Tychonian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish

In 1588, Tycho's royal benefactor died, and a volume of Tycho's great two-volume work (''Introduction to the New Astronomy'') was published. The first volume, devoted to the new star of 1572, was not ready, because the reduction of the observations of 1572–73 involved much research to correct the stars' positions for

In 1588, Tycho's royal benefactor died, and a volume of Tycho's great two-volume work (''Introduction to the New Astronomy'') was published. The first volume, devoted to the new star of 1572, was not ready, because the reduction of the observations of 1572–73 involved much research to correct the stars' positions for

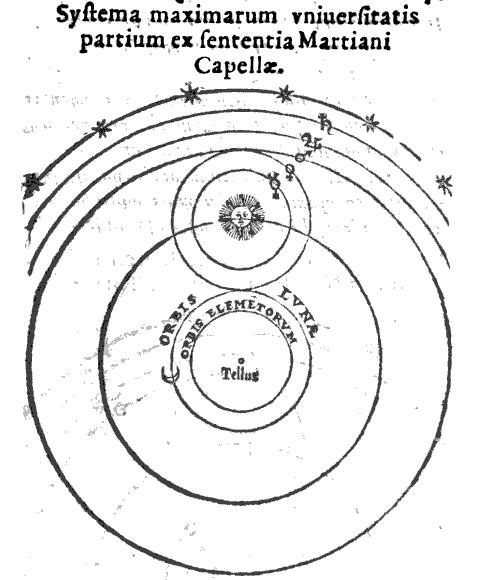

Although Tycho admired Copernicus and was the first to teach his theory in Denmark, he was unable to reconcile Copernican theory with the basic laws of Aristotelian physics, which he believed to be foundational. He was critical of the observational data that Copernicus built his theory on, which he correctly considered to be inaccurate. Instead, Tycho proposed a "geo-heliocentric" system in which the Sun and Moon orbited the Earth, while the other planets orbited the Sun. His system had many of the observational and computational advantages of Copernicus' system. It provided a safe position for those astronomers who were dissatisfied with older models, but reluctant to accept heliocentrism.

It gained a following after 1616, when the Catholic Church declared the heliocentric model to be contrary to philosophy and Christian

Although Tycho admired Copernicus and was the first to teach his theory in Denmark, he was unable to reconcile Copernican theory with the basic laws of Aristotelian physics, which he believed to be foundational. He was critical of the observational data that Copernicus built his theory on, which he correctly considered to be inaccurate. Instead, Tycho proposed a "geo-heliocentric" system in which the Sun and Moon orbited the Earth, while the other planets orbited the Sun. His system had many of the observational and computational advantages of Copernicus' system. It provided a safe position for those astronomers who were dissatisfied with older models, but reluctant to accept heliocentrism.

It gained a following after 1616, when the Catholic Church declared the heliocentric model to be contrary to philosophy and Christian

Galileo's 1610 telescopic discovery that Venus shows a full set of phases refuted the pure geocentric Ptolemaic model. After that it seems 17th-century astronomy mostly converted to geo-heliocentric planetary models that could explain these phases just as well as the heliocentric model could, but without the latter's disadvantage of the failure to detect any annual stellar parallax that Tycho and others regarded as refuting it.

The three main geo-heliocentric models were the Tychonic, the Capellan with just Mercury and Venus orbiting the Sun such as favoured by

Galileo's 1610 telescopic discovery that Venus shows a full set of phases refuted the pure geocentric Ptolemaic model. After that it seems 17th-century astronomy mostly converted to geo-heliocentric planetary models that could explain these phases just as well as the heliocentric model could, but without the latter's disadvantage of the failure to detect any annual stellar parallax that Tycho and others regarded as refuting it.

The three main geo-heliocentric models were the Tychonic, the Capellan with just Mercury and Venus orbiting the Sun such as favoured by  The ardent anti-heliocentric French astronomer Jean-Baptiste Morin devised a Tychonic planetary model with elliptical orbits published in 1650 in a simplified, Tychonic version of the ''Rudolphine Tables''. Another geocentric French astronomer,

The ardent anti-heliocentric French astronomer Jean-Baptiste Morin devised a Tychonic planetary model with elliptical orbits published in 1650 in a simplified, Tychonic version of the ''Rudolphine Tables''. Another geocentric French astronomer,

The first biography of Tycho, which was also the first full-length biography of any scientist, was written by Gassendi in 1654. In 1779, Tycho de Hoffmann wrote of Tycho's life in his history of the Brahe family. In 1913, Dreyer published Tycho's collected works, facilitating further research. Early modern scholarship on Tycho tended to see the shortcomings of his astronomical model, painting him as a mysticist recalcitrant in accepting the Copernican revolution, and valuing mostly his observations that allowed Kepler to formulate his laws of planetary movement. Especially in Danish scholarship, Tycho was depicted as a mediocre scholar and a traitor to the nationperhaps because of the important role in Danish historiography of Christian IV as a warrior king.

In the second half of the 20th century, scholars began reevaluating his significance, and studies by Kristian Peder Moesgaard, Owen Gingerich, Robert Westman, Victor E. Thoren, John R. Christianson and C. Doris Hellman focused on his contributions to science, and demonstrated that while he admired Copernicus he was simply unable to reconcile his basic theory of physics with the Copernican view. Christianson's work showed the influence of Tycho's Uraniborg as a training center for scientists who after studying with Tycho went on to make contributions in various scientific fields.

The first biography of Tycho, which was also the first full-length biography of any scientist, was written by Gassendi in 1654. In 1779, Tycho de Hoffmann wrote of Tycho's life in his history of the Brahe family. In 1913, Dreyer published Tycho's collected works, facilitating further research. Early modern scholarship on Tycho tended to see the shortcomings of his astronomical model, painting him as a mysticist recalcitrant in accepting the Copernican revolution, and valuing mostly his observations that allowed Kepler to formulate his laws of planetary movement. Especially in Danish scholarship, Tycho was depicted as a mediocre scholar and a traitor to the nationperhaps because of the important role in Danish historiography of Christian IV as a warrior king.

In the second half of the 20th century, scholars began reevaluating his significance, and studies by Kristian Peder Moesgaard, Owen Gingerich, Robert Westman, Victor E. Thoren, John R. Christianson and C. Doris Hellman focused on his contributions to science, and demonstrated that while he admired Copernicus he was simply unable to reconcile his basic theory of physics with the Copernican view. Christianson's work showed the influence of Tycho's Uraniborg as a training center for scientists who after studying with Tycho went on to make contributions in various scientific fields.

