United States' Entry Into World War I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Britain used its large navy to prevent cargo vessels entering German ports, mainly by intercepting them in the

Britain used its large navy to prevent cargo vessels entering German ports, mainly by intercepting them in the

Leaders of most religious groups (except the Episcopalians) tended to pacifism, as did leaders of the woman's movement. The Methodists and Quakers among others were vocal opponents of the war. President Wilson, who was a devout Presbyterian, would often frame the war in terms of good and evil in an appeal for religious support of the war.

A concerted effort was made by pacifists including

Leaders of most religious groups (except the Episcopalians) tended to pacifism, as did leaders of the woman's movement. The Methodists and Quakers among others were vocal opponents of the war. President Wilson, who was a devout Presbyterian, would often frame the war in terms of good and evil in an appeal for religious support of the war.

A concerted effort was made by pacifists including

The Preparedness movement had a " realistic" philosophy of world affairs—they believed that economic strength and military muscle were more decisive than idealistic crusades focused on causes like democracy and national self-determination. Emphasizing over and over the weak state of national defenses, they showed that the US's 100,000-man Army even augmented by the 112,000 National Guardsmen, was outnumbered 20 to one by Germany's army, which was drawn from a smaller population. Similarly in 1915, the armed forces of Britain and her Empire,

The Preparedness movement had a " realistic" philosophy of world affairs—they believed that economic strength and military muscle were more decisive than idealistic crusades focused on causes like democracy and national self-determination. Emphasizing over and over the weak state of national defenses, they showed that the US's 100,000-man Army even augmented by the 112,000 National Guardsmen, was outnumbered 20 to one by Germany's army, which was drawn from a smaller population. Similarly in 1915, the armed forces of Britain and her Empire,  Wilson's program for the Army touched off a firestorm. Secretary of War Lindley Garrison adopted many of the proposals of the Preparedness leaders, especially their emphasis on a large federal reserve and abandonment of the National Guard. Garrison's proposals not only outraged the localistic politicians of both parties, they also offended a strongly held belief shared by the liberal wing of the Progressive movement. They felt that warfare always had a hidden economic motivation. Specifically, they warned the chief warmongers were New York bankers (like

Wilson's program for the Army touched off a firestorm. Secretary of War Lindley Garrison adopted many of the proposals of the Preparedness leaders, especially their emphasis on a large federal reserve and abandonment of the National Guard. Garrison's proposals not only outraged the localistic politicians of both parties, they also offended a strongly held belief shared by the liberal wing of the Progressive movement. They felt that warfare always had a hidden economic motivation. Specifically, they warned the chief warmongers were New York bankers (like

By 1916 a new factor was emerging—a sense of national self-interest and US nationalism. The unbelievable casualty figures in Europe were sobering—two vast battles caused over one million casualties each. Clearly this war would be a decisive episode in the history of the world. Every effort to find a peaceful solution was frustrated.

By 1916 a new factor was emerging—a sense of national self-interest and US nationalism. The unbelievable casualty figures in Europe were sobering—two vast battles caused over one million casualties each. Clearly this war would be a decisive episode in the history of the world. Every effort to find a peaceful solution was frustrated.

In early 1917, Kaiser Wilhelm II forced the issue. After discussions in a 9 January 1917 German Crown Council meeting, the decision was made public on January 31, 1917, to target neutral shipping in a designated war-zone. This became the immediate cause of the entry of the United States into the war.

Germany sank ten US merchant ships from February 3, 1917, through April 4, 1917, though news about the schooner ''Marguerite'' did not arrive until after Wilson signed the declaration of war.

Outraged public opinion now overwhelmingly supported Wilson when he asked Congress for a declaration of war on April 2, 1917.

It was voted approved by a Joint Session (not merely the Senate) on April 6, 1917, and Wilson signed it the following afternoon.

In early 1917, Kaiser Wilhelm II forced the issue. After discussions in a 9 January 1917 German Crown Council meeting, the decision was made public on January 31, 1917, to target neutral shipping in a designated war-zone. This became the immediate cause of the entry of the United States into the war.

Germany sank ten US merchant ships from February 3, 1917, through April 4, 1917, though news about the schooner ''Marguerite'' did not arrive until after Wilson signed the declaration of war.

Outraged public opinion now overwhelmingly supported Wilson when he asked Congress for a declaration of war on April 2, 1917.

It was voted approved by a Joint Session (not merely the Senate) on April 6, 1917, and Wilson signed it the following afternoon.

The Germans had anticipated that

The Germans had anticipated that

Historians such as Ernest R. May have approached the process of the US entry into the war as a study in how public opinion changed radically in three years' time. In 1914 most Americans called for neutrality, seeing the war as a dreadful mistake and were determined to stay out. By 1917 the same public felt just as strongly that going to war was both necessary and wise. Military leaders had little to say during this debate, and military considerations were seldom raised. The decisive questions dealt with morality and visions of the future. The prevailing attitude was that the US possessed a superior moral position as the only great nation devoted to the principles of freedom and democracy. By staying aloof from the squabbles of reactionary empires, it could preserve those ideals—sooner or later the rest of the world would come to appreciate and adopt them. In 1917 this very long-run program faced the severe danger that in the short run powerful forces adverse to democracy and freedom would triumph. Strong support for moralism came from religious leaders, women (led by

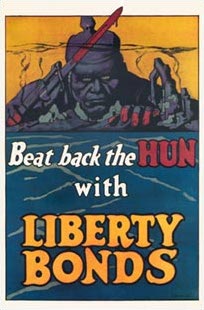

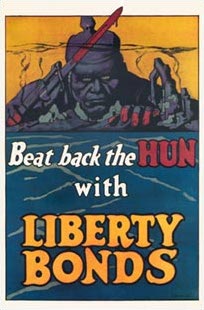

Historians such as Ernest R. May have approached the process of the US entry into the war as a study in how public opinion changed radically in three years' time. In 1914 most Americans called for neutrality, seeing the war as a dreadful mistake and were determined to stay out. By 1917 the same public felt just as strongly that going to war was both necessary and wise. Military leaders had little to say during this debate, and military considerations were seldom raised. The decisive questions dealt with morality and visions of the future. The prevailing attitude was that the US possessed a superior moral position as the only great nation devoted to the principles of freedom and democracy. By staying aloof from the squabbles of reactionary empires, it could preserve those ideals—sooner or later the rest of the world would come to appreciate and adopt them. In 1917 this very long-run program faced the severe danger that in the short run powerful forces adverse to democracy and freedom would triumph. Strong support for moralism came from religious leaders, women (led by  In 1917 Wilson won the support of most of the moralists by proclaiming "a war to make the world safe for democracy." If they truly believed in their ideals, he explained, now was the time to fight. The question then became whether Americans would fight for what they deeply believed in, and the answer turned out to be a resounding "Yes". Some of this attitude was mobilised by the Spirit of 1917, which evoked the Spirit of '76.

