Thus Spoke Zarathustra on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None'' (), also translated as ''Thus Spake Zarathustra'', is a work of philosophical fiction written by German philosopher

Nietzsche was born into, and largely remained within, the Bildungsbürgertum, a sort of highly cultivated middle class. By the time he was a teenager, he had been writing music and poetry. His aunt Rosalie gave him a biography of

Nietzsche was born into, and largely remained within, the Bildungsbürgertum, a sort of highly cultivated middle class. By the time he was a teenager, he had been writing music and poetry. His aunt Rosalie gave him a biography of

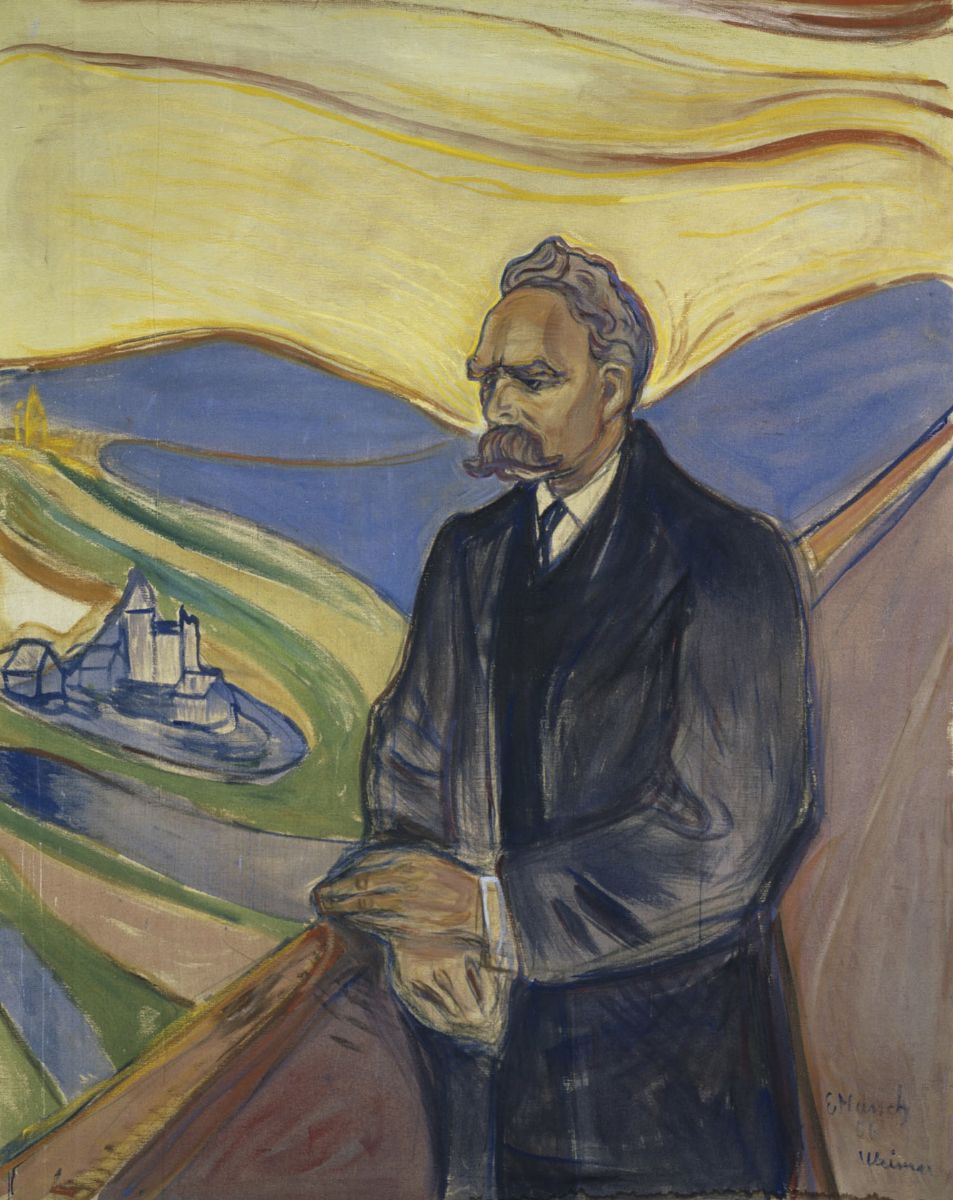

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

; it was published in four volumes between 1883 and 1885. The protagonist is nominally the historical Zarathustra, more commonly called Zoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

in the West.

