Types Of Zionism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The common definition of

The common definition of

Known in Hebrew as ''Tzionut Ma'asit'' (), Practical Zionism was led by

Known in Hebrew as ''Tzionut Ma'asit'' (), Practical Zionism was led by

Led by socialists

Led by socialists  In

In  In the 1920s, Labor Zionists in Palestine also created a trade union movement, the

In the 1920s, Labor Zionists in Palestine also created a trade union movement, the

Revisionist Zionism was initially led by

Revisionist Zionism was initially led by

"Temple Mount in Ruins"

/ref> Revolutionary Zionism generally espoused

The common definition of

The common definition of Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

was principally the endorsement of the Jewish people to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, secondarily the claim that due to a lack of self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, this territory must be re-established as a Jewish state

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland for the Jewish people.

Overview

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewi ...

. Historically, the establishment of a Jewish state has been understood in the Zionist mainstream as establishing and maintaining a Jewish majority. Zionism was produced by various philosophers representing different approaches concerning the objective and path that Zionism should follow. A "Zionist consensus" commonly refers to an ideological umbrella typically attributed to two main factors: a shared tragic history (such as the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

), and the common threat posed by Israel's neighboring enemies.

Political Zionism

Political Zionism aimed at establishing for the Jewish people a publicly and legally assured home inPalestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

through diplomatic negotiation with the established powers that controlled the area. It focused on a Jewish home as a solution to the "Jewish question

The Jewish question was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century Europe that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other " national questions", dealt with the civil, legal, national, ...

" and antisemitism in Europe, centred on gaining Jewish sovereignty (probably within the Ottoman or later British or French empire), and was opposed to mass migration until after sovereignty was granted. It initially considered locations other than Palestine (e.g. in Africa) and did not foresee migration by many Western Jews to the new homeland.

Nathan Birnbaum

Nathan Birnbaum (; pseudonyms: "Mathias Acher", "Dr. N. Birner", "Mathias Palme", "Anton Skart", "Theodor Schwarz", and "Pantarhei"; 25 April 1864 – 4 April 1937) was an Austrian writer and journalist, Jewish thinker and nationalist. His life ...

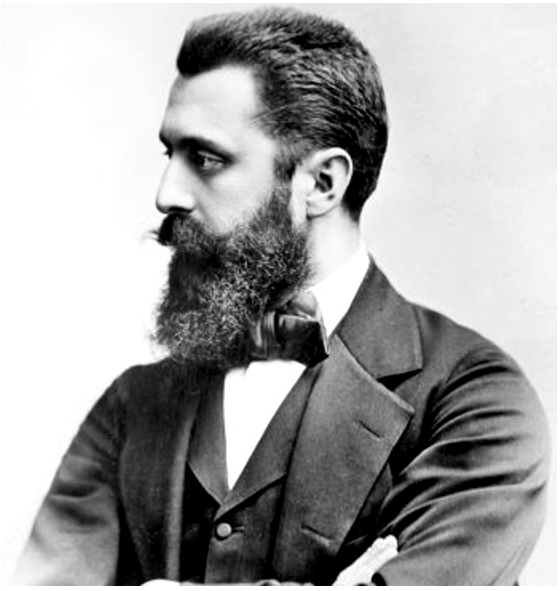

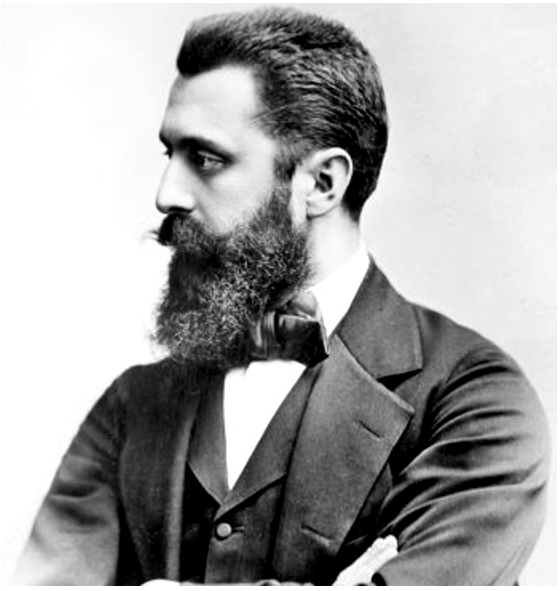

, a Jew from Vienna, was the original father of Political Zionism, yet ever since he defected away from his own movement, Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

has become known as the face of modern Zionism. In 1890, Birnbaum coined the term "Zionism" and the phrase "Political Zionism" two years later. Birnbaum published a periodical titled (''Self Emancipation'') which espoused "the idea of a Jewish renaissance and the resettlement of Palestine." In this idea, Birnbaum was most influenced by Leon Pinsker

Leon Pinsker or Judah Leib Pinsker (; ; – ) was a physician and Zionist activist.

