The early history of radio is the

history of technology

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques by humans. Technology includes methods ranging from simple stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and information technology that has emerged since the 19 ...

that produces and uses

radio instruments that use

radio wave

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths g ...

s. Within the

timeline of radio

The timeline of radio lists within the history of radio, the technology and events that produced instruments that use radio waves and activities that people undertook. Later, the history is dominated by programming and contents, which is closer t ...

, many people contributed theory and inventions in what became

radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

. Radio development began as "

wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is the transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using electrical cable, cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimenta ...

". Later radio history increasingly involves matters of

broadcasting

Broadcasting is the data distribution, distribution of sound, audio audiovisual content to dispersed audiences via a electronic medium (communication), mass communications medium, typically one using the electromagnetic spectrum (radio waves), ...

.

Discovery

In an 1864 presentation, published in 1865,

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

proposed theories of

electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge via electromagnetic fields. The electromagnetic force is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. It is the dominant force in the interacti ...

and mathematical proofs demonstrating that light, radio and x-rays were all types of electromagnetic waves propagating through

free space

A vacuum (: vacuums or vacua) is space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective (neuter ) meaning "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressur ...

.

Between 1886 and 1888

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism.

Biography

Heinric ...

published the results of experiments wherein he was able to transmit electromagnetic waves (radio waves) through the air, proving Maxwell's electromagnetic theory.

[ ''Electric waves; being research on the propagation of electric action with finite velocity through space''](_blank)

by Heinrich Rudolph Hertz (English translation by Daniel Evan Jones), Macmillan and Co., 1893, pp. 1–5

Exploration of optical qualities

After their discovery many scientists and inventors experimented with transmitting and detecting "Hertzian waves" (it would take almost 20 years for the term "radio" to be universally adopted for this type of electromagnetic radiation). Maxwell's theory showing that light and Hertzian electromagnetic waves were the same phenomenon at different wavelengths led "Maxwellian" scientists such as John Perry,

Frederick Thomas Trouton

Frederick Thomas Trouton (; 24 November 1863 – 21 September 1922) was an Irish experimental physicist known for Trouton's rule and his experiments to detect the Earth's rotation through the luminiferous aether.

Life and work

Trouton was ...

and Alexander Trotter to assume they would be analogous to optical light.

Following Hertz' untimely death in 1894, British physicist and writer

Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of Radio, radio communication. He identified electromagnetic radiation indepe ...

presented a widely covered lecture on Hertzian waves at the

Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

on June 1 of the same year. Lodge focused on the optical qualities of the waves and demonstrated how to transmit and detect them (using an improved variation of French physicist

Édouard Branly

Édouard Eugène Désiré Branly (, ; ; 23 October 1844 – 24 March 1940) was a French physicist and inventor known for his early involvement in wireless telegraphy and his invention of the coherer in 1890.

Biography

He was born on 23 October 1 ...

's detector Lodge named the "

coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bra ...

"). Lodge further expanded on Hertz' experiments showing how these new waves exhibited like light

refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

,

diffraction

Diffraction is the deviation of waves from straight-line propagation without any change in their energy due to an obstacle or through an aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a secondary source of the Wave propagation ...

,

polarization

Polarization or polarisation may refer to:

Mathematics

*Polarization of an Abelian variety, in the mathematics of complex manifolds

*Polarization of an algebraic form, a technique for expressing a homogeneous polynomial in a simpler fashion by ...

,

interference

Interference is the act of interfering, invading, or poaching. Interference may also refer to:

Communications

* Interference (communication), anything which alters, modifies, or disrupts a message

* Adjacent-channel interference, caused by extra ...

and

standing wave

In physics, a standing wave, also known as a stationary wave, is a wave that oscillates in time but whose peak amplitude profile does not move in space. The peak amplitude of the wave oscillations at any point in space is constant with respect t ...

s,

confirming that Hertz' waves and light waves were both forms of Maxwell's

electromagnetic wave

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) is a self-propagating wave of the electromagnetic field that carries momentum and radiant energy through space. It encompasses a broad spectrum, classified by frequency or its inverse, wavelength, ...

s. During part of the demonstration the waves were sent from the neighboring

Clarendon Laboratory

The Clarendon Laboratory, located on Parks Road within the Science Area in Oxford, England (not to be confused with the Clarendon Building, also in Oxford), is part of the Department of Physics at Oxford University. It houses the atomic and la ...

building, and received by apparatus in the lecture theater.

[James P. Rybak]

Oliver Lodge: Almost the Father of Radio

, pp. 5–6, from Antique Wireless

After Lodge's demonstrations researchers pushed their experiments further down the electromagnetic spectrum towards visible light to further explore the

quasioptical nature at these wavelengths.

Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of Radio, radio communication. He identified electromagnetic radiation indepe ...

and

Augusto Righi

Augusto Righi (; 27 August 1850 – 8 June 1920) was an Italian physicist who was one of the first scientists to produce microwaves.

Biography

Born in Bologna, Righi was educated in his home town, taught physics at Bologna Technical College bet ...

experimented with 1.5 and 12 GHz microwaves respectively, generated by small metal ball spark resonators.

Russian physicist

Pyotr Lebedev

Pyotr Nikolaevich Lebedev (; 24 February 1866 – 1 March 1912) was a Russian physicist. His name was also transliterated as Peter Lebedew and Peter Lebedev. Lebedev was the creator of the first scientific school in Russia.

Career

Lebedev made hi ...

in 1895 conducted experiments in the 50 GHz (6 millimeter) range.

Bengali Indian physicist

Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (; ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a polymath with interests in biology, physics and writing science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions ...

conducted experiments at wavelengths of 60 GHz (5 millimeter) and invented

waveguide

A waveguide is a structure that guides waves by restricting the transmission of energy to one direction. Common types of waveguides include acoustic waveguides which direct sound, optical waveguides which direct light, and radio-frequency w ...

s,

horn antenna

A horn antenna or microwave horn is an antenna (radio), antenna that consists of a flaring metal waveguide shaped like a horn (acoustic), horn to direct radio waves in a beam. Horns are widely used as antennas at Ultrahigh frequency, UHF and m ...

s, and

semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material with electrical conductivity between that of a conductor and an insulator. Its conductivity can be modified by adding impurities (" doping") to its crystal structure. When two regions with different doping level ...

crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers. It consists of a piece of crystalline mineral that rectifies an alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector ( demod ...

s for use in his experiments. He would later write an essay, "Adrisya Alok" ("Invisible Light") on how in November 1895 he conducted a public demonstration at the Town Hall of

Kolkata

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta ( its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River, west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary ...

