U.S. imperialism or American imperialism is the expansion of political, economic, cultural, media, and military influence beyond the boundaries of the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conquest; military protection;

gunboat diplomacy

Gunboat diplomacy is the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to the superior force.

The term originated in ...

;

unequal treaties

The unequal treaties were a series of agreements made between Asian countries—most notably Qing China, Tokugawa Japan and Joseon Korea—and Western countries—most notably the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, the Unit ...

; subsidization of preferred factions;

regime change

Regime change is the partly forcible or coercive replacement of one government regime with another. Regime change may replace all or part of the state's most critical leadership system, administrative apparatus, or bureaucracy. Regime change may ...

; economic or diplomatic support; or economic penetration through private companies, potentially followed by

diplomatic or forceful intervention when those interests are threatened.

The policies perpetuating American imperialism and expansionism are usually considered to have begun with "

New Imperialism

In History, historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of Colonialism, colonial expansion by European powers, the American imperialism, United States, and Empire of Japan, Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

" in the late 19th century, though some consider

American territorial expansion and

settler colonialism

Settler colonialism is a logic and structure of displacement by Settler, settlers, using colonial rule, over an environment for replacing it and its indigenous peoples with settlements and the society of the settlers.

Settler colonialism is ...

at the expense of

Indigenous Americans to be similar enough in nature to be identified with the same term. While the United States has never officially identified itself and its territorial possessions as an empire, some commentators have referred to the country as such, including

Max Boot

Max A. Boot (born September 12, 1969) is a Russian-born naturalized American author, editorialist, lecturer, and military historian. He worked as a writer and editor for ''The Christian Science Monitor'' and then for ''The Wall Street Journal ...

,

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. ( ; born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 – February 28, 2007) was an American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of the influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. and a ...

, and

. Other commentators have accused the United States of practicing

neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

—sometimes defined as a modern form of

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of ...

—which leverages economic power rather than military force in an

informal empire

The term ''informal empire'' describes the spheres of influence which a polity may develop that translate into a degree of influence over a region or country, which is not a formal colony, protectorate, Tributary state, tributary or vassal sta ...

; the term "neocolonialism" has occasionally been used as a contemporary synonym for

modern-day imperialism.

The question of whether the United States should intervene in the affairs of foreign countries has been a much-debated topic in domestic politics for the country's entire history.

Opponents of interventionism have pointed to the country's origin as

a former colony that rebelled against an overseas king, as well as the American values of democracy, freedom, and independence.

Conversely, supporters of interventionism and of American presidents who have attacked foreign countries — most notably

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

,

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

,

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

,

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

,

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, and

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

— have justified their interventions in (or whole seizures of) various countries by citing the necessity of advancing American economic interests, such as trade and debt management; preventing European intervention (colonial or otherwise) in the

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

, manifested in the anti-European

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

of 1823; and the benefits of keeping "good order" around the world.

History

Overview

Despite periods of peaceful co-existence in the early 1600s,

wars with Native Americans resulted in substantial territorial gains for American colonists who were expanding into native land. Wars with the Native Americans continued intermittently

after independence, and an

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

campaign known as

Indian removal gained for

European American

European Americans are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes both people who descend from the first European settlers in the area of the present-day United States and people who descend from more recent European arrivals. Since th ...

settler

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a Human settlement, settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among ...

s more valuable territory on the eastern side of the continent.

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, a founding father and first president of the United States, began a policy of

United States non-interventionism

United States non-interventionism primarily refers to the Foreign policy of the United States, foreign policy that was eventually applied by the United States between the late 18th century and the first half of the 20th century whereby it sought t ...

which lasted into the 1800s. The United States promulgated the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

in 1823, in order to stop further European colonialism in the Latin America. Desire for territorial expansion to the Pacific Ocean was explicit in the idea of

manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

. The giant

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

was peaceful, but the

annexation of of Mexican territory was the result of the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

of 1846.

The

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

reoriented American foreign policy towards opposing communism, and prevailing U.S. foreign policy embraced its role as a nuclear-armed global superpower. Through the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

and

Reagan Doctrine

The Reagan Doctrine was a United States foreign policy strategy implemented by the administration of President Ronald Reagan to overwhelm the global influence of the Soviet Union in the late Cold War. As stated by Reagan in his State of the Unio ...

the United States framed the mission as protecting free peoples against an undemocratic system, anti-Soviet foreign policy became coercive and occasionally covert.

United States involvement in regime change

Since the 19th century, the United States government has participated and interfered, both overtly and covertly, in the replacement of many foreign governments. In the latter half of the 19th century, the U.S. government initiated actions for ...

included

overthrowing the democratically elected government of Iran, the

Bay of Pigs invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called or after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in April 1961 by the United States of America and the Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front ...

in Cuba, occupation of

Grenada

Grenada is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The southernmost of the Windward Islands, Grenada is directly south of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and about north of Trinidad and Tobago, Trinidad and the So ...

, and interference in various foreign elections. The long and bloody

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

led to widespread criticism of an "

arrogance of power" and

violations of international law emerging from an "

imperial presidency," with

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

, among others, accusing the US of a

new form of colonialism.

In terms of territorial acquisition, the United States has integrated (with voting rights) all of its acquisitions on the North American continent, including the non-contiguous

Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

. Hawaii has also become a state with equal representation to the mainland, but other island jurisdictions acquired during wartime remain territories, namely

Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

,

Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

, the

United States Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands, officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and a territory of the United States. The islands are geographically part of the Virgin Islands archipelago and are located ...

,

American Samoa

American Samoa is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States located in the Polynesia region of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. Centered on , it is southeast of the island count ...

, and the

Northern Mariana Islands

The Northern Mariana Islands, officially the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territory and Commonwealth (U.S. insular area), commonwealth of the United States consistin ...