Earlier in life he had originally supported the cultural assimilation of Jews in the Russian Empire. He was born in the town of Tomaszów Lubelski in the south ...

. Political Zionism was subsequently led by Herzl and Max Nordau

Max Simon Nordau (born Simon Maximilian Südfeld; 29 July 1849 – 23 January 1923) was a Hungarian Zionism, Zionist leader, physician, author, and Social criticism, social critic. He was a co-founder of the Zionist Organization together with Theo ...

. This approach was espoused at the Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization (; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the Zionist Organization (ZO; 1897–1960) at the initiative of Theodor Herzl at the F ...

's First Zionist Congress

The First Zionist Congress () was the inaugural congress of the Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization (ZO) held in the Stadtcasino Basel in the city of Basel on August 29–31, 1897. Two hundred and eight delegates from 17 countries and 2 ...

and dominated the movement during Herzl's life.

Practical Zionism

Known in Hebrew as ''Tzionut Ma'asit'' (), Practical Zionism was led by

Known in Hebrew as ''Tzionut Ma'asit'' (), Practical Zionism was led by Moshe Leib Lilienblum

Moshe Leib Lilienblum (; October 22, 1843, in Keidany, Kovno Governorate – February 12, 1910, in Odessa) was a Jewish scholar and author. He also used the pseudonym Zelophehad Bar-Hushim (). Lilienbloom was one of the leaders of the early Zioni ...

and Leon Pinsker

Leon Pinsker or Judah Leib Pinsker (; ; – ) was a physician and Zionist activist.

Earlier in life he had originally supported the cultural assimilation of Jews in the Russian Empire. He was born in the town of Tomaszów Lubelski in the south ...

and molded by the Hovevei Zion

The Lovers of Zion, also ''Hovevei Zion'' () or ''Hibbat Zion'' (, ), were a variety of proto-Zionist organizations founded in 1881 in response to the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire and were officially constituted as a group at a conf ...

organization. This approach believed that firstly there was a need in practical terms to implement Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel, Aliyah

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine (region), Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the Israel ...

, and settlement of the land, as soon as possible, even if a charter over the Land is not obtained.

It became dominant after Herzl's death, and differed from Political Zionism in not seeing Zionism as justified primarily by the Jewish Question but rather as an end in itself; it "aspired to the establishment of an elite utopian community in Palestine". It also differed from Political Zionism in "distrust nggrand political actions" and preferring "an evolutionary incremental process toward the establishment of the national home".

Labor Zionism

Led by socialists

Led by socialists Nachman Syrkin

Nachman Syrkin (also spelled ''Nahman Syrkin'' or ''Nahum Syrkin''; ; 11 February 1868 – 6 September 1924) was a political theorist, founder of Labor Zionism and a prolific writer in the Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, German and English languages.

...

, Haim Arlosoroff

Haim Arlosoroff (23 February 1899 – 16 June 1933; also known as Chaim Arlozorov; ) was a Socialist Zionist leader of the Yishuv during the British Mandate for Palestine, prior to the establishment of Israel, and head of the Political D ...

, and Berl Katznelson

Berl Katznelson (; 25 January 1887 – 12 August 1944) was one of the intellectual founders of Labor Zionism and was instrumental to the Israeli Declaration of Independence, establishment of the modern state of Israel. He was also the editor of ' ...

and Marxist Ber Borochov

Dov Ber Borochov (; – 17 December 1917) was a Marxist Zionist and one of the founders of the Labor Zionist movement. He was also a pioneer in the study of the Yiddish language.

Biography

Dov Ber Borochov was born in the town of Z ...

, Labor or socialist Zionists desired to establish an agricultural society not on the basis of a bourgeois capitalist society, but rather on the basis of equality. Labor or Socialist Zionism was a form of Zionism that also espoused socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

or social democratic

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

politics.

Although there were socialist Zionists in the nineteenth century (such as Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early socialist and Zionist thinker. His theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zionism.

Bi ...

), labor Zionism became a mass movement with the founding of Poale Zion

Poale Zion (, also romanized ''Poalei Tziyon'' or ''Poaley Syjon'', meaning "Workers of Zion") was a movement of Marxist–Zionist Jewish workers founded in various cities of Poland, Europe and the Russian Empire at about the turn of the 20th c ...

