The history of the Royal Australian Navy traces the development of the

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

(RAN) from the colonisation of Australia by the British in 1788. Until 1859, vessels of the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

made frequent trips to the new colonies. In 1859, the

Australia Squadron The Australian Squadron was the name given to the British naval force assigned to the Australia Station from 1859 to 1911.Dennis et al. 2008, p. 67.

The Squadron was initially a small force of Royal Navy warships based in Sydney, and although inten ...

was formed as a separate squadron and remained in Australia until 1913. Until

Federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

, five of the six Australian colonies operated their own colonial naval force, which formed on 1 March 1901 the Australian Navy's (AN) Commonwealth Naval Force which received Royal patronage in July 1911 and was from that time referred to as Royal Australian Navy (RAN). On 4 October 1913 the new replacement fleet for the foundation fleet of 1901 steamed through

Sydney Heads

The Sydney Heads (also simply known as the Heads) are a series of headlands that form the wide entrance to Sydney Harbour in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. North Head and Quarantine Head are to the north; South Head and Dunbar Head are to ...

for the first time.

The Royal Australian Navy has seen action in every ocean of the world. It first saw action in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, in the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans. Between the wars the RAN's fortunes shifted with the financial situation of Australia: it experienced great growth during the 1920s, but was forced to reduce its fleet and operations during the 1930s. Consequently, when it entered

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the RAN was smaller than it had been at the start of World War I. During the course of World War II, the RAN operated more than 350 fighting and support ships; a further 600 small civilian vessels were put into service as auxiliary patrol boats.

[ (Contrary to some claims, however, the RAN was not the fifth-largest navy in the world at any point during World War II.)

Following World War II, the RAN saw action in ]Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, and other smaller conflicts. Today, the RAN consists of a small but modern force, widely regarded as one of the most powerful forces in the Asia Pacific Region

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

.

Australia Station

In the years following the establishment of the British colony of New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

in 1788, Royal Navy ships of the East Indies Squadron under the command of the East Indies Station

The East Indies Station was a formation and command of the British Royal Navy. Created in 1744 by the Admiralty, it was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, East Indies.

Even in official documents, the term ''East Indies Station'' wa ...

would be station in or visit Australian waters. From the 1820s, a ship was sent annually to New South Wales, and occasionally to New Zealand.

In 1848, an Australian Division of the East Indies Station was established, and in 1859 the British Admiralty established an independent command, the Australia Station

The Australia Station was the British, and later Australian, naval command responsible for the waters around the Australian continent. Australia Station was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, Australia Station, whose rank varied over t ...

, under the command of a Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (India), in India

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ' ...

who was assigned as Commander-in-Chief, Australia Station.[Dennis et al. 2008, p.53.] The Australian Squadron The Australian Squadron was the name given to the British naval force assigned to the Australia Station from 1859 to 1911.Dennis et al. 2008, p. 67.

The Squadron was initially a small force of Royal Navy warships based in Sydney, and although inte ...

was created to which British naval ships serving on the Australia Station were assigned.Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

and New Zealand in particular.[ In 1884, the commander of the Australia Station was upgraded to the rank of ]rear admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

.[

At its establishment, the Australia Station encompassed Australia and New Zealand, with its eastern boundary including Samoa and Tonga, its western edge in the Indian Ocean, south of India and its southern edge defined by the ]Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. So ...

. The boundaries were modified in 1864, 1872 and 1893. At its largest, the Australia Station reached from the Equator to the Antarctic in its greatest north–south axis, and covered of the Southern Hemisphere in its extreme east–west dimension, including Papua New Guinea, New Zealand, Melanesia and Polynesia.

In 1911 the Australia Station passed to the Commonwealth Naval Forces (initially under the command of RN officers) and the Australian Squadron was disbanded. The Station, now under nominal Australian command, was reduced to only cover Australia and its island dependencies to the north and east. In 1911, the Commonwealth Naval Forces was renamed the Royal Australian Navy, which in 1913 came under Australian command. The Royal Navy's Australia Station's Sydney based depots, dockyards and structures were gifted to the Commonwealth of Australia. The Royal Navy continued to support the RAN and provided additional blue-water defence capability in the Pacific up to the early years of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Colonial navies and federation

Before the Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Wester ...

in 1901, five of the six self-governing colonies in Australia operated a navy, the exception being Western Australia which did not have a naval force. The colonial navies were supported by the ships of the Royal Navy's Australian Station which was established in 1859. In 1856, Victoria received its own naval vessel, HMCSS ''Victoria'', which in 1860 was deployed to assist the New Zealand colonial government during the First Taranaki War

The First Taranaki War (also known as the North Taranaki War) was an armed conflict over land ownership and sovereignty that took place between Māori people, Māori and the Colony of New Zealand in the Taranaki region of New Zealand's North Is ...

. When ''Victoria'' returned to Australia, the vessel had taken part in several minor actions, with the loss of one crew member. The deployment of ''Victoria'' to New Zealand marked the first occasion that an Australian warship had been deployed overseas. In the years leading up to Federation, Victoria had the most powerful of the colonial navies. Victoria had since 1870, as well as HMVS ''Nelson'', three small gunboats and five torpedo-boats. NSW had two very small torpedo boats, and the corvette ''Wolverine''. The colonial navies were expanded greatly in the mid-1880s and usually consisted of gunboats and torpedo-boats for coastal defence of harbours and rivers, and naval brigades to man vessels and forts.

On 1 January 1901, Australia became a federation of six States, as the Commonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and numerous smaller islands. It has a total area of , making it the sixth-largest country in ...

, which on 1 March 1901 took over the defence forces from the States, to form the Commonwealth Naval Forces

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond. The Chief of Navy is also jointly responsible to the Minister for D ...

. The Australian and New Zealand governments agreed with the Imperial government to help fund the Royal Navy's Australian Squadron, while the Admiralty committed itself to maintain the Squadron at a constant strength.vice admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of Vice ...

. The boundaries were again modified in 1908.

Formation

A growing number of people, among them Captain

A growing number of people, among them Captain William Rooke Creswell

Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Sir William Rooke Creswell, (20 July 1852 – 20 April 1933) was an Australian naval officer, commonly considered to be the 'father' of the Royal Australian Navy.