. (The federal government officially

apologized for the overthrow of the Hawaiian government in 1993.) The remainder of acquired territories have become independent with varying degrees of cooperation, ranging from three

freely associated states

The Compacts of Free Association (COFA) are international agreements establishing and governing the relationships of free association between the United States and the three Pacific Island sovereign states of the Federated States of Micronesia (F ...

which participate in federal government programs in exchange for military basing rights, to Cuba which severed diplomatic relations during the Cold War. The United States was a public advocate for European

decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

after World War II (having started a ten-year independence transition for the Philippines in 1934 with the

Tydings–McDuffie Act

The Philippine Independence Act, or Tydings–McDuffie Act (), is an Act of Congress that established the process for the Philippines, then a US territory, to become an independent country after a ten-year transition period. Under the act, th ...

). Even so, the US desire for an informal system of global

primacy in an "

American Century

The American Century is a characterization of the period since the middle of the 20th century as being largely dominated by the United States in political, economic, technological, and cultural terms. It is comparable to the description of the p ...

" often brought them into conflict with

national liberation movements

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ...

. The United States has now

granted citizenship to Native Americans and recognizes some degree of

tribal sovereignty

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

.

1700s–1800s: Indigenous American Wars and manifest destiny

Yale historian

Paul Kennedy

Paul Michael Kennedy (born 17 June 1945) is a British historian specialising in the history of international relations, economic power and grand strategy. He is on the editorial board of numerous scholarly journals and writes for ''The New Y ...

has asserted, "From the time the first settlers arrived in

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

from

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and started moving westward, this was an imperial nation, a conquering nation."

[Emily Eakin "Ideas and Trends: All Roads Lead To DC" New York Times, March 31, 2002.] Expanding on George Washington's description of the early United States as an "infant empire", Benjamin Franklin wrote: "Hence the Prince that acquires new Territory, if he finds it vacant, or removes the Natives to give his own People Room; the Legislator that makes effectual Laws for promoting of Trade, increasing Employment, improving Land by more or better Tillage; providing more Food by Fisheries; securing Property, etc. and the Man that invents new Trades, Arts or Manufactures, or new Improvements in Husbandry, may be properly called Fathers of their Nation, as they are the Cause of the Generation of Multitudes, by the Encouragement they afford to Marriage." Thomas Jefferson asserted in 1786 that the United States "must be viewed as the nest from which all America, North & South is to be peopled.

..The navigation of the Mississippi we must have. This is all we are as yet ready to receive.". From the left

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

writes that "the United States is the one country that exists, as far as I know, and ever has, that was founded as an empire explicitly".

A national drive for territorial acquisition across the continent was popularized in the 19th century as the ideology of manifest destiny. The policy of settlement of land was a foundational goal of the United States of America, with one of the driving factors of discontent with British rule originating from the

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by British King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The ...

, which barred settlement west of the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

. As part of the desire of Manifest Destiny to open up land for American settlement came campaigns in the Great Lakes region which saw the United States fight the

Northwestern Confederacy

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to it ...

resulting in the

Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1785–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native Americans in the United States, Native American na ...

. Subsequent treaties such as the

Treaty of Greenville

The Treaty of Greenville, also known to Americans as the Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., but formally titled ''A treaty of peace between the United States of America, and the tribes of Indians called the Wyandots, Delawares, Shawanees, Ottawas ...

and the

Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809)

The Treaty of Fort Wayne, sometimes called the Ten O'clock Line Treaty or the Twelve Mile Line Treaty, is an 1809 treaty that obtained 29,719,530 acres of Native American land for the settlers of Illinois and Indiana. The negotiations primarily ...

resulted in a rise of Anti-American sentiment among the Native Americans in the Great Lakes region, which helped to create

Tecumseh's Confederacy which was defeated by the end of the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. The

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

of 1830 culminated in the deportation of 60,000 Native Americans in an event known as the

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of about 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their black slaves within that were ethnically cleansed by the U ...

, where up to 16,700 people died in an act of

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

. The deportation of Natives West of the Mississippi, resulted in significant economic gains for settlers. For example, the

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

firm, Byrd and Belding earned up to $27,000 in two years through supplying food. The policy of Manifest Destiny would continue to be realized with the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

of 1846, which resulted in the

cession of of Mexican territory to the United States, stretching up to the Pacific coast.

The

Whig Party strongly opposed this war and expansionism generally.

Following the American victory over Mexico, colonization and settlement of California would begin which would soon lead to the

California genocide

The California genocide was a series of genocidal massacres of the indigenous peoples of California by United States soldiers and settlers during the 19th century. It began following the American conquest of California in the Mexican–Americ ...

. Estimates of total deaths in the genocide vary greatly from 2,000 to 100,000. The discovery of Gold in California resulted in an influx of settlers, who formed militias to kill and displace Indigenous peoples. The government of California supported expansion and settlement through the passage of the

Act for the Government and Protection of Indians

The Act for the Government and Protection of Indians (Chapter 133, California Statutes, Cal. Stats., April 22, 1850), nicknamed the Indian Indenture Act was enacted by the first session of the California State Legislature and signed into law by ...

which legalized the enslavement of Native Americans and allowed settlers to capture and force them into labor.

California further offered and paid bounties for the killing of Native Americans.

American expansion in the Great Plains resulted in conflict between many tribes West of the Mississippi and the United States. In 1851, the

Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed, which gave the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes territory from the North Platte River in present-day Wyoming and Nebraska southward to the Arkansas River in present-day Colorado and Kansas. The land was initially not wanted by White settlers, but following the discovery of gold in the region, settlers began to pour into the territory. In 1861, six chiefs of the Southern Cheyenne and four of the Arapaho signed the

Treaty of Fort Wise

The Treaty of Fort Wise of 1861 was a treaty entered into between the United States and six chiefs of the Southern Cheyenne and four of the Southern Arapaho Indian tribes. A significant proportion of Cheyennes opposed this treaty on the grounds ...

which saw the loss of 90% of their land.

[Greene, 2004, p. 27] The refusal of various warriors to recognise the treaty resulted in white settlers starting to believe that war was coming. The subsequent

Colorado War

The Colorado War was an Indian War fought in 1864 and 1865 between the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and allied Brulé and Oglala Lakota (or Sioux) peoples versus the U.S. Army, Colorado militia, and white settlers in Colorado Territory and ...

would result in the

Sand Creek Massacre

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by the U.S. Army in the American Indian Genocide that occurred on No ...

in which up to 600 Cheyenne were killed, most of whom were children and women. On October 14, 1865, the chiefs of what remained of the Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos agreed to live south of the Arkansas, sharing land that belonged to the Kiowas, and thereby relinquish all claims in the Colorado territory.