,

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

using millimeter-range-wavelength microwaves to trigger detectors that ignited gunpowder and rang a bell at a distance.

[Mukherji, Visvapriya, ''Jagadish Chandra Bose, 2nd ed.'' 1994. Builders of Modern India series, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. .]

Proposed applications

Between 1890 and 1892 physicists such as John Perry,

Frederick Thomas Trouton

Frederick Thomas Trouton (; 24 November 1863 – 21 September 1922) was an Irish experimental physicist known for Trouton's rule and his experiments to detect the Earth's rotation through the luminiferous aether.

Life and work

Trouton was ...

and

William Crookes

Sir William Crookes (; 17 June 1832 – 4 April 1919) was an English chemist and physicist who attended the Royal College of Chemistry, now part of Imperial College London, and worked on spectroscopy. He was a pioneer of vacuum tubes, inventing ...

proposed electromagnetic or Hertzian waves as a navigation aid or means of communication, with Crookes writing on the possibilities of wireless

telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas pi ...

based on Hertzian waves in 1892.

[Hong (2001) pp. 5–10] Among physicists, what were perceived as technical limitations to using these new waves, such as delicate equipment, the need for large amounts of power to transmit over limited ranges, and its similarity to already existent optical light transmitting devices, lead them to a belief that applications were very limited. The Serbian American engineer

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla (;["Tesla"](_blank)

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 10 July 1856 – 7 ...

considered Hertzian waves relatively useless for long range transmission since "light" could not transmit further than

line of sight

The line of sight, also known as visual axis or sightline (also sight line), is an imaginary line between a viewer/ observer/ spectator's eye(s) and a subject of interest, or their relative direction. The subject may be any definable object taken ...

. There was speculation that this fog and stormy weather penetrating "invisible light" could be used in maritime applications such as lighthouses.

The London journal ''The Electrician'' (December 1895) commented on Bose's achievements, saying "we may in time see the whole system of coast lighting throughout the navigable world revolutionized by an Indian Bengali scientist working single handed

yin our Presidency College Laboratory."

In 1895, adapting the techniques presented in Lodge's published lectures, Russian physicist

Alexander Stepanovich Popov

Alexander Stepanovich Popov (sometimes spelled Popoff; ; – ) was a Russian physicist who was one of the first people to invent a radio receiving device. declassified 8 January 2008

Popov's work as a teacher at a Russian naval school led hi ...

built a

lightning detector

One of NOAA's National Severe Storms Laboratory Lightning Mapping Array (LMA) sensors

A lightning detector is a device that detects lightning produced by thunderstorms. There are three primary types of detectors: ''ground-based'' systems using ...

that used a coherer based radio receiver. He presented it to the Russian Physical and Chemical Society on May 7, 1895.

Marconi and radio telegraphy

In 1894, the young Italian inventor

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

began working on the idea of building long-distance wireless transmission systems based on the use of Hertzian waves (radio waves), a line of inquiry that he noted other inventors did not seem to be pursuing.

Marconi read through the literature and used the ideas of others who were experimenting with radio waves but did a great deal to develop devices such as portable transmitters and receiver systems that could work over long distances,

turning what was essentially a laboratory experiment into a useful communication system. By August 1895, Marconi was field testing his system but even with improvements he was only able to transmit signals up to one-half mile, a distance Oliver Lodge had predicted in 1894 as the maximum transmission distance for radio waves. Marconi raised the height of his antenna and hit upon the idea of grounding his transmitter and receiver. With these improvements the system was capable of transmitting signals up to and over hills. This apparatus proved to be the first engineering-complete, commercially successful

radio transmission

Radio is the technology of telecommunication, communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transm ...

system

[Correspondence to the editor of the Saturday Review, ''The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art'']

"The Inventor of Wireless Telegraphy: A Reply"

from Guglielmo Marconi (3 May 1902, pp. 556–58) an

"Wireless Telegraphy: A Rejoinder"

from Silvanus P. Thompson (10 May 1902, pp. 598–99) and Marconi went on to file British patent GB189612039A, ''Improvements in transmitting electrical impulses and signals and in apparatus there-for'', in 1896. This patent was granted in the UK on 2 July 1897.

Nautical and transatlantic transmissions

In 1897, Marconi established a radio station on the

Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

, England and opened his "wireless" factory in the former

silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

-works at Hall Street,

Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Colchester and Southend-on-Sea. It is located north-east of London ...

, England, in 1898, employing around 60 people.

On 12 December 1901, using a kite-supported antenna for reception—signals transmitted by the company's new high-power station at

Poldhu

Poldhu () is a small area in south Cornwall, England, UK, situated on the Lizard Peninsula; it comprises Poldhu Point and Poldhu Cove. Poldhu means "black pool" in Cornish. Poldhu lies on the coast of Mount's Bay and is in the northern part ...

, Cornwall, Marconi transmitted a message across the Atlantic Ocean to

Signal Hill in

St. John's,

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

.

[Bondyopadhyay, Prebir K. (1995)]

Guglielmo Marconi – The father of long distance radio communication – An engineer's tribute"

''25th European Microwave Conference: Volume 2'', pp. 879–85

Marconi began to build high-powered stations on both sides of the Atlantic to communicate with ships at sea. In 1904, he established a commercial service to transmit nightly news summaries to subscribing ships, which could incorporate them into their on-board newspapers. A regular transatlantic radio-telegraph service was finally begun on 17 October 1907 between

Clifden

Clifden () is a coastal town in County Galway, Ireland, in the region of Connemara, located on the Owenglin River where it flows into Clifden Bay. As the largest town in the region, it is often referred to as "the Capital of Connemara". Frequen ...

, Ireland, and

Glace Bay

Glace Bay (Scottish Gaelic: ''Glasbaidh'') is a community in the eastern part of the Cape Breton Regional Municipality in Nova Scotia, Canada. It forms part of the general area referred to as Industrial Cape Breton.

Formerly an incorporated ...

, but even after this the company struggled for many years to provide reliable communication to others.

