Tito Lopez Combo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 until his death in 1980. During

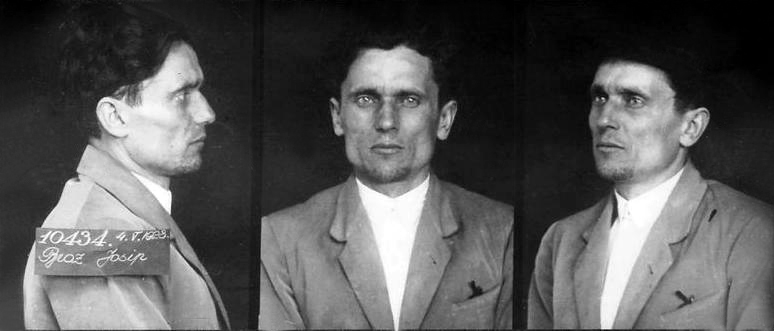

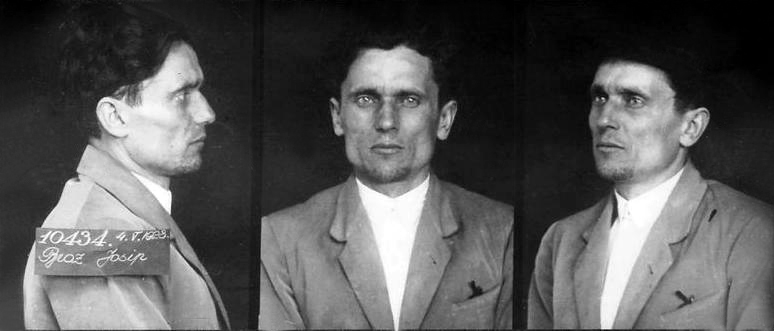

In February 1928, Broz was one of 32 delegates to the conference of the Croatian branch of the CPY. During the conference, he condemned factions within the party, including those that advocated a

In February 1928, Broz was one of 32 delegates to the conference of the Croatian branch of the CPY. During the conference, he condemned factions within the party, including those that advocated a

During this time, Tito wrote articles on the duties of imprisoned communists and on trade unions. He was in Ljubljana when

During this time, Tito wrote articles on the duties of imprisoned communists and on trade unions. He was in Ljubljana when

On 6 April 1941, Axis powers, Axis forces invasion of Yugoslavia, invaded Yugoslavia. On 10 April 1941, Slavko Kvaternik proclaimed the Independent State of Croatia, and Tito responded by forming a Military Committee within the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY). Attacked from all sides, the Royal Yugoslav Army, armed forces of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia quickly crumbled. On 17 April 1941, after Peter II of Yugoslavia, King Peter II and other members of the government Yugoslav government-in-exile, fled the country, the remaining representatives of the government and military met with German officials in

On 6 April 1941, Axis powers, Axis forces invasion of Yugoslavia, invaded Yugoslavia. On 10 April 1941, Slavko Kvaternik proclaimed the Independent State of Croatia, and Tito responded by forming a Military Committee within the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY). Attacked from all sides, the Royal Yugoslav Army, armed forces of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia quickly crumbled. On 17 April 1941, after Peter II of Yugoslavia, King Peter II and other members of the government Yugoslav government-in-exile, fled the country, the remaining representatives of the government and military met with German officials in  Tito stayed in Belgrade until 16 September 1941, when he, together with all members of the CPY, left Belgrade to travel to rebel-controlled territory. To leave Belgrade Tito used documents given to him by Dragoljub Milutinović, who was a ''voivode'' with the collaborationism, collaborationist Pećanac Chetniks. Since Pećanac was already fully co-operating with Germans by that time, this fact caused some to speculate that Tito left Belgrade with the blessing of the Germans because his task was to divide rebel forces, similar to Lenin's arrival in Russia. Tito travelled by train through Stalać and Čačak and arrived to the village of Robaje on 18 September 1941.

Despite conflicts with the rival monarchic Chetnik movement, Tito's

Tito stayed in Belgrade until 16 September 1941, when he, together with all members of the CPY, left Belgrade to travel to rebel-controlled territory. To leave Belgrade Tito used documents given to him by Dragoljub Milutinović, who was a ''voivode'' with the collaborationism, collaborationist Pećanac Chetniks. Since Pećanac was already fully co-operating with Germans by that time, this fact caused some to speculate that Tito left Belgrade with the blessing of the Germans because his task was to divide rebel forces, similar to Lenin's arrival in Russia. Tito travelled by train through Stalać and Čačak and arrived to the village of Robaje on 18 September 1941.

Despite conflicts with the rival monarchic Chetnik movement, Tito's  On 12 August 1944, Winston Churchill met Tito in Naples for a deal. On 12 September 1944, Peter II of Yugoslavia, King Peter II called on all Yugoslavs to come together under Tito's leadership and stated that those who did not were "traitors", by which time Tito was recognised by all Allied authorities (including the government-in-exile) as the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, in addition to the commander-in-chief of the Yugoslav forces. On 28 September 1944, the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) reported that Tito signed an agreement with the

On 12 August 1944, Winston Churchill met Tito in Naples for a deal. On 12 September 1944, Peter II of Yugoslavia, King Peter II called on all Yugoslavs to come together under Tito's leadership and stated that those who did not were "traitors", by which time Tito was recognised by all Allied authorities (including the government-in-exile) as the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, in addition to the commander-in-chief of the Yugoslav forces. On 28 September 1944, the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) reported that Tito signed an agreement with the

On 7 March 1945, the Provisional Government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, provisional government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (DFY) was assembled in

On 7 March 1945, the Provisional Government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, provisional government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (DFY) was assembled in

Unlike other states in east-central Europe liberated by allied forces, Yugoslavia liberated itself from Axis domination with limited direct support from the

Unlike other states in east-central Europe liberated by allied forces, Yugoslavia liberated itself from Axis domination with limited direct support from the  The Soviet answer on 4 May admonished Tito and the

The Soviet answer on 4 May admonished Tito and the  One significant consequence of the tension arising between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union was Tito's decision to begin large-scale repression against enemies of the government. This repression was not limited to known and alleged Stalinists but also included members of the Communist Party or anyone exhibiting sympathy towards the Soviet Union. Prominent partisans, such as Vlado Dapčević and Dragoljub Mićunović, were victims of this period of strong repression, which lasted until 1956 and was marked by significant violations of human rights. Tens of thousands of political opponents served in forced labour camps, such as Goli Otok (meaning Barren Island), and hundreds died. An often disputed but relatively feasible number that was put forth by the Yugoslav government itself in 1964 places the number of Goli Otok inmates incarcerated between 1948 and 1956 to be 16,554, with less than 600 having died during detention. The facilities at Goli Otok were abandoned in 1956, and jurisdiction of the now-defunct political prison was handed over to the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia.