Following the victory of

Red Cloud

Red Cloud (; – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1865 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western territories. He led the Lakota to victory over ...

in

Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War or the Powder River War) was an armed conflict between an alliance of the Lakota people, Lakota, Cheyenne, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho peoples against the United States and the Crow ...

over the United States, the

Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)

The Treaty of Fort Laramie (also the Sioux Treaty of 1868) is an agreement between the United States and the Oglala Lakota, Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and Arapaho Nation, following the failure of ...

was signed. This treaty led to the creation of the

Great Sioux Reservation

The Great Sioux Reservation was an Indian reservation created by the United States through treaty with the Sioux, principally the Lakota, who dominated the territory before its establishment. In the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the reservation ...

. However, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills resulted in a surge of White settlement in the region. The gold rush was very profitable for the White settlers and the American government, with just one of the Black Hill Mines yielding $500 Million in gold. Attempts to purchase the land failed, and the

Great Sioux War

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota people, Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of t ...

began as a result. Despite initial success by Native Americans in the war's first few battles, most notably the

Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota people, Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Si ...

, the United States eventually won and ended the reservation, carving it up into smaller reservations. The reservation system did not just serve as a way to facilitate American settlement and expansion of land, but also enriched local merchants and businesses who held significant economic power over the Native tribes. Traders would often accept payment for goods via annuity money from land sales contributing to further poverty.

In the South-West, various settlements and communities had been established thanks to profits from the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. In order to maintain revenue and profit, settlers often waged war against native tribes. By 1871, the settlement of

Tucson

Tucson (; ; ) is a city in Pima County, Arizona, United States, and its county seat. It is the second-most populous city in Arizona, behind Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix, with a population of 542,630 in the 2020 United States census. The Tucson ...

for example had a population of three thousand, including saloon-keepers, traders and contractors who had made fortunes during the Civil War and were hopeful of continuing their profits with an Indian war. Desire to fight resulted in the

Camp Grant Massacre

The Camp Grant massacre, on April 30, 1871, was an attack on Pinal and Aravaipa Apaches who surrendered to the United States Army at Camp Grant, Arizona, along the San Pedro River. The massacre led to a series of battles and campaigns fought ...

of 1871 where up to 144

Apache

The Apache ( ) are several Southern Athabaskan language-speaking peoples of the Southwestern United States, Southwest, the Southern Plains and Northern Mexico. They are linguistically related to the Navajo. They migrated from the Athabascan ho ...

were killed, most being women and children. Up to 27 Apache children were captured and sold into slavery in

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

. In the 1860s, the

Navajo

The Navajo or Diné are an Indigenous people of the Southwestern United States. Their traditional language is Diné bizaad, a Southern Athabascan language.

The states with the largest Diné populations are Arizona (140,263) and New Mexico (1 ...

faced deportation in an attempted act of

ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

under the

Long Walk of the Navajo

The Long Walk of the Navajo, also called the Long Walk to Bosque Redondo (), was the deportation and ethnic cleansing of the Navajo people by the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government and the United States A ...

. The "Long Walk" started at the beginning of spring 1864. Bands of Navajo led by the Army were relocated from their traditional lands in eastern Arizona Territory and western New Mexico Territory to Fort Sumner. Around 200 died during the march. During the march, New Mexican slavers, assisted by the Ute often attacked isolated bands, killing the men, taking the women and children captive, and capturing horses and livestock. As part of these raids, a large number of slaves were taken and sold throughout the region.

Starting in 1820, the

American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn peop ...

began subsidizing free black people to colonize the west coast of Africa. In 1822, it declared the colony of

Liberia

Liberia, officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast–Lib ...

, which became independent in 1847. By 1857, Liberia had merged with other colonies formed by state societies, including the

Republic of Maryland

The Republic of Maryland (also known variously as the Independent State of Maryland, Maryland-in-Africa, and Maryland in Liberia) was a country in West Africa that existed from 1834 to 1857, when it was merged into what is now Liberia. The area ...

,

Mississippi-in-Africa, and

Kentucky in Africa

Kentucky in Africa was a colony in present-day Montserrado County, Liberia, founded in 1828 and settled by American free people of color, many of them former slaves. A state affiliate of the American Colonization Society, the Kentucky State Colo ...

.

President James Monroe presented his famous

doctrine for the western hemisphere in 1823. Historians have observed that while the Monroe Doctrine contained a commitment to resist colonialism from Europe, it had some aggressive implications for American policy, since there were no limitations on the US's actions mentioned within it. Historian Jay Sexton notes that the tactics used to implement the doctrine were modeled after those employed by European imperial powers during the 17th and 18th centuries. From the left historian

William Appleman Williams

William Appleman Williams (June 12, 1921 – March 5, 1990) was one of the 20th century's most prominent revisionist historians of American diplomacy. He achieved the height of his influence while on the faculty of the department of history at t ...

described it as "imperial anti-colonialism."

In the older historiography

William Walker's filibustering represented the high tide of antebellum American imperialism. His brief seizure of Nicaragua in 1855 is typically called a representative expression of

Manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

with the added factor of trying to expand slavery into Central America. Walker failed in all his escapades and never had official U.S. backing. Historian Michel Gobat, however, presents a strongly revisionist interpretation. He argues that Walker was invited in by Nicaraguan liberals who were trying to force economic modernization and political liberalism. Walker's government comprised those liberals, as well as Yankee colonizers, and European radicals. Walker even included some local Catholics as well as indigenous peoples, Cuban revolutionaries, and local peasants. His coalition was much too complex and diverse to survive long, but it was not the attempted projection of American power, concludes Gobat.

