Versailles Treaty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Versailles was a

During the autumn of 1918, the Central Powers began to collapse. Desertion rates within the German army began to increase, and civilian strikes drastically reduced war production. On the Western Front, the Allied forces launched the Hundred Days Offensive and decisively defeated the German western armies. Sailors of the Imperial German Navy at Kiel mutinied in response to the naval order of 24 October 1918, which prompted uprisings in Germany, which became known as the

During the autumn of 1918, the Central Powers began to collapse. Desertion rates within the German army began to increase, and civilian strikes drastically reduced war production. On the Western Front, the Allied forces launched the Hundred Days Offensive and decisively defeated the German western armies. Sailors of the Imperial German Navy at Kiel mutinied in response to the naval order of 24 October 1918, which prompted uprisings in Germany, which became known as the

Talks between the Allies to establish a common negotiating position started on 18 January 1919, in the (Clock Room) at the French Foreign Ministry on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris.

Initially, 70 delegates from 27 nations participated in the negotiations.

Talks between the Allies to establish a common negotiating position started on 18 January 1919, in the (Clock Room) at the French Foreign Ministry on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris.

Initially, 70 delegates from 27 nations participated in the negotiations.

Britain had suffered heavy financial costs but suffered little physical devastation during the war. British public opinion wanted to make Germany pay for the War.

Public opinion favoured a "just peace", which would force Germany to pay reparations and be unable to repeat the aggression of 1914, although those of a "liberal and advanced opinion" shared Wilson's ideal of a peace of reconciliation.

In private Lloyd George opposed revenge and attempted to compromise between Clemenceau's demands and the Fourteen Points, because Europe would eventually have to reconcile with Germany.

Lloyd George wanted terms of reparation that would not cripple the German economy, so that Germany would remain a viable economic power and trading partner. By arguing that British war pensions and widows' allowances should be included in the German reparation sum, Lloyd George ensured that a large amount would go to the British Empire.

Lloyd George also intended to maintain a European balance of power to thwart a French attempt to establish itself as the dominant European power. A revived Germany would be a counterweight to France and a deterrent to Bolshevik Russia. Lloyd George also wanted to neutralize the German navy to keep the

Britain had suffered heavy financial costs but suffered little physical devastation during the war. British public opinion wanted to make Germany pay for the War.

Public opinion favoured a "just peace", which would force Germany to pay reparations and be unable to repeat the aggression of 1914, although those of a "liberal and advanced opinion" shared Wilson's ideal of a peace of reconciliation.

In private Lloyd George opposed revenge and attempted to compromise between Clemenceau's demands and the Fourteen Points, because Europe would eventually have to reconcile with Germany.

Lloyd George wanted terms of reparation that would not cripple the German economy, so that Germany would remain a viable economic power and trading partner. By arguing that British war pensions and widows' allowances should be included in the German reparation sum, Lloyd George ensured that a large amount would go to the British Empire.

Lloyd George also intended to maintain a European balance of power to thwart a French attempt to establish itself as the dominant European power. A revived Germany would be a counterweight to France and a deterrent to Bolshevik Russia. Lloyd George also wanted to neutralize the German navy to keep the

The treaty stripped Germany of of territory and 7 million people. It also required Germany to give up the gains made via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and grant independence to the protectorates that had been established.

In

The treaty stripped Germany of of territory and 7 million people. It also required Germany to give up the gains made via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and grant independence to the protectorates that had been established.

In

Article 119 of the treaty required Germany to renounce sovereignty over former colonies and Article 22 converted the territories into League of Nations mandates under the control of Allied states. Article 22 and Article 119 Togoland and

Article 119 of the treaty required Germany to renounce sovereignty over former colonies and Article 22 converted the territories into League of Nations mandates under the control of Allied states. Article 22 and Article 119 Togoland and

To ensure compliance, the Rhineland and bridgeheads east of the Rhine were to be occupied by Allied troops for fifteen years. Article 428

If Germany had not committed aggression, a staged withdrawal would take place; after five years, the

To ensure compliance, the Rhineland and bridgeheads east of the Rhine were to be occupied by Allied troops for fifteen years. Article 428

If Germany had not committed aggression, a staged withdrawal would take place; after five years, the

The delegates of the Commonwealth and British Government had mixed thoughts on the treaty, with some seeing the French policy as being greedy and vindictive. Lloyd George and his private secretary Philip Kerr believed in the treaty, although they also felt that the French would keep Europe in a constant state of turmoil by attempting to enforce the treaty. Delegate Harold Nicolson wrote "are we making a good peace?", while General Jan Smuts (a member of the South African delegation) wrote to Lloyd-George, before the signing, that the treaty was unstable and declared "Are we in our sober senses or suffering from shellshock? What has become of Wilson's 14 points?" He wanted the Germans not be made to sign at the "point of the bayonet".

Smuts issued a statement condemning the treaty and regretting that the promises of "a new international order and a fairer, better world are not written in this treaty". Lord Robert Cecil said that many within the

The delegates of the Commonwealth and British Government had mixed thoughts on the treaty, with some seeing the French policy as being greedy and vindictive. Lloyd George and his private secretary Philip Kerr believed in the treaty, although they also felt that the French would keep Europe in a constant state of turmoil by attempting to enforce the treaty. Delegate Harold Nicolson wrote "are we making a good peace?", while General Jan Smuts (a member of the South African delegation) wrote to Lloyd-George, before the signing, that the treaty was unstable and declared "Are we in our sober senses or suffering from shellshock? What has become of Wilson's 14 points?" He wanted the Germans not be made to sign at the "point of the bayonet".

Smuts issued a statement condemning the treaty and regretting that the promises of "a new international order and a fairer, better world are not written in this treaty". Lord Robert Cecil said that many within the

After the Versailles conference, Democratic President Woodrow Wilson claimed that "at last the world knows America as the savior of the world!" However, Wilson had refused to bring any leading members of the Republican party, led by Henry Cabot Lodge, into the talks. The Republicans controlled the

After the Versailles conference, Democratic President Woodrow Wilson claimed that "at last the world knows America as the savior of the world!" However, Wilson had refused to bring any leading members of the Republican party, led by Henry Cabot Lodge, into the talks. The Republicans controlled the

After Scheidemann's resignation, a new coalition government was formed under Gustav Bauer. President

After Scheidemann's resignation, a new coalition government was formed under Gustav Bauer. President

Despite "hang the Kaiser" being a popular slogan of the time, particularly in Britain, the proposed trial of the Kaiser under Article 227 of the Versailles treaty never took place. Defying popular British anger at the Kaiser, and the fact that putting the Kaiser on trial was originally a British proposal, Lloyd George refused to support French calls for the Kaiser to be extradited from the Netherlands where he was living in exile. The Dutch authorities refused extradition, and the former Kaiser died there in 1941.

