Tonypandy Riot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Miners' Strike of 1910–11 was a violent attempt by coal miners to maintain wages and working conditions in parts of South Wales, where wages had been kept low by a cartel of mine owners.

What became known as the Tonypandy riots of 1910 and 1911 (sometimes collectively known as the Rhondda riots) were a series of violent confrontations between the striking coal

During the evening of rioting, properties in Tonypandy were damaged, and some looting took place. Shops were smashed systematically but not indiscriminately. There was little looting, but some rioters wore clothes taken from the shops and paraded in a festival atmosphere. Women and children were involved in considerable numbers, as they had been outside the Glamorgan colliery. No police were seen at the town square until the Metropolitan Police arrived around 10:30 pm, almost three hours after the rioting began, when the disturbance subsided of its own accord. A few shops remained untouched, notably that of the chemist Willie Llewellyn, which was rumoured to have been spared because he had been a famous Welsh international rugby footballer.

A small police presence might have deterred window-breakages, but police had been moved from the streets to protect the residences of mine owners and managers.

At 1:20 am on 9 November, orders were sent to Colonel Currey at Cardiff to despatch a squadron of the 18th Hussars to reach

During the evening of rioting, properties in Tonypandy were damaged, and some looting took place. Shops were smashed systematically but not indiscriminately. There was little looting, but some rioters wore clothes taken from the shops and paraded in a festival atmosphere. Women and children were involved in considerable numbers, as they had been outside the Glamorgan colliery. No police were seen at the town square until the Metropolitan Police arrived around 10:30 pm, almost three hours after the rioting began, when the disturbance subsided of its own accord. A few shops remained untouched, notably that of the chemist Willie Llewellyn, which was rumoured to have been spared because he had been a famous Welsh international rugby footballer.

A small police presence might have deterred window-breakages, but police had been moved from the streets to protect the residences of mine owners and managers.

At 1:20 am on 9 November, orders were sent to Colonel Currey at Cardiff to despatch a squadron of the 18th Hussars to reach

online

* * Smith, David. "Tonypandy 1910: definitions of community." ''Past & Present'' 87 (1980): 158–184

online

* Smith, David. "From Riots to Revolt: Tonypandy and The Miners’ Next Step," in Trevor Herbert and Gareth Elwyn Jones (eds), ''Wales 1880–1914'' (University of Wales Press, 1988) * Stephenson, Charles. "Chapter 2: South Wales Strife (2): Tonypandy" in ''Churchill as Home Secretary: Suffragettes, Strikes and Social Reform, 1910–1911'' (Pen and Sword, 2023) ch. 3

Rhondda—the story of coal

pp. 124–126 of 126-page download at Rhondda Cynon Taf Library Service (37mB) * Carradice, Phi

at BBC Wales History, 3 November 2010

History of the Cambrian Combine miners' strike and Tonypandy Riots

The Rhondda Riots of 1910–1911

on website of South Wales Police

Tonypandy 1910

Coalfield web materials from the University of Wales, Swansea, with further reading and external links

on Welsh Coalmines historical website * {{usurped,

Commemorating the 100th Anniversary

} A heritage page of Rhondda Cynon Taf Council

Cambrian Combine miners strike and Tonypandy riot, 1910 - Sam Lowry

– A brief history of the background to the dispute, the strike and its outcome

Did Churchill Send Troops Against Strikers? "Guilty with an Explanation"

Churchill's decisions to use troops against strikers prior to WW1

The towns in Wales where Churchill was loathed

How Churchill's reputation was still tarnished 50 years after Tonypandy 1910 in Wales 1911 in Wales 1910 riots Labour disputes in Wales Mining in Wales Miners' labour disputes in the United Kingdom Riots and civil disorder in Wales 1911 riots Winston Churchill Coal in Wales 1911 labor disputes and strikes

miners

A miner is a person who extracts ore, coal, chalk, clay, or other minerals from the earth through mining. There are two senses in which the term is used. In its narrowest sense, a miner is someone who works at the rock face (mining), face; cutt ...

and police that took place at various locations in and around the Rhondda

Rhondda , or the Rhondda Valley ( ), is a former coalmining area in South Wales, historically in the county of Glamorgan. It takes its name from the River Rhondda, and embraces two valleys – the larger Rhondda Fawr valley (, 'large') and t ...

mines of the Cambrian Combine, a cartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collaborate with each other as well as agreeing not to compete with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. A cartel is an organization formed by producers ...

of mining companies formed to regulate prices and wages in South Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

.