Antiwar activists at the time and in the 1930s, alleged that beneath the veneer of moralism and idealism there must have been ulterior motives. Some suggested a conspiracy on the part of New York City bankers holding $3 billion of war loans to the Allies, or steel and chemical firms selling munitions to the Allies. The interpretation was popular among left-wing Progressives (led by Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin) and among the "agrarian" wing of the Democratic party—including the chairman of the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee of the House. He strenuously opposed war, and when it came he rewrote the tax laws to make sure the rich paid the most. (In the 1930s neutrality laws were passed to prevent financial entanglements from dragging the nation into a war.) In 1915, Bryan thought that Wilson's pro-British sentiments had unduly influenced his policies, so he became the first Secretary of State ever to resign in protest.

However, historian Harold C. Syrett demonstrated that business in general supported neutrality. Other historians state that the pro-war element was animated not by profit but by disgust with what Germany actually did, especially in Belgium, and the threat it represented to US ideals. Belgium kept the public's sympathy as the Germans executed civilians, and English nurse

In 1917 Wilson won the support of most of the moralists by proclaiming "a war to make the world safe for democracy." If they truly believed in their ideals, he explained, now was the time to fight. The question then became whether Americans would fight for what they deeply believed in, and the answer turned out to be a resounding "Yes". Some of this attitude was mobilised by the Spirit of 1917, which evoked the Spirit of '76.

Antiwar activists at the time and in the 1930s, alleged that beneath the veneer of moralism and idealism there must have been ulterior motives. Some suggested a conspiracy on the part of New York City bankers holding $3 billion of war loans to the Allies, or steel and chemical firms selling munitions to the Allies. The interpretation was popular among left-wing Progressives (led by Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin) and among the "agrarian" wing of the Democratic party—including the chairman of the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee of the House. He strenuously opposed war, and when it came he rewrote the tax laws to make sure the rich paid the most. (In the 1930s neutrality laws were passed to prevent financial entanglements from dragging the nation into a war.) In 1915, Bryan thought that Wilson's pro-British sentiments had unduly influenced his policies, so he became the first Secretary of State ever to resign in protest.

However, historian Harold C. Syrett demonstrated that business in general supported neutrality. Other historians state that the pro-war element was animated not by profit but by disgust with what Germany actually did, especially in Belgium, and the threat it represented to US ideals. Belgium kept the public's sympathy as the Germans executed civilians, and English nurse

GovTrack

/ref>

United States Senate The declaration passed in the

online edition

* Brands, H.W. ''Theodore Roosevelt'' (2001), full biography * Clements, Kendrick A. "Woodrow Wilson and World War I," ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 34:1 (2004). * Clifford, J. Garry. ''Citizen Soldiers: The Plattsburgh Training Camp Movement, 1913–1920'' (1972) * Cooper, John Milton. ''The vanity of power: American isolationism and the First World War, 1914–1917'' (1969). * Cooper, John Milton. ''Woodrow Wilson. A Biography'' (2009), Major scholarly biography. * Costrell, Edwin. ''How Maine viewed the war, 1914–1917,'' (1940) * Crighton, John C. ''Missouri and the World War, 1914–1917: a study in public opinion'' (University of Missouri, 1947) * Coffman, Edward M. ''The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I'' (1998) * Cummins, Cedric Clisten. ''Indiana public opinion and the World War, 1914–1917,'' (1945) * Davis, Allen F. ''American Heroine: The Life and Legend of Jane Addams.'' (Oxford University Press, 1973) * Doenecke, Justus D. ''Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America's Entry into World War I'' (2011) 433 pages; comprehensive history * Esposito, David M. ''The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson: American War Aims in World War I. '' (Praeger, 1996) 159pp * Finnegan, John P. ''Against the Specter of a Dragon: The Campaign for American Military Preparedness, 1914–1917.'' (1975). * Floyd, M. Ryan (2013). ''Abandoning American Neutrality: Woodrow Wilson and the Beginning of the Great War, August 1914 – December 1915.'' New York: Palgrave Macmillan. * Fordham, Benjamin O. "Revisionism reconsidered: exports and American intervention in World War I." ''International Organization'' 61#2 (2007): 277–310. * Grubbs, Frank L. ''The Struggle for Labor Loyalty: Gompers, the A. F. of L., and the Pacifists, 1917–1920.'' 1968. * Hannigan, Robert E. ''The Great War and American Foreign Policy, 1914–24'' (2016

* Hodgson, Godfrey. ''Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House.'' 2006. 335pp * Keene, Jennifer D. "Americans Respond: Perspectives on the Global War, 1914–1917." ''Geschichte und Gesellschaft'' 40.2 (2014): 266–286

online

* Kennedy, David M. ''Over Here: The First World War and American Society'' (1982), covers politics & economics & society * Kennedy, Ross A. "Preparedness," in Ross A. Kennedy ed., ''A Companion to Woodrow Wilson'' 2013. pp. 270–86 * Kennedy, Ross A. ''Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and America’s Strategy for Peace and Security'' (2009). * Koistinen, Paul. ''Mobilizing for Modern War: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1865–1919'' Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997. * Knock, Thomas J. ''To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order'' New York : Oxford University Press, 1992. * Lemnitzer, Jan Martin. "Woodrow Wilson’s Neutrality, the Freedom of the Seas, and the Myth of the 'Civil War Precedents'." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 27.4 (2016): 615–638. * Link, Arthur S. ''Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917''. 1972. * Link, Arthur S. ''Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality: 1914–1915'' (1960); ''Wilson: Confusions and Crises: 1915–1916'' (1964); ''Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916–1917'' (1965

all 3 volumes are online at ACLS e-books

* Link, Arthur S. ''Wilson the Diplomatist: A Look at His Major Foreign Policies'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1957. * Link, Arthur S. ''Woodrow Wilson and a Revolutionary World, 1913–1921''. 1982. * Link, Arthur S. ''Woodrow Wilson: Revolution, War, and Peace''. Arlington Heights, IL: AHM Pub. Corp., 1979. * Livermore, Seward W. ''Politics Is Adjourned: Woodrow Wilson and the War Congress, 1916–1918.'' 1966. * McCallum, Jack. ''Leonard Wood: Rough Rider, Surgeon, Architect of American Imperialism''. New York : New York University Press, 2006. * McDonald, Forrest. ''Insull: The Rise and Fall of a Billionaire Utility Tycoon'' (2004) * May, Ernest R. ''The World War and American Isolation, 1914–1917'' (1959

