Willem Barents on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Willem Barentsz (; – 20 June 1597), anglicized as William Barents or Barentz, was a Dutch

In 1596, disappointed by the failure of previous expeditions, the States-General announced they would no longer subsidize similar voyages – but instead offered a high reward for anybody who ''successfully'' navigated the Northeast Passage. The Town Council of

In 1596, disappointed by the failure of previous expeditions, the States-General announced they would no longer subsidize similar voyages – but instead offered a high reward for anybody who ''successfully'' navigated the Northeast Passage. The Town Council of  Dealing with extreme cold, the crew realised that their socks would burn before their feet could even feel the warmth of a fire – and took to sleeping with warmed stones and cannonballs. They used the merchant fabrics aboard the ship to make additional blankets and clothing. The ship bore salted beef, butter, cheese, bread,

Dealing with extreme cold, the crew realised that their socks would burn before their feet could even feel the warmth of a fire – and took to sleeping with warmed stones and cannonballs. They used the merchant fabrics aboard the ship to make additional blankets and clothing. The ship bore salted beef, butter, cheese, bread,  Proving somewhat successful at hunting, the group caught

Proving somewhat successful at hunting, the group caught

The Dutch at the North pole and the Dutch in Maine

3 March 1857. The young cabin boy had died during the winter months in the shelter.

The wooden lodge where Barentsz' crew sheltered was found undisturbed by Norwegian

The wooden lodge where Barentsz' crew sheltered was found undisturbed by Norwegian  The amateur archaeologist Miloradovich's 1933 finds are held in the Arctic and Antarctic Museum in St. Petersburg. Dmitriy Kravchenko visited the site in 1977, 1979 and 1980 – and sent divers into the sea hoping to find the wreck of the large ship. He returned with a number of objects, which went to the Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Local Lore (Russia). Another small collection exists at the Polar Museum in

The amateur archaeologist Miloradovich's 1933 finds are held in the Arctic and Antarctic Museum in St. Petersburg. Dmitriy Kravchenko visited the site in 1977, 1979 and 1980 – and sent divers into the sea hoping to find the wreck of the large ship. He returned with a number of objects, which went to the Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Local Lore (Russia). Another small collection exists at the Polar Museum in

Website of the ''Stichting Expeditieschip Willem Barentsz''

/ref>

navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's prim ...

, cartographer

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

, and Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

explorer

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

.

Barentsz went on three expeditions to the far north in search for a Northeast passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP; , ) is the Arctic shipping routes, shipping route between the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islan ...

. He reached as far as Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; , ; ), also spelled , is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, considered the extreme points of Europe ...

and the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Ultimately the Kara, Barents and Laptev Seas are all ...

in his first two voyages, but was turned back on both occasions by ice. During a third expedition, the crew discovered Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

and Bear Island, but subsequently became stranded on Novaya Zemlya for almost a year. Barentsz died on the return voyage in 1597.

The Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; , ; ) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian territorial waters.World Wildlife Fund, 2008. It was known earlier among Russi ...

, among many other places, is named after him.

Life and career

Willem Barentsz was born around 1550 in the villageFormerum

Formerum () is a village on Terschelling in the province of Friesland, the Netherlands. It had a population of around 211 in January 2017.Terschelling

Terschelling (; ; Terschelling dialect: ''Schylge'') is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and an island in the northern Netherlands, one of the West Frisian Islands. It is situated between the islands of Vlieland and Ameland.

...

in the Seventeen Provinces

The Seventeen Provinces were the Imperial states of the Habsburg Netherlands in the 16th century. They roughly covered the Low Countries, i.e., what is now the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and most of the France, French Departments of Franc ...

, present-day Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. ''Barentsz'' was not his surname

In many societies, a surname, family name, or last name is the mostly hereditary portion of one's personal name that indicates one's family. It is typically combined with a given name to form the full name of a person, although several give ...

but rather his patronymic name

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (more specifically an avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor. It is the male equivalent of a matronymic.

Patronymics are used, ...

, short for ''Barentszoon'' " Barent's son".

A cartographer by trade, Barentsz sailed to Spain and the Mediterranean to complete an atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

of the Mediterranean region, which he co-published with Petrus Plancius

Petrus Plancius (; born Pieter Platevoet ; 1552 – 15 May 1622) was a Dutch- Flemish astronomer, cartographer and clergyman. Born, in Dranouter, now in Heuvelland, West Flanders, he studied theology in Germany and England. At the age of 24 ...

.