Article 228 allowed for the extradition of German war criminals to stand trial before Allied tribunals. Originally a list of as many of 20,000 alleged criminals was prepared by the Allies, however this was later reduced. Following the ratification of the treaty in January 1920, the Allies submitted a request that 890 (or 895) alleged war criminals be extradited for trial. France and Belgium each requested the extradition of 334 individuals including von Hindenburg and Ludendorff for the damages they had inflicted on Belgium and the mass deportations they had overseen from both France and Belgium. Britain submitted a list of 94 names, including von Tirpitz for the sinkings of civilian shipping by German U-boats. Italy's request included 29 names divided between those accused of mistreating prisoners of war and those responsible for U-Boat sinkings. Romania requested the extradition of 41 individuals including von Mackensen. Poland requested 51 people be extradited, and Yugoslavia (successor to wartime Serbia) four. Germany refused extradition, however, claiming that carrying out such a request to extradite people widely regarded as heroes in Germany would likely result in the fall of the government, but made a counter-offer of holding trials at Leipzig, an offer that was ultimately accepted by the Allies.

After subsequent negotiation, the list of alleged war criminals submitted by the Allies for trial at Leipzig was reduced to 45, however, this ultimately also ended up being too many for the German authorities, and in the end only 12 officers were put on trial – six from the British list, five from the French one, and one from the Belgian list. The British list included only low-level officers and enlisted men, including a prison-guard accused of beating prisoners of war and two U-Boat commanders who sank hospital ships (the

Despite "hang the Kaiser" being a popular slogan of the time, particularly in Britain, the proposed trial of the Kaiser under Article 227 of the Versailles treaty never took place. Defying popular British anger at the Kaiser, and the fact that putting the Kaiser on trial was originally a British proposal, Lloyd George refused to support French calls for the Kaiser to be extradited from the Netherlands where he was living in exile. The Dutch authorities refused extradition, and the former Kaiser died there in 1941.

Article 228 allowed for the extradition of German war criminals to stand trial before Allied tribunals. Originally a list of as many of 20,000 alleged criminals was prepared by the Allies, however this was later reduced. Following the ratification of the treaty in January 1920, the Allies submitted a request that 890 (or 895) alleged war criminals be extradited for trial. France and Belgium each requested the extradition of 334 individuals including von Hindenburg and Ludendorff for the damages they had inflicted on Belgium and the mass deportations they had overseen from both France and Belgium. Britain submitted a list of 94 names, including von Tirpitz for the sinkings of civilian shipping by German U-boats. Italy's request included 29 names divided between those accused of mistreating prisoners of war and those responsible for U-Boat sinkings. Romania requested the extradition of 41 individuals including von Mackensen. Poland requested 51 people be extradited, and Yugoslavia (successor to wartime Serbia) four. Germany refused extradition, however, claiming that carrying out such a request to extradite people widely regarded as heroes in Germany would likely result in the fall of the government, but made a counter-offer of holding trials at Leipzig, an offer that was ultimately accepted by the Allies.

After subsequent negotiation, the list of alleged war criminals submitted by the Allies for trial at Leipzig was reduced to 45, however, this ultimately also ended up being too many for the German authorities, and in the end only 12 officers were put on trial – six from the British list, five from the French one, and one from the Belgian list. The British list included only low-level officers and enlisted men, including a prison-guard accused of beating prisoners of war and two U-Boat commanders who sank hospital ships (the

Historians are split on the impact of the treaty. Some saw it as a good solution in a difficult time, others saw it as a disastrous measure that would anger the Germans to seek revenge. The actual impact of the treaty is also disputed.

In his book '' The Economic Consequences of the Peace'', John Maynard Keynes referred to the Treaty of Versailles as a " Carthaginian peace", a misguided attempt to destroy Germany on behalf of French

Historians are split on the impact of the treaty. Some saw it as a good solution in a difficult time, others saw it as a disastrous measure that would anger the Germans to seek revenge. The actual impact of the treaty is also disputed.

In his book '' The Economic Consequences of the Peace'', John Maynard Keynes referred to the Treaty of Versailles as a " Carthaginian peace", a misguided attempt to destroy Germany on behalf of French  French economist Étienne Mantoux disputed that analysis. During the 1940s, Mantoux wrote a posthumously published book titled ''The Carthaginian Peace, or the Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes'' in an attempt to rebut Keynes' claims. More recently economists have argued that the restriction of Germany to a small army saved it so much money it could afford the reparations payments.

It has been argued—for instance by historian

French economist Étienne Mantoux disputed that analysis. During the 1940s, Mantoux wrote a posthumously published book titled ''The Carthaginian Peace, or the Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes'' in an attempt to rebut Keynes' claims. More recently economists have argued that the restriction of Germany to a small army saved it so much money it could afford the reparations payments.

It has been argued—for instance by historian

The Treaty of Versailles resulted in the creation of several thousand miles of new boundaries, with maps playing a central role in the negotiations at Paris. The plebiscites initiated due to the treaty have drawn much comment. Historian Robert Peckham wrote that the issue of Schleswig "was premised on a gross simplification of the region's history. ... Versailles ignored any possibility of there being a third way: the kind of compact represented by the Swiss Federation; a bilingual or even trilingual Schleswig-Holsteinian state" or other options such as "a Schleswigian state in a loose confederation with Denmark or Germany, or an autonomous region under the protection of the League of Nations."

In regard to the East Prussia plebiscite, historian Richard Blanke wrote that "no other contested ethnic group has ever, under un-coerced conditions, issued so one-sided a statement of its national preference". Richard Debo wrote "both Berlin and Warsaw believed the

The Treaty of Versailles resulted in the creation of several thousand miles of new boundaries, with maps playing a central role in the negotiations at Paris. The plebiscites initiated due to the treaty have drawn much comment. Historian Robert Peckham wrote that the issue of Schleswig "was premised on a gross simplification of the region's history. ... Versailles ignored any possibility of there being a third way: the kind of compact represented by the Swiss Federation; a bilingual or even trilingual Schleswig-Holsteinian state" or other options such as "a Schleswigian state in a loose confederation with Denmark or Germany, or an autonomous region under the protection of the League of Nations."

