William Kelly Harrison Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Kelly Harrison Jr. (September 7, 1895 – May 25, 1987) was a highly decorated officer in the

Harrison graduated with a

Harrison graduated with a

The 30th Infantry Division was ordered for rest and refit to the rear by the end of November 1944 and transferred to the

The 30th Infantry Division was ordered for rest and refit to the rear by the end of November 1944 and transferred to the

Harrison was finally ordered to South Korea in December 1951 and appointed deputy commander of the

Harrison was finally ordered to South Korea in December 1951 and appointed deputy commander of the  Following the promotion, Harrison was appointed the deputy commanding general and chief of staff of the Far East Command under Clark and retained his assignment as the senior member in the truce talks team. He participated in the regular meetings with North Korean delegation led by General

Following the promotion, Harrison was appointed the deputy commanding general and chief of staff of the Far East Command under Clark and retained his assignment as the senior member in the truce talks team. He participated in the regular meetings with North Korean delegation led by General

Harrison retired from the Army on February 28, 1957, after almost 40 years of service and settled in

Harrison retired from the Army on February 28, 1957, after almost 40 years of service and settled in

Arlington National Cemetery recordDallas Theological Seminary archive"Professional Excellence for the Christian Officer"

{{DEFAULTSORT:Harrison, William Kelly Jr. 1895 births 1987 deaths Military personnel from Washington, D.C. United States Military Academy alumni United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army War College alumni United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army Command and General Staff College faculty United States Army personnel of the Korean War Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Silver Star Recipients of the Legion of Merit Officers of the Legion of Honour American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Companions of the Order of the Bath Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Officers of the Order of Orange-Nassau Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Panmunjom United States Army Cavalry Branch personnel United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

with the rank of Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

. A graduate of the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

, he rose through the ranks to brigadier general during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and distinguished himself in combat several times, while serving as the assistant division commander of the 30th Infantry Division during the Normandy Campaign

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the N ...

and the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive or Unternehmen Die Wacht am Rhein, Wacht am Rhein, was the last major German Offensive (military), offensive Military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western ...

. Harrison was decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest decoration of the United States military for bravery in combat, for his actions during Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was an offensive launched by the First United States Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take advantage of the dis ...

.

Following the War, Harrison remained in the Army and after several stateside assignments, he was ordered to the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

, where he served as head of the United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the South Korea, Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first attempt at collective security by the U ...

