USFC Grampus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USFC ''Grampus'' was a

USFC ''Grampus'' was a

/ref> ''Grampus''′s

/ref> ''Grampus'' was constructed to fill a need the Fish Commission perceived for a ship with a well in which

In addition to meeting the Fish Commissions research and

In addition to meeting the Fish Commissions research and

''Grampus''′s

''Grampus''′s

The Fish Commission commissioned ''Grampus'' on 5 June 1886 under the command of

The Fish Commission commissioned ''Grampus'' on 5 June 1886 under the command of  The voyage doubled as a

The voyage doubled as a  From April through July 1888, ''Grampus'' returned to the mackerel fishing grounds between Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras, collecting living eggs and embryos for fish-culture work and experimenting successfully with returning living mackerel to port in her well. In May 1888, she also studied

From April through July 1888, ''Grampus'' returned to the mackerel fishing grounds between Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras, collecting living eggs and embryos for fish-culture work and experimenting successfully with returning living mackerel to port in her well. In May 1888, she also studied

''Grampus'' completed her cod collection duties off Massachusetts for the season in May 1890. From 3 July to 25 August 1890, she resumed the work of recording water temperatures and weather off southern

''Grampus'' completed her cod collection duties off Massachusetts for the season in May 1890. From 3 July to 25 August 1890, she resumed the work of recording water temperatures and weather off southern

By an

By an

Inactive over the winter of 1909–1910, ''Grampus'' began her annual lobster collection duties in April 1910. She conducted her routine fish-culture work during fiscal year 1911 (1 July 1910-30 June 1911) and fiscal year 1912 (1 July 1911–30 June 1912). In July and August 1912, she explored the

Inactive over the winter of 1909–1910, ''Grampus'' began her annual lobster collection duties in April 1910. She conducted her routine fish-culture work during fiscal year 1911 (1 July 1910-30 June 1911) and fiscal year 1912 (1 July 1911–30 June 1912). In July and August 1912, she explored the

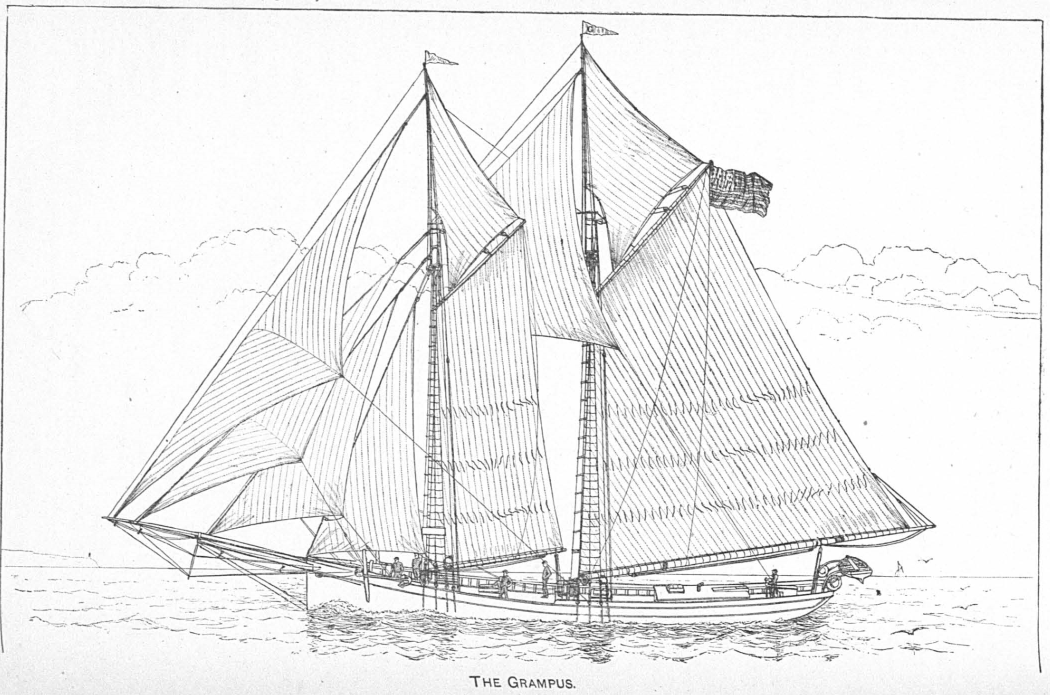

"U.S. Fish Commission Schooner Grampus, 1886

Report on the Construction and Equipment of the Schooner Grampus, taken from the Report of Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, 1886," noaa.gov, August 26, 2022 Accessed 18 March 2023

/ref>

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for 1886''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1889.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for 1887''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1891.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for 1888''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1892.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for 1889 to 1891''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1893.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1892''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1894.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1893''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1895.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1894''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1896.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1895''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1896.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1896''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1898.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1897''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1898.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1898''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1899.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1899''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1900.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1900''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1901.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1901''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1902.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1902''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1904.

United States Commission on Fish and Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1903''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1905.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1905 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1906 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1907 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1909.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1909 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1911.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1910 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1911.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1911 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1913.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1912 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1914.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1913 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1914.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1914 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1915.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1915 and Special Papers''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1917.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1916 with Appendixes''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1917.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1917 with Appendixes''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1919.

Bureau of Fisheries. ''Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries for the Fiscal Year 1918 with Appendixes''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1920.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Grampus Ships built in Groton, Connecticut 1886 ships Ships of the United States Bureau of Fisheries Schooners of the United States Two-masted ships Maritime incidents in November 1888 Maritime incidents in 1891 Shipwrecks of the Massachusetts coast

USFC ''Grampus'' was a

USFC ''Grampus'' was a fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life or, more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a., fishing grounds). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farm ...

research ship

A research vessel (RV or R/V) is a ship or boat designed, modified, or equipped to carry out research at sea. Research vessels carry out a number of roles. Some of these roles can be combined into a single vessel but others require a dedicated ...

in commission in the fleet of the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries, usually called the United States Fish Commission

The United States Fish Commission, formally known as the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries, was an agency of the United States government created in 1871 to investigate, promote, and preserve the Fishery, fisheries of the United St ...