Much of the book consists of discourses by Zarathustra on a wide variety of subjects, most of which end with the refrain "thus spoke Zarathustra". The character of Zarathustra first appeared in Nietzsche's earlier book '' The Gay Science'' (at §342, which closely resembles §1 of "Zarathustra's Prologue" in ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'').

The style of Nietzsche's ''Zarathustra'' has facilitated varied and often incompatible ideas about what Nietzsche's Zarathustra says. The " planations and claims" given by the character of Zarathustra in this work "are almost always analogical and figurative".Del Caro and Pippin, "Introduction" in ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', Cambridge, 2006. Though there is no consensus about what Zarathustra ''means'' when he speaks, there is some consensus ''about'' that which he speaks. ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' deals with ideas about the ''Übermensch

The ( , ; 'Overman' or 'Superman') is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. In his 1883 book, '' Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' (), Nietzsche has his character Zarathustra posit the as a goal for humanity to set for itself. The repre ...

'', the death of God, the will to power

The will to power () is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's ...

, and eternal recurrence.

Origins

Nietzsche was born into, and largely remained within, the Bildungsbürgertum, a sort of highly cultivated middle class. By the time he was a teenager, he had been writing music and poetry. His aunt Rosalie gave him a biography of

Nietzsche was born into, and largely remained within, the Bildungsbürgertum, a sort of highly cultivated middle class. By the time he was a teenager, he had been writing music and poetry. His aunt Rosalie gave him a biography of Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, natural history, naturalist, List of explorers, explorer, and proponent of Romanticism, Romantic philosophy and Romanticism ...

for his 15th birthday, and reading this inspired a love of learning "for its own sake". The schools he attended, the books he read, and his general milieu fostered and inculcated his interests in Bildung

(, "education", "formation", etc.) refers to the German tradition of self-cultivation (as related to the German for: creation, image, shape), wherein philosophy and education are linked in a manner that refers to a process of both personal an ...

, a concept at least tangential to many in ''Zarathustra'', and he worked extremely hard. He became an outstanding philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also defined as the study of ...

almost accidentally, and he renounced his ideas about being an artist. As a philologist he became particularly sensitive to the transmissions and modifications of ideas, which also bears relevance into ''Zarathustra''. Nietzsche's growing distaste toward philology, however, was yoked with his growing taste toward philosophy. As a student, this yoke was his work with Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek phi ...

. Even with that work he strongly opposed received opinion. With subsequent and properly philosophical work he continued to oppose received opinion.Hollingdale, "Introduction" in ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', Penguin His books leading up to ''Zarathustra'' have been described as nihilistic destruction. Such nihilistic destruction combined with his increasing isolation and the rejection of his marriage proposals (to Lou Andreas-Salomé

Lou Andreas-Salomé (born either Louise von Salomé or Luíza Gustavovna Salomé or Lioulia von Salomé, ; 12 February 1861 – 5 February 1937) was a Russian-born psychoanalyst and a well-traveled author, narrator, and essayist from a French Hu ...

) devastated him. While he was working on ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' he was walking very much. The imagery of his walks mingled with his physical and emotional and intellectual pains and his prior decades of hard work. What "erupted" was ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra''.

Nietzsche has said that the central idea of ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' is the eternal recurrence. He has also said that this central idea first occurred to him in August 1881: he was near a "pyramidal block of stone" while walking through the woods along the shores of Lake Silvaplana in the Upper Engadine, and he made a small note that read "6,000 feet beyond man and time".

A few weeks after meeting this idea, he paraphrased in a notebook something written by Friedrich von Hellwald about Zarathustra.Parkes, "Introduction" in ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', Oxford This paraphrase was developed into the beginning of ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra''.

A year and a half after making that paraphrase, Nietzsche was living in Rapallo

Rapallo ( , , ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, in the Italy, Italian region of Liguria.

As of 2017 it had 29,778 inhabitants. It lies on the Ligurian Sea coast, on the Tigullio Gulf, between Portofino and ...