Early life and family

Creswell was b ...

, the director of the Commonwealth Naval Forces, demanded an autonomous Australian navy, financed and controlled by Australia. In 1907 Prime Minister Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister of Australia from 1903 to 1904, 1905 to 1908, and 1909 to 1910. He held office as the leader of th ...

and Creswell, while attending the Imperial Conference in London, sought the British Government's agreement to end the subsidy system and develop an Australian navy. The Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

rejected the idea, but suggested diplomatically that a small fleet of destroyers and submarines would be sufficient. Deakin was not impressed with the Admiralty, and in 1908 invited the United States Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the group of United States Navy battleships that completed a journey around the globe from 16 December 1907, to 22 February 1909, by order of President Foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt ...

to visit Australia. The visit prompted public enthusiasm for a modern navy and led to the order of two 700-ton s. The surge in German naval construction in 1909 led the Admiralty to change its position on an Australian navy, which resulted in the ''Naval Defence Act'' of 1910 being passed which created the Australian navy.

The first Australian warship, the destroyer , was launched at Govan

Govan ( ; Cumbric: ''Gwovan''; Scots language, Scots: ''Gouan''; Scottish Gaelic: ''Baile a' Ghobhainn'') is a district, parish, and former burgh now part of southwest Glasgow, Scotland. It is situated west of Glasgow city centre, on the sout ...

in Scotland on Wednesday 9 February 1910. Sister ship was launched at Dumbarton

Dumbarton (; , or ; or , meaning 'fort of the Britons (historical), Britons') is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, on the north bank of the River Clyde where the River Leven, Dunbartonshire, River Leven flows into the Clyde estuary. ...

in Scotland on Saturday 9 April 1910. Both ships were commissioned into the Royal Navy on 19 September 1910 and sailed for Australia, arriving at Port Phillip

Port Phillip (Kulin languages, Kulin: ''Narm-Narm'') or Port Phillip Bay is a horsehead-shaped bay#Types, enclosed bay on the central coast of southern Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia. The bay opens into the Bass Strait via a short, ...

on 10 December 1910. The event was marred by the death of Engineer Lieutenant W. Robertson, RN, who suffered a heart attack outside Port Phillip Heads whilst onboard HMAS ''Yarra'', and drowned.

The British Australia Station passed to the Commonwealth Naval Forces in 1911 and the Australian Squadron was disbanded. On 10 July 1911, King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

granted the title of "Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

" to the Commonwealth Naval Forces,His Majesty's Australian Ship

His Majesty's Australian Ship (HMAS) (or Her Majesty's Australian Ship when the monarch is female) is a ship prefix used for commissioned units of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). This prefix is derived from HMS (Her/His Majesty's Ship), the pr ...

"'' (HMAS). The Station was reduced to cover Australia and its island dependencies to the north and east, excluding New Zealand and its surrounds, which became part of the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China, was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 1 ...

and called the New Zealand Naval Forces.[ The Navy was to operate under the authority of the ]Australian Commonwealth Naval Board

The Australian Commonwealth Naval Board was the governing authority over the Royal Australian Navy from its inception and through World Wars I and II. The board was established on 1 March 1911 and consisted of civilian members of the Australian ...

, which functioned from 1 March 1911.

At the 1911 Imperial Conference Australia expressed concern about Japan's growing naval power and it was agreed that the British government would consult Australia when negotiating renewal of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The was an alliance between the United Kingdom and the Empire of Japan which was effective from 1902 to 1923. The treaty creating the alliance was signed at Lansdowne House in London on 30 January 1902 by British foreign secretary Lord Lans ...

.Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

. The RAN would become the Australia Squadron of the Royal Navy with all ships and personnel under the direct control of the British Admiralty, while the RAN remained responsible for the upkeep of the ships and training.

In 1913, responsibility for the reduced Australia Station passed to the new Royal Australian Navy[ under nominal Australian command, with the Australia Squadron of the Royal Navy's Australia Station coming to an end and its Sydney based depots, dockyards and structures being gifted to the Commonwealth of Australia. The first commanding officer was Admiral ]George Edwin Patey

Admiral Sir George Edwin Patey, (24 February 1859 – 5 February 1935) was a senior officer in the Royal Navy.

Early years

Patey was born on 24 February 1859 at Montpellier, near Plymouth, United Kingdom. His father, also named George Edwin Pat ...

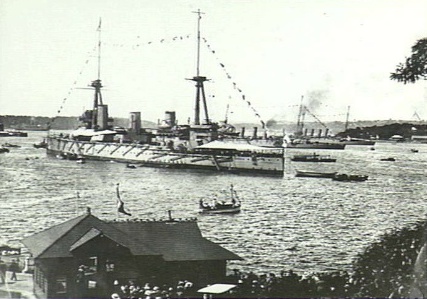

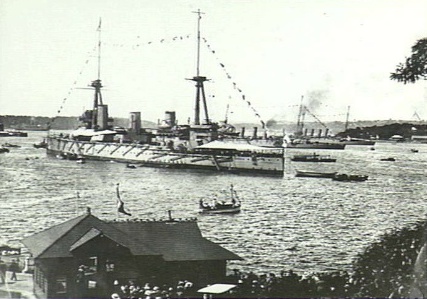

, Rear Admiral Commanding HM Australian Fleet, on loan from the Royal Navy. On Saturday 4 October 1913 the Australian fleet, consisting of the battle cruiser , the cruisers and , the protected cruiser , and the torpedo-boat destroyers ''Parramatta'', ''Yarra'' and , entered Sydney Harbour

Port Jackson, commonly known as Sydney Harbour, is a ria, natural harbour on the east coast of Australia, around which Sydney was built. It consists of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove River, Lane ...

for the first time.World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In 1958, the boundaries of Australia Station was redrawn again, now to include Papua New Guinea.[

]

World War I

On 3 August 1914, as the prospect of war with the

On 3 August 1914, as the prospect of war with the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

loomed, the Australian Government sent the following message to the Admiralty.

