Yakima Wars on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Yakima War (1855–1858), also referred to as the Plateau War or Yakima Indian War, was a conflict between the

On September 20, 1855,

On September 20, 1855,

On November 3 Maloney ordered a force of 100 men under Lt. William Slaughter to cross the White River and engage Leschi's forces. Attempts to ford the river, however, were stopped by the fire of Indian sharpshooters. One American soldier was killed in a back-and-forth exchange of gunfire. Accounts of Indian fatalities range from one (reported by a Puyallup Indian, Tyee Dick, after the end of the war) to 30 (claimed in Slaughter's official report), though the lower number may be more credible (one veteran of the battle, Daniel Mounts, would later be appointed Indian agent to the Nisqually and heard Tyee Dick's casualty numbers confirmed by Nisqually). At four o'clock, when it was becoming too dark for the Americans to cross the White River, Leschi's men fell back three miles to their camp on the banks of the Green River, jubilant at having successfully prevented the American crossing (Tyee Dick would later describe the battle as ''hi-ue he-he, hi-ue he-he'' - "lots and lots of fun").

The next morning Maloney advanced with 150 men across the White River and attempted to engage Leschi at his camp at the Green River, but poor terrain made the advance untenable and he quickly called off the attack. Another skirmish on November 5 resulted in five American fatalities, but no Indian deaths. Unable to make any headway, Maloney began his withdrawal from the area on November 7, arriving at Fort Steilacoom two days later.

On November 3 Maloney ordered a force of 100 men under Lt. William Slaughter to cross the White River and engage Leschi's forces. Attempts to ford the river, however, were stopped by the fire of Indian sharpshooters. One American soldier was killed in a back-and-forth exchange of gunfire. Accounts of Indian fatalities range from one (reported by a Puyallup Indian, Tyee Dick, after the end of the war) to 30 (claimed in Slaughter's official report), though the lower number may be more credible (one veteran of the battle, Daniel Mounts, would later be appointed Indian agent to the Nisqually and heard Tyee Dick's casualty numbers confirmed by Nisqually). At four o'clock, when it was becoming too dark for the Americans to cross the White River, Leschi's men fell back three miles to their camp on the banks of the Green River, jubilant at having successfully prevented the American crossing (Tyee Dick would later describe the battle as ''hi-ue he-he, hi-ue he-he'' - "lots and lots of fun").

The next morning Maloney advanced with 150 men across the White River and attempted to engage Leschi at his camp at the Green River, but poor terrain made the advance untenable and he quickly called off the attack. Another skirmish on November 5 resulted in five American fatalities, but no Indian deaths. Unable to make any headway, Maloney began his withdrawal from the area on November 7, arriving at Fort Steilacoom two days later.

That evening Kamiakan called a war council where it was decided the Yakama would make a stand in the hills of Union Gap. Rains began advancing on the hills the next morning, his progress slowed by small groups of Yakama employing

That evening Kamiakan called a war council where it was decided the Yakama would make a stand in the hills of Union Gap. Rains began advancing on the hills the next morning, his progress slowed by small groups of Yakama employing

Meanwhile, Leschi, having successfully repelled and evaded the previous American attempts to defeat his forces along the White River, now faced a third wave of attack. As construction on Fort Tilton got underway, Patkanim - brevetted to the rank of captain in the Volunteers - set out at the head of a force of 55 Snoqualmie and Snohomish warriors intent on capturing Leschi. Their mission was triumphantly announced by a headline in Olympia's ''Pioneer and Democrat'' "Pat Kanim in the Field!"

Patkanim tracked Leschi to his camp along the White River, but a planned night raid was aborted after a barking dog alerted sentries. Instead, Patkanim approached within speaking distance of Leschi's camp, announcing to the Nisqually chief, "I will have your head." Early the next morning Patkanim began his assault, the bloody fight reportedly lasting ten hours, ending only after the Snoqualmie ran out of ammunition.

Meanwhile, Leschi, having successfully repelled and evaded the previous American attempts to defeat his forces along the White River, now faced a third wave of attack. As construction on Fort Tilton got underway, Patkanim - brevetted to the rank of captain in the Volunteers - set out at the head of a force of 55 Snoqualmie and Snohomish warriors intent on capturing Leschi. Their mission was triumphantly announced by a headline in Olympia's ''Pioneer and Democrat'' "Pat Kanim in the Field!"

Patkanim tracked Leschi to his camp along the White River, but a planned night raid was aborted after a barking dog alerted sentries. Instead, Patkanim approached within speaking distance of Leschi's camp, announcing to the Nisqually chief, "I will have your head." Early the next morning Patkanim began his assault, the bloody fight reportedly lasting ten hours, ending only after the Snoqualmie ran out of ammunition.

