Thomas Huxley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English

Finally, Huxley was made Assistant Surgeon ('surgeon's mate', but in practice marine naturalist) to HMS ''Rattlesnake'', about to set sail on a voyage of discovery and surveying to New Guinea and Australia. The ''Rattlesnake'' left England on 3 December 1846 and, once it arrived in the southern hemisphere, Huxley devoted his time to the study of marine invertebrates. He began to send details of his discoveries back to England, where publication was arranged by Edward Forbes FRS (who had also been a pupil of Knox). Both before and after the voyage Forbes was something of a mentor to Huxley.

Huxley's paper "On the anatomy and the affinities of the family of Medusae" was published in 1849 by the

Finally, Huxley was made Assistant Surgeon ('surgeon's mate', but in practice marine naturalist) to HMS ''Rattlesnake'', about to set sail on a voyage of discovery and surveying to New Guinea and Australia. The ''Rattlesnake'' left England on 3 December 1846 and, once it arrived in the southern hemisphere, Huxley devoted his time to the study of marine invertebrates. He began to send details of his discoveries back to England, where publication was arranged by Edward Forbes FRS (who had also been a pupil of Knox). Both before and after the voyage Forbes was something of a mentor to Huxley.

Huxley's paper "On the anatomy and the affinities of the family of Medusae" was published in 1849 by the  The value of Huxley's work was recognised and, on returning to England in 1850, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the following year, at the age of twenty-six, he not only received the Royal Society Medal but was also elected to the Council. He met

The value of Huxley's work was recognised and, on returning to England in 1850, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the following year, at the age of twenty-six, he not only received the Royal Society Medal but was also elected to the Council. He met

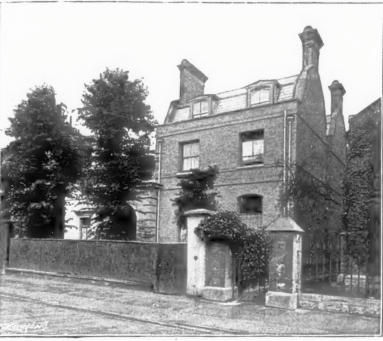

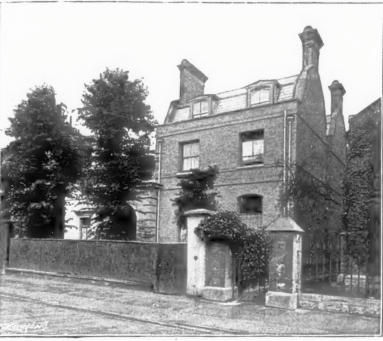

Huxley's London home, in which he wrote many of his works, was at 4 Marlborough Place,

Huxley's London home, in which he wrote many of his works, was at 4 Marlborough Place,  He died of a heart attack (after contracting influenza and pneumonia) in 1895 in Eastbourne, and was buried in London at East Finchley Cemetery. No invitations were sent out but two hundred people turned up for the funeral; they included

He died of a heart attack (after contracting influenza and pneumonia) in 1895 in Eastbourne, and was buried in London at East Finchley Cemetery. No invitations were sent out but two hundred people turned up for the funeral; they included

Huxley was originally not persuaded by "development theory", as evolution was once called. This can be seen in his savage review of Robert Chambers' ''

Huxley was originally not persuaded by "development theory", as evolution was once called. This can be seen in his savage review of Robert Chambers' ''

There were also some quite significant X-Club satellites such as William Flower and

There were also some quite significant X-Club satellites such as William Flower and

Huxley's interest in education went still further than school and university classrooms; he made a great effort to reach interested adults of all kinds: after all, he himself was largely self-educated. There were his lecture courses for working men, many of which were published afterwards, and there was the use he made of journalism, partly to earn money but mostly to reach out to the literate public. For most of his adult life, he wrote for periodicals—the ''

Huxley's interest in education went still further than school and university classrooms; he made a great effort to reach interested adults of all kinds: after all, he himself was largely self-educated. There were his lecture courses for working men, many of which were published afterwards, and there was the use he made of journalism, partly to earn money but mostly to reach out to the literate public. For most of his adult life, he wrote for periodicals—the ''

''The scientific aspects of positivism''

Huxley 1870 ''Lay Sermons, Addresses and Reviews'' p. 149). Huxley's dismissal of positivism damaged it so severely that Comte's ideas withered in Britain.

During his life, and especially in the last ten years after retirement, Huxley wrote on many issues relating to the humanities.

Perhaps the best known of these topics is ''Evolution and Ethics'', which deals with the question of whether biology has anything particular to say about moral philosophy. Both Huxley and his grandson

During his life, and especially in the last ten years after retirement, Huxley wrote on many issues relating to the humanities.

Perhaps the best known of these topics is ''Evolution and Ethics'', which deals with the question of whether biology has anything particular to say about moral philosophy. Both Huxley and his grandson

* '' The Water Babies: A fairy tale for a land baby'' by

* '' The Water Babies: A fairy tale for a land baby'' by

* Huxley appears alongside Charles Darwin and Samuel Wilberforce in the play '' Darwin in Malibu'', written by Crispin Whittell, and is portrayed by

* Huxley appears alongside Charles Darwin and Samuel Wilberforce in the play '' Darwin in Malibu'', written by Crispin Whittell, and is portrayed by

Project Gutenberg

* Voorhees, Irving Wilson. ''The teachings of Thomas Henry Huxley''. Broadway, New York 1907. * Huxley, Thomas Henry. "Autobiography and Selected Essays". The Riverside Press Houghton Mifflin Company, Cambridge 1909.