In regard to the East Prussia plebiscite, historian Richard Blanke wrote that "no other contested ethnic group has ever, under un-coerced conditions, issued so one-sided a statement of its national preference". Richard Debo wrote "both Berlin and Warsaw believed the

online

* ** Also published as * * * *

Documents relating to the Treaty from the Parliamentary Collections

from the Library of Congress

The consequences of the Treaty of Versailles for today's world

* ttps://www.imdb.com/title/tt0441912/ ''My 1919'' – A film from the Chinese point of view, the only country that did not sign the treaty

"Versailles Revisted"

(Review of Manfred Boemeke, Gerald Feldman and Elisabeth Glaser

''The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment after 75 Years''

Cambridge, UK: German Historical Institute, Washington, and Cambridge University Press, 1998), ''Strategic Studies'' 9:2 (Spring 2000), 191–205

Map of Europe and the impact of the Versailles Treaty

at omniatlas.com * The Signing of the Peace Treaty, silent film (Youtube Premium)

''Link''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Versailles, Treaty Of 1919 in France June 1919 Arms control treaties Articles containing video clips France–Germany relations Germany–Italy relations Germany–Japan relations Germany–United Kingdom relations Germany–United States relations International relations

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually country, countries or governments, which formally ends a declaration of war, state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an ag ...

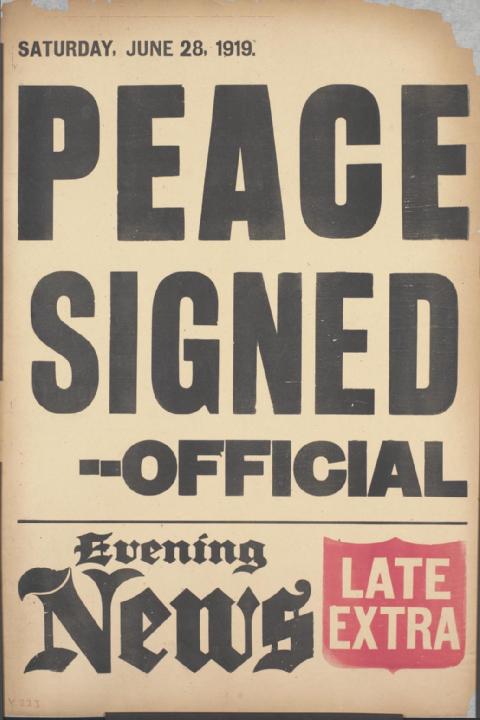

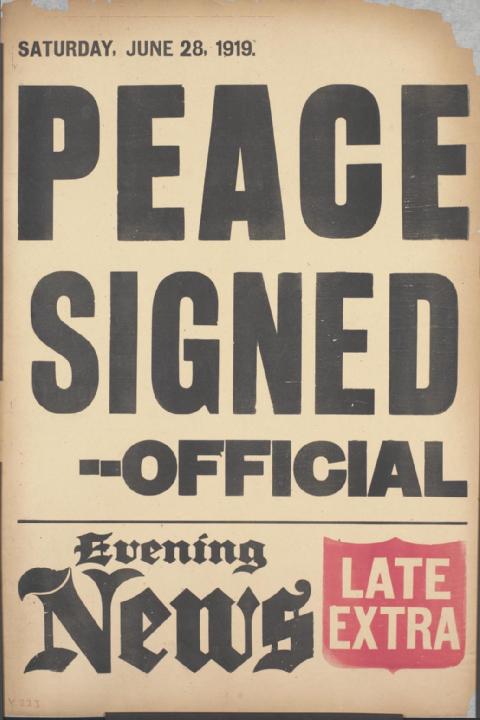

signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was one of the key events that led to World War I. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg ...

, which led to the war. The other Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

on the German side signed separate treaties. Although the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

of 11 November 1918 ended the actual fighting, and agreed certain principles and conditions including the payment of reparations, it took six months of Allied negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty. Germany was not allowed to participate in the negotiations before signing the treaty.

The treaty required Germany to disarm, make territorial concessions, extradite alleged war criminals, agree to Kaiser Wilhelm being put on trial, recognise the independence of states whose territory had previously been part of the German Empire, and pay reparations to the Entente powers. The most critical and controversial provision in the treaty was: "The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies." The other members of the Central Powers signed treaties containing similar articles. This article, Article 231, became known as the "War Guilt" clause.

Critics including John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

declared the treaty too harsh, styling it as a " Carthaginian peace", and saying the reparations were excessive and counterproductive. On the other hand, prominent Allied figures such as French Marshal Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general, Marshal of France and a member of the Académie Française and French Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences. He distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander ...

criticized the treaty for treating Germany too leniently. This is still the subject of ongoing debate by historians and economists.

The result of these competing and sometimes conflicting goals among the victors was a compromise that left no one satisfied. In particular, Germany was neither pacified nor conciliated, nor was it permanently weakened. The United States never ratified the Versailles treaty; instead it made a separate peace treaty with Germany, albeit based on the Versailles treaty. The problems that arose from the treaty would lead to the Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties, known collectively as the Locarno Pact, were seven post-World War I agreements negotiated amongst Germany, France, Great Britain, Belgium, Italy, Second Polish Republic, Poland and First Czechoslovak Republic, Czechoslovak ...

, which improved relations between Germany and the other European powers. The reparation system was reorganized and payments reduced in the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan temporarily resolved the issue of the reparations that Germany owed to the Allies of World War I. Enacted in 1924, it ended the crisis in European diplomacy that occurred after French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr in re ...

and the Young Plan. Bitter resentment of the treaty powered the rise of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

, and eventually the outbreak of a second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Although it is often referred to as the "Versailles Conference", only the actual signing of the treaty took place at the historic palace. Most of the negotiations were in Paris, with the "Big Four" meetings taking place generally at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

on the Quai d'Orsay.

Background

First World War

War broke out following theJuly Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the Great power, major powers of Europe in mid-1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I. It began on 28 June 1914 when the Serbs ...

in 1914. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, followed quickly by Germany declaring war on Russia on 1 August, and on Belgium and France on 3 August. The German invasion of Belgium on 3 August led to a declaration of war by Britain on Germany on 4 August, creating the conflict that became the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Two alliances faced off, the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

(led by Germany) and the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

(led by Britain, France and Russia). Other countries entered as fighting raged widely across Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, as well as the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

. Having seen the overthrow of the Tsarist regime in the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

and the Kerensky government in the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

under Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

in March 1918 signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

, amounting to a surrender that was highly favourable to Germany. Sensing victory before the American Expeditionary Forces could be ready, Germany now shifted forces to the Western Front and tried to overwhelm the Allies. It failed. Instead, the Allies won decisively on the battlefield, overwhelmed Germany's Turkish, Austrian, and Bulgarian allies, and forced an armistice in November 1918 that resembled a surrender.