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

delegation in the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

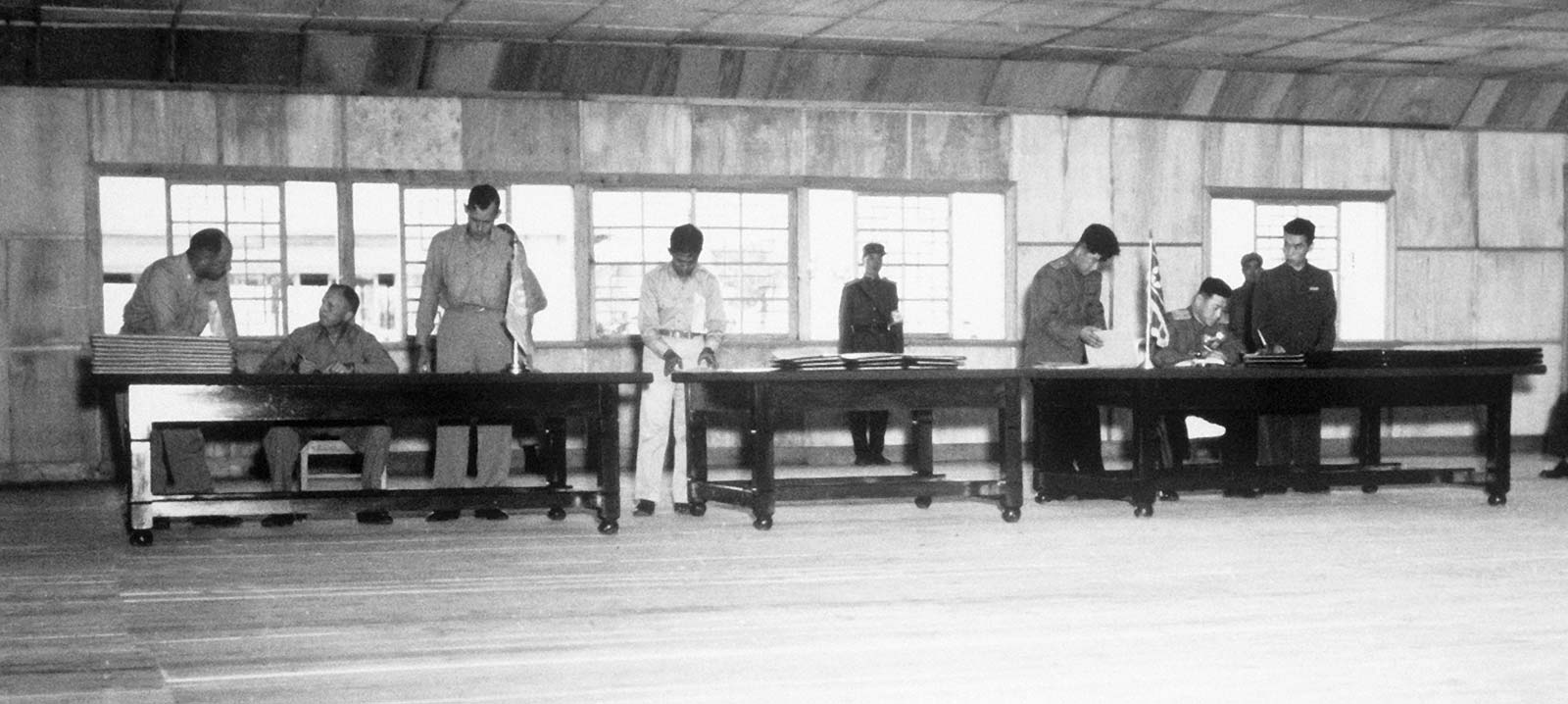

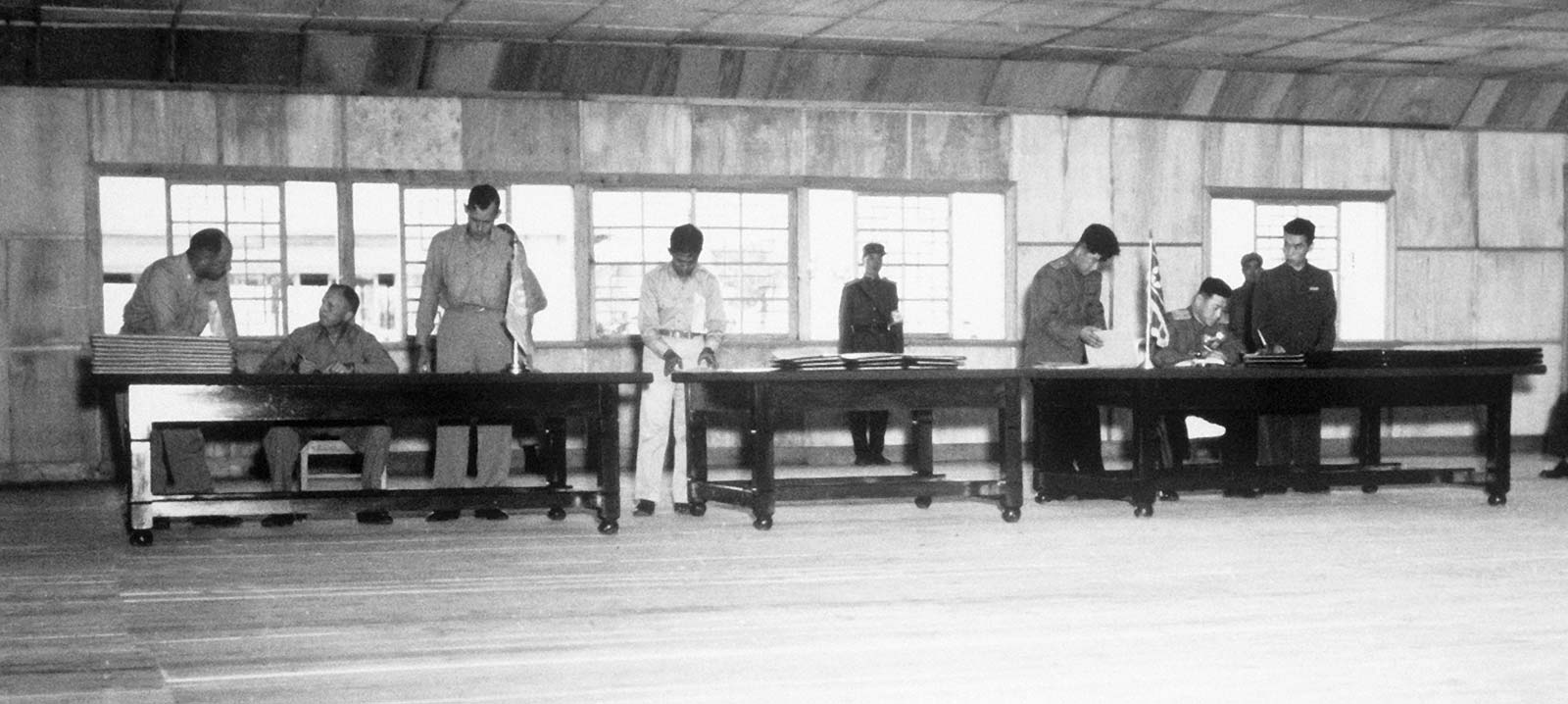

. He participated in the truce talks, which concluded with the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement

The Korean Armistice Agreement (; zh, t=韓國停戰協定 / 朝鮮停戰協定) is an armistice that brought about a cessation of hostilities of the Korean War. It was signed by United States Army Lieutenant General William Kelly Harrison Jr ...

on July 27, 1953. Harrison completed his career as the commanding general of U.S. Caribbean Command in early 1957.