Marconi's apparatus is also credited with saving the 700 people who survived the tragic ''

Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British ocean liner that sank in the early hours of 15 April 1912 as a result of striking an iceberg on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States. Of the estimated 2,224 passengers a ...

'' disaster.

["A Short History of Radio"](_blank)

Winter 2003–2004 (FCC.gov)

Audio transmission

In the late 1890s, Canadian-American inventor

Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-American electrical engineer and inventor who received hundreds of List of Reginald Fessenden patents, patents in fields related to radio and sonar between 1891 and 1936 ...

came to the conclusion that he could develop a far more efficient system than the spark-gap transmitter and coherer receiver combination. To this end he worked on developing a high-speed alternator (referred to as "an alternating-current dynamo") that generated "pure sine waves" and produced "a continuous train of radiant waves of substantially uniform strength", or, in modern terminology, a

continuous-wave

A continuous wave or continuous waveform (CW) is an electromagnetic wave of constant amplitude and frequency, typically a sine wave, that for mathematical analysis is considered to be of infinite duration. It may refer to e.g. a laser or particle ...

(CW) transmitter. While working for the

United States Weather Bureau

The National Weather Service (NWS) is an Government agency, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that is tasked with providing weather forecasts, warnings of hazardous weather, and other weathe ...

on

Cobb Island, Maryland, Fessenden researched using this setup for audio transmissions via radio. By fall of 1900, he successfully transmitted speech over a distance of about 1.6 kilometers (one mile),

["Experiments and Results in Wireless Telephony" by John Grant, ''The American Telephone Journal'']

Part I

January 26, 1907, pp. 49–51

Part II

February 2, 1907, pp. 68–70, 79–80. which appears to have been the first successful audio transmission using radio signals. Although successful, the sound transmitted was far too distorted to be commercially practical. According to some sources, notably Fessenden's wife Helen's biography, on

Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve is the evening or entire day before Christmas, the festival commemorating nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus. Christmas Day is observance of Christmas by country, observed around the world, and Christma ...

1906,

Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-American electrical engineer and inventor who received hundreds of List of Reginald Fessenden patents, patents in fields related to radio and sonar between 1891 and 1936 ...

used an

Alexanderson alternator

An Alexanderson alternator is a rotating machine, developed by Ernst Alexanderson beginning in 1904, for the generation of high-frequency alternating current for use as a radio transmitter. It was one of the first devices capable of generating th ...

and rotary

spark-gap transmitter

A spark-gap transmitter is an obsolete type of transmitter, radio transmitter which generates radio waves by means of an electric spark."Radio Transmitters, Early" in Spark-gap transmitters were the first type of radio transmitter, and were the m ...

to make the first radio audio broadcast, from

Brant Rock, Massachusetts. Ships at sea heard a broadcast that included Fessenden playing ''

O Holy Night

"O Holy Night" (original title: ) is a sacred song about the night of the birth of Jesus Christ, described in the first verse as "the dear Saviour", and frequently performed as a Christmas carol. Based on the French-language poem ''Minuit, ch ...

'' on the

violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

and reading a passage from the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

.

Around the same time American inventor

Lee de Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

experimented with an

arc transmitter, which unlike the discontinuous pulses produced by spark transmitters, created steady "continuous wave" signal that could be used for

amplitude modulated

Amplitude modulation (AM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, most commonly for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In amplitude modulation, the instantaneous amplitude of the wave is varied in proportion t ...

(AM) audio transmissions. In February 1907 he transmitted electronic

telharmonium

The Telharmonium (also known as the Dynamophone) was an early electrical organ, developed by Thaddeus Cahill c. 1896 and patented in 1897.

, filed 1896-02-04.

The electrical signal from the Telharmonium was transmitted over wires; it was hea ...

music from his laboratory station in New York City. This was followed by tests that included, in the fall,

Eugenia Farrar

Eugenia Farrar (1875 – May 17, 1966), whose full name was Ada Eugenia Hildegard von Boos Farrar, was a mezzo-soprano singer and philanthropist. She was born in Sweden and lived most of her life in New York City. In the fall of 1907 she gave wh ...

singing "I Love You Truly". In July 1907 he made ship-to-shore transmissions by radiotelephone—race reports for the Annual Inter-Lakes Yachting Association (I-LYA) Regatta held on

Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( ) is the fourth-largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and also has the shortest avera ...

—which were sent from the steam yacht ''Thelma'' to his assistant, Frank E. Butler, located in the Fox's Dock Pavilion on

South Bass Island

South Bass Island is a small island in western Lake Erie, and a part of Ottawa County, Ohio, United States. It is the southernmost of the three Bass Islands and located 3 miles (4.6 km) from the south shore of Lake Erie. It is the third ...

.

Broadcasting

The Dutch company ''Nederlandsche Radio-Industrie'' and its owner-engineer,

Hanso Idzerda

Hanso Schotanus á Steringa Idzerda (26 September 1885 – 2 November 1944) was a Dutch scientist, entrepreneur and pioneer in radio technology.

Early life and education

Idzerda was born in Weidum, Friesland as the son of Henrikus Idzerda, a c ...

, made its first regular entertainment radio broadcast over station

PCGG

PCGG (also known as the Dutch Concerts station) was a radio station located at The Hague in the Netherlands, which began broadcasting a regular schedule of entertainment programmes on 6 November 1919. The station was established by engineer Hanso ...

from its workshop in

The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

on 6 November 1919. The company manufactured both transmitters and receivers. Its popular program was broadcast four nights per week using narrow-band FM transmissions on 670 metres (448 kHz), until 1924 when the company ran into financial trouble.

Regular entertainment broadcasts began in

Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, pioneered by

Enrique Telémaco Susini

Enrique Telémaco Susini (January 31, 1891 – July 4, 1972) was an Argentine entrepreneur and media pioneer.

In 1920, Susini led the effort for the first radio broadcast in Argentina, and subsequently established one of the earliest regular radi ...

and his associates. At 9 pm on August 27, 1920, Sociedad Radio Argentina aired a live performance of Richard Wagner's opera ''Parsifal'' from the Coliseo Theater in downtown

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

. Only about twenty homes in the city had receivers to tune in this program.

On 31 August 1920 the ''

Detroit News

''The Detroit News'' is one of the two major newspapers in the U.S. city of Detroit, Michigan. The paper began in 1873, when it rented space in the rival ''Detroit Free Press'' building. ''The News'' absorbed the ''Detroit Tribune'' on February ...