Role of the Fourteen Points

The United States entered the war against the Central Powers in 1917 and PresidentWoodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

played a significant role in shaping the peace terms. His expressed aim was to detach the war from nationalistic disputes and ambitions. On 8 January 1918, Wilson issued the Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

. They outlined a policy of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

, open agreements, and democracy. While the term was not used, self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

was assumed. It called for a negotiated end to the war, international disarmament, the withdrawal of the Central Powers from occupied territories, the creation of a Polish state, the redrawing of Europe's borders along ethnic lines, and the formation of a League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

to guarantee the political independence and territorial integrity of all states. President Wilson's "Fourteen Points" Speech

It called for what it characterised as a just and democratic peace uncompromised by territorial annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

. The Fourteen Points were based on the research of the Inquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ...

, a team of about 150 advisors led by foreign-policy advisor Edward M. House, into the topics likely to arise in the expected peace conference.

Armistice

During the autumn of 1918, the Central Powers began to collapse. Desertion rates within the German army began to increase, and civilian strikes drastically reduced war production. On the Western Front, the Allied forces launched the Hundred Days Offensive and decisively defeated the German western armies. Sailors of the Imperial German Navy at Kiel mutinied in response to the naval order of 24 October 1918, which prompted uprisings in Germany, which became known as the

During the autumn of 1918, the Central Powers began to collapse. Desertion rates within the German army began to increase, and civilian strikes drastically reduced war production. On the Western Front, the Allied forces launched the Hundred Days Offensive and decisively defeated the German western armies. Sailors of the Imperial German Navy at Kiel mutinied in response to the naval order of 24 October 1918, which prompted uprisings in Germany, which became known as the German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

. The German government tried to obtain a peace settlement based on the Fourteen Points, and maintained it was on this basis that they surrendered. Following negotiations, the Allied powers and Germany signed an armistice, which came into effect on 11 November while German forces were still positioned in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

.

Many aspects of the Versailles treaty that were later criticised were agreed first in the 11 November armistice agreement, whilst the war was still ongoing. These included the German evacuation of German-occupied France, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

, Alsace-Lorraine, and the left bank of the Rhine (all of which were to be administered by the Allies under the armistice agreement), the surrender of a large quantity of war materiel, and the agreed payment of "reparation for damage done".

German forces evacuated occupied France, Belgium, and Luxembourg within the fifteen days required by the armistice agreement. By late 1918, Allied troops had entered Germany and began the occupation of the Rhineland under the agreement, in the process establishing bridgeheads across the Rhine in case of renewed fighting at Cologne, Koblenz, and Mainz. Allied and German forces were additionally to be separated by a 10 km-wide demilitarised zone.

Blockade

Both Germany and Great Britain were dependent on imports of food and raw materials, most of which had to be shipped across theAtlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

. The Blockade of Germany was a naval operation conducted by the Allied Powers to stop the supply of raw materials and foodstuffs reaching the Central Powers. The German was mainly restricted to the German Bight and used commerce raiders and unrestricted submarine warfare for a counter-blockade. The German Board of Public Health in December 1918 stated that civilians had died during the Allied blockade, although an academic study in 1928 put the death toll at

The blockade was maintained for eight months after the Armistice in November 1918, into the following year of 1919. Foodstuffs imports into Germany were controlled by the Allies after the Armistice with Germany until Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919. In March 1919, Churchill informed the House of Commons, that the ongoing blockade was a success and "Germany is very near starvation." From January 1919 to March 1919, Germany refused to agree to Allied demands that Germany surrender its merchant ships to Allied ports to transport food supplies. Some Germans considered the armistice to be a temporary cessation of the war and knew, if fighting broke out again, their ships would be seized. Over the winter of 1919, the situation became desperate and Germany finally agreed to surrender its fleet in March. The Allies then allowed for the import of 270,000 tons of foodstuffs.

Both German and non-German observers have argued that these were the most devastating months of the blockade for German civilians, though disagreement persists as to the extent and who is truly at fault. According to Max Rubner 100,000 German civilians died due to the continuation blockade after the armistice. In the UK, Labour Party member and anti-war activist Robert Smillie issued a statement in June 1919 condemning continuation of the blockade, claiming 100,000 German civilians had died as a result.

Negotiations

Talks between the Allies to establish a common negotiating position started on 18 January 1919, in the (Clock Room) at the French Foreign Ministry on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris.

Initially, 70 delegates from 27 nations participated in the negotiations.

Talks between the Allies to establish a common negotiating position started on 18 January 1919, in the (Clock Room) at the French Foreign Ministry on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris.

Initially, 70 delegates from 27 nations participated in the negotiations. Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

was excluded due to their signing of a separate peace (the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

) and early withdrawal from the war. Furthermore, German negotiators were excluded to deny them an opportunity to divide the Allies diplomatically.