Early career

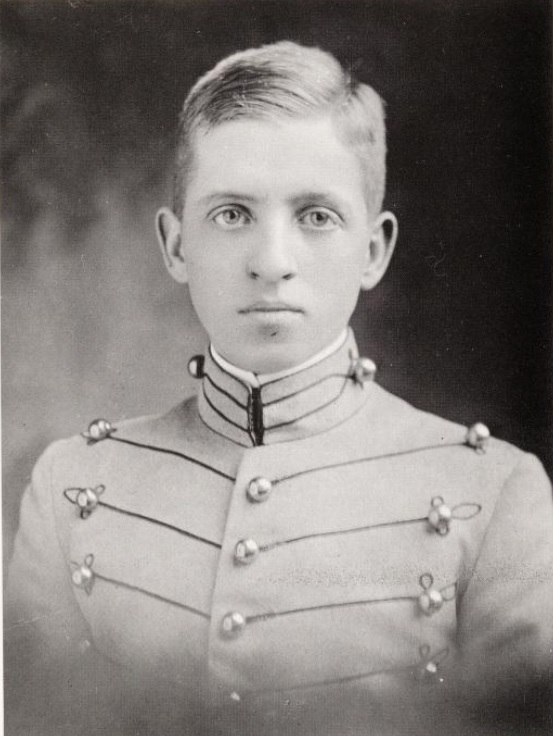

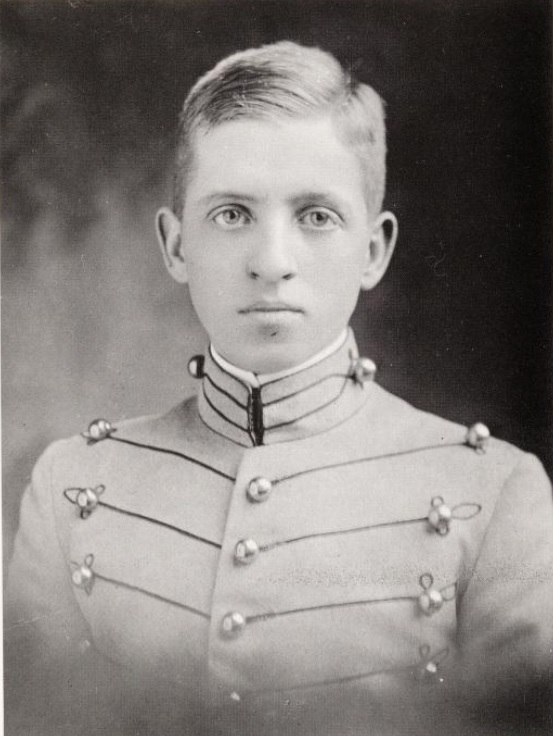

William Kelly Harrison Jr. was born on September 7, 1895, inWashington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

as the son of Naval

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operatio ...

officer and future Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

recipient, William Kelly Harrison and his wife Kate Harris. He was a direct descendant of President William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

. Following high school, William Jr. received a senatorial appointment from Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York (state), New York, General George Washington stationed his headquarters in West Point in the summer and fall of 1779 durin ...

in May 1913.

Harrison graduated with a

Harrison graduated with a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, B.S., B.Sc., SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree that is awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Scienc ...

degree on April 20, 1917, shortly following the United States entry into World War I, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the cavalry branch. He was subsequently ordered to Camp Lawrence J. Hearn, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, where he joined the 1st Cavalry Regiment.

He was subsequently ordered with the regiment to Douglas, Arizona

Douglas is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, that lies in the north-west to south-east running Sulphur Springs Valley. Douglas has a Douglas, Arizona Port of Entry, border crossing with Mexico at Agua Prieta and a history of min ...

, from which his unit participated in the guard duties on the Mexican Border. Harrison reached consecutively the ranks of first lieutenant and captain and returned to West Point Military Academy as an instructor of French and Spanish languages. While in this capacity, he also completed advanced languages courses in French and Spanish.

Harrison was later transferred to the 7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Irish air " Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune. The regiment participated in some of the largest ba ...

at Fort Bliss

Fort Bliss is a United States Army post in New Mexico and Texas, with its headquarters in El Paso, Texas. Established in 1848, the fort was renamed in 1854 to honor William Wallace Smith Bliss, Bvt.Lieut.Colonel William W.S. Bliss (1815–1853 ...

, Texas and served with that unit until early 1923, when he was ordered to Washington, D.C. for duty on the staff of the Army War College. He was promoted to major during his service there and left for the Philippines in 1925, where he was attached to the 26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippine Scouts

The Philippine Scouts ( Filipino: ''Maghahanap ng Pilipinas''/''Hukbong Maghahanap ng Pilipinas'') was a military organization of the United States Army from 1901 until after the end of World War II. These troops were generally Filipinos and ...

) at Camp Stotsenburg on Luzon

Luzon ( , ) is the largest and most populous List of islands in the Philippines, island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the List of islands of the Philippines, Philippine archipelago, it is the economic and political ce ...

.

Following his return stateside in 1932, Harrison was attached to the 7th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in Ge ...

, Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

. While stationed at Fort Riley, he completed the advanced course at the Army Cavalry School there and served on the Cavalry Board and as a troop commander with the 9th Cavalry Regiment

The 9th Cavalry Regiment is a parent cavalry regiment of the United States Army. Historically, it was one of the Army's four segregated African-American regiments and was part of what was known as the Buffalo Soldiers. The regiment saw combat d ...

.

Harrison was ordered to the Army Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas in June 1936 and graduated one year later. He then joined the faculty of the school and served as an instructor of tactics until September 1937, when he was ordered to the Army War College for instruction.

He graduated in July 1938 and joined the 6th Cavalry Regiment

The 6th Cavalry ("Fighting Sixth'") is a regiment of the United States Army that began as a regiment of cavalry in the American Civil War. It currently is organized into aviation squadrons that are assigned to several different combat aviation ...

at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

. Harrison remained in that assignment until August 1939, when he was attached to the War Plans Division, War Department General Staff

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, als ...

in Washington, D.C. While in this capacity, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on July 1, 1940.