, from 1886 to 1903 and then as USFS ''Grampus'' in the fleet of its successor, the United States Bureau of Fisheries

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

, until 1917. She was a schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

of revolutionary design in terms of speed and safety and influenced the construction of later commercial fishing

Commercial fishing is the activity of catching fish and other seafood for Commerce, commercial Profit (economics), profit, mostly from wild fisheries. It provides a large quantity of food to many countries around the world, but those who practice ...

schooners.NOAA History: Report On The Construction And Equipment Of The Schooner Grampus/ref> ''Grampus''′s

home port

A vessel's home port is the port at which it is based, which may not be the same as its port of registry shown on its registration documents and lettered on the stern of the ship's hull. In the cruise industry the term "home port" is also oft ...

s were Woods Hole

Woods Hole is a census-designated place in the town of Falmouth in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. It lies at the extreme southwestern corner of Cape Cod, near Martha's Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands. The population was 78 ...

and Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city, non-metropolitan district and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West England, South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. During her 31-year career, ''Grampus'' made significant contributions to the understanding of the mackerel

Mackerel is a common name applied to a number of different species of pelagic fish, mostly from the family Scombridae. They are found in both temperate and tropical seas, mostly living along the coast or offshore in the oceanic environment.

...

fishery off the United States East Coast

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, and the British colony of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

. She also investigated the tilefish

file:Malacanthus latovittatus.jpg, 250px, Blue blanquillo, ''Malacanthus latovittatus''

Tilefishes are mostly small perciform marine fish comprising the family (biology), family Malacanthidae. They are usually found in sandy areas, especially n ...

population, conducted fishery investigations in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

, and contributed to fish culture

Fish farming or pisciculture involves commercial breeding of fish, most often for food, in fish tanks or artificial enclosures such as fish ponds. It is a particular type of aquaculture, which is the controlled cultivation and harvesting of aquat ...

work in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

to propagate the mackerel, cod

Cod (: cod) is the common name for the demersal fish genus ''Gadus'', belonging to the family (biology), family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gad ...

, and lobster

Lobsters are Malacostraca, malacostracans Decapoda, decapod crustaceans of the family (biology), family Nephropidae or its Synonym (taxonomy), synonym Homaridae. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on th ...

.

Design

Fish Commission requirements

Fishery scientists of the late 19th century believed that successful spawning was the most significant factor in the productivity of fisheries, and the Fish Commission had placed the fisheries research ship USFC ''Fish Hawk'' in service in 1880 to serve as a floatingfish hatchery

A fish hatchery is a place for artificial breeding, hatching, and rearing through the early life stages of animals—finfish and shellfish in particular.Crespi V., Coche A. (2008) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Gloss ...

that could move up and down the coast in accordance with the timing of American shad

The American shad (''Alosa sapidissima'') is a species of anadromous clupeid fish naturally distributed on the North American coast of the North Atlantic, from Newfoundland to Florida, and as an introduced species on the North Pacific coast. T ...

runs.NOAA History: R/V Fish Hawk 1880-1926/ref> ''Grampus'' was constructed to fill a need the Fish Commission perceived for a ship with a well in which

marine fish

Saltwater fish, also called marine fish or sea fish, are fish that live in seawater. Saltwater fish can swim and live alone or in a large group called a school.

Saltwater fish are very commonly kept in aquariums for entertainment. Many saltwater ...

es could be kept alive and transported from the fishing grounds to fish hatcheries

A fish hatchery is a place for artificial breeding, Egg#Fish and amphibian eggs, hatching, and rearing through the early life stages of animals—finfish and shellfish in particular.Crespi V., Coche A. (2008) Food and Agriculture Organization of t ...

on the coast of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, where fisheries researchers could collect their eggs for use in the hatcheries and further ensure productive fisheries. ''Grampus'' also was to bring back fish for biological

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, and distribution of ...

study of the fish themselves.

''Grampus'' also needed to be seaworthy and fast, so as to be able to collect fish from Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an waters and bring back to the United States fish such as sole, turbot

The turbot ( ) ''Scophthalmus maximus'' is a relatively large species of flatfish in the family Scophthalmidae. It is a demersal fish native to marine or brackish waters of the Northeast Atlantic, Baltic Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. It is a ...

, plaice

Plaice is a common name for a group of flatfish that comprises four species: the European, American, Alaskan and scale-eye plaice.

Commercially, the most important plaice is the European. The principal commercial flatfish in Europe, it is ...

, and brill

Brill may refer to:

Places

* Brielle (sometimes "Den Briel"), a town in the western Netherlands

* Brill, Buckinghamshire, a village in England

* Brill, Cornwall, a small village to the west of Constantine, Cornwall, UK

* Brill, Wisconsin, an un ...

– which were important to the European commercial fishing industry but did not occur naturally in the waters off North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

– so that they could be introduced into waters off the United States. ''Grampus'' also was to demonstrate the method of beam trawl

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Radio beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially lo ...

ing used by European fishermen in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

but not in the United States at the time to catch groundfish

Demersal fish, also known as groundfish, live and feed on or near the bottom of seas or lakes (the demersal zone).Walrond Carl . "Coastal fish - Fish of the open sea floor"Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009 They oc ...