One significant consequence of the tension arising between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union was Tito's decision to begin large-scale repression against enemies of the government. This repression was not limited to known and alleged Stalinists but also included members of the Communist Party or anyone exhibiting sympathy towards the Soviet Union. Prominent partisans, such as Vlado Dapčević and Dragoljub Mićunović, were victims of this period of strong repression, which lasted until 1956 and was marked by significant violations of human rights. Tens of thousands of political opponents served in forced labour camps, such as Goli Otok (meaning Barren Island), and hundreds died. An often disputed but relatively feasible number that was put forth by the Yugoslav government itself in 1964 places the number of Goli Otok inmates incarcerated between 1948 and 1956 to be 16,554, with less than 600 having died during detention. The facilities at Goli Otok were abandoned in 1956, and jurisdiction of the now-defunct political prison was handed over to the government of the Socialist Republic of Croatia.

Tito's estrangement from the USSR enabled Yugoslavia to obtain U.S. aid via the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), the same U.S. aid institution that administered the Marshall Plan. Still, Tito did not agree to align with the West, which was a common consequence of accepting American aid at the time. After Stalin's death in 1953, relations with the USSR were relaxed, and Tito began to receive aid from the Comecon as well. In this way, Tito played East–West antagonism to his advantage. Instead of choosing sides, he was instrumental in kick-starting the

Tito's estrangement from the USSR enabled Yugoslavia to obtain U.S. aid via the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), the same U.S. aid institution that administered the Marshall Plan. Still, Tito did not agree to align with the West, which was a common consequence of accepting American aid at the time. After Stalin's death in 1953, relations with the USSR were relaxed, and Tito began to receive aid from the Comecon as well. In this way, Tito played East–West antagonism to his advantage. Instead of choosing sides, he was instrumental in kick-starting the  On 26 June 1950, the Parliament of Yugoslavia, National Assembly supported a crucial bill written by

On 26 June 1950, the Parliament of Yugoslavia, National Assembly supported a crucial bill written by

Under Tito's leadership, Yugoslavia became a founding member of the

Under Tito's leadership, Yugoslavia became a founding member of the  In the early 1950s, Yugoslav-Hungarian relations were strained as Tito made little secret of his distaste for the Stalinist Mátyás Rákosi and his preference for the "national communist" Imre Nagy instead. Tito's decision to create a "Balkan Pact (1953), Balkan Pact" by signing a treaty of alliance with NATO members Turkey and Greece in 1954 was regarded as tantamount to joining NATO in Soviet eyes, and his vague talk of a neutralist Communist federation of Eastern European states was seen as a major threat in Moscow. The Embassy of Serbia, Budapest, Yugoslav embassy in Budapest was seen by the Soviets as a centre of subversion in Hungary as they accused Yugoslav diplomats and journalists, sometimes with justification, of supporting Nagy. However, when the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, revolt broke out in Hungary in October 1956, Tito accused Nagy of losing control of the situation, as he wanted a Communist Hungary independent of the Soviet Union, not the overthrow of Hungarian communism. On 31 October 1956, Tito ordered the Yugoslav media to stop praising Nagy and he quietly supported the Soviet intervention on 4 November to end the revolt in Hungary, as he believed that a Hungary ruled by anti-communists would pursue irredentist claims against Yugoslavia, as had just been the case during the interwar period. To escape from the Soviets, Nagy fled to the Yugoslav embassy, where Tito granted him asylum. On 5 November 1956, Soviet tanks shelled the Yugoslav embassy in Budapest, killing the Yugoslav cultural attache and several other diplomats. Tito's refusal to turn over Nagy, despite increasingly shrill Soviet demands that he do so, served his purposes well with relations with the Western states, as he was presented in the Western media as the "good communist" who stood up to Moscow by sheltering Nagy and the other Hungarian leaders. On 22 November, Nagy and his cabinet left the embassy on a bus that took them into exile in Yugoslavia after the new Hungarian leader, János Kádár had promised Tito in writing that they would not be harmed. Much to Tito's fury, when the bus left the Yugoslav embassy, it was promptly boarded by KGB agents who arrested the Hungarian leaders and roughly handled the Yugoslav diplomats who tried to protect them. Nagy's kidnapping, followed by his execution, almost led Yugoslavia to break off diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, and in 1957 Tito boycotted the ceremonials in Moscow for the 40th October Revolution Day, anniversary of the October Revolution, the only communist leader who did not attend.

Yugoslavia had a liberal travel policy permitting foreigners to freely travel through the country and its citizens to travel worldwide, whereas it was limited by most Communist countries. A number of Yugoslav citizens worked throughout Western Europe. Tito met many world leaders during his rule, such as Soviet rulers

In the early 1950s, Yugoslav-Hungarian relations were strained as Tito made little secret of his distaste for the Stalinist Mátyás Rákosi and his preference for the "national communist" Imre Nagy instead. Tito's decision to create a "Balkan Pact (1953), Balkan Pact" by signing a treaty of alliance with NATO members Turkey and Greece in 1954 was regarded as tantamount to joining NATO in Soviet eyes, and his vague talk of a neutralist Communist federation of Eastern European states was seen as a major threat in Moscow. The Embassy of Serbia, Budapest, Yugoslav embassy in Budapest was seen by the Soviets as a centre of subversion in Hungary as they accused Yugoslav diplomats and journalists, sometimes with justification, of supporting Nagy. However, when the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, revolt broke out in Hungary in October 1956, Tito accused Nagy of losing control of the situation, as he wanted a Communist Hungary independent of the Soviet Union, not the overthrow of Hungarian communism. On 31 October 1956, Tito ordered the Yugoslav media to stop praising Nagy and he quietly supported the Soviet intervention on 4 November to end the revolt in Hungary, as he believed that a Hungary ruled by anti-communists would pursue irredentist claims against Yugoslavia, as had just been the case during the interwar period. To escape from the Soviets, Nagy fled to the Yugoslav embassy, where Tito granted him asylum. On 5 November 1956, Soviet tanks shelled the Yugoslav embassy in Budapest, killing the Yugoslav cultural attache and several other diplomats. Tito's refusal to turn over Nagy, despite increasingly shrill Soviet demands that he do so, served his purposes well with relations with the Western states, as he was presented in the Western media as the "good communist" who stood up to Moscow by sheltering Nagy and the other Hungarian leaders. On 22 November, Nagy and his cabinet left the embassy on a bus that took them into exile in Yugoslavia after the new Hungarian leader, János Kádár had promised Tito in writing that they would not be harmed. Much to Tito's fury, when the bus left the Yugoslav embassy, it was promptly boarded by KGB agents who arrested the Hungarian leaders and roughly handled the Yugoslav diplomats who tried to protect them. Nagy's kidnapping, followed by his execution, almost led Yugoslavia to break off diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, and in 1957 Tito boycotted the ceremonials in Moscow for the 40th October Revolution Day, anniversary of the October Revolution, the only communist leader who did not attend.

