UNESCO Statements On Race on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

UNESCO, 1952 Four scientists are listed as "frankly opposed" to the statement as a whole: C. D. Darlington,

PDF:

A draft of the statement was prepared by the Director-General and "eminent specialists in human rights". It was discussed at a meeting by government representatives from over 100 member states. It was recommended that the representatives should include among them "social scientists and other persons particularly qualified to in the social, political, economic, cultural, and scientific aspects of the problem". A number of non-governmental and inter-governmental organizations sent observers. A final text of was adopted by the meeting of government representatives "by consensus, without opposition or vote" and later by the UNESCO General Conference, Twentieth Session.

PDF:

to add to its dialogue about racial equality with recommendations for tolerant treatment of persons with varied racial and cultural backgrounds. It stated "Tolerance is respect, acceptance and appreciation of the rich diversity of our world's cultures, our forms of expression and ways of being human. It is fostered by knowledge, openness, communication, and freedom of thought, conscience and belief. Tolerance is harmony in difference. It is not only a moral duty, it is also a political and legal requirement. Tolerance, the virtue that makes peace possible, contributes to the replacement of the culture of war by a culture of peace."

The Race Question, 1950Statement on Race and Racial Prejudice, 1967

{{Authority control Scientific racism UNESCO 1950 in science Ethnicity Ethnology Historical definitions of race Race (human categorization) Politics and race 1950 in politics 1950 documents 1951 documents 1952 documents 1963 documents 1964 documents 1967 documents 1978 documents

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

has published several statements about issues of race.

The statements include:

*''Statement on race'' (Paris, July 1950)

*''Statement on the nature of race and race differences'' (Paris, June 1951)

*''Proposals on the biological aspects of race'' (Moscow, August 1964)

*''Statement on race and racial prejudice'' (Paris, September 1967)

Other statements include the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Declaration may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Declaration'' (book), a self-published electronic pamphlet by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri

* ''The Declaration'' (novel), a 2008 children's novel by Gemma Malley

Music ...

(1963), the "Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice" (1978) and the "Declaration of Principles on Tolerance" (1995).

''Statement on race'' (1950)

''Statement on race'' is the first statement on race issued by UNESCO. It was issued on 18 July 1950"The Race Question"UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, 1950, 11pp following World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

racism, to clarify what was scientifically known about race, and as a moral condemnation of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

.

It was drafted by Ernest Beaglehole

Ernest Beaglehole (25 August 1906 – 23 October 1965) was a New Zealand psychologist and ethnologist best known for his work in establishing an anthropological baseline for numerous Pacific Island cultures.

Early life and education

Beaglehole ...

, psychologist and ethnologist; Juan Comas

Juan Comas Camps (January 23, 1900 in Alayor, Menorca, Spain – January 18, 1979 in Mexico City, Mexico) was a Spanish-Mexican anthropologist, notable for his critical work on race, and his participation in drafting the UNESCO statement on ra ...

, anthropologist; Luiz de Aguiar Costa Pinto, sociologist; Franklin Frazier, sociologist specialised in race relations studies; Morris Ginsberg

Morris Ginsberg (14 May 1889 – 31 August 1970) was a British sociologist, who played a key role in the development of the discipline. He served as editor of ''The Sociological Review'' in the 1930s and later became the founding chairman of ...

, founding chairperson of the British Sociological Association

The British Sociological Association (BSA) is a scholarly and professional society for sociologists in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1951, the BSA is the national subject association for sociology in the UK. It publishes the academic journals ' ...

; Humayun Kabir, writer, philosopher, and twice Education Minister of India; Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss ( ; ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a Belgian-born French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair o ...

, one of the founders of ethnology

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).

Sci ...

and leading theorist of structural anthropology

Structural anthropology is a school of sociocultural anthropology based on Claude Lévi-Strauss' 1949 idea that immutable deep structures exist in all cultures, and consequently, that all cultural practices have homologous counterparts in other ...

; and Ashley Montagu

Montague Francis Ashley-Montagu (born Israel Ehrenberg; June 28, 1905November 26, 1999) was a British-American anthropologist who popularized the study of topics such as race and gender and their relation to politics and development. He was the ...

, anthropologist and author of '' The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity'', who was the rapporteur

A rapporteur is a person who is appointed by an organization to report on the proceedings of its meetings. The term is a French-derived word.