, and to spur the use of beam trawling by American commercial fishermen in the hope of increasing the monetary value of the American catch and to provide additional employment for men aboard American fishing vessels. The Fish Commission believed that groundfish species native to the waters off North America could be profitably fished even though they differed from the species found in European waters, and ''Grampus'' was to use beam trawling to test this idea.

The Fish Commission wanted to develop a comprehensive understanding of the migration of food fish

Many species of fish are caught by humans and consumed as food in virtually all regions around the world. Their meat has been an important dietary source of protein and other nutrients in the human diet.

The English language does not have a s ...

es in the spring and autumn as they travelled to and from their summer feeding grounds, and chose to construct ''Grampus'' as a sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on Mast (sailing), masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing Square rig, square-rigged or Fore-an ...

because it wanted her to be able to remain at sea for weeks or months at a time to follow the migration continuously and investigate it completely without having to come into port for coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

, as a steamer would. ''Grampus'' also had to be seaworthy enough to remain on duty and not lose contact with the migrating fish during bad weather. Finally, ''Grampus'' had to be designed and equipped to capture fish that did not swim near the surface in order to investigate fisheries completely, and she also needed to be able to capture and investigate minute life such as plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

, which supported the food fish population.

''Grampus'' needed a windlass

The windlass is an apparatus for moving heavy weights. Typically, a windlass consists of a horizontal cylinder (barrel), which is rotated by the turn of a crank or belt. A winch is affixed to one or both ends, and a cable or rope is wound arou ...

in order to work her gear, and the Fish Commission opted for a steam

Steam is water vapor, often mixed with air or an aerosol of liquid water droplets. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization. Saturated or superheated steam is inv ...

windlass. United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

Lieutenant Commander Zera Luther Tanner

Zera Luther Tanner (December 5, 1835 – December 16, 1906), sometimes spelled Zero, was an American naval officer, inventor, and oceanographer. Tanner invented a depth sounding system, wrote several books on hydrography and retired as a commande ...

, an influential inventor and oceanographer

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of top ...

of the era, commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or commander, or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually give ...

of the Fish Commissions fisheries research ship USFC ''Albatross'', and previously the first commanding officer of ''Fish Hawk'', received the task of determining what type of steam apparatus ''Grampus'' should carry. He chose a steam windlass with engines of 35 horsepower (26.1 kW). Operating the windlass required the installation of a boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

, steam pump, iron water tanks, and associated piping.

Speed and safety

fish culture

Fish farming or pisciculture involves commercial breeding of fish, most often for food, in fish tanks or artificial enclosures such as fish ponds. It is a particular type of aquaculture, which is the controlled cultivation and harvesting of aquat ...

requirements, ''Grampus''s design also reflected ideas for improvement in the design of the then-conventional New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

commercial fishing schooners so as to improve both speed and safety. In the mid-1880s, these schooners tended to be wide, shallow, and sharp so as to allow the greatest possible speed by reducing drag through the water and allowing the ship to carry a considerable amount of sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

. In order to keep the hulls shallow, the schooners were "very wide aft, with a heavy, clumsy stern and fat counters, the run being hollowed out excessively so as to produce in the after section a series of very abrupt horizontal curves." The two masts came to nearly the same height above the waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water.

A waterline can also refer to any line on a ship's hull that is parallel to the water's surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed position. Hence, wate ...

, and the schooners carried a large jib

A jib is a triangular sail that sets ahead of the foremast of a sailing vessel. Its forward corner (tack) is fixed to the bowsprit, to the bows, or to the deck between the bowsprit and the foremost mast. Jibs and spinnakers are the two main ty ...

extending from the bowsprit

The bowsprit of a sailing vessel is a spar (sailing), spar extending forward from the vessel's prow. The bowsprit is typically held down by a bobstay that counteracts the forces from the forestay, forestays. The bowsprit’s purpose is to create ...

end to the foremast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the median line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, giving necessary height to a navigation light ...

.

This traditional schooner design had a number of drawbacks. The shallow hull did not, in fact, contribute significantly to speed, and the wide stern design actually hindered fast sailing. The ships shallowness of hull gave them a high center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the barycenter or balance point) is the unique point at any given time where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. For ...

that made them prone to capsizing and sinking in heavy seas, often with significant or total loss of life among their crews. The foremast rising to the same height as the mainmast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the median line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, giving necessary height to a navigation light ...

often meant either that the jib when raised to the top of the foremast caused an inefficient, asymmetrical sail pattern, or that the upper parts of the foremast were left unused; having a foremast that was taller than necessary added extra expense to the cost of the ships construction and also meant that she had an unnecessary amount of weight aloft, making her less stable and more prone to dangerous rolling and capsizing. The large jib also created problems, moving the sails center of effort too far forward when the schooner shortened sail and the mainsail was reefed, making the ship harder to handle. Moreover, handling the large jib required crew members to work on the bowsprit in bad weather, a dangerous practice that resulted in men being swept overboard and drowned.

To address these issues, ''Grampus'', although similar in design to the traditional New England schooner, also differed in significant ways. She had a hull Commissioner's Report 1901, p. 324. deeper than traditional schooners of similar length, giving her greater stability, and her beam was less than that of a traditional schooner. She had a straight stem, rather than a raking one, and her stern was narrower and more raked, with her after portion approximating a V-shape, all changes which increased her hull length at the waterline. Her foremast was considerably shorter than her mainmast, and her rigging was designed so that she could carry a double-headed rig forward that allowed her to use a smaller jib that could be furled upon the approach of heavy weather and a fore staysail running from the foremast to near her stem. The result was a ship able to achieve higher sailing speeds, able to make more efficient use of her sails, with no need for crew members to work on her bowsprit during bad weather, and less likely to capsize in heavy seas.