Yugoslavia had a liberal travel policy permitting foreigners to freely travel through the country and its citizens to travel worldwide, whereas it was limited by most Communist countries. A number of Yugoslav citizens worked throughout Western Europe. Tito met many world leaders during his rule, such as Soviet rulers  Thousands of Yugoslav military advisors travelled to Guinea after its decolonisation and as the French government tried to destabilise the country. Tito also covertly helped left-wing liberation movements to destabilise the Portuguese colonial empire. He saw the murder of Patrice Lumumba in 1961 as the "greatest crime in contemporary history". The country's military academies hosted left-wing activists from SWAPO (Namibia) and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (South Africa) as part of Tito's efforts to undermine apartheid in South Africa. In 1980, the intelligence services of South Africa and Argentina plotted to return the 'favour' by covertly bringing 1,500 anti-urban communist guerrillas to Yugoslavia. The operation was aimed at overthrowing Tito and was planned during the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow so that the Soviets would be too busy to react. The operation was finally abandoned due to Tito's death.

In 1953, Tito travelled to Britain for a state visit and met with Winston Churchill. He also toured Cambridge and visited the University Library.

Tito visited India from 22 December 1954 to 8 January 1955. After his return, he removed many restrictions on Yugoslavia's churches and spiritual institutions.

Thousands of Yugoslav military advisors travelled to Guinea after its decolonisation and as the French government tried to destabilise the country. Tito also covertly helped left-wing liberation movements to destabilise the Portuguese colonial empire. He saw the murder of Patrice Lumumba in 1961 as the "greatest crime in contemporary history". The country's military academies hosted left-wing activists from SWAPO (Namibia) and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (South Africa) as part of Tito's efforts to undermine apartheid in South Africa. In 1980, the intelligence services of South Africa and Argentina plotted to return the 'favour' by covertly bringing 1,500 anti-urban communist guerrillas to Yugoslavia. The operation was aimed at overthrowing Tito and was planned during the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow so that the Soviets would be too busy to react. The operation was finally abandoned due to Tito's death.

In 1953, Tito travelled to Britain for a state visit and met with Winston Churchill. He also toured Cambridge and visited the University Library.

Tito visited India from 22 December 1954 to 8 January 1955. After his return, he removed many restrictions on Yugoslavia's churches and spiritual institutions.

Tito also developed warm relations with Burma under U Nu, travelling to the country in 1955 and again in 1959, though he did not receive the same treatment in 1959 from the new leader, Ne Win. Tito had an especially close friendship with Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, who preached an eccentric mixture of monarchism, Buddhism and socialism, and, like Tito, wanted his country to be neutral in the Cold War. Tito saw Sihanouk as something of a kindred soul who, like him, had to struggle to maintain his backward country's neutrality in the face of rival power blocs. By contrast, Tito strongly disliked President Idi Amin of Uganda, whom he saw as thuggish and possibly insane.

Because of its neutrality, Yugoslavia was often rare among Communist countries in having diplomatic relations with right-wing, anti-communist governments. For example, Yugoslavia was the only communist country that had diplomatic relations with Alfredo Stroessner's Paraguay. Yugoslavia went on to sell arms to the staunchly anti-communist regime of Guatemala under Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García during the Guatemalan Civil War. Notable exceptions to Yugoslavia's neutral stance toward anti-communist countries include Spain under Franco, Greek junta, Greece under Greek junta, and Chile under Pinochet; Yugoslavia was one of many countries that severed diplomatic relations with Chile after 1973 Chilean coup d'état, Salvador Allende was overthrown.

Tito also developed warm relations with Burma under U Nu, travelling to the country in 1955 and again in 1959, though he did not receive the same treatment in 1959 from the new leader, Ne Win. Tito had an especially close friendship with Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, who preached an eccentric mixture of monarchism, Buddhism and socialism, and, like Tito, wanted his country to be neutral in the Cold War. Tito saw Sihanouk as something of a kindred soul who, like him, had to struggle to maintain his backward country's neutrality in the face of rival power blocs. By contrast, Tito strongly disliked President Idi Amin of Uganda, whom he saw as thuggish and possibly insane.

Because of its neutrality, Yugoslavia was often rare among Communist countries in having diplomatic relations with right-wing, anti-communist governments. For example, Yugoslavia was the only communist country that had diplomatic relations with Alfredo Stroessner's Paraguay. Yugoslavia went on to sell arms to the staunchly anti-communist regime of Guatemala under Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García during the Guatemalan Civil War. Notable exceptions to Yugoslavia's neutral stance toward anti-communist countries include Spain under Franco, Greek junta, Greece under Greek junta, and Chile under Pinochet; Yugoslavia was one of many countries that severed diplomatic relations with Chile after 1973 Chilean coup d'état, Salvador Allende was overthrown.

Starting in the 1950s, Tito's government permitted Yugoslav workers to go to western Europe, especially West Germany, as ''Gastarbeiter'' ("guest workers"). The exposure of many Yugoslavs to the West and its culture led many Yugoslavians to view themselves as culturally closer to Western Europe than Eastern Europe. In the autumn of 1960, Tito met President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the United Nations General Assembly meeting. They discussed a range of issues from arms control to economic development. When Eisenhower remarked that Yugoslavia's neutrality was "neutral on his side", Tito replied that neutrality did not imply passivity but meant "not taking sides". On 7 April 1963, the country changed its official name from "Federal People's Republic" to "Socialist Federal Republic" of Yugoslavia. Economy of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Economic reforms encouraged Small business, smallscale private enterprise (up to five full-time workers; most of these were family businesses and largest in agriculture) and greatly relaxed restrictions on religious expression. Tito subsequently toured the Americas. In Chile, two government ministers resigned over his visit to that country.

Starting in the 1950s, Tito's government permitted Yugoslav workers to go to western Europe, especially West Germany, as ''Gastarbeiter'' ("guest workers"). The exposure of many Yugoslavs to the West and its culture led many Yugoslavians to view themselves as culturally closer to Western Europe than Eastern Europe. In the autumn of 1960, Tito met President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the United Nations General Assembly meeting. They discussed a range of issues from arms control to economic development. When Eisenhower remarked that Yugoslavia's neutrality was "neutral on his side", Tito replied that neutrality did not imply passivity but meant "not taking sides". On 7 April 1963, the country changed its official name from "Federal People's Republic" to "Socialist Federal Republic" of Yugoslavia. Economy of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Economic reforms encouraged Small business, smallscale private enterprise (up to five full-time workers; most of these were family businesses and largest in agriculture) and greatly relaxed restrictions on religious expression. Tito subsequently toured the Americas. In Chile, two government ministers resigned over his visit to that country.