. Nietzsche claimed that the entire first part was conceived, and that Zarathustra himself "came over him", while walking. He was regularly walking "the magnificent road to Zoagli" and "the whole Bay of Santa Margherita".Nietzsche, cited in Parkes, "Introduction" in ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', Oxford He said in a letter that the entire first part "was conceived in the course of strenuous hiking: absolute certainty, as if every sentence were being called out to me".

Nietzsche returned to "the sacred place" in the summer of 1883 and he "found" the second part.

Nietzsche was in Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one million

According to Nietzsche in ''Ecce Homo'' it was "scarcely one year for the entire work", and ten days each part. More broadly, however, he said in a letter: "The ''whole'' of ''Zarathustra'' is an explosion of forces that have been accumulating for decades".

In January 1884, Nietzsche finished the third part and thought the book finished. But by November he expected a fourth part to be finished by January. He also mentioned a fifth and sixth part leading to Zarathustra's death, "or else he will give me no peace". But after the fourth part was finished he called it "a fourth (and last) part of ''Zarathustra'', a kind of sublime finale, which is not at all meant for the public".

The first three parts were initially published individually and were first published together in a single volume in 1887. The fourth part was written in 1885. While Nietzsche retained mental capacity and was involved in the publication of his works, forty copies of the fourth part were printed at his own expense and distributed to his closest friends, to whom he expressed "a vehement desire never to have the Fourth Part made public". In 1889, however, Nietzsche became significantly incapacitated. In March 1892 part four was published separately, and the following July the four parts were published in a single volume.

Scholars have argued that "the worst possible way to understand Zarathustra is as a teacher of doctrines". Nonetheless ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' "has contributed most to the public perception of Nietzsche as philosophernamely, as the teacher of the 'doctrines' of the

Scholars have argued that "the worst possible way to understand Zarathustra is as a teacher of doctrines". Nonetheless ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' "has contributed most to the public perception of Nietzsche as philosophernamely, as the teacher of the 'doctrines' of the

The title is ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra''. Much of the book is what Zarathustra said. What Zarathustra says Nietzsche would often appropriate masks and models to develop himself and his thoughts and ideas, and to find voices and names through which to communicate. While writing ''Zarathustra'', Nietzsche was particularly influenced by "the language of Luther and the poetic form of the Bible". But ''Zarathustra'' also frequently alludes to or appropriates from Hölderlin's '' Hyperion'' and

Introduction

. In ''Thus spoke Zarathustra''.

Zarathustra-Commentar

' (in German), 4 vols. Leipzig: Haessel. * Zittel, Claus. 2011. ''Das ästhetische Kalkül von Friedrich Nietzsches 'Also sprach Zarathustra. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. . * Schmidt, Rüdiger. "Introduction" (in German). In ''Nietzsche für Anfänger: Also sprach Zarathustra – Eine Lese-Einführung''. * Zittel, Claus: Wer also erzählt Nietzsches Zarathustra?, in: Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 95, (2021), 327–351.

''Also sprach Zarathustra''

at Nietzsche Source

Project Gutenberg's etext of ''Also sprach Zarathustra'' (the German original)

Project Gutenberg's etext of ''Thus Spake Zarathustra'', translated by Thomas Common

* {{Authority control Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1883 German novels,

Character of Zarathustra

In the 1888 ''Ecce '', Nietzsche explains what he meant by making the Persian figure ofZoroaster

Zarathushtra Spitama, more commonly known as Zoroaster or Zarathustra, was an Iranian peoples, Iranian religious reformer who challenged the tenets of the contemporary Ancient Iranian religion, becoming the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism ...

the protagonist of his book:

Thus, " Nietzsche admits himself, by choosing the name of Zarathustra as the prophet of his philosophy in a poetical idiom, he wanted to pay homage to the original Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

prophet as a prominent founding figure of the spiritual-moral phase in human history, and reverse his teachings at the same time, according to his fundamental critical views on morality. The original Zoroastrian world-view interpreted being

Existence is the state of having being or reality in contrast to nonexistence and nonbeing. Existence is often contrasted with essence: the essence of an entity is its essential features or qualities, which can be understood even if one do ...

on the basis of the universality of the moral values and saw the whole world as an arena of the struggle between two fundamental moral elements, Good and Evil, depicted in two antagonistic divine figures nowiki/>Ahura Mazda and Ahriman">Ahura_Mazda.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Ahura Mazda">nowiki/>Ahura Mazda and Ahriman]. Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, in contrast, puts forward his ontological immoralism and tries to prove and reestablish the primordial innocence of beings by destroying philosophically all moralistic interpretations and evaluations of being".