The

Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonial empires, the United States, and briefly the Confederate States of America and Republic of Texas agains ...

against the

indigenous peoples of the Americas

In the Americas, Indigenous peoples comprise the two continents' pre-Columbian inhabitants, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with them in the 15th century, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with the pre-Columbian population of ...

began in the

colonial era Colonial period (a period in a country's history where it was subject to management by a colonial power) may refer to:

Continents

*European colonization of the Americas

* Colonisation of Africa

* Western imperialism in Asia

Countries

* Col ...

. Their escalation under the federal republic allowed the US to dominate North America and carve out the 48

contiguous states. This can be considered to be an explicitly colonial process in light of arguments that Native American nations were sovereign entities prior to annexation. Their sovereignty was systematically undermined by US state policy (usually involving unequal or

broken treaties) and

white settler-colonialism. Furthermore, following the Dawes Act of 1887 native american systems of land tenure and communal ownership were ended, in favour of private property and

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

.

This resulted in the loss of around 100 Million acres of land from 1887 to 1934.

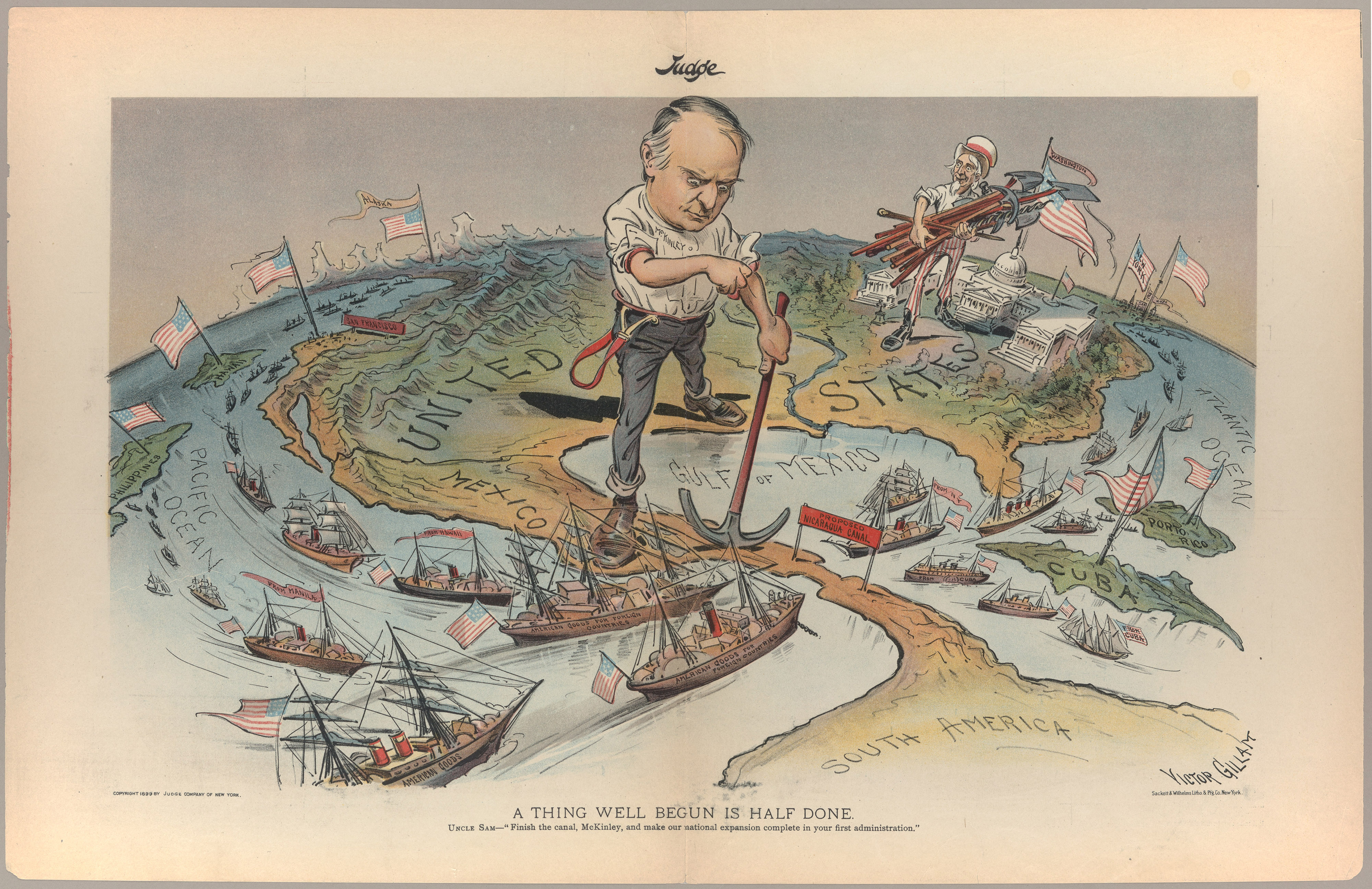

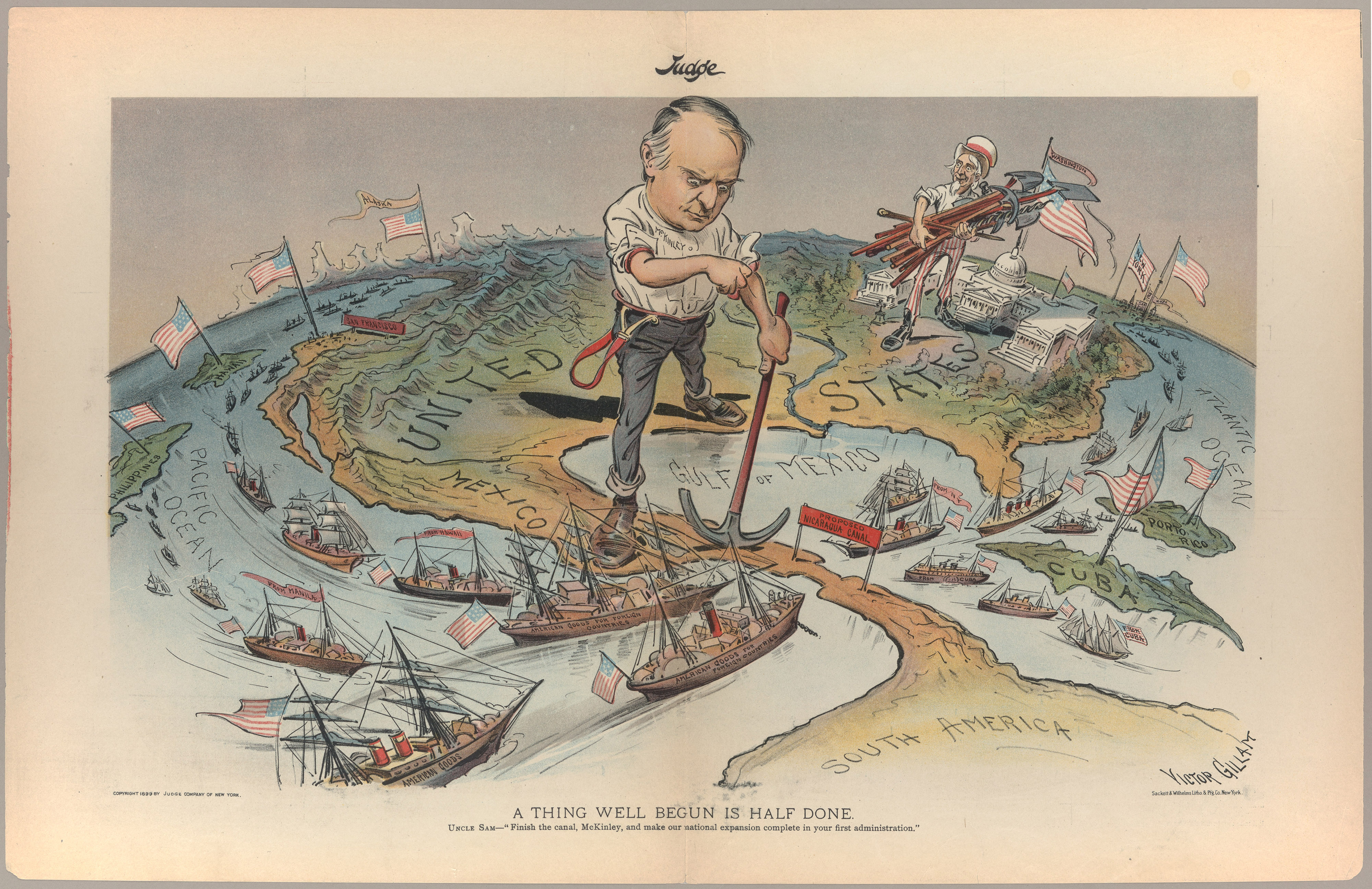

1890s–1900s: New Imperialism and "The White Man's Burden"

A variety of factors converged during the "

New Imperialism

In History, historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of Colonialism, colonial expansion by European powers, the American imperialism, United States, and Empire of Japan, Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

" of the late 19th century, when the United States and the other

great powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

rapidly expanded their overseas territorial possessions. One of these factors was the prevalence of overt racism, notably

John Fiske's conception of "

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

" racial superiority and

Josiah Strong

Josiah Strong (April 14, 1847 – June 26, 1916) was an American Protestant clergyman, organizer, editor, and author. He was a leader of the Social Gospel movement, calling for social justice and combating social evils. He supported missionary wor ...

's call to "civilize and Christianize." The concepts were manifestations of a growing

Social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

and racism in some schools of American political thought.

Early in his career, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy,

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

was instrumental in preparing the Navy for the

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

and was an enthusiastic proponent of testing the U.S. military in battle, at one point stating "I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one."

Roosevelt claimed that he rejected imperialism, but he embraced the near-identical doctrine of

expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