World War II

Stateside service

Following the American entry into World War II, Harrison was promoted to the temporary rank of colonel on December 11, 1941, just four days after theJapanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

. He was appointed the deputy chief of the Strategy and Policy Group, War Plans Division, War Department General Staff and also was given additional duty at Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. ...

's Committee on Allocation of Responsibilities which was given the job of figuring out a reorganization of the Army high command. For his service in this capacity, Harrison was promoted to the temporary rank of brigadier general on June 26, 1942.

He was subsequently ordered to Camp Butner

Camp Butner was a United States Army installation in Butner, North Carolina, during World War II. It was named after Army general and North Carolina native Henry W. Butner. Part of it was used as a POW camp for German prisoners of war in the Unit ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, where he was attached to the 78th Infantry Division under Major General Edwin P. Parker Jr.

Edwin Pearson Parker Jr. (July 27, 1891 – June 7, 1983) was a senior officer in the United States Army. Parker commanded the 78th Infantry Division during the Ardennes-Alsace, Rhineland, and Central Europe, campaigns of World War II. Under hi ...

as Assistant Division Commander (ADC). Harrison then participated in the training of replacements for units serving overseas but suffered a minor injury on an obstacle course in December 1942. While recuperating, he received a telephone call from Major General Leland Hobbs, then in command of the 30th Infantry Division, informing him about his new assignment with Hobbs' 30th Division.

Harrison was replaced by Brigadier General John K. Rice and appointed ADC under Hobbs, who tasked him with organization of the 30th Infantry Division's training at Camp Blanding

Camp Blanding Joint Training Center is the primary military reservation and training base for the Florida National Guard, both the Florida Army National Guard and certain nonflying activities of the Florida Air National Guard. The installation ...

, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

. Harrison and Hobbs had known each other from West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

, where Hobbs was a member of the Class of 1915. They also were in the same class at the Army Command and General Staff School in 1937.

Billy Harrison had almost no respect for Hobbs as a leader of the troops. From Harrison's point of view, Hobbs violated every principle of leadership except one: He demanded obedience and gave it to his superiors. But in almost every other aspect, from training and disciplining men to planning battle operations in the field, Harrison described Hobbs as being " a Barracks soldier", who accustomed himself to applause.

Despite this, Harrison remained loyal to Hobbs, who never received anything than support from his ADC. On the other hand, Harrison benefited from Hobbs's apparent weakness, when he had the opportunity to be with his men during the training and later in combat.

Harrison participated in the training of his troops for the upcoming Tennessee Maneuvers in September–November 1943, where the 30th Division showed considerable alertness and skills. Following the maneuvers, the division moved to Camp Atterbury

Camp Atterbury-Muscatatuck is a federally owned military post, licensed to and operated by the Indiana National Guard, located in south-central Indiana, west of Edinburgh, Indiana and U.S. Route 31. The camp's mission is to provide full logis ...

, Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

, where it concentrated on preparation for movement overseas.

Overseas duty

Harrison led a divisional advanced party overseas by the end of January 1944 and spent the next several months in intensive training inEngland

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. The 30th Infantry Division departed for France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in June that year and landed at Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors of the amphibious assault component of Operation Overlord during the Second World War.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies of World War II, Allies invaded German military administration in occupied Fra ...

, Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

on June 11, 1944. Harrison participated in the combat at Vire-et-Taute Canal and on Vire River

The Vire () is a river in Normandy, France whose course crosses the ''departments of France, départements'' of Calvados (department), Calvados and Manche, flowing through the towns of Vire, Saint-Lô and Isigny-sur-Mer, finally flowing out into ...

and quickly won the admiration of his troops by accompanying them on the front lines with M3 submachine gun

The M3 is an American .45 ACP, .45-caliber submachine gun adopted by the U.S. Army on 12 December 1942, as the United States Submachine Gun, Cal. .45, M3.Iannamico, Frank, ''The U.S. M3-3A1 Submachine Gun'', Moose Lake Publishing, , (1999), pp. ...

in hand. He also spent his first night in France in a trench with combat troops.

On July 25, 1944, the 30th Infantry Division participated in combat near Saint-Lô

Saint-Lô (, ; ) is a Communes of France, commune in northwest France, the capital of the Manche department in the region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy.Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was an offensive launched by the First United States Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take advantage of the dis ...

, an offensive with the intention to advance into Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

. The offensive was to begin with a major saturation bombing of the enemy with the troops then moving in afterward, but due to inaccurate plane navigation, the planes erroneously bombed their own men. More than 600 men were hit, many killed, including Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, Commander of Army Ground Forces

The Army Ground Forces were one of the three autonomous components of the Army of the United States during World War II, the others being the Army Air Forces and Army Service Forces. Throughout their existence, Army Ground Forces were the la ...

.

Even though Harrison's command group was located in the rear, he returned deliberately to the forward area shortly before the bombing began. He was thrown down by the blast of German artillery fire, but was unharmed. Realizing that the success of the entire operation depended on the 30th Infantry Division carrying out its mission, Harrison began analyzing the situation and found out that the divisional Sherman tank

The M4 Sherman, officially medium tank, M4, was the medium tank most widely used by the United States and Western Allies in World War II. The M4 Sherman proved to be reliable, relatively cheap to produce, and available in great numbers. I ...

s were totally disorganized and demoralized infantry was spread in the area. Moreover, the commanding officer of 120th Infantry Regiment

The 120th Infantry Regiment ("Third North Carolina") is an infantry regiment of the United States Army National Guard.