Learning of Lander's detention, Francis A. Chenoweth, the chief justice of the territorial supreme court, left

Learning of Lander's detention, Francis A. Chenoweth, the chief justice of the territorial supreme court, left

Hubert H. Bancroft, ''History Of Washington, Idaho, and Montana, 1845-1889''

San Francisco: The History Company, 1890. Chapter VI: Indian Wars 1855-1856, and V :Indian Wars 1856-1858 * Ray Hoard Glassley: ''Indian Wars of the Pacific Northwest'', Binfords & Mort, Portland, Oregon 1972

"Yakama (Yakima) Indian War begins on October 5, 1855"

HistoryLink.org Essay 5311

"Major Gabriel Rains and 700 soldiers and volunteers skirmish with Yakama warriors under Kamiakin at Union Gap on November 9, 1855"

HistoryLink.org Essay 8124

"Yakama tribesmen slay Indian Subagent Andrew J. Bolon near Toppenish Creek on September 23, 1855"

HistoryLink.org Essay 8118

"Guide to the Yakima War (1856-1858)"

Washington State University Library {{Authority control Conflicts in 1855 Conflicts in 1856 Conflicts in 1857 Conflicts in 1858 1855 in the United States Wars between the United States and Native Americans Native American history of Washington (state) History of Washington (state) Indian wars of the American Old West 1856 in the United States 1857 in the United States 1858 in the United States Yakama

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the Yakama

The Yakama are a Native Americans in the United State, Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in Eastern Washington, eastern Washington (state), Washington state.

Yakama people today are enrolled in the federally rec ...

, a Sahaptian-speaking people of the Northwest Plateau

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

, then part of Washington Territory

The Washington Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

, and the tribal allies of each. It primarily took place in the southern interior of present-day Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

. Isolated battles in western Washington

Western Washington is a region of the United States defined as the area of Washington State west of the Cascade Mountains. This region is home to the state's largest city, Seattle, the state capital, Olympia, and most of the state's residents. ...

and the northern Inland Empire

The Inland Empire (commonly abbreviated as the IE) is a metropolitan area and region inland of and adjacent to coastal Southern California, centering around the cities of San Bernardino and Riverside, and bordering Los Angeles County and Or ...

are sometimes separately referred to as the Puget Sound War

The Puget Sound War was an armed conflict that took place in the Puget Sound area of the state of Washington in 1855–56, between the United States military, local militias and members of the Native American tribes of the Nisqually, Muck ...

and the Coeur d'Alene War

The Coeur d'Alene War of 1858, also known as the Spokane-Coeur d'Alene-Pend d'oreille-Paloos War, was the second phase of the Yakima War, involving a series of encounters between the allied Native American tribes of the Skitswish ("Coeur d'Alen ...

, respectively.

Background

After theWashington Territory

The Washington Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

was formally organized as a U.S. territory in 1853, treaties between the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

government and several Indian tribes in the area resulted in reluctant tribal recognition of U.S. sovereignty over a vast amount of land within the new territory. In return for this recognition, the tribes were entitled to receive half of the fish in the territory in perpetuity, awards of money and provisions, and reserved lands where white settlement would be prohibited.

While territorial governor Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represe ...

had guaranteed the inviolability of Native American territory following tribal accession to the treaties, he lacked the legal authority to enforce it pending ratification of the agreements by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

. Meanwhile, the widely publicized discovery of gold in Yakama territory prompted an influx of unruly prospectors

Prospecting is the first stage of the geological analysis (followed by exploration) of a territory. It is the search for minerals, fossils, precious metals, or mineral specimens. It is also known as fossicking.

Traditionally prospecting rel ...

who traveled, unchecked, across the newly defined tribal lands, to the growing consternation of Indian leaders. In 1855 two of these prospectors were killed by Qualchan

Qualchan (died September 24, 1858) was a 19th-century Yakama chieftain who participated in the Yakama War with his Uncle Kamiakin and other chieftains.

Qualchan was born into the We-ow-icht family, reputed to have come from the stars. His spir ...

, the nephew of Kamiakin, after it was discovered they had raped a Yakama woman.

Outbreak of hostilities

Death of Mosheel’s family

A party of American miners came across two Yakama women, a mother and daughter traveling together with a baby. The miners assaulted and killed both women and the infant. The husband and father of the women, a Yakama man named Mosheel, collected two friends, one of whom was Qualchin, and the men tracked down the miners who had killed Mosheel’s family. They ambushed the murderers in their camp and killed all of them.Death of Andrew Bolon

On September 20, 1855,

On September 20, 1855, Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, Department of the Interior. It is responsible for im ...

agent Andrew Bolon

Andrew Jackson Bolon (c. 1826 – September 25, 1855) was a Bureau of Indian Affairs agent whose 1855 death at the hands of renegade Yakama is considered one of several contributing factors in the outbreak of the Yakima War. Some sources asser ...

, hearing of the death of the prospectors at the hands of Qualchin, departed for the scene on horseback to investigate but was intercepted by the Yakama chief Shumaway, who warned him Qualchin was too dangerous to confront. Heeding Shumaway's warning, Bolon turned back and began the ride home. En route he came upon a group of Yakama traveling south and decided to ride along with them. One of the members of this group was Mosheel, Shumaway's son. After Bolon told Mosheel that the death of the miners was considered a wrongdoing and would be punished by United States army soon as he returned home, Mosheel grew angry. At some point, he decided Bolon should be killed. Though a number of Yakama in the traveling party protested, their objections were overruled by Mosheel, who invoked his regal status. Discussions about Bolon's fate took place over much of the day (Bolon, who did not speak Yakama, was unaware of this debate as it unfolded among his traveling companions).

