World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a

global conflict between two coalitions: the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

(or Entente) and the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

. Fighting took place mainly in

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and the

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, as well as in parts of

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and the

Asia-Pacific, and in Europe was characterised by

trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which combatants are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from a ...

; the widespread use of

artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

, machine guns, and

chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

(gas); and the introductions of

tanks

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; t ...

and

aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

. World War I was one of the

deadliest conflicts in history, resulting in an estimated

10 million military dead and more than 20 million wounded, plus some 10 million civilian dead from causes including

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

. The movement of large numbers of people was a major factor in the deadly

Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest docum ...

pandemic.

The

causes of World War I

The identification of the causes of World War I remains a debated issue. World War I began in the Balkans on July 28, 1914, and hostilities Armistice of 11 November 1918, ended on November 11, 1918, leaving World War I casualties, 17 million de ...

included the rise of

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and

decline of the Ottoman Empire

In the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire faced threats on numerous frontiers from multiple industrialised European powers as well as internal instabilities. Outsider influence, rise of nationalism and internal corruption demanded the Empire to lo ...

, which disturbed the long-standing

balance of power in Europe, and rising economic competition between nations driven by

industrialisation

Industrialisation ( UK) or industrialization ( US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for th ...

and

imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

. Growing tensions between the

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

s and in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

reached

a breaking point on 28 June 1914, when

Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip ( sr-Cyrl, Гаврило Принцип, ; 25 July 189428 April 1918) was a Bosnian Serb student who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie, Duchess von ...

, a

Bosnian Serb

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sr-Cyrl, Срби Босне и Херцеговине, Srbi Bosne i Hercegovine), often referred to as Bosnian Serbs ( sr-cyrl, босански Срби, bosanski Srbi) or Herzegovinian Serbs ( sr-cyrl, � ...

,

assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne.

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

blamed

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, and declared war on 28 July. After

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

mobilised in Serbia's defence, Germany declared war on Russia and

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, who had

an alliance. The

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

entered after Germany

invaded Belgium, and the Ottomans joined the Central Powers in November.

Germany's strategy in 1914 was to quickly defeat France then transfer its forces to the east, but its advance

was halted in September, and by the end of the year the

Western Front consisted of a near-continuous line of trenches from the English Channel to Switzerland. The

Eastern Front was more dynamic, but neither side gained a decisive advantage, despite costly offensives.

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

,

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

,

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and others joined in from 1915 onward.