Thomas H. Huxley

on the Embryo Project Encyclopedia

��Lists his publications, contains much of his writing. *

Huxley, Thomas Henry (1825–1895)

National Library of Australia, ''Trove, People and Organisation'' record for Thomas Huxley *

Science in the Making

Huxley's papers in the Royal Society's archives * * * Huxley review

Darwin on the origin of species

''

Time and life: Mr Darwin's "Origin of species."

''Macmillan's Magazine'' 1: 1859 p. 142–148. * Huxley review

Darwin on the origin of Species

''

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

and anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

who specialized in comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

.

The stories regarding Huxley's famous 1860 Oxford evolution debate

The 1860 Oxford evolution debate took place at the Oxford University Museum in Oxford, England, on 7 July 1860, seven months after the publication of Charles Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species''. Several prominent British scientists and philoso ...

with Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

were a key moment in the wider acceptance of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

and in his own career, although some historians think that the surviving story of the debate is a later fabrication. Huxley had been planning to leave Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

on the previous day, but, after an encounter with Robert Chambers, the author of '' Vestiges'', he changed his mind and decided to join the debate. Wilberforce was coached by Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, against whom Huxley also debated about whether humans were closely related to apes.

Huxley was slow to accept some of Darwin's ideas, such as gradualism

Gradualism, from the Latin ("step"), is a hypothesis, a theory or a tenet assuming that change comes about gradually or that variation is gradual in nature and happens over time as opposed to in large steps. Uniformitarianism, incrementalism, and ...

, and was undecided about natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, but despite this, he was wholehearted in his public support of Darwin. Instrumental in developing scientific education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

in Britain, he fought against the more extreme versions of religious tradition. Huxley coined the term "agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, the divine, or the supernatural is either unknowable in principle or unknown in fact. (page 56 in 1967 edition) It can also mean an apathy towards such religious belief and refer t ...

" in 1869 and elaborated on it in 1889 to frame the nature of claims in terms of what is knowable and what is not.

Huxley had little formal schooling and was virtually self-taught. He became perhaps the finest comparative anatomist

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

of the later 19th century. He worked on invertebrates

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordate subphylum ...

, clarifying relationships between groups previously little understood. Later, he worked on vertebrates

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

, especially on the relationship between apes and humans. After comparing ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird'') is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaîos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

'' with ''Compsognathus

''Compsognathus'' (; Ancient Greek, Greek ''kompsos''/κομψός; "elegant", "refined" or "dainty", and ''gnathos''/γνάθος; "jaw") is a genus of small, bipedalism, bipedal, carnivore, carnivorous theropoda, theropod dinosaur. Members o ...

'', he concluded that birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

evolved from small carnivorous dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

, a view now held by modern biologists.

The tendency has been for this fine anatomical work to be overshadowed by his energetic and controversial activity in favour of evolution, and by his extensive public work on scientific education, both of which had significant effects on society in Britain and elsewhere. Huxley's 1893 Romanes Lecture

The Romanes Lecture is a prestigious free public lecture given annually at the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, England.

The lecture series was founded by, and named after, the biologist George Romanes, and has been running since 1892. Over the years, ...

, "Evolution and Ethics", is exceedingly influential in China; the Chinese translation of Huxley's lecture even transformed the Chinese translation of Darwin's ''Origin of Species''.

Early life

Thomas Henry Huxley was born inEaling

Ealing () is a district in west London (sub-region), west London, England, west of Charing Cross in the London Borough of Ealing. It is the administrative centre of the borough and is identified as a major metropolitan centre in the London Pl ...

, then a village in Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

. He was the second youngest of eight children of George Huxley and Rachel Withers. His parents were members of the Church of England, but he sympathized with nonconformists. Like some other British scientists of the nineteenth century such as Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

, Huxley was brought up in a literate middle-class family which had fallen on hard times. His father was a mathematics schoolmaster

A schoolmaster, or simply master, is a male school teacher. The usage first occurred in England in the Late Middle Ages and early modern period. At that time, most schools were one-room or two-room schools and had only one or two such teacher ...

at Great Ealing School until it closed, putting the family into financial difficulties. As a result, Thomas left school at the age of 10, after only two years of formal schooling.

Despite this lack of formal schooling, Huxley was determined to educate himself. He became one of the great autodidact

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) or self-education (also self-learning, self-study and self-teaching) is the practice of education without the guidance of schoolmasters (i.e., teachers, professors, institutions).

Overview

Autodi ...

s of the nineteenth century. At first he read Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

's ''Geology'', and Hamilton

Hamilton may refer to:

* Alexander Hamilton (1755/1757–1804), first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States

* ''Hamilton'' (musical), a 2015 Broadway musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda

** ''Hamilton'' (al ...

's ''Logic''. In his teens, he taught himself German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, eventually becoming fluent and used by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

as a translator of scientific material in German. He learned Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, and enough Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

to read Aristotle in the original.

Later on, as a young adult, he made himself an expert, first teaching himself about invertebrates

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordate subphylum ...

