Ulster Nationalism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

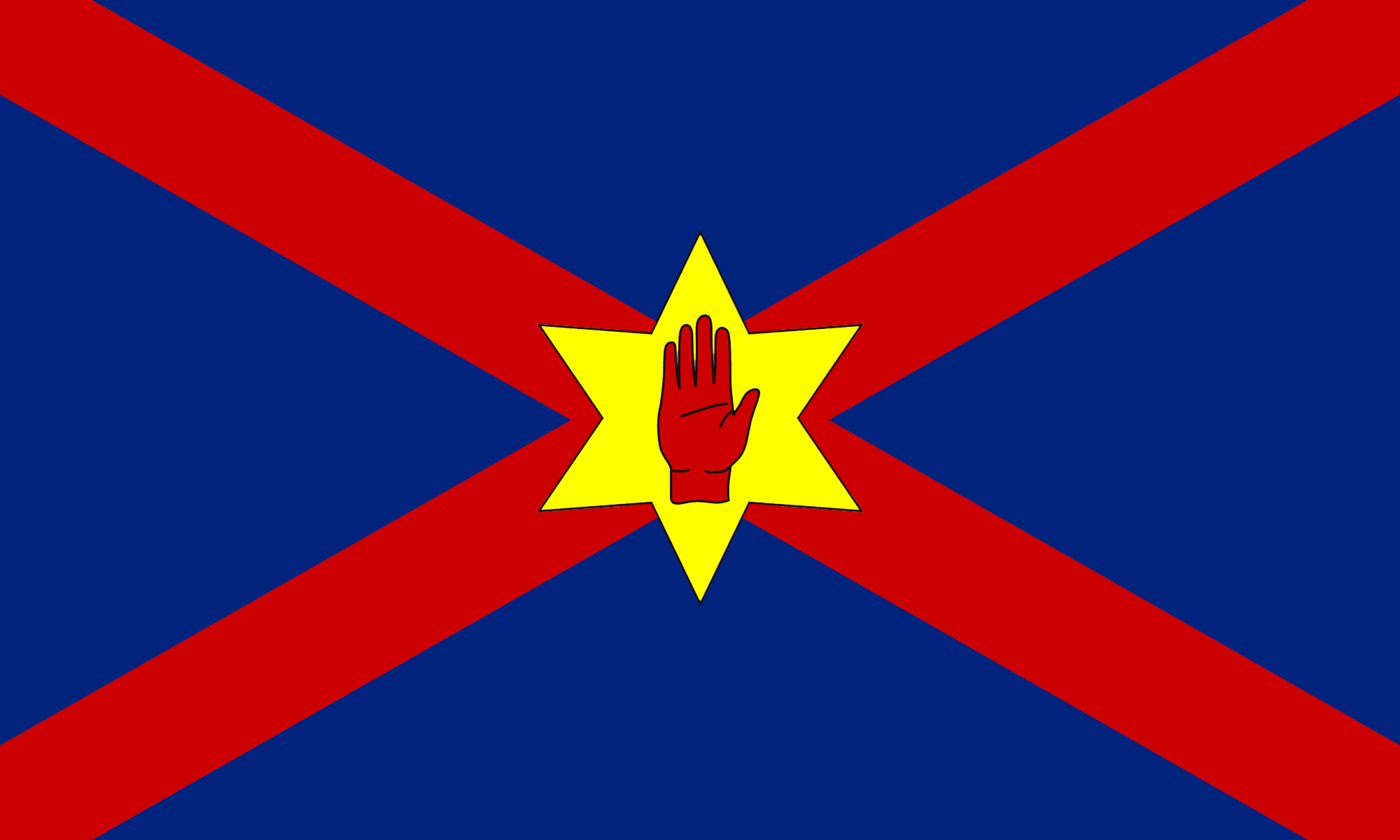

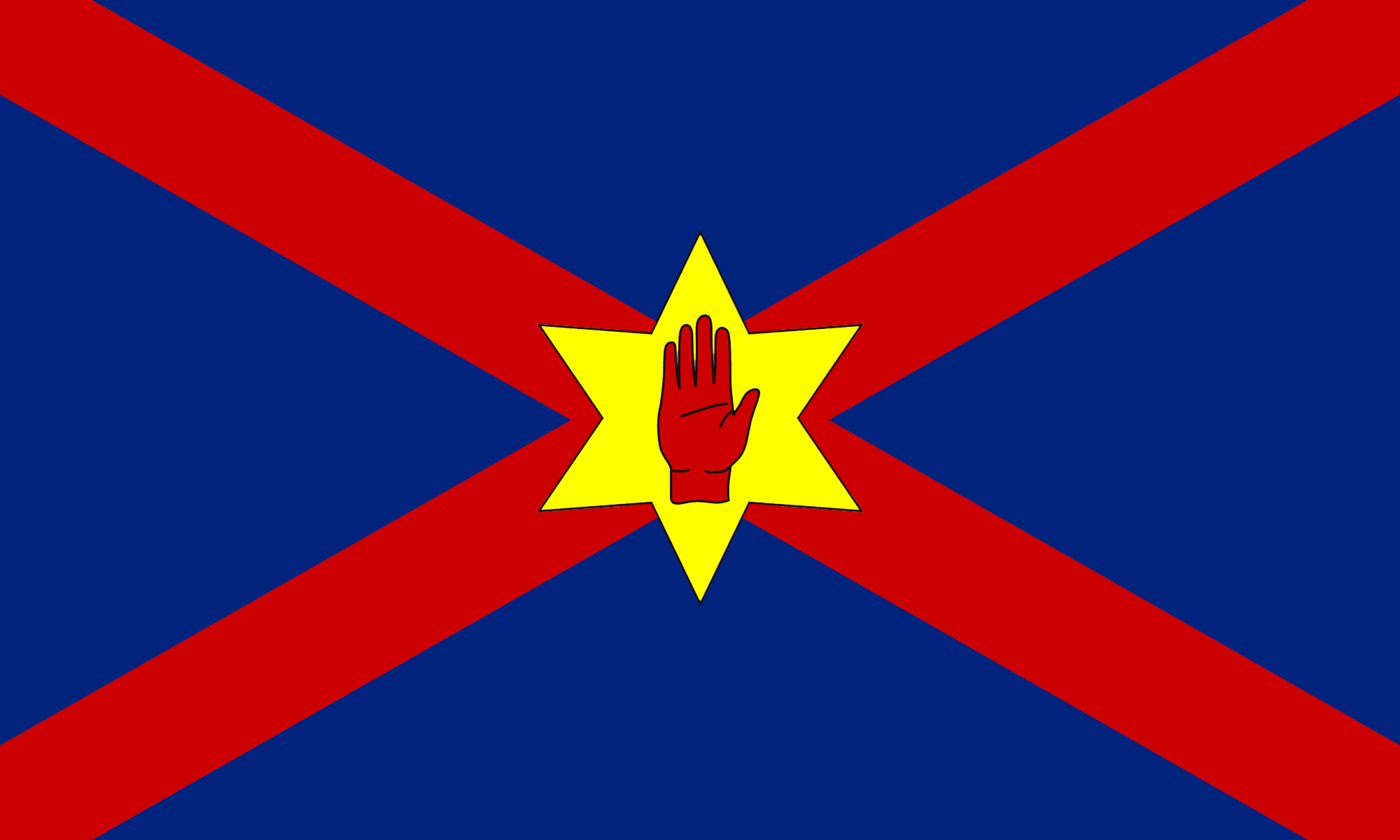

Ulster nationalism is a minor school of thought in the politics of Northern Ireland that seeks the independence of

Ulster nationalism is a minor school of thought in the politics of Northern Ireland that seeks the independence of

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the

Ulster Nation

{{Ulster Defence Association Separatism in the United Kingdom Independence movements Politics of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

without joining the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

, thereby becoming an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in Pennsylvania, United States

* Independentes (English: Independents), a Portuguese artist ...

sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

separate from both.

Independence has been supported by groups such as Ulster Third Way and some factions of the Ulster Defence Association. However, it is a fringe view in Northern Ireland. It is neither supported by any of the political parties represented in the Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly (; ), often referred to by the metonym ''Stormont'', is the devolved unicameral legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliam ...

nor by the government of the United Kingdom

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

or the government of the Republic of Ireland.