Ideas for the changes in schooner design to make these improvements had been discussed as early as 1882, but ''Grampus''s design was the first to put them into practice. A model of ''Grampus'' went on display in 1885 at the American Fish Bureau in Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city, non-metropolitan district and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West England, South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, and attracted much attention. Her design influenced that of many future commercial fishing schooners. The U.S. Fish Commission′s ''Report of the Commissioner for the Year Ending June 30, 1901'' said that "her superiority in safety, speed, and other desirable qualities has been fully established" and " ter twelve years' service .e., through at least 1898the ''Grampus'' is unexcelled in speed by fishing vessel

A fishing vessel is a boat or ship used to fishing, catch fish and other valuable nektonic aquatic animals (e.g. shrimps/prawns, krills, coleoids, etc.) in the sea, lake or river. Humans have used different kinds of surface vessels in commercial ...

s or pilot boat

A pilot boat is a type of boat used to transport maritime pilots between land and the inbound or outbound ships that they are piloting. Pilot boats were once sailing boats that had to be fast because the first pilot to reach the incoming ship ...

s. Referring to shipbuilding in New England, the report added, "Nearly all of the fishing vessels recently built are deeper than formerly, and embody other features that characterize the ''Grampus''. The spirit of improvement has received such an impetus that the best skill of the most eminent naval architect This is the top category for all articles related to architecture and its practitioners.

{{Commons category, Architecture by occupation

Design occupations

Occupations

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's rol ...

s has of late been devoted to designing fishing vessels."

Other characteristics

''Grampus'' was of wooden construction, built largely ofwhite oak

''Quercus'' subgenus ''Quercus'' is one of the two subgenera into which the genus ''Quercus'' was divided in a 2017 classification (the other being subgenus ''Cerris''). It contains about 190 species divided among five sections. It may be calle ...

with some white pine

''Pinus'', the pines, is a genus of approximately 111 extant tree and shrub species. The genus is currently split into two subgenera: subgenus ''Pinus'' (hard pines), and subgenus ''Strobus'' (soft pines). Each of the subgenera have been further ...

deck planking. She was in length overall

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and is also ...

. Her fish well was pyramidal in shape, long and about wide at the bottom and long and about wide at the top, and it had 204 holes in its bottom planks to allow seawater

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximat ...

to circulate through it. A laboratory was situated just aft of the well;Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 456–457. it contained closet space and shelving to hold specimens in jars of alcohol, medicines, the ship′s library of over 100 volumes,Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 456. fishing gear, and signal gun equipment. The ship was equipped to store specimens on ice.

For fishing, ''Grampus'' was rigged for trawling

Trawling is an industrial method of fishing that involves pulling a fishing net through the water behind one or more boats. The net used for trawling is called a trawl. This principle requires netting bags which are towed through water to catch di ...

, hand-line fishing, gillnetting

Gillnetting is a fishing method that uses gillnets: vertical panels of netting that hang from a line with regularly spaced floaters that hold the line on the surface of the water. The floats are sometimes called "corks" and the line with corks is ...

, seining, dredging

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing d ...

, and squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

jigging

Jigging is the practice of fishing with a jig, a type of weighted fishing lure. A jig consists of a heavy metals, heavy metal (typically lead) fishing sinker, sinker with an attached fish hook that is usually obscured inside a soft plastic bai ...

.Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 485. She had equipment for capturing the eggs of pelagic fishes and keeping the eggs alive or hatching them once they were aboard. She also was equipped to harpoon

A harpoon is a long, spear-like projectile used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other hunting to shoot, kill, and capture large fish or marine mammals such as seals, sea cows, and whales. It impales the target and secures it with barb or ...

swordfish

The swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as the broadbill in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are the sole member of the Family (biology), family Xiphiidae. They ...

and porpoise

Porpoises () are small Oceanic dolphin, dolphin-like cetaceans classified under the family Phocoenidae. Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals and Beluga whale, belugas than to the Oceanic dolphi ...

s, with a pulpit for this purpose mounted on her jib

A jib is a triangular sail that sets ahead of the foremast of a sailing vessel. Its forward corner (tack) is fixed to the bowsprit, to the bows, or to the deck between the bowsprit and the foremost mast. Jibs and spinnakers are the two main ty ...

boom end. She carried guns with which her personnel could shoot bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s and seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

so that their carcasses could be collected for study. To collect environmental information, she carried sounding equipment and deep-sea thermometers.

sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

suit consisted of a foresail

A foresail is one of a few different types of sail set on the foremost mast (''foremast'') of a sailing vessel:

* A fore-and-aft sail set on the foremast of a schooner or similar vessel.

* The lowest square sail on the foremast of a full-rigged ...

, a fore staysail

A staysail ("stays'l") is a fore-and-aft rigged sail whose luff can be affixed to a stay running forward (and most often but not always downwards) from a mast to the deck, the bowsprit, or to another mast.

Description

Most staysails a ...

, a riding sail, a mainsail

A mainsail is a sail rigged on the main mast (sailing), mast of a sailing vessel.

* On a square rigged vessel, it is the lowest and largest sail on the main mast.

* On a fore-and-aft rigged vessel, it is the sail rigged aft of the main mast. T ...

, a jib

A jib is a triangular sail that sets ahead of the foremast of a sailing vessel. Its forward corner (tack) is fixed to the bowsprit, to the bows, or to the deck between the bowsprit and the foremost mast. Jibs and spinnakers are the two main ty ...

, a flying jib

A jib is a triangular sail that sets ahead of the foremast of a sailing vessel. Its forward corner ( tack) is fixed to the bowsprit, to the bows, or to the deck between the bowsprit and the foremost mast. Jibs and spinnakers are the two mai ...