, and later on vertebrates

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

. He did many of the illustrations for his publications on marine invertebrates. In his later debates and writing on science and religion, his grasp of theology was better than many of his clerical opponents.

He was apprenticed for short periods to several medical practitioners: at 13 to his brother-in-law John Cooke in Coventry, who passed him on to Thomas Chandler, notable for his experiments using mesmerism

Animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism, is a theory invented by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century. It posits the existence of an invisible natural force (''Lebensmagnetismus'') possessed by all living things, including humans ...

for medical purposes. Chandler's practice was in London's Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe ( ) is a district of South London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, with the Isle of Dogs to the ea ...

amidst the squalor endured by the Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by many as the great ...

ian poor. Afterward, another brother-in-law took him on: John Salt, his eldest sister's husband. Now aged 16, Huxley entered Sydenham College (behind University College Hospital

University College Hospital (UCH) is a teaching hospital in the Fitzrovia area of the London Borough of Camden, England. The hospital, which was founded as the North London Hospital in 1834, is closely associated with University College Lo ...

), a cut-price anatomy school. All this time Huxley continued his programme of reading, which more than made up for his lack of formal schooling.

A year later, buoyed by excellent results and a silver medal prize in the Apothecaries' yearly competition, Huxley was admitted to study at Charing Cross Hospital, where he obtained a small scholarship. At Charing Cross, he was taught by Thomas Wharton Jones

Thomas Wharton Jones (9 January 1808 – 7 November 1891) was a ophthalmologist and physiologist of the 19th century.

Biography

Jones's father was Richard Jones, a native of London. Richard Jones had moved north to St Andrews and was working w ...

, Professor of Ophthalmic Medicine and Surgery at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

. Jones had been Robert Knox's assistant when Knox bought cadavers from Burke and Hare. The young Wharton Jones, who acted as go-between, was exonerated of crime, but thought it best to leave Scotland. In 1845, under Wharton Jones' guidance, Huxley published his first scientific paper demonstrating the existence of a hitherto unrecognised layer in the inner sheath of hairs, a layer that has been known since as Huxley's layer. Later in life, Huxley organised a pension for his old mentor.

At twenty he passed his First M.B. examination at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a collegiate university, federal Public university, public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The ...

, winning the gold medal for anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

and physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

. However, he did not present himself for the final (Second M.B.) exams and consequently did not qualify for a university degree. His apprenticeships and exam results formed a sufficient basis for his application to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

.

Voyage of the ''Rattlesnake''

Aged 20, Huxley was too young to apply to theRoyal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

for a licence to practise, yet he was "deep in debt". So, at a friend's suggestion, he applied for an appointment in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. He had references on character and certificates showing the time spent on his apprenticeship and on requirements such as dissection and pharmacy. William Burnett, the Physician General of the Navy, interviewed him and arranged for the College of Surgeons to test his competence (by means of a ''viva voce

''Viva voce'' is a Latin phrase literally meaning "with living voice" but most often translated as "by word of mouth."

It may refer to:

*Word of mouth

*A voice vote in a deliberative assembly

*An oral exam

** Thesis defence, in academia

*Spoken ev ...

'').

Finally, Huxley was made Assistant Surgeon ('surgeon's mate', but in practice marine naturalist) to HMS ''Rattlesnake'', about to set sail on a voyage of discovery and surveying to New Guinea and Australia. The ''Rattlesnake'' left England on 3 December 1846 and, once it arrived in the southern hemisphere, Huxley devoted his time to the study of marine invertebrates. He began to send details of his discoveries back to England, where publication was arranged by Edward Forbes FRS (who had also been a pupil of Knox). Both before and after the voyage Forbes was something of a mentor to Huxley.

Huxley's paper "On the anatomy and the affinities of the family of Medusae" was published in 1849 by the

Finally, Huxley was made Assistant Surgeon ('surgeon's mate', but in practice marine naturalist) to HMS ''Rattlesnake'', about to set sail on a voyage of discovery and surveying to New Guinea and Australia. The ''Rattlesnake'' left England on 3 December 1846 and, once it arrived in the southern hemisphere, Huxley devoted his time to the study of marine invertebrates. He began to send details of his discoveries back to England, where publication was arranged by Edward Forbes FRS (who had also been a pupil of Knox). Both before and after the voyage Forbes was something of a mentor to Huxley.

Huxley's paper "On the anatomy and the affinities of the family of Medusae" was published in 1849 by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in its ''Philosophical Transactions''. Huxley united the Hydroid and Sertularian polyps with the Medusae to form a class to which he subsequently gave the name of ''Hydrozoa

Hydrozoa (hydrozoans; from Ancient Greek ('; "water") and ('; "animals")) is a taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class (biology), class of individually very small, predatory animals, some solitary and some colonial, most of which inhabit saline wat ...

''. The connection he made was that all the members of the class consisted of two cell layers, enclosing a central cavity or stomach. This is characteristic of the phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

now called the ''Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

''. He compared this feature to the serous and mucous structures of embryos of higher animals. When at last he got a grant from the Royal Society for the printing of plates, Huxley was able to summarise this work in ''The Oceanic Hydrozoa'', published by the Ray Society in 1859.