The unit is an organic element of the 30th Heavy Brigade Combat Team (United States), 30th Heavy Brigade Combat Team of the N ...

, Colonel Hammond D. Birks was located somewhere in the forward area and his jeep was knocked out.

Harrison ordered the commander to get his tanks in battle formation and get ready for action and evacuated Colonel Birks to safety. He took a soldier with a bazooka

The Bazooka () is a Man-portable anti-tank systems, man-portable recoilless Anti-tank warfare, anti-tank rocket launcher weapon, widely deployed by the United States Army, especially during World War II. Also referred to as the "stovepipe", th ...

through a hedgerow and ordered him to attack a German tank nearby. The soldier hit the German tank several times, but panicked and ran into the open, where he was killed. Harrison crawled back and came upon four American tanks in a neighboring field, who were waiting out the enemy shelling with their hatches shut tight. He climbed on the commander's tank and forced the crew to open the hatch by beating on the tank's turret, subsequently ordering the general attack, which was successful. For his heroism in action, he was decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest decoration of the United States military for valor in combat.

Harrison then participated in the Battle of Mortain, the German drive to Avranches in mid-August 1944. The 30th Division clashed with the elite 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler

The 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler or SS Division Leibstandarte, abbreviated as LSSAH (), began as Adolf Hitler's personal bodyguard unit, responsible for guarding the Führer's person, offices, and residences. Initially th ...

. The 30th Division then advanced through Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

and Harrison distinguished himself again on September 2, 1944, while leading the Task Force of his division.

He was riding with the forward elements of his Task Force heading to Rumilly, when his column was ambushed by enemy tanks. Harrison's jeep was hit in the radiator and he was struck by an enemy 75mm tank shell, hitting his right shoulder, arm and leg. Harrison escaped from the damaged vehicle and hit the ditch, where he immediately dispatched his aide and driver to contact the next ranking officer in order that he might continue the advance. He did not mention his wounds, which were not visible due to his raincoat and crawled approximately 600 yards to the rear of the column in order to give further instructions for continuing the mission.

Harrison fainted momentarily due to his wounds, but refused to be evacuated until he had contacted his subordinates and instructed them in the continuation of the attack. By that time, General Hobbs had arrived and following the discovery of Harrison's wounds, he ordered Harrison's evacuation. For bravery in action, he was decorated with the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against a ...

and also received the Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the president to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, ...

for his wounds, of which he was most proud.

He spent a week in the First Army Hospital in Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

and rejoined his division in the Belgian town of Tongres

Tongeren (; ; ; ) is a city and former municipality located in the Belgian province of Limburg, in the southeastern corner of the Flemish region of Belgium. Tongeren is the oldest town in Belgium, as the only Roman administrative capital with ...

, where the division's progress was halted due to fuel shortages and quagmire roads. The 30th Division then proceeded to the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, where they liberated the town of Kerkrade

Kerkrade (; Kerkrade dialect, Ripuarian: ; ; or ''Kirchrath'') is a town and a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the southeast of Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg, the southernmost province of the Netherlands. It forms part of the P ...

on September 25, 1944, and advanced to Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, where they took part in the combat on the Siegfried Line and subsequently in the battle of the heavily defended city of Aachen on October 2.

The 30th Infantry Division was ordered for rest and refit to the rear by the end of November 1944 and transferred to the

The 30th Infantry Division was ordered for rest and refit to the rear by the end of November 1944 and transferred to the Ninth United States Army

The Ninth Army was a field army of the United States Army, most recently garrisoned at Caserma Ederle, Vicenza, Italy. It was the United States Army Service Component Command of United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM or AFRICOM).

Activated just ...

under Lieutenant General William H. Simpson

General William Hood Simpson (18 May 1888 – 15 August 1980) was a senior United States Army officer who served with distinction in both World War I and World War II. He is best known for being the commanding general of the Ninth United Sta ...

. Harrison was tasked by Simpson himself to conduct a refresher course for all infantry and artillery commanders in the Ninth United States Army, down to the battalion level. Harrison lectured the tactics employed by his command in the taking of several towns and then took the entire class to the field to Sankt Jöris near Aachen, where artillery and tanks were set up to demonstrate how they had been used in the attack there.

Harrison and 30th Division returned to the front lines following the launch of the massive German offensive in the Ardennes on December 17, 1944, and participated in combat in the Malmedy-Stavelot area. Hobbs tasked Harrison with the command of the task force, consisting of the 119th Infantry Regiment, which later repelled a German assault at La Gleize

La Gleize (; ) is a village of Wallonia and a district of the municipality of Stoumont, located in the province of Liège, Belgium.

It was a municipality before the fusion of 1977. La Gleize is located on a rocky outcrop overlooking the valley ...

. Harrison and his task force destroyed or captured 178 enemy armored vehicles, including 39 tanks.

He was out of action during January 1945, when he suffered an infection requiring surgery. Following his return at the beginning of February 1945, Harrison was visited by General William H. Simpson, the commanding general of the Ninth United States Army, who presented him with the Army Distinguished Service Medal

The Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a military decoration of the United States Army that is presented to soldiers who have distinguished themselves by exceptionally meritorious service to the government in a duty of great responsibility. ...

for his previous service with the War Plans Division, War Department General Staff, where he proposed a new concept of organization.