Major battles, including at

Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

,

the Somme, and

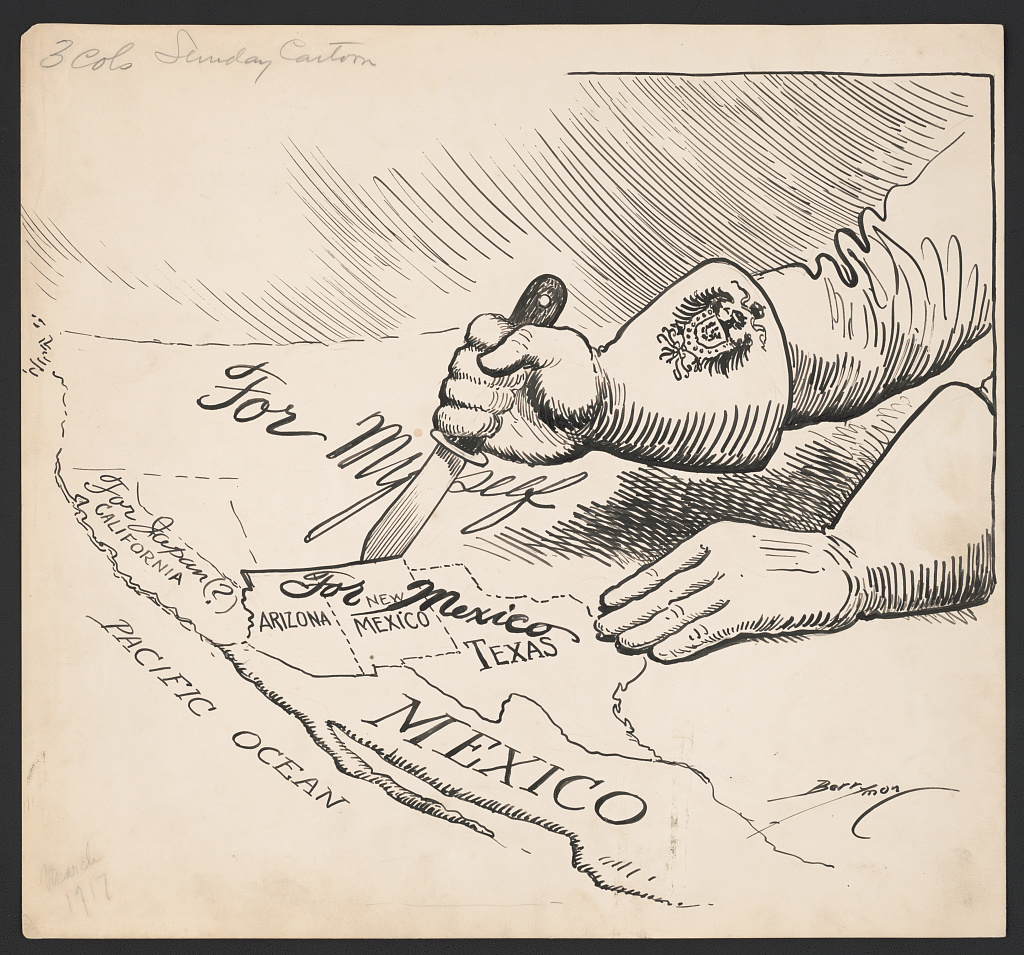

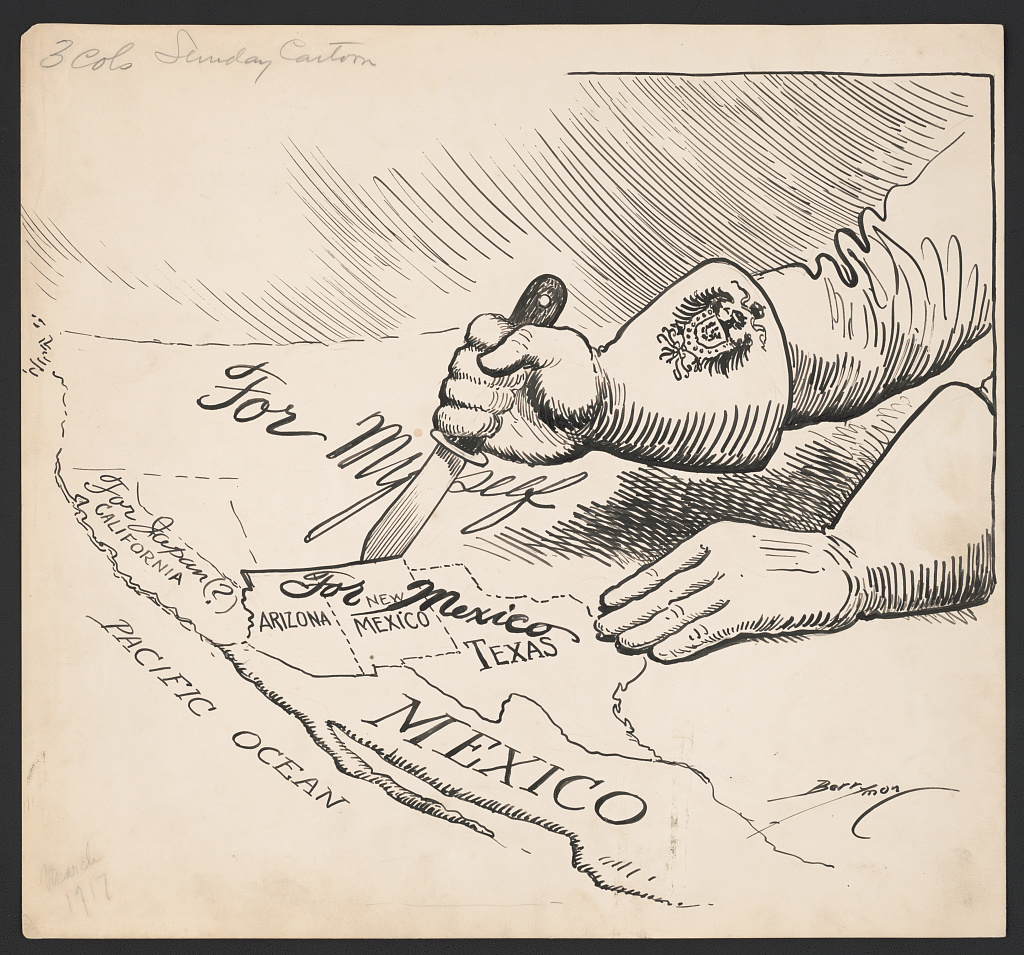

Passchendaele, failed to break the stalemate on the Western Front. In April 1917, the

United States joined the Allies after Germany resumed

unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning. The use of unrestricted submarine warfare has had significant impacts on international relations in ...

against Atlantic shipping. Later that year, the

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

seized power in Russia in the

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

;

Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

signed

an armistice with the Central Powers in December, followed by

a separate peace

''A Separate Peace'' is a Bildungsroman, coming-of-age novel by John Knowles, published in 1959. Based on his earlier short story "Phineas", published in the May 1956 issue of ''Cosmopolitan (magazine), Cosmopolitan'', it was Knowles's first p ...

in March 1918. That month, Germany launched

a spring offensive in the west, which despite initial successes left the

German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

exhausted and demoralised. The Allied

Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Imperial Germa ...

beginning in August 1918 caused a collapse of the German front line. Following the

Vardar Offensive

The Vardar offensive () was a World War I military operation, fought between 15 and 29 September 1918. The operation took place during the final stage of the Balkans Campaign (World War I), Balkans Campaign. On 15 September, a combined Allied A ...

, Bulgaria signed an

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

in late September. By early November, the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