, a fore gaff

Gaff may refer to:

Ankle-worn devices

* Spurs in variations of cockfighting

* Climbing spikes used to ascend wood poles, such as utility poles

Arts and entertainment

* A character in the ''Blade Runner'' film franchise

* Penny gaff, a 19th- ...

topsail

A topsail ("tops'l") is a sail set above another sail; on square-rigged vessels further sails may be set above topsails.

Square rig

On a square rigged vessel, a topsail is a typically trapezoidal shaped sail rigged above the course sail and ...

, a main gaff topsail, a main topmast

The masts of traditional sailing ships were not single spars, but were constructed of separate sections or masts, each with its own rigging. The topmast is one of these.

The topmast is semi-permanently attached to the upper front of the lower m ...

staysail, and a balloon jib. She carried five boats: a carvel-built

Carvel built or carvel planking is a method of boat building in which hull planks are laid edge to edge and fastened to a robust frame, thereby forming a smooth surface. Traditionally the planks are neither attached to, nor slotted into, each ...

seiner

A fishing vessel is a boat or ship used to fishing, catch fish and other valuable nektonic aquatic animals (e.g. shrimps/prawns, krills, coleoids, etc.) in the sea, lake or river. Humans have used different kinds of surface vessels in commercial ...

rigged as a schooner; a carvel-built open dinghy

A dinghy is a type of small boat, often carried or Towing, towed by a Watercraft, larger vessel for use as a Ship's tender, tender. Utility dinghies are usually rowboats or have an outboard motor. Some are rigged for sailing but they diffe ...

rigged as a sloop; and three dories. She also carried three "live-cars," dory-like craft covered with heavy netting through which seawater could circulate freely. They were intended to keep fish alive after crew members manning the dories hauled in trawl

Trawling is an industrial method of fishing that involves pulling a fishing net through the water behind one or more boats. The net used for trawling is called a trawl. This principle requires netting bags which are towed through water to catch di ...

lines; the men in the dories could dump the live fish into a live-car alongside each dory as they reeled in the lines.

Construction

By the spring of 1885, theUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

had appropriated $14,000 (USD

The United States dollar (symbol: $; currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introduced the U.S. dollar at par with the Spanish silver dollar, divided it int ...

) for the design and construction of ''Grampus'' and design of the ship began. Under the supervision of U.S. Fish Commission Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

J. W. Collins,Commissioner's Report 1901, p. 323. ''Grampus''s hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

was constructed at Noank

Noank ( ) is a village in the town of Groton, Connecticut. This dense community of historic homes and local businesses sits on a small, steep peninsula at the mouth of the Mystic River and has a long tradition of fishing, lobstering, and boat-bui ...

, Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

, by Robert Palmer & Sons, which launched her on 23 March 1886. Her sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

s, rigging

Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support and control a sailing ship or sail boat's masts and sails. ''Standing rigging'' is the fixed rigging that supports masts including shrouds and stays. ''Running rigg ...

, blocks, and ground tackle

A mooring is any permanent structure to which a seaborne vessel (such as a boat, ship, or amphibious aircraft) may be secured. Examples include quays, wharfs, Jetty, jetties, piers, anchor buoys, and mooring buoys. A ship is secured to a moori ...

came from E. L. Rowe & Son, of Gloucester; her boats from Higgins & Gifford, of Gloucester; her steam

Steam is water vapor, often mixed with air or an aerosol of liquid water droplets. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization. Saturated or superheated steam is inv ...

windlass

The windlass is an apparatus for moving heavy weights. Typically, a windlass consists of a horizontal cylinder (barrel), which is rotated by the turn of a crank or belt. A winch is affixed to one or both ends, and a cable or rope is wound arou ...

from the American Ship Windlass Company of Providence

Providence often refers to:

* Providentia, the divine personification of foresight in ancient Roman religion

* Divine providence, divinely ordained events and outcomes in some religions

* Providence, Rhode Island, the capital of Rhode Island in the ...

, Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

; and the boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

for the windlass from M. V. B. Darling of Providence. The rest of her equipment came mainly from Bliss Brothers and H. M. Greenough of Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, Massachusetts.

Service history

U.S. Fish Commission

1880s

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

J. W. Collins. She departed Noank that day for Woods Hole

Woods Hole is a census-designated place in the town of Falmouth in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. It lies at the extreme southwestern corner of Cape Cod, near Martha's Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands. The population was 78 ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

,Commissioner′s Report 1886, p. xlviiCommissioner's Report 1886, p. 701. which was to be her home port

A vessel's home port is the port at which it is based, which may not be the same as its port of registry shown on its registration documents and lettered on the stern of the ship's hull. In the cruise industry the term "home port" is also oft ...

. After a stopover at Woods Hole from 6 to 8 June 1886, she departed for Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city, non-metropolitan district and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West England, South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean ...

, Massachusetts, where she arrived on 9 June 1886 and took aboard her boats and fishing gear – all of which had been manufactured at Gloucester – and made alterations to her sails. That work completed, she sailed on 14 June 1886 to Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, Massachusetts, where she took aboard her marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), and the time at t ...

and "other instruments and apparatus." She spent 16–22 June 1886 at Gloucester, then sailed to Woods Hole, arriving there on 23 June 1886 to begin preparations for her first scientific cruise.

That cruise began on 21 August 1886, when ''Grampus'' departed Woods Hole to determine the status of the tilefish

file:Malacanthus latovittatus.jpg, 250px, Blue blanquillo, ''Malacanthus latovittatus''

Tilefishes are mostly small perciform marine fish comprising the family (biology), family Malacanthidae. They are usually found in sandy areas, especially n ...

off Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the U.S. state of Massachusetts, lying just south of Cape Cod. It is known for being a popular, affluent summer colony, and includes the smaller peninsula Chappaquiddick Isla ...