During a rest stop, as Bolon and the Yakama were eating lunch, Mosheel and at least three other Yakama set upon him with knives. Bolon yelled out in a Chinook dialect, "I did not come to fight you!" before being stabbed in the throat. Bolon's horse was then shot, and his body and personal effects burned.

Battle of Toppenish Creek

When Shumaway heard of Bolon's death he immediately sent an ambassador to inform the U.S. Army garrison atFort Dalles

Fort Dalles was a United States Army outpost located on the Columbia River at the present location of The Dalles, Oregon, in the United States. Built when Oregon was a territory, the post was used mainly for dealing with wars with Native Americ ...

, before calling for the arrest of his own son, Mosheel, who he said should be turned over to the territorial government in order to forestall the American retaliation he felt would likely occur. A Yakama council overruled the chief, however, siding with Shumaway's older brother, Kamiakin, who called for war preparations. Meanwhile, district commander Gabriel Rains

Gabriel James Rains (June 4, 1803 – September 6, 1881) was a career United States Army officer and a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Gabriel James Rains was born in June 1803 in N ...

had received Shumaway's ambassador and, in response to the news of Bolon's death, ordered Major Granville O. Haller to move out with an expeditionary column from Fort Dalles. Haller's force was met and turned back at the edge of Yakama territory by a large group of Yakama warriors. As Haller withdrew, his company was engaged and routed by the Yakama at the Battle of Toppenish Creek

The Battle of Toppenish Creek was the first engagement of the Yakima War in Washington. Fought on October 5, 1855, a company of American soldiers, under Major Granville O. Haller, was attacked by a band of Yakamas, under Chief Kamiakin, and co ...

.

War spreads

The death of Bolon and the United States defeat at Toppenish Creek caused panic across the Washington Territory, provoking fears that an Indian uprising was in progress. The same news emboldened the Yakama and many uncommitted bands rallied to Kamiakin. Rains, who had just 350 federal troops under his immediate command, urgently appealed to Acting GovernorCharles Mason

Charles Mason (25 April 1728Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

where he had traveled to present the treaties to the Senate for ratification) for military aid, writing that

Meanwhile, Oregon Governor George Law Curry

George Law Curry (July 2, 1820 – July 28, 1878) was a predominant American political figure and newspaper publisher in the region that eventually became the state of Oregon. A native of Pennsylvania, he published a newspaper in St. Louis, Miss ...

mobilized a cavalry regiment of 800 men, a portion of which crossed into Washington Territory in early November. Now with more than 700 troops at his disposal, Rains prepared to march on Kamiakin, who had encamped at Union Gap

Union Gap is a city in Yakima County, Washington, United States. The population was 6,568 at the 2020 census. Union Gap has become the retail hub for the entire Yakima Valley as a result of Valley Mall and other thriving businesses being locat ...

with 300 warriors.

Raid on the White River settlements

As Rains was mustering his forces in Pierce County, Leschi, aNisqually

Nisqually, Niskwalli, or Nisqualli may refer to:

People

* Nisqually people, a Coast Salish ethnic group

* Nisqually Indian Tribe of the Nisqually Reservation, federally recognized tribe

** Nisqually Indian Reservation, the tribe's reservation in ...

chief who was half Yakama, had sought to forge an alliance among the Puget Sound tribes to bring war to the doorstep of the territorial government. Starting with just the 31 warriors in his own band, Leschi rallied more than 150 Muckleshoot, Puyallup, and Klickitat, though other tribes rebuffed Leschi's overtures. In response to news of Leschi's growing army, a volunteer troop of 18 dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat wi ...

s, known as Eaton's Rangers, was dispatched to arrest the Nisqually chief.

On October 27, while surveying an area of the White River, ranger James McAllister and farmer Michael Connell were ambushed and killed by Leschi's men. The rest of Eaton's Rangers were besieged inside an abandoned cabin, where they would remain for the next four days before escaping. The next morning Muckleshoot and Klickitat warriors raided three settler cabins along the White River, killing nine men and women. Many settlers had left the area in advance of the raid, having been warned of danger by Chief Kitsap

Kitsap (; ) was a leader of the Suquamish people during the 19th century. Kitsap was the orchestrator of a region-wide coalition that sought to end the constant slave raids perpetrated by the Cowichan. His wealth and prestige allowed him to bu ...

of the neutral Suquamish

The Suquamish () are a Lushootseed-speaking Native American people, located in present-day Washington in the United States. They are a southern Coast Salish people.

Today, most Suquamish people are enrolled in the federally recognized Su ...

. Details of the raid on the White River settlements were told by John King, one of the four survivors, who was seven years old at the time and was – along with two younger siblings spared by the attackers and told to head west. The King children eventually came upon a local Native American known to them as Tom.

Leschi would later express regret for the raid on the White River settlements and post-war accounts given by Nisqually in his band affirmed that the chief had rebuked his commanders who had organized the attack.