online at ACLS e-books

highly influential study * Nash, George H. ''Life of Herbert Hoover: The Humanitarian, 1914–1917'' (Life of Herbert Hoover, Vol. 2) (1988) * O'Toole, Patricia. ''When Trumpets Call: Theodore Roosevelt after the White House.'' New York : Simon & Schuster, 2005. * Perkins, Bradford. ''The Great Rapprochement: England and the United States, 1895–1914'' 1968. * Peterson, H. C. ''Propaganda for War: The Campaign Against American Neutrality, 1914–1917.'' Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968. * * Rothwell, V. H. ''British War Aims and Peace Diplomacy, 1914–1918.'' 1971. * Safford, Jeffrey J. ''Wilsonian Maritime Diplomacy, 1913–1921.'' 1978. * Smith, Daniel. ''The Great Departure: The United States and World War I, 1914–1920''. 1965. * Sterba, Christopher M. ''Good Americans: Italian and Jewish Immigrants during the First World War.'' 2003. 288 pp. * * Tucker, Robert W. ''Woodrow Wilson and the Great War: Reconsidering America's Neutrality, 1914–1917''. 2007. * Venzon, Anne Cipriano, ed. ''The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia'' New York: Garland Pub., 1995. * Ward, Robert D. "The Origin and Activities of the National Security League, 1914–1919." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 47 (1960): 51–65

online at JSTOR

online

* * Herman, Sondra. ''Eleven Against War: Studies in American Internationalist Thought, 1898–1921.'' (1969). * Hershey, Burnet. ''The Odyssey of Henry Ford and the Great Peace Ship'' (Taplinger Publishing, 1967). * Kazal, Russell A. ''Becoming Old Stock: The Paradox of German-American Identity.'' 2004. 390, pp. German Americans in Philadelphia ponder the war. * Kazin, Michael. ''War Against War: The American Fight for Peace, 1914–1918'' (2017). * Kelly, Andrew. "Film as Antiwar Propaganda: Lay Down Your Arms (1914)." ''Peace & Change'' 16.1 (1991): 97-112. * Kennedy, Kathleen. "Declaring war on war: Gender and the American socialist attack on militarism, 1914–1918." ''Journal of Women's History'' 7.2 (1995): 27-51

excerpt

* McKillen, Elizabeth. "Pacifist Brawn and Silk-Stocking Militarism: Labor, Gender, and Antiwar Politics, 1914–1918." ''Peace & Change'' 33.3 (2008): 388-425. * Luebke, Frederick C. ''Bonds of Loyalty: German-Americans and World War I.'' Dekalb : Northern Illinois University Press, 1974. * Steigerwald, Alison Rebecca. "Women United Against War: American Female Peace Activists’ Work During the First World War, 1914–1917' (PhD dissertation, The University of Iowa, 2020

online

* Unger, Nancy C. ''Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer'' (University of North Carolina Press, 2000). * Wachtell, Cynthia. ''War No More: The Antiwar Impulse in American Literature, 1861–1914'' (Louisiana State University Press, 2010). * Witcover, Jules. ''Sabotage at Black Tom: Imperial Germany's Secret War in America''. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1989. * Zeiger, Susan. "The schoolhouse vs. the armory: US teachers and the campaign against militarism in the schools, 1914–1918." ''Journal of Women's History'' 15.2 (2003): 150-179

online

free download

full coverage for major countries. * Doenecke, Justus D. "Neutrality Policy and the Decision for War." in Ross Kennedy ed., ''A Companion to Woodrow Wilson'' (2013) pp. 243–6

Online

covers the historiography * Higham, Robin and Dennis E. Showalter, eds. ''Researching World War I: A Handbook''. 2003. , 475pp; highly detailed historiography, * Keene, Jennifer D. "Remembering the "Forgotten War": American Historiography on World War I." ''Historian'' 78#3 (2016): 439–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/hisn.12245 * Keene, Jennifer D. "Finding a place for World War I in American history. 1914 –2018.

online

* Keene, Jennifer D. “Finding a Place for World War I in American History: 1914-2018.” In ''Writing the Great War: The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present,'' edited by Christoph Cornelissen and Arndt Weinrich, (Berghahn Books, 2020) pp.449–487.

online

840pp

edited by Arthur S. Link complete in 69 vol, at major academic libraries. Annotated edition of all of WW's letters, speeches and writings plus many letters written to him

Wilson, Woodrow. ''Why We Are at War'' (1917)

six war messages to Congress, Jan- April 1917 * Stark, Matthew J. "Wilson and the United States Entry into the Great War" ''OAH Magazine of History '' (2002) 17#1 pp. 40–47 lesson plan and primary sources for school project

online

United States of America

in

* Ford, Nancy Gentile

Civilian and Military Power (USA)

in

* Strauss, Lon

Social Conflict and Control, Protest and Repression (USA)

in

* Little, Branden

Making Sense of the War (USA)

in

* Miller, Alisa

Press/Journalism (USA)

in

* Wells, Robert A.

Propaganda at Home (USA)

in

* [https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/big/0402.html#article NY Times main headline, April 2, 1917, ''President Calls for War Declaration, Stronger Navy, New Army of 500,000 Men, Full Cooperation With Germany's Foes''] * S:President Wilson's War Address, President Wilson's War Address

Map of Europe

at the time of the US declaration of war on Germany at omniatlas.com

World War I: Declarations of War from Around the Globe – How America Entered the Great War

Today in History: U.S. Enters World War I

{{Woodrow Wilson United States in World War I United States home front during World War I Entry into World War I by country

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

entered into World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

on 6 April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began in Europe. Apart from an Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

In some cases, Anglophilia refers to an individual's appreciation of English history and traditional English cultural ico ...

element urging early support for the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and an anti-Tsarist element sympathizing with Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

's war against Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, American public opinion had generally reflected a desire to stay out of the war. Over time, especially after reports of German atrocities in Belgium in 1914 and after the sinking attack by the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

(U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

) torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

ing of the trans-Atlantic ocean liner off the southern coast of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

in May 1915, Americans increasingly came to see Imperial Germany as the aggressor in Europe.

While the country was at peace, American banks made huge loans to the Entente powers (Allies), which were used mainly to buy munitions, raw materials, and food from across the Atlantic in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

from the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. Although President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

made minimal preparations for a land war before 1917, he did authorize a shipbuilding program for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

. Wilson was narrowly re-elected in 1916 on an anti-war platform.

By 1917, with Belgium and Northern France occupied by German troops, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

experiencing turmoil and upheaval in the February revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

overthrowing the Czar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

on the Eastern Front, and with the remaining Entente Allied nations low on credit, the German Empire appeared to have the upper hand in Europe. However, a British economic embargo and naval blockade were causing severe shortages of fuel and food in Germany. Berlin then decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning. The use of unrestricted submarine warfare has had significant impacts on international relations in ...