For example, Dick Marty was appointed ''rapporteur'' by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Eur ...

.

The statement was criticized on several grounds, in particular by natural scientists. Criticisms were submitted by Hadley Cantril

Albert Hadley Cantril, Jr. (16 June 1906 – 28 May 1969) was an American psychologist from Princeton University, who expanded the scope of the field.

Cantril made "major contributions in psychology of propaganda; public opinion research; applica ...

; Edwin Conklin

Edwin Grant Conklin (November 24, 1863 – November 20, 1952) was an American biologist and zoologist.

Life

He was born in Waldo, Ohio, the son of A. V. Conklin and Maria Hull.

He was educated at Ohio Wesleyan University and Johns Hopkins U ...

; Gunnar Dahlberg; Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Grigorievich Dobzhansky (; ; January 25, 1900 – December 18, 1975) was a Russian-born American geneticist and evolutionary biologist. He was a central figure in the field of evolutionary biology for his work in shaping the modern ...

, author of ''Genetics and the Origin of Species

''Genetics and the Origin of Species'' is a 1937 book by the Ukrainian-American evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky. It is regarded as one of the most important works of Modern synthesis (20th century), modern synthesis and was one of the ...

'' (1937); L. C. Dunn; Donald J. Hager, professor of anthropology and sociology at the University of Princeton

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

; Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist and Internationalism (politics), internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentiet ...

, first director of UNESCO and one of the many key contributors to modern evolutionary synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and s ...

; Otto Klineberg; Wilbert Moore; H. J. Muller; Gunnar Myrdal

Karl Gunnar Myrdal ( ; ; 6 December 1898 – 17 May 1987) was a Swedish economist and sociologist. In 1974, he received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences along with Friedrich Hayek for "their pioneering work in the theory of money an ...

, author of '' An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy'' (1944); Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, initia ...

, a biochemist specialist of Chinese science; and geneticist Curt Stern

Curt Stern (August 30, 1902 – October 23, 1981) was a German-born American geneticist.

Life

Curt Jacob Stern was born into a middle-class Jewish family in Hamburg, Germany on August 30, 1902. He was the first son of Earned S. Stern, born ...

. The text was then revised by Ashley Montagu and the revised statement was published in 1951, as well as a book detailing the criticisms in 1952.

UNESCO would start a campaign to spread the results of the report to a "vast public" such as by publishing pamphlets. It described Brazil as having an "exemplary situation" regarding race relations and that research should be undertaken in order to understand the causes of this "harmony".

Contents

The introduction states that it was inevitable that UNESCO should take a position in the controversy. The preamble to the UNESCO constitution states that it should combat racism. The constitution itself stated that "The great and terrible war that has now ended was a war made possible by the denial of the democratic principles of thedignity

Dignity is a human's contentment attained by satisfying physiological needs and a need in development. The content of contemporary dignity is derived in the new natural law theory as a distinct human good.

As an extension of the Enlightenment- ...

, equality

Equality generally refers to the fact of being equal, of having the same value.

In specific contexts, equality may refer to:

Society

* Egalitarianism, a trend of thought that favors equality for all people

** Political egalitarianism, in which ...

and mutual respect

Respect, also called esteem, is a positive feeling or deferential action shown towards someone or something considered important or held in high esteem or regard. It conveys a sense of admiration for good or valuable qualities. It is also th ...

of men, and by the propagation, in their place, through ignorance and prejudice

Prejudice can be an affect (psychology), affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived In-group and out-group, social group membership. The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavourable) evaluation or classifi ...

, of the doctrine of the ''inequality'' of men and races."

A 1948 UN Social and Economic Council resolution called upon UNESCO to consider the timeliness "of proposing and recommending the general adoption of a programme of dissemination of scientific facts designed to bring about the disappearance of that which is commonly called race prejudice." In 1949, the General Conference of UNESCO adopted three resolutions which committed it to "study and collect scientific materials concerning questions of race", "to give wide diffusion to the scientific material collected", and "to prepare an education campaign based on this information."

Furthermore, in doing this

The introduction stated "Knowledge of the truth does not always help change emotional attitudes that draw their real strength from the subconscious or from factors beside the real issue." But it could "however, prevent rationalizations of reprehensive acts or behaviour prompted by feelings that men will not easily avow openly."