Although the term Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

traditionally refers to one of the four traditional provinces of Ireland

There are four provinces of Ireland: Connacht, Leinster, Munster and Ulster. The Irish language, Irish word for this territorial division, , meaning "fifth part", suggests that there were once five, and at times Kingdom of Meath, Meath has be ...

which contains Northern Ireland as well as parts of the Republic of Ireland, the term is often used within unionism and Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Unionism in Ireland, Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland (and formerly all of I ...

(from which Ulster nationalism originated) to refer to Northern Ireland.

History

Craig in 1921

In November 1921, during negotiations for theAnglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, there was correspondence between David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

and Sir James Craig, respective prime ministers of the UK and Northern Ireland. Lloyd George envisaged a choice for Northern Ireland between, on the one hand, remaining part of the UK under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, while what had been Southern Ireland became a Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

; and, on the other hand, becoming part of an all-Ireland Dominion where the Stormont parliament was subordinate to a parliament in Dublin instead of Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

. Craig responded that a third option would be for Northern Ireland to be a Dominion in parallel with Southern Ireland and the "Overseas Dominions", saying "while Northern Ireland would deplore any loosening of the tie between Great Britain and herself she would regard the loss of representation at Westminster as a less evil than inclusion in an all-Ireland Parliament".

W. F. McCoy and Dominion status

Ulster nationalism has its origins in 1946 when W. F. McCoy, a former cabinet minister in thegovernment of Northern Ireland

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

, advocated this option. He wanted Northern Ireland to become a dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

with a political system similar to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

and the then Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

, or the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

prior to 1937. McCoy, a lifelong member of the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a Unionism in Ireland, unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded as the Ulster Unionist Council in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it l ...

, felt that the uncertain constitutional status of Northern Ireland made the Union vulnerable and so saw his own form of limited Ulster nationalism as a way to safeguard Northern Ireland's relationship with the United Kingdom.

Some members of the Ulster Vanguard movement, led by Bill Craig, in the early 1970s published similar arguments, most notably Professor Kennedy Lindsay. In the early 1970s, in the face of the British government prorogation of the government of Northern Ireland, Craig, Lindsay and others argued in favour of a unilateral declaration of independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) or "unilateral secession" is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the ...

(UDI) from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

similar to that declared in Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

a few years previously. Lindsay later founded the British Ulster Dominion Party to this end but it faded into obscurity around 1979.

Loyalism and Ulster nationalism

Whilst early versions of Ulster nationalism had been designed to safeguard the status of Northern Ireland, the movement saw something of a rebirth in the 1970s, particularly following the 1972 suspension of the Parliament of Northern Ireland and the resulting political uncertainty in the region. Glenn Barr, a Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party Assemblyman and Ulster Defence Association leader, described himself in 1973 as "an Ulster nationalist". The successful Ulster Workers Council Strike in 1974 (which was directed by Barr) was later described by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Merlyn Rees as an "outbreak of Ulster nationalism". Labour Prime Minister Jim Callaghan also thought an independent Northern Ireland might be viable. After the strike loyalism began to embrace Ulster nationalist ideas, with the UDA, in particular, advocating this position. Firm proposals for an independentUlster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

were produced in 1976 by the Ulster Loyalist Central Co-ordinating Committee and in 1977 by the UDA's New Ulster Political Research Group. The NUPRG document, ''Beyond the Religious Divide'', has been recently republished with a new introduction. John McMichael, as candidate for the UDA-linked Ulster Loyalist Democratic Party, campaigned for the 1982 South Belfast by-election on the basis of negotiations towards independence. However, McMichael's poor showing of 576 votes saw the plans largely abandoned by the UDA soon after, although the policy was still considered by the Ulster Democratic Party under Ray Smallwoods. A short-lived Ulster Independence Party also operated, although the assassination of its leader, John McKeague, in 1982 saw it largely disappear.

Post-Anglo-Irish Agreement

The idea enjoyed something of a renaissance in the aftermath of the Anglo-Irish Agreement, with the Ulster Clubs amongst those to consider the notion. After a series of public meetings, leading Ulster Clubs member, Reverend Hugh Ross, set up the Ulster Independence Committee in 1988, which soon re-emerged as the Ulster Independence Movement advocating full independence of Northern Ireland from Britain. After a reasonable showing in the 1990 Upper Bann by-election, the group stepped up its campaigning in the aftermath of the Downing Street Declaration and enjoyed a period of increased support immediately after the Good Friday Agreement (also absorbing the Ulster Movement for Self-Determination, which desired all ofUlster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

as the basis for independence, along the way). No tangible electoral success was gained however, and the group was further damaged by allegations against Ross in a Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by Channel Four Television Corporation. It is state-owned enterprise, publicly owned but, unlike the BBC, it receives no public funding and is funded en ...

documentary on collusion, ''The Committee'', leading to the group reconstituting as a ginger group

The Ginger Group was not a formal political party in Canada, but a faction of radical Progressive and Labour Members of Parliament who advocated socialism. The term ginger group also refers to a small group with new, radical ideas trying to ...

in 2000.