The value of Huxley's work was recognised and, on returning to England in 1850, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the following year, at the age of twenty-six, he not only received the Royal Society Medal but was also elected to the Council. He met

The value of Huxley's work was recognised and, on returning to England in 1850, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the following year, at the age of twenty-six, he not only received the Royal Society Medal but was also elected to the Council. He met Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

and John Tyndall

John Tyndall (; 2 August 1820 – 4 December 1893) was an Irish physicist. His scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the physical properties of air ...

, who remained his lifelong friends. The Admiralty retained him as a nominal assistant-surgeon, so he might work on the specimens he collected and the observations he made during the voyage of the ''Rattlesnake''. He solved the problem of '' Appendicularia'', whose place in the animal kingdom Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller (14 July 1801 – 28 April 1858) was a German physiologist, comparative anatomist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist, known not only for his discoveries but also for his ability to synthesize knowledge. The paramesonephri ...

had found himself wholly unable to assign. It and the Ascidians are both, as Huxley showed, tunicates, today regarded as a sister group to the vertebrates in the phylum ''Chordata

A chordate ( ) is a bilaterian animal belonging to the phylum Chordata ( ). All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five distinctive physical characteristics (Apomorphy and synapomorphy, synapomorphies) th ...

''. Other papers on the morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

of the cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

s and on brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum (biology), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear e ...

s and rotifer

The rotifers (, from Latin 'wheel' and 'bearing'), sometimes called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic Coelom#Pseudocoelomates, pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first describ ...

s are also noteworthy.

Later life

Following a lecture at the Royal Institution on 30 April 1852 Huxley indicated that it remained difficult to earn a living as a scientist alone. This was demonstrated in a letter written on 3 May 1852, where he states "Science in England does everything—but PAY. You may earn praise but not pudding". However, Huxley effectively resigned from the navy by refusing to return to active service, and in July 1854 he became professor of natural history at theRoyal School of Mines

The Royal School of Mines comprises the departments of Earth Science and Engineering, and Materials at Imperial College London. The Centre for Advanced Structural Ceramics and parts of the London Centre for Nanotechnology and Department of Bioe ...

and naturalist to the British Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance Earth science, geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research. ...

in the following year. In addition, he was Fullerian Professor at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

1855–1858 and 1865–1867; Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

1863–1869; president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

1869–1870; president of the Quekett Microscopical Club 1878; president of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

1883–1885; Inspector of Fisheries 1881–1885; and president of the Marine Biological Association 1884–1890. He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

in 1869.

The thirty-one years during which Huxley occupied the chair of natural history at the Royal School of Mines included work on vertebrate palaeontology and on many projects to advance the place of science in British life. Huxley retired in 1885, after a bout of depressive illness which started in 1884. He resigned the presidency of the Royal Society in mid-term, the Inspectorship of Fisheries, and his chair (as soon as he decently could) and took six months' leave. His pension was £1200 a year.

Huxley's London home, in which he wrote many of his works, was at 4 Marlborough Place,

Huxley's London home, in which he wrote many of his works, was at 4 Marlborough Place, St John's Wood

St John's Wood is a district in the London Borough of Camden, London Boroughs of Camden and the City of Westminster, London, England, about 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of Charing Cross. Historically the northern part of the Civil Parish#An ...

. The house was extended in the early 1870s to include a large drawing and dining room at which he held informal Sunday gatherings.

In 1890, he moved from London to Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. It is also a non-metropolitan district, local government district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, bor ...

, where he had purchased land in the Staveley Road upon which a house was built, 'Hodeslea', under the supervision of his son-in-law F. Waller. Here Huxley edited the nine volumes of his ''Collected Essays''. In 1894 he heard of Eugene Dubois' discovery in Java of the remains of ''Pithecanthropus erectus'' (now known as ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' ( ) is an extinction, extinct species of Homo, archaic human from the Pleistocene, spanning nearly 2 million years. It is the first human species to evolve a humanlike body plan and human gait, gait, to early expansions of h ...

'').

He died of a heart attack (after contracting influenza and pneumonia) in 1895 in Eastbourne, and was buried in London at East Finchley Cemetery. No invitations were sent out but two hundred people turned up for the funeral; they included

He died of a heart attack (after contracting influenza and pneumonia) in 1895 in Eastbourne, and was buried in London at East Finchley Cemetery. No invitations were sent out but two hundred people turned up for the funeral; they included Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

, William Henry Flower

Sir William Henry Flower (30 November 18311 July 1899) was an English surgeon, museum curator and comparative anatomist, who became a leading authority on mammals and especially on the primate brain. He supported Thomas Henry Huxley in an ...

, Mulford B. Foster, Edwin Lankester, Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 1827 – 10 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and pioneer of aseptic, antiseptic surgery and preventive healthcare. Joseph Lister revolutionised the Sur ...

, and apparently Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

. The family plot had been purchased upon the death of his eldest son Noel, who died of scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'', a Group A streptococcus (GAS). It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age. The signs and symptoms include a sore ...

in 1860; Huxley's wife Henrietta Anne and son Noel are also buried there.