'' began publicized daily news and entertainment "Detroit News Radiophone" broadcasts, originally as licensed amateur station 8MK, then later as WBL and

WWJ in

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

.

Union College in Schenectady,

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

began broadcasting on October 14, 1920, over

2ADD, an amateur station licensed to Wendell King, an

African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

student at the school.

Broadcasts included a series of Thursday night concerts initially heard within a radius and later for a radius.

In 1922 regular audio broadcasts for entertainment began in the UK from the

Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based wireless telegraph system. This ...

Research Centre

2MT

2MT was the first British radio station to make regular entertainment broadcasts, and the "world's first regular wireless broadcast" for entertainment. Transmissions began on 14 February 1922 from an ex-Army hut next to the Marconi laboratories ...

at

Writtle

Writtle is a village and civil parish west of Chelmsford, Essex, England. It has a traditional village green complete with duck pond and a Norman church, and was once described as "one of the loveliest villages in England, with a ravishing va ...

near

Chelmsford, England

Chelmsford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Colchester and Southend-on-Sea. It ...

.

Wavelength and frequency

In early radio, and to a limited extent much later, the transmission signal of the radio station was specified in meters, referring to the

wavelength

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same ''phase (waves ...

, the length of the radio wave. This is the origin of the terms

long wave

In radio, longwave (also spelled long wave or long-wave and commonly abbreviated LW) is the part of the radio spectrum with wavelengths longer than what was originally called the medium-wave (MW) broadcasting band. The term is historic, datin ...

,

medium wave

Medium wave (MW) is a part of the medium frequency (MF) radio band used mainly for AM radio broadcasting. The spectrum provides about 120 channels with more limited sound quality than FM stations on the FM broadcast band. During the daytim ...

, and

short wave

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using radio frequencies in the shortwave bands (SW). There is no official definition of the band range, but it always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (app ...

radio. Portions of the radio spectrum reserved for specific purposes were often referred to by wavelength: the

40-meter band

The 40-meter or 7-MHz band is an amateur radio frequency band, spanning 7.000-7.300 MHz in ITU Region 2, and 7.000-7.200 MHz in Regions 1 & 3. It is allocated to radio amateurs worldwide on a primary basis; however, only 7.000-7.200 MH ...

, used for

amateur radio

Amateur radio, also known as ham radio, is the use of the radio frequency radio spectrum, spectrum for purposes of non-commercial exchange of messages, wireless experimentation, self-training, private recreation, radiosport, contesting, and emer ...

, for example. The relation between wavelength and frequency is reciprocal: the higher the frequency, the shorter the wave, and vice versa.

As equipment progressed, precise frequency control became possible; early stations often did not have a precise frequency, as it was affected by the temperature of the equipment, among other factors. Identifying a radio signal by its frequency rather than its length proved much more practical and useful, and starting in the 1920s this became the usual method of identifying a signal, especially in the United States. Frequencies specified in number of cycles per second (kilocycles, megacycles) were replaced by the more specific designation of

hertz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), often described as being equivalent to one event (or Cycle per second, cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose formal expression in ter ...

(cycles per second) about 1965.

Radio companies

British Marconi

Using various

patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

s, the

British Marconi company was established in 1897 by Guglielmo Marconi and began communication between

coast radio station

A coast (or coastal) radio station (short: coast station) is an onshore maritime radio station which monitors radio distress frequencies and relays ship-to-ship and ship-to-land communications.

A coast station (also: '' coast radio station '' ...

s and ships at sea. A year after, in 1898, they successfully introduced their first radio station in Chelmsford. This company, along with its subsidiaries

Canadian Marconi

The Marconi Company was a British telecommunications and engineering company founded by Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi in 1897 which was a pioneer of wireless long distance communication and mass media broadcasting, eventually becoming on ...

and

American Marconi, had a stranglehold on ship-to-shore communication. It operated much the way

American Telephone and Telegraph

AT&T Corporation, an abbreviation for its former name, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, was an American telecommunications company that provided voice, video, data, and Internet telecommunications and professional services to busi ...

operated until 1983, owning all of its equipment and refusing to communicate with non-Marconi equipped ships. Many inventions improved the quality of radio, and amateurs experimented with uses of radio, thus planting the first seeds of broadcasting.

Telefunken

The company

Telefunken

Telefunken was a German radio and television producer, founded in Berlin in 1903 as a joint venture between Siemens & Halske and the ''AEG (German company), Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft'' (AEG) ("General electricity company").

Prior to ...

was founded on May 27, 1903, as "Telefunken society for wireless telefon" of

Siemens & Halske

Siemens & Halske AG (or Siemens-Halske) was a German electrical engineering company that later became part of Siemens.

It was founded on 12 October 1847 as ''Telegraphen-Bauanstalt von Siemens & Halske'' by Werner von Siemens and Johann Geor ...

(S & H) and the

Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (''General Electricity Company'') as joint undertakings for radio engineering in Berlin. It continued as a joint venture of

AEG The initials AEG are used for or may refer to:

Common meanings

* AEG (German company)

; AEG) was a German producer of electrical equipment. It was established in 1883 by Emil Rathenau as the ''Deutsche Edison-Gesellschaft für angewandte El ...

and

Siemens AG

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational technology conglomerate. It is focused on industrial automation, building automation, rail transport and health technology. Siemens is the largest engineering company in Europe, and holds the posit ...

, until Siemens left in 1941. In 1911,

Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty ...

sent Telefunken engineers to

West Sayville

West Sayville is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in Suffolk County, New York, United States. It had a population of 5,011 at the 2010 census.

Geography

West Sayville is located on the South Shore of Long Island in the Town of Islip. ...

,

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

to erect three 600-foot (180-m) radio towers there. Nikola Tesla assisted in the construction. A similar station was erected in

Nauen

Nauen is a small town in the Havelland (district), Havelland district, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is chiefly known for Nauen Transmitter Station, the world's oldest preserved radio transmitting installation.

Geography

Nauen is situated within t ...

, creating the only wireless communication between North America and Europe.

Technological development

Amplitude-modulated (AM)

The invention of amplitude-modulated (AM) radio, which allows more closely spaced stations to simultaneously send signals (as opposed to spark-gap radio, where each transmission occupies a wide bandwidth) is attributed to

Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-American electrical engineer and inventor who received hundreds of List of Reginald Fessenden patents, patents in fields related to radio and sonar between 1891 and 1936 ...