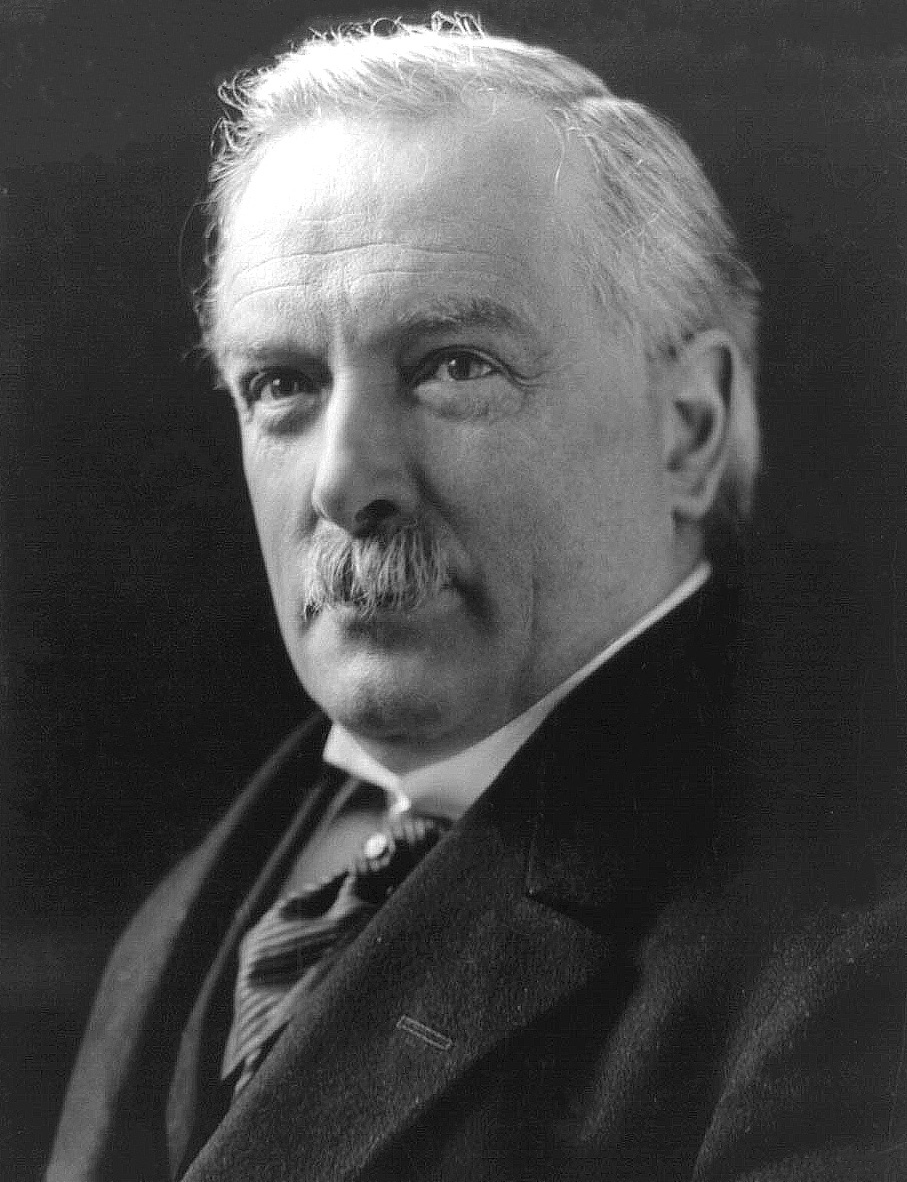

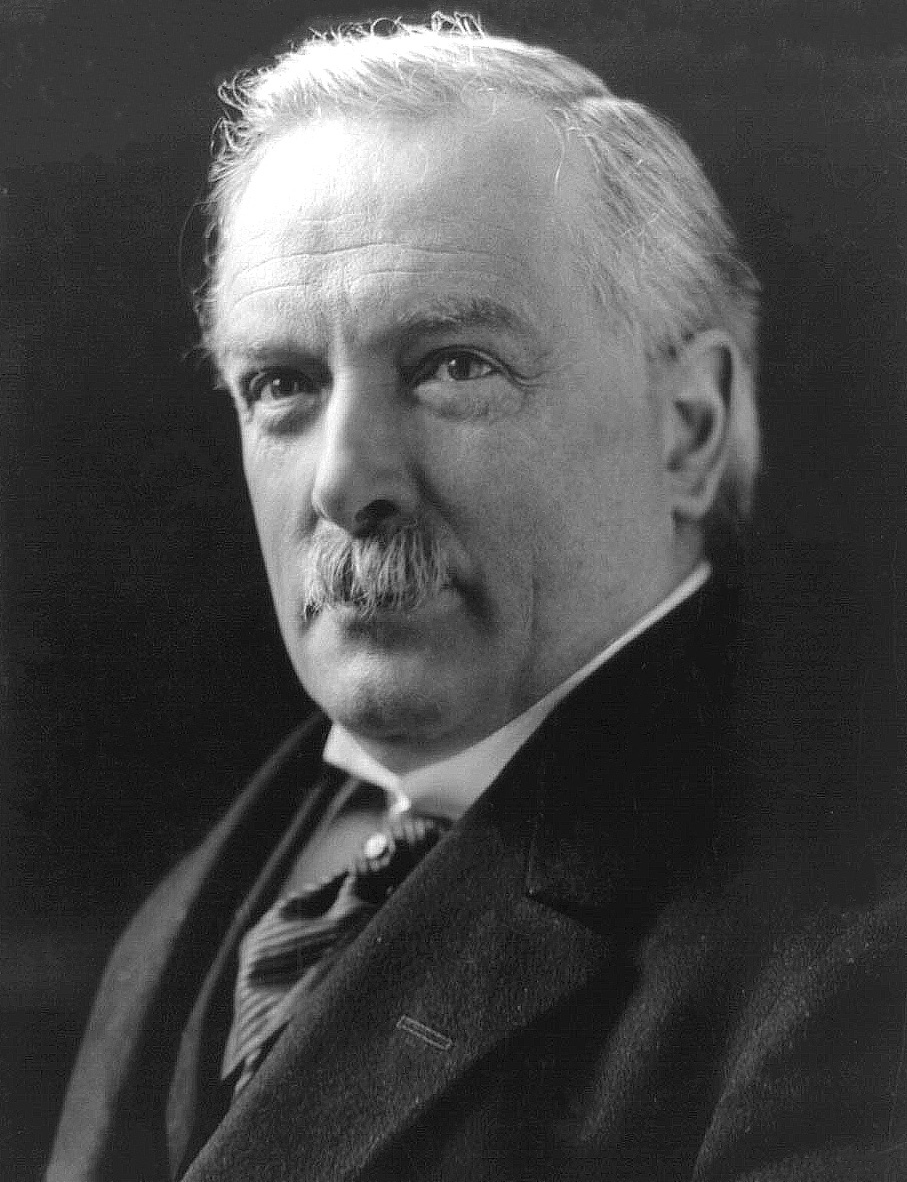

Initially, a "Council of Ten" (comprising two delegates each from Britain, France, the United States, Italy, and Japan) met officially to decide the peace terms. This council was replaced by the "Council of Five", formed from each country's foreign ministers, to discuss minor matters. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, and United States President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

formed the " Big Four" (at one point becoming the "Big Three" following the temporary withdrawal of Orlando). These four men met in 145 closed sessions to make all the major decisions, which were later ratified by the entire assembly. The minor powers attended a weekly "Plenary Conference" that discussed issues in a general forum but made no decisions. These members formed over 50 commissions that made various recommendations, many of which were incorporated into the final text of the treaty.

French aims

France had lost 1.3 million soldiers, including French men aged France had also been more physically damaged than any other nation; the so-called zone rouge (Red Zone), the most industrialized region and the source of most coal and iron ore in the north-east, had been devastated, and in the final days of the war, mines had been flooded and railways, bridges and factories destroyed. Clemenceau intended to ensure the security of France, by weakening Germany economically, militarily, territorially and by supplanting Germany as the leading producer of steel in Europe. British economist and Versailles negotiatorJohn Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

summarized this position as attempting to "set the clock back and undo what, since 1870, the progress of Germany had accomplished."

Clemenceau told Wilson: "America is far away, protected by the ocean. Not even Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

himself could touch England. You are both sheltered; we are not".