had each signed armistices with the Allies, leaving Germany isolated. Facing

a revolution at home, Kaiser

Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

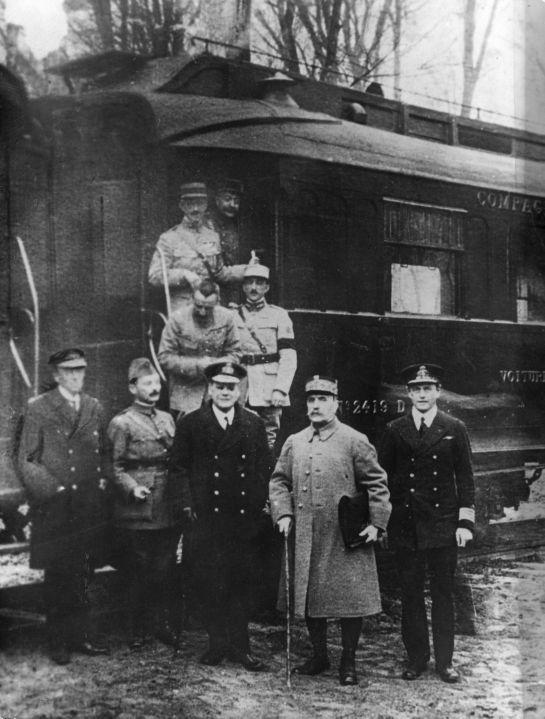

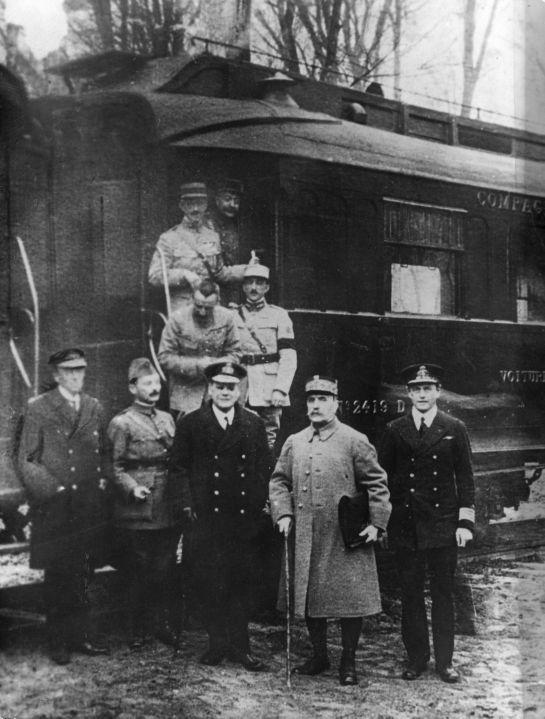

abdicated on 9 November, and the war ended with the

Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed in a railroad car, in the Compiègne Forest near the town of Compiègne, that ended fighting on land, at sea, and in the air in World War I between the Entente and their las ...

.

The

Paris Peace Conference of 1919–1920 imposed settlements on the defeated powers, most notably the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

, by which Germany lost significant territories, was disarmed, and was required to pay large

war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war. War reparations can take the form of hard currency, precious metals, natural resources, in ...

to the Allies. The dissolution of the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires redrew national boundaries and resulted in the creation of new independent states, including

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

,

Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, the

Baltic states

The Baltic states or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term encompassing Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, and the OECD. The three sovereign states on the eastern co ...

,

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, and

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

. The

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

was established to maintain world peace, but its failure to manage instability during the

interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

contributed to the outbreak of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in 1939.

Names

Before

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the events of 1914–1918 were generally known as the ''Great War'' or simply the ''World War''. In August 1914, the magazine ''

The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'' wrote "This is the Great War. It names itself."

In October 1914, the Canadian magazine ''

Maclean's

''Maclean's'' is a Canadian magazine founded in 1905 which reports on Canadian issues such as politics, pop culture, trends and current events. Its founder, publisher John Bayne Maclean, established the magazine to provide a uniquely Canadian ...

'' similarly wrote, "Some wars name themselves. This is the Great War." Contemporary Europeans also referred to it as "

the war to end war

"The war to end war" (now commonly phrased "the war to end all wars"; originally from the 1914 book ''The War That Will End War'' by H. G. Wells) is a term for the World War I, First World War (1914–1918). Originally an Ideal (ethics), idealist ...

" and it was also described as "the war to end all wars" due to their perception of its unparalleled scale, devastation, and loss of life. The first recorded use of the term ''First World War'' was in September 1914 by German biologist and philosopher

Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

who stated, "There is no doubt that the course and character of the feared 'European War' ... will become the first world war in the full sense of the word."

Background

Political and military alliances

For much of the 19th century, the major European powers maintained a tenuous

balance of power, known as the

Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general agreement among the great powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

. After 1848, this was challenged by Britain's withdrawal into so-called

splendid isolation

Splendid isolation is a term used to describe the 19th-century British diplomatic practice of avoiding permanent alliances from 1815 to 1902. The concept developed as early as 1822, when Britain left the post-1815 Concert of Europe, and continu ...

, the

decline of the Ottoman Empire

In the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire faced threats on numerous frontiers from multiple industrialised European powers as well as internal instabilities. Outsider influence, rise of nationalism and internal corruption demanded the Empire to lo ...

,

New Imperialism

In History, historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of Colonialism, colonial expansion by European powers, the American imperialism, United States, and Empire of Japan, Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

, and the rise of

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

under

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

. Victory in the 1870–1871

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

allowed Bismarck to

consolidate a

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

. Post-1871, the primary aim of French policy was to

avenge this defeat, but by the early 1890s, this had switched to the expansion of the

French colonial empire

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas Colony, colonies, protectorates, and League of Nations mandate, mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "Firs ...

.

In 1873, Bismarck negotiated the

League of the Three Emperors

The League of the Three Emperors or Union of the Three Emperors () was an alliance between the German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires, from 1873 to 1887. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck took full charge of German foreign policy from 1870 to h ...

, which included

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

,

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, and Germany. After the 1877–1878

Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

, the League was dissolved due to Austrian concerns over the expansion of Russian influence in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, an area they considered to be of vital strategic interest.

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Austria-Hungary then formed the 1879

Dual Alliance, which became the

Triple Alliance when Italy joined in 1882. For Bismarck, the purpose of these agreements was to isolate France by ensuring the three empires resolved any disputes among themselves. In 1887, Bismarck set up the

Reinsurance Treaty

The Reinsurance Treaty was a diplomatic agreement between the German Empire and the Russian Empire that was in effect from 1887 to 1890. The existence of the agreement was not known to the general public, and as such, was only known to a handful ...

, a secret agreement between Germany and Russia to remain neutral if either were attacked by France or Austria-Hungary.

For Bismarck, peace with Russia was the foundation of German foreign policy, but in 1890, he was forced to retire by

Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

. The latter was persuaded not to renew the Reinsurance Treaty by his new

Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

,

Leo von Caprivi

Georg Leo Graf von Caprivi de Caprara de Montecuccoli (English language, English: ''Count George Leo of Caprivi, Caprara, and Montecuccoli''; born Georg Leo von Caprivi; 24 February 1831 – 6 February 1899) was a German general and statesman. He ...

. This gave France an opening to agree to the

Franco-Russian Alliance

The Franco-Russian Alliance (, ), also known as the Dual Entente or Russo-French Rapprochement (''Rapprochement Franco-Russe'', Русско-Французское Сближение; ''Russko-Frantsuzskoye Sblizheniye''), was an alliance formed ...

in 1894, which was then followed by the 1904 ''

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and the French Third Republic, French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Fr ...