,

Valdemar Poulsen

Valdemar Poulsen (23 November 1869 – 23 July 1942) was a Danish engineer who developed a magnetic wire recorder called the telegraphone in 1898. He also made significant contributions to early radio technology, including the first continuous w ...

and

Lee de Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

.

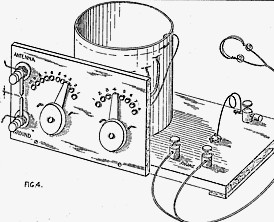

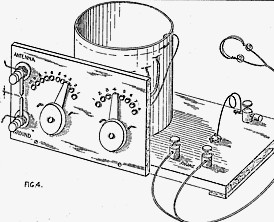

Crystal set receivers

The most common type of receiver before vacuum tubes was the

crystal set, although some early radios used some type of amplification through electric current or battery. Inventions of the

triode amplifier

A triode is an electronic amplifying vacuum tube (or ''thermionic valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated filament or cathode, a grid, and a plate (anode).

Developed from Lee ...

,

motor-generator, and

detector

A sensor is often defined as a device that receives and responds to a signal or stimulus. The stimulus is the quantity, property, or condition that is sensed and converted into electrical signal.

In the broadest definition, a sensor is a devi ...

enabled audio radio. The use of

amplitude modulation

Amplitude modulation (AM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, most commonly for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In amplitude modulation, the instantaneous amplitude of the wave is varied in proportion t ...

(

AM), by which soundwaves can be transmitted over a continuous-wave radio signal of narrow bandwidth (as opposed to spark-gap radio, which sent rapid strings of damped-wave pulses that consumed much bandwidth and were only suitable for Morse-code telegraphy) was pioneered by Fessenden, Poulsen and Lee de Forest.

The art and science of crystal sets is still pursued as a hobby in the form of simple un-amplified radios that 'runs on nothing, forever'. They are used as a teaching tool by groups such as the

Boy Scouts of America

Scouting America is the largest scouting organization and one of the largest List of youth organizations, youth organizations in the United States, with over 1 million youth, including nearly 200,000 female participants. Founded as the Boy Sco ...

to introduce youngsters to electronics and radio. As the only energy available is that gathered by the antenna system, loudness is necessarily limited.

Vacuum tubes

During the mid-1920s, amplifying

vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

s revolutionized

radio receiver

In radio communications, a radio receiver, also known as a receiver, a wireless, or simply a radio, is an electronic device that receives radio waves and converts the information carried by them to a usable form. It is used with an antenna. ...

s and

transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter (often abbreviated as XMTR or TX in technical documents) is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna (radio), antenna with the purpose of sig ...

s.

John Ambrose Fleming

Sir John Ambrose Fleming (29 November 1849 – 18 April 1945) was an English electrical engineer who invented the vacuum tube, designed the radio transmitter with which the first transatlantic radio transmission was made, and also established ...

developed a vacuum tube

diode

A diode is a two-Terminal (electronics), terminal electronic component that conducts electric current primarily in One-way traffic, one direction (asymmetric electrical conductance, conductance). It has low (ideally zero) Electrical resistance ...

.

Lee de Forest #REDIRECT Lee de Forest

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from other capitalisation ...

placed a screen, added a

"grid" electrode, creating the

triode

A triode is an electronic amplifier, amplifying vacuum tube (or ''thermionic valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated Electrical filament, filament or cathode, a control grid, grid ...

.

Early radios ran the entire power of the transmitter through a

carbon microphone

The carbon microphone, also known as carbon button microphone, button microphone, or carbon transmitter, is a type of microphone, a transducer that converts sound to an electrical audio signal. It consists of two metal plates separated by granu ...

. In the 1920s, the

Westinghouse company bought Lee de Forest's and

Edwin Armstrong

Edwin Howard Armstrong (December 18, 1890 – February 1, 1954) was an American electrical engineer and inventor who developed FM (frequency modulation) radio and the superheterodyne receiver system.

He held 42 patents and received numerous aw ...

's patent. During the mid-1920s, Amplifying

vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

s revolutionized

radio receiver

In radio communications, a radio receiver, also known as a receiver, a wireless, or simply a radio, is an electronic device that receives radio waves and converts the information carried by them to a usable form. It is used with an antenna. ...

s and transmitters. Westinghouse engineers developed a more modern vacuum tube.

The first radios still required batteries, but in 1926 the "

battery eliminator

An AC adapter or AC/DC adapter (also called a wall charger, power adapter, power brick, or wall wart) is a type of external power supply, often enclosed in a case similar to an AC power plugs and sockets, AC plug. AC adapters deliver electri ...

" was introduced to the market. This tube technology allowed radios to be powered through the grid instead. They still required batteries to heat up the vacuum-tube filaments, but after the invention of

indirectly heated vacuum tubes, the first completely battery free radios became available in 1927.

In 1929 a new screen grid tube called UY-224 was introduced, an amplifier designed to operate directly on alternating current.

A problem with the early radios was fading stations and fluctuating volume. The invention of the

superheterodyne receiver

A superheterodyne receiver, often shortened to superhet, is a type of radio receiver that uses frequency mixing to convert a received signal to a fixed intermediate frequency (IF) which can be more conveniently processed than the original car ...

solved this problem, and the first radios with a heterodyne radio receiver went for sale in 1924. But it was costly, and the technology was shelved while waiting for the technology to mature, and in 1929 the Radiola 66 and Radiola 67 went for sale.

Loudspeakers

In the early days one had to use headphones to listen to radio. Later loudspeakers in the form of a horn of the type used by phonographs, equipped with a telephone receiver, became available. But the sound quality was poor. In 1926 the first radios with electrodynamic loudspeakers went for sale, which improved the quality significantly. At first the loudspeakers were separated from the radio, but soon radios would come with a built-in loudspeaker.

Other inventions related to sound included the automatic volume control (AVC), first commercially available in 1928. In 1930 a tone control knob was added to the radios. This allowed listeners to improve imperfect broadcasting.

The

magnetic cartridge

A magnetic cartridge, more commonly called a phonograph cartridge or phono cartridge or (colloquially) a pickup, is an electromechanical transducer that is used to play phonograph records on a Phonograph, turntable.

The cartridge contains a re ...