("Workers of Zion") groups in Eastern and Western Europe and North America in the 1900s. Other early socialist Zionist groups were the youth movement Hapoel Hatzair

Hapoel Hatzair (, "The Young Worker") was a Zionist group active in Palestine from 1905 until 1930. It was founded by A.D. Gordon, Yosef Aharonovich, Yosef Sprinzak and followed a non-Marxist, Zionist, socialist agenda. Hapoel Hatzair was a ...

founded by A. D. Gordon and Syrkin's Zionist Socialist Workers Party.

Socialist Zionism had a Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

current, led by Borochov. After 1917 (the year of Borochov's death as well as the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

and the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

), Poale Zion split between a Left (that supported Bolshevism

Bolshevism (derived from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined p ...

and then the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

) and a social democratic

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

Right (that became dominant in Palestine).

Ottoman Palestine

The region of Palestine (region), Palestine is part of the wider region of the Levant, which represents the land bridge between Africa and Eurasia.Steiner & Killebrew, p9: "The general limits ..., as defined here, begin at the Plain of ' ...

, Poale Zion founded the Hashomer

Hashomer (, 'The Watchman') was a Jewish defense organization in Palestine founded in April 1909. It was an outgrowth of the Bar-Giora group and was disbanded after the founding of the Haganah in 1920. Hashomer was responsible for guarding Je ...

guard organization that guarded settlements of the ''Yishuv

The Yishuv (), HaYishuv Ha'ivri (), or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el () was the community of Jews residing in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 2 ...

'', and took up the ideology of "conquest of labor" (''Kibbush Ha'avoda'') and " Hebrew labor" (''Avoda Ivrit''). It also gave birth to the youth movements Hashomer Hatzair

Hashomer Hatzair (, , 'The Young Guard') is a Labor Zionism, Labor Zionist, secular Jewish youth movement founded in 1913 in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary. It was also the name of the Hashomer Hatzair Workers Party, the ...

and Habonim Dror

Habonim Dror (, "the builders–freedom") is a Jewish Labor Zionist youth movement formed in 1982 through the merger of two earlier movements: Habonim and Dror.

Habonim (, "the builders") was established in 1929 in the United Kingdom and later e ...

. According to Ze'ev Sternhell, both Poalei Zion and Hapoel Hatzair believed that Zionism could only succeed as a result of constantly and rapidly expanding capitalist growth. Poale Zion "saw capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

as the cause of Jewish poverty and misery in Europe. For Poale Zion, Jews could only escape this cycle by creating a nation-state like others." However, according to Sternhell, Labor Zionism ultimately did not promise to free workers from the inherent dependencies of the capitalist system. In Labor Zionist thought, a revolution of the Jewish soul and society was necessary and achievable in part by Jews moving to Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

and becoming farmers, workers, and soldiers in a country of their own. Labor Zionists established rural communes in Israel called "kibbutz

A kibbutz ( / , ; : kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1910, was Degania Alef, Degania. Today, farming has been partly supplanted by other economi ...

im" which began as a variation on a "national farm" scheme, a form of cooperative agriculture where the Jewish National Fund

The Jewish National Fund (JNF; , ''Keren Kayemet LeYisrael''; previously , ''Ha Fund HaLeumi'') is a non-profit organizationProfessor Alon Tal, The Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology, The Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, Ben Gurion ...

hired Jewish workers under trained supervision. The kibbutzim were a symbol of the Second Aliyah

The Second Aliyah () was an aliyah (Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel) that took place between 1904 and 1914, during which approximately 35,000 Jews, mostly from Russia, with some from Yemen, immigrated into Ottoman Palestine.

The Sec ...

in that they put great emphasis on communalism and egalitarianism, representing Utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

to a certain extent. Furthermore, they stressed self-sufficiency, which became an essential aspect of Labor Zionism.

In the 1920s, Labor Zionists in Palestine also created a trade union movement, the

In the 1920s, Labor Zionists in Palestine also created a trade union movement, the Histadrut

Histadrut, fully the New General Workers' Federation () and until 1994 the General Federation of Labour in the Land of Israel (, ''HaHistadrut HaKlalit shel HaOvdim B'Eretz Yisrael''), is Israel's national trade union center and represents the m ...

, and political party, Mapai

Mapai (, an abbreviation for , ''Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael'', ) was a Labor Zionist and democratic socialist political party in Israel, and was the dominant force in Israeli politics until its merger into the Israeli Labor Party in January ...

. In Palestine, PZ disbanded to make way for the formation of the nationalist socialist Ahdut Ha'avoda, led by David Ben Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder and first prime minister of the State of Israel. As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, and later president of the Jewish Agency ...

, in 1919. Hapoel Hatzair merge with Ahdut Ha'avoda in 1930 to form Mapai, at which point, according to Yosef Gorny, Poale Zion became of marginal political importance in Palestine.