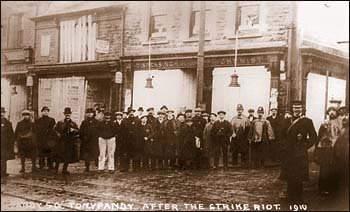

The disturbances and the confrontations were the culmination of the industrial dispute between workers and the mine owners. The term "Tonypandy riot" initially applied to specific events on the evening of Tuesday 8 November 1910, when strikers smashed windows of businesses in Tonypandy. There was hand-to-hand fighting between the strikers and the Glamorgan Constabulary, which was reinforced by the Bristol Constabulary.

Home Secretary Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

's decision to agree to the government's decision to send the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

to reinforce the police shortly after 8 November riot caused rumours that generated much ill feeling towards him in South Wales. Historians such as Paul Addison, however, argue that Churchill did his best to prevent violence; he promised miners that peaceful conduct would be rewarded with sympathetic arbitration. When major riots erupted he sent troops in but "made strenuous efforts to avoid direct confrontation".

Background

The conflict arose when the Naval Colliery Company opened a new coal seam at the Ely Pit in Penygraig. After a short test period to determine what would be the future rate of extraction, owners claimed that the miners deliberately worked more slowly than possible. The roughly-70 miners at the seam argued that the new seam was more difficult to work than others because of a stone band that ran through it. On 1 September 1910, the owners posted a lock-out notice at the mine that closed the site to all 950 workers, not just the 70 at the newly opened Bute seam. The Ely Pit miners reacted by going on strike. The Cambrian Combine then called in strikebreakers from outside the area to which the miners responded by picketing the work site. On 1 November, the miners of theSouth Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

coalfield were balloted for strike action by the South Wales Miners' Federation

The South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF), nicknamed "The Fed", was a trade union for coal miners in South Wales. It survives as the South Wales Area of the National Union of Mineworkers.

Forerunners

The Amalgamated Association of Miners ( ...

, resulting in the 12,000 men working for the mines owned by the Cambrian Combine going on strike. A conciliation board was formed to reach an agreement, with William Abraham acting on behalf of the miners and F. L. Davis for the owners. Although an agreed wage of 2''s'' 3''d'' per ton was arrived at, the Cambrian Combine workmen rejected the agreement.

On 2 November, the authorities in South Wales were enquiring about the procedure for requesting military aid in the event of disturbances caused by the striking miners. The Glamorgan Constabulary's resources were stretched, as in addition to the Cambrian Combine dispute, there was a month-old strike in the neighbouring Cynon Valley, and the Chief Constable of Glamorgan

Glamorgan (), or sometimes Glamorganshire ( or ), was Historic counties of Wales, one of the thirteen counties of Wales that existed from 1536 until their abolishment in 1974. It is located in the South Wales, south of Wales. Originally an ea ...

had by Sunday, 6 November, assembled 200 imported police in the Tonypandy area.