Battle of White River

Army Captain Maurice Maloney, in command of a reinforced company of 243 men, had previously been sent east to cross the Naches Pass and enter the Yakama homeland from the rear. Finding the pass blocked with snow he began returning west in the days following the raid on the White River settlements. On November 2, 1855 Leschi's men were spotted by the vanguard of Maloney's returning column, and fell back to the right bank of the White River. On November 3 Maloney ordered a force of 100 men under Lt. William Slaughter to cross the White River and engage Leschi's forces. Attempts to ford the river, however, were stopped by the fire of Indian sharpshooters. One American soldier was killed in a back-and-forth exchange of gunfire. Accounts of Indian fatalities range from one (reported by a Puyallup Indian, Tyee Dick, after the end of the war) to 30 (claimed in Slaughter's official report), though the lower number may be more credible (one veteran of the battle, Daniel Mounts, would later be appointed Indian agent to the Nisqually and heard Tyee Dick's casualty numbers confirmed by Nisqually). At four o'clock, when it was becoming too dark for the Americans to cross the White River, Leschi's men fell back three miles to their camp on the banks of the Green River, jubilant at having successfully prevented the American crossing (Tyee Dick would later describe the battle as ''hi-ue he-he, hi-ue he-he'' - "lots and lots of fun").

The next morning Maloney advanced with 150 men across the White River and attempted to engage Leschi at his camp at the Green River, but poor terrain made the advance untenable and he quickly called off the attack. Another skirmish on November 5 resulted in five American fatalities, but no Indian deaths. Unable to make any headway, Maloney began his withdrawal from the area on November 7, arriving at Fort Steilacoom two days later.

On November 3 Maloney ordered a force of 100 men under Lt. William Slaughter to cross the White River and engage Leschi's forces. Attempts to ford the river, however, were stopped by the fire of Indian sharpshooters. One American soldier was killed in a back-and-forth exchange of gunfire. Accounts of Indian fatalities range from one (reported by a Puyallup Indian, Tyee Dick, after the end of the war) to 30 (claimed in Slaughter's official report), though the lower number may be more credible (one veteran of the battle, Daniel Mounts, would later be appointed Indian agent to the Nisqually and heard Tyee Dick's casualty numbers confirmed by Nisqually). At four o'clock, when it was becoming too dark for the Americans to cross the White River, Leschi's men fell back three miles to their camp on the banks of the Green River, jubilant at having successfully prevented the American crossing (Tyee Dick would later describe the battle as ''hi-ue he-he, hi-ue he-he'' - "lots and lots of fun").

The next morning Maloney advanced with 150 men across the White River and attempted to engage Leschi at his camp at the Green River, but poor terrain made the advance untenable and he quickly called off the attack. Another skirmish on November 5 resulted in five American fatalities, but no Indian deaths. Unable to make any headway, Maloney began his withdrawal from the area on November 7, arriving at Fort Steilacoom two days later.

Battle of Union Gap

One hundred fifty miles to the east, on November 9, Rains closed with Kamiakin nearUnion Gap

Union Gap is a city in Yakima County, Washington, United States. The population was 6,568 at the 2020 census. Union Gap has become the retail hub for the entire Yakima Valley as a result of Valley Mall and other thriving businesses being locat ...

. The Yakama had erected a defensive barrier of stone breastwork which was quickly blown away by American artillery fire. Kamiakan had not expected a force of the size Rains had mustered and the Yakama, anticipating a quick victory of the kind they had recently scored at Toppenish Creek, had brought their families. Kamiakan now ordered the women and children to flee as he and the warriors fought a delaying action. While leading a reconnaissance of the American lines, Kamiakan and a group of fifty mounted warriors encountered an American patrol which gave chase. Kamiakan and his men escaped across the Yakima River; the Americans were unable to keep up and two soldiers drowned before the pursuit was called off.

That evening Kamiakan called a war council where it was decided the Yakama would make a stand in the hills of Union Gap. Rains began advancing on the hills the next morning, his progress slowed by small groups of Yakama employing

That evening Kamiakan called a war council where it was decided the Yakama would make a stand in the hills of Union Gap. Rains began advancing on the hills the next morning, his progress slowed by small groups of Yakama employing hit and run tactics

Hit-and-run tactics are a tactical doctrine of using short surprise attacks, withdrawing before the enemy can respond in force, and constantly maneuvering to avoid full engagement with the enemy. The purpose is not to decisively defeat the ene ...

to delay the American advance against the main Yakama force. At four o'clock in the afternoon Maj. Haller, backed by a howitzer bombardment, led a charge against the Yakama position. Kamiakan's forces scattered into the brush at the mouth of Ahtanum Creek

Ahtanum Creek is a tributary of the Yakima River in the U.S. state of Washington. It starts at the confluence of the Middle and North Forks of Ahtanum Creek near Tampico, flows along the north base of Ahtanum Ridge, ends at the Yakima River near U ...

and the American offensive was called off.

In Kamiakan's camp, plans for a night raid against the American force were drawn up but abandoned. Instead, early the next day, the Yakama continued their defensive retreat, tiring American forces who eventually broke off the engagement. In the last day of fighting the Yakama suffered their only fatality, a warrior killed by U.S. Army Indian Scout Cutmouth John.