Labor Zionism, represented by Mapai, became the dominant force in the political and economic life of the Yishuv

The Yishuv (), HaYishuv Ha'ivri (), or HaYishuv HaYehudi Be'Eretz Yisra'el () was the community of Jews residing in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The term came into use in the 1880s, when there were about 2 ...

during the British Mandate of Palestine. Poale Zion's successor parties, Mapam

File:Pre-State_Zionist_Workers'_Parties_chart.png, chart of zionist workers parties, 360px, right

rect 167 83 445 250 Hapoel Hatzair

rect 450 88 717 265 The non-partisans (pre-state Zionist political movement), Non Partisans

rect 721 86 995 243 ...

, Mapai

Mapai (, an abbreviation for , ''Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael'', ) was a Labor Zionist and democratic socialist political party in Israel, and was the dominant force in Israeli politics until its merger into the Israeli Labor Party in January ...

and the Israeli Labor Party

The Israeli Labor Party (), commonly known in Israel as HaAvoda (), was a Social democracy, social democratic political party in Israel. The party was established in 1968 by a merger of Mapai, Ahdut HaAvoda and Rafi (political party), Rafi. Unt ...

(which were led by figures such as David Ben Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder and first prime minister of the State of Israel. As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, and later president of the Jewish Agency ...

and Golda Meir

Golda Meir (; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was the prime minister of Israel, serving from 1969 to 1974. She was Israel's first and only female head of government.

Born into a Jewish family in Kyiv, Kiev, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine) ...

, dominated Israeli politics until the 1977 election when the Israeli Labor Party

The Israeli Labor Party (), commonly known in Israel as HaAvoda (), was a Social democracy, social democratic political party in Israel. The party was established in 1968 by a merger of Mapai, Ahdut HaAvoda and Rafi (political party), Rafi. Unt ...

was defeated. Until the 1970s, the Histadrut was the largest employer in Israel after the Israeli government.

Sternhell and Benny Morris

Benny Morris (; born 8 December 1948) is an Israeli historian. He was a professor of history in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Beersheba, Israel. Morris was initially associated with the ...

both argue that Labor Zionism developed as a nationalist socialist movement in which the nationalist tendencies would overpower and drive out the socialist ones. Traditionalist Israeli historian Anita Shapira describes labor Zionism's use of violence against Palestinians for political means as essentially the same as that of radical conservative Zionist groups. For example, Shapira notes that during the 1936 Palestine revolt, the Irgun Zvai Leumi engaged in the "uninhibited use of terror", "mass indiscriminate killings of the aged, women and children", "attacks against British without any consideration of possible injuries to innocent bystanders, and the murder of British in cold blood". Shapira argues that there were only marginal differences in military behavior between the Irgun and the labor Zionist Palmah. In following with policies laid out by Ben-Gurion, the prevalent method among field squads was that if an Arab gang had used a village as a hideout, it was considered acceptable to hold the entire village collectively responsible. The lines delineating what was acceptable and unacceptable while dealing with these villagers were "vague and intentionally blurred". As Shapira suggests, these ambiguous limits practically did not differ from those of the openly terrorist group, Irgun.

Synthetic, General and Liberal Zionism

Synthetic Zionism, led byChaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( ; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization and later as the first pre ...

, Leo Motzkin and Nahum Sokolow

Nahum ben Joseph Samuel Sokolow ( ''Nachum ben Yosef Shmuel Soqolov'', ; 10 January 1859 – 17 May 1936) was a Jewish-Polish people, Polish writer, translator, and journalist, the fifth President of the World Zionist Organization, editor of ''H ...

, was an approach that advocated a combination of Political and Practical Zionism. It was the ideology of General Zionism, the centrist current between Labor Zionism and religious Zionism, that was initially the dominant trend within the Zionist movement from the First Zionist Congress in 1897 until after the First World War. General Zionists identified with the liberal European middle class to which many Zionist leaders such as Herzl and Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( ; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization and later as the first pre ...

aspired. As head of the World Zionist Organization, Weizmann's policies had a sustained impact on the Zionist movement, with Abba Eban describing him as a dominant figure in Jewish life during the interwar period. The current had a left wing (" General Zionists A"), who supported a mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

and good relations with Britain, and a right wing ("General Zionists B"), who were anti-socialist and anti-British. After independence, neither arm played a significant role in Israeli politics, the "A" group allying with Mapai and the "B" group forming a dwindling right-wing opposition party.