Synopsis

First part

The book begins with a prologue that sets up many of the themes that will be explored throughout the work. Zarathustra is introduced as a hermit who has lived ten years on a mountain with his two companions, an eagle and a serpent. One morning – inspired by the sun, which is happy only when it shines upon others – Zarathustra decides to return to the world and share his wisdom. Upon descending the mountain, he encounters a saint living in a forest, who spends his days praising God. Zarathustra marvels that the saint has not yet heard that " God is dead". Arriving at the nearest town, Zarathustra addresses a crowd which has gathered to watch a tightrope walker. He tells them that mankind's goal must be to create something superior to itself – a new type of human, the ''Übermensch

The ( , ; 'Overman' or 'Superman') is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. In his 1883 book, '' Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' (), Nietzsche has his character Zarathustra posit the as a goal for humanity to set for itself. The repre ...

''. All men, he says, must be prepared to will their own destruction in order to bring the ''Übermensch'' into being. The crowd greets this speech with scorn and mockery, and meanwhile the tightrope show begins. When the rope-dancer is halfway across, a clown comes up behind him, urging him to get out of the way. The clown then leaps over the rope-dancer, causing the latter to fall to his death. The crowd scatters; Zarathustra takes the corpse of the rope-dancer on his shoulders, carries it into the forest, and lays it in a hollow tree. He decides that from this point on, he will no longer attempt to speak to the masses, but only to a few chosen disciples.

There follows a series of discourses in which Zarathustra overturns many of the precepts of Christian morality. He gathers a group of disciples, but ultimately abandons them, saying that he will not return until they have disowned him.

Second part

Zarathustra retires to his mountain cave, and several years pass by. One night, he dreams that he looks into a mirror and sees the face of a devil instead of his own; he takes this as a sign that his doctrines are being distorted by his enemies, and joyfully descends the mountain to recover his lost disciples. More discourses follow, which continue to develop the themes of the death of God and the rise of the ''Übermensch'', and also introduce the concept of thewill to power

The will to power () is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's ...

. There are hints, however, that Zarathustra is holding something back. A series of dreams and visions prompt him to reveal this secret teaching, but he cannot bring himself to do so. He withdraws from his disciples once more, in order to perfect himself.

Third part

While journeying home, Zarathustra is waylaid by the spirit of gravity, a dwarf-like creature which clings to his back and whispers taunts into his ear. Zarathustra at first becomes despondent, but then takes courage; he challenges the spirit to hear the "abysmal thought" which he has so far refrained from speaking. This is the doctrine of eternal recurrence. Time, says Zarathustra, is infinite, stretching both forward and backward into eternity. This means that everything that happens now must have happened before, and that every moment must continue to repeat itself eternally. As he speaks, Zarathustra hears a dog howl in terror, and then he sees a new vision – a shepherd choking on a black serpent which has crept into his throat. At Zarathustra's urging, the shepherd bites the serpent's head off and spits it out. In that moment, the shepherd is transformed into a laughing, radiant being, something greater than human. Zarathustra continues his journey, delivering more discourses inspired by his observations. Arriving at his mountain cave, he remains there for some time, reflecting on his mission. He is disgusted at humanity's pettiness, and despairs at the thought of the eternal recurrence of such an insignificant race. Eventually, however, he discovers his own longing for eternity, and sings a song in celebration of eternal return.Fourth part