His career as an explorer was spent searching for a Northeast passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP; , ) is the Arctic shipping routes, shipping route between the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islan ...

in order to trade with China. He reasoned clear, open water north of Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

must exist since the sun shone 24 hours a day melting Arctic sea ice, indeed he thought the farther north one went the less ice there would be.

First voyage

On 5 June 1594, Barentsz left the island ofTexel

Texel (; Texels dialect: ) is a municipality and an island with a population of 13,643 in North Holland, Netherlands. It is the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea. The island is situated north of Den ...

aboard the small ship ''Mercury'', as part of a group of three ships sent out in separate directions to try to enter the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Ultimately the Kara, Barents and Laptev Seas are all ...

, with the hopes of finding the Northeast Passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP; , ) is the Arctic shipping routes, shipping route between the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islan ...

above Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. Between 23 and 29 June, Barentsz stayed at Kildin Island

Kildin (also Kilduin; , North Sami: Gieldasuolu) is a small Russian island in the Barents Sea, off the Russian shore and about 120 km from Norway. Administratively, Kildin belongs to the Murmansk Oblast of the Russian Federation.

Kildin ...

.

On 9 July, the crew encountered a polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a large bear native to the Arctic and nearby areas. It is closely related to the brown bear, and the two species can Hybrid (biology), interbreed. The polar bear is the largest extant species of bear ...

for the first time. After shooting and wounding it with a musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually dis ...

when it tried to climb aboard the ship, the seamen decided to capture it with the hope of bringing it back to Holland. Once leashed and brought aboard the ship however, the bear rampaged and had to be killed. This occurred in Bear Creek, Williams Island.

Upon discovering the Orange Islands, the crew came across a herd of approximately 200 walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large pinniped marine mammal with discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. It is the only extant species in the family Odobeni ...

es and tried to kill them with hatchets and pikes. Finding the task more difficult than they imagined, cold steel shattering against the tough hides of the animals, they left with only a few ivory tusks.

Barentsz reached the west coast of Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; , ; ), also spelled , is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, considered the extreme points of Europe ...

, and followed it northward before being forced to turn back in the face of large icebergs. Although they did not reach their ultimate goal, the trip was considered a success.

Jan Huyghen van Linschoten was a member of this expedition and the second.

Second voyage

The following year, Prince Maurice of Orange was filled with "the most exaggerated hopes" on hearing of Barentsz' previous voyage, and named him chief pilot and conductor of a new expedition, which was accompanied by six ships loaded with merchant wares that the Dutch hoped to trade with China. Setting out on 2 June 1595, the voyage went between the Siberian coast andVaygach Island

Vaygach Island () is an island in the Arctic Sea between the Pechora Sea and the Kara Sea.

Geography

Vaygach Island is separated from the Yugorsky Peninsula in the mainland by the Yugorsky Strait and from Novaya Zemlya by the Kara Strait. ...

. On 30 August, the party came across approximately 20 Samoyed "wild men" with whom they were able to speak, due to a crewmember speaking their language. 4 September saw a small crew sent to States Island to search for a type of crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

that had been noticed earlier. The party was attacked by a polar bear, and two sailors were killed.

Eventually, the expedition turned back upon discovering that unexpected weather had left the Kara Sea

The Kara Sea is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Ultimately the Kara, Barents and Laptev Seas are all ...

frozen. This expedition was largely considered to be a failure.

Third voyage

In 1596, disappointed by the failure of previous expeditions, the States-General announced they would no longer subsidize similar voyages – but instead offered a high reward for anybody who ''successfully'' navigated the Northeast Passage. The Town Council of

In 1596, disappointed by the failure of previous expeditions, the States-General announced they would no longer subsidize similar voyages – but instead offered a high reward for anybody who ''successfully'' navigated the Northeast Passage. The Town Council of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

purchased and outfitted two small ships, captained by Jan Rijp and Jacob van Heemskerk

Jacob van Heemskerck (3 March 1567 – 25 April 1607) was a Dutch explorer and naval officer. He is generally known for his victory over the Spanish at the Battle of Gibraltar, where he ultimately lost his life.

Early life

Jacob van Hee ...

, to search for the elusive channel under the command of Barentsz. They set off on 10 May or 15 May, and on 9 June discovered Bear Island.De Veer, Gerrit. "''The Three Voyages of William Barentsz to the Arctic Regions''" (English trans. 1609).

They discovered Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

on 17 June, sighting its northwest coast. On 20 June they saw the entrance of a large bay, later called Raudfjorden. On 21 June they anchored between Cloven Cliff and Vogelsang, where they "set up a post with the arms of the Dutch upon it." On 25 June they entered Magdalenefjorden, which they named ''Tusk Bay'', in light of the walrus tusks they found there. The following day, 26 June, they sailed into the northern entrance of Forlandsundet

Forlandsundet is an 88 km long sound separating Prins Karls Forland and Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzber ...