Tycho's discovery of the new star was the inspiration for

Tycho's discovery of the new star was the inspiration for

''De Mundi Aetherei Recentioribus Phaenomenis Liber Secundus''

(Uraniborg, 1588; Prague, 1603; Frankfurt, 1610)

''Tychonis Brahe Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata''

(Prague, 1602/03; Frankfurt, 1610) *

Information about the opening of Brahe's tomb in 2010

from

The Noble Dane: Images of Tycho Brahe

', an exhibition by the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford in 2004

The Correspondence of Tycho Brahe

from the Bodleian Library's Early Modern Letters Online website

''Astronomiae instauratae mechanica'', 1602 edition

from Lehigh University

archived

20 December 2022)

''Learned Tico Brahae, His Astronomicall Coniectur'', 1632

– full digital facsimile, Linda Hall Library

Coat-of-arms of Brahe

on the island of Ven (Sweden)

''De Nova Stella''

– English translation of the astronomy sections, freely available fro

causaScientia.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brahe, Tycho Tycho Brahe, Brahe family, * 1546 births 1601 deaths 16th-century alchemists 16th-century Danish astronomers 16th-century writers in Latin Astronomical instrument makers Christian astrologers Copernican Revolution Danish alchemists Danish astrologers Danish Lutherans Danish printers Danish publishers (people) Danish science writers Danish scientific instrument makers Discoverers of supernovae Leipzig University alumni Papermakers People from Svalöv Municipality People without noses Philippists University of Copenhagen alumni University of Rostock alumni

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observation

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical ...

s. He was known during his lifetime as an astronomer, astrologer

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, and alchemist

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

. He was the last major astronomer before the invention of the telescope

The history of the telescope can be traced to before the invention of the earliest known telescope, which appeared in 1608 in the Netherlands, when a patent was submitted by Hans Lippershey, an eyeglass maker. Although Lippershey did not recei ...

. Tycho Brahe has also been described as the greatest pre-telescopic astronomer.

In 1572, Tycho noticed a completely new star that was brighter than any star or planet. Astonished by the existence of a star that ought not to have been there, he devoted himself to the creation of ever more accurate instruments of measurement over the next fifteen years (1576–1591). King Frederick II granted Tycho an estate on the island of Hven

Ven (, older Swedish spelling ''Hven''), is a Swedish island in the Öresund strait laying between Scania, Sweden and Zealand, Denmark. A part of Landskrona Municipality, Skåne County, the island has an area of and 371 inhabitants as of 2020. ...

and the money to build Uraniborg

Uraniborg was an astronomical observatory and alchemy laboratory established and operated by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. It was the first custom-built observatory in modern Europe, and the last to be built without a telescope as its pr ...

, the first large observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysics, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed.

Th ...

in Christian Europe. He later worked underground at Stjerneborg, where he realised that his instruments in Uraniborg were not sufficiently steady. His unprecedented research program both turned astronomy into the first modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as al ...

and also helped launch the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

.

An heir to several noble families, Tycho was well educated. He worked to combine what he saw as the geometrical

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

benefits of Copernican heliocentrism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical scientific modeling, model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting arou ...

with the philosophical benefits of the Ptolemaic system

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

, and devised the Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the universe published by Tycho Brahe in 1588, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican heliocentrism, Copernican system with the philosophical and "physic ...

, his own version of a model of the Universe, with the Sun orbiting the Earth, and the planets as orbiting the Sun. In (1573), he refuted the Aristotelian belief in an unchanging celestial realm. His measurements indicated that "new stars", , now called ''supernova

A supernova (: supernovae or supernovas) is a powerful and luminous explosion of a star. A supernova occurs during the last stellar evolution, evolutionary stages of a massive star, or when a white dwarf is triggered into runaway nuclear fusion ...

e'', moved beyond the Moon, and he was able to show that comets were not atmospheric phenomena, as was previously thought.

In 1597, Tycho was forced by the new king, Christian IV

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years and 330 days is the longest in Scandinavian history.

A member of the H ...

, to leave Denmark. He was invited to Prague, where he became the official imperial astronomer, and built an observatory at Benátky nad Jizerou

Benátky nad Jizerou (; ) is a town in Mladá Boleslav District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 7,900 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected as an urban monument zone.

Administr ...

. Before his death in 1601, he was assisted for a year by Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

, who went on to use Tycho's data to develop his own three laws of planetary motion.

Life

Family

Tycho Brahe was born as heir to several of Denmark's most influential noble families. In addition to his immediate ancestry with theBrahe

The Brahe family (originally ''Bragde'') refers to two closely related noble families of Scanian origin that played significant roles in both Danish and Swedish history. The Danish branch became extinct in 1786, and the Swedish branch in 193 ...

and the Bille families, he counted the Rud, Trolle

The House of Trolle is the name of a noble family, originally from Sweden. The family has produced prominent people in the histories of Sweden and Denmark (where it is sometimes spelled ) since the Middle Ages and is associated with several esta ...

, Ulfstand

The Ulfstand family was a Danish, mostly Scania

Scania ( ), also known by its native name of Skåne (), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces () of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of ...

, and Rosenkrantz

Rosenkranz is the Danish and German word for rosary. The literal German meaning is 'wreath of roses'.

Rosenkranz, Rosenkrantz, Rosencrance, Rosencrans or Rosencrantz is a Germanic and Ashkenazi Jewish surname and may refer to:

People

* Rosenkran ...

families among his ancestors. Both of his grandfathers and all of his great-grandfathers had served as members of the Danish king's Privy Council. His paternal grandfather and namesake, Thyge Brahe, was the lord of Tosterup Castle

Tosterup Castle () is a castle in Tomelilla Municipality, Scania, in southern Sweden. It is situated approximately north-east of Ystad

Ystad () is a town and the seat of Ystad Municipality, in Scania County, Sweden. Ystad had 18,350 inhabi ...

in Scania and died in battle during the 1523 Siege of Malmö during the Lutheran Reformation Wars.

His maternal grandfather, Claus Bille

Claus Bille (ca. 1490 – 4 January 1558 at Lyngsgård, Scania) was a Danish landlord and statesman.

Early life

Claus was born as the youngest son of a Danish nobleman, Steen Basse Torbensen Bille of Søholm (1446–1520) and his wife, Margr ...

, lord to Bohus Castle and a second cousin of Swedish king Gustav Vasa

Gustav Eriksson Vasa (12 May 1496 – 29 September 1560), also known as Gustav I, was King of Sweden from 1523 until his death in 1560. He was previously self-recognised Protector of the Realm (''Reichsverweser#Sweden, Riksföreståndare'') fr ...

, participated in the Stockholm Bloodbath

The Stockholm Bloodbath () was a trial that led to a series of executions in Stockholm between 7 and 9 November 1520. The event is also known as the Stockholm massacre.

The events occurred after the coronation of Christian II as the new king of ...

on the side of the Danish king against the Swedish nobles. Tycho's father, Otte Brahe

Otte Brahe (; 2 October 1518 – 9 May 1571) was a Danes, Danish (Scanian) Danish nobility, nobleman and statesman, who served on the privy council (Rigsraad, "Council of the Realm"). He was married to Beate Clausdatter Bille and was the father o ...