According to Zionist Israeli historian Simha Flapan, writing in the 1970s, the essential assumptions of Weizmann's strategy were later adopted by Ben-Gurion and subsequent Zionist (and Israeli) leaders. According to Flapan, by replacing "Great Britain" with "United States" and "Arab National Movement" with "Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

", Weizmann's strategic concepts can be seen as reflective of Israel's current foreign policy.

Weizmann's ultimate goal was the establishment of a Jewish state, even beyond the borders of "Greater Israel." For Weizmann, Palestine was a Jewish and not an Arab country. The state he sought would contain the east bank of the Jordan River and extend from the Litani River (in present-day Lebanon). Weizmann's strategy involved incrementally approaching this goal over a long period, in the form of settlement and land acquisition. Weizmann was open to the idea of Arabs and Jews jointly running Palestine through an elected council with equal representation, but he did not view the Arabs as equal partners in negotiations about the country's future. In particular, he was steadfast in his view of the "moral superiority" of the Jewish claim to Palestine over the Arab claim and believed these negotiations should be conducted solely between Britain and the Jews.

Liberal Zionism, although not associated with any single party in modern Israel, remains a strong trend in Israeli politics advocating free market principles, democracy and adherence to human rights. Their political arm was one of the ancestors of the modern-day Likud

Likud (, ), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement (), is a major Right-wing politics, right-wing, political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon in an alliance with several right-wing par ...

. Kadima

Kadima () was a centrist and liberal political party in Israel. It was established on 24 November 2005 by moderates from Likud largely following the implementation of Ariel Sharon's unilateral disengagement plan in August 2005, and was soon ...

, the main centrist party during the 2000s that split from Likud and is now defunct, however, did identify with many of the fundamental policies of Liberal Zionist ideology, advocating among other things the need for Palestinian statehood in order to form a more democratic society in Israel, affirming the free market, and calling for equal rights for Arab citizens of Israel.

Revisionist Zionism

Revisionist Zionism was initially led by

Revisionist Zionism was initially led by Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky (born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky; 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940) was a Russian-born author, poet, orator, soldier, and founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement and the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in O ...

and later by his successor Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'', ; (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of both Herut and Likud and the prime minister of Israel.

Before the creation of the state of Isra ...

(later Prime Minister of Israel

The prime minister of Israel (, Hebrew abbreviations, Hebrew abbreviation: ; , ''Ra'īs al-Ḥukūma'') is the head of government and chief executive of the Israel, State of Israel.

Israel is a parliamentary republic with a President of Isra ...

), and emphasized the romantic elements of Jewish nationality, and the historical heritage of the Jewish people in the Land of Israel as the constituent basis for the Zionist national idea and the establishment of the Jewish State. They supported liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

, particularly economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism ...

, and opposed Labor Zionism and the establishing of a communist society in the Land of Israel.

Jabotinsky founded the Revisionist Party in 1925. Jabotinsky rejected Weizmann's strategy of incremental state building, instead preferring to immediately declare sovereignty over the entire region, which extended to both the East and West bank of the Jordan river. Like Weizmann and Herzl, Jabotinsky also believed that the support of a great power was essential to the success of Zionism. From early on, Jabotinksy openly rejected the possibility of a "voluntary agreement" with the Arabs of Palestine. He instead believed in building an "iron wall" of Jewish military force to break Arab resistance to Zionism, at which point an agreement could be established.

Revisionist Zionists believed that a Jewish state must expand to both sides of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and drains to the Dead ...

, i.e. taking Transjordan in addition to all of Palestine. The movement developed what became known as Nationalist Zionism, whose guiding principles were outlined in the 1923 essay '' Iron Wall'', a term denoting the force needed to prevent Palestinian resistance against colonization. Jabotinsky wrote that

Historian Avi Shlaim

Avi Shlaim (, ; born 31 October 1945) is an Israeli and British historian of Iraqi Jewish descent. He is one of Israel's " New Historians", a group of Israeli scholars who put forward critical interpretations of the history of Zionism and Isr ...

describes Jabotinsky's perspective

In 1935 the Revisionists left the WZO because it refused to state that the creation of a Jewish state was an objective of Zionism. According to Israeli historian Yosef Gorny, the Revisionists remained within the ideological mainstream of the Zionist movement even after this split. The Revisionists advocated the formation of a Jewish Army in Palestine to force the Arab population to accept mass Jewish migration. Revisionist Zionism opposed any restraint in relation to Arab violence and supported firm military action against the Arabs that had attacked the Jewish Community in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

. Due to that position, a faction of the Revisionist leadership split from that movement in order to establish the underground Irgun

The Irgun (), officially the National Military Organization in the Land of Israel, often abbreviated as Etzel or IZL (), was a Zionist paramilitary organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine between 1931 and 1948. It was an offshoot of th ...

