Transcarpathia (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Transcarpathia is a historical region on the border between

Carpathian Ruthenia rests on the southern slopes of the eastern

Carpathian Ruthenia rests on the southern slopes of the eastern

In 1526 the region was divided between the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary and the

In 1526 the region was divided between the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary and the

Throughout November and the following few months, councils met every few weeks, calling for various solutions. Some wanted to remain part of the Hungarian Democratic Republic, but with greater autonomy; the most notable of these, the

In November 1938, under the

In November 1938, under the

Memoirs and historical studies provide much evidence that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Rusyn-Jewish relations were generally peaceful. In 1939, census records showed that 80,000 Jews lived in the autonomous province of Ruthenia. Jews made up approximately 14% of the prewar population; however, this population was concentrated in the larger towns, especially

The Soviet takeover of the region started with the East Carpathian Strategic Offensive in the fall of 1944. This offensive consisted of two parts: the

The Soviet takeover of the region started with the East Carpathian Strategic Offensive in the fall of 1944. This offensive consisted of two parts: the

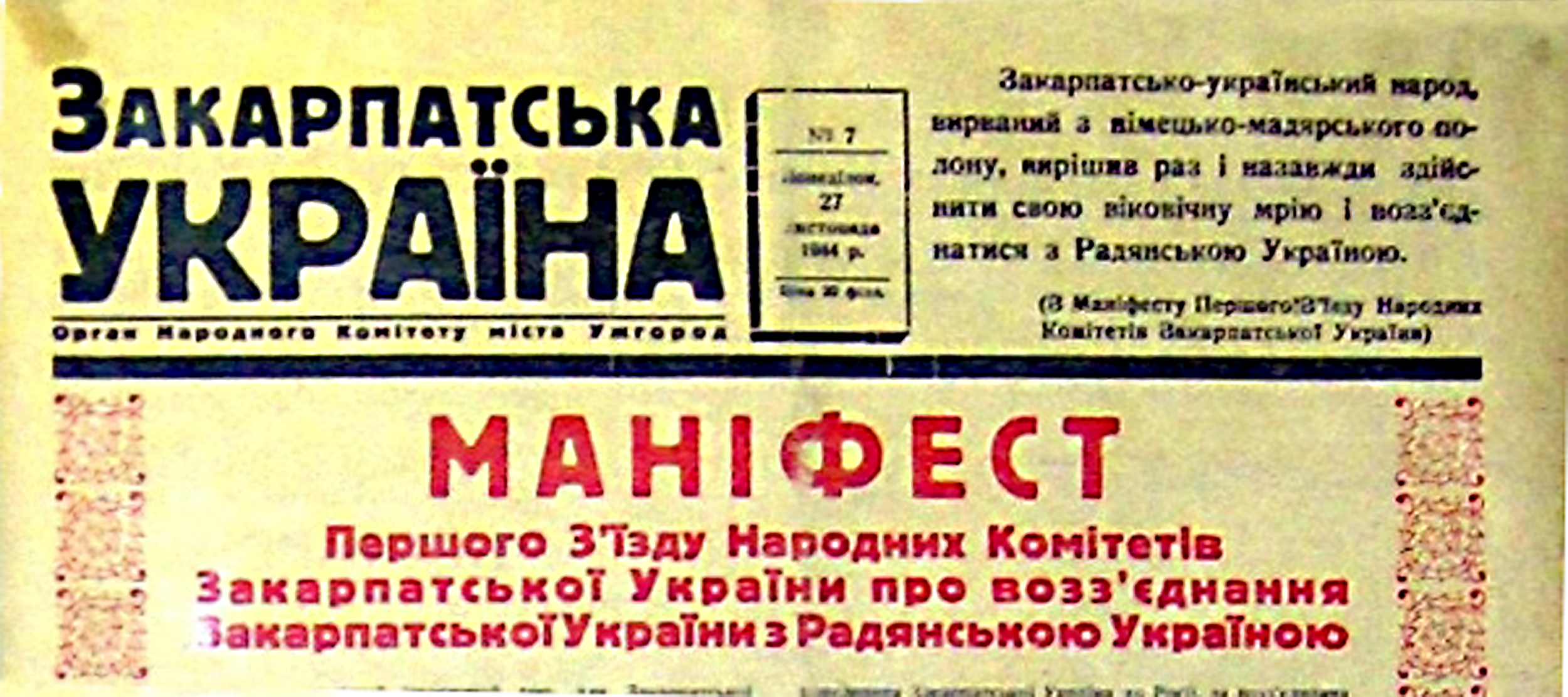

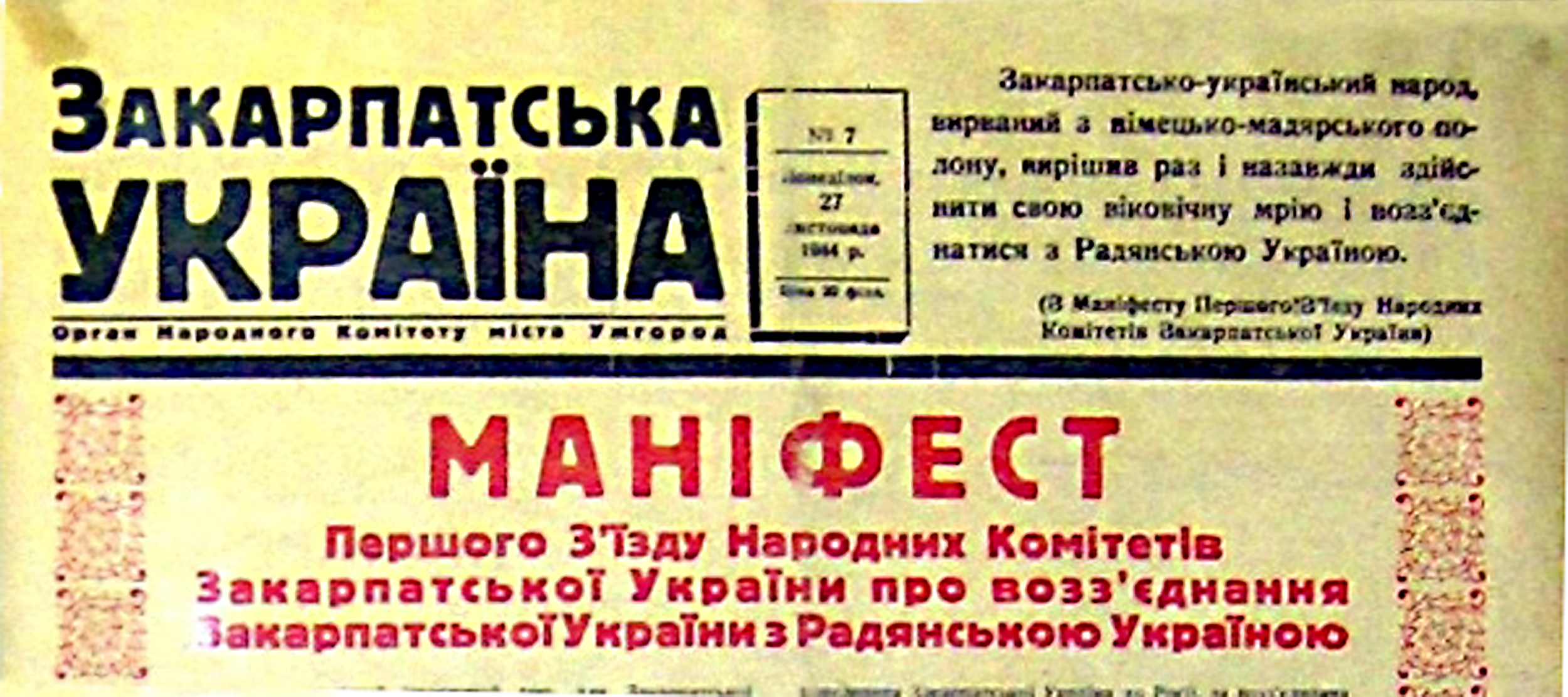

365 days. Our history. 26 November. How Transcarpathia "voluntarily" and decisively became Ukraine (365 днів. Наша історія. 26 листопада. Як Закарпаття "добровільно" і остаточно стало Україною)

'. Poltava 365. 26 November 2018. According to the Soviet–Czechoslovak treaty, it was agreed that once any liberated territory of Czechoslovakia ceased to be a combat zone of the Red Army, those lands would be transferred to full control of the Czechoslovak state. However, after a few weeks, the Red Army and

by Paul Robert Magocsi, Central European University Press, 2015 In November 1944, in

Communist Party of Zakarpattia Ukraine (КОМУНІСТИЧНА ПАРТІЯ ЗАКАРПАТСЬКОЇ УКРАЇНИ)

'.

Political confrontations in Zakarpattia in the fall of 1991. To the 20th Anniversary of Ukrainian Independence. Part 4 (Політичне протистояння на Закарпатті восени 1991 р. До двадцятиріччя Незалежності України. Ч. 4)

'. Zakarpattia online. 22 September 2011 The local

Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a geopolitical term encompassing the countries in Baltic region, Northeast Europe (primarily the Baltic states, Baltics), Central Europe (primarily the Visegrád Group), Eastern Europe, and Southeast Europe (primaril ...

, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast

Zakarpattia Oblast (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Закарпатська область), also referred to as simply Zakarpattia (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Закарпаття; Hungarian language, Hungarian: ''Kárpátalja'') or Transcar ...

.

From the Hungarian conquest

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or Coercion (international relations), coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or ...

of the Carpathian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, with the term Carpathian Basin being sometimes preferred in Hungarian literature, is a large sedimentary basin situated in southeastern Central Europe. After the Treaty of Trianon following World War I, the geomorphologic ...

(at the end of the 9th century) to the end of World War I (Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (; ; ; ), often referred to in Hungary as the Peace Dictate of Trianon or Dictate of Trianon, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference. It was signed on the one side by Hungary ...

in 1920), most of this region was part of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

. In the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, it was part of the First

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

and Second Czechoslovak Republic