Zarathustra begins to grow old as he remains secluded in his cave. One day, he is visited by a soothsayer, who says that he has come to tempt Zarathustra to his final sin – compassion (''mitleiden'', which can also be translated as "pity"). A loud cry of distress is heard, and the soothsayer tells Zarathustra that "the higher man" is calling to him. Zarathustra is alarmed, and rushes to the aid of the higher man. Searching through his domain for the person who uttered the cry for help, Zarathustra encounters a series of characters representative of various aspects of humanity. He engages each of them in conversation, and ends by inviting each one to await his return in his cave. After a day's search, however, he is unable to find the higher man. Returning home, he hears the cry of distress once more, now coming from inside his own cave. He realises that all the people he has spoken to that day are collectively the higher man. Welcoming them to his home, he nevertheless tells them that they are not the men he has been waiting for; they are only the precursors of the ''Übermensch''. Zarathustra hosts a supper for his guests, which is enlivened by songs and arguments, and ends in the facetious worship of a donkey. The higher men thank Zarathustra for relieving them of their distress and teaching them to be content with life. The following morning, outside his cave, Zarathustra encounters a lion and a flock of doves, which he interprets as a sign that those whom he calls his children are near. As the higher men emerge from the cave, the lion roars at them, causing them to cry out and flee. Their cry reminds Zarathustra of the soothsayer's prediction that he would be tempted into feeling compassion for the higher man. He declares that this is over, and that from this time forward he will think of nothing but his work.Themes

Scholars have argued that "the worst possible way to understand Zarathustra is as a teacher of doctrines". Nonetheless ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' "has contributed most to the public perception of Nietzsche as philosophernamely, as the teacher of the 'doctrines' of the

Scholars have argued that "the worst possible way to understand Zarathustra is as a teacher of doctrines". Nonetheless ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' "has contributed most to the public perception of Nietzsche as philosophernamely, as the teacher of the 'doctrines' of the will to power

The will to power () is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's ...

, the overman and the eternal return".

Will to power

Nietzsche's thinking was significantly influenced by the thinking ofArthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

. Schopenhauer emphasised will, and particularly will to live

The will to live ( German: ''der Wille zum Leben'') is a concept developed by the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, representing an irrational "blind incessant ''impulse'' without knowledge" that drives instinctive behaviors, causing an end ...

. Nietzsche emphasised ''Wille zur Macht'', or will to power.

Nietzsche was not a systematic philosopher and left much of what he wrote open to interpretation. Receptive fascists are said to have misinterpreted the will to power, having overlooked Nietzsche's distinction between ''Kraft'' ‘force, strength’ and ''Macht'' ‘power, might’.

Scholars have often had recourse to Nietzsche's notebooks, where will to power is described in ways such as "willing-to-become-stronger 'Stärker-werden-wollen'' willing growth".

''Übermensch''

It is allegedly "well-known that as a term, Nietzsche’s Übermensch derives fromLucian of Samosata

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syria (region), Syrian satire, satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with whi ...

's hyperanthropos".Babich, Babette, "Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and Parodic Style: On Lucian’s Hyperanthropos and Nietzsche’s Übermensch" (2013). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 56.

https://research.library.fordham.edu/phil_babich/56 This hyperanthropos, or "overman," appears in Lucian's Menippean satire ''Κατάπλους ἢ Τύραννος'', usually translated ''Downward Journey or The Tyrant''. This hyperanthropos is "imagined to be superior to others of 'lesser' station in this-worldly life and the same tyrant after his (comically unwilling) transport into the underworld".

Nietzsche celebrated Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

as an actualisation of the Übermensch.

Eternal recurrence

Nietzsche includes some brief writings on eternal recurrence in his earlier book ''The Gay Science''. Zarathustra also appears in that book. In ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', the eternal recurrence is, according to Nietzsche, the "fundamental idea of the work". Interpretations of the eternal recurrence have mostly revolved around cosmological and attitudinal and normative principles. As a cosmological principle, it has been supposed to mean that time is circular, that all things recur eternally. A weak attempt at proof has been noted in Nietzsche's notebooks, and it is not clear to what extent, if at all, Nietzsche believed in the truth of it. Critics have mostly dealt with the cosmological principle as a puzzle of ''why'' Nietzsche might have touted the idea. As an attitudinal principle it has often been dealt with as a thought experiment, to see how one would react, or as a sort of ultimate expression of life-affirmation, as if one should ''desire'' eternal recurrence. As a normative principle, it has been thought of as a measure or standard, akin to a "moral rule".Criticism of religion

Nietzsche studied extensively and was very familiar with Schopenhauer and Christianity andBuddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

, each of which he considered nihilistic and "enemies to a healthy culture". ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' can be understood as a "polemic

Polemic ( , ) is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial to ...

" against these influences.