. This stream is also categorized as supporters of Greater Israel

Greater Israel (, ''Eretz Yisrael HaShlema'') is an expression with several different biblical and political meanings over time. It is often used, in an irredentist fashion, to refer to the historic or desired borders of Israel.

There are two d ...

.

Supporters of Revisionist Zionism developed the Likud

Likud (, ), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement (), is a major Right-wing politics, right-wing, political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon in an alliance with several right-wing par ...

Party in Israel, which has dominated most governments since 1977. It advocates Israel's maintaining control of the West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, including East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem (, ; , ) is the portion of Jerusalem that was Jordanian annexation of the West Bank, held by Jordan after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as opposed to West Jerusalem, which was held by Israel. Captured and occupied in 1967, th ...

, and takes a hard-line approach in the Arab–Israeli conflict. In 2005, Likud split over the issue of creation of a Palestinian state in the occupied territories. Party members advocating peace talks helped form the Kadima Party.

Religious Zionism

Initially led byYitzchak Yaacov Reines

Yitzchak Yaacov Reines (, Isaac Jacob Reines), (October 27, 1839 – August 20, 1915) was a Lithuanian Orthodox rabbi and the founder of the Mizrachi Religious Zionist Movement, one of the earliest movements of Religious Zionism, as well as ...

, founder of the Mizrachi movement, and by Abraham Isaac Kook

Abraham Isaac HaCohen Kook (; 7 September 1865 – 1 September 1935), known as HaRav Kook, and also known by the Hebrew-language acronym Hara'ayah (), was an Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox rabbi, and the first Ashkenazi Jews, Ashkenazi Chief Rabbina ...

, Religious Zionism is a variant of Zionist ideology that combines religious conservatism and secular nationalism into a theology with patriotism as its basis. Before the establishment of the state of Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, Religious Zionists were mainly observant Jews who supported Zionist efforts to build a Jewish state

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland for the Jewish people.

Overview

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewi ...

in the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definition ...

. Religious Zionism maintained that Jewish nationality and the establishment of the State of Israel is a religious duty derived from the Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

. As opposed to some parts of the Jewish non-secular community that claimed that the redemption of the Land of Israel will occur only after the coming of the messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

, who will fulfill this aspiration, they maintained that human acts of redeeming the Land will bring about the messiah, as their slogan states: "The land of Israel for the people of Israel according to the Torah of Israel" (). One of the core ideas in Religious Zionism is the belief that the ingathering of exiles in the Land of Israel and the establishment of Israel is Atchalta De'Geulah ("the beginning of the redemption"), the initial stage of the ''geula

Geula ( lit. ''Redemption'') is a neighborhood in the center of Jerusalem, populated mainly by Haredi Judaism, Haredi Jews. Geula is bordered by Zikhron Moshe and Mekor Baruch on the west, the Bukharim neighborhood on the north, Mea Shearim on t ...

''. Their ideology revolves around three pillars: the Land of Israel, the People of Israel and the Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

of Israel.

The Labor Movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

wing of Religious Zionism, founded in 1921 under the Zionist slogan "Torah va'Avodah" (Torah and Labor), was called HaPoel HaMizrachi

File:Pre-State_Zionist_Workers'_Parties_chart.png, chart of zionist workers parties, 360px, right

rect 167 83 445 250 Hapoel Hatzair

rect 450 88 717 265 Non Partisans

rect 721 86 995 243 Poalei Zion

rect 152 316 373 502 HaPoel HaMizrachi

rec ...

. It represented religiously traditional Labour Zionists, both in Europe and in the Land of Israel, where it represented religious Jews in the Histadrut

Histadrut, fully the New General Workers' Federation () and until 1994 the General Federation of Labour in the Land of Israel (, ''HaHistadrut HaKlalit shel HaOvdim B'Eretz Yisrael''), is Israel's national trade union center and represents the m ...

. In 1956, Mizrachi, HaPoel HaMizrachi, and other religious Zionists formed the National Religious Party

The National Religious Party (, ''Miflaga Datit Leumit''), commonly known in Israel by its Hebrew abbreviation Mafdal (), was an Israeli political party representing the interests of the Israeli settlers and religious Zionist movement.

Formed ...

(NRP), which operated as an independent political party until the 2003 elections.

After the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

and the capture of the West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, a territory referred to by the movement as Judea and Samaria, the movement turned right as it integrated revanchist and irredentist forms of nationalism and evolved into what is sometimes known as Neo-Zionism. In the current period, this right-wing form of religious Zionism, powerful within the settlement movement, is represented by Gush Emunim

Gush Emunim (, lit. "Bloc of the Faithful") was an Israeli ultranationalist religious Zionist Orthodox Jewish right-wing fundamentalist activist movement committed to establishing Jewish settlements in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and the Golan ...

