Thomas Stukley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Stucley (4 August 1578)Vivian 1895, p. 721, pedigree of Stucley was an English mercenary who fought in France, Ireland and at the

Thomas Stucley (4 August 1578)Vivian 1895, p. 721, pedigree of Stucley was an English mercenary who fought in France, Ireland and at the

Thomas Stucley (4 August 1578)Vivian 1895, p. 721, pedigree of Stucley was an English mercenary who fought in France, Ireland and at the

Thomas Stucley (4 August 1578)Vivian 1895, p. 721, pedigree of Stucley was an English mercenary who fought in France, Ireland and at the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval warfare, naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League (1571), Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of t ...

before being killed at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir

The Battle of Alcácer Quibir (also known as "Battle of Three Kings" () or "Battle of Wadi al-Makhazin" () in Morocco) was fought in northern Morocco, near the town of Ksar-el-Kebir (variant spellings: ''Ksar El Kebir'', ''Alcácer-Quivir'', ...

in 1578. He was a Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

recusant

Recusancy (from ) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign of Elizabeth I, and temporarily repea ...

and a rebel against the Protestant Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

.

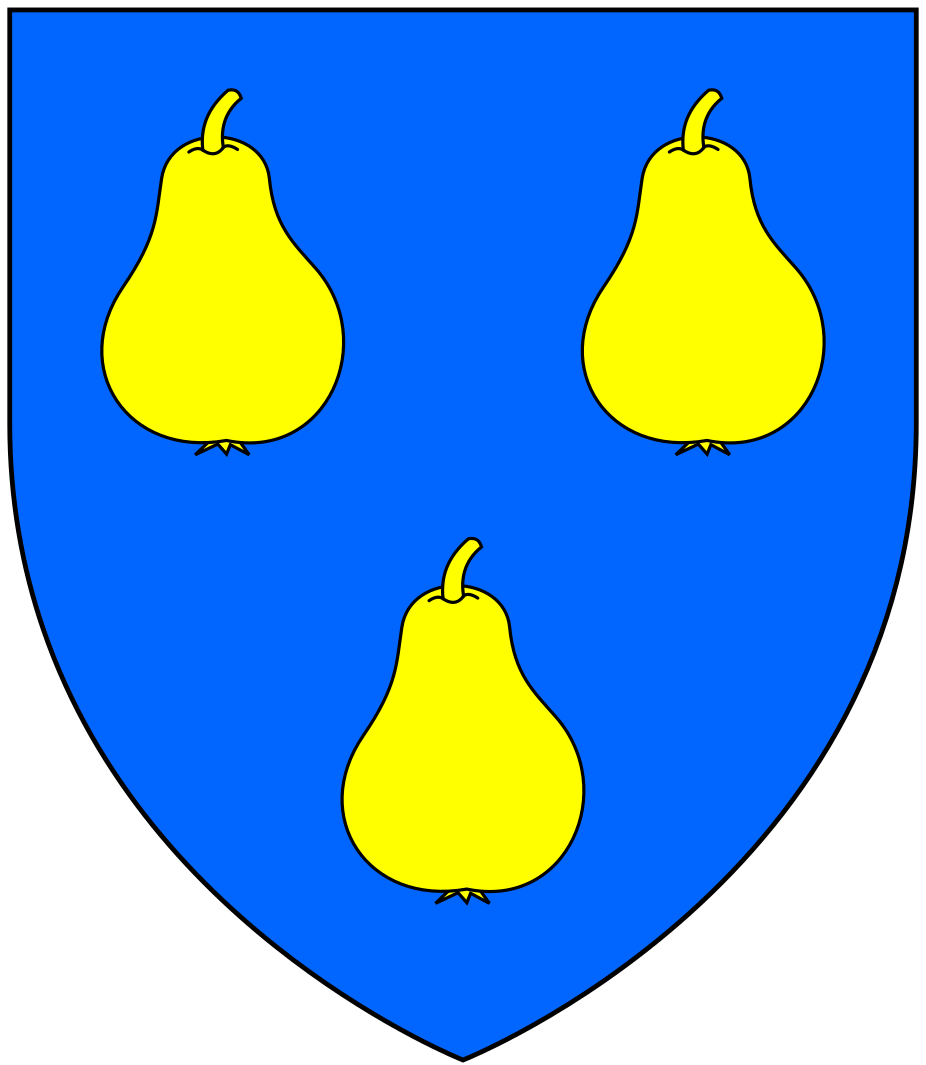

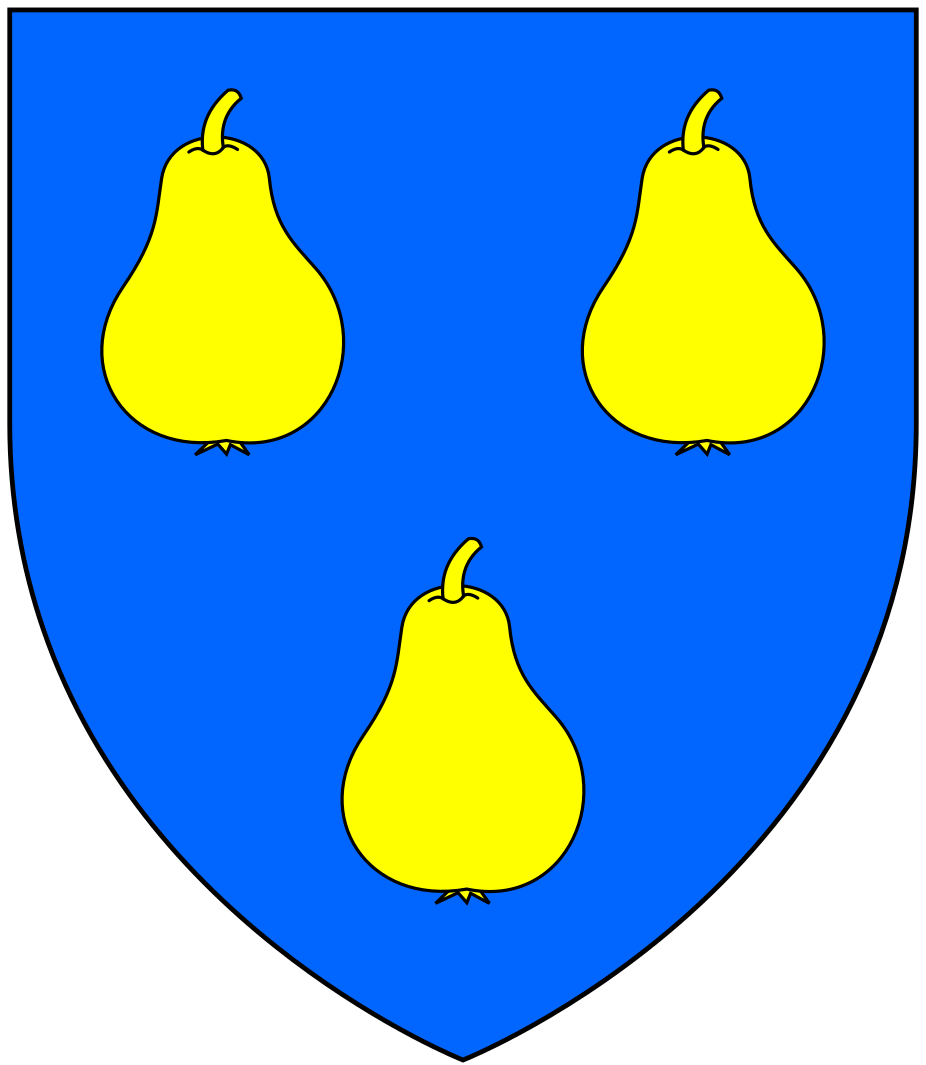

Family

He was a younger son of Sir Hugh Stucley (1496–1559)lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of the manor of Affeton, in the parish of West Worlington in Devon, head of an ancient gentry family, a Knight of the Body to King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

and Sheriff of Devon

The High Sheriff of Devon is the Kings's representative for the County of Devon, a territory known as his/her bailiwick. Selected from three nominated people, they hold the office for one year. They have judicial, ceremonial and administrative f ...

in 1545. His mother was Jane Pollard, daughter of Sir Lewis Pollard (1465–1526), lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of the manor of King's Nympton

The Manor of King's Nympton was a Manorialism, manor largely co-terminous with the parish of King's Nympton in Devon, England.

Descent of the manor

At the time of the Domesday Book of 1086, the whole manor of ''Nimetone'', in the Hundred (county ...