UNESCO made a moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

statement:

The statement argued that there was no evidence for intellectual or personality differences.

The statement did not reject the idea of a biological basis to racial categories. It defined the concept of race in terms of a population defined by certain anatomical and physiological characteristics diverging from other populations; it gives as examples the Caucasian

Caucasian may refer to:

Common meanings

*Anything from the Caucasus region or related to it

** Ethnic groups in the Caucasus

** ''Caucasian Exarchate'' (1917–1920), an ecclesiastical exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Caucasus re ...

, Mongoloid

Mongoloid () is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms ...

, and Negroid races. However, the statement argued that "National, religious, geographic, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups: and the cultural traits of such groups have no demonstrated genetic connection with racial traits. Because serious errors of this kind are habitually committed when the term 'race' is used in popular parlance, it would be better when speaking of human races to drop the term 'race' altogether and speak of ethnic groups."

''Statement on the nature of race and race differences'' (1951)

Despite the introduction to the 1950 statement declaring "The competence and objectivity of the scientists who signed the document in its final form cannot be questioned", the first version of the statement was heavily criticized. L.C. Dunn, the rapporteur for the 1951 statement, explained the controversy as "At the first discussion on the problem of race, it was chiefly sociologists who gave their opinions and framed the 'Statement on Race'. That statement had a good effect, but it did not carry the authority of just those groups within whose special province fall the biological problems of race, namely the physical anthropologists and geneticists. Secondly, the first statement did not, in all its details, carry conviction of these groups and, because of this, it was not supported by many authorities in these two fields. In general, the chief conclusions of the first statement were sustained, but with differences in emphasis and with some important omissions." The 1951 statement declared that ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

'' is one species.

The authors of the 1951 statement "agreed to reserve race as the word to be used" for "groups of mankind possessing well-developed and primarily heritable physical differences from other groups."

"The concept of race is unanimously regarded by anthropologists as a classificatory device providing a zoological frame within which the various groups of mankind may be arranged and by means of which studies of evolutionary processes can be facilitated. In its anthropological sense, the word 'race' should be reserved for groups of mankind possessing well-developed and primarily heritable physical differences from other groups." These differences have been caused in part by partial isolation preventing intermingling, geography an important explanation for the major races, often cultural for the minor races. National, religious, geographical, linguistic and cultural groups do not necessarily coincide with racial groups.

The statement declared "There is no evidence for the existence of so-called 'pure races'" and "no biological justification for prohibiting inter- marriage between persons of different races."

''The Race Concept'' (1952)

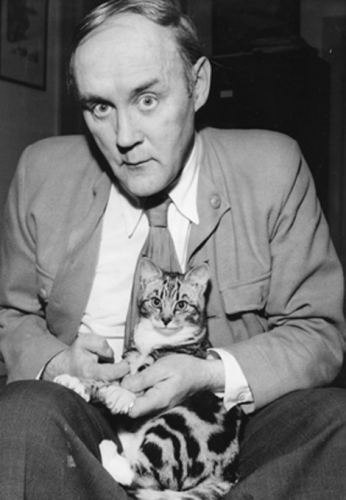

In 1952, UNESCO published a follow-up book, ''The Race Concept: Results of an Inquiry'', containing the 1951 statement, followed by comments and criticisms from many of the scientists engaged in the drafting and review of the text."The Race Concept: Results of an Inquiry"UNESCO, 1952 Four scientists are listed as "frankly opposed" to the statement as a whole: C. D. Darlington,

Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

, Giuseppe E. Genna

Giuseppe is the Italian form of the given name Joseph,

from Latin Iōsēphus from Ancient Greek Ἰωσήφ (Iōsḗph), from Hebrew יוסף.

The feminine form of the name is Giuseppa or Giuseppina.

People with the given name include:

:''Note ...

of the University of Florence

The University of Florence ( Italian: ''Università degli Studi di Firenze'') (in acronym UNIFI) is an Italian public research university located in Florence, Italy. It comprises 12 schools and has around 50,000 students enrolled.

History

The f ...

, and Carleton S. Coon

Carleton Stevens Coon (June 23, 1904 – June 3, 1981) was an American anthropologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He is best known for his scientific racist theories concerning the parallel evolution of human races, which ...