(founded by students of Abraham Kook's son Zvi Yehuda Kook in 1974), Jewish Home

The Jewish Home () was an Orthodox Jewish, religious Zionist and far-right political party in Israel. It was originally formed by a merger of the National Religious Party, Moledet and Tkuma in November 2008. However, Moledet broke away from t ...

(HaBayit HaYehudi, formed in 2009), Tkuma, and Meimad. Today they are commonly referred as the "Religious Nationalists" or the "settlers

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a Human settlement, settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among ...

", and are also categorized as supporters of Greater Israel

Greater Israel (, ''Eretz Yisrael HaShlema'') is an expression with several different biblical and political meanings over time. It is often used, in an irredentist fashion, to refer to the historic or desired borders of Israel.

There are two d ...

.

Kahanism

Kahanism () is a religious Zionist ideology based on the views of Rabbi Meir Kahane, founder of the Jewish Defense League and the Kach party in Israel. Kahane held the view that most Arabs living in Israel are the enemies of Jews and Israel ...

, a radical branch of religious Zionism, was founded by Rabbi Meir Kahane

Meir David HaKohen Kahane ( ; ; born Martin David Kahane; August 1, 1932 – November 5, 1990) was an American-born Israel, Israeli Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox ordained rabbi, writer and ultra-nationalist politician. Founder of the Israeli pol ...

, whose party, Kach

Kach () was a radical Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox Jewish, religious Zionist List of political parties in Israel, political party in Israel, existing from 1971 to 1994. Founded by Rabbi Meir Kahane in 1971 based on his Jewish-Orthodox-nationalist ...

, was eventually banned from the Knesset, but has been increasingly influential on Israeli politics. The Otzma Yehudit

Otzma Yehudit () is a Far-right politics in Israel, far-right, ultranationalist, Kahanism, Kahanist, and Anti-Arab racism, anti-Arab List of political parties in Israel, political party in Israel. It is the ideological descendant of the outlawe ...

(Jewish Power) party, which espouses Kahanism, won six seats in the 2022 Israeli legislative election

Legislative elections were held in Israel on 1 November 2022 to elect the 120 members of the 25th Knesset. The results saw the right-wing national camp of former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu win a parliamentary majority, amid losses for ...

, forming what has been called the most right-wing government in Israeli history.

Cultural Zionism

Cultural Zionism or Spritual Zionism is a strain of Zionism that focused on creating a center in historic Palestine with its own secularJewish culture

Jewish culture is the culture of the Jewish people, from its formation in ancient times until the current age. Judaism itself is not simply a faith-based religion, but an orthopraxy and Ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligion, pertaining to deed, ...

and national history, including language and historical roots, rather than on mass migration or state-building. The founder of Cultural Zionism was Asher Ginsberg, better known as Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am (, lit. 'one of the people', ), was a Hebrew journalist and essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zionist thinkers. ...

. Like Hibbat Zion and unlike Herzl, Ha'am saw Palestine as the spritual centre of Jewish life. Ha'am inaugurated the movement in his 1880 essay "This is not the way", which called for the cultivation of a qualitative Jewish presence in the land over hequantitative one" pursued by Hibbat Zion. Ha'am was also a sharp critic of Herzl; spiritual Zionism believed that the realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' ( ; ) is the approach of conducting diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly following ideological, moral, or ethical premises. In this respect, ...

engaged in by Political Zionism corrupted Jewry, and opposed any political solutions that victimised non-Jewish people in the land.

Brit Shalom, which promoted Arab-Jewish cooperation, was established in 1925 by supporters of Ahad Ha'am's Spiritual Zionism, including Martin Buber

Martin Buber (; , ; ; 8 February 1878 – 13 June 1965) was an Austrian-Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I and Thou, I–Thou relationship and the I� ...

, Gershom Scholem

Gershom Scholem (; 5 December 1897 – 21 February 1982) was an Israeli philosopher and historian. Widely regarded as the founder of modern academic study of the Kabbalah, Scholem was appointed the first professor of Jewish mysticism at Hebrew Un ...

, Hans Kohn

Hans Kohn, (September 15, 1891 – March 16, 1971) was an American philosopher and historian. He pioneered the academic study of nationalism, and is considered an authority on the subject.

Life

Kohn was born into a German-speaking Jewish family i ...

, "and other important figures of the intellectual elite of the pre-independence ''yishuv'', Gorny describes it as an ultimately marginal group.