, Devon, Justice of the Common Pleas

Justice of the Common Pleas was a puisne judicial position within the Court of Common Pleas (England), Court of Common Pleas of England and Wales, under the Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Chief Justice. The Common Pleas was the primary court o ...

, and his wife Anne Hext.

It has been alleged that he was instead an illegitimate son of King Henry VIII. Details of any wives or children he may have had are imprecise.

Career

Stucley's early mentors wereCharles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk

Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk ( – 22 August 1545) was an English military leader and courtier. Through his third wife, Mary Tudor, he was the brother-in-law of King Henry VIII.

Biography

Born in 1484, Charles Brandon was the secon ...

, and then the Bishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. The current bishop is Mike Harrison (bishop), Mike Harrison, since 2024.

From the first bishop until the sixteent ...

, in whose household he held a post. He was present at Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

during the siege of 1544–45, and again in 1550 on the surrender of the city to the English. From 1547 to 1550, he was a standard-bearer at Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

, and then entered the service of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp (150022 January 1552) was an English nobleman and politician who served as Lord Protector of England from 1547 to 1549 during the minority of his nephew King E ...

. After his master's arrest in 1551 a warrant was issued against him, but he succeeded in escaping to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, where he served in the French army.

His military talents brought him to the attention of Henri III de Montmorency, and he was sent to England with a letter of recommendation from Henry II of France

Henry II (; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was List of French monarchs#House of Valois-Angoulême (1515–1589), King of France from 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I of France, Francis I and Claude of France, Claude, Du ...

to his supposed half-brother Edward VI of England

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

. On his arrival he proceeded on 16 September 1552 to reveal the French plans for the capture of Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

and for a descent upon England, the furtherance of which had, according to his account, been the object of his mission to England. John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jane ...

evaded the payment of any reward to Stucley, and sought to gain the friendship of the French king by pretending to disbelieve Stucley's statements.

Stucley, who may well have been the originator of the plans adopted by the French, was imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

for some months. Having run through his brother's inheritance, he was prosecuted for debt on his release in August 1553 and was compelled to become a soldier of fortune once more. This was not his only financial difficulty: once, claiming a legacy, he broke into the late testator's house and searched the coffers, in defiance of a court injunction. In another episode, he was imprisoned in the Tower at the suit of an Irishman he had robbed.

He returned to England in December 1554 in the train of Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy

Emmanuel Philibert (; ; 8 July 1528 – 30 August 1580), known as (; "Ironhead", because of his military career), was Duke of Savoy and ruler of the Savoyard states from 17 August 1553 until his death in 1580. He is notably remembered for resto ...

, after obtaining an amnesty against his creditors' suits, possibly thanks to the Duke of Suffolk. His credit temporarily improved upon his marriage to Anne Curtis, granddaughter and heir of Sir Thomas Curtis, but he was reputed to squander £100 a day and to have sold the blocks of tin with which his father-in-law had paved the yard of his London house. Within a few months, a warrant for his arrest was issued on a charge of uttering false money and he fled abroad again, deserting his wife, to enter the service of the duke of Savoy. He then fought on the victorious side at the Battle of St. Quentin in 1557.

In 1558, Stucley was summoned before the council on a charge of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

, although he was again acquitted owing to insufficient evidence, and managed to retain the favour of Queen Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous ...

. On the death of his wife's grandfather at the beginning of Elizabeth's reign he came into money, and he accommodated himself to the Protestant succession and became a supporter of Sir Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was ove ...

. In 1561, he was given a captaincy at Berwick, where he lived sumptuously; during the winter, he made firm friends with the Gaelic nobleman Shane O'Neill of Ulster, upon the latter's visit to court at London. In 1562, he obtained a warrant permitting him to bring French ships into English ports although England and France were only nominally at peace.

At about this time, on being presented to the queen he said he would prefer to be sovereign of a molehill than the subject of the greatest king in Christendom and that he had a presentiment he would be a prince before he died. She is said to have remarked,

"I hope I shall hear from you when you are installed in your principality". He responded that she surely would, and she demanded,

"''In what language?''" He answered: "''In the style of princes, to our dearest sister.''"