. The aim was to break the trans-atlantic supply chain to Britain from other nations to the West, although the German high command realized that sinking American-flagged ships would almost certainly bring the United States into the war.

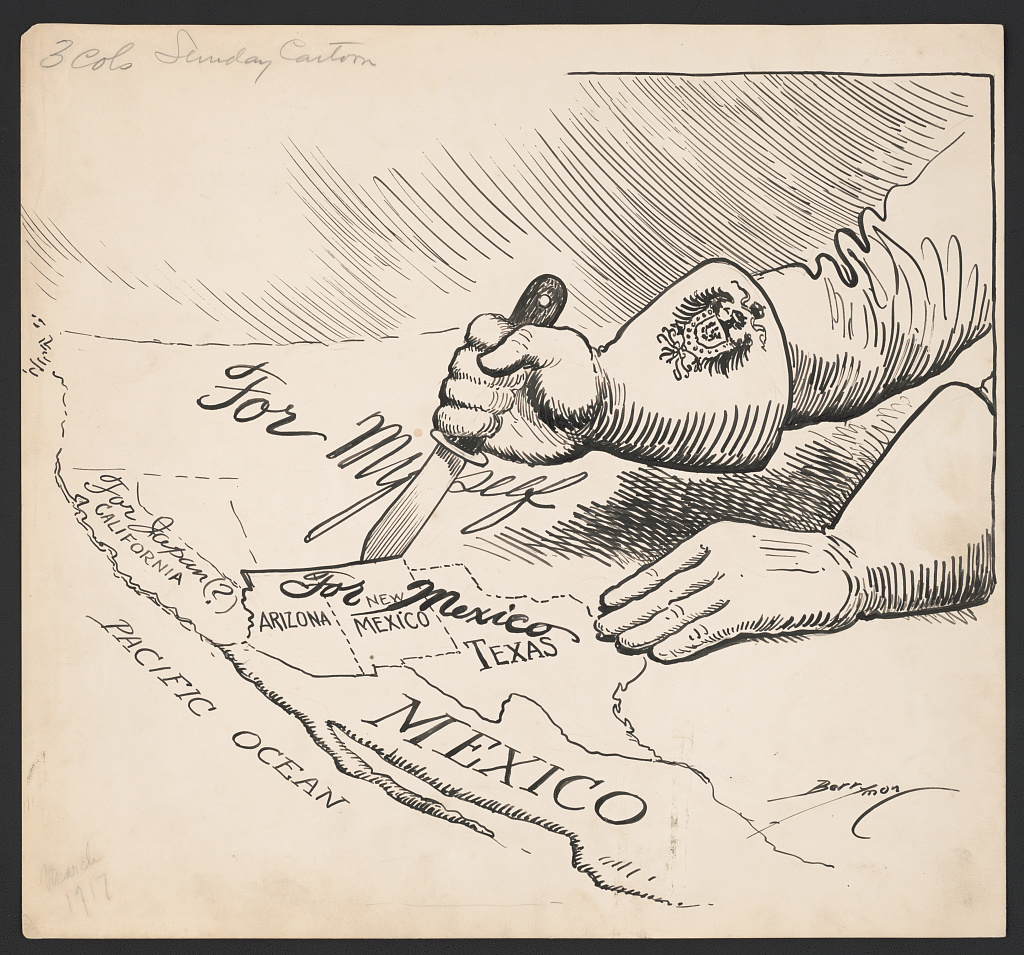

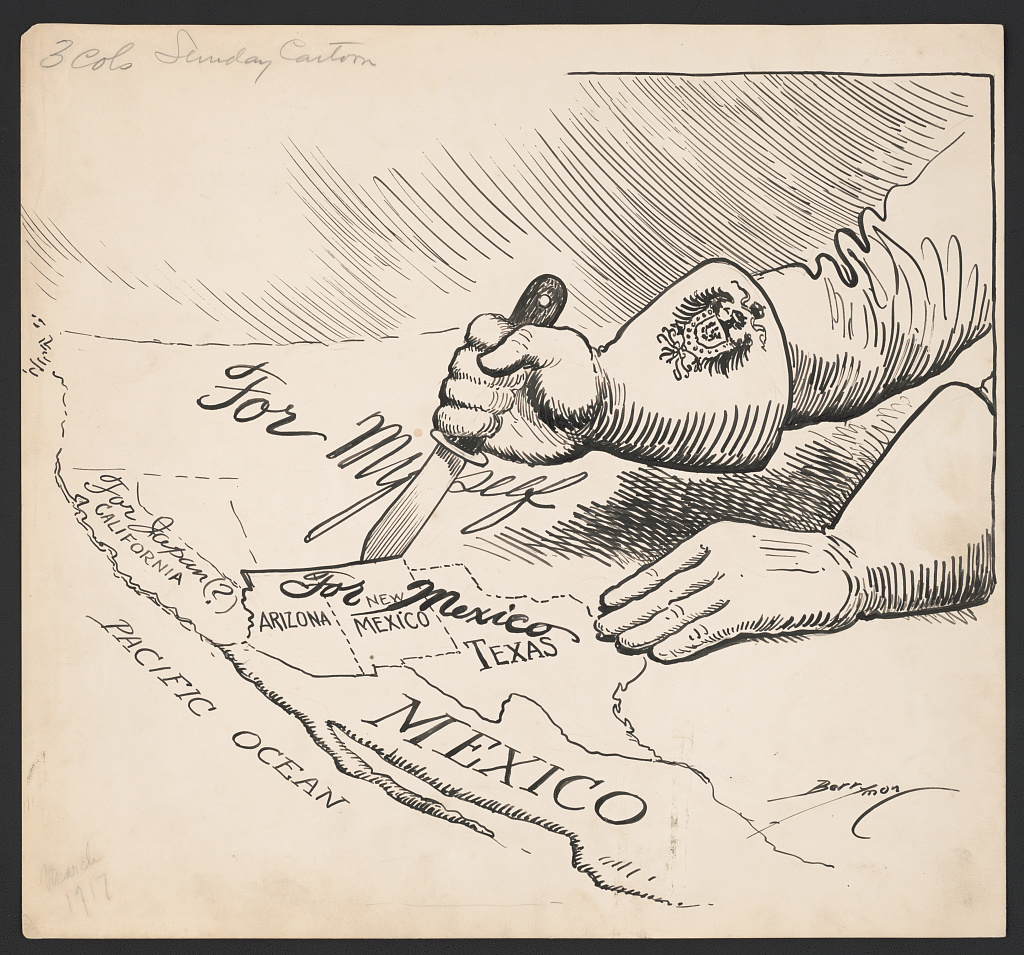

Imperial Germany also made a secret offer to help Mexico regain territories of the Mexican Cession

The Mexican Cession () is the region in the modern-day Western United States that Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United S ...

of 1849, lost seven decades before in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

of 1846–1848, (now incorporated in the Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

) in an encoded diplomatic secret telegram known as the Zimmermann Telegram, which was intercepted by British intelligence. Publication in the media of that communique outraged Americans just as German submarines

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or info ...

started sinking American merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

s in the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

in their U-boat campaign. President Wilson then asked Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

for "a war to end all wars" that would "make the world safe for democracy", and Congress voted to declare war on Germany on April 6, 1917. US troops began to arrive in Europe later that year, and served in major combat operations on the Western Front under the command of General John J. Pershing, particularly during the final Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Imperial Germa ...