'' with Britain. The

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

was completed by the 1907

Anglo-Russian Convention

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ), was signed on August 31, 1907, in Saint Petersburg. It ended the two powers' longstanding rivalry in Cen ...

. While not formal alliances, by settling

longstanding colonial disputes in Asia and Africa, British support for France or Russia in any future conflict became a possibility. This was accentuated by British and Russian support for France against Germany during the 1911

Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis, was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in July 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, ...

.

Arms race

German economic and industrial strength continued to expand rapidly post-1871. Backed by Wilhelm II, Admiral

Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (; born Alfred Peter Friedrich Tirpitz; 19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral and State Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperi ...

sought to use this growth to build an

Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

, that could compete with the British

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. This policy was based on the work of US naval author

Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States Navy officer and historian whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His 1890 book '' The Influence of Sea Pow ...

, who argued that possession of a

blue-water navy

A blue-water navy is a Navy, maritime force capable of operating globally, essentially across the deep waters of open oceans. While definitions of what actually constitutes such a force vary, there is a requirement for the ability to exercise Co ...

was vital for global power projection; Tirpitz had his books translated into German, while Wilhelm made them required reading for his advisors and senior military personnel.

However, it was also an emotional decision, driven by Wilhelm's simultaneous admiration for the Royal Navy and desire to surpass it. Bismarck thought that the British would not interfere in Europe, as long as its maritime supremacy remained secure, but his dismissal in 1890 led to a change in policy and an

Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship tha ...

began. Despite the vast sums spent by Tirpitz, the launch of in 1906 gave the British a technological advantage. Ultimately, the race diverted huge resources into creating a German navy large enough to antagonise Britain, but not defeat it; in 1911, Chancellor

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg (29 November 1856 – 1 January 1921) was a German politician who was chancellor of the German Empire, imperial chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry ...

acknowledged defeat, leading to the ''Rüstungswende'' or 'armaments turning point', when he switched expenditure from the navy to the army.

This decision was not driven by a reduction in political tensions but by German concern over Russia's quick recovery from its defeat in the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

and the subsequent

1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, th ...

. Economic reforms led to a significant post-1908 expansion of railways and transportation infrastructure, particularly in its western border regions. Since Germany and Austria-Hungary relied on faster mobilisation to compensate for their numerical inferiority compared to Russia, the threat posed by the closing of this gap was more important than competing with the Royal Navy. After Germany expanded its standing army by 170,000 troops in 1913, France extended compulsory military service from two to three years; similar measures were taken by the

Balkan powers and Italy, which led to increased expenditure by the

Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

and Austria-Hungary. Absolute figures are difficult to calculate due to differences in categorising expenditure since they often omit civilian infrastructure projects like railways which had logistical importance and military use. It is known, however, that from 1908 to 1913, military spending by the six major European powers increased by over 50% in real terms.

Conflicts in the Balkans

The years before 1914 were marked by a series of crises in the Balkans, as other powers sought to benefit from the Ottoman decline. While

Pan-Slavic

Pan-Slavism, a movement that took shape in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with promoting integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled the South S ...

and

Orthodox Russia considered itself the protector of

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and other

Slav

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and N ...

states, they preferred the strategically vital

Bosporus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

straits to be controlled by a weak Ottoman government, rather than an ambitious Slav power like

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

. Russia had ambitions in northeastern

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

while its clients had overlapping claims in the Balkans. These competing interests divided Russian policy-makers and added to regional instability.

Austrian statesmen viewed the Balkans as essential for the continued existence of their Empire and saw Serbian expansion as a direct threat. The 1908–1909

Bosnian Crisis

The Bosnian Crisis, also known as the Annexation Crisis (, ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Aneksiona kriza, Анексиона криза) or the First Balkan Crisis, erupted on 5 October 1908 when Austria-Hungary announced the annexation of Bosnia and Herzeg ...

began when Austria annexed the former Ottoman territory of

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, which it

had occupied since 1878. Timed to coincide with the

Bulgarian Declaration of Independence

The ''de jure'' independence of Bulgaria () from the Ottoman Empire was proclaimed on in the old capital of Tarnovo by Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria, who afterwards took the title "Tsar".

Background

Bulgaria had been a widely autonomous p ...

from the Ottoman Empire, this unilateral action was denounced by the European powers, but accepted as there was no consensus on how to resolve the situation. Some historians see this as a significant escalation, ending any chance of Austria cooperating with Russia in the Balkans, while also damaging diplomatic relations between Serbia and Italy.

Tensions increased after the 1911–1912

Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish (, "Tripolitanian War", , "War of Libya"), also known as the Turco-Italian War, was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911 to 18 October 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captur ...

demonstrated Ottoman weakness and led to the formation of the

Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which still ...

, an alliance of Serbia, Bulgaria,

Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, and

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. The League quickly overran most of the Ottomans' territory in the Balkans during the 1912–1913

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

, much to the surprise of outside observers. The Serbian capture of ports on the

Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

resulted in partial Austrian mobilisation, starting on 21 November 1912, including units along the Russian border in

Galicia. The

Russian government

The Russian Government () or fully titled the Government of the Russian Federation () is the highest federal executive governmental body of the Russian Federation. It is accountable to the president of the Russian Federation and controlled by ...

decided not to mobilise in response, unprepared to precipitate a war.

The Great Powers sought to re-assert control through the 1913

Treaty of London, which had created an independent

Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

while enlarging the territories of Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro and Greece. However, disputes between the victors sparked the 33-day

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia and Kingdom of Greece, Greece, on 1 ...