, but were forced to turn back because of a shoal, which led them to call the fjord ''Keerwyck'' ("inlet where one is forced to turn back"). On 28 June they rounded the northern point of Prins Karls Forland, which they named ''Vogelhoek'', on account of the large number of birds they saw there. They sailed south, passing Isfjorden and Bellsund, which were labelled on Barentsz's chart as ''Grooten Inwyck'' and ''Inwyck''.

The ships once again found themselves at Bear Island on 1 July, which led to a disagreement between Barentsz and Van Heemskerk on one side and Rijp on the other. They agreed to part ways, with Barentsz continuing northeast, while Rijp headed due north in an attempt to cross directly over the north pole to reach China. Barentsz reached Novaya Zemlya on 17 July. Anxious to avoid becoming entrapped in the surrounding ice, he intended to head for the Vaigatch Strait, but their ship became stuck within the many icebergs and floes. Stranded, the 16-man crew was forced to spend the winter on a barren bluff. After a failed attempt to melt the permafrost

Permafrost () is soil or underwater sediment which continuously remains below for two years or more; the oldest permafrost has been continuously frozen for around 700,000 years. Whilst the shallowest permafrost has a vertical extent of below ...

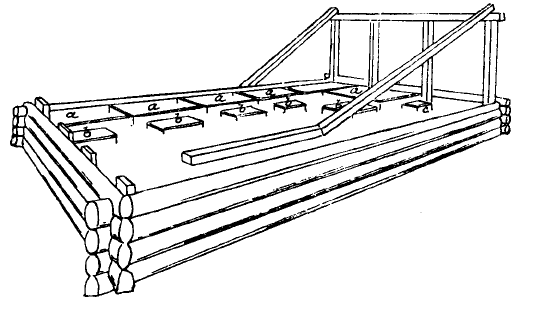

, the crew used driftwood and lumber from the ship to build a 7.8×5.5-metre lodge they called ''Het Behouden Huys'' (The Saved House).

Dealing with extreme cold, the crew realised that their socks would burn before their feet could even feel the warmth of a fire – and took to sleeping with warmed stones and cannonballs. They used the merchant fabrics aboard the ship to make additional blankets and clothing. The ship bore salted beef, butter, cheese, bread,

Dealing with extreme cold, the crew realised that their socks would burn before their feet could even feel the warmth of a fire – and took to sleeping with warmed stones and cannonballs. They used the merchant fabrics aboard the ship to make additional blankets and clothing. The ship bore salted beef, butter, cheese, bread, barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

, peas, beans, groats

Groats (or in some cases, "berries") are the hulled kernels of various cereal grains, such as oats, wheat, rye, and barley. Groats are whole grains that include the cereal germ and fiber-rich bran portion of the grain, as well as the endos ...

, flour, oil, vinegar, mustard, salt, beer, wine, brandy, hardtack

Hardtack (or hard tack) is a type of dense Cracker (food), cracker made from flour, water, and sometimes salt. Hardtack is inexpensive and long-lasting. It is used for sustenance in the absence of perishable foods, commonly during long sea voyage ...

, smoked bacon, ham and fish. Much of the beer froze, bursting the cask

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids ...

s. By 8 November Gerrit de Veer

Gerrit de Veer (–after 1598) was a Dutch officer on Willem Barentsz' second and third voyages of 1595 and 1596 respectively, in search of the Northeast passage.

De Veer kept a diary of the voyages and in 1597, was the first person to observe ...

, the ship's carpenter who kept a diary, reported a shortage of beer and bread, with wine being rationed four days later.

In January 1597, the crew became the first to witness and record the atmospheric anomaly of a polar mirage, now coined the Novaya Zemlya effect

The Novaya Zemlya effect is a polar mirage caused by high refraction of sunlight between atmospheric thermal layers. The effect gives the impression that the sun is rising earlier than it actually should, and depending on the meteorological si ...

due to this sighting.

Proving somewhat successful at hunting, the group caught

Proving somewhat successful at hunting, the group caught Arctic fox

The Arctic fox (''Vulpes lagopus''), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small species of fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Tundra#Arctic tundra, Arctic tundra biome. I ...

es in primitive traps. The raw flesh of the Arctic fox contains small amounts of vitamin C, which, unknown to the sailors, reduced the effects of scurvy. The crew were continually attacked by polar bears that infested the area where they camped. The bears turned the stranded and now empty ship into a wintertime abode. Primitive guns usually did not kill the bears on first or even second shot (unless well aimed at the heart) and were difficult to aim, while the cold and brittle metal weapons often shattered or bent.