The Second Czechoslovak Republic (Czech language, Czech and ), officially the Czecho-Slovak Republic (Czech and Slovak: ''Česko-Slovenská republika''), existed for 169 days, between 30 September 1938 and 15 March 1939. It was c ...

s. Before World War II, the region was annexed by the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

once again when Germany dismembered the Second Czechoslovak Republic.

After the war, it was annexed by the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

.

It is an ethnically diverse region, inhabited mostly by people who regard themselves as ethnic Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

, Rusyns

Rusyns, also known as Carpatho-Rusyns, Carpatho-Russians, Ruthenians, or Rusnaks, are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group from the Carpathian Rus', Eastern Carpathians in Central Europe. They speak Rusyn language, Rusyn, an East Slavic lan ...

, Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an Ethnicity, ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common Culture of Hungary, culture, Hungarian language, language and History of Hungary, history. They also have a notable presence in former pa ...

, Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

, Slovaks

The Slovaks ( (historical Sloveni ), singular: ''Slovák'' (historical: ''Sloven'' ), feminine: ''Slovenka'' , plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history ...

, and Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

. It also has small communities of Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

and Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Romani people, or Roma, an ethnic group of Indo-Aryan origin

** Romani language, an Indo-Aryan macrolanguage of the Romani communities

** Romanichal, Romani subgroup in the United Kingdom

* Romanians (Romanian ...

minorities. Prior to World War II, many more Jews lived in the region, constituting over 13% of its total population in 1930. The most commonly spoken languages are Rusyn, Ukrainian, Hungarian, Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

, Slovak, and Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

.

Toponymy

The name Carpathian Ruthenia is sometimes used for the contiguous cross-border area of Ukraine, Slovakia and Poland inhabited byRuthenians

A ''Ruthenian'' and ''Ruthene'' are exonyms of Latin language, Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common Ethnonym, ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term ...

. The local Ruthenian population self-identifies in different ways: some consider themselves to be a separate and unique Slavic group of Rusyns

Rusyns, also known as Carpatho-Rusyns, Carpatho-Russians, Ruthenians, or Rusnaks, are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group from the Carpathian Rus', Eastern Carpathians in Central Europe. They speak Rusyn language, Rusyn, an East Slavic lan ...

and some consider themselves to be both Rusyns and Ukrainians. To describe their home region, most of them use the term ''Zakarpattia'' (). This is contrasted implicitly with ''Prykarpattia

Prykarpattia () is a Ukrainian term for Ciscarpathia, a physical geographical region for the northeastern Carpathian foothills.Vortman, D. Prykarpattia (ПРИКАРПАТТЯ)'. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.

Located at the outer foot of ...

'' (), an unofficial geographical region in Ukraine, to the immediate north-east of the central area of the Carpathian Range, and potentially including its foothills, the Subcarpathian basin and part of the surrounding plains.

From a Hungarian (and to an extent Slovak and Czech) perspective, the region is usually described as Subcarpathia (literally "below the Carpathians"), although technically this name refers only to a long, narrow basin that flanks the northern side of the mountains.

During the period in which the region was administered by the Hungarian states, it was officially referred to in Hungarian as Kárpátalja (literally: "the base of the Carpathians") or the north-eastern regions of medieval ''Upper Hungary'', which in the 16th century was contested between the Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire.

The Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

name of the region is Maramureș

( ; ; ; ) is a geographical, historical and cultural region in northern Romania and western Ukraine. It is situated in the northeastern Carpathians, along parts of the upper Tisza River drainage basin; it covers the Maramureș Depression and the ...

, which is geographically located in the eastern and south-eastern portions of the region.

During the period of Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

** Fourth Czechoslovak Repu ...

administration in the first half of the 20th century, the region was referred to for a while as ''Rusinsko'' (Ruthenia) or ''Karpatske Rusinsko'', and later as Subcarpathian Rus (Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

and Slovak: ''Podkarpatská Rus'') or Subcarpathian Ukraine (Czech and Slovak: ''Podkarpatská Ukrajina''), and from 1928 as Subcarpathian Ruthenian Land. (Czech: ''Země podkarpatoruská'', Slovak: ''Krajina podkarpatoruská'').

Alternative, unofficial names used in Czechoslovakia before World War II included Subcarpathia (Czech and Slovak: ''Podkarpatsko''), Transcarpathia (Czech and Slovak: ''Zakarpatsko''), Transcarpathian Ukraine (Czech and Slovak: ''Zakarpatská Ukrajina''), Carpathian Rus/Ruthenia (Czech and Slovak: ''Karpatská Rus'') and, occasionally, Hungarian Rus/Ruthenia (; ).

The region declared its independence as Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine or Carpathian Ukraine (, ) was an autonomous region, within the Second Czechoslovak Republic, created in December 1938 and renamed from Subcarpathian Rus', whose full administrative and political autonomy had been confirmed by ...

on March 15, 1939, but was occupied and annexed by Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

on the same day, and remained under Hungarian control until the end of World War II. During this period the region continued to possess a special administration and the term ''Kárpátalja'' was locally used.

In 1944–1946, the region was occupied by the Soviet Army and was a separate political formation known as Transcarpathian Ukraine or Subcarpathian Ruthenia. During this period the region possessed some form of quasi-autonomy with its own legislature, while remaining under the governance of the Communist Party of Transcarpathian Ukraine. After the signing of a treaty between Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as well as the decision of the regional council, Transcarpathia joined the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

as the Zakarpattia Oblast

Zakarpattia Oblast (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Закарпатська область), also referred to as simply Zakarpattia (Ukrainian language, Ukrainian: Закарпаття; Hungarian language, Hungarian: ''Kárpátalja'') or Transcar ...

.

The region has subsequently been referred to as ''Zakarpattia'' () or ''Transcarpathia'', and on occasions as ''Carpathian Rus’'' (), ''Transcarpathian Rus’'' (), or ''Subcarpathian Rus’'' ().

Geography

Carpathian Mountains

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe and Southeast Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Ural Mountains, Urals at and the Scandinav ...

, bordered to the east and south by the Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa (see below) is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. It was once called "the most Hungarian river" because it used to flow entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national bo ...

River, and to the west by the Hornád

The Hornád ( Slovak, ) or Hernád ( Hungarian, ) is a river in eastern Slovakia and north-eastern Hungary.

It is a tributary to the river Slaná (Sajo). The source of the Hornád is the eastern slopes of Kráľova hoľa hill, south of Šuňa ...

and Poprad River

The Poprad (, ) is a river in northern Slovakia and southern Poland, and a tributary of the Dunajec River near Stary Sącz, Poland. It has a length of 170 kilometres (63 km of which are within the Polish borders) and a basin area of 2,0 ...

s. The region borders Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania, and makes up part of the Pannonian Plain

The Pannonian Basin, with the term Carpathian Basin being sometimes preferred in Hungarian literature, is a large sedimentary basin situated in southeastern Central Europe. After the Treaty of Trianon following World War I, the geomorphologic ...

.

The region is predominantly rural and infrastructurally underdeveloped. The landscape is mostly mountainous; it is geographically separated from Ukraine, Slovakia, and Romania by mountains, and from Hungary by the Tisza river. The two major cities are Uzhhorod

Uzhhorod (, ; , ; , ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality on the Uzh, Uzh River in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistan ...

and Mukachevo

Mukachevo (, ; , ; see name section) is a city in Zakarpattia Oblast, western Ukraine. It is situated in the valley of the Latorica River and serves as the administrative center of Mukachevo Raion. The city is a rail terminus and highway junct ...

, both with populations around 100,000. The population of the other five cities (including Khust

Khust (, ; ; ; ; ; ) is a city located on the Khustets River in Zakarpattia Oblast, western Ukraine. It is near the сonfluence of the Tisa and Rika Rivers. It serves as the administrative center of Khust Raion. Population:

Khust was the capi ...

and Berehove

Berehove (, ; , ) is a city in Zakarpattia Oblast, western Ukraine. It is situated near the border with Hungary.

It is the cultural centre of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine, and Hungarians constitute roughly half (a plurality) of its popula ...

) varies between 10,000 and 30,000. Other urban and rural populated places have a population of less than 10,000.

History

Prehistoric cultures

During the LateBronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

in the 2nd millennium BC, the region was characterized by Stanove culture; however, it only gained more advanced metalworking skills with the arrival of Thracians

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared betwee ...

from the South with Kushtanovytsia culture in the 6th-3rd century BC. In the 5th-3rd century BC, Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

arrived from the West, bringing iron-melting skills and La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a Iron Age Europe, European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman Republic, Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age ...

. A Thracian-Celtic symbiosis existed for a time in the region, after which appeared the Bastarnae

The Bastarnae, Bastarni or Basternae, also known as the Peuci or Peucini, were an ancient people who are known from Greek and Roman records to have inhabited areas north and east of the Carpathian Mountains between about 300 BC and about 300 AD, ...

. At that time, the Iranian-speaking Scythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

and later a Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; ; Latin: ) were a large confederation of Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Iranian Eurasian nomads, equestrian nomadic peoples who dominated the Pontic–Caspian steppe, Pontic steppe from about the 5th century BCE to the 4t ...

tribe called the Iazyges

The Iazyges () were an ancient Sarmatians, Sarmatian tribe that traveled westward in 200BC from Central Asia to the steppes of modern Ukraine. In , they moved into modern-day Hungary and Serbia near the Pannonian steppe between the Danube ...

were present in the region. Proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium BC through the 6th ...

settlement began between the 2nd-century BCE and 2nd century CE, and during the Migration Period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

, the region was traversed by Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was par ...

and Gepids

The Gepids (; ) were an East Germanic tribes, East Germanic tribe who lived in the area of modern Romania, Hungary, and Serbia, roughly between the Tisza, Sava, and Carpathian Mountains. They were said to share the religion and language of the G ...