.

Main issues

Naval blockade

Britain used its large navy to prevent cargo vessels entering German ports, mainly by intercepting them in the

Britain used its large navy to prevent cargo vessels entering German ports, mainly by intercepting them in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

between the coasts of Scotland and Norway. By the end of 1915, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

had successfully interdicted and stopped the naval shipment of most war supplies and food to Germany. Neutral American merchant cargo ships that tried to trade with Germany were seized or turned back by the Royal Navy in outlying waters who viewed such trade as in direct conflict with the Allies' war efforts. The impact from the blockade became apparent very slowly because Germany and its allies controlled extensive farmlands and raw materials on the continent of Europe and could trade with land-bordering neutral countries like Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

who were not themselves blockaded by the British or French. However, because Germany and adjacent Central Powers ally Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

had decimated their agricultural production by drafting and taking so many farmers and supplies of nitrate fertilisers into their armies, and the Allies were able to pressure neutral countries into reducing exports, the situation worsened, with the so-called "turnip winter

The Turnip Winter (, ) of 1916 to 1917 was a period of profound civilian hardship in German Empire, Germany during World War I.

Introduction

For the duration of World War I, Germany was constantly under threat of starvation due to the success ...

" of 1916–1917 an example of the emerging severe shortages in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

. The situation at the start of 1917 was such that there was clear pressure on the German leadership to avoid a "war of exhaustion", while the softening of neutral trade reduced the importance to keep the neutral countries on side.

Germany, for her part, had considered a blockade from 1914. "England wants to starve us", said Grand Admiral

Grand admiral is a historic naval rank, the highest rank in the several European navies that used it. It is best known for its use in Germany as . A comparable rank in modern navies is that of admiral of the fleet.

Grand admirals in individual ...

Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (; born Alfred Peter Friedrich Tirpitz; 19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral and State Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperi ...

(1849–1930), the man who built the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

fleet after 1871 with the unification of Germany

The unification of Germany (, ) was a process of building the first nation-state for Germans with federalism, federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without Habsburgs' multi-ethnic Austria or its German-speaking part). I ...

during the last few decades and who remained a key advisor to the German Emperor / Kaiser Wilhelm II. "We can play the same game. We can bottle her up and destroy every ship that endeavors to break the blockade". Admiral Tirpitz wanted to sink or scare off merchant and passenger ships en route to Britain. He and others in the Admiralty reasoned that since the island of Britain depended on imports of food, raw materials, and manufactured goods, preventing a substantial number of ships from supplying Britain would effectively undercut its long-term ability to maintain an army on the Western Front and potentially force Britain into speedy surrender. Such strategy would also give an essential, war winning role to the German Imperial Navy, who had been mostly passive in the war thus far due to being unable to challenge the powerful Royal Navy surface warship fleet.

While Germany had ample shipyard capacity to build hundreds of U-boats, they had only nine long-range U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s at the start of the war in August 1914. Nevertheless, without consulting colleagues earlier superiors like Tirpitz, the outgoing head of the German Admiralty Hugo von Pohl (1855–1916), declared the beginning of the first round of unrestricted submarine warfare six months after the war began in February 1915. However, instead of ceasing shipping to Britain and blaming the British (as the Germans positioned the move as a reprisal) as the Germans anticipated, the United States demanded that Germany respect the earlier peace-time international agreements upon "freedom of the seas

Freedom of the seas is a principle in the law of the sea. It stresses freedom to navigate the oceans. It also disapproves of war fought in water. The freedom is to be breached only in a necessary international agreement.

This principle was on ...

", which protected neutral American and other ships on the high seas from seizure or sinking by either belligerent. Furthermore, Americans insisted on strict accountability for the deaths of innocent American civilians, demanding an apology, compensation and suggesting that it is grounds for a declaration of war.

While the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

frequently violated America's neutral rights by defining contraband very broadly in their naval blockade of Germany, German submarine warfare threatened American lives. Wilson's top advisor, legendary Colonel Edward M. House (1858–1938), commented that, "The British have gone as far as they possibly could in violating neutral rights, though they have done it in the most courteous way". Further, while the British justified their argument with an appeal to precedent, the Germans claimed that they should be allowed to use their new weapon to its best potential and so existing rules and norms need not apply. This is especially exemplified when German submarines torpedoed ships without warning, causing sailors and passengers to drown. Though in practice this was initially rare, since U-boats preferred to attack on the surface, this strategy was justified by claims that submarines were so vulnerable that they dared not surface near merchant ships that might be carrying guns and which were too small to rescue submarine crews. The Americans countered that if the new weapon cannot be used while protecting civilian lives, it should not be used at all.

From February 1915, despite the United States warning Germany about the misuse of submarines, several incidents occurred where neutral ships were attacked or Americans killed. After the Thrasher incident, the German Imperial Embassy warned US citizens against boarding vessels to Britain, which would have to face German attack. Then on May 7, Germany torpedoed the British ocean liner ''RMS Lusitania

RMS ''Lusitania'' was a United Kingdom, British ocean liner launched by the Cunard Line in 1906. The Royal Mail Ship, the world's largest passenger ship until the completion of her sister three months later, in 1907 regained for Britain the ...

'', sinking her. This act of aggression caused the loss of 1,199 civilian lives, including 128 US citizens. The sinking of a large, unarmed passenger ship, combined with the previous stories of atrocities in Belgium, shocked Americans and turned public opinion hostile to Germany, although not yet to the point of war. Wilson issued a warning to Germany affirming it would face "strict accountability" if it killed more American citizens. Berlin acquiesced, ordering its submarines to avoid passenger ships.

By January 1917, however, Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

and General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (; 9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general and politician. He achieved fame during World War I (1914–1918) for his central role in the German victories at Battle of Liège, Liège and Battle ...

decided that an unrestricted submarine blockade was the only way to achieve a decisive victory. They demanded that Kaiser Wilhelm order unrestricted submarine warfare be resumed. Germany knew this decision meant war with the United States, but they gambled that they could win before the United States' potential strength could be mobilized. However, they overestimated how many ships they could sink and thus the extent Britain would be weakened. Finally, they did not foresee that convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s could and would be used to defeat their efforts. They believed that the United States was so weak militarily that it could not be a factor on the Western Front for more than a year and that submarines would stop the transport of troops anyway. The civilian government in Berlin objected, but the Kaiser sided with his military.