The French wanted a frontier on the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

, to protect France from a German invasion and compensate for French demographic and economic inferiority.

American and British representatives refused the French claim and after two months of negotiations, the French accepted a British pledge to provide an immediate alliance with France if Germany attacked again, and Wilson agreed to put a similar proposal to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. Clemenceau had told the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

, in December 1918, that his goal was to maintain an alliance with both countries. Clemenceau accepted the offer, in return for an occupation of the Rhineland for fifteen years and that Germany would also demilitarise the Rhineland.

French negotiators required reparations, to make Germany pay for the destruction induced throughout the war and to decrease German strength. The French also wanted the iron ore and coal of the Saar Valley, by annexation to France.

The French were willing to accept a smaller amount of World War I reparations than the Americans would concede and Clemenceau was willing to discuss German capacity to pay with the German delegation, before the final settlement was drafted. In April and May 1919, the French and Germans held separate talks, on mutually acceptable arrangements on issues like reparation, reconstruction and industrial collaboration. France, along with the British Dominions and Belgium, opposed League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

s and favored annexation of former German colonies.

The French, who had suffered significantly in the areas occupied by Germany during the war, were in favour of trying German war criminals, including the Kaiser. In the face of American objections that there was no applicable existing law under which the Kaiser could be tried, Clemenceau took the view that the "law of responsibility" overruled all other laws and that putting the Kaiser on trial offered the opportunity to establish this as an international precedent.

British aims

Britain had suffered heavy financial costs but suffered little physical devastation during the war. British public opinion wanted to make Germany pay for the War.

Public opinion favoured a "just peace", which would force Germany to pay reparations and be unable to repeat the aggression of 1914, although those of a "liberal and advanced opinion" shared Wilson's ideal of a peace of reconciliation.

In private Lloyd George opposed revenge and attempted to compromise between Clemenceau's demands and the Fourteen Points, because Europe would eventually have to reconcile with Germany.

Lloyd George wanted terms of reparation that would not cripple the German economy, so that Germany would remain a viable economic power and trading partner. By arguing that British war pensions and widows' allowances should be included in the German reparation sum, Lloyd George ensured that a large amount would go to the British Empire.

Lloyd George also intended to maintain a European balance of power to thwart a French attempt to establish itself as the dominant European power. A revived Germany would be a counterweight to France and a deterrent to Bolshevik Russia. Lloyd George also wanted to neutralize the German navy to keep the

Britain had suffered heavy financial costs but suffered little physical devastation during the war. British public opinion wanted to make Germany pay for the War.

Public opinion favoured a "just peace", which would force Germany to pay reparations and be unable to repeat the aggression of 1914, although those of a "liberal and advanced opinion" shared Wilson's ideal of a peace of reconciliation.

In private Lloyd George opposed revenge and attempted to compromise between Clemenceau's demands and the Fourteen Points, because Europe would eventually have to reconcile with Germany.

Lloyd George wanted terms of reparation that would not cripple the German economy, so that Germany would remain a viable economic power and trading partner. By arguing that British war pensions and widows' allowances should be included in the German reparation sum, Lloyd George ensured that a large amount would go to the British Empire.

Lloyd George also intended to maintain a European balance of power to thwart a French attempt to establish itself as the dominant European power. A revived Germany would be a counterweight to France and a deterrent to Bolshevik Russia. Lloyd George also wanted to neutralize the German navy to keep the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

as the greatest naval power in the world; dismantle the German colonial empire with several of its territorial possessions ceded to Britain and others being established as League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

s, a position opposed by the Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s.

Together with the French, the British favoured putting German war criminals on trial, and included the Kaiser in this. Already in 1916 Herbert Asquith had declared the intention "to bring to justice the criminals, whoever they be and whatever their station", and a resolution of the war cabinet in 1918 reaffirmed this intent. Lloyd George declared that the British people would not accept a treaty that did not include terms on this, though he wished to limit the charges solely to violation of the 1839 treaty guaranteeing Belgian neutrality. The British were also well aware that the Kaiser having sought refuge in the Netherlands meant that any trial was unlikely to take place and therefore any Article demanding it was likely to be a dead letter.

American aims

Before the American entry into the war, Wilson had talked of a "peace without victory". This position fluctuated following the US entry into the war. Wilson spoke of the German aggressors, with whom there could be no compromised peace. On 8 January 1918, however, Wilson delivered a speech (known as theFourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

) that declared the American peace objectives: the rebuilding of the European economy, self-determination of European and Middle Eastern ethnic groups, the promotion of free trade, the creation of appropriate mandates for former colonies, and above all, the creation of a powerful League of Nations that would ensure the peace. The aim of the latter was to provide a forum to revise the peace treaties as needed, and deal with problems that arose as a result of the peace and the rise of new states.

Wilson brought along top intellectuals as advisors to the American peace delegation, and the overall American position echoed the Fourteen Points. Wilson firmly opposed harsh treatment on Germany. While the British and French wanted to largely annex the German colonial empire, Wilson saw that as a violation of the fundamental principles of justice and human rights of the native populations, and favored them having the right of self-determination via the creation of mandates. The promoted idea called for the major powers to act as disinterested trustees over a region, aiding the native populations until they could govern themselves.

In spite of this position and in order to ensure that Japan did not refuse to join the League of Nations, Wilson favored turning over the former German colony of Shandong

Shandong is a coastal Provinces of China, province in East China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River. It has served as a pivotal cultural ...

, in Eastern China, to the Japanese Empire rather than return the area to the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

's control.

Further confounding the Americans, was US internal partisan politics. In November 1918, the Republican Party won the Senate election by a slim margin. Wilson, a Democrat, refused to include prominent Republicans in the American delegation making his efforts seem partisan, and contributed to a risk of political defeat at home.

On the subject of war crimes, the Americans differed to the British and French in that Wilson's proposal was that any trial of the Kaiser should be solely a political and moral affair, and not one of criminal responsibility, meaning that the death penalty would be precluded. This was based on the American view, particularly those of Robert Lansing, that there was no applicable law under which the Kaiser could be tried. Additionally, the Americans favoured trying other German war criminals before military tribunals rather than an international court, with prosecutions being limited to "violation of the laws and customs of war", and opposed any trials based on violations against what was called " laws of humanity".