(4th century) and Pannonian Avars

The Pannonian Avars ( ) were an alliance of several groups of Eurasian nomads of various origins. The peoples were also known as the Obri in the chronicles of the Rus' people, Rus, the Abaroi or Varchonitai (), or Pseudo-Avars in Byzantine Empi ...

(6th century).

Slavic settlement

By the 8th and 9th century, the valleys of the Northern and Southern slopes of theCarpathian Mountains

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe and Southeast Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Ural Mountains, Urals at and the Scandinav ...

were "densely" settled by Slavic tribe of White Croats

The White Croats (; ; ; ), also known simply as Croats, were a group of Early Slavs, Early Slavic tribes that lived between East Slavs, East Slavic and West Slavs, West Slavic tribes in the historical region of Galicia (Eastern Europe), Galicia n ...

, who were closely related to East Slavic tribes who inhabited Prykarpattia

Prykarpattia () is a Ukrainian term for Ciscarpathia, a physical geographical region for the northeastern Carpathian foothills.Vortman, D. Prykarpattia (ПРИКАРПАТТЯ)'. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.

Located at the outer foot of ...

, Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

, Transnistria

Transnistria, officially known as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic and locally as Pridnestrovie, is a Landlocked country, landlocked Transnistria conflict#International recognition of Transnistria, breakaway state internationally recogn ...

and Dnieper Ukraine

The term Dnieper Ukraine

(), usually refers to territory on either side of the middle course of the Dnieper River. The Ukrainian name derives from ''nad‑'' (prefix: "above, over") + ''Dnipró'' ("Dnieper") + ''‑shchyna'' (suffix denoting a g ...

. Whereas some White Croats remained behind in Carpathian Ruthenia, others moved southward into the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

in the 7th century. Those who remained were conquered by Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus,.

* was the first East Slavs, East Slavic state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical At ...

in the late 10th century.

Hungarian arrival

In 896 theHungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an Ethnicity, ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common Culture of Hungary, culture, Hungarian language, language and History of Hungary, history. They also have a notable presence in former pa ...

crossed the Carpathian Range and migrated into the Pannonian Basin

The Pannonian Basin, with the term Carpathian Basin being sometimes preferred in Hungarian literature, is a large sedimentary basin situated in southeastern Central Europe. After the Treaty of Trianon following World War I, the geomorpholog ...

. Nestor's Chronicle

The ''Primary Chronicle'', shortened from the common ''Russian Primary Chronicle'' (, commonly transcribed ''Povest' vremennykh let'' (PVL), ), is a chronicle of Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110. It is believed to have been originally compile ...

wrote that Hungarian tribes had to fight against the Volochi and settled among Slavs when on their way to Pannonia. Prince Laborec fell from power under the efforts of the Hungarians and the Kievan forces. According to Gesta Hungarorum

''Gesta Hungarorum'', or ''The Deeds of the Hungarians'', is the earliest book about Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian history which has survived for posterity. Its genre is not chronicle, but ''gesta'', meaning "deeds" or "acts", which is a medie ...

, the Hungarians defeated a united Bulgarian and Byzantine army

The Byzantine army was the primary military body of the Byzantine Empire, Byzantine armed forces, serving alongside the Byzantine navy. A direct continuation of the East Roman army, Eastern Roman army, shaping and developing itself on the legac ...

led by Salan

]

Salan, Salanus or Zalan ( Bulgarian language, Bulgarian and Serbian Cyrillic: Салан or Залан; ; ) was, according to the Gesta Hungarorum, a local Bulgarian voivod (duke) who ruled in the 9th century between Danube and Tisa rivers ...

in the early 10th century on the plains of Alpár, who ruled over territory that was finally conquered by Hungarians. During the tenth and for most of the eleventh century the territory remained a borderland between the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

to the south and the Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus,.

* was the first East Slavs, East Slavic state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical At ...

Principality of Halych

The Principality of Galicia (; ), also known as Principality of Halych or Principality of Halychian Rus, was a medieval East Slavs, East Slavic principality, and one of the main regional states within the political scope of Kievan Rus', establi ...

to the north.

Slavs from the north ( Galicia) and east—who actually arrived from Podolia

Podolia or Podillia is a historic region in Eastern Europe located in the west-central and southwestern parts of Ukraine and northeastern Moldova (i.e. northern Transnistria).

Podolia is bordered by the Dniester River and Boh River. It features ...

via the mountain passes of Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

—continued to settle in small numbers in various parts of the Carpathian borderland, which the Hungarians and other medieval writers referred to as the Marchia Ruthenorum—the Rus' March. These new immigrants, from the north and east, like the Slavs already living in Carpathian Ruthenia, had by the eleventh century come to be known as the people of Rus', or Rusyns

Rusyns, also known as Carpatho-Rusyns, Carpatho-Russians, Ruthenians, or Rusnaks, are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group from the Carpathian Rus', Eastern Carpathians in Central Europe. They speak Rusyn language, Rusyn, an East Slavic lan ...

. Local Slavic nobility often intermarried with the Hungarian nobles

The Kingdom of Hungary held a noble class of individuals, most of whom owned landed property, from the 11th century until the mid-20th century. Initially, a diverse body of people were described as noblemen, but from the late 12th&nbs ...

to the south. Prince Rostislav, a Ruthenian noble unable to continue his family's rule of Kiev, governed a great deal of Transcarpathia from 1243 to 1261 for his father-in-law

A parent-in-law is a person who has a legal affinity (law), affinity with another by being the parent of the other's spouse. Many cultures and legal systems impose duties and responsibilities on persons connected by this relationship. A person i ...

, Béla IV of Hungary

Béla IV (1206 – 3 May 1270) was King of Hungary and King of Croatia, Croatia between 1235 and 1270, and Duke of Styria from 1254 to 1258. As the oldest son of Andrew II of Hungary, King Andrew II, he was crowned upon the initiative of a group ...

. The territory's ethnic diversity increased with the influx of some 40,000 Cuman

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Rus' chronicles, as " ...

settlers, who came to the Pannonian Basin after their defeat by Vladimir II (Monomakh) in the 12th century and their ultimate defeat at the hands of the Mongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

in 1238.

During the early period of Hungarian administration, part of the area was included into the Gyepű

In Middle Ages, medieval Europe, a march or mark was, in broad terms, any kind of borderland, as opposed to a state's "heartland". More specifically, a march was a border between realms or a neutral buffer zone under joint control of two states i ...

border region, while the other part was under county authority and was included into the counties of Ung

Ung or UNG may refer to:

People

* Woong, a Korean given name also spelled Ung

* Ung (surname), a Cambodian and Norwegian surname

* Ung Thị (full name Nguyễn Phúc Ung Thị; 1913–2001), Vietnamese-born American businessman

* Franz Unger (1 ...