Stucley then devised a plan for a colony in Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, at the time hotly contested by rival Spanish and French settlers (see Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

). To this end, he persuaded the queen to supply a ship of 100 tons (including 100 men, plus sailors), to supplement his fleet of five vessels. Having staged a naval pageant for the queen on the Thames, he promptly sailed his fleet to the coast of Munster in Ireland in June 1563 to go privateering against French, Spanish and Portuguese ships. After repeated remonstrances on the part of the offended powers, Elizabeth disavowed Stucley and sent a naval force under the command of Sir Peter Carew to arrest him. One of his ships was taken in Cork haven, and Stucley surrendered, but he was acquitted once again, with O'Neill pleading his case through diplomatic channels.

Ireland

The meeting with O'Neill led to an extended interest in Irish affairs on Stucley's part. He was recommended by the queen to theLord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ov ...

of Ireland, Sir Thomas Radclyffe, Earl of Sussex

Earl of Sussex is a title that has been created several times in the Peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. The early Earls of Arundel (up to 1243) were often also called Earls of Sussex.

The fifth creation came in the Pee ...

, on 30 June 1563, and in 1566 was employed as a captain by the Lord Deputy

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive (government), executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland ...

, Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586) was an English soldier, politician and Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Background

He was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst (1482 – 11 February 1553) and Anne Pakenham (1511 – 22 Oc ...

, in a vain effort to induce O'Neill to enter into negotiations with the government. The Ulster lord sought to use him as intermediary with Sidney and in the same year requested his presence in fighting the Scots, an arrangement favoured by the lord deputy. Sidney then sought permission of the crown for Stucley to purchase the estates and office of Sir Nicholas Bagenal, marshal of Ireland, for £3,000, but Elizabeth refused to permit the transaction. The lands lay mostly in the east of Ulster, a territory anciently in Hiberno-Norman

Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans (; ) is a modern term for the descendants of Norman settlers who arrived during the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. Most came from England and Wales. They are distinguished from the native ...

possession, which was much fought over by the Irish and Scots, and would be used by the English within a decade as a base for their efforts at colonisation of the province (see Plantations of Ireland#Early plantations (1556–1576)).

Undeterred by this failure, Stucley was appointed seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

of Kavanagh's country in south-east Leinster, and had some say in the controversial land claims of his adversary, Peter Carew (who succeeded him in that office). He went on to buy lands from Sir Nicholas Heron in the adjacent County Wexford

County Wexford () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster and is part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. Named after the town of Wexford, it was ba ...

, and was appointed by Sidney to the office of seneschal there, but the queen objected to the appointment and in June 1568 he was dismissed in favour of Sir Nicholas White. Stucley had fallen prey to the disputes between Sidney and White's patron, the Earl of Ormonde, which resulted, in the following year, in Elizabeth rebuking Sidney for his use of Stucley in the negotiations with O'Neill. In June 1569 Stucley was committed to custody in Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

for 18 weeks, on White's claim that he had used 'coarse language' against the queen and supported 'certain rebels'.

Spain

Again, Stucley was acquitted, and the authorities released him in October 1569. He had been suspected of proposing an invasion of Ireland to KingPhilip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

, and soon after his release he offered his services to Fénelon, the French ambassador in London. He returned to Ireland in 1570, where he fitted out a ship at Waterford

Waterford ( ) is a City status in Ireland, city in County Waterford in the South-East Region, Ireland, south-east of Ireland. It is located within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster. The city is situated at the head of Waterford H ...

and made a great show of his piety, proceeding through the streets of the city on his knees as he offered himself up to God. He then sailed from Waterford on 17 April, supposedly for London, but his real destination was Vimeiro

Vimeiro () is a freguesia (civil parish) in the municipality of Lourinhã in west-central Portugal. It is in the Lisboa (district), District of Lisboa. The population in 2011 was 1,470,Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

. He had 28 men on board, but only the sole Italian knew their course, and the rest fell into despair when they arrived in Portugal after a five-day voyage.

Philip II invited him to Madrid, where he was loaded with honours, probably with a view to impressing upon Elizabeth the threat of an invasion of Ireland to detract from English support for the Dutch rebels in the Netherlands. With the approbation of the Duke of Feria, Stucley was known at the Spanish court as the "Duke of Ireland

Duke of Ireland is a title that was created in 1386 for Robert de Vere, 9th Earl of Oxford (1362–1392), the favourite of King Richard II of England, who had previously been created Marquess of Dublin. Both were peerages for one life only. At ...

", and was established with an allowance in a villa near Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

.