. When

Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

wrote the imperialist poem "

The White Man's Burden

"The White Man's Burden" (1899), by Rudyard Kipling, is a poem about the Philippine–American War (1899–1902) that exhorts the United States to assume colonial control of the Filipino people and their country.''

In "The White Man's Burden ...

" for Roosevelt, the politician told colleagues that it was "rather poor poetry, but good sense from the expansion point of view." Roosevelt proclaimed his own

corollary to the Monroe Doctrine as justification, although his ambitions extended even further, into the Far East.

Scholars have noted the resemblance between U.S. policies in the Philippines and European actions in their

colonies in Asia and

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

during this period. By one contrast, however, the United States claimed to colonize in the name of anti-colonialism: "We are coming, Cuba, coming; we are bound to set you free! We are coming from the mountains, from the plains and inland sea! We are coming with the wrath of God to make the Spaniards flee! We are coming, Cuba, coming; coming now!"

Filipino revolutionary General

Emilio Aguinaldo

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (: March 22, 1869February 6, 1964) was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who became the first List of presidents of the Philippines, president of the Philippines (1899–1901), and the first pre ...

wondered: "The Filipinos fighting for Liberty, the American people fighting them to give them liberty. The two peoples are fighting on parallel lines for the same object." However, from 1898 until the

Cuban revolution

The Cuban Revolution () was the military and political movement that overthrew the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled Cuba from 1952 to 1959. The revolution began after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état, in which Batista overthrew ...

, The United States of America had significant influence over the economy of Cuba. By 1950, US investors owned 44 of the 161 sugar mills in Cuba, and slightly over 47% of total sugar output. By 1906, up to 15% of Cuba was owned by American landowners.

This consisted of 632,000 acres of sugar lands, 225,000 acres of tobacco, 700,000 of fruits and 2,750,000 acres of mining land, along with a quarter of the banking industry.

Industry and trade were two of the most prevalent justifications of imperialism.

American intervention in both Latin America and Hawaii resulted in multiple industrial investments, including the popular industry of

Dole bananas. If the United States was able to annex a territory, in turn they were granted access to the trade and capital of those territories. In 1898, Senator

Albert Beveridge

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert Computers, Inc., a computer manufacturer in the 1980s

* Albert Czech Republic, a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street mar ...

proclaimed that an expansion of markets was absolutely necessary, "American factories are making more than the American people can use; American soil is producing more than they can consume. Fate has written our policy for us; the trade of the world must and shall be ours."