, Massachusetts.Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 702. Discovered in 1879, first collected scientifically at sea by the Fish Commission steamer in 1880, and abundant enough in 1880 and 1881 to suggest the development of a new fishery, the tilefish had experienced a massive die-off in 1882, with many millions of dead fish found between Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck Island, Tuckernuck and Muskeget Island, Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and Co ...

, Massachusetts, and Cape May

Cape May consists of a peninsula and barrier island system in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is roughly coterminous with Cape May County and runs southwards from the New Jersey mainland, separating Delaware Bay from the Atlantic Ocean. Th ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

. After a week on the fishing grounds without finding a single tilefishCommissioner's Report 1886, p. 703. – prompting Collins to propose that the species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

was at least locally extinct – ''Grampus'' set course for Woods Hole, arriving there on 24 August 1886.

The voyage doubled as a

The voyage doubled as a shakedown cruise

Shakedown cruise is a nautical term in which the performance of a ship is tested. Generally, shakedown cruises are performed before a ship enters service or after major changes such as a crew change, repair, refit or overhaul. The shakedown ...

, and it demonstrated that the steam windlass and its engines and boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centra ...

were too heavy for ''Grampus'', adding so much weight forward as to make her difficult to manage in a seaway, and the windlass and its associated machinery were removed and placed ashore at Woods Hole.The Fish Commission steamer took the steam windlass aboard at Woods Hole on 13 September 1886 and transported it to Providence

Providence often refers to:

* Providentia, the divine personification of foresight in ancient Roman religion

* Divine providence, divinely ordained events and outcomes in some religions

* Providence, Rhode Island, the capital of Rhode Island in the ...

, Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

, where the American Ship Windlass Company installed it aboard ''Fish Hawk'' between 14 and 26 September 1886. (See Commissioner's Report 1886, p. 696.) She therefore arrived at Gloucester on 2 September 1886 to have installed a new wooden windlass that had been manufactured for her there. With her new windlass installed, she departed Gloucester on 22 September for a cruise to La Have Bank and Roseway Bank in the North Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

south of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, and Seal Island Ground in the Gulf of Maine

The Gulf of Maine is a large gulf of the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of North America. It is bounded by Cape Cod at the eastern tip of Massachusetts in the southwest and by Cape Sable Island at the southern tip of Nova Scotia in the northea ...

to collect live cod

Cod (: cod) is the common name for the demersal fish genus ''Gadus'', belonging to the family (biology), family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gad ...

and halibut

Halibut is the common name for three species of flatfish in the family of right-eye flounders. In some regions, and less commonly, other species of large flatfish are also referred to as halibut.

The word is derived from ''haly'' (holy) and ...

for return to Woods Hole for study and propagation, i.e., fish culture

Fish farming or pisciculture involves commercial breeding of fish, most often for food, in fish tanks or artificial enclosures such as fish ponds. It is a particular type of aquaculture, which is the controlled cultivation and harvesting of aquat ...

work. During the cruise, ''Grampus'' received a "perfect specimen" of the squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

'' Sthenoteuthis megaptera'' – only the second perfect specimen of the species ever collected and the first in United States, preceded only by one collected in Canada – from the Gloucester-based schooner ''Mabel Leighton'' on 26 September 1886. She had little success in her primary objective, finding that cod and halibut caught in deep water died soon after being placed in her well, apparently because of the rapid change in pressure and temperature as they were hauled to the surface. Her attempts to catch halibut in shallow water met with no success. She returned to Woods Hole on 12 October 1886 and offloaded fish she had collected as well as the carcasses of seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

s her personnel had shot for study.

''Grampus'' made a single-day voyage to visit the mackerel

Mackerel is a common name applied to a number of different species of pelagic fish, mostly from the family Scombridae. They are found in both temperate and tropical seas, mostly living along the coast or offshore in the oceanic environment.

...

-fishing fleet in the western part of Vineyard Sound

Vineyard Sound is the stretch of the Atlantic Ocean which separates the Elizabeth Islands and the southwestern part of Cape Cod from the island of Martha's Vineyard, located offshore from the state of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), ...

off Gay Head, Massachusetts, then was engaged until March 1887 in voyages to collect spawning cod and investigate the fisheries in the Gulf of Maine, Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its northern and sout ...

, and Vineyard Sound, finding some success in bringing cod back alive in her well to Woods Hole, although over 95 percent of fish still died in the well. On 3 April 1887, she departed Woods Hole to conduct a cruise along the United States East Coast

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

from Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer months. The ...

, Massachusetts, to Cape Hatteras

Cape Hatteras is a cape located at a pronounced bend in Hatteras Island, one of the barrier islands of North Carolina.

As a temperate barrier island, the landscape has been shaped by wind, waves, and storms. There are long stretches of beach ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

.Commissioner's Report 1887, p. liv. The reasons for the behavior of mackerel during their annual spring appearance off the coasts of the United States and Canada were poorly understood when ''Grampus'' entered service,Commissioner's Report 1895, p. 80. and the cruise began a lengthy involvement for her in examining mackerel behavior as she studied schools

A school is the educational institution (and, in the case of in-person learning, the building) designed to provide learning environments for the teaching of students, usually under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of ...

of mackerel as they moved toward the coast early in the fishing season and how factors such as temperature and food sources influenced their subsequent movements. She completed this work for the season on 31 May 1887, then returned to Woods Hole on 4 June 1887.Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 495. On 3 July 1887 she sailed north to investigate reports of mackerel in the North Atlantic Ocean northeast of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

and collect birds, bird eggs, and remains of the great auk

The great auk (''Pinguinus impennis''), also known as the penguin or garefowl, is an Extinction, extinct species of flightless bird, flightless auk, alcid that first appeared around 400,000 years ago and Bird extinction, became extinct in the ...