Rains continued to Saint Joseph's Mission which had been abandoned, the priests having joined the Yakama in flight. During a search of the grounds, Rains' men discovered a barrel of gunpowder, leading them to erroneously believe the priests had been secretly arming the Yakama. A riot among the soldiers ensued and the mission was burned to the ground. With snow beginning to fall, Rains ordered a withdrawal, and the column returned to Fort Dalles.

Skirmish at Brannan's Prairie

By the end of November, federal troops had returned to the White River area. A detachment of the 4th Infantry Regiment, under Lt. Slaughter, accompanied by militia under Capt. Gilmore Hays, searched the area from which Maloney had previously withdrawn and engaged Nisqually and Klickitat warriors at Biting's Prairie on November 25, 1855, resulting in several casualties but no decisive outcome. The next day an Indian sharpshooter killed two of Slaughter's troops. Finally, on December 3, as Slaughter and his men were camped for the night on Brannan's Prairie, the force was fired upon and Slaughter killed. News of the death of Slaughter greatly demoralized settlers in the principal towns. Slaughter and his wife were a popular young couple among the settlers and the legislature adjourned for a day of mourning.Conflict of command

In late November 1855 Gen.John E. Wool

John Ellis Wool (February 20, 1784 – November 10, 1869) was a US officer in the United States Army during three consecutive American-involved wars: the War of 1812 (1812–1815), the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), and with allegiance to ...

arrived from California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

and assumed control of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

side in the conflict, making his headquarters at Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th-century fur trading post built in the winter of 1824–1825. It was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was ...

. Wool was widely considered pompous and arrogant and had been criticized by some for blaming much of the Western conflicts between Natives and whites on whites. After assessing the situation in Washington, he decided that Rains' approach of chasing bands of Yakama around the territory would lead to an inevitable defeat. Wool planned to wage a static war by using the territorial militia to fortify the major settlements while better-trained and equipped U.S. Army regulars moved in to occupy traditional Indian hunting and fishing grounds, starving the Yakama into surrender.

To Wool's chagrin, however, Oregon Governor Curry decided to launch a preemptive and largely unprovoked attack against the eastern tribes of the Walla Walla, Palouse, Umatilla, and Cayuse who had, up to that point, remained cautiously neutral in the conflict (Curry believed it was only a matter of time before the eastern tribes entered the war and sought to gain a strategic advantage by attacking first). Oregon militia, under Lt. Col. James Kelley, crossed into the Walla Walla Valley in December, skirmishing with the tribes and, eventually, capturing Peopeomoxmox and several other chiefs. The eastern tribes were now firmly involved in the conflict, a state-of-affairs Wool blamed squarely on Curry. In a letter to a friend, Wool commented that

Meanwhile, on December 20, Washington Governor Isaac Stevens had finally made it back to the territory after a perilous journey that involved a final, mad dash across the hostile Walla Walla Valley. Dissatisfied with Wool's plan to wait until spring before resuming military operations, and having learned of the raid on the White River settlement, Stevens convened the Washington Legislature where he declared "the war shall be prosecuted until the last hostile Indian is exterminated. Stevens was further perturbed at the lack of a military escort afforded him during his dangerous passage through Walla Walla and went on to denounce Wool for "the criminal neglect of my safety." Oregon Governor Curry joined his Washington counterpart in demanding Wool's dismissal. (The matter came to a head in the fall of 1856 and Wool was reassigned by the Army to command of the Eastern Department.)

1856

Battle of Seattle

In late January 1856, Stevens arrived in Seattle aboard the '' USCS Active'' to reassure citizens of the town. Stevens confidently declared that, "I believe thatNew York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

and San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

will as soon be attacked by the Indians as the town of Seattle." Even as Stevens was speaking, however, a 6,000-man tribal army was moving on the unsuspecting settlement. As the governor's ship was sailing from the harbor - carrying Stevens back to Olympia - members of some of the Puget Sound's neutral tribes began streaming into Seattle requesting sanctuary from a large Yakama war party that had just crossed Lake Washington

Lake Washington () is a large freshwater lake adjacent to the city of Seattle, Washington, United States.

It is the largest lake in King County, Washington, King County and the second largest natural lake in the state of Washington (state), Was ...

. The threat was confirmed with the arrival of Princess Angeline

Princess Angeline ( – May 31, 1896), also known in Lushootseed as Kikisoblu, Kick-is-om-lo, or Wewick, was the eldest daughter of Chief Seattle.

Biography

She was born around 1820 to Chief Seattle in what is now Rainier Beach in Seattle, Wash ...

who brought news from her father, Chief Seattle

Seattle ( – June 7, 1866; , ; usually styled as Chief Seattle) was a leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish peoples. A leading figure among his people, he pursued a path of accommodation to white settlers, forming a personal relationship wi ...