American rule of ceded Spanish territory was not uncontested. The

Philippine Revolution

The Philippine Revolution ( or ; or ) was a war of independence waged by the revolutionary organization Katipunan against the Spanish Empire from 1896 to 1898. It was the culmination of the 333-year History of the Philippines (1565–1898), ...

had begun in August 1896 against Spain, and after the defeat of Spain in the

Battle of Manila Bay

The Battle of Manila Bay (; ), also known as the Battle of Cavite, took place on May 1, 1898, during the Spanish–American War. The American Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey engaged and destroyed the Spanish Pacific Squad ...

, began again in earnest, culminating in the

Philippine Declaration of Independence

The Philippine Declaration of Independence (; ) was proclaimed by Filipino revolutionary forces general Emilio Aguinaldo on June 12, 1898, in Cavite el Viejo (present-day Kawit, Cavite), Philippines. It asserted the sovereignty and indepe ...

and the establishment of the

First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Republic (), now officially remembered as the First Philippine Republic and also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was a state established in Malolos, Bulacan, during the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish ...

. The

Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

ensued, with extensive damage and death, ultimately resulting in the defeat of the Philippine Republic.

The United States' interests in Hawaii began in the 1800s with the United States becoming concerned that Great Britain or France might have colonial ambitions on the Hawaiian Kingdom. In 1849 the United States and The Kingdom of Hawaii signed a treaty of friendship removing any colonial ambitions Great Britain or France might have had. In 1885, King David Kalākaua, last king of Hawaii, signed a trade reciprocity treaty with the United States allowing for tariff free trade of sugar to the United States. The treaty was renewed in 1887 and with it came the overrunning of Hawaiian politics by rich, white, plantation owners. On July 6, 1887, the Hawaiian League, a non-native political group, threatened the king and forced him to sign a new constitution stripping him of much of his power. King Kalākaua would die in 1891 and be succeeded by his sister Lili'uokalani. In 1893 with support from marines from the USS ''Boston'' Queen Lili'uokalani would be deposed in a bloodless coup. Hawaii has been under US control ever since and became the 50th US state on August 21, 1959 in a joint resolution with Alaska.

Stuart Creighton Miller says that the public's sense of innocence about ''

Realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' ( ; ) is the approach of conducting diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly following ideological, moral, or ethical premises. In this respect, ...

'' impairs popular recognition of U.S. imperial conduct. The resistance to actively occupying foreign territory has led to policies of exerting influence via other means, including governing other countries via surrogates or

puppet regimes, where domestically unpopular governments survive only through U.S. support.

The Philippines is sometimes cited as an example. After Philippine independence, the US continued to direct the country through Central Intelligence Agency operatives like

Edward Lansdale

Edward Geary Lansdale (February 6, 1908 – February 23, 1987) was a United States Air Force officer until retiring in 1963 as a major general before continuing his work with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Lansdale was a pioneer in clande ...

. As

Raymond Bonner and other historians note, Lansdale controlled the career of President

Ramon Magsaysay

Ramon del Fierro Magsaysay Sr. (August 31, 1907 – March 17, 1957) was a Filipino statesman who served as the seventh President of the Philippines, from December 30, 1953, until his death in an 1957 Cebu Douglas C-47 crash, aircraft disast ...

, going so far as to physically beat him when the Philippine leader attempted to reject a speech the CIA had written for him. American agents also drugged sitting President

Elpidio Quirino

Elpidio Rivera Quirino (; November 16, 1890 – February 29, 1956) was a Philippine nationality law, Filipino lawyer and politician who served as the 6th President of the Philippines from 1948 to 1953.

A lawyer by profession, Quirino entered p ...

and prepared to assassinate Senator

Claro Recto. Prominent Filipino historian Roland G. Simbulan has called the CIA "US imperialism's

clandestine apparatus in the Philippines".

The U.S. retained dozens of military bases, including a few major ones. In addition, Philippine independence was qualified by legislation passed by the

U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the U.S. House of Representatives, and an upper body, the U.S. Senate. They both ...

. For example, the

Bell Trade Act

The Bell Trade Act of 1946, also known as the Philippine Trade Act, was an act passed by the United States Congress specifying policy governing trade between the Philippines and the United States following independence of the Philippines from the ...

provided a mechanism whereby U.S. import quotas might be established on Philippine articles which "are coming, or are likely to come, into substantial competition with like articles the product of the United States". It further required U.S. citizens and corporations be granted equal access to Philippine minerals, forests, and other natural resources. In hearings before the Senate Committee on Finance, Assistant Secretary of State for Economic Affairs

William L. Clayton described the law as "clearly inconsistent with the basic foreign economic policy of this country" and "clearly inconsistent with our promise to grant the Philippines genuine independence."

1918: Wilsonian intervention

When

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out in Europe, President

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

promised American neutrality throughout the war. This promise was broken when the United States entered the war after the

Zimmermann Telegram. This was "a war for empire" to control vast raw materials in Africa and other colonized areas, according to the contemporary historian and civil rights leader

W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

. More recently historian

Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922January 27, 2010) was an American historian and a veteran of World War II. He was chair of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, and a political science professor at Boston University. Zinn ...

argues that Wilson entered the war in order to open international markets to surplus US production. He quotes Wilson's own declaration that

In a memo to Secretary of State Bryan, the president described his aim as "an

open door to the world".

Lloyd Gardner notes that Wilson's original avoidance of world war was not motivated by anti-imperialism; his fear was that "

white civilization and its domination in the world" were threatened by "the great white nations" destroying each other in endless battle.