, a royal Privy Councilor (like his own father), married Beate Bille, a powerful figure at the Danish court holding several royal land titles. Tycho's parents are buried under the floor of the church of Kågeröd

Kågeröd is a locality situated in Svalöv Municipality, Skåne County, Sweden with 1,446 inhabitants in 2010.

The permanent motor circuit Ring Knutstorp

Ring Knutstorp is a Motorsport, motor racing Race track, circuit in Kågeröd, Sweden. ...

, four kilometres west of Knutstorp Castle

Knutstorp Castle () is a manor house situated in the Svalöv Municipality of Scania, Sweden.

History

A manor already in the middle of the 14th century, it was owned by the Danish Brahe noble family from the end of the Middle Ages until 1663, a ...

.

Early years

Tycho was born on 14 December 1546, at his family's ancestral seat at Knutstorp (; ), about north ofSvalöv

Svalöv () is a locality and the seat of Svalöv Municipality, Skåne County, Sweden with 3,633 inhabitants in 2010. It is around north of Malmö

Malmö is the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, third-largest city in Sweden, after ...

in then Danish Scania

Scania ( ), also known by its native name of Skåne (), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces () of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous w ...

. He was the oldest of 12 siblings, 8 of whom lived to adulthood, including Steen Brahe and Sophia Brahe

Sophia (or Sophie) Thott Lange (; 24 August 1559 or 22 September 1556probably in 1559 following , some others scholars give 1556, both dates match his horoscope (Det Kongelige Bibliotek). – 1643), known by her maiden name, was a Danish noble ...

. His twin brother died before being baptized

Baptism (from ) is a Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by sprinkling or pouring water on the head, or by immersing in water either partially or completely, traditionally three ...

. Tycho later wrote an ode in Latin to his dead twin, which was printed in 1572 as his first published work. An epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

, originally from Knutstorp, but now on a plaque near the church door, shows the whole family, including Tycho as a boy.

When he was only two years old Tycho was taken away to be raised by his uncle Jørgen Thygesen Brahe

Jørgen Thygesen Brahe (''Jørgen Brahe til Tostrup i Skåne'') (1515 – 21 June 1565) was a member of the Danish nobility. Biography

He was the son of Danish Councillor Thyge Axelsen Brahe til Tostrup (d. 1523) and brother of privy counci ...

and his wife Inger Oxe

Inger Johansdatter Oxe ( - 1591) was a Danish noblewoman and court official. She was Hofmesterinde to the Danish Queen Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow between 1572 and 1584.

She was the sister to Peder Oxe Steward of the Realm, daughter of Johan ...

, sister to Peder Oxe

Peder Oxe (''Peder Oxe til Nielstrup''; 7 January 1520 – 24 October 1575) was a Danish finance minister and Steward of the Realm.

Background

At the age of twelve he was sent abroad to complete his education, and resided at the principal univ ...

, Steward of the Realm, who were childless. It is unclear why Otte Brahe reached this arrangement with his brother, but Tycho was the only one of his siblings not to be raised by his mother at Knutstorp. Instead, Tycho was raised at Jørgen Brahe's estate at Tosterup

Tosterup Castle () is a castle in Tomelilla Municipality, Scania, in southern Sweden. It is situated approximately north-east of Ystad.

Owners

List of owners of Tosterup Castle:

*Early 1300s – Axel Eskildsen Mule

*1300s – His daughter Barb ...

and at Tranekær on the island of Langeland

Langeland (, ) is a Danish island located between the Great Belt and Bay of Kiel. The island measures 285 km2 (c. 110 square miles) and, as of 1 January 2018, has a population of 12,446.

, and later at Næsbyhoved Castle near Odense

Odense ( , , ) is the third largest city in Denmark (after Copenhagen and Aarhus) and the largest city on the island of Funen. As of 1 January 2025, the city proper had a population of 185,480 while Odense Municipality had a population of 210, ...

, and later again at the Castle of Nykøbing on the island of Falster

Falster () is an island in south-eastern Denmark with an area of and 43,398 inhabitants as of 1 January 2010.

. Tycho later wrote that Jørgen Brahe "raised me and generously provided for me during his life until my eighteenth year; he always treated me as his own son and made me his heir".

From ages 6 to 12, Tycho attended Latin school, probably in Nykøbing. At age 12, on 19 April 1559, Tycho began studies at the University of Copenhagen

The University of Copenhagen (, KU) is a public university, public research university in Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Founded in 1479, the University of Copenhagen is the second-oldest university in Scandinavia, after Uppsala University.

...

. There, following his uncle's wishes, he studied law, but also studied a variety of other subjects and became interested in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

. At the university, Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

was a staple of scientific theory, and Tycho likely received a thorough training in Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural philosophy described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies ...

and cosmology. He experienced the solar eclipse of 21 August 1560, and was greatly impressed by the fact that it had been predicted, although the prediction based on current observational data was a day off. He realized that more accurate observations would be the key to making more exact predictions. He purchased an ephemeris

In astronomy and celestial navigation, an ephemeris (; ; , ) is a book with tables that gives the trajectory of naturally occurring astronomical objects and artificial satellites in the sky, i.e., the position (and possibly velocity) over tim ...

and books on astronomy, including Johannes de Sacrobosco

Johannes de Sacrobosco, also written Ioannes de Sacro Bosco, later called John of Holywood or John of Holybush ( 1195 – 1256), was a scholar, Catholic monk, and astronomer who taught at the University of Paris.

He wrote a short introductio ...

's , Petrus Apianus

Petrus Apianus (April 16, 1495 – April 21, 1552), also known as Peter Apian, Peter Bennewitz, and Peter Bienewitz, was a German humanist, known for his works in mathematics, astronomy and cartography. His work on " cosmography", the field that d ...

's and Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrument ...

's .

Jørgen Thygesen Brahe, however, wanted Tycho to educate himself in order to become a civil servant, and sent him on a study tour of Europe in early 1562. Fifteen-year-old Tycho was given as mentee to the 19-year-old Anders Sørensen Vedel

Anders Sørensen Vedel (9 November 1542 – 13 February 1616) At 14 years old, he moved to study in Ribe, and after finishing his education he moved on to Copenhagen University in 1561. In 1562, he was the tutor of astronomer Tycho Brahe on Brahe' ...

. Tycho eventually talked Vedel into allowing him to pursue astronomy during the tour. Vedel and his pupil left Copenhagen in February 1562. On 24 March, they arrived in Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, where they matriculated at the Lutheran Leipzig University

Leipzig University (), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December 1409 by Frederick I, Electo ...

. In 1563, he observed a close conjunction of the planets Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

and Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant, with an average radius of about 9 times that of Earth. It has an eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 tim ...

, and noticed that the Copernican and Ptolemaic tables used to predict the conjunction were inaccurate. This led him to realise that progress in astronomy required systematic, rigorous observation, night after night, using the most accurate instruments obtainable. He began maintaining detailed journals of all his astronomical observations. In this period, he combined the study of astronomy with astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, laying down horoscopes for different famous personalities.