By June, the ice had still not loosened its grip on the ship, and the remaining desperate scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

-ridden survivors took two open boats. Barentsz died at sea soon after on 20 June 1597. It is not known whether Barentsz was buried on the northern island of Novaya Zemlya, or at sea. It took seven more weeks for the boats to reach the Kola Peninsula

The Kola Peninsula (; ) is a peninsula in the extreme northwest of Russia, and one of the largest peninsulas of Europe. Constituting the bulk of the territory of Murmansk Oblast, it lies almost completely inside the Arctic Circle and is border ...

, where they were rescued by a Dutch merchant vessel commanded by former fellow explorer Jan Rijp who by that time had returned to the Netherlands and was on a second voyage, assuming the Barentsz crew to be lost, and found it by accident. By that time, only 12 crewmen remained. They did not reach Amsterdam until 1 November.Goorich, Frank Boott. "Man Upon the Sea", 1858. Sources differ on whether two men died on the ice floe and three in the boats, or three on the ice floe and two in the boats.De Peyster, John WattsThe Dutch at the North pole and the Dutch in Maine

3 March 1857. The young cabin boy had died during the winter months in the shelter.

Excavation and findings

seal hunt

Seal hunting, or sealing, is the personal or commercial hunting of Pinniped, seals. Seal hunting is currently practiced in nine countries: Canada, Denmark (in self-governing Greenland only), Russia, the United States (above the Arctic Circle ...

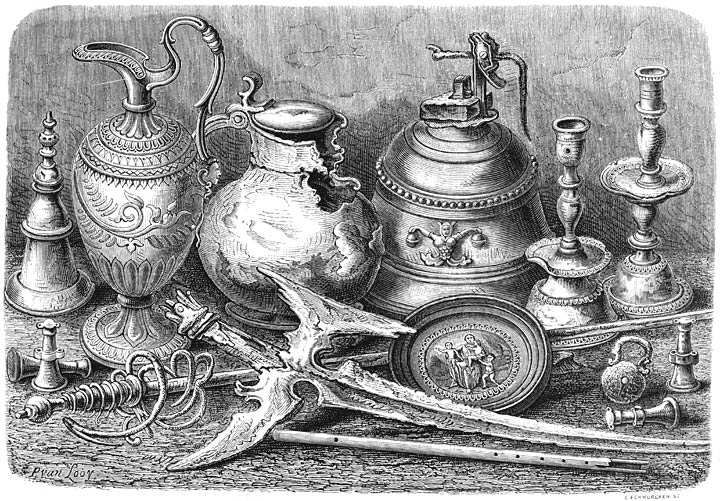

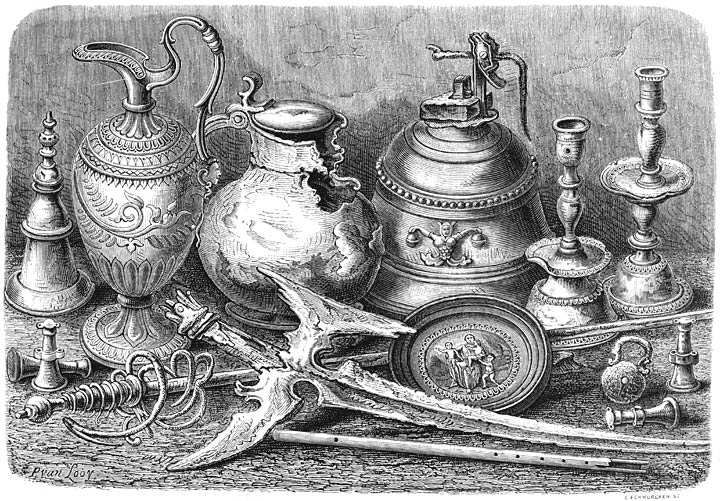

er Elling Carlsen in 1871. Making a sketch of the lodge's construction, Carlsen recorded finding two copper cooking pots, a barrel, a tool chest, clock, crowbar, flute, clothing, two empty chests, a cooking tripod and a number of pictures. Captain Gunderson landed at the site on 17 August 1875 and collected a grappling iron, two maps and a handwritten translation of Arthur Pet and Charles Jackman's voyages. The following year, Charles L.W. Gardiner also visited the site on 29 July where he collected 112 more objects, including the message by Barentsz and Heemskerck describing their settlement to future visitors. All of these objects eventually ended up in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The Rijksmuseum () is the national museum of the Netherlands dedicated to Dutch arts and history and is located in Amsterdam. The museum is located at the Museumplein, Museum Square in the stadsdeel, borough of Amsterdam-Zuid, Amsterdam South, ...