Speculation about Stucley's future role became intense. In 1570, it was claimed that he had sought to interfere in the Ridolfi Plot

The Ridolfi plot was a Catholic plot in 1571 to overthrow Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. The plot was hatched and planned by Roberto Ridolfi, an international banker who was able to travel between Bruss ...

with an attack on Ireland in the following year during the planned invasion of England from Flanders. The Irish invasion was to have been aided by the Plymouth fleet of Sir John Hawkins, who betrayed the supposed plot to the privy council, leading to the arrest of the Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, (10 March 1536 or 1538 2 June 1572), was an English nobleman and politician. He was a second cousin of Queen Elizabeth I and held many high offices during the earlier part of her reign.

Norfolk was the s ...

.

On 12 February 1571, the king was informed by the Spanish ambassador that news was had in London from France that the pope had ceded to the Spanish crown the kingdom created for Philip and Queen Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous ...

, which had fallen vacant upon the excommunication of Elizabeth by Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V, OP (; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (and from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 January 1566 to his death, in May 1572. He was an ...

, in his 1570 papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

''Regnans in Excelsis

''Regnans in Excelsis'' ("Reigning on High") is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime," declared h ...

'', and that it was rumoured that Stucley was to be sent to England with 14 to 15 companies of troops.

Amidst this international feinting and shaping, the Catholic Archbishop of Cashel

The Archbishop of Cashel () was an archiepiscopal title which took its name after the town of Cashel, County Tipperary in Ireland. Following the Reformation, there had been parallel apostolic successions to the title: one in the Catholic Church ...

, Maurice Reagh Fitzgibbon – an ally of the Irish leader in Munster James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald – made some effort while in Spain to discredit Stucley's ambitions , much to the displeasure of Feria, and was supported by the Duke of Alba

Duke of Alba de Tormes (), commonly known as Duke of Alba, is a title of Spanish nobility that is accompanied by the dignity of Grandee of Spain. In 1472, the title of ''Count of Alba de Tormes'', inherited by García Álvarez de Toledo, wa ...

, who dismissed the proposed invasion on the ground that once England fell, Ireland would fall of itself.

The archbishop's brief was to request the appointment of John of Austria

John of Austria (, ; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the illegitimate son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Charles V recognized him in a codicil to his will. John became a military leader in the service of his half-brother, King Phi ...

, nicknamed Don John, as king of Ireland. On removing to Paris, Fitzgibbon informed the English ambassador there, Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her " spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wa ...

, of Stucley's plan. In 1570, Stucley sought to have an English spy, Oliver King, brought before the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition () was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile and lasted until 1834. It began toward the end of ...

. King had a history of attendance at Mass and of knocking his breast daily and so was merely stripped and banished, but then had to cross the Pyrenees in the snow while Stucley's men pursued him. Stucley obtained his passport to leave Spain after Elizabeth demanded his dismissal.

Stucley moved to Rome, where he found favour with Pope Pius V, who had excommunicated Elizabeth in 1571. He was given the command of three galleys at the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval warfare, naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League (1571), Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of t ...

(7 October 1571), and showed great valour. It was a crucial victory for the Holy League over the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

of Selim II

Selim II (; ; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond () or Selim the Drunkard (), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1566 until his death in 1574. He was a son of Suleiman the Magnificent and his wife Hurrem Sul ...

, and allowed Spain to devote more resources to its campaigns in northern Europe.

Stucley's exploits restored him to favour in Madrid, and by the end of March 1572 he was at Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, offering to hold the narrow seas against the English with a fleet of twenty ships. In four years (1570–1574) he is said to have received over 27,000 ducats from Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

, but wearied by the king's delays he sought more serious assistance from the new pope, Gregory XIII

Pope Gregory XIII (, , born Ugo Boncompagni; 7 January 1502 – 10 April 1585) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 May 1572 to his death in April 1585. He is best known for commissioning and being the namesake ...

, who aspired to make his son Giacomo Boncompagni

Giacomo Boncompagni (also ''Jacopo Boncompagni''; 8 May 1548 – 18 August 1612) was an Italian feudal lord of the 16th century, the illegitimate son of Pope Gregory XIII (Ugo Boncompagni). He was also Duke of Sora, Aquino, Arce and Arpino, a ...