, that an attack was imminent. Doc Maynard

David Swinson "Doc" Maynard (March 22, 1808March 13, 1873) was an American doctor and businessman. He was one of Seattle's primary founders. Maynard was Seattle's first doctor, merchant prince, second lawyer, Sub-Indian Agent, Justice of the Peace ...

began the evacuation of women and children from the neutral Duwamish, by boat, to the west side of Puget Sound while a group of citizen volunteers, led by the marine detachment

A Marine Detachment, or MarDet, was a unit of United States Marines permanently embarked on large warships including cruisers, battleships, and aircraft carriers, typically consisting of anywhere 35 and 85 men. They were a regular component of a s ...

of the nearby-anchored , started construction on a blockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

.

On the evening of January 24, 1856, two scouts from the massing tribal forces, dressed in disguise and talking their way past American sentries, covertly entered Seattle on a reconnaissance mission (some believe one of these scouts may have been Leschi himself).

Just after sunrise on January 25, 1856, American lookouts spotted a large group of Indians approaching the settlement under cover of trees. The began firing into the woods, prompting townspeople to evacuate to the blockhouse. Tribal forces - by some accounts composed of Yakama

The Yakama are a Native Americans in the United State, Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in Eastern Washington, eastern Washington (state), Washington state.

Yakama people today are enrolled in the federally rec ...

, Walla Walla, Klickitat and Puyallup

Puyallup may refer to:

* Puyallup people, a Coast Salish people

* Puyallup Tribe of Indians, a federally-recognized tribe

* Puyallup, Washington, a city

** Puyallup High School

** Puyallup School District

** Puyallup station, a Sounder commuter ...

- returned fire with small arms and began a fast advance on the settlement. Faced with unrelenting fire from ''Decaturs guns, however, the attackers were forced to withdraw and regroup, after which a decision was made to abandon the assault. Two Americans were killed in the fighting and 28 Natives lost their lives.

Snoqualmie operations

To block the passes across the Cascade Mountains and prevent further Yakama movements againstwestern Washington

Western Washington is a region of the United States defined as the area of Washington State west of the Cascade Mountains. This region is home to the state's largest city, Seattle, the state capital, Olympia, and most of the state's residents. ...

, a small redoubt was established near Snoqualmie Falls

Snoqualmie Falls is a waterfall in the northwest United States, located east of Seattle on the Snoqualmie River between Snoqualmie and Fall City, Washington. It is one of Washington's most popular scenic attractions and is known internationall ...

by Tokul Creek in February 1856. Fort Tilton became operational in March 1856, consisting of a blockhouse and several storehouses. The fort was manned by a small contingent of Volunteers supported by a 100-man force of Snoqualmie warriors, fulfillment of an agreement made by the powerful Snoqualmie chief Patkanim with the government the previous November.

Meanwhile, Leschi, having successfully repelled and evaded the previous American attempts to defeat his forces along the White River, now faced a third wave of attack. As construction on Fort Tilton got underway, Patkanim - brevetted to the rank of captain in the Volunteers - set out at the head of a force of 55 Snoqualmie and Snohomish warriors intent on capturing Leschi. Their mission was triumphantly announced by a headline in Olympia's ''Pioneer and Democrat'' "Pat Kanim in the Field!"

Patkanim tracked Leschi to his camp along the White River, but a planned night raid was aborted after a barking dog alerted sentries. Instead, Patkanim approached within speaking distance of Leschi's camp, announcing to the Nisqually chief, "I will have your head." Early the next morning Patkanim began his assault, the bloody fight reportedly lasting ten hours, ending only after the Snoqualmie ran out of ammunition.

Meanwhile, Leschi, having successfully repelled and evaded the previous American attempts to defeat his forces along the White River, now faced a third wave of attack. As construction on Fort Tilton got underway, Patkanim - brevetted to the rank of captain in the Volunteers - set out at the head of a force of 55 Snoqualmie and Snohomish warriors intent on capturing Leschi. Their mission was triumphantly announced by a headline in Olympia's ''Pioneer and Democrat'' "Pat Kanim in the Field!"

Patkanim tracked Leschi to his camp along the White River, but a planned night raid was aborted after a barking dog alerted sentries. Instead, Patkanim approached within speaking distance of Leschi's camp, announcing to the Nisqually chief, "I will have your head." Early the next morning Patkanim began his assault, the bloody fight reportedly lasting ten hours, ending only after the Snoqualmie ran out of ammunition. Edmond Meany

Edmond Stephen Meany (December 28, 1862 – April 22, 1935) was a professor of botany and history at the University of Washington (UW). He was an alumnus of the university, having graduated as the valedictorian of his class in 1885 when it was th ...

would later write that Patkanim returned with "gruesome evidence of his battles in the form of heads taken from the bodies of slain hostile Indians." Leschi's, however, was not among them.