Though Nietzsche "probably learned Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

while at Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

from 1865 to 1868", and "was probably one of the best read and most solidly grounded in Buddhism for his time among Europeans", Nietzsche was writing when Eastern thought was only beginning to be acknowledged in the West, and Eastern thought was easily misconstrued. Nietzsche's interpretations of Buddhism were coloured by his study of Schopenhauer, and it is "clear that Nietzsche, as well as Schopenhauer, entertained inaccurate views of Buddhism". An egregious example has been the idea of ''śūnyatā

''Śūnyatā'' ( ; ; ), translated most often as "emptiness", " vacuity", and sometimes "voidness", or "nothingness" is an Indian philosophical concept. In Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, and other Indian philosophical traditions, the concept ...

'' as "nothingness" rather than "emptiness". "Perhaps the most serious misreading we find in Nietzsche's account of Buddhism was his inability to recognize that the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness was an initiatory stage leading to a reawakening". Nietzsche dismissed Schopenhauer and Christianity and Buddhism as pessimistic and nihilistic, but, according to Benjamin A. Elman, " en understood on its own terms, Buddhism cannot be dismissed as pessimistic or nihilistic". Moreover, answers which Nietzsche assembled to the questions he was asking, not only generally but also in ''Zarathustra'', put him "very close to some basic doctrines found in Buddhism". An example is when Zarathustra says that "the soul is only a word for something about the body".

Nihilism

One of the most vexed points in discussions of Nietzsche has been whether or not he was a nihilist. Though arguments have been made for either side, what is clear is that Nietzsche was at least ''interested'' innihilism

Nihilism () encompasses various views that reject certain aspects of existence. There have been different nihilist positions, including the views that Existential nihilism, life is meaningless, that Moral nihilism, moral values are baseless, and ...

.

As far as nihilism touched other people, at least, metaphysical understandings of the world were progressively undermined until people could contend that "God is dead". Without God, humanity was greatly devalued. Without metaphysical or supernatural lenses, humans could be seen as animals with primitive drives which were or could be sublimated. According to Hollingdale, this led to Nietzsche's ideas about the will to power. Likewise, "''Sublimated will to power'' was now the Ariadne

In Greek mythology, Ariadne (; ; ) was a Cretan princess, the daughter of King Minos of Crete. There are variations of Ariadne's myth, but she is known for helping Theseus escape from the Minotaur and being abandoned by him on the island of N ...

's thread tracing the way out of the labyrinth of nihilism".

Style

The nature of the text is musical and operatic. While working on it Nietzsche wrote "of his aim 'to become Wagner's heir'". Nietzsche thought of it as akin to a symphony or opera. "No lesser a symphonist thanGustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic music, Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and ...

corroborates: 'His ''Zarathustra'' was born completely from the spirit of music, and is even "symphonically constructed"'". Nietzsche The length of paragraphs and the punctuation and the repetitions all enhance the musicality.The title is ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra''. Much of the book is what Zarathustra said. What Zarathustra says Nietzsche would often appropriate masks and models to develop himself and his thoughts and ideas, and to find voices and names through which to communicate. While writing ''Zarathustra'', Nietzsche was particularly influenced by "the language of Luther and the poetic form of the Bible". But ''Zarathustra'' also frequently alludes to or appropriates from Hölderlin's '' Hyperion'' and

Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

's ''Faust'' and Emerson's ''Essays'', among other things. It is generally agreed that the sorcerer is based on Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

and the soothsayer is based on Schopenhauer.

The original text contains a great deal of word-play. For instance, words beginning with ''über

''Über'' (, sometimes written ''uber'' in English-language publications) is a German language word meaning "over", "above" or "across". It is an etymological twin with German ''ober'', and is a cognate (through Proto-Germanic) with English ...

'' ('over, above') and ('down, below') are often paired to emphasise the contrast, which is not always possible to bring out in translation, except by coinages. An example is ''untergang'' ( lit. 'down-going'), which is used in German to mean 'setting' (as in, of the sun), but also 'sinking', 'demise', 'downfall', or 'doom'. Nietzsche pairs this word with its opposite ''übergang'' ('over-going'), used to mean 'transition'. Another example is '' übermensch'' ('overman' or 'superman').

Reception

Nietzsche considered ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' his ''magnum opus

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

'', writing:

In a letter of February 1884, he wrote:

To this, Parkes has said: "Many scholars believe that Nietzsche managed to make that step". But critical opinion varies extremely. The book is "a masterpiece of literature as well as philosophy" and "in large part a failure".