When Tycho and Vedel returned from Leipzig in 1565, Denmark was at war with Sweden, and as vice-admiral of the Danish fleet, Jørgen Brahe had become a national hero for having participated in the sinking of the Swedish warship ''Mars'' during the First battle of Öland (1564). Shortly after Tycho's arrival in Denmark, Jørgen Brahe was defeated in the action of 4 June 1565

This battle took place on 4 June 1565 between an allied fleet of 33 Danish and Lübecker ships, under Trolle, and a Swedish fleet of around 49 ships, under Klas Horn. Afterward, the Danes retired to Køge Bay, south of Copenhagen, where Trolle ...

, and shortly afterwards died of a fever. Stories have it that he contracted pneumonia after a night of drinking with the Danish King Frederick II when the king fell into the water in a Copenhagen canal and Brahe jumped in after him. Brahe's possessions passed on to his wife Inger Oxe, who considered Tycho with special fondness.

Tycho's nose

In 1566, Tycho left to study at theUniversity of Rostock

The University of Rostock () is a public university located in Rostock, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. Founded in 1419, it is the third-oldest university in Germany. It is the oldest university in continental northern Europe and the Baltic Se ...

in what is now Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. There he studied with professors of medicine at the university's famous medical school and became interested in medical alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

and herbal medicine

Herbal medicine (also called herbalism, phytomedicine or phytotherapy) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. Scientific evidence for the effectiveness of many herbal treatments ...

. On 29 December 1566 at the age of 20, Tycho lost part of his nose in a sword duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapons.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and later the small sword), but beginning in ...

with a fellow Danish nobleman, his third cousin Manderup Parsberg. At an engagement party at the home of Professor Lucas Bachmeister on 10 December the two had drunkenly quarreled over who was the superior mathematician. On 29 December, the cousins resolved their feud with a duel in the dark. Though the two were later reconciled, in the duel Tycho lost the bridge of his nose and gained a broad scar across his forehead.

He received the best possible care at the university and wore a prosthetic nose for the rest of his life. It was kept in place with paste

Paste is a term for any very thick viscous fluid. It may refer to:

Science and technology

* Adhesive or paste

** Wallpaper paste

** Wheatpaste, a liquid adhesive made from vegetable starch and water

* Paste (rheology), a substance that behaves as ...

or glue and said to be made of silver and gold. In November 2012, Danish and Czech researchers reported that the prosthesis was actually made of brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

after chemically analyzing a small bone sample from the nose from the body exhumed in 2010. The prostheses made of gold and silver were mostly worn for special occasions, rather than everyday wear.

Science and life on Uraniborg

In April 1567, Tycho returned home from his travels, with a firm intention of becoming an astrologer. Although he had been expected to go into politics and the law, like most of his kinsmen, and although Denmark was still at war with Sweden, his family supported his decision to dedicate himself to the sciences. His father wanted him to take up law, but Tycho was allowed to travel toRostock

Rostock (; Polabian language, Polabian: ''Roztoc''), officially the Hanseatic and University City of Rostock (), is the largest city in the German States of Germany, state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and lies in the Mecklenburgian part of the sta ...

and then to Augsburg

Augsburg ( , ; ; ) is a city in the Bavaria, Bavarian part of Swabia, Germany, around west of the Bavarian capital Munich. It is a College town, university town and the regional seat of the Swabia (administrative region), Swabia with a well ...

, where he built a great quadrant

Quadrant may refer to:

Companies

* Quadrant Cycle Company, 1899 manufacturers in Britain of the Quadrant motorcar

* Quadrant (motorcycles), one of the earliest British motorcycle manufacturers, established in Birmingham in 1901

* Quadrant Privat ...

, then Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

, and Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau or simply Freiburg is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fourth-largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. Its built-up area has a population of abou ...

. In 1568, he was appointed a canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the material accepted as officially written by an author or an ascribed author

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western canon, th ...

at Roskilde Cathedral

Roskilde Cathedral (), in the city of Roskilde on the island of Zealand (Denmark), Zealand (''Sjælland'') in eastern Denmark, is a cathedral of the Lutheranism, Lutheran Church of Denmark.

The cathedral is one of the most important churches in D ...

, a largely honorary position that allowed him to focus on his studies.

At the end of 1570, he was informed of his father's ill health, so he returned to Knutstorp Castle, where his father died on 9 May 1571. The war was over, and the Danish lords soon returned to prosperity. Soon, another uncle, Steen Bille, helped him build an observatory and alchemical laboratory at Herrevad Abbey

Herrevad Abbey () was a Cistercian monastery near Ljungbyhed in Klippan Municipality, Scania, in the south of present-day Sweden, but formerly in Denmark until 1658. It is now a country house known as Herrevad Castle ().

History

Herrevad A ...

, where Tycho was assisted by his keenest disciple, his younger sister Sophie Brahe. Tycho was acknowledged by King Frederick II, who proposed to him that an observatory be built to better study the night sky. After accepting this proposal, the location for the Uraniborg's construction was set on an island called Hven, now Ven in the Sound not too far from Copenhagen, the earliest large observatory in Christian Europe.

Tycho Brahe was highly appreciated by King Frederick II, and he was accepted and supported by people of high social status. He was supported by the church. The support Tycho Brahe received from the king allowed him to continue his research and make significant contributions to the field of astronomy.

In the late 16th century, Tycho Brahe built an observatory called Uraniborg. It was built on the island of Hven located between the provinces of Zealand (Sjælland) and Scania (Skåne). The island was then an administrative part of Zealand. Later, after the Peace of Roskilde in 1658, Scania was conquered by the Swedes. In 1660, Hven became part of Sweden. In Tycho's time, it was all Denmark. He lived on Hven for approximately 21 years. He began to build Uraniborg in 1576 and moved there soon after. As Uraniborg was a significant and advanced observatory, it took years to complete.Christianson, J. R. (2020). "Star Castle: Going Down to See Up". In ''Tycho Brahe and the measure of the heavens'' (pp. 118–159). essay, Reaktion Books.

Uraniborg was a place where Tycho Brahe could research and analyze his previous findings, as well as explore new discoveries. Tycho Brahe was an astronomer of the pre-telescope era. Using just his naked eye, he observed the planets, Moon, stars, and space and recorded everything he saw while completing a multitude of calculations daily. The location of Uraniborg was strategically chosen, with seclusion and support being the primary reasons for building on the island of Hven. Seclusion was essential for accurate observation, and gave Tycho Brahe a better way to focus on his work without worrying about interruptions from other people. Seclusion was also important for observation, as there was nothing interfering with time, light, or motion observations.

Tycho Brahe was a perfectionist, and by being secluded he had complete control over his research and was not limited by anyone else's restrictions, enabling him to develop innovative research. He could focus all of his energy on his work, without receiving any backlash or questioning from anyone. The seclusion gave him the freedom to pursue his research without limitations and paved the way for groundbreaking discoveries in the field of astronomy. Uraniborg was one of the most advanced observatories of its time, equipped with several astronomical instruments, including quadrant instruments, sextants, and astronomical clocks.

