II

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a Decline and modernizati ...

in favor of Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd (; or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) was the penultimate List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1909 to 1918. Mehmed V reigned as a Constitutional monarchy, constitutional monarch. He had ...

followed, and the palace ceased to be a significant player in Ottoman politics.

New elites

These developments caused the gradual creation of a new governing elite. No longer was power exercised by a small governing elite surrounding the Sultan, the Sublime Porte's independence was restored and a new young clique of bureaucrats and officers gradually took control of politics for the CUP. The parliament confirmed through popular sovereignty both old elites as well as new ones. In 1909 a purge in the army demoted many "Old Turks" while elevating "Young Turk" officers.

The post-revolution CUP undertook a consolidation of itself in order to define its ideology. Those intellectual Unionists that spent years in exile, such as Ahmed Rıza, would be sidelined in favor of the new professional organizers, Mehmed Talât, Doctor Nazım, and Bahaeddin Şakir. The organization's home being Rumeli, delegations were sent to local chapters in Asia and Tripolitania to more firmly attach them to the organizations new headquarters in

These developments caused the gradual creation of a new governing elite. No longer was power exercised by a small governing elite surrounding the Sultan, the Sublime Porte's independence was restored and a new young clique of bureaucrats and officers gradually took control of politics for the CUP. The parliament confirmed through popular sovereignty both old elites as well as new ones. In 1909 a purge in the army demoted many "Old Turks" while elevating "Young Turk" officers.

The post-revolution CUP undertook a consolidation of itself in order to define its ideology. Those intellectual Unionists that spent years in exile, such as Ahmed Rıza, would be sidelined in favor of the new professional organizers, Mehmed Talât, Doctor Nazım, and Bahaeddin Şakir. The organization's home being Rumeli, delegations were sent to local chapters in Asia and Tripolitania to more firmly attach them to the organizations new headquarters in Salonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

. The CUP would dominate Ottoman politics for the next ten years, save for brief interruption from 1912 to 1913. 5 of these years would be a dictatorship established in the aftermath of the 1913 coup and Mahmud Shevket Pasha's assassination, during which they drove the empire to fight alongside Germany during World War I and commit genocide against Ottoman Christians.

The revolution also served as a downfall for the non-Muslim elites which benefited from the Hamidian system. The Dashnaks, previously leading a guerilla resistance in the Eastern Anatolian countryside, became the main representatives of the Armenian community in the Ottoman Empire, replacing the urban centered pre-1908 Armenian '' amira'' class, which had been composed of merchants, artisans, and clerics. The Armenian National Assembly used the moment to oust Patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Roman Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and ...

Malachia Ormanian for Matthew II Izmirlian. This served to elevate younger Armenian nationalists, overthrowing the previous communal domination by pro-imperialist Armenians.

The elite Bulgarian community of Istanbul were similarly displaced by a youthful nationalist-intellectual class involved with IMRO

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; ; ), was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Founded in 1893 in Salonica, it init ...

, as was the Albanian Hamidian elite. Arab and Albanian elites, which were favored under the Hamidian regime, found many privileges lost under the CUP. The revolution continued to destabilize the subservient Sharifate of Mecca

The Sharifate of Mecca () or Emirate of Mecca was a state, ruled by the Sharif of Mecca. The Egyptian encyclopedist al-Qalqashandi described it as a Bedouin state, in that being similar to its neighbor and rival in the north the Sharifat ...

as several claimed the title until November 1908, when the CUP recognized Hussein bin Ali Pasha as Emir. In some communities, such as the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

(cf. Jews in Islamic Europe and North Africa and Jews in Turkey), reformist groups emulating the Young Turks ousted the conservative ruling elite and replaced them with a new reformist one. Social institutions like notable families and houses of worship lost influence to the burgeoning world of party politics. Political clubs, committees, and parties were now the main actors in politics. Though these non-Turkish nationalists cooperated with the Young Turks against the sultan, they would turn on each other during the Second Constitutional Era over the question of Ottomanism, and ultimately autonomy and separatism.

Cultural and international impact

Two European powers took advantage of the chaos by decreasing Ottoman sovereignty in the Balkans.Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, ''de jure'' an Ottoman vassal but ''de facto'' all but formally independent, declared its independence on the 5th of October. The day after, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

officially annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina which used to be de jure Ottoman territory but de facto occupied by Austria-Hungary. The fall of Abdul Hamid II foiled the rapprochement between Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

and the Ottoman Empire which set the stage for their alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or sovereign state, states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an a ...

with Bulgaria and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

in the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

.

Following the revolution a new found faith in Ottomanism was found in the various ''millets''. Violence in Macedonia ceased as rebels turned in their arms and celebrated with citizens. An area from Scutari to Basra was now acquainted with political parties, nationalist clubs, elections, constitutional rights, and civil rights.

The revolution and CUP's work greatly impacted Muslims in other countries. The Persian community in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

founded the Iranian Union and Progress Committee. The leaders of the Young Bukhara movement were deeply influenced by the Young Turk Revolution and saw it as an example to emulate. Indian Muslims

Islam is India's second-largest religion, with 14.2% of the country's population, or approximately 172.2 million people, identifying as adherents of Islam in a 2011 census. India also has the third-largest number of Muslims in the world. ...

imitated the CUP oath administered to recruits of the organization. Discontent in the Greek military saw a secret revolutionary organization explicitly modeled from the CUP which overthrew the government in the Goudi Coup, bringing Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

to power.

In popular culture

The Young Turks

''The Young Turks'' (''TYT'') is an American progressive and left-wing populist sociopolitical news and commentary program live streamed on social media platforms YouTube and Twitch, and additionally selected television channels. ''TYT'' se ...

is a news commentary show named after the historical movement and live streamed since 2002 on social media platforms, such as YouTube

YouTube is an American social media and online video sharing platform owned by Google. YouTube was founded on February 14, 2005, by Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim who were three former employees of PayPal. Headquartered in ...

and Twitch.

In the 2010 alternate history novel ''Behemoth

Behemoth (; , ''bəhēmōṯ'') is a beast from the biblical Book of Job, and is a form of the primeval chaos-monster created by God at the beginning of creation. Metaphorically, the name has come to be used for any extremely large or powerful ...

'' by Scott Westerfeld

Scott David Westerfeld (born May 5, 1963) is an American writer of young adult fiction, best known as the author of the ''Uglies series, Uglies'' and the ''Leviathan (Westerfeld novel), Leviathan'' series.

Early life

Westerfeld was born in Dal ...

, the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 fails, igniting a new revolution at the start of World War I.

Historiography

HistorianRonald Grigor Suny

Ronald Grigor Suny (born September 25, 1940) is an American-Armenian historian and political scientist. Suny is the William H. Sewell Jr. Distinguished University Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Michigan and served as directo ...

states that the revolution had no popular support and was actually "a coup d'état by a small group of military officers and civilian activists in the Balkans".

* Hanioğlu states the revolution a watershed moment in the late Ottoman Emire but it was not a popular constitutional movement.

See also

*Bosnian Crisis

The Bosnian Crisis, also known as the Annexation Crisis (, ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Aneksiona kriza, Анексиона криза) or the First Balkan Crisis, erupted on 5 October 1908 when Austria-Hungary announced the annexation of Bosnia and Herzeg ...

References

Bibliography

* * . * * * * . * * * * * * *Further reading

Proclamation of the Young Turks, 1908

* {{Authority control Rebellions in Turkey Protests in Turkey 1908 in the Ottoman Empire Young Turks 20th-century revolutions

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

July 1908 in Europe

Conflicts in 1908