Riots at Tonypandy

By this time, strikers had successfully shut down all local pits, except Llwynypia colliery. On 6 November, miners became aware of the owners' intention to deploystrikebreakers

A strikebreaker (sometimes pejoratively called a scab, blackleg, bootlicker, blackguard or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers may be current employees ( union members or not), or new hires to keep the org ...

to keep pumps and ventilation going at the Glamorgan Colliery in Llwynypia. On Monday, 7 November, strikers surrounded and picketed the Glamorgan Colliery to prevent such workers from entering. That resulted in sharp skirmishes with police officers posted inside the site. Although miners' leaders called for calm, a small group of strikers began stoning the pump-house. A portion of the wooden fence surrounding the site was torn down. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued between miners and police. After repeated baton charges, police drove strikers back towards Tonypandy Square, just after midnight. Between 1 am and 2 am on 8 November, a demonstration at Tonypandy Square was dispersed by Cardiff

Cardiff (; ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. Cardiff had a population of in and forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area officially known as the City and County of Ca ...

Police, using truncheons, resulting in casualties on both sides. That led Glamorgan

Glamorgan (), or sometimes Glamorganshire ( or ), was Historic counties of Wales, one of the thirteen counties of Wales that existed from 1536 until their abolishment in 1974. It is located in the South Wales, south of Wales. Originally an ea ...

's chief constable, Lionel Lindsay, supported by the general manager of the Cambrian Combine, to request military support from the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

.

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

learned of that development and, after discussions with the War Office, delayed action on the request. Churchill felt that the local authorities were overreacting and believed that the Liberal government could calm matters down. He instead despatched Metropolitan Police officers

Metropolitan may refer to:

Areas and governance (secular and ecclesiastical)

* Metropolitan archdiocese, the jurisdiction of a metropolitan archbishop

** Metropolitan bishop or archbishop, leader of an ecclesiastical "mother see"

* Metropolitan ar ...

, both on foot and mounted, and sent some cavalry troops to Cardiff. He did not specifically deploy cavalry but authorised their use by civil authorities if it was deemed necessary. Churchill's personal message to strikers was, "We are holding back the soldiers for the present and sending only police". Despite that assurance, the local stipendiary magistrate sent a telegram to London later that day and requested military support, which the Home Office authorised. Troops were deployed after the skirmish at the Glamorgan Colliery on 7 November but before rioting on the evening of 8 November.

During the evening of rioting, properties in Tonypandy were damaged, and some looting took place. Shops were smashed systematically but not indiscriminately. There was little looting, but some rioters wore clothes taken from the shops and paraded in a festival atmosphere. Women and children were involved in considerable numbers, as they had been outside the Glamorgan colliery. No police were seen at the town square until the Metropolitan Police arrived around 10:30 pm, almost three hours after the rioting began, when the disturbance subsided of its own accord. A few shops remained untouched, notably that of the chemist Willie Llewellyn, which was rumoured to have been spared because he had been a famous Welsh international rugby footballer.

A small police presence might have deterred window-breakages, but police had been moved from the streets to protect the residences of mine owners and managers.

At 1:20 am on 9 November, orders were sent to Colonel Currey at Cardiff to despatch a squadron of the 18th Hussars to reach

During the evening of rioting, properties in Tonypandy were damaged, and some looting took place. Shops were smashed systematically but not indiscriminately. There was little looting, but some rioters wore clothes taken from the shops and paraded in a festival atmosphere. Women and children were involved in considerable numbers, as they had been outside the Glamorgan colliery. No police were seen at the town square until the Metropolitan Police arrived around 10:30 pm, almost three hours after the rioting began, when the disturbance subsided of its own accord. A few shops remained untouched, notably that of the chemist Willie Llewellyn, which was rumoured to have been spared because he had been a famous Welsh international rugby footballer.

A small police presence might have deterred window-breakages, but police had been moved from the streets to protect the residences of mine owners and managers.

At 1:20 am on 9 November, orders were sent to Colonel Currey at Cardiff to despatch a squadron of the 18th Hussars to reach Pontypridd

Pontypridd ( , ), Colloquialism, colloquially referred to as ''Ponty'', is a town and a Community (Wales), community in Rhondda Cynon Taf, South Wales, approximately 10 miles north west of Cardiff city centre.