The style of the book, along with its ambiguity

Ambiguity is the type of meaning (linguistics), meaning in which a phrase, statement, or resolution is not explicitly defined, making for several interpretations; others describe it as a concept or statement that has no real reference. A com ...

and paradox

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true or apparently true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictor ...

ical nature, has helped its eventual enthusiastic reception by the reading public but has frustrated academic attempts at analysis (as Nietzsche may have intended). ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' remained unpopular as a topic for scholars (especially those in the Anglo-American analytic tradition) until the latter half of the 20th century brought widespread interest in Nietzsche and his unconventional style.

The critic Harold Bloom

Harold Bloom (July 11, 1930 – October 14, 2019) was an American literary critic and the Sterling Professor of humanities at Yale University. In 2017, Bloom was called "probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world". Af ...

criticized ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'' in ''The Western Canon

''The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages'' is a 1994 book about Western literature by the American literary critic Harold Bloom, in which the author defends the concept of the Western canon by discussing 26 writers whom he sees as c ...

'' (1994), calling it "a gorgeous disaster" and "unreadable". Other commentators have suggested that Nietzsche's style is intentionally ironic

Irony, in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what, on the surface, appears to be the case with what is actually or expected to be the case. Originally a rhetorical device and literary technique, in modernity, modern times irony has a ...

for much of the book.

English translations

The first English translation of ''Zarathustra'' was published in 1896 by Alexander Tille.Common (1909)

Thomas Common published a translation in 1909 which was based on Alexander Tille's earlier attempt.Nietzsche, Friedrich. Trans. Kaufmann, Walter. ''The Portable Nietzsche''. 1976, pp. 108–09. Kaufmann's introduction to his own translation included a blistering critique of Common's version; he notes that in one instance, Common has taken the German "most evil" and rendered it "baddest", a particularly unfortunate error not merely for his having coined the term "baddest", but also because Nietzsche dedicated a third of '' The Genealogy of Morals'' to the difference between "bad" and "evil". This and other errors led Kaufmann to wonder whether Common "had little German and less English". The German text available to Common was considerably flawed.Nietzsche, Friedrich. Trans. Martin, Clancy. ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra''. 2005, p. xxxiii. From ''Zarathustra's Prologue'':Kaufmann (1954) and Hollingdale (1961)

The Common translation remained widely accepted until more critical translations, titled ''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', were published by Walter Kaufmann in 1954, and R.J. Hollingdale in 1961. Clancy Martin states the German text from which Hollingdale and Kaufmann worked was untrue to Nietzsche's own work in some ways. Martin criticizes Kaufmann for changing punctuation, altering literal and philosophical meanings, and dampening some of Nietzsche's more controversial metaphors. Kaufmann's version, which has become the most widely available, features a translator's note suggesting that Nietzsche's text would have benefited from an editor; Martin suggests that Kaufmann "took it upon himself to become ietzsche'seditor". Kaufmann, from ''Zarathustra's Prologue'': Hollingdale, from ''Zarathustra's Prologue'':21st-century translations

Parkes (2005)

Graham Parkes describes his own 2005 translation as trying to convey the musicality of the text.Parkes, Graham. 2005.Introduction

. In ''Thus spoke Zarathustra''.

Del Caro (2006)

In 2006, Cambridge University Press published a translation by Adrian Del Caro (edited by Del Caro and Robert Pippin); this edition aims to restore the original versification of Nietzsche's text and "capture its poetic brilliance", in the words of the publisher.Further reading

Selected editions

English

*''Thus Spake Zarathustra'', translated by Alexander Tille. New York: Macmillan. 1896. *''Thus Spake Zarathustra'', trans. Thomas Common. Edinburgh: T. N. Foulis. 1909. *''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York:Random House

Random House is an imprint and publishing group of Penguin Random House. Founded in 1927 by businessmen Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer as an imprint of Modern Library, it quickly overtook Modern Library as the parent imprint. Over the foll ...

. 1954.

** Reprints: In ''The Portable Nietzsche'', New York: Viking Press. 1954; Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

Penguin Books Limited is a Germany, German-owned English publishing, publishing house. It was co-founded in 1935 by Allen Lane with his brothers Richard and John, as a line of the publishers the Bodley Head, only becoming a separate company the ...