Tycho Brahe's observations and calculations at Uraniborg allowed him to develop more accurate Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

models. He compiled the most extensive and accurate catalog of stellar positions up to that time. Tycho Brahe's observations and calculations at Uraniborg allowed him to lay the groundwork for astronomers in the future.

Despite the success Tycho Brahe had on Hven, he eventually left the island after a disagreement with the new king of Denmark, Christian IV. In 1597, Tycho Brahe moved to Prague, where he continued his work and was eventually appointed by Emperor Rudolf II in 1601 as imperial mathematician. However, Uraniborg remained a significant landmark in the history of astronomy.

Morganatic marriage to Kirsten Jørgensdatter

Towards the end of 1571, Tycho fell in love with Kirsten, daughter of Jørgen Hansen, theLutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

minister in Knudstrup. As she was a commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

, Tycho never formally married her, since if he did he would lose his noble privileges. However, Danish law permitted morganatic marriage

Morganatic marriage, sometimes called a left-handed marriage, is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which in the context of royalty or other inherited title prevents the principal's position or privileges being passed to the spou ...

, which meant that a nobleman and a common woman could live together openly as husband and wife for three years, and their alliance then became a legally binding marriage. However, each would maintain their social status, and any children they had together would be considered commoners, with no rights to titles, landholdings, coat of arms, or even their father's noble name.

While King Frederick respected Tycho's choice of wife, himself having been unable to marry the woman he loved, many of Tycho's family members disagreed, and many churchmen continued to hold the lack of a divinely sanctioned marriage against him. Kirsten Jørgensdatter gave birth to their first daughter, Kirstine, named after Tycho's late sister, on 12October 1573. Kirstine died from the plague in 1576. Tycho wrote a heartfelt elegy for her tombstone. In 1574, they moved to Copenhagen where their daughter Magdalene was born. Later the family followed him into exile. Kirsten and Tycho lived together for almost thirty years until Tycho's death. Together, they had eight children, six of whom lived to adulthood.

1572 supernova

On 11 November 1572, Tycho observed, from Herrevad Abbey, a very bright star, now numberedSN 1572

SN 1572 ('' Tycho's Star'', ''Tycho's Nova'', ''Tycho's Supernova''), or B Cassiopeiae (B Cas), was a supernova of Type Ia in the constellation Cassiopeia, one of eight supernovae visible to the naked eye in historical records. It appeared in e ...

, which had unexpectedly appeared in the constellation Cassiopeia

Cassiopeia or Cassiopea may refer to:

Greek mythology

* Cassiopeia (mother of Andromeda), queen of Aethiopia and mother of Andromeda

* Cassiopeia (wife of Phoenix), wife of Phoenix, king of Phoenicia

* Cassiopeia, wife of Epaphus, king of Egy ...

. Because it had been maintained since antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

that the world beyond the Moon's orbit was eternally unchangeable, with celestial immutability being a fundamental axiom of the Aristotelian world-view, other observers held that the phenomenon was something in the terrestrial sphere below the Moon. However, Tycho observed that the object showed no daily parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different sightline, lines of sight and is measured by the angle or half-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to perspective (graphica ...

against the background of the fixed stars. This implied that it was at least farther away than the Moon and those planets that do show such parallax. He found that the object did not change its position relative to the fixed stars over several months, as all planets did in their periodic orbital motions, even the outer planets, for which no daily parallax was detectable.

This suggested that it was not even a planet, but a fixed star in the stellar sphere beyond all the planets. In 1573, he published a small book , coining the term nova

A nova ( novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. All observed novae involve white ...

for a "new" star. This star was a supernova

A supernova (: supernovae or supernovas) is a powerful and luminous explosion of a star. A supernova occurs during the last stellar evolution, evolutionary stages of a massive star, or when a white dwarf is triggered into runaway nuclear fusion ...

and is 7,500 light-year

A light-year, alternatively spelled light year (ly or lyr), is a unit of length used to express astronomical distances and is equal to exactly , which is approximately 9.46 trillion km or 5.88 trillion mi. As defined by the International Astr ...

s from Earth. This discovery was decisive for his choice of astronomy as a profession. Tycho was strongly critical of those who dismissed the implications of the astronomical appearance, writing in the preface to : ("O thick wits. O blind watchers of the sky"). The publication of his discovery made him a well-known name among scientists in Europe.

Lord of Hven

Tycho continued with his detailed observations, often assisted by his first assistant and student, his younger sisterSophie

Sophie is a feminine given name, another version of Sophia, from the Greek word for "wisdom".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Soph ...

. In 1574, Tycho published the observations made in 1572 from his first observatory at Herrevad Abbey. He then started lecturing on astronomy, but gave it up and left Denmark in spring 1575 to tour abroad. He first visited William IV, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

William IV of Hesse-Kassel (24 June 153225 August 1592), also called ''William the Wise'', was the first Landgrave of the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel). He was the founder of the oldest line, which survives to this day.

Life

L ...

's observatory at Kassel, then went on to Frankfurt, Basel, and Venice, where he acted as an agent for the Danish king, contacting artisans and craftsmen whom the king wanted to work on his new palace at Elsinore. Upon his return, the King wished to repay Tycho's service by offering him a position worthy of his family. He offered him a choice of lordships of militarily and economically important estates, such as the castles of Hammershus

Hammershus is a medieval era fortification at Hammeren on the northern tip of the Danish island of Bornholm.

The fortress was partially demolished around 1750 and is now a ruin. It was partially restored around 1900.

History

Hammershus was Sc ...

or Helsingborg

Helsingborg (, , ), is a Urban areas in Sweden, city and the seat of Helsingborg Municipality, Scania County, Scania (Skåne), Sweden. It is the second-largest city in Scania (after Malmö) and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, ninth ...

.

Tycho was reluctant to take up a position as a lord of the realm, preferring to focus on his science. He wrote to his friend Johannes Pratensis, "I did not want to take possession of any of the castles our benevolent king so graciously offered me. I am displeased with society here, customary forms and the whole rubbish". Tycho secretly began to plan to move to Basel, wishing to participate in the burgeoning academic and scientific life there. The King heard of Tycho's plans, and desiring to keep the distinguished scientist, in 1576 he offered Tycho the island of Hven

Ven (, older Swedish spelling ''Hven''), is a Swedish island in the Öresund strait laying between Scania, Sweden and Zealand, Denmark. A part of Landskrona Municipality, Skåne County, the island has an area of and 371 inhabitants as of 2020. ...

in Øresund

Øresund or Öresund (, ; ; ), commonly known in English as the Sound, is a strait which forms the Denmark–Sweden border, Danish–Swedish border, separating Zealand (Denmark) from Scania (Sweden). The strait has a length of ; its width var ...

and funding to set up an observatory.