The second round of unrestricted submarine warfare was communicated to the Americans on January 31, 1917. The State Department had some indications that the campaign would come, but Wilson declared to his cabinet that the announcement had come as a complete surprise. The announcement was especially galling due to Wilson's "Peace without victory" speech nine days earlier, as well as ongoing discussions on US opposition to British use of armed merchant ships. The Germans started targeting American vessels the very next day.

Business considerations

The beginning of war in Europe coincided with the end of the Recession of 1913–1914 in the US. Exports to belligerent nations rose rapidly over the first four years of the War from $824.8 million in 1913 to $2.25 billion in 1917. Loans from American financial institutions to the Allied nations in Europe also increased dramatically over the same period. Economic activity towards the end of this period boomed as government resources aided the production of the private sector. Between 1914 and 1917, industrial production increased 32% and GNP increased by almost 20%. The improvements to industrial production in the United States outlasted the war. The capital build-up that had allowed US companies to supply belligerents and the US Army resulted in a greater long-run rate of production even after the war had ended in 1918. The J.P. Morgan Bank offered assistance in the wartime financing of Britain and France from the earliest stages of the conflict through the US's entrance in 1917. J.P. Morgan's New York office, was designated as the primary financial agent to the British government starting in 1914 after successful lobbying by the British ambassador, Sir Cecil Spring Rice. The same bank would later take a similar role in France. J.P. Morgan & Co. became the primary issuer of loans to the French government, providing the capital of US investors, operating from their French affiliate Morgan, Harjes. Relations between Morgan and the French government became tense as the war raged on with no end in sight however. France's ability to borrow from other sources diminished, leading to greater lending rates and a depressing of the value of the franc. After the war ended, J.P. Morgan & Co. continued to aid the French government financially through monetary stabilization and debt relief. Because the United States was still a declared neutral state, the financial dealings of United States banks in Europe caused a great deal of contention between Wall Street and the US Government. Secretary of StateWilliam Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

strictly opposed financial support of warring nations and wanted to ban loans to the belligerents in August 1914. He told President Wilson that "refusal to loan to any belligerent would naturally tend to hasten a conclusion of the war." Wilson at first agreed, but then reversed himself when France argued that if it was legal to buy US goods then it was legal to take out credits on the purchase.

J.P. Morgan issued loans to France including one in March 1915 and, following negotiations with the Anglo-French Financial Commission, another joint loan to Britain and France in October 1915, the latter amounting to US$500,000,000. Although the stance of the US government was that stopping such financial assistance could hasten the end of the war and therefore save lives, little was done to insure adherence to the ban on loans, in part due to pressure from Allied governments and US business interests.

The US steel industry had faced difficulties and declining profits during the Recession of 1913–1914. As war began in Europe, however, the increased demand for tools of war began a period of heightened productivity that alleviated many US industrial companies from the low-growth environment of the recession. Bethlehem Steel

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was an American steelmaking company headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Until its closure in 2003, it was one of the world's largest steel-producing and shipbuilding companies. At the height of its success ...

took particular advantage of the increased demand for armaments abroad. Prior to US entrance into the war, these companies benefited from unrestricted commerce with sovereign customers abroad. After President Wilson issued his declaration of war, the companies were subjected to price controls created by the US Trade Commission in order to insure that the US armed forces would have access to the necessary armaments.

By the end of the war in 1918, Bethlehem Steel had produced 65,000 pounds of forged military products and 70 million pounds of armor plate, 1.1 billion pounds of steel for shells, and 20.1 million rounds of artillery ammunition for Britain and France. Bethlehem Steel took advantage of the domestic armaments market and produced 60% of the US weaponry and 40% of the artillery shells used in the war. Even with price controls and a lower profit margin on manufactured goods, the profits resulting from wartime sales expanded the company into the third largest manufacturing company in the country. Bethlehem Steel became the primary arms supplier for the United States and other allied powers again in 1939.

Views of the elites

Historians divide the views of US political, social and business leaders into four distinct groupings—the camps were mostly informal: The first of these were the Non-Interventionists, a loosely affiliated and politically diverseanti-war movement

An anti-war movement is a social movement in opposition to one or more nations' decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term ''anti-war'' can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during con ...

which sought to keep the United States out of the conflict altogether. Members of this group tended to view the war as a clash between the imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

and militaristic great powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

of Europe, whom they deemed to be corrupt and unworthy of support. Others were pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

, who objected on moral grounds. Prominent leaders included Democrats like former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

, industrialist Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

and publisher William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

; Republicans such as Senator Robert M. La Follette

Robert Marion La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), nicknamed "Fighting Bob," was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th governor of Wisconsin from 1901 to 1906. ...

of Wisconsin and Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska; and Progressive activist Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

.

At the far-left

Far-left politics, also known as extreme left politics or left-wing extremism, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single, coherent definition; some ...

end of the political spectrum, the Socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

, led by their perennial candidate

A perennial candidate is a political candidate who frequently runs for elected office and rarely, if ever, wins. Perennial candidates are most common where there is no limit on the number of times that a person can run for office and little cost ...

for President, Eugene V. Debs, and movement veterans like Victor L. Berger and Morris Hillquit, were staunch anti-militarists. They were opposed to any US intervention, branding the conflict as a " capitalist war" that US workers should resist. However, after the US joined the war in April 1917, a schism developed between the anti-war party leadership and a pro-war faction of socialist writers and intellectuals led by John Spargo

John Spargo (January 31, 1876 – August 17, 1966) was a British political writer who, later in life, became an expert in the history and crafts of Vermont. At first Spargo was active in the Socialist Party of America. A Methodist preacher, he t ...

, William English Walling and E. Haldeman-Julius

Emanuel Haldeman-Julius (''né'' Emanuel Julius) (July 30, 1889 – July 31, 1951) was a American Jews, Jewish-American History of the socialist movement in the United States#20th century, socialist writer, atheist thinker, social reformer and pu ...

. This clique founded the rival Social Democratic League of America to promote the war effort among their fellow Socialists.

Next were the more moderate Liberal-Internationalists. This nominally- progressive group reluctantly supported US entry into the war against Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, with the postwar goal of establishing strong international institutions

An international organization, also known as an intergovernmental organization or an international institution, is an organization that is established by a treaty or other type of instrument governed by international law and possesses its own leg ...

designed to peacefully resolve future conflicts between nations and to promote liberal democratic

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal democracy are: ...

values more broadly. This camp's views were advocated by interest groups such as the League to Enforce Peace. Adherents included U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, his influential advisor Edward M. House, former President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

, chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium

The Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB, or simply Belgian Relief) was an international, predominantly American, organization that arranged for the supply of food to German-occupied Belgium and northern France during the First World War.