, Borsova and Szatmár. Later, the county administrative system was expanded to the whole of Transcarpathia, and the area was divided between the counties of Ung, Bereg, Ugocsa, and Máramaros. At the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, during the collapse of the central power in the Kingdom of Hungary, the region was part of the domains of semi-independent oligarchs Amadeus Aba

Amadeus Aba or Amade Aba (; ; ? – 5 September 1311) was a Hungarian oligarch in the Kingdom of Hungary who ruled ''de facto'' independently the northern and north-eastern counties of the kingdom (today parts of Hungary, Slovakia and Ukrai ...

and Nicholas Pok

Nicholas from the kindred Pok (; ''c''. 1245 – after 19 August 1319; fl. 1270–1319) was a Hungarian influential lord in the Kingdom of Hungary at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. He held positions in the royal court in the 1270s. He ac ...

. Although King Leo I of Galicia–Volhynia (Lev Danylovych) attempted to extend his influence over parts of the Carpathian region during the late 13th century, there is no reliable historical evidence that north-western Carpathian Ruthenia was permanently annexed to his kingdom. Contemporary Hungarian royal charters from the period confirm that the region — including key fortresses like Huszt and Munkács — remained under the control of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Historians such as Gyula Kristó and Pál Engel agree that Leo's interventions were temporary and opportunistic, taking advantage of internal conflicts within Hungary, but they did not lead to lasting occupation.

Thus, the claim that north-western Carpathian Ruthenia belonged to the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia

The Principality or, from 1253, Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, also known as the Kingdom of Ruthenia, Kingdom of Rus', or Kingdom of Russia, also Halych–Volhynian Kingdom was a medieval state in Eastern Europe which existed from 1199 to 1349. I ...

between 1280 and 1320 is not supported by primary sources or mainstream historical scholarship.

The assumption that Transcarpathia briefly came under the rule of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia is, in this context, primarily the result of Ukrainian historiography’s attempt to establish historical rights and continuity over the region — suggesting that "medieval Ukraine" had annexed it even before 1946.

This narrative is further reinforced by the frequent appearance of Transcarpathia on maps of Kievan Rus' as if it had been part of, or directly linked to, Kievan Rus'. However, this claim is not supported by either archaeological or historical evidence. On the contrary, both the historical sources — which indicate the settlement of Ruthenians in the region during the 13th and 14th centuries — and the archaeological record — which shows a lack of Orthodox church remains from that period — argue against such interpretations.

Between the 12th and 15th centuries, the area was probably colonized by Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

groups of Vlach

Vlach ( ), also Wallachian and many other variants, is a term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate speakers of Eastern Romance languages living in Southeast Europe—south of the Danube (the Balkan peninsula) ...

(Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

) highlanders with accompanying Ruthenian populations. Initially, the Romanians were organized into the Voivodeship of Maramureș

The Voivodeship of Maramureș (, or ), was a Romanian voivodeship centered in the region of the same name within the Kingdom of Hungary. It was the most powerful and well-organized Romanian entity in the broader area of Transylvania during th ...

, formally integrated into Hungary in 1402. All the groups, including local Slavic

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Slav ...

population, blended together, creating a distinctive culture from the main Ruthenian-speaking areas. Over time, because of geographical and political isolation from the main Ruthenian-speaking territory, the inhabitants developed distinctive features.

Part of Hungary and Transylvania

In 1526 the region was divided between the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary and the

In 1526 the region was divided between the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary and the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom

The Eastern Hungarian Kingdom ( ) is a modern term coined by some historians to designate the realm of John Zápolya and his son John Sigismund Zápolya, who contested the claims of the House of Habsburg to rule the Kingdom of Hungary from 1526 ...

. Beginning in 1570 the latter transformed to the Principality of Transylvania, which soon fell under Ottoman suzerainty. The part of Transcarpathia under Habsburg administration was included into the Captaincy of Upper Hungary, which was one of the administrative units of the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary. During this period, an important factor in the Ruthenian cultural identity, namely religion, came to the forefront. The Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

(1595) and Union of Uzhhorod

The Union of Uzhhorod (), was a decision by 63 Ruthenian priests of the Orthodox Eparchy of Mukachevo (then divided between the Principality of Transylvania and Royal Hungary of the Habsburg monarchy) to join the Catholic Church made on Apri ...

(1646) were instituted, causing the Byzantine Orthodox Churches of Carpathian and Transcarpathian Rus' to come under the jurisdiction of Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, thus establishing the so-called "Unia" of Eastern Catholic churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, the Ruthenian Catholic Church and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) is a Major archiepiscopal church, major archiepiscopal ''sui iuris'' ("autonomous") Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic church that is based in Ukraine. As a particular church of the Cathol ...

.

In the 17th century (until 1648) the entire region was part of the Principality of Transylvania and between 1682 and 1685 its north-western part was administered by the Ottoman vassal state of Upper Hungary

Upper Hungary (, "Upland"), is the area that was historically the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now mostly present-day Slovakia. The region has also been called ''Felső-Magyarország'' ( literally: "Upper Hungary"; ).

During the ...

, while the south-eastern parts remained under the administration of Transylvania. From 1699 the entire region eventually became part of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

, divided between the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

and the Principality of Transylvania. Later, the entire region was included into the Kingdom of Hungary. Between 1850 and 1860 the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary was divided into five military districts, and the region was part of the Military District of Kaschau.

Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen

After 1867, the region was administratively included intoTransleithania

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen (), informally Transleithania (meaning the lands or region "beyond" the Leitha River), were the Hungarian territories of Austria-Hungary, throughout the latter's entire existence (30 March 1867 – 16 ...

or the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, many nationalist groups vied for unification or alignment with many different possible nationalities, all arguing that the Rus people would be better off uniting with that nation for security or staying within the nation of Hungary. Many of these groups utilized the ethnic makeup of the region, with ideas such as the Lemko-Boiko-Hutsul schema looking to prove the Slavic nature of the Rus, and therefore justifying union with Russia (or later a Ukrainian state) under the claim that the Rus were part of that Slavic cultural sphere. These Rus or Ruthenians would argue this point until the early 1900s when action would be taken.

In 1910, the population of Transcarpathia was 605,942, of which 330,010 (54.5%) were speakers of Ruthenian, 185,433 (30.6%) were speakers of Hungarian, 64,257 (10.6%) were speakers of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, 11,668 (1.9%) were speakers of Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

, 6,346 (1%) were speakers of Slovak or Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

, and 8,228 (1.4%) were speakers of other languages.