Until then, Hven had been property directly under the Crown. The 50 families on the island considered themselves to be freeholding farmers, but with Tycho's appointment as Feudal Lord of Hven, this changed. Tycho took control of agricultural planning, requiring the peasants to cultivate twice as much as they had done before, and he exacted corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid forced labour that is intermittent in nature, lasting for limited periods of time, typically only a certain number of days' work each year. Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state (polity), state for the ...

labor from the peasants for the construction of his new castle. The peasants complained about Tycho's excessive taxation and took him to court. The court established Tycho's right to levy taxes and labor. The result was a contract detailing the mutual obligations of lord and peasants on the island.

Tycho envisioned his castle Uraniborg

Uraniborg was an astronomical observatory and alchemy laboratory established and operated by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. It was the first custom-built observatory in modern Europe, and the last to be built without a telescope as its pr ...

as a temple dedicated to the muse

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, the Muses (, ) were the Artistic inspiration, inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the poetry, lyric p ...

s of arts and sciences, rather than as a military fortress. It was named after Urania

Urania ( ; ; modern Greek shortened name ''Ránia''; meaning "heavenly" or "of heaven") was, in Greek mythology, the muse of astronomy and astrology. Urania is the goddess of astronomy and stars, her attributes being the globe and compass.

T ...

, the muse of astronomy. Construction began in 1576, with a laboratory for his alchemical

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

experiments in the cellar. Uraniborg was inspired by the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be on ...

. It was one of the first buildings in northern Europe to show influence from Italian renaissance architecture.

When he realized that the towers of Uraniborg were not adequate as observatories, because of the instruments' exposure to the elements and the movement of the building, he constructed an underground observatory close to Uraniborg called Stjerneborg (Star Castle) in 1584. This consisted of several hemispherical crypts which contained the great equatorial armillary, large azimuth quadrant, zodiacal armillary, largest azimuth quadrant of steel and the trigonal sextant.

The basement of Uraniborg included an alchemical laboratory, with 16 furnaces for conducting distillations and other chemical experiments. Unusually for the time, Tycho established Uraniborg as a research centre, where almost 100 students and artisans worked from 1576 to 1597. Uraniborg contained a printing press and a paper mill, both among the first in Scandinavia, enabling Tycho to publish his own manuscripts, on locally made paper with his own watermark

A watermark is an identifying image or pattern in paper that appears as various shades of lightness/darkness when viewed by transmitted light (or when viewed by reflected light, atop a dark background), caused by thickness or density variations i ...

. He created a system of ponds and canals to run the wheels of the paper mill. Another resident of Uraniborg was a man with dwarfism

Dwarfism is a condition of people and animals marked by unusually small size or short stature. In humans, it is sometimes defined as an adult height of less than , regardless of sex; the average adult height among people with dwarfism is . '' ...

named Jeppe, whom Tycho believed had the ability to predict the future, and he allegedly was able to correctly predict the chances of recovery or death of ill people in Hven.

Over the years he worked on Uraniborg, Tycho was assisted by a number of students and protegés, many of whom went on to their own careers in astronomy. Among them were Christian Sørensen Longomontanus

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words ''Christ'' and ''Ch ...

, later one of the main proponents of the Tychonic model and Tycho's replacement as royal Danish astronomer, Peder Flemløse, Elias Olsen Morsing, and Cort Aslakssøn

Cort Aslakssøn (28 June 1564 – 7 February 1624) was a Norwegian astronomer, theologist and philosopher. He was the first Norwegian to become a professor at the University of Copenhagen.

Biography

Aslakssøn was born in Bergen, Norway. H ...

. Tycho's instrument-maker Hans Crol formed part of the scientific community on the island.

Great Comet of 1577

Tycho observed thegreat comet

A great comet is a comet that becomes exceptionally bright. There is no official definition; often the term is attached to comets such as Halley's Comet, which during certain appearances are bright enough to be noticed by casual observers who ar ...

that was visible in the Northern sky from November 1577 to January 1578. Within Lutheranism, it was commonly believed that celestial objects like comets were powerful portents, announcing the coming apocalypse. Several Danish amateur astronomers observed the object and published prophesies of impending doom. Tycho was able to determine that the comet's distance to Earth was much greater than the distance of the Moon, so that the comet could not have originated in the "earthly sphere", confirming his prior anti-Aristotelian conclusions about the fixed nature of the sky beyond the Moon.

Tycho realized that the comet's tail

The tail is the elongated section at the rear end of a bilaterian animal's body; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage extending backwards from the midline of the torso. In vertebrate animals that evolution, evolved to los ...

was always pointing away from the Sun. He calculated its diameter, mass, and the length of its tail, and speculated about the material it was made of. Through nightly observations of the comet, Tycho Brahe estimated its closest approach to Earth at about 230 times the Earth's radius. He also analyzed its motion, suggesting an orbit located between Mercury and Venus.

At this point, he had not yet broken with Copernican heliocentrism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical scientific modeling, model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting arou ...

, and observing the comet inspired him to try to develop an alternative Copernican model, in which the Earth was immobile. Tycho Brahe's comet observations challenged the prevailing theory of solid celestial spheres. With the comet likely traveling between Mercury and Venus, the notion of these rigid spheres became untenable. It suggested a vast emptiness where objects like the comet, potentially quite large, could move freely and exhibit properties unlike those previously understood. The second half of his manuscript about the comet dealt with the astrological and apocalyptic aspects of the comet. Tycho rejected the prophesies of his competitors. Instead, he made his own predictions of dire political events in the near future. Among his predictions was bloodshed in Moscow, and the imminent fall of Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

by 1583.

Support from the Crown

The support that Tycho received from the Crown was substantial, amounting to 1% of the annual total revenue at one point in the 1580s. Tycho often held large social gatherings in his castle.Pierre Gassendi

Pierre Gassendi (; also Pierre Gassend, Petrus Gassendi, Petrus Gassendus; 22 January 1592 – 24 October 1655) was a French philosopher, Catholic priest, astronomer, and mathematician. While he held a church position in south-east France, he a ...

wrote that Tycho had a tame elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

and that his mentor the Landgrave

Landgrave (, , , ; , ', ', ', ', ') was a rank of nobility used in the Holy Roman Empire, and its former territories. The German titles of ', ' ("margrave"), and ' ("count palatine") are of roughly equal rank, subordinate to ' ("duke"), and su ...

Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, also known as the Hessian Palatinate (), was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. The state was created in 1567 when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided upon t ...

asked whether there was an animal faster than a deer. Tycho replied that there was none, but he could send his tame elk. When Wilhelm replied he would accept one in exchange for a horse, Tycho replied with the sad news that the elk had just died on a visit to entertain a nobleman at Landskrona

Landskrona is a town in Scania, Sweden. Located on the shores of the Öresund, it occupies a natural port, which has lent the town at first military and subsequent commercial significance. Ferries operate from Landskrona to the island of Ven, an ...

. Apparently, during dinner, the elk had drunk a lot of beer, fallen down the stairs, and died.