Geography

Pontypridd comprises the ...

at 8:15 am. Upon arrival, one contingent patrolled Aberaman and another was sent to Llwynypia, where it patrolled all day. Returning to Pontypridd at night, the troops arrived at Porth as a disturbance was breaking out, and then maintained order until the arrival of the Metropolitan Police.

Although no authentic record exists of casualties since many miners would have refused treatment for fear of prosecution for their part in the riots, nearly 80 police and over 500 citizens were injured. One miner, Samuel Rhys, died of head injuries that were said to have been inflicted by a policeman's baton, but the verdict of the coroner's jury was cautious: "We agree that Samuel Rhys died from injuries he received on 8 November caused by some blunt instrument. The evidence is not sufficiently clear to us how he received those injuries." Similarly, the medical evidence concluded, "The fracture had been caused by a blunt instrument—it might have been caused by a policeman's truncheon or by two of the several weapons used by the strikers, which were produced in court." Authorities had reinforced the town with 400 policemen, one company of the Lancashire Fusiliers, billeted at Llwynypia, and the squadron of the 18th Hussars.

Thirteen miners from Gilfach Goch were arrested and prosecuted for their part in the unrest. The trial of the thirteen occupied six days in December. During the trial, they were supported by marches and demonstrations by up to 10,000 men, who were refused entry to the town. Custodial terms of two to six weeks were issued to some of the respondents; others were discharged or fined.

Reaction to riots

Purported eyewitness accounts of alleged shootings persisted and were relayed by word of mouth. In some instances, it was said that there were many shots and fatalities. There are no records of any shots being fired by troops. In fact, relations between the miners and the 18th Hussars were surprisingly cordial. The two groups never came to loggerheads and spent much of their time engaged in friendly games of football against each other. The only recorded death was Samuel Rhys. In the autobiographical "documentary novel" ''Cwmardy'', the later communist trade union organiser Lewis Jones presents a stylistically romantic but closely detailed account of the riots and their agonising domestic and social consequences. The account was criticised for its creative approach to truth. For example, in the chapter "Soldiers are sent to the Valley", he narrates an incident in which eleven strikers are killed by two volleys of rifle fire in the town square after which the miners adopt a grimly retaliatory stance. In that account, the end of the strike is hastened by organised terror directed at mine managers, leading to introduction of a minimum wage act by the government that is hailed as a victory by the strikers. The accuracy of the account is disputed. A more official version states, "The strike finally ended in August 1911, with the workers forced to accept the 2''s'' 3''d'' per ton negotiated by William Abraham MP prior to the strike ... the workers actually returning to work on the first Monday in September", ten months after the strike began and twelve months after the lock-out that had started the confrontation.Criticism of Churchill

Churchill's role in the events at Tonypandy during the conflict left anger towards him in South Wales that still persists today. The main point of contention was his decision to allow troops to be sent to Wales. Although this was an unusual move and was seen by those in Wales as an overreaction, his Tory opponents suggested that he should have acted with greater vigour. The troops acted more circumspectly and were commanded with more common sense than the police, whose role under Lionel Lindsay was, in the words of historian David Smith, "more like an army of occupation". The incident continued to haunt Churchill throughout his career. Such was the strength of feeling, that almost forty years later, when speaking in Cardiff during the general election campaign of 1950, this time as Conservative Party leader, Churchill was forced to address the issue, stating: "When I was Home Secretary in 1910, I had a great horror and fear of having to become responsible for the military firing on a crowd of rioters and strikers. Also, I was always in sympathy with the miners..." A major factor in the dislike of Churchill's use of the military was not in any action undertaken by the troops, but the fact that their presence prevented any strike action which might have ended the strike early in the miners' favour. The troops also ensured that trials of rioters, strikers and miners' leaders would take place and be successfully prosecuted inPontypridd

Pontypridd ( , ), Colloquialism, colloquially referred to as ''Ponty'', is a town and a Community (Wales), community in Rhondda Cynon Taf, South Wales, approximately 10 miles north west of Cardiff city centre.