King of Ireland

Monarchical systems of government have existed in Ireland from ancient times. This continued in all of Ireland until 1949, when the Republic of Ireland Act removed most of Ireland's residual ties to the British monarch. Northern Ireland, as p ...

.

Rome

Stucley allied with Fitzmaurice and moved to Rome in 1575, where he is said to have walked about the streets and churches barefoot and bare-legged. In June, Stucley had an interview at Naples with his Lepanto commander Don John, and passed on details of the plans for an October expedition. The intention was to deliverMary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, from prison and take possession of England. Don John, who was now in charge of the Spanish forces in Flanders, said the king would have to approve, and that 3,000 men were too few, but was cautiously optimistic that the expedition would help to contain the rebellion in the Netherlands.

In 1575, Friar Patrick O'Healy arrived at Rome bearing a letter from the king and announcing that he sought sanction for an unnamed Irish gentleman to revolt and to request assistance; he insisted Philip II had given his blessing. Pope Gregory stressed that the crown ought not to go to a French or Spanish claimant, but to a native Catholic, that is, Mary, Queen of Scots, lest the king gain too much power and territory; he was opposed to Don John being crowned in Ireland. The king disputed O'Healy's authority to enter discussion on the Irish matter and queried the Pope's opposition to the increase of Spanish authority.

The Pope was willing to guarantee six months' pay for 200 men and their shipping expenses to go to England in his name, and wondered if a personal attempt might be made against Elizabeth. Later, it was suggested that 5,000 go to Liverpool and free Mary before possessing the country, or go to Ireland. Pope Gregory bargained for Philip II to defray the entire expense of the expedition, and suggested that if the Vatican were to pitch in then it should receive some benefit in Italy by way of material return. The Spanish thought the leader of the expedition should be married, so as to prevent papal approval of a match with Mary.

British spies had been sending home rumours of Stucley's plans since Archbishop Fitzgibbon's intervention in Spain. In 1572, Oliver King informed London of invasion plans; in March 1573 Elizabeth's spymaster Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley, received intelligence that certain "''decayed gentlemen''" were to join Stucley in Spain for the invasion of Ireland. At their first encounter, Walsingham had not known what to make of Fitzgibbon, realising that an agent of Burghley's had sown dissension between the archbishop and Stucley, but in 1575 he did have intelligence of Stucley's alliance with Fitzmaurice, at a time when the nuncio at Madrid was urging an invasion of England. In 1578 Walsingham had similar intelligence, and having failed to induce Archbishop Fitzgibbon to give up his secrets in return for his passage back to Ireland, procured his arrest in Scotland.

Invasion expedition

On 1 October 1578, Don John died while on campaign in southern Belgium, of camp fever (typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

). His death disrupted plans for the invasion of England, but there was still stomach for supporting the Irish. In 1576 Fitzmaurice had been warmly received at Rome, where William Allen, later a cardinal, was also present, having presented to the Pope a plot for the invasion of England through Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, with 5,000 musketeers under Stucley's command.

Now, in 1578, the Pope provided Stucley with infantry and he set out with 2,000 fighting men. The force had, it was claimed, been raised by enlisting Apennine highwaymen and robbers in return for pardons and 50-day indulgences, the latter to be gained by contemplation of crucifixes supplied to Stucley. They were commanded by professional officers under Hercules of Pisano, and also Giuseppi who went on to command the Smerwick garrison at the beginning of the Second Desmond Rebellion

The Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–1583) was the more widespread and bloody of the two Desmond Rebellions in Ireland launched by the FitzGerald Dynasty of County Desmond, Desmond in Munster against English rule. The second rebellion began in ...

. In sum, Stucley's ranks rose to 4,000.

Stucley sailed for Ireland from Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia (, meaning "ancient town") is a city and major Port, sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea west-northwest of Rome. Its legal status is a ''comune'' (municipality) of Metropolitan City of Rome Capital, Rome, Lazio.

The harbour is formed by ...

in March 1578. In April, he reached Cadiz with rotted ships, where he issued magnificent passports to Irishmen returning home, describing himself as Marquess of Leinster

Leinster ( ; or ) is one of the four provinces of Ireland, in the southeast of Ireland.

The modern province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige, which existed during Gaelic Ireland. Following the 12th-century ...

(a title bestowed by the Pope). Philip II sent him on to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, where he was to meet Fitzmaurice and secure better ships before sailing for Ireland.