The United Kingdom declared war on Germany the next day, and on 8 August, the Australian Government received a reply, requesting that the transfer be made immediately, if not already done. Two days later, on 10 August, the Governor-General officially transferred control of the Royal Australian Navy to the British Admiralty, which would retain control until 19 August 1919.

At the outbreak of war, the RAN stood at 3,800 personnel and consisted of sixteen ships, including the battlecruiser ''Australia'', the light cruisers ''Sydney'' and ''Melbourne'', the destroyers ''Parramatta'', ''Yarra'', and ''Warrego'', and the submarines and . The light cruiser and three destroyers were under construction, and a small fleet of auxiliary ships was also being maintained. As a consequence the Royal Australian Navy at the start of the war was a small but formidable force.German New Guinea

German New Guinea () consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups, and was part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , became a German protectorate in 188 ...

by the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force

The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) was a small volunteer force of approximately 2,000 men, raised in Australia shortly after the outbreak of World War I to seize and destroy German wireless stations in German New Guin ...

(AN&MEF). Germany had colonised the northeastern part of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

and several nearby island groups in 1884, and the colony was currently used as a wireless radio base, Britain required the wireless installations to be destroyed because they were used by the German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron () was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. It was based at Germany's Ji ...

which threatened merchant shipping in the region. The objectives of the force were the German stations at Yap

Yap (, sometimes written as , or ) traditionally refers to an island group located in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, a part of Yap State. The name "Yap" in recent years has come to also refer to the state within the Federate ...

in the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the cen ...

, Nauru

Nauru, officially the Republic of Nauru, formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies within the Micronesia subregion of Oceania, with its nearest neighbour being Banaba (part of ...

, and Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in the province ...

in New Britain

New Britain () is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi Island, Umboi the Dampie ...

. On 30 August 1914, the AN&MEF left Sydney under the protection of ''Australia'' and ''Melbourne'' for Port Moresby

(; Tok Pisin: ''Pot Mosbi''), also referred to as Pom City or simply Moresby, is the capital and largest city of Papua New Guinea. It is one of the largest cities in the southwestern Pacific (along with Jayapura) outside of Australia and New ...

, where the force met the Queensland contingent, aboard the transport HMAHS ''Kanowna''. The force then sailed for German New Guinea on 7 September, leaving ''Kanowna'' behind when her stokers refused to work. ''Sydney'' and her escorting destroyers met the AN&MEF off the eastern tip of New Guinea. ''Melbourne'' was detached to destroy the wireless station on Nauru

Nauru, officially the Republic of Nauru, formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies within the Micronesia subregion of Oceania, with its nearest neighbour being Banaba (part of ...

, while on 14 September, ''Encounter'' bombarded a ridge near Rabaul, while half a battalion advanced towards the town. The only major loss of the campaign was the disappearance of the submarine ''AE1'' during a patrol off Rabaul on 14 September 1914.

On 9 November 1914, the German light cruiser attacked the Allied radio and telegraph station at Direction Island in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands (), officially the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (; ), are an Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean, comprising a small archipelago approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka and rel ...

. The inhabitants of the island managed to transmit a distress signal, which was received by ''Sydney'', only away. ''Sydney'' arrived within two hours, and was engaged by ''Emden''. ''Sydney'' was the larger, faster and better armed of the two, and eventually overpowered ''Emden'', with captain Karl von Müller running the ship aground on North Keeling Island

North Keeling is a small, uninhabited coral atoll, approximately in area, about north of Horsburgh Island. It is the northernmost atoll and island of the Australian territory of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Cocos (Keeling) Islan ...

at 11:15 am. At first, ''Emden'' refused to strike its colours and surrender; ''Sydney'' fired on the stationary ''Emden'' until it eventually struck its colours. The Battle of Cocos

The Battle of Cocos was a single-ship action that occurred on 9 November 1914, after the Australian light cruiser , under the command of John Glossop, responded to an attack on a communications station at Direction Island by the German light c ...

was the first battle the RAN participated in.Battle of Rufiji Delta

The Battle of the Rufiji Delta was fought in German East Africa (modern Tanzania) from October 1914–July 1915 during the First World War, between the German Navy's light cruiser , and a powerful group of British warships. The battle was a seri ...

. ''Pioneer'' remained off East Africa and took part in many bombardments of German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

, including Dar-es-Salaam

Dar es Salaam (, ; from ) is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over 7 million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa by population and the ...

on 13 June 1916. ''Pioneer'' then returned to Australia, to be decommissioned in October 1916.

During the Naval operations in the Dardanelles Campaign the Australian submarine became the first Allied warship to breach the Turkish defences of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

. ''AE2'' spent five days in the area, was unsuccessfully attacked several times, but was unable to find any large enemy troop transports. On 29 April 1915, she was damaged in an attack by the Turkish torpedo-boat ''Sultan Hisar'' in Artaki Bay and was scuttled by her crew. The wreck of ''AE2'' remained undiscovered until June 1998.Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in the blockade of the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect of the fleet; ...

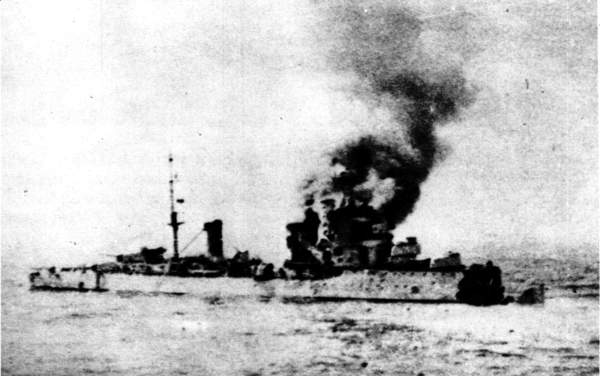

. In February 1915, HMAS ''Australia'' joined the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from th ...

, and was made flagship of the 2nd Battle Cruiser Squadron.Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

; in April, the battlecruiser was damaged in a collision with sister ship , and she did not return to service until June.[Jose, ''The Royal Australian Navy 1914–1918'', p. 274] Three RAN ships were present during the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect of the fleet; ...