Despite President Wilson's official doctrine of

moral diplomacy seeking to "make the world safe for democracy," some of his

activities at the time can be viewed as imperialism to stop the advance of democracy in countries such as

Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

. The United States invaded

Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

on July 28, 1915, and American rule continued until August 1, 1934. The historian Mary Renda in her book, ''Taking Haiti'', talks about the American invasion of Haiti to bring about political stability through U.S. control. The American government did not believe Haiti was ready for self-government or democracy, according to Renda. In order to bring about political stability in Haiti, the United States secured control and integrated the country into the international capitalist economy, while preventing Haiti from practicing self-governance or democracy. While Haiti had been running their own government for many years before American intervention, the U.S. government regarded Haiti as unfit for self-rule. In order to convince the American public of the justice in intervening, the United States government used

paternalist

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy against their will and is intended to promote their own good. It has been defended in a variety of contexts as a means of protecting individuals from significant harm, s ...

propaganda, depicting the Haitian political process as uncivilized. The Haitian government would come to agree to U.S. terms, including American overseeing of the Haitian economy. This direct supervision of the Haitian economy would reinforce U.S. propaganda and further entrench the perception of Haitians' being incompetent of self-governance.

In World War I, the US, Britain, and Russia had been allies for seven months, from April 1917 until the

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s seized power in Russia in November. Active distrust surfaced immediately, as even before the

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

British officers had been involved in the

Kornilov Affair

The Kornilov affair, or the Kornilov putsch, was an attempted military coup d'état by the commander-in-chief of the Russian Army, General Lavr Kornilov, from 10 to 13 September 1917 ( O.S., 28–31 August), against the Russian Provisional Gov ...

, an attempted ''coup d'état'' by the Russian Army against the Provisional Government. Nonetheless, once the Bolsheviks took Moscow, the British government began talks to try and keep them in the war effort. British diplomat

Bruce Lockhart

The Bruce Lockhart family is of Scottish origins, and several members have played rugby football for Scotland, but since the early 20th century most have lived and worked in England or Canada, or else overseas, in India, Malaya, Australia, Russia ...

cultivated a relationship with several Soviet officials, including

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, and the latter approved the initial Allied military mission to secure the

Eastern Front, which was collapsing in the revolutionary upheaval. Ultimately, Soviet head of state

V.I. Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

decided the Bolsheviks would settle peacefully with the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

at the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

. This separate peace led to Allied disdain for the Soviets, since it left the

Western Allies

Western Allies was a political and geographic grouping among the Allied Powers of the Second World War. It primarily refers to the leading Anglo-American Allied powers, namely the United States and the United Kingdom, although the term has also be ...

to fight Germany without a strong Eastern partner. The

Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 (MI numbers, Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of Human i ...

, supported by US diplomat Dewitt C. Poole, sponsored an attempted coup in Moscow involving Bruce Lockhart and

Sidney Reilly

Sidney George Reilly (; – 5 November 1925), known as the "Ace of Spies", was a Russian-born adventurer and secret agent employed by Scotland Yard's Special Branch and later by the Foreign Section of the British Secret Service Bureau, the p ...

, which involved an attempted assassination of Lenin. The Bolsheviks proceeded to shut down the British and U.S. embassies.

Tensions between Russia (including its allies) and the West turned intensely ideological. Horrified by mass executions of White forces, land expropriations, and widespread repression, the Allied military expedition now

assisted the anti-Bolshevik Whites in the

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, with the US covertly giving support to the autocratic and antisemitic

General Alexander Kolchak.

Over 30,000 Western troops were deployed in Russia overall. This was the first event that made Russian–American relations a matter of major, long-term concern to the leaders in each country. Some historians, including

William Appleman Williams

William Appleman Williams (June 12, 1921 – March 5, 1990) was one of the 20th century's most prominent revisionist historians of American diplomacy. He achieved the height of his influence while on the faculty of the department of history at t ...

and

Ronald Powaski, trace the origins of the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

to this conflict.

Wilson launched seven armed interventions, more than any other president. Looking back on the Wilson era, General

Smedley Butler

Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940) was a United States Marine Corps officer and writer. During his 34-year military career, he fought in the Philippine–American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Mexican Revolution, World War I, ...

, a leader of the Haiti expedition and the highest-decorated Marine of that time, considered virtually all of the operations to have been economically motivated. In a

1933 speech he said:

1920s–1930s

Following World War I, the British maintained occupation of the Middle East, most notably Turkey and portions of formerly Ottoman territory following the empire's collapse.

[Quinn, J. W. (2009). ''American imperialism in the Middle East: 1920-1950'' (dissertation). Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC.] The occupation led to rapid industrialization, which resulted in the discovery of crude oil in Persia in 1908, sparking a boom in the Middle Eastern economy.

By the 1930s, the United States had cemented itself in the Middle East via a series of acquisitions through the

Standard Oil of California (SOCAL), which saw US control over Saudi oil.

It was clear to the US that further expansion in Middle Eastern oil would not be possible without diplomatic representation. In 1939, CASOC appealed to the US State Department about increasing political relations with

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

. This appeal was ignored until Germany and Japan made similar attempts following the start of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

1941–1945: World War II

At the start of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the US had multiple territories in the Pacific. The majority of these territories were military bases like Midway, Guam, Wake Island and Hawaii. Japan's surprise attack on

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

was what ended up bringing the United States into the war. Japan also launched multiple attacks on other American Territories like Guam and Wake Island. By early 1942 Japan also was able to take over the Philippine islands. At the end of the Philippine island campaign the general

MacArthur MacArthur or Macarthur may refer to:

Arts and media

* INSS MacArthur, a fictional starship featured in the science fiction novel ''The Mote in God's Eye''

* ''MacArthur'' (1977 film), a movie biography of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur

* ' ...

stated "I came through and I shall return" in response to the Americans losing the island to the Japanese. The loss of American territories ended the decisive

Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of t ...

. The Battle of Midway was the American offensive to stop Midway Island from falling into Japanese control. This led to the pushback of American forces and the recapturing of American territories. There were many battles that were fought against the Japanese which retook both allied territory as well as took over Japanese territories. In October 1944 American started their plan to retake the Philippine islands. Japanese troops on the island ended up surrendering in August 1945. After the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945, the United States occupied and reformed Japan up until 1952. The maximum geographical extension of American direct political and military control happened in the

aftermath of World War II

The aftermath of World War II saw the rise of two global superpowers, the United States (U.S.) and the Soviet Union (U.S.S.R.). The aftermath of World War II was also defined by the rising threat of nuclear warfare, the creation and implementati ...