During March 1945, the 30th Division was located in the rear for rest and refit and conducted training for its next deployment. Harrison took part in the crossing of Rhine River on March 23, and advanced further into Germany. After taking Hamelin

Hameln ( ; ) is a town on the river Weser in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Hameln-Pyrmont and has a population of roughly 57,000. Hamelin is best known for the tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

History

Hameln ...

and Braunschweig

Braunschweig () or Brunswick ( ; from Low German , local dialect: ) is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Lower Saxony, Germany, north of the Harz Mountains at the farthest navigable point of the river Oker, which connects it to the ...

at the beginning of April 1945, the 30th Division Task Force under Harrison's command discovered two large groups of Hungarian Jewish women at Teutoburg Forest

The Teutoburg Forest ( ; ) is a range of low, forested hills in the German states of Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia. Until the 17th century, the official name of the hill ridge was Osning. It was first renamed the ''Teutoburg Forest'' ...

.

On April 13, 1945, Harrison participated in the efforts to save 2,400 prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp

Neuengamme was a network of Nazi concentration camps in northern Germany that consisted of the main camp, Neuengamme, and List of subcamps of Neuengamme, more than 85 satellite camps. Established in 1938 near the village of Neuengamme, Hamburg, N ...

subcamp at Farsleben

Farsleben is a village and a former municipality in the Börde district in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to th ...

, whom they found locked in train boxcars. The 30th Division then proceeded eastward and halted its advance on the Elbe River

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Germany and flo ...

at Grunewald Grunewald is the name of both a locality and a forest in Germany:

* Grunewald (forest)

* Grunewald (locality)

Grünewald may refer to:

* Grünewald (surname)

* Grünewald, Germany, a municipality in Brandenburg, Germany

* Grünewald (Luxembourg), ...

linking up with Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

forces.

For his service with the 30th Infantry Division, Harrison received the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievemen ...

and two Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious a ...

s. The Allies bestowed him with several decorations including: the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

, the Croix de Guerre with Palm by France, the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

by Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, the Order of Orange-Nassau

The Order of Orange-Nassau () is a civil and military Dutch order of chivalry founded on 4 April 1892 by the queen regent, Emma of the Netherlands.

The order is a chivalric order open to "everyone who has performed acts of special merits for ...

by the Netherlands and the Order of the Red Banner

The Order of the Red Banner () was the first Soviet military decoration. The Order was established on 16 September 1918, during the Russian Civil War by decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. It was the highest award of S ...

by the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

Postwar service

Harrison then participated in the occupation duty in Germany inMagdeburg

Magdeburg (; ) is the Capital city, capital of the Germany, German States of Germany, state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is on the Elbe river.

Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archbishopric of Mag ...

until June 1945, when he was appointed the acting commanding general of the 2nd Infantry Division located between Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

and Pilsen, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. He returned to the United States by the end of July and commanded the Second Division during the preparations for combat deployment to the Pacific area.

He was relieved by Major General Edward M. Almond in September 1945 and assumed duty as his assistant division commander. Due to the surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was Hirohito surrender broadcast, announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally Japanese Instrument of Surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, End of World War II in Asia, ending ...

, the deployment to the Pacific was canceled and Harrison served with the 2nd Division at Camp Swift, Texas

Camp Swift is a census-designated place (CDP) in Bastrop County, Texas, United States. The population was 7,943 at the 2020 census. Camp Swift began as a United States Army training base built in 1942. It is named after Major General Eben Swi ...

until April 1946. Harrison was then appointed commanding general at Camp Carson

Fort Carson is a United States Army post located directly south of Colorado Springs in El Paso, Pueblo, Fremont, and Huerfano counties, Colorado, United States. The developed portion of Fort Carson is located near the City of Colorado Springs ...

, Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

, where he was responsible for the demobilization of troops returning from war zones in Europe and Pacific.

In November 1946, Harrison was reverted to his permanent rank of colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

and ordered to Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, where he was attached to the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (), or SCAP, was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) ...

under General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

as Executive for Administrative Affairs and Reparations. While in this capacity, he collaborated closely with MacArthur and was responsible for the restoration of the Japanese economy as rapidly as possible.

He remained in this capacity until January 1947, when he was appointed commanding officer of the General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and also held additional duty as the executive officer of the Far East Command.

Harrison was promoted again to brigadier general on January 24, 1948, and appointed Chief of the Reparations Section at the headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and held this assignment until December 1948, when he was ordered back to the United States.

He was subsequently appointed Chief of the Armed Forces Information and Education Division of the Department of the Army in Washington, D.C. and was promoted to major general on March 11, 1949. While in this capacity, Harrison was responsible for the propaganda and university extension courses. He didn't like that job and following the outbreak of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, he applied to be assigned to a field command, hoping that the Army Chief of Personnel, Matthew B. Ridgway

Matthew Bunker Ridgway (3 March 1895 – 26 July 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Although he s ...

, who was his friend and West Point classmate, would help him.

Unfortunately, Ridgway couldn't help him at the time and offered him a post as the commanding general of Fort Dix

Fort Dix, the common name for the Army Support Activity (ASA) located at Joint Base McGuire–Dix–Lakehurst, is a United States Army post. It is located south-southeast of Trenton, New Jersey. Fort Dix is under the jurisdiction of the Air Fo ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

with additional duty as the commanding general of the 9th Infantry Division. Harrison accepted the offer in September 1950 and was responsible for the training of replacements for troops both in Europe and South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

. During sixteen-week training cycles, he had to transform young men into effective soldiers, but his methods were not met with understanding by some of the recruits' parents and also with some unfavorable press.