, when Bulgaria attacked Serbia and Greece on 16 June 1913; it was defeated, losing most of

Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

to Serbia and Greece, and

Southern Dobruja

Southern Dobruja or South Dobruja ( or simply , ; or , ), also the Quadrilateral (), is an area of north-eastern Bulgaria comprising Dobrich and Silistra provinces, part of the historical region of Dobruja. It has an area of 7,412 square km an ...

to Romania. The result was that even countries which benefited from the Balkan Wars, such as Serbia and Greece, felt cheated of their "rightful gains", while for Austria it demonstrated the apparent indifference with which other powers viewed their concerns, including Germany. This complex mix of resentment, nationalism and insecurity helps explain why the pre-1914 Balkans became known as the "

powder keg of Europe".

Prelude

Sarajevo assassination

On 28 June 1914,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassination in Sarajevo was the ...

, heir presumptive to Emperor

Franz Joseph I of Austria

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I ( ; ; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the ruler of the Grand title of the emperor of Austria, other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 1848 until his death ...

, visited

Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ), ; ''see Names of European cities in different languages (Q–T)#S, names in other languages'' is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 2 ...

, the capital of the recently annexed

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

.

Cvjetko Popović,

Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip ( sr-Cyrl, Гаврило Принцип, ; 25 July 189428 April 1918) was a Bosnian Serb student who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie, Duchess von ...

,

Nedeljko Čabrinović

Nedeljko Čabrinović ( sr-Cyrl, Недељко Чабриновић; 1 February 1895 – 23 January 1916) was a Bosnian Serb typesetter and political activist, known for his role in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 ...

,

Trifko Grabež,

Vaso Čubrilović

Vaso Čubrilović ( sr-Cyrl, Васо Чубриловић; 14 January 1897 – 11 June 1990) was a YugoslavВладимир Дедијер, ''Сарајево 1914'', Просвета, Београд 1966, стр. 568 and Bosnian Serb scholar an ...

(

Bosnian Serbs

The Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sr-Cyrl, Срби Босне и Херцеговине, Srbi Bosne i Hercegovine), often referred to as Bosnian Serbs ( sr-cyrl, босански Срби, bosanski Srbi) or Herzegovinian Serbs ( sr-cyrl, � ...

) and

Muhamed Mehmedbašić

Muhamed Mehmedbašić (1887 – 29 May 1943) was a Serbian revolutionary and the main planner in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which led to a sequence of events that resulted in the outbreak of World War I.

Early life

Mehmedbaš ...

(from the

Bosniaks

The Bosniaks (, Cyrillic script, Cyrillic: Бошњаци, ; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia (region), Bosnia, today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and who sha ...

community), from the movement known as

Young Bosnia

Young Bosnia ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Млада Босна, Mlada Bosna) refers to a loosely organised grouping of separatist and revolutionary cells active in the early 20th century, that sought to end the Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovin ...

, took up positions along the Archduke's motorcade route, to assassinate him. Supplied with arms by extremists within the Serbian

Black Hand intelligence organisation, they hoped his death would free Bosnia from Austrian rule.

Čabrinović threw a

grenade

A grenade is a small explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a Shell (projectile), shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A mod ...

at the Archduke's car and injured two of his aides. The other assassins were also unsuccessful. An hour later, as Ferdinand was returning from visiting the injured officers in hospital, his car took a wrong turn into a street where

Gavrilo Princip

Gavrilo Princip ( sr-Cyrl, Гаврило Принцип, ; 25 July 189428 April 1918) was a Bosnian Serb student who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie, Duchess von ...

was standing. He fired two pistol shots, fatally wounding Ferdinand and his wife

Sophie

Sophie is a feminine given name, another version of Sophia, from the Greek word for "wisdom".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Soph ...

.

According to historian

Zbyněk Zeman, in Vienna "the event almost failed to make any impression whatsoever. On 28 and 29 June, the crowds listened to music and drank wine, as if nothing had happened." Nevertheless, the impact of the murder of the heir to the throne was significant, and has been described by historian

Christopher Clark as a "9/11 effect, a terrorist event charged with historic meaning, transforming the political chemistry in Vienna".

Expansion of violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Austro-Hungarian authorities encouraged subsequent

anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo.

Violent actions against ethnic Serbs were also organised outside Sarajevo, in other cities in Austro-Hungarian-controlled Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia. Austro-Hungarian authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina imprisoned approximately 5,500 prominent Serbs, 700 to 2,200 of whom died in prison. A further 460 Serbs were sentenced to death. A predominantly Bosniak special militia known as the ''

Schutzkorps'' was established, and carried out the persecution of Serbs.

July Crisis

The assassination initiated the July Crisis, a month of diplomatic manoeuvring among Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France and Britain. Believing that Serbian intelligence helped organise Franz Ferdinand's murder, Austrian officials wanted to use the opportunity to end Serbian interference in Bosnia and saw war as the best way of achieving this. However, the

Foreign Ministry

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral re ...

had no solid proof of Serbian involvement. On 23July, Austria delivered an

ultimatum

An ; ; : ultimata or ultimatums) is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a coercion, threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance (open loop). An ultimatum is generally the ...

to Serbia, listing ten demands made intentionally unacceptable to provide an excuse for starting hostilities.

Serbia ordered general

mobilisation

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

on 25July, but accepted all the terms, except for those empowering Austrian representatives to suppress "subversive elements" inside Serbia, and take part in the investigation and trial of Serbians linked to the assassination. Claiming this amounted to rejection, Austria broke off diplomatic relations and ordered partial mobilisation the next day; on 28 July, they declared war on Serbia and began shelling

Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

. Russia ordered general mobilisation in support of Serbia on 30 July.