Among the many noble visitors to Hven was James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

, who married the Danish princess Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

. He gave gold coins to the ferryman and to the builders and workers at Tycho's paper mill. After his visit to Hven in 1590, James wrote a poem comparing Tycho with Apollon and Phaethon

Phaethon (; , ), also spelled Phaëthon, is the son of the Oceanids, Oceanid Clymene (mother of Phaethon), Clymene and the solar deity, sun god Helios in Greek mythology.

According to most authors, Phaethon is the son of Helios who, out of a de ...

.

As part of Tycho's duties to the Crown, in exchange for his estate, he fulfilled the functions of a royal astrologer. At the beginning of each year, he had to present an Almanac to the court, predicting the influence of the stars on the political and economic prospects of the year. At the birth of each prince, he prepared their horoscopes, predicting their fates. He also worked as a cartographer with his former tutor Anders Sørensen Vedel on mapping out all of the Danish realm. An ally of the king and friendly with Queen Sophie, both his mother Beate Bille and adoptive mother Inger Oxe had been her court maids, he secured a promise from the King that ownership of Hven and Uraniborg would pass to his heirs.

Publications, correspondence and scientific disputes

In 1588, Tycho's royal benefactor died, and a volume of Tycho's great two-volume work (''Introduction to the New Astronomy'') was published. The first volume, devoted to the new star of 1572, was not ready, because the reduction of the observations of 1572–73 involved much research to correct the stars' positions for

In 1588, Tycho's royal benefactor died, and a volume of Tycho's great two-volume work (''Introduction to the New Astronomy'') was published. The first volume, devoted to the new star of 1572, was not ready, because the reduction of the observations of 1572–73 involved much research to correct the stars' positions for refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

, precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In o ...

, the motion of the Sun etc., and was not completed in Tycho's lifetime. It was published in Prague in 1602–1603.

The second volume, titled (''Second Book About Recent Phenomena in the Celestial World'') and devoted to the comet of 1577, was printed at Uraniborg and some copies were issued in 1588. Besides the comet observations, it included an account of Tycho's system of the world. The third volume was intended to treat the comets of 1580 and following years in a similar manner. It was never published, or written, though a great deal of material about the comet of 1585 was put together and published in 1845 with the observations of this comet.

While at Uraniborg, Tycho maintained correspondence with scientists and astronomers across Europe. He inquired about other astronomers' observations and shared his own technological advances to help them achieve more accurate observations. Thus, his correspondence was crucial to his research. Often, correspondence was not just private communication between scholars, but also a way to disseminate results and arguments and to build progress and scientific consensus. Through correspondence, Tycho was involved in several personal disputes with critics of his theories. Prominent among them were John Craig, a Scottish physician who was a strong believer in the authority of the Aristotelian worldview, and Nicolaus Reimers Baer, known as Ursus, an astronomer at the Imperial court in Prague, whom Tycho accused of having plagiarized his cosmological model.

Craig refused to accept Tycho's conclusion, that the comet of 1577 had to be located within the aetherial sphere, rather than within the atmosphere of Earth. Craig tried to contradict Tycho by using his own observations of the comet, and by questioning his methodology. Tycho published an ''apologia'' (a defense) of his conclusions, in which he provided additional arguments, as well as condemning Craig's ideas in strong language for being incompetent. Another dispute concerned the mathematician Paul Wittich, who, after staying on Hven in 1580, taught Count Wilhelm of Kassel and his astronomer Christoph Rothmann

Christoph Rothmann (between 1550 and 1560 in Bernburg, Saxony-Anhalt – probably after 1600 in Bernburg) was a German mathematician and one of the few well-known astronomers of his time. His research contributed substantially to the fact that Ka ...

to build copies of Tycho's instruments without permission from Tycho. Craig, who had studied with Wittich, accused Tycho of minimizing Wittich's role in developing some of the trigonometric methods used by Tycho. In his dealings with these disputes, Tycho made sure to leverage his support in the scientific community, by publishing and disseminating his own answers and arguments.

Exile and later years

When Frederick died in 1588, his son and heirChristian IV

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years and 330 days is the longest in Scandinavian history.

A member of the H ...

was only 11 years old. A regency council was appointed to rule for the young prince-elect until his coronation in 1596. The head of the council (Steward of the Realm) was Christoffer Valkendorff

Christoffer Valkendorff (1 September 152517 January 1601) was a Danish-Norwegian statesman and landowner. His early years in the service of Frederick II brought him both to Norway, Ösel and Livland. He later served both as Treasurer and '' St ...

, who disliked Tycho after a conflict between them, and hence Tycho's influence at the Danish court steadily declined. Feeling that his legacy on Hven was in peril, he approached the Dowager Queen Sophie and asked her to affirm in writing her late husband's promise to endow Hven to Tycho's heirs.

He realized that the young king was more interested in war than in science, and was of no mind to keep his father's promise. King Christian IV followed a policy of curbing the power of the nobility, by confiscating their estates to minimize their income bases, by accusing nobles of misusing their offices and of heresies against the Lutheran church. Tycho, who was known to sympathize with the Philippists

The Philippists formed a party in early Lutheranism. Their opponents were called Gnesio-Lutherans.

Before Luther's death

''Philippists'' was the designation usually applied in the latter half of the sixteenth century to the followers of Phi ...

, followers of Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, an intellectual leader of the L ...

, was among the nobles who fell out of grace with the new king. The king's unfavorable disposition towards Tycho was likely also a result of efforts by several of his enemies at court to turn the king against him.

In addition to Valkendorff, Tycho's enemies included the king's doctor Peter Severinus, who also had personal gripes with Tycho. Several gnesio-Lutheran Bishops suspected Tycho of heresya suspicion motivated by his known Philippist sympathies, his pursuits in medicine and alchemy, both of which he practiced without the church's approval, and his prohibiting the local priest on Hven to include the exorcism in the baptismal ritual. Among the accusations raised against Tycho were his failure to adequately maintain the royal chapel at Roskilde, and his harshness and exploitation of the Hven peasantry.

Tycho became even more inclined to leave when a mob of commoners, possibly incited by his enemies at court, rioted in front of his house in Copenhagen. Tycho left Hven in 1597, bringing some of his instruments with him to Copenhagen, and entrusting others to a caretaker on the island. Shortly before leaving, he completed his star catalogue giving the positions of 1,000 stars. After some unsuccessful attempts at influencing the king to let him return, including showcasing his instruments on the wall of the city, he acquiesced to exile. He wrote his most famous poem, ''Elegy to Dania'' in which he chided Denmark for not appreciating his genius.

The instruments he had used in Uraniborg and Stjerneborg were depicted and described in detail in his star catalogue

A star catalogue is an astronomical catalogue that lists stars. In astronomy, many stars are referred to simply by catalogue numbers. There are a great many different star catalogues which have been produced for different purposes over the year ...

or ''Instruments for the restoration of astronomy'', first published in 1598. The King sent two envoys to Hven to describe the instruments left behind by Tycho. Unversed in astronomy, the envoys reported to the king that the large mechanical contraptions such as his large quadrant and sextant were "useless and even harmful".