With the UIM defunct, Ulster nationalism was then represented by the Ulster Third Way, which was involved in the publication of the ''Ulster Nation'', a journal of radical Ulster nationalism. Ulster Third Way, which registered as a political party in February 2001, was the Northern Ireland branch of the UK-wide Third Way

The Third Way is a predominantly centrist political position that attempts to reconcile centre-right and centre-left politics by advocating a varying synthesis of Right-wing economics, right-wing economic and Left-wing politics, left-wing so ...

, albeit with much stronger emphasis on the Northern Ireland question. Ulster Third Way contested the West Belfast parliamentary seat in the 2001 general election, although candidate and party leader David Kerr failed to attract much support.

Northern Irish independence is still seen by some members of society as a way of moving forward in terms of the political crisis that continues to haunt Northern Irish politics even today. Some economists and politicians see an independent state as viable but others believe that Northern Ireland would not survive unless it had the support of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

or the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

. Although it is not supported by a political party, around 533,085 declared in the 2011 census to be Northern Irish

The people of Northern Ireland are all people born in Northern Ireland and having, at the time of their birth, at least one parent who is a British Nationality Law, British citizen, an Irish nationality law, Irish citizen or is otherwis ...

. This identity does not mean they believe in independence, however in a poll based upon what the future policy for Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

should be, 15% of the poll voters were in favour of Northern Irish independence.

Relationship to unionism

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the

Ulster nationalism represents a reaction from within unionism to the perceived uncertainty of the future of the Union by the British government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

. Its leadership and members have all been unionists and have tended to react to what they viewed as crises surrounding the status of Northern Ireland as a part of the United Kingdom, such as the moves towards power-sharing in the 1970s or the Belfast Agreement of 1998, which briefly saw the UIM become a minor force. In such instances it has been considered preferable by the supporters of this ideological movement to remove the British dimension either partially (Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations that has the same constitutional monarch and head of state as the other realms. The current monarch is King Charles III. Except for the United Kingdom, in each of the re ...

status) or fully (independence) to avoid a united Ireland

United Ireland (), also referred to as Irish reunification or a ''New Ireland'', is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically: the sovereign state of Ireland (legally ...

.

However, whilst support for Ulster nationalism has tended to be reactive to political change, the theory also underlines the importance of Ulster cultural nationalism and the separate identity and culture of Ulster. As such, Ulster nationalist movements have been at the forefront of supporting the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

and supporting contested 12 July marches as important parts of this cultural heritage, as well as encouraging the retention of the Ulster Scots dialects

Ulster Scots or Ulster-Scots (), also known as Ulster Scotch and Ullans, is the dialect (whose proponents assert is a dialect of Scots language, Scots) spoken in parts of Ulster, being almost exclusively spoken in parts of Northern Ireland a ...

.

Outside traditional Protestant-focused Ulster nationalism, a non-sectarian independent Northern Ireland has sometimes been advocated as a solution to the conflict. Two notable proponents of this are the Scottish Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

Tom Nairn and the Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

Liam de Paor.

See also

* Cornish nationalism * English independence * Scottish independence *Two nations theory (Ireland)

In Ireland, the two nations theory holds that Ulster Protestants form a distinct Irish nation.''Where is the Irish Border? Theories of Division in Ireland'', by Sean Swan, Nordic Ireland Studies, 2005, pp. 61–87. Advocated mainly by Unionis ...

*Unionism in Ireland

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition that professes loyalty to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, crown of the United Kingdom and to the union it represents with England, Scotland and Wales. The overwhelming sentiment of Ireland's Pro ...

* Welsh independence

References

Sources

*Citations

External links

*Ulster Nation

{{Ulster Defence Association Separatism in the United Kingdom Independence movements Politics of Northern Ireland