Anxious to ensure backing from the

SPD political opposition by presenting Russia as the aggressor, German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg delayed the commencement of war preparations until 31 July. That afternoon, the Russian government were handed a note requiring them to "cease all war measures against Germany and Austria-Hungary" within 12 hours. A further German demand for neutrality was refused by the French who ordered

general mobilisation but delayed declaring war. The

German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

had long assumed they faced a war on two fronts; the

Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan (, ) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on 4 August 1914. Schlieffe ...

envisaged using 80% of the army to defeat France, then switching to Russia. Since this required them to move quickly, mobilisation orders were issued that afternoon. Once the German ultimatum to Russia expired on the morning of 1 August, the two countries were at war.

At a meeting on 29 July, the British cabinet had narrowly decided its obligations to Belgium under the 1839

Treaty of London did not require it to oppose a German invasion with military force; however, Prime Minister

Asquith and his senior Cabinet ministers were already committed to supporting France, the Royal Navy had been mobilised, and public opinion was strongly in favour of intervention. On 31 July, Britain sent notes to Germany and France, asking them to respect Belgian neutrality; France pledged to do so, but Germany did not reply. Aware of German plans to attack through Belgium, French Commander-in-Chief

Joseph Joffre

Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre , (; 12 January 1852 – 3 January 1931) was a French general who served as Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front from the start of World War I until the end of 19 ...

asked his government for permission to cross the border and pre-empt such a move. To avoid violating Belgian neutrality, he was told any advance could come only after a German invasion. Instead, the French cabinet ordered its Army to withdraw 10 km behind the German frontier, to avoid provoking war. On 2 August,

Germany occupied Luxembourg and exchanged fire with French units when German patrols entered French territory; on 3August, they declared war on France and demanded free passage across Belgium, which was refused. Early on the morning of 4August, the Germans invaded, and

Albert I of Belgium

Albert I (8 April 1875 – 17 February 1934) was King of the Belgians from 23 December 1909 until his death in 1934. He is popularly referred to as the Knight King (, ) or Soldier King (, ) in Belgium in reference to his role during World War I ...

called for assistance under the

Treaty of London. Britain sent Germany an ultimatum demanding they withdraw from Belgium; when this expired at midnight, without a response, the two empires were at war.

Progress of the war

Opening hostilities

Confusion among the Central Powers

Germany promised to support Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia, but interpretations of what this meant differed. Previously tested deployment plans had been replaced early in 1914, but those had never been tested in exercises. Austro-Hungarian leaders believed Germany would cover its northern flank against Russia.

Serbian campaign

Beginning on 12 August, the Austrians and Serbs clashed at the battles of the

Cer and

Kolubara

The Kolubara ( sr-cyr, Колубара, ) is a long river in western Serbia; it is an eastern, right tributary to the Sava river.

Due to the many long tributaries creating a branchy system within the river's drainage basin, the short Kolubara ...

; over the next two weeks, Austrian attacks were repulsed with heavy losses. As a result, Austria had to keep sizeable forces on the Serbian front, weakening their efforts against Russia. Serbia's victory against Austria-Hungary in the 1914 invasion has been called one of the major upset victories of the twentieth century. In 1915, the campaign saw the first use of

anti-aircraft warfare

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface (Submarine#Armament, submarine-lau ...

after an Austrian plane was shot down with

ground-to-air fire, as well as the first

medical evacuation

Medical evacuation, often shortened to medevac or medivac, is the timely and efficient movement and en route care provided by medical personnel to patients requiring evacuation or transport using medically equipped air ambulances, helicopters and ...

by the Serbian army.

German offensive in Belgium and France

Upon mobilisation, in accordance with the

Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan (, ) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on 4 August 1914. Schlieffe ...

, 80% of the

German Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

was located on the Western Front, with the remainder acting as a screening force in the East. Rather than a direct attack across their shared frontier, the German right wing would sweep through the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

and

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, then swing south, encircling Paris and trapping the French army against the Swiss border. The plan's creator,

Alfred von Schlieffen

Graf Alfred von Schlieffen (; 28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913) was a German field marshal and strategist who served as chief of the Imperial German General Staff from 1891 to 1906. His name lived on in the 1905–06 " Schlieffen Plan", ...

, head of the

German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

from 1891 to 1906, estimated that this would take six weeks, after which the German army would transfer to the East and defeat the Russians.

The plan was substantially modified by his successor,

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger

Graf Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke (; 25 May 1848 – 18 June 1916), also known as Moltke the Younger, was a German general and Chief of the Great German General Staff, a member of the House of Moltke. He was also the nephew of '' Genera ...

. Under Schlieffen, 85% of German forces in the west were assigned to the right wing, with the remainder holding along the frontier. By keeping his left-wing deliberately weak, he hoped to lure the French into an offensive into the "lost provinces" of

Alsace-Lorraine, which was the strategy envisaged by their

Plan XVII

Plan XVII () was the name of a "scheme of mobilisation and concentration" which the French (the peacetime title of the French ) developed from 1912 to 1914, to be put into effect by the French Army in the event of war between France and Ger ...

. However, Moltke grew concerned that the French might push too hard on his left flank and as the German Army increased in size from 1908 to 1914, he changed the allocation of forces between the two wings to 70:30. He also considered Dutch neutrality essential for German trade and cancelled the incursion into the Netherlands, which meant any delays in Belgium threatened the viability of the plan. Historian

Richard Holmes argues that these changes meant the right wing was not strong enough to achieve decisive success.

The initial German advance in the West was very successful. By the end of August, the Allied left, which included the

British Expeditionary Force (BEF), was in

full retreat, and the French offensive in Alsace-Lorraine was a disastrous failure, with casualties exceeding 260,000. German planning provided broad strategic instructions while allowing army commanders considerable freedom in carrying them out at the front, but

Alexander von Kluck

Alexander Heinrich Rudolph von Kluck (20 May 1846 – 19 October 1934) was a German general during World War I.

Early life

Kluck was born in Münster, in Westphalia on 20 May 1846.