In 1966, an agreement with the Holy See, fostered in part by the death in 1960 of the anti-communist archbishop of Zagreb Aloysius Stepinac and shifts in the church's approach to resisting communism originating in the Second Vatican Council, accorded new freedom to the Yugoslav Roman Catholic Church, particularly to catechise and open seminaries. The agreement also eased tensions, which had prevented the naming of new bishops in Yugoslavia since 1945. Holy See and Yugoslavia reconciled Holy See–Yugoslavia relations, their relations and worked together on achieving peace in Vietnam. Tito's new socialism met opposition from traditional communists culminating in a conspiracy headed by

In 1966, an agreement with the Holy See, fostered in part by the death in 1960 of the anti-communist archbishop of Zagreb Aloysius Stepinac and shifts in the church's approach to resisting communism originating in the Second Vatican Council, accorded new freedom to the Yugoslav Roman Catholic Church, particularly to catechise and open seminaries. The agreement also eased tensions, which had prevented the naming of new bishops in Yugoslavia since 1945. Holy See and Yugoslavia reconciled Holy See–Yugoslavia relations, their relations and worked together on achieving peace in Vietnam. Tito's new socialism met opposition from traditional communists culminating in a conspiracy headed by

Tito became increasingly ill over the course of 1979. During this time, ''Vila Srna'' was built for his use near Morović in the event of his recovery. On 7 January and again on 12 January 1980, Tito was admitted to the Ljubljana University Medical Centre, Medical Centre in Ljubljana, the capital city of the SR Slovenia, with peripheral vascular disease, circulation problems in his legs. Tito's stubbornness and refusal to allow doctors to follow through with the necessary amputation of his left leg played a part in his eventual death of gangrene-induced infection. His adjutant later testified that Tito threatened to take his own life if his leg was ever amputated and that he had to hide Tito's pistol in fear that he would follow through on his threat. After a private conversation with his sons Žarko and Mišo Broz, he finally agreed, and his left leg was amputated due to arterial blockages. The amputation proved to be too late, and Tito died at the Medical Centre of Ljubljana on 4 May 1980, three days short of his 88th birthday.

The Death and state funeral of Josip Broz Tito, state funeral of Josip Broz Tito drew many world statesmen. It attracted government leaders from 129 states. Based on the number of attending politicians and state delegations, at the time it was the List of largest funerals, largest state funeral in history; this concentration of dignitaries would be unmatched until the List of dignitaries at the funeral of Pope John Paul II, funeral of Pope John Paul II in 2005 and the List of dignitaries at the memorial service of Nelson Mandela, memorial service of Nelson Mandela in 2013. Those who attended included four kings, 31 presidents, six princes, 22 prime ministers, and 47 ministers of foreign affairs. They came from both sides of the Cold War, from 128 countries out of 154 UN members at the time.

Reporting on his death, ''The New York Times'' wrote:

Tito was interred in the House of Flowers (mausoleum), House of Flowers, a mausoleum in Belgrade which forms part of a memorial complex in the grounds of the Museum of Yugoslav History (formerly called "Museum 25 May" and "Museum of the Revolution"). The museum keeps the gifts Tito received during his presidency. The collection includes original prints of ''Los Caprichos'' by Francisco Goya, and many others.

Tito became increasingly ill over the course of 1979. During this time, ''Vila Srna'' was built for his use near Morović in the event of his recovery. On 7 January and again on 12 January 1980, Tito was admitted to the Ljubljana University Medical Centre, Medical Centre in Ljubljana, the capital city of the SR Slovenia, with peripheral vascular disease, circulation problems in his legs. Tito's stubbornness and refusal to allow doctors to follow through with the necessary amputation of his left leg played a part in his eventual death of gangrene-induced infection. His adjutant later testified that Tito threatened to take his own life if his leg was ever amputated and that he had to hide Tito's pistol in fear that he would follow through on his threat. After a private conversation with his sons Žarko and Mišo Broz, he finally agreed, and his left leg was amputated due to arterial blockages. The amputation proved to be too late, and Tito died at the Medical Centre of Ljubljana on 4 May 1980, three days short of his 88th birthday.

The Death and state funeral of Josip Broz Tito, state funeral of Josip Broz Tito drew many world statesmen. It attracted government leaders from 129 states. Based on the number of attending politicians and state delegations, at the time it was the List of largest funerals, largest state funeral in history; this concentration of dignitaries would be unmatched until the List of dignitaries at the funeral of Pope John Paul II, funeral of Pope John Paul II in 2005 and the List of dignitaries at the memorial service of Nelson Mandela, memorial service of Nelson Mandela in 2013. Those who attended included four kings, 31 presidents, six princes, 22 prime ministers, and 47 ministers of foreign affairs. They came from both sides of the Cold War, from 128 countries out of 154 UN members at the time.

Reporting on his death, ''The New York Times'' wrote:

Tito was interred in the House of Flowers (mausoleum), House of Flowers, a mausoleum in Belgrade which forms part of a memorial complex in the grounds of the Museum of Yugoslav History (formerly called "Museum 25 May" and "Museum of the Revolution"). The museum keeps the gifts Tito received during his presidency. The collection includes original prints of ''Los Caprichos'' by Francisco Goya, and many others.

Tito is credited with transforming Yugoslavia from a poor nation to a middle-income one that saw vast improvements in women's rights, health, education, urbanisation, industrialisation, and many other areas of human and economic development. A 2010 poll found that as many as 81% of Serbians believe that life was better under Tito. Tito also ranked first in the "Greatest Croatian" poll which was conducted in 2003 by the Croatian weekly news magazine ''Nacional (weekly), Nacional''.

During his life and especially in the first year after his death, several places were List of places named after Tito, named after Tito; several of these have since returned to their original names.

For example, Podgorica, formerly Titograd (though Podgorica's international airport is still identified by the code TGD), and Užice, formerly known as Titovo Užice, which reverted to its original name in 1992. Streets in Belgrade, the capital, have all reverted to their original pre-World War II and pre-communist names as well. In 2004, Antun Augustinčić's statue of Broz in his birthplace of

Tito is credited with transforming Yugoslavia from a poor nation to a middle-income one that saw vast improvements in women's rights, health, education, urbanisation, industrialisation, and many other areas of human and economic development. A 2010 poll found that as many as 81% of Serbians believe that life was better under Tito. Tito also ranked first in the "Greatest Croatian" poll which was conducted in 2003 by the Croatian weekly news magazine ''Nacional (weekly), Nacional''.