, which was introduced in the mid 20's, greatly improved the broadcasting of music. When playing music from a phonograph before the magnetic cartridge, a microphone had to be placed close to a horn loudspeaker. The invention allowed the electric signals to be amplified and then fed directly to the

broadcast transmitter

A broadcast transmitter is an electronic device that radiates radio waves modulated with information content intended to be received by the general public. Examples are a transmitter, radio broadcasting transmitter which transmits Sound, audio (s ...

.

Transistor technology

Following development of

transistor

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch electrical signals and electric power, power. It is one of the basic building blocks of modern electronics. It is composed of semicondu ...

technology,

bipolar junction transistor

A bipolar junction transistor (BJT) is a type of transistor that uses both electrons and electron holes as charge carriers. In contrast, a unipolar transistor, such as a field-effect transistor (FET), uses only one kind of charge carrier. A ...

s led to the development of the

transistor radio

A transistor radio is a small portable radio receiver that uses transistor-based circuitry. Previous portable radios used vacuum tubes, which were bulky, fragile, had a limited lifetime, consumed excessive power and required large heavy batteri ...

. In 1954, the Regency company introduced a pocket transistor radio, the

TR-1, powered by a "standard 22.5 V Battery." In 1955, the newly formed

Sony

is a Japanese multinational conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at Sony City in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. The Sony Group encompasses various businesses, including Sony Corporation (electronics), Sony Semiconductor Solutions (i ...

company introduced its first transistorized radio, the

TR-55.

It was small enough to fit in a

vest

A waistcoat ( UK and Commonwealth, or ; colloquially called a weskit) or vest ( US and Canada) is a sleeveless upper-body garment. It is usually worn over a dress shirt and necktie and below a coat as a part of most men's formal wear. It ...

pocket, powered by a small battery. It was durable, because it had no vacuum tubes to burn out. In 1957, Sony introduced the TR-63, the first mass-produced transistor radio, leading to the mass-market penetration of transistor radios.

Over the next 20 years, transistors replaced tubes almost completely except for high-power

transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter (often abbreviated as XMTR or TX in technical documents) is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna (radio), antenna with the purpose of sig ...

s.

By the mid-1960s, the

Radio Corporation of America

RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded in 1919 as the Radio Corporation of America. It was initially a patent pool, patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Westinghou ...

(RCA) were using

metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor

upright=1.3, Two power MOSFETs in amperes">A in the ''on'' state, dissipating up to about 100 watt">W and controlling a load of over 2000 W. A matchstick is pictured for scale.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field- ...

s (MOSFETs) in their consumer products, including

FM radio

FM broadcasting is a method of radio broadcasting that uses frequency modulation (FM) of the radio broadcast carrier wave. Invented in 1933 by American engineer Edwin Armstrong, wide-band FM is used worldwide to transmit high fidelity, high-f ...

, television and

amplifier

An amplifier, electronic amplifier or (informally) amp is an electronic device that can increase the magnitude of a signal (a time-varying voltage or current). It is a two-port electronic circuit that uses electric power from a power su ...

s.

Metal–oxide–semiconductor

upright=1.3, Two power MOSFETs in amperes">A in the ''on'' state, dissipating up to about 100 watt">W and controlling a load of over 2000 W. A matchstick is pictured for scale.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field- ...

(MOS)

large-scale integration

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a set of electronic circuits, consisting of various electronic components (such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors) and their interconnections. These components a ...

(LSI) provided a practical and economic solution for radio technology, and was used in

mobile radio

Mobile radio or mobiles refer to wireless communications systems and devices which are based on radio frequencies (using commonly UHF or VHF frequencies), and where the path of communications is movable on either end. There are a variety of vi ...

systems by the early 1970s.

Integrated circuit

The first integrated circuit (IC) radio, P1740 by

General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

, became available in 1966.

Car radio

The first car radio was introduced in 1922, but it was so large that it took up too much space in the car. The first commercial car radio that could easily be installed in most cars went for sale in 1930.

Radio telex

Telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas pi ...

did not go away on radio. Instead, the degree of automation increased. On land-lines in the 1930s,

teletypewriter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations.

Init ...

s automated encoding, and were adapted to pulse-code dialing to automate routing, a service called

telex

Telex is a telecommunication

Telecommunication, often used in its plural form or abbreviated as telecom, is the transmission of information over a distance using electronic means, typically through cables, radio waves, or other communica ...

. For thirty years, telex was the cheapest form of long-distance communication, because up to 25 telex channels could occupy the same bandwidth as one voice channel. For business and government, it was an advantage that telex directly produced written documents.

Telex systems were adapted to short-wave radio by sending tones over

single sideband

In radio communications, single-sideband modulation (SSB) or single-sideband suppressed-carrier modulation (SSB-SC) is a type of signal modulation used to transmit information, such as an audio signal, by radio waves. A refinement of amplitud ...

.

CCITT

The International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) is one of the three Sectors (branches) of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). It is responsible for coordinating standards for telecommunicat ...

R.44 (the most advanced pure-telex standard) incorporated character-level error detection and retransmission as well as automated encoding and routing. For many years, telex-on-radio (TOR) was the only reliable way to reach some third-world countries. TOR remains reliable, though less-expensive forms of e-mail are displacing it. Many national telecom companies historically ran nearly pure telex networks for their governments, and they ran many of these links over short wave radio.

Documents including maps and photographs went by

radiofax

Radiofacsimile, radiofax or HF fax is an analogue mode for transmitting grayscale images via high frequency (HF) radio waves. It was the predecessor to slow-scan television (SSTV). It was the primary method of sending photographs from remote sit ...

, or wireless photoradiogram, invented in 1924 by

Richard H. Ranger

Richard Howland Ranger (13 June 1889 – 10 January 1962) was an American electrical engineer, music engineer and inventor. He was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, the son of John Hilliard and Emily Anthen Gillet Ranger, He served in the U.S. Ar ...

of

Radio Corporation of America

RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded in 1919 as the Radio Corporation of America. It was initially a patent pool, patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Westinghou ...

(RCA). This method prospered in the mid-20th century and faded late in the century.

Radio navigation

One of the first developments in the early 20th century was that aircraft used commercial AM radio stations for navigation, AM stations are still marked on U.S. aviation charts.