; ''Australia'', ''Sydney'', and ''Melbourne'', with ''Australia'' leading the port division of the Grand Fleet as it sailed out to meet the Germans.[Stevens, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', pp. 52–3]

The most decorated Australian Naval unit of World War One, however was not a ship at all, but the Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train

The Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train was a unique unit of the Royal Australian Navy. It was active only during the First World War, where it served in the Gallipoli and the Sinai and Palestine Campaigns. The Train was formed in February 1915 ...

, a land-based unit composed mostly of reservists which landed at Suvla Bay with the British IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German ...

and was responsible for receiving, storing and distributing the supplies, including potable water, of the British troops at Suvla.Battle of Magdhaba

The Battle of Magdhaba took place on 23 December 1916 during the Defence of Egypt section of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in the First World War.The Battles Nomenclature Committee assigned 'Affair' to those engagements between forces smalle ...

, before returning to Australia and being disbanded after a series of miscommunications during May 1917.

Expansion during the war had been limited, with the RAN growing to include thirty-seven ships and more than 5,000 personnel by 1918. The RAN's losses had also been modest, only losing the two submarines ''AE1'' and ''AE2'', whilst casualties included 171 fatalities – 108 Australians and 63 officers and men on loan from the Royal Navy, with less than a third the result of enemy action.

The 1918–19 influenza pandemic

Between April 1918 and May 1919, the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest docum ...

killed approximately 25 million people worldwide, far more than had been killed in four years of war. A rigorous quarantine policy was implemented in Australia; although this reduced the immediate impact of the flu, the nation's death toll surpassed 11,500.British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

in 1918; the Australian cruisers assigned to the fleet suffered high casualties, with up to 157 casualties in one ship alone. Outbreaks in the Mediterranean fleets were more severe than those in the Atlantic. recorded 183 casualties between November and December 1918, of those casualties 2 men died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

. The RAN lost a total of 26 men to the disease; further loss prevented primarily by the ready availability of professional medical treatment.

South Pacific aid mission

The disease arrived in the South Pacific on the cargo vessel , which sailed from

The disease arrived in the South Pacific on the cargo vessel , which sailed from Auckland

Auckland ( ; ) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. It has an urban population of about It is located in the greater Auckland Region, the area governed by Auckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and ...

on 30 October 1918 whilst knowingly carrying sick passengers. ''Talune'' stopped in Fiji

Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islands—of which about ...

, Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

, Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

and Nauru

Nauru, officially the Republic of Nauru, formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies within the Micronesia subregion of Oceania, with its nearest neighbour being Banaba (part of ...

: the first outbreaks in these locations occurred within days of the ships visits. The local authorities were generally unprepared for the size of the outbreak, allowing the infection to spread uncontrollably. The German territory of Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

was the worst affected of the small islands, the New Zealand administration carried out no efforts to lessen the outbreak and rejected offers of assistance from nearby American Samoa

American Samoa is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States located in the Polynesia region of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. Centered on , it is southeast of the island count ...

. The New Zealand government officially apologised to Samoa in 2002 for their reaction to the outbreak. On 29 November 1918 the military governor of Apia

Apia () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city of Samoa. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

The Apia Urban A ...

requested assistance from Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

; the request was turned down because all doctors were needed in New Zealand. Australia offered the only alternate source of aid.

The Commonwealth Naval Board was aware of the worsening situation in the region; the sloop reported its first case on 11 November 1918 while stationed in Fiji, with half her complement eventually affected. On 20 November 1918, the Naval Board began forming a joint relief expedition from available military medical personnel. The commanding officer of was then ordered to embark the expedition in Sydney and sail as soon as possible. ''Encounter'' departed Sydney on 24 November 1918, ten minutes after completing loading.Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia located at the mouth of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australi ...

and the captain did not want a repeat. ''Encounter'' arrived in Suva

Suva (, ) is the Capital city, capital and the most populous city of Fiji. It is the home of the country's largest metropolitan area and serves as its major port. The city is located on the southeast coast of the island of Viti Levu, in Rew ...

on 30 November and took on half of the available coal and 39 tonnes of water. Spanish flu was rampant in Suva; Captain Thring implemented a strict quarantine, placed guards on the wharf, and ordered that coaling be carried out by the crew instead of native labour. ''Encounter'' departed Suva in the evening of the same day and arrived off Apia

Apia () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city of Samoa. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

The Apia Urban A ...

on 3 December. Within six hours, the medical landing party assigned to Apia and their stores were ashore. ''Encounter'' then departed for the Tongan capital of Nukualofa, arriving on 5 December. The last of the medical staff and supplies were unloaded, and ''Encounter'' sailed for Suva on 7 December to re-coal. On arriving in Suva, ''Encounter'' received orders to return to Sydney, where reached on 17 December and was immediately placed into quarantine. The South Pacific aid mission is regarded as Australia's first overseas relief expedition, and set a precedent for future relief missions conducted by the RAN.

Between the Wars

Following the end of

Following the end of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Australian Government

The Australian Government, also known as the Commonwealth Government or simply as the federal government, is the national executive government of Australia, a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy. The executive consists of the pr ...

believed that an immediate evaluation of the RAN was necessary. Australia had based its naval policy on the Henderson ''Recommendations'' of 1911, developed by Sir Reginald Henderson. The government sent an invitation to Admiral John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland ...

, he arrived in Australia in May 1919. Jellicoe remained in Australia for three months, before returning to England via New Zealand and Canada. Jellicoe submitted his findings in August 1919, titled the ''Report on the Naval Mission to the Commonwealth''. The report outlined several policies designed to strengthen British naval strength in the Pacific Ocean. The report heavily stressed a close relationship between the RAN and the Royal Navy. This would be achieved by strict adherence to the procedures and administration methods of the Royal Navy. The report also suggested constant officer exchange between the two forces. Jellicoe also called for the creation of a large Far East Imperial Fleet, which would be based in Singapore and include capital ships and aircraft carriers. The creation cost for this fleet was to be divided between Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand: contributing 75%, 20%, and 5% respectively. The suggested makeup of the RAN would include; one aircraft carrier, two battlecruisers, eight light cruisers, one flotilla leader, twelve destroyers, a destroyer depot ship, eight submarines, one submarine depot ship, and a small number of additional auxiliary ships. The annual cost and depreciation of the fleet was estimated to be £4,024,600. Except for implementing closer ties with the Royal Navy, none of Jellicoe's major recommendations were carried out.[Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Volume I – Royal Australian Navy, 1939 – 1942 (1st edition, 1957) Chapter 1 Accessed 3 September 2006](_blank)