During his life and especially in the first year after his death, several places were List of places named after Tito, named after Tito; several of these have since returned to their original names.

For example, Podgorica, formerly Titograd (though Podgorica's international airport is still identified by the code TGD), and Užice, formerly known as Titovo Užice, which reverted to its original name in 1992. Streets in Belgrade, the capital, have all reverted to their original pre-World War II and pre-communist names as well. In 2004, Antun Augustinčić's statue of Broz in his birthplace of

Tito was married several times and had numerous affairs. In 1918 he was brought to

Tito was married several times and had numerous affairs. In 1918 he was brought to  His best-known wife was Jovanka Broz. Tito was just shy of his 60th birthday and she was 27 when they married in April 1952, with state security chief

His best-known wife was Jovanka Broz. Tito was just shy of his 60th birthday and she was 27 when they married in April 1952, with state security chief  As president, Tito had access to extensive (state-owned) property associated with the office and maintained a lavish lifestyle. In Belgrade, he resided in the official residence, the Beli Dvor, and maintained a separate private home at 10 Užička Street. The Brijuni Islands were the site of the State Summer Residence from 1949 on. The pavilion was designed by Jože Plečnik and included a zoo. Close to 100 foreign heads of state visited Tito at the island residence, along with film stars such as Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Sophia Loren, Carlo Ponti, and Gina Lollobrigida. On the island of Brijuni, a museum displays photos of the many visitors that Tito received over more than three decades.

As president, Tito had access to extensive (state-owned) property associated with the office and maintained a lavish lifestyle. In Belgrade, he resided in the official residence, the Beli Dvor, and maintained a separate private home at 10 Užička Street. The Brijuni Islands were the site of the State Summer Residence from 1949 on. The pavilion was designed by Jože Plečnik and included a zoo. Close to 100 foreign heads of state visited Tito at the island residence, along with film stars such as Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Sophia Loren, Carlo Ponti, and Gina Lollobrigida. On the island of Brijuni, a museum displays photos of the many visitors that Tito received over more than three decades.

Another residence was maintained at Lake Bled, while the grounds at Karađorđevo (Bačka Palanka), Karađorđevo were the site of "diplomatic hunts". By 1974 Tito had at his disposal 32 official residences, large and small, the yacht ''Yugoslav yacht Galeb, Galeb'' ("seagull"), a Boeing 727 as the presidential aeroplane, and the Tito's Blue Train, Blue Train. After his death, the presidential Boeing 727 was sold to Aviogenex, the ''Galeb'' remained docked in Montenegro, and the Blue Train was stored in a Serbian train shed for over two decades. While Tito was the person who held the office of president for by far the longest period, the associated property was not private, and much of it continues to be used by national governments, as public property or for use by high-ranking officials.

Tito claimed to speak

Another residence was maintained at Lake Bled, while the grounds at Karađorđevo (Bačka Palanka), Karađorđevo were the site of "diplomatic hunts". By 1974 Tito had at his disposal 32 official residences, large and small, the yacht ''Yugoslav yacht Galeb, Galeb'' ("seagull"), a Boeing 727 as the presidential aeroplane, and the Tito's Blue Train, Blue Train. After his death, the presidential Boeing 727 was sold to Aviogenex, the ''Galeb'' remained docked in Montenegro, and the Blue Train was stored in a Serbian train shed for over two decades. While Tito was the person who held the office of president for by far the longest period, the associated property was not private, and much of it continues to be used by national governments, as public property or for use by high-ranking officials.

Tito claimed to speak

online

* * Cicic, Ana. "Yugoslavia Revisited: Contested Histories through Public Memories of President Tito." (2020)

online

* Cosovschi, Agustin. "Seeing and Imagining the Land of Tito: Oscar Waiss and the Geography of Socialist Yugoslavia." ''Balkanologie. Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires'' 17.1 (2022)

online

* Foster, Samuel. ''Yugoslavia in the British imagination: Peace, war and peasants before Tito'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021

online

See als

online book review

* Trošt, Tamara P. "The image of Josip Broz Tito in post-Yugoslavia: Between national and local memory." in ''Ruler Personality Cults from Empires to Nation-States and Beyond'' (Routledge, 2020) pp. 143–162

online

at marxists.org * Josip Broz Tito

''The Yugoslav peoples fight to live''

1944. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Broz Tito, Josip Josip Broz Tito, 1892 births 1980 deaths 20th-century presidents in Europe Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war in World War I Croatian communists Yugoslav communists Croatian Marxists Yugoslav Marxists Yugoslav nationalists Yugoslav atheists Yugoslav escapees Yugoslav Partisans members Croatian people of World War II Yugoslav people of World War II Croatian politicians Yugoslav politicians Croatian people of Slovenian descent Croatian revolutionaries Secretaries-general of the Non-Aligned Movement League of Communists of Yugoslavia politicians Members of the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia Members of the Politburo of the 5th Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia Members of the Executive Committee of the 6th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Executive Committee of the 7th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Presidency of the 8th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Ex officio members of the Presidency of the 9th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Ex officio members of the Presidency of the 10th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Ex officio members of the Presidency of the 11th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Executive Bureau of the Presidency of the 9th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Central Committee of the 4th Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia Members of the Central Committee of the 5th Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia Members of the Central Committee of the 6th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Central Committee of the 7th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Central Committee of the 8th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Central Committee of the 10th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Members of the Central Committee of the 11th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia Marshals Yugoslav Comintern people People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from Kumrovec Presidents for life People of the Russian Civil War Old Bolsheviks Presidents of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia World War I prisoners of war held by Russia World War II political leaders Yugoslav soldiers Anti-Stalinist left People of the Cold War Escapees from Russian detention Foreign recipients of the Nishan-e-Pakistan Grand Crosses of the Order of Polonia Restituta Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion Heroes of the Republic (North Korea) Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Recipients of the Collar of Honour Recipients of the Military Order of the White Lion Recipients of the Order of the Cross of Grunwald, 1st class Recipients of the Order of the Hero of Socialist Labour Recipients of the Order of Karl Marx Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the October Revolution Recipients of the Order of the People's Hero Recipients of the Order of the Pioneers of Liberia Recipients of the Order of Suvorov, 1st class Recipients of the Order of Victory Recipients of the Virtuti Militari Deaths from gangrene

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he led the Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, and Slovene language, Slovene: , officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odr ...

, often regarded as the most effective resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

in German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly military occupation, militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the governmen ...