. Among these, English statistician

A statistician is a person who works with Theory, theoretical or applied statistics. The profession exists in both the private sector, private and public sectors.

It is common to combine statistical knowledge with expertise in other subjects, a ...

and biologist Fisher insisted on racial differences, arguing that evidence and everyday experience showed that human groups differ profoundly "in their innate capacity for intellectual and emotional development" and concluded that the "practical international problem is that of learning to share the resources of this planet amicably with persons of materially different nature", and that "this problem is being obscured by entirely well-intentioned efforts to minimize the real differences that exist."

The book stated that "When intelligence tests, even non-verbal, are made on a group of non-literate people, their scores are usually lower than those of more civilised people" but concluded that "Available scientific knowledge provides no basis for believing that the groups of mankind differ in their innate capacity for intellectual and emotional development."

''Statement on race and racial prejudice'' (1967)

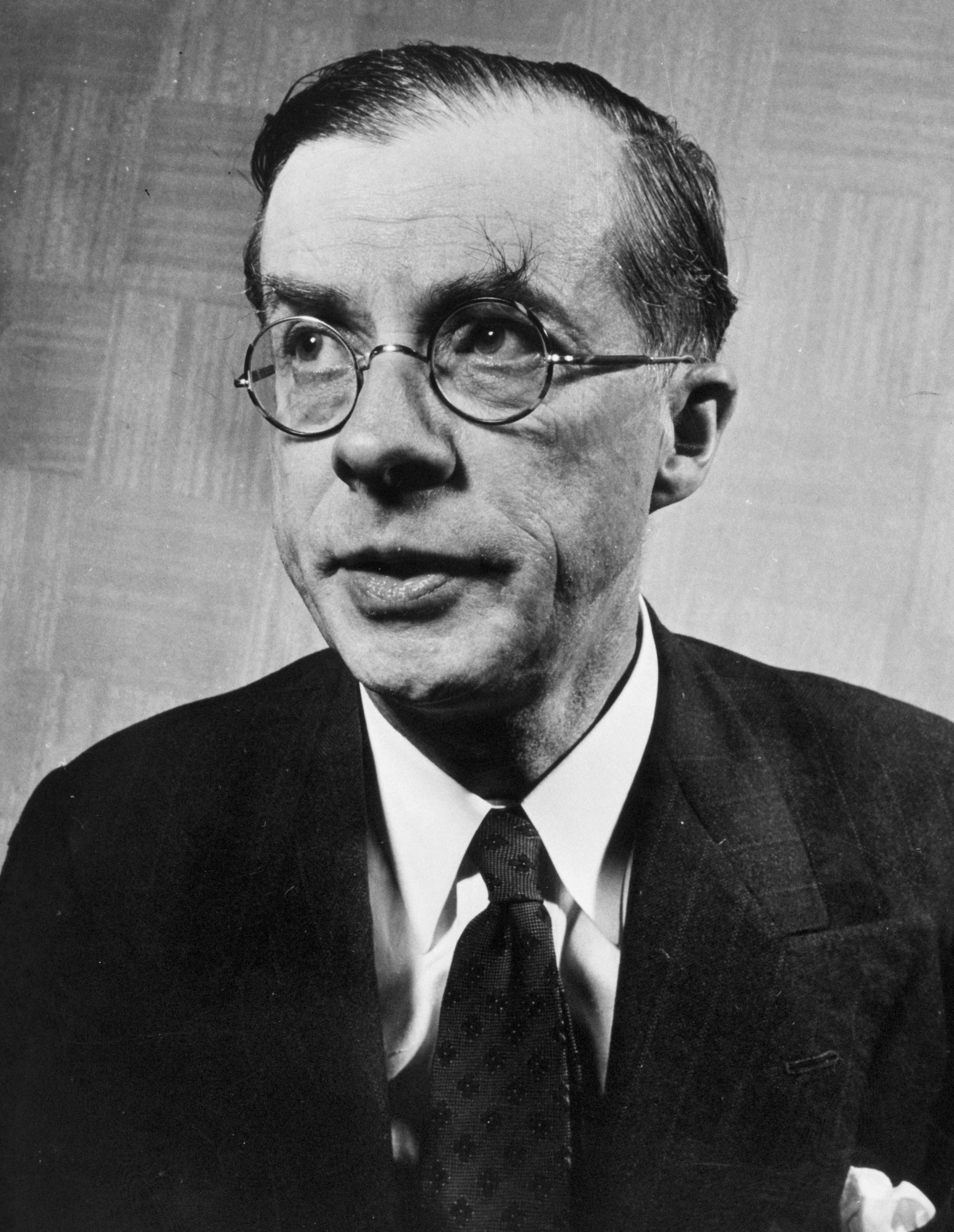

According toMichael Banton

Michael Parker Banton CMG, FRAI (8 September 1926 – 22 May 2018) was a British social scientist, known primarily for his publications on racial and ethnic relations. He was also the first editor of ''Sociology'' (1966-1969).