. 1976

*''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', trans. R. J. Hollingdale. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 1961.

*''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', trans. Graham Parkes. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics. 2005.

*''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', trans. Clancy Martin. Barnes & Noble Books. 2005.

*''Thus Spoke Zarathustra'', trans. Adrian del Caro and edited by Robert Pippin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

. 2006.

*''Thus Spake Zarathustra'', trans. Michael Hulse

Michael Hulse (born 1955) is an English poet, translator and critic, notable especially for his translations of German novels by W. G. Sebald, Herta Müller, and Elfriede Jelinek.

Life and works

Hulse was educated locally in Stoke-on-Trent unti ...

. New York Review Books. 2022.

German

*''Also sprach Zarathustra'', edited by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag (study edition of the standard German Nietzsche edition). * ''Also sprach Zarathustra'' (bilingual ed.) (in German and Russian), with 20oil painting

Oil painting is a painting method involving the procedure of painting with pigments combined with a drying oil as the Binder (material), binder. It has been the most common technique for artistic painting on canvas, wood panel, or oil on coppe ...

s by Lena Hades. Moscow: Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences

The Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences ( Russian: Институт философии РАН) is the central research institution of Russia which conducts scientific work in the main areas and topical issues of modern philos ...

. 2004. .

Commentaries and introductions

English

* ''Nietzsche's 'Thus Spoke Zarathustra': Before Sunrise'' (essay collection), edited by James Luchte. London:Bloomsbury Publishing

Bloomsbury Publishing plc is a British worldwide publishing house of fiction and non-fiction. Bloomsbury's head office is located on Bedford Square in Bloomsbury, an area of the London Borough of Camden. It has a US publishing office located in ...

. 2008. .

* Higgins, Kathleen. 987 2010. ''Nietzsche's Zarathustra'' (rev. ed.). Philadelphia: Temple University Press

Temple University Press is a university press founded in 1969 that is part of Temple University (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). It is one of thirteen publishers to participate in the Knowledge Unlatched pilot, a global library consortium approach ...

.

* OSHO. 1987. "Zarathustra: A God That Can Dance". Pune, India: OSHO Commune International.

*OSHO. 1987. "Zarathustra: The Laughing Prophet". Pune, India: OSHO Commune International.

* Lampert, Laurence. 1989. ''Nietzsche's Teaching: An Interpretation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra''. New Haven: Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day and Clarence Day, grandsons of Benjamin Day, and became a department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and ope ...

.

* Rosen, Stanley. 1995. ''The Mask of Enlightenment: Nietzsche's Zarathustra''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

.

** 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2004.

* Seung, T. K. 2005. ''Nietzsche's Epic of the Soul: Thus Spoke Zarathustra''. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.German

* Naumann, Gustav. 1899–1901.Zarathustra-Commentar

' (in German), 4 vols. Leipzig: Haessel. * Zittel, Claus. 2011. ''Das ästhetische Kalkül von Friedrich Nietzsches 'Also sprach Zarathustra. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. . * Schmidt, Rüdiger. "Introduction" (in German). In ''Nietzsche für Anfänger: Also sprach Zarathustra – Eine Lese-Einführung''. * Zittel, Claus: Wer also erzählt Nietzsches Zarathustra?, in: Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 95, (2021), 327–351.

See also

* Also sprach Zarathustra (Richard Strauss' tone poem, inspired by Nietzsche's work) * Faith in the Earth *''Gathas'' (Hymns of Zoroaster) * Influence and reception of Friedrich Nietzsche * Buddhism and Western philosophy#Nietzsche, Nietzsche and Buddhism * Manusmriti#Friedrich Nietzsche, Nietzsche on the ''Manusmriti'' (Ancient text, otherwise known as ''Mānava-Dharmaśāstra'' or ''Laws of Manu''). * Philosophy of Friedrich NietzscheReferences

Notes

Citations

External links

*''Also sprach Zarathustra''

at Nietzsche Source

Project Gutenberg's etext of ''Also sprach Zarathustra'' (the German original)

Project Gutenberg's etext of ''Thus Spake Zarathustra'', translated by Thomas Common

* {{Authority control Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1883 German novels,