Revolutionary Zionism

Led byAvraham Stern

Avraham Stern (, ''Avraham Shtern''; December 23, 1907 – February 12, 1942), alias Yair (), was one of the leaders of the Jewish paramilitary organization Irgun. In September 1940, he founded a breakaway militant Zionist group named Lehi, c ...

, Israel Eldad and Uri Zvi Greenberg

Uri Zvi Greenberg (; September 22, 1896 – May 8, 1981; also spelled Uri Zvi Grinberg) was an Israeli poet, journalist and politician who wrote in Yiddish and Hebrew.

Widely regarded among the greatest poets in the country's history, he was a ...

. Revolutionary Zionism viewed Zionism as a revolutionary struggle to ingather the Jewish exiles from the Diaspora, revive the Hebrew language as a spoken vernacular and reestablish a Jewish kingdom in the Land of Israel. As members of Lehi during the 1940s, many adherents of Revolutionary Zionism engaged in guerilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrorism ...

against the British administration in an effort to end the British Mandate of Palestine and pave the way for Jewish political independence. Following the State of Israel's establishment leading figures of this stream argued that the creation of the state of Israel was never the goal of Zionism but rather a tool to be used in realizing the goal of Zionism, which they called ''Malkhut Yisrael'' (the Kingdom of Israel). Revolutionary Zionists are often mistakenly included among Revisionist Zionists but differ ideologically in several areas. While Revisionists were for the most part secular nationalists who hoped to achieve a Jewish state that would exist as a commonwealth within the British Empire, Revolutionary Zionists advocated a form of national-messianism that aspired towards a vast Jewish kingdom with a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. Accord ...

.Israel Eldad, ''Israel: The Road to Full Redemption'', p. 37 (Hebrew) and Israel Eldad"Temple Mount in Ruins"

/ref> Revolutionary Zionism generally espoused

anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influenc ...

political views and included both Right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

and Left-wing nationalists among its adherents. This stream is also categorized as supporters of Greater Israel

Greater Israel (, ''Eretz Yisrael HaShlema'') is an expression with several different biblical and political meanings over time. It is often used, in an irredentist fashion, to refer to the historic or desired borders of Israel.

There are two d ...

.

Reform Zionism

Reform Zionism, also known as Progressive Zionism, is the ideology of theZionist

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

arm of the Reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

or Progressive branch of Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

. The Association of Reform Zionists of America is the American Reform movement's Zionist organization. Their mission "endeavors to make Israel fundamental to the sacred lives and Jewish identity

Jewish identity is the objective or subjective sense of perceiving oneself as a Jew and as relating to being Jewish. It encompasses elements of nationhood, "The Jews are a nation and were so before there was a Jewish state of Israel" "Jews are ...

of Reform Jews. As a Zionist organization, the association champions activities that further enhance Israel as a pluralistic, just and democratic Jewish state." In Israel, Reform Zionism is associated with the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism.

Other types

*Christian Zionism

Christian Zionism is a political and religious ideology that, in a Christianity and Judaism, Christian context, espouses the return of the Jews, Jewish people to the Holy Land. Likewise, it holds that the founding of the State of Israel in 1948 ...

* Federal Zionism

* Green Zionism

See also

*Anti-Zionism

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the Palestine (region) ...

* Autonomism

Autonomism or ''autonomismo'', also known as autonomist Marxism or autonomous Marxism, is an anti-capitalist social movement and Marxist-based theoretical current that first emerged in Italy in the 1960s from workerism (). Later, post-Marxist ...

* Bundism

Bundism () is a Jewish socialist movement that emerged in Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to promote working class politics, secularism, and foster Jewish political and cultural autonomy. As a part of that autonomism, it also sought to ...

* Canaanism

Canaanism was a cultural and ideological movement founded in 1939, reaching its peak among the Jews of Mandatory Palestine during the 1940s. It has had a significant effect on the course of Israeli art, literature and spiritual and political t ...

* Diaspora nationalism

* Folkism

* Neo-Zionism

* Non-Zionism

Non-Zionism is the political stance of Jews who are "willing to help support Jewish settlement in Palestine... but will not come on aliyah."David Polish, ''Prospects for Post-Holocaust Zionism'', in Moshe David (editor), ''Zionism in Transition'', ...

* Post-Zionism

* Proto-Zionism

* Territorialism

Territorialism can refer to:

* Animal territorialism, the animal behavior of defending a geographical area from intruders

* Environmental territorialism, a stance toward threats posed toward individuals, communities or nations by environmental even ...

* Yiddishism

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Zion and State: Nation, Class and the Shaping of Modern Israel by Mitchell Cohen * {{DEFAULTSORT:Types of Zionism Zionism Jewish movements