The night marches and forced marches with packs caused complaints to Congressmen

A member of congress (MOC), also known as a congressman or congresswoman, is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The ...

. When the father of one recruit was invited to spend a week at the barracks with his son, he changed his mind and upon returning home, he wrote a second letter to the editor of the newspaper, withdrawing all his criticism.

Harrison also ordered total racial integration of living accommodations at Fort Dix. It should be mentioned that he was no racist, but neither was he a civil rights activist. He did that because he needed his barracks to run in a more efficient manner. The barracks for white recruits were overcrowded and the ones for African Americans were half empty. The training was also racially integrated by Harrison.

Korean War

Harrison was finally ordered to South Korea in December 1951 and appointed deputy commander of the

Harrison was finally ordered to South Korea in December 1951 and appointed deputy commander of the Eighth United States Army

The Eighth Army is a U.S. field army which commands all United States Army forces in South Korea. It is headquartered at the Camp Humphreys in the Anjeong-ri of Pyeongtaek, Pyeongtaek, South Korea.James Van Fleet

General (United States), General James Alward Van Fleet (19 March 1892 – 23 September 1992) was a United States Army officer who served during World War I, World War II and the Korean War. Van Fleet was a native of New Jersey, who was raised i ...

, whom he respected as a combat troop leader. After reporting to Van Fleet, Harrison inspected every 8th Army combat division located on the Jamestown Line

The Jamestown Line was a series of defensive positions occupied by United Nations forces in the Korean War. Following the end of the 1951 Chinese Spring Offensive and the UN May-June 1951 counteroffensive, the war largely became one of attrition ...

(including American, British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

, South Korean and United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the South Korea, Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first attempt at collective security by the U ...

troops) from the Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea, also known as the North Sea, is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea.

Names

It is one of four ...

to the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it ...

.

He gained awareness of the situation on the front, terrain and enemy positions, but there were no major military operations, just a stalemate. The North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders China and Russia to the north at the Yalu River, Yalu (Amnok) an ...

ns and U.N. troops were located on the Jamestown Line and truce talks between United Nations and North Korea were already in effect. However Ridgway was not satisfied with one member of the U.N. negotiation team, Major General Claude B. Ferenbaugh

Claude Birkett Ferenbaugh (16 March 1899–10 September 1975) was a United States Army Lieutenant general (United States), lieutenant general. He served as the operations officer of the U.S. II Corps in North African Campaign, Africa during Wor ...

and replaced him with Harrison in January 1952.

Harrison was attached to the U.S. team under Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy and participated in the regular negotiations with North Korean and Chinese representatives at Panmunjon. The negotiations were ineffective and the North Korean and Chinese used the truce talks just for propaganda purposes and to strengthen their positions on the Jamestown Line. Joy was planning his own departure in mid-1952 and recommended Harrison as his replacement.

Ridgway agreed and announced the change of command to Washington, where it was confirmed in May 1952, when Harrison was appointed senior member of the Korean Armistice Delegation. He also nominated Harrison for the temporary rank of lieutenant general, but Armed Service Committee rejected the promotion.

In May 1952, General Mark W. Clark, another West Point classmate and friend of Harrison, succeeded Ridgway as Commander-in-Chief, United Nations Command Korea and urged Harrison's promotion again. The Army Chief of Staff, General J. Lawton Collins, who was also a West Point classmate of Harrison, convinced the committee and Harrison was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general on September 8, 1952.

Clark later commented:

Following the promotion, Harrison was appointed the deputy commanding general and chief of staff of the Far East Command under Clark and retained his assignment as the senior member in the truce talks team. He participated in the regular meetings with North Korean delegation led by General

Following the promotion, Harrison was appointed the deputy commanding general and chief of staff of the Far East Command under Clark and retained his assignment as the senior member in the truce talks team. He participated in the regular meetings with North Korean delegation led by General Nam Il

Nam Il (5 June 1915 – 7 March 1976) was a Russian-born North Korean military officer and co-signer of the Korean Armistice Agreement.

Biography

Nam was born Yakov Petrovich Nam () probably in the Russian Far East. Due to a Soviet policy, Na ...

and had to handle more North Korean attempts to use the truce talks as a platform for propaganda. He despised the communists, who he regarded with contempt as ''common criminals'' and for example in June 1952, he left the truce meeting, when he saw that the negotiation was without result, leaving North Korean General Nam Il flabbergasted.

In September 1953, Harrison assumed duties as the deputy commanding general and chief of staff of the Far East Command under Clark and remained in that capacity under General John E. Hull

John Edwin Hull (26 May 1895 – 10 June 1975) was a United States Army general, former Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army, commanded Far East Command (United States), Far East Command from 1953 to 1955 and the U.S. Army, Pacific from ...

, who replaced Clark in October 1953. Harrison served in the Far East until May 1954, when he returned to the United States for a new assignment. For his service in Korea during the armistice negotiations and later with the Far East Forces, he was decorated with the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

The Navy Distinguished Service Medal is a military decoration of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps which was first created in 1919 and is presented to Sailors and Marines to recognize distinguished and exceptionally meritorio ...

. Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen B ...

awarded him the Companion of the Most Honorable Order of the Bath.