* Ung County, Ungvár (Uzhhorod

Uzhhorod (, ; , ; , ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality on the Uzh, Uzh River in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistan ...

)

* Bereg County

Bereg (; ) was an administrative county ( comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now mostly in western Ukraine and a smaller part in northeastern Hungary. The capital of the county was Beregszász ("Berehove" in Ukrainian, ''Bere ...

, Beregszász (Berehove

Berehove (, ; , ) is a city in Zakarpattia Oblast, western Ukraine. It is situated near the border with Hungary.

It is the cultural centre of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine, and Hungarians constitute roughly half (a plurality) of its popula ...

)

* Ugocsa County

Ugocsa was an administrative county (comitatus (Kingdom of Hungary), comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now in north-western Romania () and western Ukraine (). The capital of the county was Nagyszőllős (now Vynohradiv, Ukr ...

, Nagyszőllős (Vynohradiv

Vynohradiv (, ; ; ; ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city in western Ukraine, in Zakarpattia Oblast. It was the center of Vynohradiv Raion and since 2020 it has been incorporated into Berehove Raion. Population:

Names

There are multiple alte ...

)

* Máramaros County

Máramaros County (; ; ; ; ; ) was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now in north-western Romania and western Ukraine. The capital of the county was Máramarossziget (present-day Sighetu Marmație ...

(only the northern part), Máramarossziget (Sighetu Marmației

Sighetu Marmației (, also spelled ''Sighetul Marmației''; or ''Siget''; , ; ; ), until 1960 Sighet, is a city in Maramureș County near the Iza River, in northwestern Romania.

Geography

Sighetu Marmației is situated along the Tisa river o ...

)

Transitional period (1918–1919)

AfterWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Austro-Hungarian monarchy collapsed and the region was briefly (in 1918 and 1919) claimed as part of the independent West Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine (, ) refers to the western territories of Ukraine. There is no universally accepted definition of the territory's boundaries, but the contemporary Ukrainian administrative regions ( oblasts) of Chernivtsi, I ...

Republic. However, for most of this period the region was controlled by the newly formed independent Hungarian Democratic Republic

The First Hungarian Republic (), until 21 March 1919 the Hungarian People's Republic (), was a short-lived unrecognized country, which quickly transformed into a small rump state due to the foreign and military policy of the doctrinaire pacifis ...

, with a short period of West Ukrainian control.

On November 8, 1918, the first National Council (the Ľubovňa Council, which later reconvened as the Prešov

Prešov () is a city in eastern Slovakia. It is the seat of administrative Prešov Region () and Šariš. With a population of approximately 85,000 for the city, and in total more than 100,000 with the urban area, it is the second-largest city i ...

Council) was held in western Ruthenia. The first of many councils, it simply stated the desire of its members to separate from the newly formed Hungarian state but did not specify a particular alternative—only that it must involve the right to self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

.Preclík, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 pages, first issue vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karvina, Czech Republic) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, , pp. 35–53, 106–107, 111–112, 124–125, 128, 129, 132, 140–148, 184–199.

Other councils, such as the Carpatho-Ruthenian National Council meetings in Huszt (Khust

Khust (, ; ; ; ; ; ) is a city located on the Khustets River in Zakarpattia Oblast, western Ukraine. It is near the сonfluence of the Tisa and Rika Rivers. It serves as the administrative center of Khust Raion. Population:

Khust was the capi ...

) (November 1918), called for unification with the West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (; West Ukrainian People's Republic#Name, see other names) was a short-lived state that controlled most of Eastern Galicia from November 1918 to July 1919. It included major cities of Lviv, Ternopil, Kolom ...

. Only in early January 1919 were the first calls heard in Ruthenia for union with Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

.

Rus'ka Krajina

Uzhhorod

Uzhhorod (, ; , ; , ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality on the Uzh, Uzh River in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistan ...

Council (November 9, 1918), declared itself the representative of the Rusyn people

Rusyns, also known as Carpatho-Rusyns, Carpatho-Russians, Ruthenians, or Rusnaks, are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group from the Carpathian Rus', Eastern Carpathians in Central Europe. They speak Rusyn language, Rusyn, an East Slavic lan ...

and began negotiations with Hungarian authorities. These negotiations ultimately resulted in the passage of ''Law no. 10'' by the Hungarian government on December 21, 1918, thereby establishing the autonymous Rusyn province of Rus'ka Krajina from the Rusyn-inhabited parts of four eastern counties (Máramaros County

Máramaros County (; ; ; ; ; ) was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now in north-western Romania and western Ukraine. The capital of the county was Máramarossziget (present-day Sighetu Marmație ...

, Ugocha County, Bereg County

Bereg (; ) was an administrative county ( comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now mostly in western Ukraine and a smaller part in northeastern Hungary. The capital of the county was Beregszász ("Berehove" in Ukrainian, ''Bere ...

, Ung County.

On February 5, 1919, a provisional government for Rus'ka Krajina was established. The "Rus'ka rada

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, also known by its abbreviation RADA (), is a drama school in London, England, which provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in Bloomsbury, Central Lond ...

" (or Rusyn Council), was made up of 42 representatives from the four constituent counties and headed by a chairman, Orest Sabov, and vice-chairman, Avhustyn Shtefan. The following month, on March 4, elections were held for a formal diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

of 36 deputies. Upon election, the new diet requested the Hungarian government define the borders of the autonomous region, which had not yet been elaborated; without an established territory, the deputies argued that the diet was useless.

On March 21, 1919, the Democratic Republic of Hungary was replaced by the Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Hungarian Soviet Republic, also known as the Socialist Federative Soviet Republic of Hungary was a short-lived communist state that existed from 21 March 1919 to 1 August 1919 (133 days), succeeding the First Hungarian Republic. The Hungari ...

, which then announced the existence of a "Soviet Rus'ka Krajina". Elections organized by the new Hungarian government of a people's soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

(council) on April 6 and 7, 1919 led to Rus'ka Krajina then had two councils: the original diet, and the newly elected soviet. Representatives from both councils then decided to join, forming the ''Uriadova rada'' ("Governing Council) of Rus'ka Krajina.

Fall of Soviet Hungary

Prior to this, in July 1918, Rusyn immigrants in the United States had convened and called for completeindependence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

. Failing that, they would try to unite with Galicia and Bukovina

Bukovina or ; ; ; ; , ; see also other languages. is a historical region at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. It is located on the northern slopes of the central Eastern Carpathians and the adjoining plains, today divided betwe ...