, which had become extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

in the mid-19th century. She proceeded along the coast of Nova Scotia as far as Canso, into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence

The Gulf of St. Lawrence is a gulf that fringes the shores of the provinces of Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, in Canada, plus the islands Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, possessions of France, in ...

, north to the Magdalen Islands

The Magdalen Islands (, ) are a Canadian archipelago in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Since 2005, the 12-island archipelago is divided into two municipalities: the majority-francophone Municipality of Îles-de-la-Madeleine and the majority-angloph ...

, to St. John's, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, and then along the eastern coast of Newfoundland, finding no sign of mackerel but collecting many specimens of flora and fauna as well as a significant number of great auk bones.Commissioner's Report 1887, p. lv. She returned to Woods Hole on 1 September 1887.Commissioner's Report 1887, p. 509. She spent the winter of 1887–1888 making cruises off Massachusetts to collect brood cod.

menhaden

Menhaden, also known as mossbunker, bunker, and "the most important fish in the sea", are forage fish of the genera ''Brevoortia'' and ''Ethmidium'', two genera of marine fish in the order Clupeiformes. ''Menhaden'' is a blend of ''poghaden'' ...

reproduction in the lower Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

. Late in the 1888 fishing season, she investigated the mackerel fishery between Nantucket and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, and she collected brood cod during October and the first half of November 1888. This effort came to an end on 15 November 1888, when she ran aground during a gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface wind moving at a speed between .

on Bass RipCommissioner's Report 1888, pp. cxx-cxxi. (), a shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and Earth science, geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank (geography), bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material, and rises from the bed of a body ...

in the North Atlantic east of Nantucket Island

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined cou ...

off the coast of Massachusetts. With the weather giving signs of deteriorating further, her crew abandoned ship. Unmanned, she floated free and was adrift for several days before she was recovered and taken to Woods Hole. She underwent repairs at Gloucester.

''Grampus'' departed Woods Hole on 14 January 1889, arrived at Key West

Key West is an island in the Straits of Florida, at the southern end of the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it con ...

, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, on 27 January 1889, and began operations in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

to study the red snapper fishery on the continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

off the west coast of Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

in waters deep, continuing these operations until 27 March 1889 and battling a great deal of stormy weather to conduct her investigation. From late July through early September 1889 she conducted research in waters south of Massachusetts and Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

and between the eastern end of Nantucket Island and Block Island

Block Island is an island of the Outer Lands coastal archipelago in New England, located approximately south of mainland Rhode Island and east of Long Island's Montauk Point. The island is coterminous with the town of New Shoreham, Rhode Isl ...

, taking water temperature readings to a depth of as much as and making meteorological

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agriculture ...

observations at stations along a series of parallel lines extending as far as from the coast.Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, pp. 6–7.Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, pp. 125–126. Her work began a multiyear effort to record temperatures in vertical water columns and associated weather above those columns to discern the interaction between the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

and colder waters and the possible effect of that interaction on the behavior of various food fish

Many species of fish are caught by humans and consumed as food in virtually all regions around the world. Their meat has been an important dietary source of protein and other nutrients in the human diet.

The English language does not have a s ...

es, especially the mackerel. In September 1889 she began collecting cod eggs off Massachusetts for the Bureau of Fisheries station at Gloucester, continuing that work until the following spring.Commissioner's Report 1889–1891, p. 22.

1890s

New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

she had begun in the summer of 1889, this time joined in the effort by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey ( USC&GS; known as the Survey of the Coast from 1807 to 1836, and as the United States Coast Survey from 1836 until 1878) was the first scientific agency of the Federal government of the United State ...

survey steamer and observers stationed aboard the Nantucket South Shoals Lightship. ''Grampus'' again collected brood cod over the winter of 1890–1891. From 5 May to 18 June 1891, she again investigated the mackerel fishery off the U.S. East Coast between Massachusetts and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

, continuing the inquiry into how weather and water temperature influenced the seasonal movements of mackerel. Following that, she operated off southern New England for the third consecutive summer, from 30 June to 1 September 1891, to continue the study of vertical water columns and weather begun in 1889, this time operating only with the support of personnel embarked on the lightship

A lightvessel, or lightship, is a ship that acts as a lighthouse. It is used in waters that are too deep or otherwise unsuitable for lighthouse construction. Although some records exist of fire beacons being placed on ships in Roman times, the ...

.Commissioner's Report 1892, p. cvii.Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 33. On 5 September 1891, ''Grampus'' was on a voyage from Hyannis, Massachusetts, to Woods Hole with U.S. Commissioner of Fisheries Marshall McDonald

Marshall McDonald (October 18, 1835 – September 1, 1895) was an American engineer, geologist, mineralogist, Fish farming, pisciculturist, and Fisheries science, fisheries scientist. McDonald served as the commissioner of the United States Fish ...

and his wife and daughter, Assistant U.S. Fish Commissioner J. W. Collins (her former captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

), and two female guests aboard when she ran aground on L'Hommidieu Shoal in Vineyard Sound during a southeasterly storm. McDonald, Collins, McDonalds family members, and the other two women made it safely to Falmouth, Massachusetts, in a dory, and ''Grampus'' later was refloated and returned to service.