Education

B ...

, "The 1950 statement appeared to assume that once the erroneous nature of racist doctrines had been exposed, the structure of racial prejudice and discrimination would collapse. The eminent scholars who composed the document did not consider explicitly the other sources of racial hostility." Therefore, in 1967 a fourth panel of experts was assembled for one week to discuss social, ethical and philosophical aspects of race.

''Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice'' (1978)

In 1978, the ''Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice'' was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO, a political body consisting of representatives of member states. This declaration stated that "All peoples of the world possess equal faculties for attaining the highest level in intellectual, technical, social, economic, cultural and political development" and "The differences between the achievements of the different peoples are entirely attributable to geographical, historical, political, economic, social and cultural factors." It also argued for implementing a number of policies in order to combat racism and inequalities, and stated that "Population groups of foreign origin, particularly migrant workers and their families who contribute to the development of the host country, should benefit from appropriate measures designed to afford them security and respect for their dignity and cultural values and to facilitate their adaptation to the host environment and their professional advancement with a view to their subsequent reintegration in their country of origin and their contribution to its development; steps should be taken to make it possible for their children to be taught their mother tongue.""Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice"UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, 1978.PDF:

A draft of the statement was prepared by the Director-General and "eminent specialists in human rights". It was discussed at a meeting by government representatives from over 100 member states. It was recommended that the representatives should include among them "social scientists and other persons particularly qualified to in the social, political, economic, cultural, and scientific aspects of the problem". A number of non-governmental and inter-governmental organizations sent observers. A final text of was adopted by the meeting of government representatives "by consensus, without opposition or vote" and later by the UNESCO General Conference, Twentieth Session.

''Declaration of Principles on Tolerance'' (1995)

In 1995, UNESCO published a ''Declaration of Principles on Tolerance''UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, 1995.PDF:

to add to its dialogue about racial equality with recommendations for tolerant treatment of persons with varied racial and cultural backgrounds. It stated "Tolerance is respect, acceptance and appreciation of the rich diversity of our world's cultures, our forms of expression and ways of being human. It is fostered by knowledge, openness, communication, and freedom of thought, conscience and belief. Tolerance is harmony in difference. It is not only a moral duty, it is also a political and legal requirement. Tolerance, the virtue that makes peace possible, contributes to the replacement of the culture of war by a culture of peace."

Legacy

The 1950 UNESCO statement contributed to the 1954 U.S. Supreme Courtdesegregation

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation), leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity regardless of race, and the development of a culture that draws ...

decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka''.

See also

*Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions

The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions is an international treaty adopted in October 2005 in Paris during the 33rd session of the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific a ...

*International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is a United Nations convention. A third-generation human rights instrument, the Convention commits its members to the elimination of racial discri ...

*International Day for Tolerance

The International Day for Tolerance is an annual observance day declared by UNESCO in 1995 to generate public awareness of the dangers of intolerance. It is observed on 16 November.

Conferences and festivals

Every year various conferences and ...

*Nazism and race

The German Nazi Party adopted and developed several racial hierarchical categorizations as an important part of its racist ideology (Nazism) in order to justify enslavement, extermination, ethnic persecution and other atrocities against ...

*Racial Equality Proposal

The Racial Equality Proposal was an amendment to the Treaty of Versailles that was considered at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Proposed by Japan, it was never intended to have any universal implications, but one was attached to it anyway, whic ...

* World Conference against Racism

References

External links

The Race Question, 1950

{{Authority control Scientific racism UNESCO 1950 in science Ethnicity Ethnology Historical definitions of race Race (human categorization) Politics and race 1950 in politics 1950 documents 1951 documents 1952 documents 1963 documents 1964 documents 1967 documents 1978 documents