Here, King Sebastian of Portugal invited Stucley to take up a command in his army, which included Portuguese and German mercenaries, in preparation for an invasion of Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

(an ally of England against Spain) in an attack upon the Moors. Stucley abandoned the Irish invasion, and destroyed the hopes of help in Munster. Stucley is said to have declared that he knew Ireland as well as the best and that there were only to be got there "''hunger and lice''".

The Jesuit polemicist Nichola Sanders and Irish members of the expedition made their way back to Rome, and continued the now ill-fated invasion, deprived of most of its money and men by Stucley's desertion.

On landing in Morocco, Stucley objected to marching straight away against a vast force of Moors and scorned the Portuguese king's troops and tactics. He reportedly fought with courage on 4 August 1578 at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir, commanding the centre, but was killed early in the day when a cannonball cut off his legs—or perhaps, as tradition asserted, he was murdered by his Italian soldiers after the Portuguese had been defeated. The historian Jerry Brotton writes of him, "He might not have 'given a fart' about Elizabeth, but it may have been one of her cannonballs that killed him".

Legacy

Stucley's career made a considerable impression on his contemporaries, and in death he attracted as much speculation and gossip as he had in life. A play generally assigned toGeorge Peele

George Peele (baptised 25 July 1556 – buried 9 November 1596) was an English translator, poet, and dramatist, who is most noted for his supposed, but not universally accepted, collaboration with William Shakespeare on the play ''Titus Andronic ...

, ''The Battell of Alcazar with the Death of Captain Stukely'', printed in 1594, was probably acted in 1592. It deals with Stucley's arrival in Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

and his Moorish expedition; in a long speech before his death he recapitulates the events of his life.

A later piece, '' The Famous History of the Life and Death of Captain Thomas Stukeley'', printed for Thomas Pavier

Thomas Pavier (died 1625) was a London publisher and bookseller of the early seventeenth century. His complex involvement in the publication of early editions of some of Shakespeare's plays, as well as plays of the Shakespeare Apocrypha, has l ...

(1605), which is possibly the Stewtle, played, according to Henslowe, on 11 December 1596, is a biographical piece dealing with successive episodes, and seems to be a patchwork of older plays on Dom António and on Stucley. His adventures also form the subject of various ballads.

There is a detailed biography of Stucley, based chiefly on the English, Venetian and Spanish state papers, in R Simpson's edition of the 1605 play (''School of Shakespeare'', 1878, vol. i.), where the Stucley ballads are also printed. References in contemporary poetry are quoted by Dyce

Dyce () is a suburb of Aberdeen, Scotland, situated on the River Don about northwest of the city centre. It is best known as the location of Aberdeen Airport.

History

Dyce is the site of an early medieval church dedicated to the 8th centu ...

in his introduction to ''The Battle of Alcazar'' in Peele's ''Works''.

References

Sources

* * T. Wright ''The History of Ireland'' v.II pp. 461 et seq. * Richard Bagwell, ''Ireland under the Tudors'' 3 vols. (London, 1885–1890) * John O'Donovan (ed.) ''Annals of Ireland by the Four Masters'' (1851). * ''Calendar of State Papers: Carew MSS'' 6 vols (London, 1867–1873). * ''Calendar of State Papers: Ireland'' (London) * Nicholas Canny ''The Elizabethan Conquest of Ireland'' (Dublin, 1976); ''Kingdom and Colony'' (2002) * Steven G. Ellis ''Tudor Ireland'' (London, 1985) * Cyril Falls ''Elizabeth's Irish Wars'' (1950; reprint London, 1996) * * * Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) ''The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620'', Exeter, 1895.Further reading

*''Sir Thomas Stucley, c. 1525-1578: Traitor extraordinary'' by John Izon (1956) *''The Mistresses of Henry VIII'' by Kelly Hart (2009) *''The Stukeley Plays: 'The Battle of Alcazar' by George Peele and 'The Famous History of the Life and Death of Captain Thomas Stukeley' '' by Charles Edelman * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stukley, Thomas 1520s births 1578 deaths Expatriates from the Kingdom of England English military personnel killed in action Recusants English mercenaries People from Mid Devon District People of Elizabethan Ireland 16th-century English soldiers 16th-century Roman Catholics Illegitimate children of Henry VIII of EnglandThomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

Deaths by cannonball