Radio navigation

Radio navigation or radionavigation is the application of radio waves to geolocalization, determine a position of an object on the Earth, either the vessel or an obstruction. Like radiolocation, it is a type of Radiodetermination-satellite servi ...

played an important role during war time, especially in World War II. Before the discovery of the crystal oscillator, radio navigation had many limits. However, as radio technology expanding, navigation is easier to use, and it provides a better position. Although there are many advantages, the radio navigation systems often comes with complex equipment such as the radio compass receiver, compass indicator, or the radar plan position indicator. All of these require users to obtain certain knowledge.

In the 1960s

VOR systems became widespread. In the 1970s,

LORAN

LORAN (Long Range Navigation) was a hyperbolic navigation, hyperbolic radio navigation system developed in the United States during World War II. It was similar to the UK's Gee (navigation), Gee system but operated at lower frequencies in order ...

became the premier radio navigation system. Soon, the US Navy experimented with

satellite navigation

A satellite navigation or satnav system is a system that uses satellites to provide autonomous geopositioning. A satellite navigation system with global coverage is termed global navigation satellite system (GNSS). , four global systems are ope ...

. In 1987, the

Global Positioning System

The Global Positioning System (GPS) is a satellite-based hyperbolic navigation system owned by the United States Space Force and operated by Mission Delta 31. It is one of the global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) that provide ge ...

(GPS) constellation of

satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scient ...

s was launched; it was followed by other

GNSS

A satellite navigation or satnav system is a system that uses satellites to provide autonomous geopositioning. A satellite navigation system with global coverage is termed global navigation satellite system (GNSS). , four global systems are op ...

systems like

Glonass

GLONASS (, ; ) is a Russian satellite navigation system operating as part of a radionavigation-satellite service. It provides an alternative to Global Positioning System (GPS) and is the second navigational system in operation with global cove ...

,

BeiDou

The BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS; ) is a satellite-based radio navigation system owned and operated by the China National Space Administration. It provides geolocation and time information to a BDS receiver anywhere on or near the ...

and

Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

.

FM

In 1933,

FM radio

FM broadcasting is a method of radio broadcasting that uses frequency modulation (FM) of the radio broadcast carrier wave. Invented in 1933 by American engineer Edwin Armstrong, wide-band FM is used worldwide to transmit high fidelity, high-f ...

was patented by inventor

Edwin H. Armstrong. FM uses

frequency modulation

Frequency modulation (FM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, originally for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In frequency modulation a carrier wave is varied in its instantaneous frequency in proporti ...

of the radio wave to reduce

static and

interference

Interference is the act of interfering, invading, or poaching. Interference may also refer to:

Communications

* Interference (communication), anything which alters, modifies, or disrupts a message

* Adjacent-channel interference, caused by extra ...

from electrical equipment and the atmosphere. In 1937,

W1XOJ

WGTR was a pioneer commercial FM radio station, which was the first of two mountain-top stations established by the Yankee Network. It began regular programming, as experimental station W1XOJ, in 1939. In 1941 it was licensed for commercial ope ...

, the first experimental FM radio station after Armstrong's

W2XMN

W2XMN was an experimental FM radio station located in Alpine, New Jersey. It was constructed beginning in 1936 by Edwin Howard Armstrong in order to promote his invention of wide-band FM broadcasting. W2XMN was the first FM station to begin regu ...

in Alpine, New Jersey, was granted a construction permit by the US

Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, internet, wi-fi, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains j ...

(FCC).

FM in Europe

After World War II,

FM radio

FM broadcasting is a method of radio broadcasting that uses frequency modulation (FM) of the radio broadcast carrier wave. Invented in 1933 by American engineer Edwin Armstrong, wide-band FM is used worldwide to transmit high fidelity, high-f ...

broadcasting was introduced in Germany. At a meeting in

Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

in 1948, a new

wavelength plan

The radio spectrum is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum with frequencies from 3 Hz to 3,000 GHz (3 THz). Electromagnetic waves in this frequency range, called radio waves, are widely used in modern technology, particularl ...

was set up for Europe. Because of the recent war, Germany (which did not exist as a state and so was not invited) was only given a small number of

medium-wave

Medium wave (MW) is a part of the medium frequency (MF) radio band used mainly for AM radio broadcasting. The spectrum provides about 120 channels with more limited sound quality than FM stations on the FM broadcast band. During the daytime, ...

frequencies, which were not very good for broadcasting. For this reason Germany began broadcasting on UKW ("Ultrakurzwelle", i.e. ultra short wave, nowadays called

VHF) which was not covered by the Copenhagen plan. After some

amplitude modulation

Amplitude modulation (AM) is a signal modulation technique used in electronic communication, most commonly for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In amplitude modulation, the instantaneous amplitude of the wave is varied in proportion t ...

experience with VHF, it was realized that FM radio was a much better alternative for VHF radio than AM. Because of this history, FM radio is still referred to as "UKW Radio" in Germany. Other European nations followed a bit later, when the superior sound quality of FM and the ability to run many more local stations because of the more limited range of VHF broadcasts were realized.

Television

In the 1930s, regular

analog television

Analog television is the original television technology that uses analog signals to transmit video and audio. In an analog television broadcast, the brightness, colors and sound are represented by amplitude, instantaneous phase and frequency, ...

broadcasting began in some parts of Europe and North America. By the end of the decade there were roughly 25,000 all-electronic television receivers in existence worldwide, the majority of them in the UK. In the US, Armstrong's FM system was designated by the FCC to transmit and receive television sound.

Color television

* 1953:

NTSC

NTSC (from National Television System Committee) is the first American standard for analog television, published and adopted in 1941. In 1961, it was assigned the designation System M. It is also known as EIA standard 170.

In 1953, a second ...

compatible

color television

Color television (American English) or colour television (British English) is a television transmission technology that also includes color information for the picture, so the video image can be displayed in color on the television set. It improv ...

introduced in the US.

* 1962:

Telstar 1

Telstar 1 is a defunct communications satellite launched by NASA on July 10, 1962. One of the earliest communications satellites, it was the first satellite to achieve live transmission of broadcast television images between the United States ...

, the first

communications satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a Transponder (satellite communications), transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a Rad ...

, relayed the first publicly available live transatlantic

television

Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

signal.

* Mid-1960s:

Metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor

upright=1.3, Two power MOSFETs in amperes">A in the ''on'' state, dissipating up to about 100 watt">W and controlling a load of over 2000 W. A matchstick is pictured for scale.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field- ...