With the end of World War I, the Australian Government began to worry about the threat Japan posed to Australia. Japan had extended its empire to the south, bringing it right to Australia's doorstep. Japan had continued to build up its naval force, and had reached the point where it outgunned the Royal Navy in the Pacific. The RAN and the government believed that the possibility of a Japanese invasion was highly likely. In his report, Admiral Jellicoe believed that the threat of a Japanese invasion of Australia would remain as long as the White Australia Policy remained in place. Due to the perceived threat, and bilateral support in Australia for the White Australia Policy, the Australian Government became a vocal supporter of the continuance of the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance. Australia was joined in its support for the alliance by New Zealand but was heavily opposed by Canada, which believed that the alliance had hindered the British Empire's relationship with China and the United States. No decision on the alliance was agreed on, and the discussion was shelved pending the outcome of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

. The results of the treaty, which allowed the British to retain naval supremacy in the Pacific Ocean, created a sense of security in Australia. Many Australians saw the Four Powers Pact as replacing the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. This sense of security became known as the ''Ten Year Rule''. This led to defence retrenchments in Australia, following the international trend, and a £500,000 reduction in expenditure. The Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

Henry Forster

Henry William Forster, 1st Baron Forster, (31 January 1866 – 15 January 1936) was a British politician who served as the seventh Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1920 to 1925. He had previously been a government minister under ...

when opening parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

on 22 June 1922 was quoted as saying: Between World War I and

Between World War I and World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

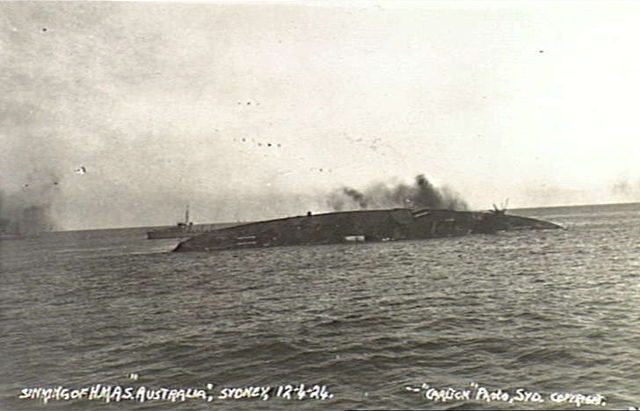

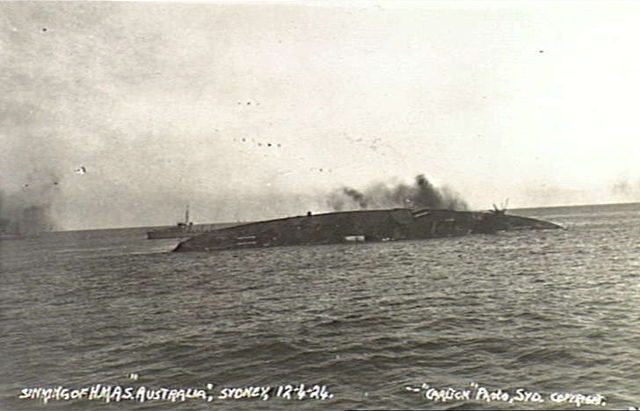

, the Royal Australian Navy underwent a severe reduction in ships and manpower. As a result of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

, the flagship HMAS ''Australia'' was scrapped with her main armaments and sunk outside Sydney Heads

The Sydney Heads (also simply known as the Heads) are a series of headlands that form the wide entrance to Sydney Harbour in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. North Head and Quarantine Head are to the north; South Head and Dunbar Head are to ...

in 1924.Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

of 1929 led to another reduction of manpower; although reduced in size, the available posts were easily filled as many men were unemployed and the offered pay was greater than most jobs. The RAN's personnel strength fell to 3,117 personnel, plus 131 members of the Naval Auxiliary Services. By 1932, the strength of the Reserves stood at 5,446. In the early 1930s, lack of funds forced the transfer of the Royal Australian Naval College

HMAS Creswell is a training facility of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) that includes the Royal Australian Naval College (RANC) as well as the School of Survivability and Ship's Safety, Beecroft Weapons Range, and an administrative support depa ...

from Jervis Bay

Jervis Bay () is a oceanic bay and village in the Jervis Bay Territory and on the South Coast (New South Wales), South Coast of New South Wales, Australia.

A area of land around the southern headland of the bay, known as the Jervis Bay Terri ...

to Flinders Naval Depot

HMAS ''Cerberus'' is a Royal Australian Navy (RAN) base that serves as the primary training establishment for RAN personnel. The base is located adjacent to Crib Point on the Mornington Peninsula, south of the Melbourne City Centre, Victor ...

in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

. In 1933 the Australian Government ordered three light cruisers; HMA Ships , , and ; selling the seaplane carrier ''Albatross'' to fund ''Hobart''. During this time, the RAN also purchased destroyers of the V and W destroyer classes, the ships that would become known as the Scrap Iron Flotilla

The Scrap Iron Flotilla was an Australian destroyer group that operated in the Mediterranean and Pacific during World War II. The name was bestowed upon the group by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.

The flotilla consisted of five Royal ...

. With the ever-increasing threat of Germany and Japan in the late 1930s, the RAN was not in the position it was at the outbreak of World War I.

World War II

Australia declared war on Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

one hour after the United Kingdom's declaration of war on 3 September 1939. Unlike the arrangements with the British Admiralty at the start of the First World War, during World War II RAN ships remained under Australian command.

At the onset of war the RAN was relatively modest, even if it was arguably the most combat-ready of the three services. Major units included:

* two County-class heavy cruisers; and , both carried guns and had entered service in the 1920s

* three modern Modified Leander-class light cruisers; , , and , which mounted guns

* the older Town-class cruiser

* four sloops, , , , and ; although only ''Swan'' and ''Yarra'' were in commission

* five V-class destroyers

* a variety of support and ancillary craft

Following the call up of reserves in 1939 the permanent forces grew from 5,440 to 10,259.