; and failing that, they would demand autonomy, though they did not specify under which state. They approached the American government and were told that the only viable option was unification with Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. Their leader, Gregory Zatkovich, then signed the "Philadelphia Agreement" with Czechoslovak President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk Tomáš () is a Czech name, Czech and Slovak name, Slovak given name, equivalent to the name Thomas (name), Thomas. Tomáš is also a surname (feminine: Tomášová). Notable people with the name include:

Given name Sport

*Tomáš Berdych (born 198 ...

, guaranteeing Rusyn autonomy upon unification with Czechoslovakia on 25 October 1918. A referendum was held among American Rusyn parishes in November 1918, with a resulting 67% in favor. Another 28% voted for union with Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, and less than one percent each for Galicia, Hungary and Russia. Less than 2% desired complete independence.

In April 1919, Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

** Fourth Czechoslovak Repu ...

control on the ground was established, when Czechoslovak Army

The Czechoslovak Army (Czech and Slovak: ''Československá armáda'') was the name of the armed forces of Czechoslovakia. It was established in 1918 following Czechoslovakia's declaration of independence from Austria-Hungary.

History

In t ...

troops acting in coordination with Royal Romanian Army forces arriving from the east—both acting under French

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

auspices—entered the area. In a series of battles they defeated and crushed the local militias of the newly formed Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Hungarian Soviet Republic, also known as the Socialist Federative Soviet Republic of Hungary was a short-lived communist state that existed from 21 March 1919 to 1 August 1919 (133 days), succeeding the First Hungarian Republic. The Hungari ...

, which had created the Slovak Soviet Republic

The Slovak Soviet Republic (, , , literally: 'Slovak Republic of Councils') was a short-lived Communist state in southeast Slovakia in existence from 16 June 1919 to 7 July 1919. Its capital city was Prešov, and it was established and headed b ...

and whose proclaimed aim was to "unite the Hungarian, Rusyn and Jewish toilers against the exploiters of the same nationalities". Communist sympathizers accused the Czechoslovaks and Romanians of atrocities, such as public hangings and the clubbing to death of wounded prisoners. This fighting prevented the arrival of Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

aid, for which the Hungarian Communists Hungarian may refer to:

* Hungary, a country in Central Europe

* Kingdom of Hungary, state of Hungary, existing between 1000 and 1946

* Hungarians/Magyars, ethnic groups in Hungary

* Hungarian algorithm, a polynomial time algorithm for solving the ...

hoped in vain; the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

were also too preoccupied with their own civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

to assist.

In May 1919, a Central National Council convened in the United States under Zatkovich and voted unanimously to accept the admission of Carpathian Ruthenia to Czechoslovakia. Back in Ruthenia, on May 8, 1919, a general meeting of representatives from all the previous councils was held, and declared that "The Central Russian National Council... completely endorse the decision of the American Uhro-Rusin Council to unite with the Czech-Slovak nation on the basis of full national autonomy." Note that the Central Russian National Council was an offshoot of the Central Ruthenian National Council and represented a Carpathian branch of the Russophiles movement that existed in the Austrian Galicia.

The Hungarian left-wing writer Béla Illés

Béla Illés (; born 27 April 1968 in Sárvár, Hungary) is a retired Hungarian football player who has spent most of his career playing for MTK Hungária FC. He is considered to be the greatest Hungarian footballer of the 1990s.

He was onl ...

claimed that the meeting was little more than a farce, with various "notables" fetched from their homes by police, formed into a "National Assembly" without any semblance of a democratic process, and effectively ordered to endorse incorporation into Czechoslovakia. He further asserts that Clemenceau had personally instructed the French general on the spot to get the area incorporated into Czechoslovakia "at all costs", so as to create a buffer separating Soviet Ukraine from Hungary, as part of the French anti-Communist " Cordon sanitaire" policy, and that it was the French rather than the Czechoslovaks who made the effective decisions.

Part of Czechoslovakia (1920–1938)

The Article 53, Treaty of St. Germain (September 10, 1919) granted the CarpathianRuthenians

A ''Ruthenian'' and ''Ruthene'' are exonyms of Latin language, Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common Ethnonym, ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term ...

autonomy, which was later upheld to some extent by the Czechoslovak constitution. Some rights were, however, withheld by Prague, which justified its actions by claiming that the process was to be a gradual one; and Ruthenians representation in the national sphere was less than that hoped for. Carpathian Ruthenia included former Hungarian territories of Ung County, Bereg County

Bereg (; ) was an administrative county ( comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now mostly in western Ukraine and a smaller part in northeastern Hungary. The capital of the county was Beregszász ("Berehove" in Ukrainian, ''Bere ...

, Ugocsa County

Ugocsa was an administrative county (comitatus (Kingdom of Hungary), comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now in north-western Romania () and western Ukraine (). The capital of the county was Nagyszőllős (now Vynohradiv, Ukr ...

and Máramaros County

Máramaros County (; ; ; ; ; ) was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now in north-western Romania and western Ukraine. The capital of the county was Máramarossziget (present-day Sighetu Marmație ...

.

After the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

, Transcarpathia became part of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. Whether this was widely popular among the mainly peasant population, is debatable; clearly, however, what mattered most to Ruthenians was not which country they would join, but that they be granted autonomy within it. After their experience of Magyarization

Magyarization ( , also Hungarianization; ), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, adop ...

, few Carpathian Rusyns were eager to remain under Hungarian rule, and they desired to ensure self-determination. According to the Czechoslovak Constitution of 1920

The Czechoslovak Constitution of 1920 was the second constitution of Czechoslovakia. Ratified after World War I, the constitution established Czechoslovakia as a democratic republic. It was adopted by the National Assembly on 29 February 1920 and ...

, the former region of the Kingdom of Hungary, Ruthenian Land (''Ruszka Krajna''), was officially renamed to Subcarpathian Ruthenia (''Podkarpatská Rus'').

In 1920, the area was used as a conduit for arms and ammunition for the anti-Soviet Poles fighting in the Polish-Soviet War directly to the north, while local Communists sabotaged the trains and tried to help the Soviet side. During and after the war many Ukrainian nationalists

Ukrainian nationalism (, ) is the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The origins of modern Ukrainian nationalism emerge during the Cossack uprising against the Poli ...

in East Galicia

Eastern Galicia (; ; ) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil), having also essential historic importance in Poland.

Galicia was formed within the Austrian Empire during the year ...

who opposed both Polish and Soviet rule fled to Carpathian Ruthenia.

Gregory Žatkovich was appointed governor of the province by Masaryk on April 20, 1920, and resigned almost a year later, on April 17, 1921, to return to his law practice in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, US. The reason for his resignation was dissatisfaction with the borders with Slovakia. His tenure is a historical anomaly as the only American citizen ever acting as governor of a province that later became a part of the USSR.