In late June 1892, ''Grampus'' began an assignment in the lower Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

and the waters of the North Atlantic outside its mouth to ascertain the abundance of fishes in the region; she completed this work on 20 July 1892.Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 48. Before the end of July, with Commissioner McDonald aboard, she began an investigation under his personal direction of the waters off southern New England to see if the tilefish had returned to those waters; the water-column studies of 1889 through 1891 in which she had participated demonstrated a return of warmer water to the depths the tilefish inhabited, and during several voyages in waters between Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, and Cape Henlopen, Delaware, she collected eight tilefish during the remainder of the summer, the first found there since the tremendous tilefish die-off of 1882.Commissioner's Report 1893, pp. 32–35. This finding supported a hypothesis that an influx of cold water had killed the tilefish in 1882 and that the species would reestablish itself as warmer water spread back into the area. She spent the autumn of 1892 and winter of 1892–1893 in New England waters on fish egg collection duties and in largely unsuccessful attempts to capture live cod.

In the spring of 1893, the Fish Commission tasked ''Grampus'' to evaluate the success of a five-year ban the United States Congress had passed in 1886 on the taking of mackerel prior to 1 June of each year – a prohibition which had expired after the 1892 season – by following the commercial fishing

Commercial fishing is the activity of catching fish and other seafood for Commerce, commercial Profit (economics), profit, mostly from wild fisheries. It provides a large quantity of food to many countries around the world, but those who practice ...

fleet throughout the entire 1893 spring mackerel season to see what effect the five-year ban had had on the mackerel population off the U.S. East Coast. During her cruise, she was to obtain specimens of mackerel, record physical conditions continually, and use towed nets to gather organisms that mackerel feed on.Commissioner's Report 1893, p. 47. Departing Woods Hole on 10 April 1893, she arrived at Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. The town is the administrative centre of the wider Lewes (district), district of the same name. It lies on the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse at the point where the river cuts through the Sou ...

, Delaware, on 21 April after a stormy passage and met the mackerel fleet there. The mackerel catch and weather both were poor, and by mid-May 1893 the fleet had moved north, following the mackerel in their annual migration. After calling at Woods Hole for supplies, ''Grampus'' departed on 23 May 1893 to follow the fleet to the waters off Nova Scotia. There the mackerel catch improved significantly after 1 June 1893, and ''Grampus'' returned to Woods Hole in late June 1893 with a good collection of specimens and complete set of observations. She again searched for tilefish in July and August 1893 with Commissioner McDonald aboard.

''Grampus'' again shadowed the mackerel fleet in the spring of 1894, departing Gloucester on 7 April. She was bound from Gloucester to Woods Hole before proceeding to Lewes when a serious nor'easter

A nor'easter (also northeaster; see below) is a large-scale extratropical cyclone in the western North Atlantic Ocean. The name derives from the direction of the winds that blow from the northeast. Typically, such storms originate as a low ...

struck, raising significant concerns for her safety. She survived to operate from Lewes from 20 April to 10 May, hampered as she had been a year earlier by heavy weather. She followed the fleet north to fishing grounds off the coast of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, and then across Georges Bank

Georges Bank (formerly known as St. Georges Bank) is a large elevated area of the sea floor between Cape Cod, Massachusetts (United States), and Cape Sable Island, Nova Scotia (Canada). It separates the Gulf of Maine from the Atlantic Ocean.

...

to Cape Sable Island

Cape Sable Island, locally referred to as Cape Island, is a small Canada, Canadian island at the southernmost point of the Nova Scotia peninsula. It is sometimes confused with Sable Island. Historically, the Argyle, Nova Scotia region was known ...

and Nova Scotia.Commissioner's Report 1894, p. 93. She then continued to follow schools of mackerel into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence

The Gulf of St. Lawrence is a gulf that fringes the shores of the provinces of Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, in Canada, plus the islands Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, possessions of France, in ...

as far north as Cape North on Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (, formerly '; or '; ) is a rugged and irregularly shaped island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18.7% of Nova Scotia's total area. Although ...

in Nova Scotia. Completing this work she departed for Gloucester on 13 June, arriving there on 25 June. During the last half of July and first half of August 1894, she cruised the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to examine the mackerel fishery there. After egg collection duty in the autumn of 1894 and winter of 1894–1895, she spent another spring in 1895 following mackerel schools, beginning her cruise on 12 April, operating from Lewes until 10 May, then following the mackerel to waters off New York, across Georges Bank and Browns Bank to Nova Scotia, to Cape North, and then briefly in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence before returning to Gloucester, where she arrived on 30 June 1895. From 8 August to late September 1895, she conducted the first investigation of mackerel abundance and behavior and associated environmental factors in the waters off northern New England, operating between the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy () is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its tidal range is the highest in the world.

The bay was ...

and Block Island.Commissioner's Report 1896, pp. 103–104.

''Grampus'' resumed the collection of information on the mackerel in the spring of 1896, leaving Gloucester on 11 April, arriving at Lewes on 16 April, leaving Lewes on 8 May, and working her way north along the coast of New Jersey and east along the coast of Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

and Block Island before arriving at Woods Hole on 14 May. In May and early June 1896 ''Grampus'' collected mackerel eggs in the Vineyard Sound area and off Chatham, Massachusetts, and in the latter part of June she was stationed at Small Point, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, to collect mackerel eggs in support of the Fish Commission steamer ''Fish Hawk'' at Casco Bay

Casco Bay is an bay, open bay of the Gulf of Maine on the coast of Maine in the United States. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's chart for Casco Bay marks the dividing line between the bay and the Gulf of Maine as running from ...

. The lobster

Lobsters are Malacostraca, malacostracans Decapoda, decapod crustaceans of the family (biology), family Nephropidae or its Synonym (taxonomy), synonym Homaridae. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on th ...

fishery had been in decline for a number of years, so in July ''Grampus'' moved to Rockland, Maine, to support ''Fish Hawk'', which had moved to Boothbay Harbor

Boothbay Harbor is a town in Lincoln County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,027 at the 2020 census. It includes the neighborhoods of Mount Pisgah, and Sprucewold, the Bayville and West Boothbay Harbor villages, and the Isle of Sp ...