. Following Yugoslavia's liberation in 1945, he served as its prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

from 1945 to 1963, and president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

from 1953 until his death in 1980. The political ideology and policies promulgated by Tito are known as Titoism

Titoism is a Types of socialism, socialist political philosophy most closely associated with Josip Broz Tito and refers to the ideology and policies of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY) during the Cold War. It is characterized by a br ...

.

Tito was born to a Croat father and a Slovene mother in Kumrovec

Kumrovec () is a village in the northern part Croatia, part of Krapina-Zagorje County. It sits on the Sutla River, along the Croatian-Slovenian border. The Kumrovec municipality has 1,413 residents (2021), but the village itself has only 267 peo ...

in what was then Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. Drafted into military service, he distinguished himself, becoming the youngest sergeant major

Sergeant major is a senior Non-commissioned officer, non-commissioned Military rank, rank or appointment in many militaries around the world.

History

In 16th century Spain, the ("sergeant major") was a general officer. He commanded an army's ...

in the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army, also known as the Imperial and Royal Army,; was the principal ground force of Austria-Hungary from 1867 to 1918. It consisted of three organisations: the Common Army (, recruited from all parts of Austria-Hungary), ...

of that time. After being seriously wounded and captured by the Russians during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, he was sent to a work camp in the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

. Tito participated in some events of the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

in 1917 and the subsequent Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. Upon his return to the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

in 1920, he entered the newly established Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast Europe, Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () h ...

, where he joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia, known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, was the founding and ruling party of SFR Yugoslavia. It was formed in 1919 as the main communist opposition party in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats a ...

. Having assumed de facto control over the party by 1937, Tito was formally elected its general secretary in 1939 and later its president, the title he held until his death. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, after the Nazi invasion of the area, he led the Yugoslav guerrilla movement, the Partisans

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Itali ...

(1941–1945). By the end of the war, the Partisans, with the Allies' backing since mid-1943, took power in Yugoslavia.

After the war, Tito served as the prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

(1945–1963), president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

(1953–1980; from 1974 president for life), and marshal of Yugoslavia

Marshal of Yugoslavia was the highest military distinction, rather than a military rank of the Yugoslav People's Army. In military hierarchy it was equivalent to Marshal#Military, Marshal (field marshal), and, simultaneously, a Socialist Federal R ...

, the highest rank of the Yugoslav People's Army

The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA/; Macedonian language, Macedonian, Montenegrin language, Montenegrin and sr-Cyrl-Latn, Југословенска народна армија, Jugoslovenska narodna armija; Croatian language, Croatian and ; , J ...

(JNA). In 1945, under his leadership, Yugoslavia became a communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

, which was eventually renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), known from 1945 to 1963 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country ...

. Despite being one of the founders of the Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist–Leninist communist parties in Europe which existed from 1947 to 1956. Formed in the wake of the dissolution ...

, he became the first Cominform member and the only leader in Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's lifetime to defy Soviet hegemony in the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

, leading to Yugoslavia's expulsion from the organisation in 1948 in what was known as the Tito–Stalin split

The Tito–Stalin split or the Soviet–Yugoslav split was the culmination of a conflict between the political leaderships of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, under Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin, respectively, in the years following World W ...

. In the following years, alongside other political leaders and Marxist theorists such as Edvard Kardelj

Edvard Kardelj (; 27 January 1910 – 10 February 1979), also known by the pseudonyms Bevc, Sperans, and Krištof, was a Yugoslav politician and economist. He was one of the leading members of the Communist Party of Slovenia before World War II ...

and Milovan Đilas

Milovan Djilas (; sr-Cyrl-Latn, Милован Ђилас, Milovan Đilas, ; 12 June 1911 – 20 April 1995) was a Yugoslav communist politician, theorist and author. He was a key figure in the Partisan movement during World War II, as well ...

, he initiated the idiosyncratic model of socialist self-management

Socialist self-management or self-governing socialism was a form of workers' self-management used as a social and economic model formulated by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. It was instituted by law in 1950 and lasted in the Socialist ...

in which firms were managed by workers' council

A workers' council, also called labour council, is a type of council in a workplace or a locality made up of workers or of temporary and instantly revocable delegates elected by the workers in a locality's workplaces. In such a system of polit ...

s and all workers were entitled to workplace democracy

Workplace democracy is the application of democracy in various forms to the workplace, such as voting systems, consensus, debates, democratic structuring, due process, adversarial process, and systems of appeal. It can be implemented in a ...

and equal share of profits

Profit sharing refers to various incentive plans introduced by businesses which provide direct or indirect payments to employees, often depending on the company's profitability, employees' regular salaries, and bonuses. In publicly traded compani ...

. Tito wavered between supporting a centralised or more decentralised federation and ended up favouring the latter to keep ethnic tension

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's position within so ...

s under control; thus, the constitution was gradually developed to delegate as much power as possible to each republic in keeping with the Marxist theory of withering away of the state

The withering away of the state is a Marxist concept coined by Friedrich Engels referring to the expectation that, with the realization of socialism, the state will eventually become obsolete and cease to exist as society will be able to gover ...

. He envisaged the SFR of Yugoslavia as a "federal republic of equal nations and nationalities, freely united on the principle of brotherhood and unity

Brotherhood and unity was a popular slogan of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia that was coined during the Yugoslav People's Liberation War (1941–45), and which evolved into a guiding principle of Yugoslavia's post-war inter-ethnic policy. ...

in achieving specific and common interest." A very powerful cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

arose around him, which the League of Communists of Yugoslavia maintained even after his death. After Tito's death, Yugoslavia's leadership was transformed into an annually rotating presidency to give representation to all of its nationalities and prevent the emergence of an authoritarian leader. Twelve years later, as communism collapsed in Eastern Europe and ethnic tensions escalated, Yugoslavia dissolved and descended into a series of interethnic wars.

Historians critical of Tito view his presidency as authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

and see him as a dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute Power (social and political), power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a polity. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to r ...

, while others characterise him as a benevolent dictator. He was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, and remains popular in the former countries of Yugoslavia. Tito was viewed as a unifying symbol, with his internal policies maintaining the peaceful coexistence of the nations of the Yugoslav federation. He gained further international attention as a co-founder of the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

, alongside Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

of India, Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

of Egypt, Kwame Nkrumah

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (, 21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast (British colony), Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it gained ...

of Ghana, and Sukarno

Sukarno (6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of the Indonesian struggle for independenc ...

of Indonesia. With a highly favourable reputation abroad in both Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

blocs, he received a total of 98 foreign decorations, including the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

and the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

.

Early life

Pre-World War I

Josip Broz was born on 7 May 1892 inKumrovec

Kumrovec () is a village in the northern part Croatia, part of Krapina-Zagorje County. It sits on the Sutla River, along the Croatian-Slovenian border. The Kumrovec municipality has 1,413 residents (2021), but the village itself has only 267 peo ...