During the war the men and vessels of the RAN served in every theatre of operations, from the tropical Pacific to the frigid Russian convoys and grew exponentially. The table illustrates the growth of the RAN between the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939 and 30 June 1945.

Operations against Italy, Vichy France and Germany

From mid-1940, ships of the RAN, at the request of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

, began to deploy to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

to take part in the Battle of the Mediterranean

The Battle of the Mediterranean was the name given to the naval campaign fought in the Mediterranean Sea during World War II, from 10 June 1940 to 2 May 1945.

For the most part, the campaign was fought between the Kingdom of Italy, Italian Reg ...

against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

. In September 1939, the Admiralty and the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board agreed to deploy the RAN Destroyer Flotilla outside the Australia Station

The Australia Station was the British, and later Australian, naval command responsible for the waters around the Australian continent. Australia Station was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, Australia Station, whose rank varied over t ...

; the five ships of what was to become known as the Scrap Iron Flotilla

The Scrap Iron Flotilla was an Australian destroyer group that operated in the Mediterranean and Pacific during World War II. The name was bestowed upon the group by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.

The flotilla consisted of five Royal ...

arrived at Malta in mid-December. HMAS ''Sydney'' deployed in May 1940 and was later joined by ''Hobart''. When Italy declared war on 10 June 1940, the Australian warships made up five of the twenty-two Allied destroyers and one of the five modern light cruisers on station in the Mediterranean. The RAN then offered the services of ''Australia'' to the Admiralty, and was accepted. When ''Australia'' arrived in the Mediterranean, the RAN had sent nearly the entire combat fleet to the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

, leaving Australia open to possible attack.

The entry of Italy into the war also lead to a far more active role for the few remaining RAN vessels on the Australian Station. Indeed, on 12 June 1940, after a prolonged chase, the Armed Merchant Cruiser (AMC) forced the Italian merchant ship ''Romolo'' (9,780 tons) to scuttle south-west of Nauru

Nauru, officially the Republic of Nauru, formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies within the Micronesia subregion of Oceania, with its nearest neighbour being Banaba (part of ...

.

On 27 June 1940, Admiral Cunningham

Cunningham is a surname of Scottish origin, see Clan Cunningham.

Notable people sharing this surname

A–C

*Aaron Cunningham (born 1986), American baseball player

* Abe Cunningham, American drummer

*Adrian Cunningham (born 1960), Australian ...

commander of the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

ordered the 7th Cruiser Squadron, which included HMAS ''Sydney'', to rendezvous with an Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

-bound convoy near Cape Matapan

Cape Matapan (, Maniot dialect: Ματαπά), also called Cape Tainaron or Taenarum (), or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matapan is the southernmost point of mainland Greece, and the second southe ...

.[Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', p. 165] Within an hour, the was incapacitated and ''Sydney'' was signalled to sink her.[ As ''Sydney'' approached, ''Espero'' launched torpedoes, but failed to hit any targets.][ ''Sydney'' fired four salvos, scoring ten direct hits on ''Espero''.][ ''Sydney'' remained at the scene for two hours picking up survivors.][

Also on 27 June 1940, the was scuttled south of ]Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

after being depth-charged by and the British destroyers , , , and . On 29 June 1940, another Italian submarine, the , was sunk west of Crete by the same ships.

On 7 July 1940, a 25-ship fleet departed Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, intending to meet a convoy east of Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

.[Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', pp. 172–3] The next day, a submarine sighted an Italian fleet away; the Allied fleet altered course to intercept.[Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', p. 173] The two fleets sighted each other at 15.00 on 9 July 1940, and a battle that became known as the Battle of Calabria

The Battle of Calabria (9 July 1940) known to the Italian Navy as the Battle of Punta Stilo, was a naval battle during the Battle of the Mediterranean in the Second World War. Ships of the were opposed by vessels of the Mediterranean Fleet. ...

began.[Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', p. 176] Four vessels of the RAN took part in the battle; HMA Ships ''Sydney'', , , and ''Voyager''. ''Sydney'' was the first RAN vessel to engage the enemy, and at 15.20 opened fire on an Italian cruiser.[ When the Italian fleet began to withdraw, the Allied destroyer squadron was ordered forward. ''Stuart'', leading the destroyer force, was the first to open fire; her opening salvo was a direct hit at a range of . Both fleets retired, with the Italians withdrawing under smoke, but Italian aircraft continued to attack Allied ships.][Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', p. 177] ''Sydney'', which came under heavy air attack, was believed to have sunk. The fleet arrived back in Alexandria on 13 July.[

] On 17 July 1940, HMAS ''Sydney'' and the destroyer were ordered to support a

On 17 July 1940, HMAS ''Sydney'' and the destroyer were ordered to support a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

destroyer squadron on a sweep north of the island of Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

.[Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', p. 184] At 07.20 on 19 July, the Italian cruisers and , which opened fire seven minutes later.[Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', pp. 185–6] The four British destroyers retreated to the north-east, while ''Sydney'' and ''Havock'', away, began to close in. ''Sydney'' sighted the cruisers at 08.29, and fired the first shots of the Battle of Cape Spada

The Battle of Cape Spada was a naval battle between the Royal Navy and the during the Battle of the Mediterranean in the second World War. It took place on 19 July 1940 in the Mediterranean Sea off Cape Spada, the north-western extremity of Cr ...

at a range of .[Macdougall 1991, p. 181.] Within minutes, ''Sydney'' had successfully damaged ''Bande Nere'', and when the Italians withdrew to the south, the six Allied ships pursued. At 0848, with ''Bande Nere'' hiding behind a smoke screen, ''Sydney'' shifted her fire to ''Bartolomeo Colleoni'', which was disabled by 0933.[Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 150] The Australian cruiser left to pursue ''Bande Nere'', but broke off at 10.27 as the Italian warship was out of range, and ''Sydney'' was dangerously low on ammunition. On 30 September 1940, HMAS ''Stuart'' destroyed the Italian 600-Serie Adua class submarine ''Gondar'', killing two of its crew. Twenty-eight survivors was subsequently rescued by ''Stuart'', with a further nineteen picked up by other vessels.