Family

Huxley and his wife had five daughters and three sons: * Noel Huxley (1856–1860), died aged 3. * Jessie Oriana Huxley (1856–1927), married architect Fred Waller in 1877. * Marian Huxley (1859–1887), married artist John Collier in 1879. * Leonard Huxley (1860–1933), married Julia Arnold. * Rachel Huxley (1862–1934), married civil engineer Alfred Eckersley in 1884. * Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), married Harold Roller, travelled Europe as a singer. * Henry Huxley (1865–1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London. * Ethel Huxley (1866–1941) married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889.Public duties and awards

From 1870 onwards, Huxley was to some extent drawn away from scientific research by the claims of public duty. He served on eightRoyal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

s, from 1862 to 1884. From 1871 to 1880 he was a Secretary of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and from 1883 to 1885 he was president. He was president of the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

from 1868 to 1870. In 1870, he was president of the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

at Liverpool and, in the same year was elected a member of the newly constituted London School Board. He was president of the Quekett Microscopical Club from 1877 to 1879. He was the leading person amongst those who reformed the Royal Society, persuaded government about science, and established scientific education in British schools and universities.

He was awarded the highest honours then open to British men of science. The Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, who had elected him as Fellow when he was 25 (1851), awarded him the Royal Medal

The Royal Medal, also known as The Queen's Medal and The King's Medal (depending on the gender of the monarch at the time of the award), is a silver-gilt medal, of which three are awarded each year by the Royal Society. Two are given for "the mo ...

the next year (1852), a year before Charles Darwin got the same award. He was the youngest biologist to receive such recognition. Then later in life he received the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

in 1888 and the Darwin Medal

The Darwin Medal is one of the medals awarded by the Royal Society for "distinction in evolution, biological diversity and developmental, population and organismal biology".

In 1885, International Darwin Memorial Fund was transferred to the ...

in 1894; the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

awarded him the Wollaston Medal in 1876; the Linnean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collec ...

awarded him the Linnean Medal

The Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London was established in 1888, and is awarded annually to alternately a botanist or a zoologist or (as has been common since 1958) to one of each in the same year. The medal was of gold until 1976, and ...

in 1890. There were many other elections and appointments to eminent scientific bodies; these and his many academic awards are listed in the ''Life and Letters''. He turned down many other appointments, notably the Linacre chair in zoology at Oxford and the Mastership of University College, Oxford

University College, formally The Master and Fellows of the College of the Great Hall of the University commonly called University College in the University of Oxford and colloquially referred to as "Univ", is a Colleges of the University of Oxf ...

.

In 1873 the King of Sweden made Huxley, Hooker and Tyndall Knights of the Order of the Polar Star

The Royal Order of the Polar Star (Swedish language, Swedish: ''Kungliga Nordstjärneorden''), sometimes translated as the Royal Order of the North Star, is a Swedish order of chivalry created by Frederick I of Sweden, King Frederick I on 23 F ...

: they could wear the insignia but not use the title in Britain. Huxley collected many honorary memberships of foreign societies, academic awards and honorary doctorates from Britain and Germany. He also became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (, KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed in the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam.

In addition to various advisory a ...

in 1892. In 1916, a street in the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

was named in his honor (Huxley Avenue).

As recognition of his many public services, he was appointed Privy Councillor in 1892.

Despite his many achievements, he was given no award by the British state until late in life. In this, he did better than Darwin, who got no award of any kind from the state. (Darwin's proposed knighthood was vetoed by ecclesiastical advisers, including Wilberforce.) Perhaps Huxley had commented too often on his dislike of honours, or perhaps his many assaults on the traditional beliefs of organised religion made enemies in the establishment – he had vigorous debates in print with Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, and Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

, and his relationship with Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903), known as Lord Salisbury, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United ...

was less than tranquil.

Huxley was for about thirty years evolution's most effective advocate, and for some Huxley was "''the'' premier advocate of science in the nineteenth century orthe whole English-speaking world".

Though he had many admirers and disciples, his retirement and later death left British zoology somewhat bereft of leadership. He had, directly or indirectly, guided the careers and appointments of the next generation. Huxley thought he was "the only man who can carry out my work": The deaths of Balfour and W.K. Clifford were "the greatest losses to science in our time".

Vertebrate palaeontology

The first half of Huxley's career as a palaeontologist is marked by a rather strange predilection for 'persistent types', in which he seemed to argue that evolutionary advancement (in the sense of major new groups of animals and plants) was rare or absent in thePhanerozoic

The Phanerozoic is the current and the latest of the four eon (geology), geologic eons in the Earth's geologic time scale, covering the time period from 538.8 million years ago to the present. It is the eon during which abundant animal and ...

. In the same vein, he tended to push the origin of major groups such as birds and mammals back into the Palaeozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma at the start of ...

era, and to claim that no order of plants had ever gone extinct.

Much paper has been consumed by historians of science ruminating on this strange and somewhat unclear idea. Huxley was wrong to pitch the loss of orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* H ...

in the Phanerozoic as low as 7%, and he did not estimate the number of new orders which evolved. Persistent types sat rather uncomfortably next to Darwin's more fluid ideas; despite his intelligence, it took Huxley a surprisingly long time to appreciate some of the implications of evolution. However, gradually Huxley moved away from this conservative style of thinking as his understanding of palaeontology, and the discipline itself, developed.

Huxley's detailed anatomical work was, as always, first-rate and productive. His work on fossil fish shows his distinctive approach: Whereas pre-Darwinian naturalists collected, identified, and classified, Huxley worked mainly to reveal the evolutionary relationships between groups.

The lobe-finned fish

Sarcopterygii (; )—sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii ()—is a clade (traditionally a class or subclass) of vertebrate animals which includes a group of bony fish commonly referred to as lobe-finned fish. These vertebrates ar ...