(MOSFET) first used for television, by the

Radio Corporation of America

RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded in 1919 as the Radio Corporation of America. It was initially a patent pool, patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Westinghou ...

(RCA).

The

power MOSFET

A power MOSFET is a specific type of metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) designed to handle significant power levels. Compared to the other power semiconductor devices, such as an insulated-gate bipolar transistor (IG ...

was later widely adopted for

television receiver

A television set or television receiver (more commonly called TV, TV set, television, telly, or tele) is an electronic device for viewing and hearing television broadcasts, or as a computer monitor. It combines a tuner, display, and loudspeake ...

circuits.

By 1963,

color television

Color television (American English) or colour television (British English) is a television transmission technology that also includes color information for the picture, so the video image can be displayed in color on the television set. It improv ...

was being broadcast commercially (though not all broadcasts or programs were in color), and the first (radio)

communication satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a receiver at different locations on Earth. ...

, ''

Telstar

Telstar refers to a series of communications satellites. The first two, Telstar 1 and Telstar 2, were experimental and nearly identical. Telstar 1 launched atop of a Thor-Delta rocket on July 10, 1962, successfully relayed the first televisi ...

'', was launched. In the 1970s,

Mobile phones

In 1947 AT&T commercialized the

Mobile Telephone Service

The Mobile Telephone Service (MTS) was a pre- cellular VHF radio system that linked to the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN). MTS was the radiotelephone equivalent of land dial phone service.

The Mobile Telephone Service was one of the ea ...

. From its start in St. Louis in 1946, AT&T then introduced Mobile Telephone Service to one hundred towns and highway corridors by 1948. Mobile Telephone Service was a rarity with only 5,000 customers placing about 30,000 calls each week. Because only three radio channels were available, only three customers in any given city could make mobile telephone calls at one time.

[Gordon A. Gow, Richard K. Smith ''Mobile and wireless communications: an introduction'', McGraw-Hill International, 2006 p. 23] Mobile Telephone Service was expensive, costing US$15 per month, plus $0.30–0.40 per local call, equivalent to (in 2012 US dollars) about $176 per month and $3.50–4.75 per call.

The

Advanced Mobile Phone System

Advanced Mobile Phone System (AMPS) was an analog mobile phone system standard originally developed by Bell Labs and later modified in a cooperative effort between Bell Labs and Motorola. It was officially introduced in the Americas on October ...

analog mobile phone system, developed by

Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

, was introduced in the Americas in 1978,

[Private Line: Daily Notes Archive (October 2003)](_blank)

by Tom Farley .

by Kathi Ann Brown (extract from ''Bringing Information to People'', 1993) (MilestonesPast.com) gave much more capacity. It was the primary analog mobile phone system in North America (and other locales) through the 1980s and into the 2000s.

The development of

metal–oxide–semiconductor

upright=1.3, Two power MOSFETs in amperes">A in the ''on'' state, dissipating up to about 100 watt">W and controlling a load of over 2000 W. A matchstick is pictured for scale.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field- ...

(MOS)

large-scale integration

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a set of electronic circuits, consisting of various electronic components (such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors) and their interconnections. These components a ...

(LSI) technology,

information theory

Information theory is the mathematical study of the quantification (science), quantification, Data storage, storage, and telecommunications, communication of information. The field was established and formalized by Claude Shannon in the 1940s, ...

and

cellular network

A cellular network or mobile network is a telecommunications network where the link to and from end nodes is wireless network, wireless and the network is distributed over land areas called ''cells'', each served by at least one fixed-locatio ...

ing led to the development of affordable

mobile communications

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobil ...

.

The

Advanced Mobile Phone System

Advanced Mobile Phone System (AMPS) was an analog mobile phone system standard originally developed by Bell Labs and later modified in a cooperative effort between Bell Labs and Motorola. It was officially introduced in the Americas on October ...

analog mobile phone system, developed by

Bell Labs

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

and introduced in the

Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

in 1978,

gave much more capacity. It was the primary analog mobile phone system in

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

(and other locales) through the 1980s and into the 2000s.

Broadcast and copyright

The British government and the state-owned postal services found themselves under massive pressure from the wireless industry (including telegraphy) and early radio adopters to open up to the new medium. In an internal confidential report from February 25, 1924, the ''Imperial Wireless Telegraphy Committee'' stated:

:"We have been asked 'to consider and advise on the policy to be adopted as regards the Imperial Wireless Services so as to protect and facilitate public interest.' It was impressed upon us that the question was urgent. We did not feel called upon to explore the past or to comment on the delays which have occurred in the building of the Empire Wireless Chain. We concentrated our attention on essential matters, examining and considering the facts and circumstances which have a direct bearing on policy and the condition which safeguard public interests."

When radio was introduced in the early 1920s, many predicted it would kill the

phonograph record

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English) or a vinyl record (for later varieties only) is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The g ...

industry. Radio was a free medium for the public to hear music for which they would normally pay. While some companies saw radio as a new avenue for promotion, others feared it would cut into profits from record sales and live performances. Many record companies would not license their records to be played over the radio, and had their major stars sign agreements that they would not perform on radio broadcasts.

Indeed, the music recording industry had a severe drop in profits after the introduction of the radio. For a while, it appeared as though radio was a definite threat to the record industry. Radio ownership grew from two out of five homes in 1931 to four out of five homes in 1938. Meanwhile, record sales fell from $75 million in 1929 to $26 million in 1938 (with a low point of $5 million in 1933), though the economics of the situation were also affected by the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

The copyright owners were concerned that they would see no gain from the popularity of radio and the 'free' music it provided. What they needed to make this new medium work for them already existed in previous copyright law. The copyright holder for a song had control over all public performances 'for profit.' The problem now was proving that the radio industry, which was just figuring out for itself how to make money from advertising and currently offered free music to anyone with a receiver, was making a profit from the songs.

The

test case

In software engineering, a test case is a specification of the inputs, execution conditions, testing procedure, and expected results that define a single test to be executed to achieve a particular software testing objective, such as to exercise ...

was against

Bamberger's

Bamberger's was a department store chain with branches primarily in New Jersey and other locations in Delaware, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania. The chain was headquartered in Newark, New Jersey.

History 19th century

Newark was known for m ...

Department Store in

Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, the county seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County, and a principal city of the New York metropolitan area. ...