, after some had initially been held in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

.

The amateur archaeologist Miloradovich's 1933 finds are held in the Arctic and Antarctic Museum in St. Petersburg. Dmitriy Kravchenko visited the site in 1977, 1979 and 1980 – and sent divers into the sea hoping to find the wreck of the large ship. He returned with a number of objects, which went to the Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Local Lore (Russia). Another small collection exists at the Polar Museum in

The amateur archaeologist Miloradovich's 1933 finds are held in the Arctic and Antarctic Museum in St. Petersburg. Dmitriy Kravchenko visited the site in 1977, 1979 and 1980 – and sent divers into the sea hoping to find the wreck of the large ship. He returned with a number of objects, which went to the Arkhangelsk Regional Museum of Local Lore (Russia). Another small collection exists at the Polar Museum in Tromsø

Tromsø is a List of towns and cities in Norway, city in Tromsø Municipality in Troms county, Norway. The city is the administrative centre of the municipality as well as the administrative centre of Troms county. The city is located on the is ...

(Norway).

In 1992, an expedition of three scientists, a journalist and two photographers commissioned by the ''Arctic Centre'' at the University of Groningen

The University of Groningen (abbreviated as UG; , abbreviated as RUG) is a Public university#Continental Europe, public research university of more than 30,000 students in the city of Groningen (city), Groningen, Netherlands. Founded in 1614, th ...

, coupled with two scientists, a cook and a doctor sent by the '' Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute'' in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

, returned to the site, and erected a commemorative marker at the site of the cabin.

The location of Barentsz' wintering on the ice floes has become a tourist destination for icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

cruiseships operating from Murmansk

Murmansk () is a port city and the administrative center of Murmansk Oblast in the far Far North (Russia), northwest part of Russia. It is the world's largest city north of the Arctic Circle and sits on both slopes and banks of a modest fjord, Ko ...

.

Legacy

Two of Barentsz' crewmembers later published their journals, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten who had accompanied him on the first two voyages, and Gerrit de Veer who had acted as the ship's carpenter on the last two voyages. In 1853, the former ''Murmean Sea'' was renamedBarents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; , ; ) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian territorial waters.World Wildlife Fund, 2008. It was known earlier among Russi ...

in his honour. Barentsburg, the second largest settlement on Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

, Barentsøya

Barentsøya, anglicized as Barents Island, is an Arctic island in the Svalbard archipelago of Norway, lying between Edgeøya and Spitsbergen. To the north, in the sound between Barentsøya and Spitsbergen, lies the island of Kükenthaløya. To the ...

(Barents Island) and the Barents Region

The Barents Region is a name given, by advocates of establishing international cooperation after the fall of the Soviet Union, to the land along the coast of the Barents Sea, from Nordland county in Norway to the Kola Peninsula in Russia and bey ...

were also named after Barentsz.

In the late 19th century, the Maritime Institute Willem Barentsz was opened on Terschelling.

In 1878, the Netherlands christened the ''Willem Barentsz'' Arctic exploration ship.

In 1931, Nijgh & Van Ditmar published a play written by Albert Helman about Barentsz' third voyage, although it was never performed.

In 1946, the whaling ship

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Jap ...

''Pan Gothia'' was re-christened the ''Willem Barentsz''. In 1953, the second ''Willem Barentsz'' whaling ship was produced.

A protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

in the molecular structure of the fruit fly was named ''Barentsz'', in honour of the explorer.

Dutch filmmaker Reinout Oerlemans

Reinout Oerlemans (; born 10 June 1971) is a Dutch soap opera actor, film director, television presenter and television producer. He is the founder of the TV production company Eyeworks.

In 1989, while studying law at the University of Amsterd ...

released a film called '' Nova Zembla'' in November 2011. It is the first Dutch 3D feature film.

In 2011, a team of volunteers started building a replica of Barentsz' ship in the Dutch town of Harlingen. The plan was to have the ship ready by 2018, when the Tall Ships' Races was scheduled to visit Harlingen./ref>

References

Further reading

* * *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Barentsz, Willem 16th-century Dutch explorers 16th-century Dutch cartographers 1550s births 1597 deaths Deaths from scurvy Dutch polar explorers Explorers of Svalbard Explorers of the Arctic People from Terschelling