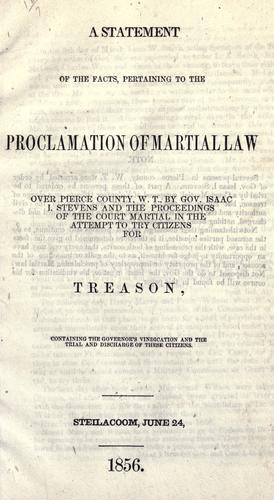

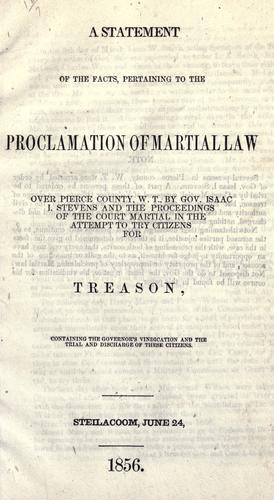

Martial law declared

By spring of 1856, Stevens began to suspect that some settlers in Pierce County, who had married into area tribes, were secretly conspiring with their Native American in-laws against the territorial government. Stevens' distrust of the Pierce County settlers may have been heightened by the strong Whig Party sentiment in the county and opposition to Democratic policies. Stevens ordered the suspect farmers arrested and held at Camp Montgomery. When Judge Edward Lander ordered their release, Stevens declaredmartial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

in Pierce and Thurston counties. On May 12 Lander ruled that Stevens was in contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the co ...

. Marshals sent to Olympia to detain the governor were ejected from the capitol and Stevens ordered Judge Lander's arrest by militia.

Learning of Lander's detention, Francis A. Chenoweth, the chief justice of the territorial supreme court, left

Learning of Lander's detention, Francis A. Chenoweth, the chief justice of the territorial supreme court, left Whidbey Island

Whidbey Island (historical spellings Whidby, Whitbey, or Whitby) is the largest of the islands composing Island County, Washington, Island County, Washington (state), Washington, in the United States, and the largest island in Washington stat ...

- where he was recuperating from illness - and traveled by canoe

A canoe is a lightweight, narrow watercraft, water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using paddles.

In British English, the term ' ...

to Pierce County. Arriving in Steilacoom, Chenoweth reconvened the court and prepared to again issue writs of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

ordering the release of the settlers. Learning of Chenoweth's arrival in Pierce County, Stevens sent a company of militia to stop the chief justice, but the troops were met by the Pierce County Sheriff whom Chenoweth had ordered to raise a posse

Posse is a shortened form of posse comitatus, a group of people summoned to assist law enforcement. The term is also used colloquially to mean a group of friends or associates.

Posse may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Posse'' (1975 ...

to defend the court. The impasse was finally resolved after Stevens agreed to back down and release the farmers.

Stevens subsequently pardoned himself of contempt, but the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

called for his removal over the incident and he was censured by the Secretary of State of the United States

A secretary, administrative assistant, executive assistant, personal secretary, or other similar titles is an individual whose work consists of supporting management, including executives, using a variety of project management, program evalu ...

who wrote to him that "... your conduct, in that respect, does not therefore meet with the favorable regard of the President."

The Cascades Massacre

The Cascades Massacre on March 26, 1856 was the name given to an attack by a coalition of tribes against white soldiers and settlers in theCascades Rapids

The Cascades Rapids (sometimes called Cascade Falls or Cascades of the Columbia) were an area of rapids along North America's Columbia River, between the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon. Through a stretch approximately wide, the river dr ...

. The native attackers included warriors from the Yakama, Klickitat, and ''Cascades tribes'' (today identified as belonging to Wasco tribes: ''Cascades Indians / Watlala'' or ''Hood River Wasco''). Fourteen settlers and three US soldiers died in the attack, the most losses for US citizens during the Yakima War. The United States sent reinforcements the following day to defend against further attacks. The Yakama people fled, but nine Cascades Indians who surrendered without a fight, including Chenoweth, Chief of the Hood River Band, were improperly charged and executed for treason.

Puget Sound War

The U.S. Army arrived in the region in the summer of 1856. That AugustRobert S. Garnett

Robert Selden Garnett (December 16, 1819 – July 13, 1861) was a career military officer, serving in the United States Army until the American Civil War, when he became a Confederate States Army Brigadier General (CSA), brigadier general. He w ...

supervised the construction of Fort Simcoe

Fort Simcoe was a United States Army fort erected in south-central Washington Territory to house troops sent to keep watch over local Indian tribes. The site and remaining buildings are preserved as Fort Simcoe Historical State Park, located w ...

as a military post. Initially the conflict was limited to the Yakama, but eventually the Walla Walla and Cayuse were drawn into the war, and carried out a number of raids and battles against the American invaders.

Coeur d'Alene War

The last phase of the conflict, sometimes referred to as theCoeur d'Alene War

The Coeur d'Alene War of 1858, also known as the Spokane-Coeur d'Alene-Pend d'oreille-Paloos War, was the second phase of the Yakima War, involving a series of encounters between the allied Native American tribes of the Skitswish ("Coeur d'Alen ...