Geography

Pontypridd comprises the ...

in 1911. The defeat of the miners in 1911 was, in the eyes of much of the local community, a direct consequence of state intervention without any negotiation; that the strikers were breaking the law was not a factor with many locals. This result was seen as a direct result of Churchill's actions.

Political fallout for Churchill also continued. In 1940, when Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

's war-time government was faltering, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

secretly warned that the Labour Party might not follow Churchill because of his association with Tonypandy. There was uproar in the House of Commons in 1978 when Churchill's grandson, also named Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, was asking a question, during Prime Minister's Questions, on miners' pay; he was warned by the Labour leader and Prime Minister James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005) was a British statesman and Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the L ...

not to pursue "the vendetta of your family against the miners of Tonypandy". In 2010, ninety-nine years after the riots, a Welsh local council made objections to an old military base being named after Churchill in the Vale of Glamorgan

The Vale of Glamorgan ( ), locally referred to as ''The Vale'', is a Principal areas of Wales, county borough in the South East Wales, south-east of Wales. It borders Bridgend County Borough to the west, Cardiff to the east, Rhondda Cynon Taf t ...

because of his sending troops into the Rhondda Valley.

Historical myth

The Tonypandy riots are subject of a popular historical myth that troops fired on the miners. Josephine Tey refers to this in her novel '' The Daughter of Time'', and coined the term "tonypandy" to refer to "when a historical event is reported and memorialized inaccurately but consistently until the resulting fiction is believed to be the truth".See also

* Llanelli railway strike, 1911 * National coal strike of 1912References

Further reading

* Addison, Paul. ''Churchill on the Home Front 1900-1955'' (Pimlico, 1992) pp. 138–145. * * McEwen, John M. "Tonypandy: Churchill's Albatross," ''Queen's Quarterly'' (1971) 78#1 pp. 83–94. * Morgan, Kenneth O. ''Rebirth of a Nation: Wales, 1880-1980'' (Oxford UP, 1981) pp. 146–153. * O'Brien, Anthony Mòr. "Churchill and the Tonypandy Riots," '' Welsh History Review'' (1994), 17#1 pp 67–99.online

* * Smith, David. "Tonypandy 1910: definitions of community." ''Past & Present'' 87 (1980): 158–184

online

* Smith, David. "From Riots to Revolt: Tonypandy and The Miners’ Next Step," in Trevor Herbert and Gareth Elwyn Jones (eds), ''Wales 1880–1914'' (University of Wales Press, 1988) * Stephenson, Charles. "Chapter 2: South Wales Strife (2): Tonypandy" in ''Churchill as Home Secretary: Suffragettes, Strikes and Social Reform, 1910–1911'' (Pen and Sword, 2023) ch. 3

External links

Rhondda—the story of coal

pp. 124–126 of 126-page download at Rhondda Cynon Taf Library Service (37mB) * Carradice, Phi

at BBC Wales History, 3 November 2010

History of the Cambrian Combine miners' strike and Tonypandy Riots

The Rhondda Riots of 1910–1911

on website of South Wales Police

Tonypandy 1910

Coalfield web materials from the University of Wales, Swansea, with further reading and external links

on Welsh Coalmines historical website * {{usurped,

Commemorating the 100th Anniversary

} A heritage page of Rhondda Cynon Taf Council

Cambrian Combine miners strike and Tonypandy riot, 1910 - Sam Lowry

– A brief history of the background to the dispute, the strike and its outcome

Did Churchill Send Troops Against Strikers? "Guilty with an Explanation"

Churchill's decisions to use troops against strikers prior to WW1

The towns in Wales where Churchill was loathed

How Churchill's reputation was still tarnished 50 years after Tonypandy 1910 in Wales 1911 in Wales 1910 riots Labour disputes in Wales Mining in Wales Miners' labour disputes in the United Kingdom Riots and civil disorder in Wales 1911 riots Winston Churchill Coal in Wales 1911 labor disputes and strikes