, a village in the northern Croatian region of Zagorje

Hrvatsko Zagorje (; Croatian Zagorje; ''zagorje'' is Croatian language, Croatian for 'backland' or 'behind the hills') is a cultural region in northern Croatia, traditionally separated from the country's capital Zagreb by the Medvednica mount ...

. At the time it was part of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia (; or ; ) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was created in 1868 by merging the kingdoms of Kingdom of Croatia (Habs ...

within the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

. He was the seventh or eighth child of Franjo Broz and Marija née Javeršek. His parents had already had a number of children die in early infancy. Broz was christened and raised as a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

. His father, Franjo, was a Croat

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

whose family had lived in the village for three centuries, while his mother, Marija, was a Slovene from the village of Podsreda

Podsreda (; ) is a village in the Municipality of Kozje in eastern Slovenia. It is located near the Croatian border, in the traditional region of Styria. It is known for its market, which takes place every Sunday, and for Podsreda Castle, locate ...

. The villages were apart, and his parents had married on 21 January 1881. Franjo Broz had inherited a estate and a good house, but he was unable to make a success of farming. Josip spent a significant proportion of his pre-school years living with his maternal grandparents at Podsreda, where he became a favourite of his grandfather Martin Javeršek. By the time he returned to Kumrovec to begin school, he spoke Slovene better than Croatian, and had learned to play the piano. Despite his mixed parentage, Broz identified as a Croat like his father and neighbours.

In July 1900, at age eight, Broz entered primary school at Kumrovec. He completed four years of school, failing 2nd grade and graduating in 1905. As a result of his limited schooling, throughout his life, Tito was poor at spelling. After leaving school, he initially worked for a maternal uncle and then on his parents' family farm. In 1907, his father wanted him to emigrate to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

but could not raise the money for the voyage.

Instead, aged 15 years, Broz left Kumrovec and travelled about south to Sisak

Sisak (; also known by other alternative names) is a city in central Croatia, spanning the confluence of the Kupa, Sava and Odra rivers, southeast of the Croatian capital Zagreb, and is usually considered to be where the Posavina (Sava basin ...

, where his cousin Jurica Broz was doing army service. Jurica helped him get a job in a restaurant, but Broz soon got tired of that work. He approached a Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

locksmith

Locksmithing is the work of creating and bypassing locks. Locksmithing is a traditional trade and in many countries requires completion of an apprenticeship. The level of formal education legally required varies by country, ranging from no formal ...

, Nikola Karas, for a three-year apprenticeship, which included training, food, and room and board

Room and board describes an accommodation which, in exchange for money, labour or other recompense, a person is provided with a place to live in addition to meals. It commonly occurs as a fee at higher educational institutions, such as colleges ...

. As his father could not afford to pay for his work clothing, Broz paid for it himself. Soon after, his younger brother Stjepan also became apprenticed to Karas.

During his apprenticeship, Broz was encouraged to mark May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the Northern Hemisphere's March equinox, spring equinox and midsummer June solstice, solstice. Festivities ma ...

in 1909, and he read and sold ''Slobodna Reč'' (), a socialist newspaper. After completing his apprenticeship in September 1910, Broz used his contacts to gain employment in Zagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

. At age 18, he joined the Metal Workers' Union and participated in his first labour protest. He also joined the Social Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia

The Social Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia ( or 'SDSHiS') was a social-democratic political party in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. The party was active from 1894 until 1916.

History

The Social Democratic Party of Hungary, founded in ...

.

He returned home in December 1910. In early 1911, he began a series of moves in search of work, first in Ljubljana

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Ljubljana

, official_name =

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = {{multiple image

, border = infobox

, perrow = 1/2/2/1

, total_widt ...

, then Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

, Kumrovec and Zagreb, where he worked repairing bicycles. He joined his first strike action on May Day 1911. After a brief period of work in Ljubljana, between May 1911 and May 1912, he worked in a factory in Kamnik

Kamnik (; ''Leksikon občin kraljestev in dežel zastopanih v državnem zboru,'' vol. 6: ''Kranjsko''. 1906. Vienna: C. Kr. Dvorna in Državna Tiskarna, pp. 26–27. or ''Stein in Oberkrain'') is the ninth-largest town of Slovenia, located in t ...

in the Kamnik–Savinja Alps

The Kamnik–Savinja Alps () are a mountain range of the Southern Limestone Alps. They lie in northern Slovenia, except for the northernmost part, which lies in Austria.

The western part of the range was named the Kamnik Alps () in 1778 by the sc ...

. After it closed, he was offered redeployment to Čenkov

Čenkov is a municipality and village in Příbram District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The co ...

in Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

. On arriving at his new workplace, he discovered that the employer was trying to bring in cheaper labour to replace the local Czech workers, and he and others joined successful strike action to force the employer to back down.

Driven by curiosity, Broz moved to Plzeň

Plzeň (), also known in English and German as Pilsen (), is a city in the Czech Republic. It is the Statutory city (Czech Republic), fourth most populous city in the Czech Republic with about 188,000 inhabitants. It is located about west of P ...

, where he was briefly employed at the Škoda Works

The Škoda Works (, ) was one of the largest European industrial conglomerates of the 20th century. In 1859, Czech engineer Emil Škoda bought a foundry and machine factory in Plzeň, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary that had been established ten ye ...

. He next travelled to Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

in Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

. He also worked at the Benz car factory in Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (), is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, second-largest city in Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, the States of Ger ...

and visited the Ruhr

The Ruhr ( ; , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr Area, sometimes Ruhr District, Ruhr Region, or Ruhr Valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 1,160/km2 and a populati ...

industrial region. By October 1912, he had reached Vienna. He stayed with his older brother Martin and his family and worked at the Griedl Works before getting a job at Wiener Neustadt

Wiener Neustadt (; Lower_Austria.html" ;"title=".e. Lower Austria">.e. Lower Austria , ) is a city located south of Vienna, in the state of Lower Austria, in northeast Austria. It is a self-governed city and the seat of the district administr ...

. There he worked for Austro-Daimler

Austro-Daimler was an Austrian car manufacturer from 1899 until 1934. It was a subsidiary of the Germany, German ''Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft'' (DMG) until 1909.

History

In 1890, Eduard Bierenz was appointed as Austrian retailer. The company so ...

and was often asked to drive and test the cars. During this time, he spent considerable time fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

and dancing, and during his training and early work life, he also learned German and passable Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

.