, occurred in 1858. General Newman S. Clarke commanded the Department of the Pacific

The Department of the Pacific or Pacific Department was a major command ( Department) of the United States Army from 1853 to 1858. It replaced the Pacific Division, and was itself replaced by the Department of California and the Department of O ...

and sent a force under Col. George Wright to deal with the recent fighting. At the Battle of Four Lakes

The Battle of Four Lakes was a battle during the Coeur d'Alene War of 1858 in the Washington Territory (now the states of Washington and Idaho) in the United States. The Coeur d'Alene War was part of the Yakima War, which began in 1855. The bat ...

near Spokane, Washington

Spokane ( ) is the most populous city in eastern Washington and the county seat of Spokane County, Washington, United States. It lies along the Spokane River, adjacent to the Selkirk Mountains, and west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, south o ...

in September 1858, Wright inflicted a decisive defeat on the Native Americans. He called a council of all the local Native Americans at Latah Creek (southwest of Spokane). On September 23 he imposed a peace treaty, under which most of the tribes were to go to reservations.

Aftermath

As the war wound to a close, Kamiakin fled north toBritish Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

. Leschi was twice tried for murder by the territorial government (his first trial resulted in a hung jury

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. A hung jury may result in the case being tried again.

Thi ...

), convicted the second time, and then hanged outside Fort Steilacoom, the U.S. Army having refused to allow his execution to occur on Army property as military commanders considered him a lawful combatant

Combatant is the legal status of a person entitled to directly participate in hostilities during an armed conflict, and may be intentionally targeted by an adverse party for their participation in the armed conflict. Combatants are not afforded i ...

. (In 2004 a Historical Court, convened by the State of Washington, conceded the Army's opinion and posthumously acquitted Leschi of murder.)

U.S. Army Indian scouts tracked and captured Andrew Bolon's murderers who were subsequently hanged.

Snoqualmie warriors were sent to hunt-down remnant hostile forces, with the territorial government agreeing to pay a bounty on scalps, however, the practice was quickly terminated by orders of the territorial auditor after questions arose as to whether the Snoqualmie were actually engaging remnant hostiles, or executing their own slaves.

The Yakama people were forced onto a reservation south of the present city of Yakima

Yakima ( or ) is a city in and the county seat of Yakima County, Washington, United States, and the state's 11th most populous city. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total population of 96,968 and a metropolitan population of 256,728. The ...

.

See also

*Bannock War

The Bannock War of 1878 was an armed conflict between the U.S. military and Bannock and Paiute warriors in Idaho and northeastern Oregon from June to August 1878. The Bannock totaled about 600 to 800 in 1870 because of other Shoshone peoples ...

*Cayuse War

The Cayuse War (1847–1855) was an armed conflict between the Cayuse people of the Northwestern United States and settlers, backed by the U.S. government. The conflict was triggered by the Whitman massacre of 1847, where the Cayuse attacked a ...

*Fort Dalles

Fort Dalles was a United States Army outpost located on the Columbia River at the present location of The Dalles, Oregon, in the United States. Built when Oregon was a territory, the post was used mainly for dealing with wars with Native Americ ...

*Fraser Canyon War

The Fraser Canyon War, also known as the Canyon War or the Fraser River War, was an incident between white miners and the indigenous Nlaka'pamux people in the newly declared Colony of British Columbia, which later became part of Canada, in 1858 ...

*Nez Perce War

The Nez Perce War was an armed conflict in 1877 in the Western United States that pitted several bands of the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans and their allies, a small band of the ''Palouse'' tribe led by Red Echo (''Hahtalekin'') and ...

*Okanagan Trail

The Okanagan Trail was an inland route to the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush from the Lower Columbia region of the Washington and Oregon Territories in 1858–1859. The route was essentially the same as that used by the Hudson's Bay Company fur brig ...

*Rogue River War

The Rogue River Wars were an armed conflict in 1855–1856 between the U.S. Army, local militias and volunteers, and the Native American tribes commonly grouped under the designation of Rogue River Indians, in the Rogue Valley area of what t ...

*Spokane-Coeur d'Alene-Paloos War

The Coeur d'Alene War of 1858, also known as the Spokane-Coeur d'Alene-Pend d'oreille-Paloos War, was the second phase of the Yakima War, involving a series of encounters between the allied Native American tribes of the Skitswish ("Coeur d'Alen ...

References

Literature

Hubert H. Bancroft, ''History Of Washington, Idaho, and Montana, 1845-1889''

San Francisco: The History Company, 1890. Chapter VI: Indian Wars 1855-1856, and V :Indian Wars 1856-1858 * Ray Hoard Glassley: ''Indian Wars of the Pacific Northwest'', Binfords & Mort, Portland, Oregon 1972

External links

"Yakama (Yakima) Indian War begins on October 5, 1855"

HistoryLink.org Essay 5311

"Major Gabriel Rains and 700 soldiers and volunteers skirmish with Yakama warriors under Kamiakin at Union Gap on November 9, 1855"

HistoryLink.org Essay 8124

"Yakama tribesmen slay Indian Subagent Andrew J. Bolon near Toppenish Creek on September 23, 1855"

HistoryLink.org Essay 8118

"Guide to the Yakima War (1856-1858)"

Washington State University Library {{Authority control Conflicts in 1855 Conflicts in 1856 Conflicts in 1857 Conflicts in 1858 1855 in the United States Wars between the United States and Native Americans Native American history of Washington (state) History of Washington (state) Indian wars of the American Old West 1856 in the United States 1857 in the United States 1858 in the United States Yakama