From 1597 to 1598, he spent a year at the castle of his friend Heinrich Rantzau

Heinrich Rantzau or Ranzow (Ranzovius) (11 March 1526 – 31 December 1598) was a German humanist writer and statesman, a prolific astrologer and an associate of Tycho Brahe. He was son of Johan Rantzau.

He was Governor of the Danish royal s ...

at Haus Wandesburg in Wandsbek

Wandsbek () is the second-largest of seven Boroughs and quarters of Hamburg#Boroughs, boroughs that make up the city and state of Hamburg, Germany. The name of the district is derived from the river Wandse which passes through here. Hamburg-Wandsb ...

outside Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

. Then they moved for a while to Wittenberg

Wittenberg, officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg, is the fourth-largest town in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, in the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. It is situated on the River Elbe, north of Leipzig and south-west of the reunified German ...

, where they stayed in the former home of Philip Melanchthon.

In 1599, he obtained the patronage of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg), Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–16 ...

and moved to Prague, as Imperial Court Astronomer. Tycho built a new observatory in a castle in Benátky nad Jizerou

Benátky nad Jizerou (; ) is a town in Mladá Boleslav District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 7,900 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected as an urban monument zone.

Administr ...

, 50 km from Prague, and worked there for one year. The emperor then brought him back to Prague, where he stayed until his death. At the imperial court even Tycho's wife and children were treated like nobility, which they had never been at the Danish court.

Tycho received financial support from several nobles in addition to the emperor, including Oldrich Desiderius Pruskowsky von Pruskow, to whom he dedicated his famous . In return for their support, Tycho's duties included preparing astrological chart

A horoscope (or other commonly used names for the horoscope in English include natal chart, astrological chart, astro-chart, celestial map, sky-map, star-chart, cosmogram, vitasphere, radical chart, radix, chart wheel or simply chart) is an astr ...

s and predictions for his patrons at events such as births, weather forecasting

Weather forecasting or weather prediction is the application of science and technology forecasting, to predict the conditions of the Earth's atmosphere, atmosphere for a given location and time. People have attempted to predict the weather info ...

, and astrological interpretations of significant astronomical events, such as the supernova of 1572, sometimes called Tycho's supernova, and the Great Comet of 1577.

Relationship with Kepler

In Prague, Tycho worked closely with Kepler, his assistant. Kepler was a convinced Copernican, and considered Tycho's model to be mistaken, and derived from simple "inversion" of the Sun's and Earth's positions in the Copernican model. Together, the two worked on a new star catalogue based on his own accurate positionsthis catalogue became the ''Rudolphine Tables

The ''Rudolphine Tables'' () consist of a star catalogue and planetary tables published by Johannes Kepler in 1627, using observational data collected by Tycho Brahe (1546–1601). The tables are named in memory of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emper ...

''. Also at the court in Prague was the mathematician Nicolaus Reimers (Ursus), with whom Tycho had previously corresponded, and who, like Tycho, had developed a geo-heliocentric planetary model, which Tycho considered to have been plagiarized from his own.

Kepler had previously spoken highly of Ursus, but now found himself in the problematic position of being employed by Tycho and having to defend his employer against Ursus' accusations, even though he disagreed with both of their planetary models. In 1600, he finished the tract (defense of Tycho against Ursus). Kepler had great respect for Tycho's methods and the accuracy of his observations and considered him to be the new Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; , ; BC) was a Ancient Greek astronomy, Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equinoxes. Hippar ...

, who would provide the foundation for a restoration of the science of astronomy.

Illness, death, and investigations

Tycho suddenly contracted a bladder or kidney ailment after attending a banquet in Prague. He died eleven days later, on 24 October 1601, at the age of 54. According to Kepler's first-hand account, Tycho had refused to leave the banquet to relieve himself because it would have been a breach of etiquette. After he returned home, he was no longer able to urinate, except eventually in very small quantities and with excruciating pain. The night before he died, he suffered from adelirium

Delirium (formerly acute confusional state, an ambiguous term that is now discouraged) is a specific state of acute confusion attributable to the direct physiological consequence of a medical condition, effects of a psychoactive substance, or ...

during which he was frequently heard to exclaim that he hoped he would not seem to have lived in vain.

Before dying, he urged Kepler to finish the ''Rudolphine Tables'' and expressed the hope that he would do so by adopting Tycho's own planetary system, rather than that of the polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

. It was reported that Tycho had written his own epitaph, "He lived like a sage and died like a fool." A contemporary physician attributed his death to a kidney stone

Kidney stone disease (known as nephrolithiasis, renal calculus disease, or urolithiasis) is a crystallopathy and occurs when there are too many minerals in the urine and not enough liquid or hydration. This imbalance causes tiny pieces of cr ...

, but no kidney stones were found during an autopsy

An autopsy (also referred to as post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of deat ...

performed after his body was exhumed in 1901. Modern medical assessment is that his death was more likely caused by either a burst bladder, prostatic hypertrophy

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also called prostate enlargement, is a noncancerous increase in size of the prostate gland. Symptoms may include frequent urination, trouble starting to urinate, weak stream, inability to urinate, or lo ...

, acute prostatitis

Prostatitis is an umbrella term for a variety of medical conditions that incorporate bacterial and non-bacterial origin illnesses in the pelvic region. In contrast with the plain meaning of the word (which means "inflammation of the prostate"), the ...

, or prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the neoplasm, uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Abnormal growth of the prostate tissue is usually detected through Screening (medicine), screening tests, ...

, which led to urinary retention

Urinary retention is an inability to completely empty the bladder. Onset can be sudden or gradual. When of sudden onset, symptoms include an inability to urinate and lower abdominal pain. When of gradual onset, symptoms may include urinary incont ...

, overflow incontinence

Overflow incontinence is a concept of urinary incontinence, characterized by the involuntary release of urine from an overfull urinary bladder, often in the absence of any urge to urinate. This condition occurs in people who have a blockage of the ...

, and uremia

Uremia is the condition of having high levels of urea in the blood. Urea is one of the primary components of urine. It can be defined as an excess in the blood of amino acid and protein metabolism end products, such as urea and creatinine, which ...

.

Investigations in the 1990s suggested that Tycho may not have died from urinary problems, but instead from mercury poisoning

Mercury poisoning is a type of metal poisoning due to exposure to mercury. Symptoms depend upon the type, dose, method, and duration of exposure. They may include muscle weakness, poor coordination, numbness in the hands and feet, skin rashe ...

. It was speculated that he had been intentionally poisoned. The two main suspects were his assistant, Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

, whose motives would be to gain access to Tycho's laboratory and chemicals, and his cousin, Erik Brahe, at the order of friend-turned-enemy Christian IV

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years and 330 days is the longest in Scandinavian history.

A member of the H ...

, because of rumors that Tycho had had an affair with Christian's mother.