He was the son of architect Karl von Kluck and his wife Elisa ...

used this freedom to disobey orders, opening a gap between the German armies as they closed on Paris. The French army, reinforced by the British expeditionary corps, seized this opportunity to counter-attack and pushed the German army 40 to 80 km back. Both armies were then so exhausted that no decisive move could be implemented, so they settled in trenches, with the vain hope of breaking through as soon as they could build local superiority.

In 1911, the Russian

Stavka

The ''Stavka'' ( Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка, ) is a name of the high command of the armed forces used formerly in the Russian Empire and Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrat ...

agreed with the French to attack Germany within fifteen days of mobilisation, ten days before the Germans had anticipated, although it meant the two Russian armies that entered

East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

on 17 August did so without many of their support elements.

By the end of 1914, German troops held strong defensive positions inside France, controlled the bulk of France's domestic coalfields, and inflicted 230,000 more casualties than it lost itself. However, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance of a decisive outcome, while it had failed to achieve the primary objective of avoiding a long, two-front war. As was apparent to several German leaders, this amounted to a strategic defeat; shortly after the

First Battle of the Marne

The First Battle of the Marne or known in France as the Miracle on the Marne () was a battle of the First World War fought from the 5th to the 12th September 1914. The German army invaded France with a plan for winning the war in 40 days by oc ...

,

Crown Prince Wilhelm told an American reporter "We have lost the war. It will go on for a long time but lost it is already."

Asia and the Pacific

On 30 August 1914, New Zealand

occupied German Samoa (now

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

). On 11 September, the

Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force landed on the island of

New Britain

New Britain () is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi Island, Umboi the Dampie ...

, then part of

German New Guinea

German New Guinea () consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups, and was part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , became a German protectorate in 188 ...

. On 28 October, the German cruiser sank the

Russian cruiser ''Zhemchug'' in the

Battle of Penang. Japan declared war on Germany before seizing territories in the Pacific, which later became the

South Seas Mandate

The South Seas Mandate, officially the Mandate for the German Possessions in the Pacific Ocean Lying North of the Equator, was a League of Nations mandate in the " South Seas" given to the Empire of Japan by the League of Nations following W ...

, as well as German

Treaty ports

Treaty ports (; ) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China (before th ...

on the Chinese

Shandong

Shandong is a coastal Provinces of China, province in East China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River. It has served as a pivotal cultural ...

peninsula at

Tsingtao. After Vienna refused to withdraw its cruiser from Tsingtao, Japan declared war on Austria-Hungary, and the ship was sunk in November 1914. Within a few months, Allied forces had seized all German territories in the Pacific, leaving only isolated commerce raiders and a few holdouts in New Guinea.

African campaigns

Some of the first clashes of the war involved British, French, and German colonial forces in Africa. On 6–7 August, French and British troops invaded the German protectorates of

Togoland

Togoland, officially the Togoland Protectorate (; ), was a protectorate of the German Empire in West Africa from 1884 to 1914, encompassing what is now the nation of Togo and most of what is now the Volta Region of Ghana, approximately 90,400&nb ...

and

Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern ...

. On 10 August, German forces in

South-West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990.

South West Africa bordered Angola ( a Portu ...

attacked South Africa; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the rest of the war. The German colonial forces in

German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

, led by Colonel

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck (20 March 1870 – 9 March 1964), popularly known as the Lion of Africa (), was a general in the Imperial German Army and the commander of its forces in the German East Africa campaign. For four years, with a force ...

, fought a

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

campaign and only surrendered two weeks after the armistice took effect in Europe.

Indian support for the Allies

Before the war, Germany had attempted to use Indian nationalism and pan-Islamism to its advantage, a policy continued post-1914 by

instigating uprisings in India, while the

Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition urged Afghanistan to join the war on the side of Central Powers. However, contrary to British fears of a revolt in India, the outbreak of the war saw a reduction in nationalist activity. Leaders from the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

and other groups believed support for the British war effort would hasten

Indian Home Rule, a promise allegedly made explicit in 1917 by

Edwin Montagu

Edwin Samuel Montagu PC (6 February 1879 – 15 November 1924) was a British Liberal politician who served as Secretary of State for India between 1917 and 1922. Montagu was a "radical" Liberal and the third practising Jew (after Sir Herber ...

, the

Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India secretary or the Indian secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of ...

.

In 1914, the

British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

was larger than the British Army itself, and between 1914 and 1918 an estimated 1.3 million Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. In all, 140,000 soldiers served on the Western Front and nearly 700,000 in the Middle East, with 47,746 killed and 65,126 wounded. The suffering engendered by the war, as well as the failure of the British government to grant self-government to India afterward, bred disillusionment, resulting in

the campaign for full independence led by

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

.

Western Front

Trench warfare begins

Pre-war military tactics that had emphasised open warfare and individual riflemen proved obsolete when confronted with conditions prevailing in 1914. Technological advances allowed the creation of strong defensive systems largely impervious to massed infantry advances, such as

barbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire or bob wire (in the Southern and Southwestern United States), is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the ...

, machine guns and above all far more powerful

artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

, which dominated the battlefield and made crossing open ground extremely difficult. Both sides struggled to develop tactics for breaching entrenched positions without heavy casualties. In time, technology enabled the production of new offensive weapons, such as

gas warfare and the

tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

.

After the

First Battle of the Marne

The First Battle of the Marne or known in France as the Miracle on the Marne () was a battle of the First World War fought from the 5th to the 12th September 1914. The German army invaded France with a plan for winning the war in 40 days by oc ...

in September 1914, Allied and German forces unsuccessfully tried to outflank each other, a series of manoeuvres later known as the "Race to the Sea". By the end of 1914, the opposing forces confronted each other along an uninterrupted line of entrenched positions from the English Channel, Channel to the Swiss border. Since the Germans were normally able to choose where to stand, they generally held the high ground, while their trenches tended to be better built; those constructed by the French and English were initially considered "temporary", only needed until an offensive would destroy the German defences. Both sides tried to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. On 22 April 1915, at the Second Battle of Ypres, the Germans (violating the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, Hague Convention) used chlorine gas for the first time on the Western Front. Several types of gas soon became widely used by both sides and though it never proved a decisive, battle-winning weapon, it became one of the most feared and best-remembered horrors of the war.