On 27 March 1941, an Allied fleet under Admiral

On 30 September 1940, HMAS ''Stuart'' destroyed the Italian 600-Serie Adua class submarine ''Gondar'', killing two of its crew. Twenty-eight survivors was subsequently rescued by ''Stuart'', with a further nineteen picked up by other vessels.

On 27 March 1941, an Allied fleet under Admiral Cunningham

Cunningham is a surname of Scottish origin, see Clan Cunningham.

Notable people sharing this surname

A–C

*Aaron Cunningham (born 1986), American baseball player

* Abe Cunningham, American drummer

*Adrian Cunningham (born 1960), Australian ...

was ambushed by an Italian naval force off Cape Matapan

Cape Matapan (, Maniot dialect: Ματαπά), also called Cape Tainaron or Taenarum (), or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matapan is the southernmost point of mainland Greece, and the second southe ...

, Greece. Three vessels of the RAN took part in the battle; HMA Ships ''Perth'', ''Stuart'', and ''Vampire''. The victory at Cape Matapan allowed the evacuation of thousands of Allied troops from Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

.

was torpedoed and sunk on 27 November 1941 by whilst escorting transports resupplying the Allied garrison at Tobruk

Tobruk ( ; ; ) is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near the border with Egypt. It is the capital of the Butnan District (formerly Tobruk District) and has a population of 120,000 (2011 est.)."Tobruk" (history), ''Encyclop� ...

. There were 24 survivors, but 138 men, including all officers, lost their lives.

The Australians experienced further success on 15 December 1941 when attacked and sank the German submarine off Cape St. Vincent, Portugal.[Stevens 2001, p. 151.]

West Africa

On 6 September 1940, HMAS ''Australia'' was ordered to sail to Freetown

Freetown () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, e ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

to join Operation Menace

The Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 by the Allies to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern-day Senegal). It was hoped that the success of the operation cou ...

, the invasion of Vichy French

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against G ...

-controlled Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

in French West Africa

French West Africa (, ) was a federation of eight French colonial empires#Second French colonial empire, French colonial territories in West Africa: Colonial Mauritania, Mauritania, French Senegal, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guin ...

. On 19 September, ''Australia'' and the cruiser sighted three Vichy cruisers heading south and shadowed them. When the French cruiser ''Gloire'' developed engine trouble, ''Australia'' escorted her towards Casablanca

Casablanca (, ) is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business centre. Located on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a populatio ...

and returned to the fleet two days later. On 23 September ''Australia'' came under heavy fire from shore batteries, then drove two Vichy destroyers back into port. ''Australia'' then engaged and sunk the destroyer ''L'Audacieux'' with eight salvos in sixteen minutes. Over the next two days French and Allied forces exchanged fire; ''Australia'' was struck twice and lost her Walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large pinniped marine mammal with discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. It is the only extant species in the family Odobeni ...

amphibian. ''Australia'' and the rest of the fleet retired on 25 September the battle became known as the Battle of Dakar

The Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 by the Allies of World War II, Allies to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern-day Senegal). It was hoped that the succ ...

.

The "Scrap-Iron Flotilla"

The Scrap Iron Flotilla

The Scrap Iron Flotilla was an Australian destroyer group that operated in the Mediterranean and Pacific during World War II. The name was bestowed upon the group by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.

The flotilla consisted of five Royal ...

was an Australian destroyer group that operated in the Mediterranean and Pacific during World War II. The name was bestowed upon the group by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and philologist who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief Propaganda in Nazi Germany, propagandist for the Nazi Party, and ...

who described the fleet as a ''"consignment of junk"'' and ''"Australia's Scrap-Iron Flotilla"''. The flotilla consisted of five vessels; , which acted as flotilla leader, and four V-class destroyers; , , , . The ships were all built to fight in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and were slow and poorly armed compared to newer ships.[Macdougall 1991, p. 216.] The five destroyers—the entirety of the RAN's destroyer force—departed Australia in November 1939 destined for Singapore where they carried out anti-submarine exercises with the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

submarine . On 13 November 1939, the flotilla left Singapore for the Mediterranean Sea, following a request from the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

for assistance.

The Australian destroyer flotilla took part in multiple actions while in the Mediterranean, including the Allied evacuation following the battle of Greece in April 1941, though the flotilla came to fame in the mission to resupply the besieged city of Tobruk. The resupply routes from Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

and Mersa Matruh

Mersa Matruh (), also transliterated as Marsa Matruh ( Standard Arabic ''Marsā Maṭrūḥ'', ), is a port in Egypt and the capital of Matrouh Governorate. It is located west of Alexandria and east of Sallum on the main highway from the Nile ...

to Tobruk

Tobruk ( ; ; ) is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near the border with Egypt. It is the capital of the Butnan District (formerly Tobruk District) and has a population of 120,000 (2011 est.)."Tobruk" (history), ''Encyclop� ...

became known as ''"Bomb Alley"'' and was subject to constant Axis air attacks.

Red Sea

As well as serving in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

, ships of the RAN also served in the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. In August 1940, Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

forces invaded British Somaliland. After a fighting withdrawal, the small British garrison was evacuated from Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

, with assisting in the destruction of the port and its facilities. To aid in the delaying action, ''Hobart'' sent a 3-pounder gun ashore, operated by volunteers from the crew. The seamen were captured by the Italians, but were later liberated. Two RAN sloops joined the Red Sea force in 1940: ''Parramatta'' on 30 July and ''Yarra'' in September. In October, ''Yarra'' engaged and drove off two Italian destroyers attempting to raid a convoy. Although vessels of the RAN served in the Red Sea throughout the war, after 1941 the larger RAN ships were deployed to Australian waters in response to the threat from Japan.