It ...

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

, Wall Street financier Bernard Baruch

Bernard Mannes Baruch (August 19, 1870 – June 20, 1965) was an American financier and statesman.

After amassing a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, he impressed President Woodrow Wilson by managing the nation's economic mobilization in W ...

and Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

President Abbott Lawrence Lowell

Abbott Lawrence Lowell (December 13, 1856 – January 6, 1943) was an American educator and legal scholar. He was president of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933.

With an "aristocratic sense of mission and self-certainty," Lowell cut a large ...

.

Finally, there were the Atlanticists. Politically conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

and unambiguously pro- Allied, this faction had championed US intervention in the war since the sinking of the ''Lusitania'' and also strongly supported the Preparedness Movement

The Preparedness Movement was a campaign led by former Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Leonard Wood, and former President Theodore Roosevelt to strengthen the United States Armed Forces, U.S. military af ...

. Proponents also advocated for an enduring postwar alliance with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, which they saw as vital to maintaining the future security of the US. Prominent among the Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

In some cases, Anglophilia refers to an individual's appreciation of English history and traditional English cultural ico ...

Eastern establishment, supporters included former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, Major General Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, List of colonial governors of Cuba, Military Governor of Cuba, ...

, lawyer and diplomat Joseph Hodges Choate

Joseph Hodges Choate (January 24, 1832 – May 14, 1917) was an American lawyer and diplomat. He was chairman of the American delegation at the Second Hague Conference, and ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Choate was associated with many of t ...

, former Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and Demo ...

and Senators Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

of Massachusetts and Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican Party (United States), Republican politician, and statesman who served as the 41st United States Secretary of War under presidents William McKinley and Theodor ...

of New York.

Public opinion

Parties

A surprising factor in the development of US public opinion was how little the political parties became involved. Wilson and the Democrats in 1916 campaigned on the slogan "He kept us out of war!", saying a Republican victory would mean war with both Mexico and Germany. His position probably was critical in winning the Western states.Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, the GOP candidate, insisted on downplaying the war issue.

The Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of America ...

talked peace. Socialist rhetoric declared the European conflict to be "an imperialist war" blaming the war on capitalism and pledged total opposition. "A bayonet", its propaganda said, "was a weapon with a worker at each end". When war was declared, however, many Socialists, including much of the party's intellectual leadership, supported the decision and sided with the pro-Allied efforts. The majority, led by Eugene V. Debs (the party's presidential candidate from 1900 to 1912), remained ideological and die-hard opponents. Many socialists came under investigation from the Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code ( ...

and many suspected of treason were arrested, including Debs. This increased the Socialists' and anti-war groups' resentment toward the US Government.

Workers, farmers, and African Americans

The working class was relatively quiet and tended to divide along ethnic lines. At the beginning of the war, neither working men nor farmers took a large interest in the debates on war preparation.Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, head of the AFL labor movement, denounced the war in 1914 as "unnatural, unjustified, and unholy", but by 1916 he was supporting Wilson's limited preparedness program, against the objections of Socialist union activists. In 1916 the labor unions supported Wilson on domestic issues and ignored the war question.

The war at first disrupted the cotton market; the Royal Navy blockaded shipments to Germany, and prices fell from 11 cents a pound to only 4 cents. By 1916, however, the British decided to bolster the price to 10 cents to avoid losing Southern support. The cotton growers seem to have moved from neutrality to intervention at about the same pace as the rest of the nation. Midwestern farmers generally opposed the war, especially those of German and Scandinavian descent. The Midwest became the stronghold of isolationism; other remote rural areas also saw no need for war.

The African-American community did not take a strong position one way or the other. A month after Congress declared war, W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

called on African-Americans to "fight shoulder to shoulder with the world to gain a world where war shall be no more". Once the war began and black men were drafted, they worked to achieve equality. Many had hoped the community's help in the war efforts abroad would earn civil rights at home. When such civil liberties were still not granted, many African-Americans grew tired of waiting for recognition of their rights as American citizens.

South

There was a strong antiwar element among poor rural whites in the South and border states. In rural Missouri for example, distrust of powerful Eastern influences focused on the risk that Wall Street would lead the US into war. Across the South poor white farmers warned each other that "a rich man's war meant a poor man's fight," and they wanted nothing of it. Antiwar sentiment was strongest among Christians affiliated with the Churches of Christ, the Holiness movement and Pentecostal churches. CongressmanJames Hay James Hay may refer to:

* James Hay (bishop) (died 1538), Scottish abbot and bishop

* James Hay, 7th Lord Hay of Yester (1564–1609), Scottish landowner and courtier

* James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle (c.1580–1636), British noble

* James Hay, 2nd ...

, Democrat of Virginia was the powerful chairman of the House Committee on Military Affairs. He repeatedly blocked prewar efforts to modernize and enlarge the army. Preparedness was not needed because Americans were already safe, he insisted in January 1915:

: Isolated as we are, safe in our vastness, protected by a great navy, and possessed of an army sufficient for any emergency that may arise, we may disregard the lamentations and predictions of the militarists.

Educated, urban, middle-class southerners generally supported entering the war, and many worked on mobilization committees. In contrast to this many rural southern whites opposed entering the war. Those with more formal education were more in favor of entering the war and those in the south with less formal education were more likely to oppose entering the war. Letters to newspapers with spelling or grammatical errors were overwhelmingly letters which opposed entry into the war, whereas letters with no spelling or grammatical errors were overwhelming those which supported entry into the war. When the war began Texas and Georgia led the southern states with volunteers. 1,404 from Texas, 1,397 from Georgia, 538 from Louisiana, 532 from Tennessee, 470 from Alabama, 353 from North Carolina, 316 from Florida, and 225 from South Carolina. Every southern Senator voted in favor of entering the war except for Mississippi firebrand James K. Vardaman. By coincidence, there were some regions of the south which were more heavily in favor of intervention than others. Georgia provided the most volunteers per capita out of any state in the union before conscription and had the highest portion of pro-British newspapers before the US entry into the war. There were five competing newspapers which covered the region of Southeast Georgia, all of whom were outspokenly Anglophilic during the decades preceding the war, and during the early phases of the war. All five of which also highlighted German atrocities during the rape of Belgium

The Rape of Belgium was a series of systematic war crimes, especially mass murder and German occupation of Belgium during World War I#Deportation and forced labour, deportation, by German troops against Belgians, Belgian civilians during Germa ...

and the execution of Edith Cavell

Edith Louisa Cavell ( ; 4 December 1865 – 12 October 1915) was a British nurse. She is celebrated for treating wounded soldiers from both sides without discrimination during the First World War and for helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape ...