(such as coelacanth

Coelacanths ( ) are an ancient group of lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii) in the class Actinistia. As sarcopterygians, they are more closely related to lungfish and tetrapods (the terrestrial vertebrates including living amphibians, reptiles, bi ...

s and lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the class Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, inc ...

) have paired appendages whose internal skeleton is attached to the shoulder or pelvis by a single bone, the humerus or femur. His interest in these fish brought him close to the origin of tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, one of the most important areas of vertebrate palaeontology.

The study of fossil reptiles led to his demonstrating the fundamental affinity of birds and reptiles, which he united under the title of ''Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

''. His papers on ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird'') is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaîos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

'' and the origin of birds

The scientific question of which larger group of animals birds evolved within has traditionally been called the "origin of birds". The present scientific consensus is that birds are a group of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs that originated du ...

were of great interest then and still are.

Apart from his interest in persuading the world that man was a primate and had descended from the same stock as the apes, Huxley did little work on mammals, with one exception. On his tour of America Huxley was shown the remarkable series of fossil horses, discovered by O. C. Marsh, in Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

's Peabody Museum. An Easterner, Marsh was America's first professor of palaeontology, but also one who had come west into hostile Indian territory in search of fossils, hunted buffalo, and met Red Cloud (in 1874). Funded by his uncle George Peabody, Marsh had made some remarkable discoveries: the huge Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

aquatic bird ''Hesperornis

''Hesperornis'' (meaning "western bird") is a genus of cormorant-like Ornithuran that spanned throughout the Campanian age, and possibly even up to the early Maastrichtian age, of the Late Cretaceous period. One of the lesser-known discoverie ...

'', and the dinosaur footprints along the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges into Long Isl ...

were worth the trip by themselves, but the horse fossils were really special. After a week with Marsh and his fossils, Huxley wrote excitedly, "The collection of fossils is the most wonderful thing I ever saw."

The collection at that time went from the small four-toed forest-dwelling '' Orohippus'' from the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

through three-toed species such as '' Miohippus'' to species more like the modern horse. By looking at their teeth he could see that, as the size grew larger and the toes reduced, the teeth changed from those of a browser to those of a grazer. All such changes could be explained by a general alteration in habitat from forest to grassland. And, it is now known, that is what did happen over large areas of North America from the Eocene to the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

: The ultimate causative agent was global temperature reduction (see Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum

The Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM), alternatively ”Eocene thermal maximum 1 (ETM1)“ and formerly known as the "Initial Eocene" or “Late Paleocene thermal maximum", was a geologically brief time interval characterized by a ...

). The modern account of the evolution of the horse

The evolution of the horse, a mammal of the family Equidae, occurred over a geologic time scale of 50 million years, transforming the small, dog-sized, forest-dwelling '' Eohippus'' into the modern horse. Paleozoologists have been able to piece ...

has many other members, and the overall appearance of the tree of descent is more like a bush than a straight line.

The horse series also strongly suggested that the process was gradual, and that the origin of the modern horse lay in North America, not in Eurasia. If so, then something must have happened to horses in North America, since none were there when Europeans arrived. The experience with Marsh was enough for Huxley to give credence to Darwin's gradualism, and to introduce the story of the horse into his lecture series.

Marsh's and Huxley's conclusions were initially quite different. However, Marsh carefully showed Huxley his complete sequence of fossils. As Marsh put it, Huxley "then informed me that all this was new to him and that my facts demonstrated the evolution of the horse beyond question, and for the first time indicated the direct line of descent of an existing animal. With the generosity of true greatness, he gave up his own opinions in the face of new truth, and took my conclusions as the basis of his famous New York lecture on the horse."

Support of Darwin

Huxley was originally not persuaded by "development theory", as evolution was once called. This can be seen in his savage review of Robert Chambers' ''

Huxley was originally not persuaded by "development theory", as evolution was once called. This can be seen in his savage review of Robert Chambers' ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tra ...

'', a book which contained some quite pertinent arguments in favour of evolution. Huxley had also rejected Lamarck's theory of transmutation, on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to support it. All this scepticism was brought together in a lecture to the Royal Institution, which made Darwin anxious enough to set about an effort to change young Huxley's mind. It was the kind of thing Darwin did with his closest scientific friends, but he must have had some particular intuition about Huxley, who was by all accounts a most impressive person even as a young man.

Huxley was therefore one of the small group who knew about Darwin's ideas before they were published (the group included Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

). The first publication by Darwin of his ideas came when Wallace sent Darwin his famous paper on natural selection, which was presented by Lyell and Hooker to the Linnean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collec ...

in 1858 alongside excerpts from Darwin's notebook and a Darwin letter to Asa Gray

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American botany, botanist of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana'' (1876) was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessaril ...

. Huxley's famous response to the idea of natural selection was "How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!" However, he never conclusively made up his mind about whether natural selection was the main method for evolution, though he did admit it was a hypothesis which was a good working basis.

Logically speaking, the prior question was whether evolution had taken place at all. It is to this question that much of Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' was devoted. Its publication in 1859 completely convinced Huxley of evolution and it was this and no doubt his admiration of Darwin's way of amassing and using evidence that formed the basis of his support for Darwin in the debates that followed the book's publication.