Subcarpathian Rus' (1928–1939)

In 1928,Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

was divided into four provinces: Bohemia, Moravia-Silesia, Slovakia, and the Subcarpathian Rus'. The main town of the region, and its capital until 1938, was Užhorod

Uzhhorod (, ; , ; , ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality on the Uzh, Uzh River in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistan ...

. It had an area of , and its 1921 population was estimated as being 592,044.

In the period 1918–1938 the Czechoslovak government attempted to bring the Subcarpathian Rus', with 70% of the population illiterate, no industry, and a herdsman way of life, up to the level of the rest of Czechoslovakia. Thousands of Czech teachers, policemen, clerks and businessmen went to the region. The Czechoslovak government built thousands of kilometers of railways, roads, airports, and hundreds of schools and residential buildings.

The Rusyn people decided to join the new state of Czechoslovakia, a decision that happened parallel to other events that affected these proceedings. At the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

, several other countries (including Hungary, Ukraine and Russia) laid claim to Carpathian Rus'. The Allies, however, had few alternatives to choosing Czechoslovakia. Hungary had lost the war and therefore gave up its claims; Ukraine was seen as politically unviable; and Russia was in the midst of a civil war. Thus the only importance of Rusyns' decision to become part of Czechoslovakia was in creating, at least initially, good relations between the leaders of Carpathian Rus' and Czechoslovakia. The Ukrainian language

Ukrainian (, ) is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic language, spoken primarily in Ukraine. It is the first language, first (native) language of a large majority of Ukrainians.

Written Ukrainian uses the Ukrainian alphabet, a variant of t ...

was not actively persecuted in Czechoslovakia during the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, unlike in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

. Serhy Yekelchyk ''"Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation"'', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

(2007), , pp. 128–130 73 percent of local parents voted against Ukrainian language education for their children in a referendum conducted in Subcarpathian Rus' in 1937.

Carpathian Ukraine (1938–1939)

First Vienna Award

The First Vienna Award was a treaty signed on 2 November 1938 pursuant to the Vienna Arbitration, which took place at Vienna's Belvedere Palace. The arbitration and award were direct consequences of the previous month's Munich Agreement, whic ...

—a result of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

—Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

ceded southern Carpathian Rus to Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

. The remainder of Subcarpathian Rus' received autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

, with Andrej Bródy as prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the autonomous government. After the resignation of the government following a local political crisis, Avhustyn Voloshyn

The Rt Rev. Avgustyn Ivanovych Monsignor Voloshyn (, , 17 March 1874 – 19 July 1945), also known as Augustin Voloshyn, was a Carpatho-Ukrainian politician, teacher, essayist, and Greek Catholic

priest of the Mukacheve eparchy in Czechoslov ...

became prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the new government. In December 1938, Subcarpathian Rus' was renamed to Carpathian Ukraine.

Following the Slovak proclamation of independence on March 14, 1939, and the Nazis' seizure of the Czech lands on March 15, Carpathian Ukraine declared its independence as the Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a state in which political power rests with the public (people), typically through their representatives—in contrast to a monarchy. Although a ...

, with Avhustyn Voloshyn

The Rt Rev. Avgustyn Ivanovych Monsignor Voloshyn (, , 17 March 1874 – 19 July 1945), also known as Augustin Voloshyn, was a Carpatho-Ukrainian politician, teacher, essayist, and Greek Catholic

priest of the Mukacheve eparchy in Czechoslov ...

as head of state, and was immediately occupied and annexed by Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, restoring provisionally the former counties of Ung

Ung or UNG may refer to:

People

* Woong, a Korean given name also spelled Ung

* Ung (surname), a Cambodian and Norwegian surname

* Ung Thị (full name Nguyễn Phúc Ung Thị; 1913–2001), Vietnamese-born American businessman

* Franz Unger (1 ...

, Bereg and partially Máramaros.

Governorate of Subcarpathia (1939–1945)

On March 23, 1939, Hungaryannexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

further territories disputed with Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

bordering with the west of the former Carpatho-Rus. The Hungarian invasion was followed by a few weeks of terror in which more than 27,000 people were shot dead without trial and investigation. Over 75,000 Ukrainians decided to seek asylum in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

; of those almost 60,000 of them died in Gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

prison-camps. Others joined the remaining Czech troops from the Czechoslovak army-in-exile.Today is the 80th anniversary of the proclamation of the Carpathian UkraineUkrinform

The National News Agency of Ukraine (), or Ukrinform (), is a state information and news agency, and international broadcaster of Ukraine. It was founded in 1918 during the Ukrainian War of IndependenceCarpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine or Carpathian Ukraine (, ) was an autonomous region, within the Second Czechoslovak Republic, created in December 1938 and renamed from Subcarpathian Rus', whose full administrative and political autonomy had been confirmed by ...

, in the territory annexed the Governorate of Subcarpathia was installed and divided into three, the administrative branch offices of Ung (), Bereg () and Máramaros () governed from Ungvár

Uzhhorod (, ; , ; , ) is a city and municipality on the Uzh River in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistant from the Baltic, the Adriatic and the Black Sea (650–69 ...

, Munkács and Huszt respectively, having Hungarian and Rusyn language

Rusyn ( ; ; )http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2781/1/2011BaptieMPhil-1.pdf , p. 8. is an East Slavic language spoken by Rusyns in parts of Central and Eastern Europe, and written in the Cyrillic script. The majority of speakers live in Carpathian Rut ...

as official languages.

Mukachevo

Mukachevo (, ; , ; see name section) is a city in Zakarpattia Oblast, western Ukraine. It is situated in the valley of the Latorica River and serves as the administrative center of Mukachevo Raion. The city is a rail terminus and highway junct ...

, where they constituted 43% of the prewar population.

After the German occupation of Hungary (19 March 1944) the pro-Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

policies of the Hungarian government resulted in emigration and deportation of Hungarian-speaking Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

s, and other groups living in the territory were decimated by war.

During the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

, 17 main ghettos were set up in cities in Carpathian Ruthenia, from which all Jews were taken to Auschwitz

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschw ...

for extermination. Ruthenian ghettos were set up in May 1944 and liquidated by June 1944. Most of the Jews of Transcarpathia were killed, though a number survived, either because they were hidden by their neighbours, or were forced into labour battalion

Labour battalions have been a form of alternative service or unfree labour in various countries in lieu of or resembling regular military service. In some cases they were the result of some kind of discriminative segregation of the population, ...

s, which often guaranteed food and shelter.

The end of the war had a significant impact on the ethnic Hungarian population of the area: 10,000 fled before the arrival of Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

forces. Many of the remaining adult men (25,000) were deported to the Soviet Union; about 30% of them died in Soviet labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see British and American spelling differences, spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are unfree labour, forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have ...