Loss of HMAS ''Sydney''

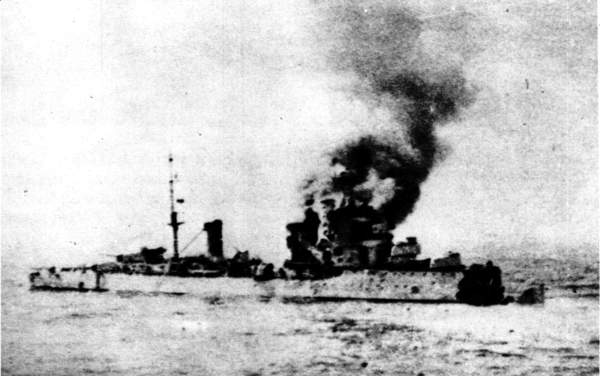

On 19 November 1941, the Australian light cruiser and the German auxiliary cruiser engaged each other in the Indian Ocean, off

On 19 November 1941, the Australian light cruiser and the German auxiliary cruiser engaged each other in the Indian Ocean, off Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

. The two ships sank each other: ''Sydney'' was lost with all 645 hands, while the majority of the ''Kormoran''s crew were rescued and became prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

. The location of both wrecks remained a mystery to many and subject to much controversy until 16–17 March 2008, when both ships were found.

North Africa

RAN units continued to serve in the Mediterranean campaign, with , taking part in Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, the invasion of North Africa. On 28 November 1942 Quiberon assisted in sinking the Italian submarine Dessiè and three days later also took part in the destruction of a four-ship convoy and a destroyer.

Sicily 1943

During early 1943, eight Australian-designed and built s were transferred to Egypt from the Indian Ocean, in preparation for Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

.

War with Japan

After the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

's attacks on the Allies in December 1941, the RAN redeployed its larger ships to home waters to protect the Australian mainland from Japanese attack, while several smaller ships remained in the Mediterranean. From 1940 onwards, there was considerable Axis naval activity in Australian waters

There was considerable Axis naval activity in Australian waters during the Second World War, despite Australia being remote from the main battlefronts. German and Japanese warships and submarines entered Australian waters between 1940 and 194 ...

first from German commerce raiders and submarines and later by the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

.

Initially, RAN ships served as part of the British-Australian component of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, or ABDACOM, was the short-lived supreme command for all Allied forces in South East Asia in early 1942, during the Pacific War in World War II. The command consisted of the forces of Austra ...

(ABDACOM) naval forces or in the ANZAC Force

The ANZAC Squadron, also called the ''Allied Naval Squadron'', was an Allied naval warship task force that was tasked with defending northeast Australia and surrounding area in early 1942 during the Pacific Campaign of World War II. The squadron ...

. ABDACOM was wound up following the fall of the Netherlands East Indies and was succeeded by the South West Pacific Area (command)

South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, th ...

(SWPA). The United States Seventh Fleet

The Seventh Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy. It is headquartered at U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. It is part of the United States Pacific Fleet. At present, it is the largest of the ...

was formed at Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

on 15 March 1943, for service in the SWPA. RAN ships in the Pacific generally served at part of Seventh Fleet taskforces.

Timor

From February 1942, the RAN played a critical role in resupplying Australian and Dutch commandos on Timor. ''Voyager'' was not the only loss during the campaign. On 1 December 1942, was attacked by thirteen Japanese aircraft while attempting to land Dutch soldiers off Betano, Portuguese Timor

Portuguese Timor () was a Portuguese colony on the territory of present-day East Timor from 1702 until 1975. During most of this period, Portugal shared the island of Timor with the Dutch East Indies.

The first Europeans to arrive in the regio ...

. ''Armidale'' sank with the loss of 40 of her crew and 60 Dutch personnel. During the engagement, Ordinary Seaman Teddy Sheean

Edward "Teddy" Sheean, (28 December 1923 – 1 December 1942) was a sailor in the Royal Australian Navy during the Second World War. Born in Tasmania, Sheean was employed as a farm labourer when he enlisted in the Royal Australian Naval Reserve ...

operated an Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun and was wounded by strafing Japanese planes, he went down with the ship, still strapped into the gun and still shooting at the attacking aircraft.

Java Sea

On 28 February 1942, a joint ABDA naval force met a Japanese invasion force in the Java Sea

The Java Sea (, ) is an extensive shallow sea on the Sunda Shelf, between the Indonesian islands of Borneo to the north, Java to the south, Sumatra to the west, and Sulawesi to the east. Karimata Strait to its northwest links it to the South Ch ...

. The ''Leander''-class cruiser and the American heavy cruiser fought in and survived the Battle of the Java Sea

The Battle of the Java Sea (, ) was a decisive naval battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II.

Allied navies suffered a disastrous defeat at the hand of the Imperial Japanese Navy on 27 February 1942 and in secondary actions over succ ...

.

On 1 March 1942, the ''Perth'' and ''Houston'' attempted to move through the Sunda Strait to Tjilatjap

Cilacap Regency (, also spelt: Chilachap, old spelling: Tjilatjap, Sundanese: ) is a regency () in the southwestern part of Central Java province in Indonesia. Its capital is the town of Cilacap, which had 263,098 inhabitants in mid 2024, sprea ...

however they found their path blocked by the main Japanese invasion fleet from western Java. The Allied ships were engaged by at least three cruisers and several destroyers and in a ferocious night action, known as the Battle of Sunda Strait

The Battle of Sunda Strait was a naval battle which occurred during World War II in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java, and Sumatra. On the night of 28 February 1 March 1942, the Australian light cruiser , American heavy cruiser , ...

, both Perth and Houston were torpedoed and sunk. Casualties aboard ''Perth'' included 350 crew and 3 civilians killed, while 324 survived the sinking and were taken prisoner by the Japanese (106 of whom later died in captivity). The loss of ''Perth'' so soon after the sinking of her sister ''Sydney'', had a major psychological effect on the Australian people. Japanese losses included a minesweeper and a troop transport sunk by friendly fire, whilst three other transports were damaged and had to be beached.

Coral Sea

On 2 May 1942, two ships of the RAN were part of the Allied force in the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea, from 4 to 8 May 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and naval and air forces of the United States and Australia. Taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, the battle ...

; HMA Ships and as part of Task Force 44

Task Force 44 was an Allied naval task force during the Pacific Campaign of World War II. The task force consisted of warships from the United States Navy and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). It was generally assigned as a striking force to d ...

. Both ships came under intense air attack, while part of a force guarding the approaches to Port Moresby