Italian aims

Vittorio Emanuele Orlando and his foreign minister Sidney Sonnino, anAnglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

of British origins, worked primarily to secure the partition of the Habsburg Empire and their attitude towards Germany was not as hostile. Generally speaking, Sonnino was in line with the British position while Orlando favored a compromise between Clemenceau and Wilson. Within the negotiations for the Treaty of Versailles, Orlando obtained certain results such as the permanent membership of Italy in the security council of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

and a promised transfer of British Jubaland

Jubaland (; ; ), or the Juba Valley (), is a States and regions of Somalia, Federal Member State in southern Somalia. Its eastern border lies no more than east of the Jubba River, stretching from Dolow to the Indian Ocean, while its western si ...

and French Aozou strip to the Italian colonies of Somalia and Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

respectively. Italian nationalists, however, saw the War as a " mutilated victory" for what they considered to be little territorial gains achieved in the other treaties directly impacting Italy's borders. Orlando was ultimately forced to abandon the conference and resign. Orlando refused to see World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

as a mutilated victory, replying at nationalists calling for a greater expansion that "Italy today is a great state....on par with the great historic and contemporary states. This is, for me, our main and principal expansion." Francesco Saverio Nitti took Orlando's place in signing the treaty of Versailles.da Atti Parlamentari, Camera dei Deputati, Discussioni

The Italian leadership were divided on whether to try the Kaiser. Sonnino considered that putting the Kaiser on trial could result in him becoming a "patriotic martyr". Orlando, in contrast, stated that "the ex-Kaiser ought to pay like other criminals", but was less sure about whether the Kaiser should be ''tried'' as a criminal or merely have a political verdict cast against him. Orlando also considered that " e question of the constitution of the Court presents almost insurmountable difficulties".

Treaty content and signing

In June 1919, the Allies declared that war would resume if the German government did not sign the treaty they had agreed to among themselves. Thegovernment

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

headed by Philipp Scheidemann was unable to agree on a common position, and Scheidemann himself resigned rather than agree to sign the treaty. Gustav Bauer, the head of the new government, sent a telegram stating his intention to sign the treaty if certain articles were withdrawn, including Articles 227 to 231 (i.e., the Articles related to the extradition of the Kaiser for trial, the extradition of German war criminals for trial before Allied tribunals, the handing over of documents relevant for war crimes trials, and accepting liability for war reparations). In response, the Allies issued an ultimatum stating that Germany would have to accept the treaty or face an invasion of Allied forces across the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

within On 23 June, Bauer capitulated and sent a second telegram with a confirmation that a German delegation would arrive shortly to sign the treaty.

On 28 June 1919, the fifth anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was one of the key events that led to World War I. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg ...

(the immediate impetus for the war), the peace treaty was signed. The treaty had clauses ranging from war crimes, the prohibition on the merging of the Republic of German Austria with Germany without the consent of the League of Nations, freedom of navigation on major European rivers, to the returning of a Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

to the king of Hedjaz. Articles 227–230 Article 80 Part XII Article 246

Territorial changes

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, Germany was required to recognize Belgian sovereignty over Moresnet and cede control of the Eupen-Malmedy area. Within six months of the transfer, Belgium was required to conduct a plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

on whether the citizens of the region wanted to remain under Belgian sovereignty or return to German control, communicate the results to the League of Nations and abide by the League's decision. Articles 33 and 34. The Belgian transitional administration, under High Commissioner General Herman Baltia, was responsible for the organisation and control of this process, held between January and June 1920. The plebiscite itself was held without a secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

, and organized as a consultation in which all citizens who opposed the annexation had to formally register their protest. Ultimately, only 271 of 33,726 voters signed the protest list, of which 202 were German state servants. After the Belgian government reported this result, the League of Nations confirmed the change of status on 20 September 1920, with the line of the German-Belgian border finally fixed by a League of Nations commission in 1922. To compensate for the destruction of French coal mines, Germany was to cede the output of the Saar coalmines to France and control of the Saar to the League of Nations for 15 years; a plebiscite would then be held to decide sovereignty. Articles 45 and 49

The treaty restored the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine to France by rescinding the treaties of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

and Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

of 1871 as they pertained to this issue. Section V preamble and Article 51

France was able to make the claim that the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine were indeed part of France and not part of Germany by disclosing a letter sent from the Prussian King to the Empress Eugénie that Eugénie provided, in which William I wrote that the territories of Alsace-Lorraine were requested by Germany for the sole purpose of national defense and not to expand the German territory. The sovereignty of Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; ; ; ; ; occasionally in English ''Sleswick-Holsatia'') is the Northern Germany, northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical Duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of S ...

was to be resolved by a plebiscite to be held at a future time (see Schleswig Plebiscites).

In Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

Germany was to recognize the independence of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

and cede parts of the province of Upper Silesia to them. Articles 81 and 83

Germany had to recognize the independence of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, which had regained its independence following a national revolution against the occupying Central Powers, and renounce "all rights and title" over Polish territory. Portions of Upper Silesia were to be ceded to Poland, with the future of the rest of the province to be decided by plebiscite. The border would be fixed with regard to the vote and to the geographical and economic conditions of each locality. Article 88 and annex

The Province of Posen (now Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

), which had come under Polish control during the Greater Poland Uprising, was also to be ceded to Poland.

Pomerelia (Eastern Pomerania), on historical and ethnic grounds, was transferred to Poland so that the new state could have access to the sea and became known as the Polish Corridor.

The sovereignty of part of southern East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

was to be decided via plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

while the East Prussian Soldau area, which was astride the rail line between Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

and Danzig, was transferred to Poland outright without plebiscite. Article 94

An area of was transferred to Poland under the agreement.

Memel was to be ceded to the Allied and Associated powers, for disposal according to their wishes. Article 99

Germany was to cede the city of Danzig and its hinterland, including the delta of the Vistula River

The Vistula (; ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest in Europe, at in length. Its drainage basin, extending into three other countries apart from Poland, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra ...

on the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

, for the League of Nations to establish the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (; ) was a city-state under the protection and oversight of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) and nearly 200 other small localities in the surrou ...

. Articles 100–104

Mandates

German Kamerun

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern ...

(Cameroon) were transferred to France, aside from portions given to Britain, British Togoland and British Cameroon. Ruanda and Urundi were allocated to Belgium, whereas German South-West Africa went to South Africa and Britain obtained German East Africa. As compensation for the German invasion of Portuguese Africa, Portugal was granted the Kionga Triangle, a sliver of German East Africa in northern Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

.

Article 156 of the treaty transferred German concessions in Shandong

Shandong is a coastal Provinces of China, province in East China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River. It has served as a pivotal cultural ...