Huxley's support started with his anonymous favourable review of the ''Origin'' in the ''Times'' for 26 December 1859, and continued with articles in several periodicals, and in a lecture at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

in February 1860. At the same time, Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, whilst writing an extremely hostile anonymous review of the ''Origin'' in the ''Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'', also primed Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

who wrote one in the ''Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as ''The London Quarterly Review'', as reprinted by Leonard Scott, f ...

'', running to 17,000 words. The authorship of this latter review was not known for sure until Wilberforce's son wrote his biography. So it can be said that, just as Darwin groomed Huxley, so Owen groomed Wilberforce; and both the proxies fought public battles on behalf of their principals as much as themselves. Though we do not know the exact words of the Oxford debate, we do know what Huxley thought of the review in the ''Quarterly'':

SinceLord Brougham Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, (; 19 September 1778 – 7 May 1868) was a British statesman who became Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain and played a prominent role in passing the Reform Act 1832 and Slavery ...assailed Dr Young, the world has seen no such specimen of the insolence of a shallow pretender to a Master in Science as this remarkable production, in which one of the most exact of observers, most cautious of reasoners, and most candid of expositors, of this or any other age, is held up to scorn as a "flighty" person, who endeavours "to prop up his utterly rotten fabric of guess and speculation," and whose "mode of dealing with nature" is reprobated as "utterly dishonourable to Natural Science."

If I confine my retrospect of the reception of the ''Origin of Species'' to a twelvemonth, or thereabouts, from the time of its publication, I do not recollect anything quite so foolish and unmannerly as the ''Quarterly Review'' article...Since his death, Huxley has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog", taken to refer to his pluck and courage in debate, and to his perceived role in protecting the older man. The sobriquet appears to be Huxley's own invention, although of unknown date, and it was not current in his lifetime. While the second half of Darwin's life was lived mainly within his family, the younger and combative Huxley operated mainly out in the world at large. A letter from Huxley to Ernst Haeckel (2 November 1871) states: "The dogs have been snapping at arwin'sheels too much of late."

Debate with Wilberforce

Famously, Huxley responded to Wilberforce in the debate at theBritish Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

meeting, on Saturday 30 June 1860 at the Oxford University Museum. Huxley's presence there had been encouraged on the previous evening when he met Robert Chambers, the Scottish publisher and author of ''Vestiges'', who was walking the streets of Oxford in a dispirited state, and begged for assistance. The debate followed the presentation of a paper by John William Draper

John William Draper (May 5, 1811 – January 4, 1882) was an English polymath: a scientist, philosopher, physician, chemist, historian and photographer. He is credited with pioneering portrait photography (1839–40) and producing the first deta ...

, and was chaired by Darwin's former botany tutor John Stevens Henslow. Darwin's theory was opposed by the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

, and those supporting Darwin included Huxley and their mutual friends Hooker and Lubbock. The platform featured Brodie

Brodie can be a given name or a surname of Scottish origin, and a location in Moray, Scotland, its meaning is uncertain; it is not clear if Brodie, as a word, has its origins in the Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic or Pictish languages. In 2012 this nam ...

and Professor Beale, and Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

, who had been captain of HMS ''Beagle'' during Darwin's voyage, spoke against Darwin.

Wilberforce had a track record against evolution as far back as the previous Oxford B.A. meeting in 1847 when he attacked Chambers' ''Vestiges''. For the more challenging task of opposing the ''Origin'', and the implication that man descended from apes, he had been assiduously coached by Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

Owen stayed with him the night before the debate. On the day, Wilberforce repeated some of the arguments from his ''Quarterly Review'' article (written but not yet published), then ventured onto slippery ground. His famous jibe at Huxley (as to whether Huxley was descended from an ape on his mother's side or his father's side) was probably unplanned, and certainly unwise. Huxley's reply to the effect that he would rather be descended from an ape than a man who misused his great talents to suppress debatethe exact wording is not certainwas widely recounted in pamphlets and a spoof play.

The letters of Alfred Newton

Alfred Newton Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS HFRSE (11 June 18297 June 1907) was an England, English zoologist and ornithologist. Newton was Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Cambridge University from 1866 to 1907. Among his numerous public ...

include one to his brother giving an eyewitness account of the debate, and written less than a month afterwards. Other eyewitnesses, with one or two exceptions (Hooker especially thought ''he'' had made the best points), give similar accounts, at varying dates after the event. The general view was and still is that Huxley got much the better of the exchange, though Wilberforce himself thought he had done quite well. In the absence of a verbatim report, differing perceptions are difficult to judge fairly; Huxley wrote a detailed account for Darwin, a letter which does not survive; however, a letter to his friend Frederick Daniel Dyster does survive with an account just three months after the event. p. 313–330. A pro-Wilberforce account; lists many sources, but ''not'' Alfred Newton's letter to his brother. Many of Lucas's points are treated adversely in Jensen 1991, for example, note 77, p. 209.

One effect of the debate was to hugely increase Huxley's visibility amongst educated people, through the accounts in newspapers and periodicals. Another consequence was to alert him to the importance of public debate: a lesson he never forgot. A third effect was to serve notice that Darwinian ideas could not be easily dismissed: on the contrary, they would be vigorously defended against orthodox authority. A fourth effect was to promote professionalism in science, with its implied need for scientific education. A fifth consequence was indirect: as Wilberforce had feared, a defence of evolution did undermine literal belief in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

, especially the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

. Many of the liberal clergy at the meeting were quite pleased with the outcome of the debate; they were supporters, perhaps, of the controversial ''Essays and Reviews

''Essays and Reviews'', published by John William Parker in March 1860, is a Broad church, broad-church volume of seven essays on Christianity. The topics covered the biblical research of the German critics, the evidence for Christianity, religio ...