A 1952 report prepared in Pyongyang by the non-governmental and historically Communist-affiliated International Association of Democratic Lawyers

International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) is an international organization of left-wing and progressive jurists' associations with sections and members in 50 countries and territories. Along with facilitating contact and exchange of v ...

claimed that Harrison had overseen the Sinchon Massacre, an alleged massacre of civilians which North Korea claims was perpetrated by the US and South Korea. The report claimed that a General "Harrison" had personally carried out atrocities and photographed them. Harrison was reportedly shocked by the claim.''Facts Forum'' vol. 4, no. 6 (1955), p. 5 Investigative reports have concluded there was no Harrison in Sinchon at the time, and that this was either a pseudonym of someone else or a false claim. Institute for Korean Historical Studies. 《사진과 그림으로보는 북한현대사》 p91~p93

Later service

Upon his return stateside, Harrison was welcomed as a hero, who brought peace in Korea. He attended many parades and banquets, where he featured as speaker and was given honorary degrees from Wheaton College inIllinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

and Houghton College

Houghton University is a Private university, private Christian liberal arts college in Houghton, New York, United States. Houghton was founded in 1883 by Willard J. Houghton and is affiliated with the Wesleyan Church.New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

. Harrison was also featured as speaker at the Easter sunrise service at the famous Rose Bowl stadium

The Rose Bowl is an outdoor athletic stadium located in Pasadena, California, United States. Opened in October 1922, the stadium is recognized as a National Historic Landmark and a California Historic Civil Engineering landmark. With a modern al ...

in Pasadena, California

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commerci ...

.

He then arrived at the Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a International zone#Concessions, concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area gene ...

on June 16, 1954, and assumed duties as the commander-in-chief of the United States Caribbean Command with headquarters in Quarry Heights

This is a list of United States military installations in Panama, all of which fall within the former Canal zone. The U.S. military installations in Panama were turned over to local authorities by 1999.

Transition phases

In 1903, the Hay–Buna ...

. His main task was the defense of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

and its coast, which was divided into Atlantic and Pacific Sectors. Harrison arrived in a country with an unstable political situation, because a few months after his arrival, the President of Panama, José Antonio Remón Cantera

Colonel José Antonio Remón Cantera (11 April 1908 – 2 January 1955) was the 16th President of Panama, holding office from 1 October 1952 until his death on January 2, 1955. He was Panama's first military strongman and ruled the country behi ...

was assassinated and his successor, José Ramón Guizado

José Ramón Guizado Valdés (13 August 1899 – 2 November 1964) was the 17th President of Panama. He belonged to the National Patriotic Coalition (CNP).

Education

Guizado is an alumnus of Vanderbilt University, having earned a Bachelor ...

, was arrested for conspiracy and murder.

Harrison participated in many ceremonies including the Inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

of President Ernesto de la Guardia in October 1956 (as a member of the United States delegation). He also hosted President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

and then-Vice President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

in 1955.

He instituted military training exercises, both amphibious and paratroop, in the Canal Zone and forces came from the United States. Harrison intended to demonstrate to Panama's neighbors the capabilities of the United States Army. Harrison was succeeded by Lieutenant General Robert M. Montague at the end of January 1957 and returned to the United States, awaiting retirement. For his service in that capacity, Harrison was decorated by Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

and Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

.

Retirement

Harrison retired from the Army on February 28, 1957, after almost 40 years of service and settled in

Harrison retired from the Army on February 28, 1957, after almost 40 years of service and settled in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, where he served as executive director of the Evangelical Child Welfare Agency until 1960. Harrison served as president of the Officers' Christian Fellowship

Officers' Christian Fellowship (OCF) is a nonprofit Christian parachurch organization of 17,000 U.S. Military officers, family members, and friends found at installations throughout the military. Founded in 1943, the organization's purpose remain ...

from 1954 to 1972 and as president emeritus from 1972 until his death. He was also a member of the Lownes Free Church and the Alumni Association of the United States Military Academy and as a trustee of The Stony Brook School

The Stony Brook School is a private, Christian, co-educational, college-preparatory boarding and day school for grades 7–12 in Stony Brook, New York, United States. It was established in 1922 by John Fleming Carson and fellow members of ...

in Stony Brook, New York

Stony Brook is a political subdivisions of New York#Hamlet, hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in the Administrative divisions of New York#Town, Town of Brookhaven, New York, Brookhaven in Suffolk County, New York, United States, on the No ...

.

Harrison died on May 25, 1987, in Bryn Mawr Terrace, a nursing home in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

Bryn Mawr (, from Welsh language, Welsh for 'big hill') is a census-designated place (CDP) located in Pennsylvania, United States. It is located just west of Philadelphia along Lancaster Avenue, also known as U.S. Route 30 in Pennsylvania, U.S. ...

, aged 91. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is the largest cemetery in the United States National Cemetery System, one of two maintained by the United States Army. More than 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington County, Virginia.

...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

.

Decorations

Here is Lieutenant General Harrison's ribbon bar:Notes

Further reading

''A Man Under Orders: Lieutenant General William K. Harrison, Jr.''. LOCKERBIE, D BRUCE. Harper & Row, 1979. .External links

Arlington National Cemetery record

{{DEFAULTSORT:Harrison, William Kelly Jr. 1895 births 1987 deaths Military personnel from Washington, D.C. United States Military Academy alumni United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni United States Army War College alumni United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army Command and General Staff College faculty United States Army personnel of the Korean War Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Silver Star Recipients of the Legion of Merit Officers of the Legion of Honour American recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Companions of the Order of the Bath Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Officers of the Order of Orange-Nassau Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Panmunjom United States Army Cavalry Branch personnel United States Army generals of World War II United States Army generals