, China, to Japan, not to China. Japan was granted all German possessions in the Pacific north of the equator and those south of the equator went to Australia, except for German Samoa, which was taken by New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. Article 156

Military restrictions

The treaty was comprehensive and complex in the restrictions imposed upon the post-war German armed forces (the ). The provisions were intended to make the incapable of offensive action and to encourage international disarmament. Part V preamble Germany was to demobilize sufficient soldiers by 31 March 1920 to leave an army of no more than in a maximum of seven infantry and three cavalry divisions. The treaty laid down the organisation of the divisions and support units, and theGerman General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

was to be dissolved. Articles 159, 160, 163 and Table 1

Military schools for officer training were limited to three, one school per arm, and conscription was abolished. Private soldiers and non-commissioned officers

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is an enlisted rank, enlisted leader, petty officer, or in some cases warrant officer, who does not hold a Commission (document), commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority b ...

were to be retained for at least twelve years and officers for a minimum of with former officers being forbidden to attend military exercises. To prevent Germany from building up a large cadre of trained men, the number of men allowed to leave early was limited. Articles 173, 174, 175 and 176

The number of civilian staff supporting the army was reduced and the police force was reduced to its pre-war size, with increases limited to population increases; paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

forces were forbidden. Articles 161, 162, and 176

The Rhineland was to be demilitarized, all fortifications in the Rhineland and east of the river were to be demolished and new construction was forbidden. Articles 42, 43, and 180

Military structures and fortifications on the islands of Heligoland and Düne

Düne (; ; ) is one of two islands in the German Bight that form the Archipelago of Heligoland, the other being Heligoland proper.

Geography

The small island of Düne is part of the States of Germany, German State of Schleswig-Holstein. Situated ...

were to be destroyed. Article 115

Germany was prohibited from the arms trade, limits were imposed on the type and quantity of weapons and prohibited from the manufacture or stockpile of chemical weapons, armoured cars, tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

s and military aircraft. Articles 165, 170, 171, 172, 198 and tables No. II and III.

The German navy

The German Navy (, ) is part of the unified (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Marine'' (German Navy) became the official ...

was allowed six pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

s and was limited to a maximum of six light cruisers (not exceeding ), twelve destroyers (not exceeding ) and twelve torpedo boats (not exceeding ) and was forbidden submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s. Articles 181 and 190

The manpower of the navy was not to exceed including manning for the fleet, coast defences, signal stations, administration, other land services, officers and men of all grades and corps. The number of officers and warrant officers was not allowed to exceed

Germany surrendered eight battleships

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

, eight light cruisers, forty-two destroyers, and fifty torpedo boats for decommissioning. Thirty-two auxiliary ships

Auxiliary may refer to:

In language

* Auxiliary language (disambiguation)

* Auxiliary verb

In military and law enforcement

* Auxiliary police

* Auxiliaries, civilians or quasi-military personnel who provide support of some kind to a military ...

were to be disarmed and converted to merchant use. Articles 185 and 187

Article 198 prohibited Germany from having an air force, including naval air forces, and required Germany to hand over all aerial related materials. In conjunction, Germany was forbidden to manufacture or import aircraft or related material for a period of six months following the signing of the treaty. Articles 198, 201, and 202

Reparations

In Article 231 Germany accepted responsibility for the losses and damages caused by the war "as a consequence of the ... aggression of Germany and her allies." Article 231 The treaty required Germany to compensate the Allied powers, and it also established an Allied "Reparation Commission" to determine the exact amount which Germany would pay and the form that such payment would take. The commission was required to "give to the German Government a just opportunity to be heard", and to submit its conclusions by . In the interim, the treaty required Germany to pay an equivalent of 20 billion gold marks ($5 billion) in gold, commodities, ships, securities or other forms. The money would help to pay for Allied occupation costs and buy food and raw materials for Germany. Articles 232–235Guarantees

To ensure compliance, the Rhineland and bridgeheads east of the Rhine were to be occupied by Allied troops for fifteen years. Article 428

If Germany had not committed aggression, a staged withdrawal would take place; after five years, the

To ensure compliance, the Rhineland and bridgeheads east of the Rhine were to be occupied by Allied troops for fifteen years. Article 428

If Germany had not committed aggression, a staged withdrawal would take place; after five years, the Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

bridgehead and the territory north of a line along the Ruhr would be evacuated. After ten years, the bridgehead at Coblenz and the territories to the north would be evacuated and after fifteen years remaining Allied forces would be withdrawn. Article 429

If Germany reneged on the treaty obligations, the bridgeheads would be reoccupied immediately. Article 430

International organizations

Part I of the treaty, in common with all the treaties signed during the Paris Peace Conference, was theCovenant of the League of Nations

The Covenant of the League of Nations was the charter of the League of Nations. It was signed on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and became effective together with the rest of the Treaty on 10 January 1920.

Creation

Early ...

, which provided for the creation of the League, an organization for the arbitration of international disputes. Part I

Part XIII organized the establishment of the International Labour Office, to regulate hours of work, including a maximum working day and week; the regulation of the labour supply; the prevention of unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work du ...

; the provision of a living wage; the protection of the worker against sickness, disease and injury arising out of his employment; the protection of children, young persons and women; provision for old age and injury; protection of the interests of workers when employed abroad; recognition of the principle of freedom of association

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline membe ...

; the organization of vocational and technical education and other measures. Constitution of the International Labour Office Part XIII preamble and Article 388

The treaty also called for the signatories to sign or ratify the International Opium Convention. Article 295

War Crimes

Article 227 of the Versailles treaty required the handing over of Kaiser Wilhelm for trial "for supreme offence against international treaties and the sanctity of treaties" before a bench of five allied judges – one British, one American, one French, one Italian, and one Japanese. If found guilty the judges were to "fix such punishment which it considers should be imposed". The death penalty was therefore not precluded. Article 228 allowed the Allies to demand the extradition of German war criminals, who could be tried before military tribunals for crimes against "the laws and customs of war" under Article 229. To provide an evidentiary basis for such trials, Article 230 required the German government to transfer information and documents relevant to such trials.Reactions

Britain

The delegates of the Commonwealth and British Government had mixed thoughts on the treaty, with some seeing the French policy as being greedy and vindictive. Lloyd George and his private secretary Philip Kerr believed in the treaty, although they also felt that the French would keep Europe in a constant state of turmoil by attempting to enforce the treaty. Delegate Harold Nicolson wrote "are we making a good peace?", while General Jan Smuts (a member of the South African delegation) wrote to Lloyd-George, before the signing, that the treaty was unstable and declared "Are we in our sober senses or suffering from shellshock? What has become of Wilson's 14 points?" He wanted the Germans not be made to sign at the "point of the bayonet".

Smuts issued a statement condemning the treaty and regretting that the promises of "a new international order and a fairer, better world are not written in this treaty". Lord Robert Cecil said that many within the