''. Thus, both on the side of science and on that of religion, the debate was important and its outcome significant. (see also below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

* Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

* Fred Belo ...

)

That Huxley and Wilberforce remained on courteous terms after the debate (and able to work together on projects such as the Metropolitan Board of Education) says something about both men, whereas Huxley and Owen were never reconciled.

Man's place in nature

For nearly a decade his work was directed mainly to the relationship of man to the apes. This led him directly into a clash withRichard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, a man widely disliked for his behaviour whilst also being admired for his capability. The struggle was to culminate in some severe defeats for Owen. Huxley's Croonian Lecture

The Croonian Medal and Lecture is a prestigious award, a medal, and lecture given at the invitation of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians.

Among the papers of William Croone at his death in 1684, was a plan to endow a singl ...

, delivered before the Royal Society in 1858 on ''The Theory of the Vertebrate Skull'' was the start. In this, he rejected Owen's theory that the bones of the skull and the spine were homologous, an opinion previously held by Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

and Lorenz Oken

Lorenz Oken (1 August 1779 – 11 August 1851) was a Germans, German natural history, naturalist, botany, botanist, biologist, and ornithology, ornithologist.

Biography

Oken was born Lorenz Okenfuss () in Bohlsbach (now part of Offenburg), Ortena ...

.

From 1860 to 1863 Huxley developed his ideas, presenting them in lectures to working men, students and the general public, followed by publication. Also in 1862 a series of talks to working men was printed lecture by lecture as pamphlets, later bound up as a little green book; the first copies went on sale in December. Other lectures grew into Huxley's most famous work ''Evidence as to Man's place in Nature'' (1863) where he addressed the key issues long before Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

published his '' Descent of Man'' in 1871.

Although Darwin did not publish his ''Descent of Man'' until 1871, the general debate on this topic had started years before (there was even a precursor debate in the 18th century between Monboddo and Buffon). Darwin had dropped a hint when, in the conclusion to the ''Origin'', he wrote: "In the distant future... light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history". Not so distant, as it turned out. A key event had already occurred in 1857 when Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

presented (to the Linnean Society) his theory that man was marked off from all other mammals by possessing features of the brain peculiar to the genus ''Homo''. Having reached this opinion, Owen separated man from all other mammals in a subclass of its own. No other biologist held such an extreme view. Darwin reacted "Man...as distinct from a chimpanzee san ape from a platypus... I cannot swallow that!" Neither could Huxley, who was able to demonstrate that Owen's idea was completely wrong.

The subject was raised at the 1860 BA Oxford meeting, when Huxley flatly contradicted Owen, and promised a later demonstration of the facts. In fact, a number of demonstrations were held in London and the provinces. In 1862 at the Cambridge meeting of the B.A. Huxley's friend William Flower gave a public dissection to show that the same structures (the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle and hippocampus minor) were indeed present in apes. The debate was widely publicised, and parodied as the '' Great Hippocampus Question''. It was seen as one of Owen's greatest blunders, revealing Huxley as not only dangerous in debate but also a better anatomist.

Owen conceded that there was something that could be called a hippocampus minor in the apes, but stated that it was much less developed and that such a presence did not detract from the overall distinction of simple brain size.

Huxley's ideas on this topic were summed up in January 1861 in the first issue (new series) of his own journal, the ''Natural History Review'': "the most violent scientific paper he had ever composed". This paper was reprinted in 1863 as chapter 2 of '' Man's Place in Nature'', with an addendum giving his account of the Owen/Huxley controversy about the ape brain. In his ''Collected Essays'' this addendum was removed.

The extended argument on the ape brain, partly in debate and partly in print, backed by dissections and demonstrations, was a landmark in Huxley's career. It was highly important in asserting his dominance of comparative anatomy, and in the long run more influential in establishing evolution amongst biologists than was the debate with Wilberforce. It also marked the start of Owen's decline in the esteem of his fellow biologists.

The following was written by Huxley to Rolleston before the BA meeting in 1861:

:"My dear Rolleston... The obstinate reiteration of erroneous assertions can only be nullified by as persistent an appeal to facts; and I greatly regret that my engagements do not permit me to be present at the British Association in order to assist personally at what, I believe, will be ''the seventh public demonstration during the past twelve months'' of the untruth of the three assertions, that the posterior lobe of the cerebrum, the posterior cornu of the lateral ventricle, and the hippocampus minor, are peculiar to man and do not exist in the apes. I shall be obliged if you will read this letter to the Section" Yours faithfully, Thos. H. Huxley.

During those years there was also work on human fossil anatomy and anthropology. In 1862 he examined the Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

skull-cap, which had been discovered in 1857. It was the first pre-''sapiens'' discovery of a fossil man, and it was immediately clear to him that the brain case was surprisingly large. Huxley also started to dabble in physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a natural science discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from ...

, and classified the human races into nine categories, along with placing them under four general categorisations as Australoid, Negroid, Xanthochroic and Mongoloid. Such classifications depended mainly on physical appearance and certain anatomical characteristics.

Natural selection