World War I

In May 1913, Broz wasconscript

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

ed into the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army, also known as the Imperial and Royal Army,; was the principal ground force of Austria-Hungary from 1867 to 1918. It consisted of three organisations: the Common Army (, recruited from all parts of Austria-Hungary), ...

for his compulsory two years of service. He successfully requested to serve with the 25th Croatian Home Guard Regiment garrisoned in Zagreb. After learning to ski during the winter of 1913 and 1914, Broz was sent to a school for non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is an enlisted rank, enlisted leader, petty officer, or in some cases warrant officer, who does not hold a Commission (document), commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority b ...

s (NCO) in Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

, after which he was promoted to sergeant major

Sergeant major is a senior Non-commissioned officer, non-commissioned Military rank, rank or appointment in many militaries around the world.

History

In 16th century Spain, the ("sergeant major") was a general officer. He commanded an army's ...

. At age 22, he was the youngest of that rank in his regiment. At least one source states that he was the youngest sergeant major in the Austro-Hungarian Army. After winning the regimental fencing competition, Broz came in second in the army fencing championships in Budapest in May 1914.

Soon after the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914, the 25th Croatian Home Guard Regiment marched toward the Serbian

Serbian may refer to:

* Pertaining to Serbia in Southeast Europe; in particular

**Serbs, a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans

** Serbian language

** Serbian culture

**Demographics of Serbia, includes other ethnic groups within the co ...

border. Broz was arrested for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech or organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

and imprisoned in the Petrovaradin fortress

Petrovaradin Fortress ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Петроварадинска тврђава, Petrovaradinska tvrđava, ; ), nicknamed "Gibraltar on/of the Danube", is a Bastion fort, bastion fortress in the town of Petrovaradin, itself part of the City of ...

in present-day Novi Sad

Novi Sad ( sr-Cyrl, Нови Сад, ; #Name, see below for other names) is the List of cities in Serbia, second largest city in Serbia and the capital of the autonomous province of Vojvodina. It is located in the southern portion of the Pannoni ...

. He later gave conflicting accounts of this arrest, telling one biographer that he had threatened to desert to the Russian side but also claiming that the whole matter arose from a clerical error. A third version was that he had been overheard saying that he hoped the Austro-Hungarian Empire would be defeated. After his acquittal and release, his regiment served briefly on the Serbian Front before being deployed to the Eastern Front in Galicia in early 1915 to fight against Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. In his account of his military service, Broz did not mention that he participated in the failed Austrian invasion of Serbia, instead giving the misleading impression that he fought only in Galicia, as it would have offended Serbian opinion to know that he fought in 1914 for the Habsburgs against them. On one occasion, the scout

Scout may refer to:

Youth movement

*Scout (Scouting), a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement

** Scouts (The Scout Association), section for 10-14 year olds in the United Kingdom

** Scouts BSA, sect ...

platoon

A platoon is a Military organization, military unit typically composed of two to four squads, Section (military unit), sections, or patrols. Platoon organization varies depending on the country and the Military branch, branch, but a platoon can ...

he commanded went behind the enemy lines and captured 80 Russian soldiers, bringing them back to their own lines alive. In 1980 it was discovered that Broz had been recommended for an award for gallantry and initiative in reconnaissance and capturing prisoners. Tito's biographer Richard West wrote that Tito actually downplayed his military record as the Austrian Army records showed that he was a brave soldier, which contradicted his later claim to have opposed the Habsburg monarchy and his self-portrait of himself as an unwilling conscript fighting in a war he opposed. Broz's fellow soldiers regarded him as ''kaisertreu'' ("true to the Emperor").

On 25 March 1915, Broz was wounded in the back by a Circassia

Circassia ( ), also known as Zichia, was a country and a historical region in . It spanned the western coastal portions of the North Caucasus, along the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. Circassia was conquered by the Russian Empire during ...

n cavalryman's lance and captured during a Russian attack near Bukovina

Bukovina or ; ; ; ; , ; see also other languages. is a historical region at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. It is located on the northern slopes of the central Eastern Carpathians and the adjoining plains, today divided betwe ...

. In his account of his capture, Broz wrote: "suddenly the right flank yielded and through the gap poured cavalry of the Circassians, from Asiatic Russia. Before we knew it they were thundering through our positions, leaping from their horses and throwing themselves into our trenches with lances lowered. One of them rammed his two-yard, iron-tipped, double-pronged lance into my back just below the left arm. I fainted. Then, as I learned, the Circassians began to butcher the wounded, even slashing them with their knives. Fortunately, Russian infantry reached the positions and put an end to the orgy". Now a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

(POW), Broz was transported east to a hospital established in an old monastery in the town of Sviyazhsk

Sviyazhsk (; ) is a rural locality (a '' selo'') in the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia, located at the confluence of the Volga and Sviyaga Rivers. It is often referred to as an island since the 1955 construction of the Kuybyshev Reservoir downstr ...

on the Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

river near Kazan

Kazan; , IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzanis the largest city and capital city, capital of Tatarstan, Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka (river), Kazanka Rivers, covering an area of , with a population of over 1. ...

. During his 13 months in hospital, he had bouts of pneumonia and typhus, and learned Russian with the help of two schoolgirls who brought him Russian classics by such authors as Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

and Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poe ...

.

After recuperating, in mid-1916, Broz was transferred to the Ardatov POW camp in the Samara Governorate

Samara Governorate () was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire and the Russian SFSR, located in the Volga Region. It existed from 1850 to 1928; its capital was in Samara

Samara, formerly known as Kuybyshev ...

, where he used his skills to maintain the nearby village grain mill. At the end of the year, he was transferred to the Kungur

Kungur () is a town in the southeast of Perm Krai, Russia, located in the Ural Mountains at the confluence of the rivers Iren and Shakva with the Sylva ( Kama's basin). Population: 62,173 ( 2023 Estimate).

History

Kungur was founded ...

POW camp near Perm

Perm or PERM may refer to:

Places

* Perm, Russia, a city in Russia

**Permsky District, the district

**Perm Krai, a federal subject of Russia since 2005

**Perm Oblast, a former federal subject of Russia 1938–2005

** Perm Governorate, an administr ...

where the POWs were used as labour to maintain the newly completed Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway, historically known as the Great Siberian Route and often shortened to Transsib, is a large railway system that connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway ...

. Broz was appointed to be in charge of all the POWs in the camp. During this time, he became aware that camp staff were stealing the Red Cross parcel

Red Cross parcel refers to packages containing mostly food, tobacco and personal hygiene items sent by the International Association of the Red Cross to prisoners of war (POWs) during the First and Second World Wars, as well as at other times ...

s sent to the POWs. When he complained, he was beaten and imprisoned. During the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

, a crowd broke into the prison and returned Broz to the POW camp. A Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

he had met while working on the railway told Broz that his son was working in engineering works in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...