Continuation of trench warfare

In February 1916, the Germans attacked French defensive positions at the Battle of Verdun, lasting until December 1916. Casualties were greater for the French, but the Germans bled heavily as well, with anywhere from 700,000 to 975,000 casualties between the two combatants. Verdun became a symbol of French determination and self-sacrifice.

The Battle of the Somme was an Anglo-French offensive from July to November 1916. The first day on the Somme, opening day, on 1 July 1916, was the bloodiest single day in the history of the British Army, which suffered 57,500 casualties, including 19,200 dead. As a whole, the Somme offensive led to an estimated 420,000 British casualties, along with 200,000 French and 500,000 Germans. The diseases that emerged in the trenches were a major killer on both sides. The living conditions led to disease and infection, such as trench foot, louse, lice, typhus, trench fever, and the '

Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest docum ...

'.

Naval war

At the start of the war, German cruisers were scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied merchant shipping. These were systematically hunted down by the Royal Navy, though not before causing considerable damage. One of the most successful was the , part of the German East Asia Squadron stationed at Qingdao, which seized or sank 15 merchantmen, a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. Most of the squadron was returning to Germany when it sank two British armoured cruisers at the Battle of Coronel in November 1914, before being virtually destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December. The SMS Dresden (1907), SMS ''Dresden'' escaped with a few auxiliaries, but after the Battle of Más a Tierra, these too were either destroyed or interned.

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Britain began a naval Blockade of Germany (1914–1919), blockade of Germany. This proved effective in cutting off vital supplies, though it violated accepted international law. Britain also mined international waters which closed off entire sections of the ocean, even to neutral ships. Since there was limited response to this tactic, Germany expected a similar response to its unrestricted submarine warfare.

The Battle of Jutland in May/June 1916 was the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war, and one of the largest in history. The clash was indecisive, though the Germans inflicted more damage than they received; thereafter the bulk of the German High Seas Fleet was confined to port.

German U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Britain.

The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival.

The United States launched a protest, and Germany changed its rules of engagement. After Sinking of the RMS Lusitania, the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania, RMS ''Lusitania'' in 1915, Germany promised not to target passenger liners, while Britain armed its merchant ships, placing them beyond the protection of the "Prize (law), cruiser rules", which demanded warning and movement of crews to "a place of safety" (a standard that lifeboats did not meet). Finally, in early 1917, Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realising the Americans would eventually enter the war.

Germany sought to strangle Allied sea lanes before the United States could transport a large army overseas, but, after initial successes, eventually failed to do so.

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships began travelling in Convoys in World War I, convoys, escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the hydrophone and depth charges were introduced, destroyers could potentially successfully attack a submerged submarine. Convoys slowed the flow of supplies since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled; the solution was an extensive program of building new freighters. Troopships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys. The U-boats sunk more than 5,000 Allied ships, at the cost of 199 submarines.

World War I also saw the first use of aircraft carriers in combat, with launching Sopwith Camels in a successful raid against the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern raid, Tondern in July 1918, as well as blimps for antisubmarine patrol.

Southern theatres

War in the Balkans

Faced with Russia in the east, Austria-Hungary could spare only one-third of its army to attack Serbia. After suffering heavy losses, the Austrians briefly occupied the Serbian capital,

Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

. A Serbian counter-attack in the Battle of Kolubara succeeded in driving them from the country by the end of 1914. For the first 10 months of 1915, Austria-Hungary used most of its military reserves to fight Italy. German and Austro-Hungarian diplomats scored a coup by persuading Bulgaria to join the attack on Serbia. The Austro-Hungarian provinces of Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia (region), Bosnia provided troops for Austria-Hungary. Montenegro allied itself with Serbia.

Bulgaria declared war on Serbia on 14 October 1915, and joined in the attack by the Austro-Hungarian army under Mackensen's army of 250,000 that was already underway. Serbia was conquered in a little more than a month, as the Central Powers, now including Bulgaria, sent in 600,000 troops in total. The Serbian army, fighting on two fronts and facing certain defeat, retreated into northern Principality of Albania, Albania. The Serbs suffered defeat in the Kosovo offensive (1915), Battle of Kosovo. Montenegro covered the Serbian retreat toward the Adriatic coast in the Battle of Mojkovac on 6–7 January 1916, but ultimately the Austrians also conquered Montenegro. The surviving Serbian soldiers were evacuated to Greece. After the conquest, Serbia was divided between Austro-Hungary and Bulgaria.

In late 1915, a Franco-British force landed at Thessaloniki, Salonica in Greece to offer assistance and to pressure its government to declare war against the Central Powers. However, the pro-German Constantine I of Greece, King Constantine I dismissed the pro-Allied government of Eleftherios Venizelos before the Allied expeditionary force arrived.

The Macedonian front was at first mostly static. French and Serbian forces retook limited areas of Macedonia by recapturing Bitola on 19 November 1916, following the costly Monastir offensive, which brought stabilisation of the front.

Serbian and French troops finally made a breakthrough in September 1918 in the Vardar offensive, after most German and Austro-Hungarian troops had been withdrawn. The Bulgarians were defeated at the Battle of Dobro Pole, and by 25 September British and French troops had crossed the border into Bulgaria proper as the Bulgarian army collapsed. Bulgaria capitulated four days later, on 29 September 1918. The German high command responded by despatching troops to hold the line, but these forces were too weak to re-establish a front.

The Allied breakthrough on the Macedonian front cut communications between the Ottoman Empire and the other

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

, and made Vienna vulnerable to attack. Hindenburg and Ludendorff concluded that the strategic and operational balance had now shifted decidedly against the

Central Powers