. Other magazines with nationwide distribution which were pro-British such as

The Outlook and The Literary Digest

''The Literary Digest'' was an American general interest weekly magazine published by Funk & Wagnalls. Founded by Isaac Kaufmann Funk in 1890, it eventually merged with two similar weekly magazines, ''Public Opinion'' and '' Current Opinion''. ...

had a disproportionately high distribution throughout every region of the state of Georgia as well as the region of northern Alabama in the area around Huntsville and Decatur (when the war began there were 470 volunteers from the state of Alabama, of these, over 400 came from Huntsville-Decatur region).

Support for US entry into the war was also pronounced in central Tennessee. Letters to newspapers which expressed pro-British, anti-German or pro-interventionist sentiment were common. In between October 1914 and April 1917, letters about the war to newspapers from Tennessee included at least one of these three sentiments. In the Tennessee counties of Cheatham County, Robertson County, Sumner County, Wilson County, Rutherford County, Williamson County, Maury County, Marshall County, Bedford County, Coffee County and Cannon County over half of the letters contained all three of these elements. In South Carolina there was support for the US entering the war. Led by Governor Richard I. Manning, the cities of Greenville, Spartanburg, and Columbia had started lobbying for army training centers in their communities, for both economic and patriotic reasons, in preparation for US entry into the war. Similarly, Charleston had interned a German freighter in 1914, and when the freighter's skeleton crew tried to block Charleston harbor they were all arrested and imprisoned. From that point on Charleston was buzzing with "war fever." 1915, 1916 and early 1917 were all years when Charleston and the low country coastal counties to the south of Charleston, were all gripped by sentiment that was very "pro-British and anti-German."

German Americans

German Americans

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

by this time usually had only weak ties to Germany; however, they were fearful of negative treatment they might receive if the United States entered the war (such mistreatment was already happening to German-descent citizens in Canada and Australia). Almost none called for intervening on Germany's side, instead calling for neutrality and speaking of the superiority of German culture. As more nations were drawn into the conflict, however, the English-language press increasingly supported Britain, while the German-American media called for neutrality while also defending Germany's position. Chicago's Germans worked to secure a complete embargo on all arms shipments to Europe. In 1916, large crowds in Chicago's Germania celebrated the Kaiser's birthday, something they had not done before the war. German Americans in early 1917 still called for neutrality, but proclaimed that if a war came they would be loyal to the United States. By this point, they had been excluded almost entirely from national discourse on the subject. German-American Socialists in Milwaukee

Milwaukee is the List of cities in Wisconsin, most populous city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Located on the western shore of Lake Michigan, it is the List of United States cities by population, 31st-most populous city in the United States ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

actively campaigned against entry into the war.

Christian churches and pacifists

Leaders of most religious groups (except the Episcopalians) tended to pacifism, as did leaders of the woman's movement. The Methodists and Quakers among others were vocal opponents of the war. President Wilson, who was a devout Presbyterian, would often frame the war in terms of good and evil in an appeal for religious support of the war.

A concerted effort was made by pacifists including

Leaders of most religious groups (except the Episcopalians) tended to pacifism, as did leaders of the woman's movement. The Methodists and Quakers among others were vocal opponents of the war. President Wilson, who was a devout Presbyterian, would often frame the war in terms of good and evil in an appeal for religious support of the war.

A concerted effort was made by pacifists including Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

, Oswald Garrison Villard

Oswald Garrison Villard (March 13, 1872 – October 1, 1949) was an American journalist and editor of the ''New York Evening Post.'' He was a civil rights activist, and along with his mother, Fanny Villard, a founding member of the NAACP. In ...

, David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan (January 19, 1851 – September 19, 1931) was the founding president of Stanford University, serving from 1891 to 1913. He was an ichthyologist during his research career. Prior to serving as president of Stanford Universi ...

, Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

, Lillian Wald

Lillian D. Wald (March 10, 1867 – September 1, 1940) was an American nurse, humanitarian and author. She strove for human rights and started American community nursing. She founded the Henry Street Settlement in New York City and was an early ...

, and Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (born Carrie Clinton Lane; January 9, 1859#Fowler, Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women t ...

. Their goal was to encourage Wilson's efforts to mediate an end of the war by bringing the belligerents to the conference table. Finally in 1917 Wilson convinced some of them that to be truly anti-war they needed to support what he promised would be "a war to end all wars".

Once war was declared, the more liberal denominations, which had endorsed the Social Gospel

The Social Gospel is a social movement within Protestantism that aims to apply Christian ethics to social problems, especially issues of social justice such as economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, racial tensions, slums, unclean en ...

, called for a war for righteousness that would help uplift all mankind. The theme—an aspect of American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief that the United States is either distinctive, unique, or exemplary compared to other nations. Proponents argue that the Culture of the United States, values, Politics of the United States, political system ...

—was that God had chosen America as his tool to bring redemption to the world.

US Catholic bishops maintained a general silence toward the issue of intervention. Millions of Catholics lived in both warring camps, and Catholic Americans tended to split on ethnic lines in their opinions toward US involvement in the war. At the time, heavily Catholic towns and cities in the East and Midwest often contained multiple parishes, each serving a single ethnic group, such as Irish, German, Italian, Polish, or English. US Catholics of Irish and German descent opposed intervention most strongly. Pope Benedict XV made several attempts to negotiate a peace. All of his efforts were rebuffed by both the Allies and the Germans, and throughout the war the Vatican maintained a policy of strict neutrality.

Jewish Americans

In 1914–1916, there were fewJewish Americans

American Jews (; ) or Jewish Americans are Americans, American citizens who are Jews, Jewish, whether by Jewish culture, culture, ethnicity, or Judaism, religion. According to a 2020 poll conducted by Pew Research, approximately two thirds of Am ...

in favor of US entry into the war. New York City, with its Jewish community numbering 1.5 million, was a center of antiwar activism, much of which was organized by labor unions which were primarily on the political left and therefore opposed to a war that they viewed to be a battle between several great powers.

Some Jewish communities worked together during the war years to provide relief to Jewish communities in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

which were decimated by fighting, famine and scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy of destroying everything that allows an enemy military force to be able to fight a war, including the deprivation and destruction of water, food, humans, animals, plants and any kind of tools and i ...

policies of the Russian and Austro-German armies.

Of greatest concern to Jewish Americans was the Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

ist government in Russia due its toleration of pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s and allegedly following antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

policies. As historian Joseph Rappaport reported through his study of Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

press during the war, "The pro-Germanism of America's immigrant Jews was an inevitable consequence of their Russophobia

Anti-Russian sentiment or Russophobia is the dislike or fear of Russia, Russian people, or Russian culture. The opposite of Russophobia is Russophilia.

Historically, Russophobia has included state-sponsored and grassroots mistreatment and di ...

." However, after the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...