, in the period after the surrender and occupations of

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

in May and later

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

and

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

in

September 1945 and before the United States granted the Philippines independence on

July 4, 1946.

The Grand Area

In an October 1940 report to Franklin Roosevelt, Bowman wrote that "the US government is interested in any solution anywhere in the world that affects American trade. In a wide sense, commerce is the mother of all wars." In 1942 this economic globalism was articulated as the "Grand Area" concept in secret documents. The US would have to have control over the "Western Hemisphere, Continental Europe and Mediterranean Basin (excluding Russia), the Pacific Area and the Far East, and the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

(excluding Canada)." The Grand Area encompassed all known major oil-bearing areas outside the Soviet Union, largely at the behest of corporate partners like the Foreign Oil Committee and the Petroleum Industry War Council. The US thus avoided overt territorial acquisition, like that of the European colonial empires, as being too costly, choosing the cheaper option of forcing countries to open their door to American business interests.

Although the United States was the last major belligerent to join the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, it began planning for the post-war world from the conflict's outset. This postwar vision originated in the

Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank focused on Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organi ...

(CFR), an economic elite-led organization that became integrated into the government leadership. CFR's

War and Peace Studies group offered its services to the State Department in 1939 and a secret partnership for post-war planning developed. CFR leaders

Hamilton Fish Armstrong

Hamilton Fish Armstrong (April 7, 1893 – April 24, 1973) was an American journalist who is known for editing ''Foreign Affairs'' from 1928 to 1972.

Early life

Armstrong was a member of the Fish Family of American politicians. His father w ...

and Walter H. Mallory saw World War II as a "grand opportunity" for the U.S. to emerge as "the premier power in the world."

This vision of empire assumed the necessity of the US to "police the world" in the aftermath of the war. This was not done primarily out of altruism, but out of economic interest.

Isaiah Bowman

Isaiah Bowman, AB, Ph. D. (December 26, 1878 – January 6, 1950), was an American geographer and President of the Johns Hopkins University, 1935–1948, controversial for his antisemitism and inaction in Jewish resettlement during World War ...

, a key liaison between the CFR and the State Department, proposed an "American economic

Lebensraum

(, ) is a German concept of expansionism and Völkisch movement, ''Völkisch'' nationalism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' beca ...

." This built upon the ideas of

Time-Life

Time Life, Inc. (also habitually represented with a hyphen as Time-Life, Inc., even by the company itself) was an American multi-media conglomerate company formerly known as a prolific production/publishing company and Direct marketing, direct ...

publisher

Henry Luce

Henry Robinson Luce (April 3, 1898 – February 28, 1967) was an American magazine magnate who founded ''Time'', ''Life'', '' Fortune'', and ''Sports Illustrated'' magazines. He has been called "the most influential private citizen in the Amer ...

, who (in his "

American Century

The American Century is a characterization of the period since the middle of the 20th century as being largely dominated by the United States in political, economic, technological, and cultural terms. It is comparable to the description of the p ...

" essay) wrote, "Tyrannies may require a large amount of living space

utfreedom requires and will require far greater living space than Tyranny." According to Bowman's biographer,

Neil Smith:

FDR promised: Hitler will get lebensraum, a global American one.

1947–1952: Cold War in Western Europe

Prior to his death in 1945, President Roosevelt was planning to withdraw all U.S. forces from Europe as soon as possible. Soviet actions in Poland and Czechoslovakia led his successor Harry Truman to reconsider. Heavily influenced by

George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

, Washington policymakers believed that the Soviet Union was an expansionary dictatorship that threatened American interests. In their theory, Moscow's weakness was that it had to keep expanding to survive; and that, by containing or stopping its growth, stability could be achieved in Europe. The result was the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

(1947). Initially regarding only Greece and Turkey, the

NSC-68 (1951) extended the Truman Doctrine to the whole non-Communist world. The United States could no longer distinguish between national and global security. Hence, the Truman Doctrine was described as "globalizing" the Monroe Doctrine.

A second equally important consideration was the need to restore the world economy, which required the rebuilding and reorganizing of Europe for growth. This matter, more than the Soviet threat, was the main impetus behind the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

of 1948.

A third factor was the realization, especially by Britain and the three

Benelux

The Benelux Union (; ; ; ) or Benelux is a politico-economic union, alliance and formal international intergovernmental cooperation of three neighbouring states in Western Europe: Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The name is a portma ...

nations, that American military involvement was needed.

Geir Lundestad

Geir Lundestad (17 January 1945 – 22 September 2023) was a Norwegian historian, who until 2014 served as the director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute when Olav Njølstad took over. In this capacity, he also served as the secretary of the Nor ...

has commented on the importance of "the eagerness with which America's friendship was sought and its leadership welcomed.... In Western Europe, America built an empire 'by invitation'" According to Lundestad, the

U.S. interfered in Italian and French politics in order to

purge elected communist officials who might oppose such invitations.

1950–1959: Cold War outside Europe

The end of the Second World War and start of the Cold War saw increased US interest in

Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

. Since the

Guatemalan Revolution

The period in the history of Guatemala between the coups against Jorge Ubico in 1944 and Jacobo Árbenz in 1954 is known locally as the Revolution (). It has also been called the Ten Years of Spring, highlighting the peak years of represen ...

, Guatemala saw the expansion of labour rights and

land reforms

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

which granted property to landless peasants. Lobbying by the

United Fruit Company

The United Fruit Company (later the United Brands Company) was an American multinational corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. The company was ...

, whose profits were affected by these policies, as well as fear of Communist influence in Guatemala culminated in the USA supporting

Operation PBFortune

Operation PBFortune, also known as Operation Fortune, was a covert United States operation to overthrow the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz in 1952. The operation was authorized by U.S. President Harry Truman and pla ...

to overthrow Guatemalan President

Jacobo Árbenz

Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (; 14 September 191327 January 1971) was a Guatemalan military officer and politician who served as the 25th president of Guatemala. He was Minister of National Defense from 1944 to 1950, before he became the secon ...

in 1952. The plan involved providing weapons to the exiled Guatemalan military officer

Carlos Castillo Armas