Thomas Dixon Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. (January 11, 1864 – April 3, 1946) was an American

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the

/nowiki>clerical robes">clerical_robes.html" ;"title="/nowiki>clerical robes">/nowiki>clerical robes/nowiki> in the hope of adding to my dignity on Sunday by the judicious use of dry goods."

In 1896 Dixon's ''Failure of Protestantism in New York and its causes'' appeared.

"Dixon decided to move on and form a new church, the People's Church (sometimes described as the People's Temple), in the auditorium of the Academy of Music;" this was a

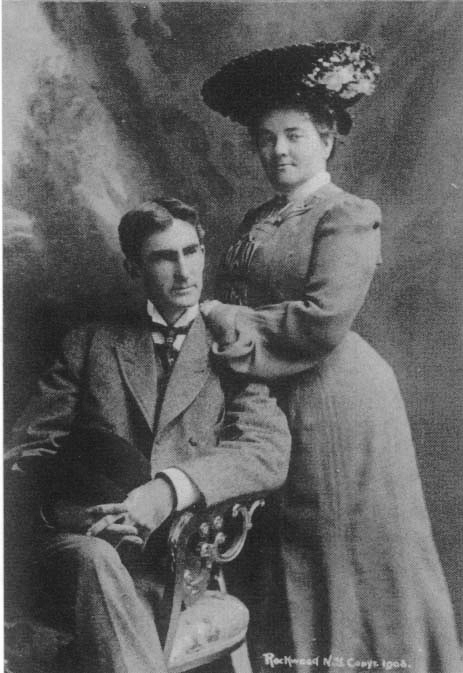

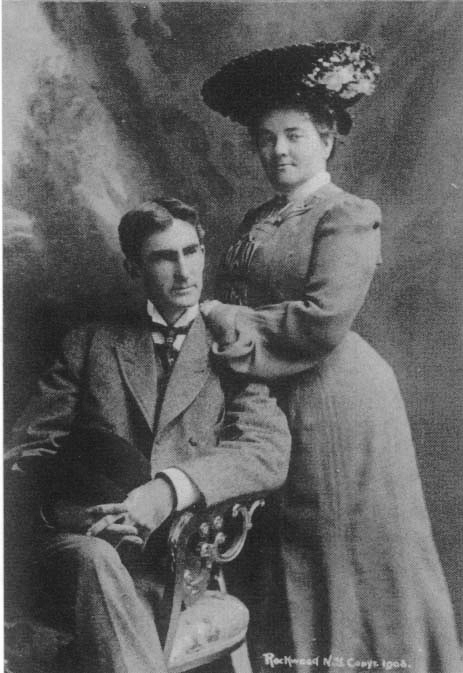

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to

''The Southerner: A Romance of the Real Lincoln''

(1913) (First of three novels on Southern heroes) * ''The Victim: A Romance of the Real

Text from FadedPage.Text from Project Gutenberg.Original pages, from Kentucky Digital Library.

* '' The Foolish Virgin: A Romance of Today'' (1915) (opposes emancipation of women) * '' The Fall of a Nation. A Sequel to The Birth of a Nation'' (1916)

''The Way of a Man. A Story of the New Woman''

(1918)

''The Man in Gray. A Romance of North and South''

(1921), on

''The Black Hood''

(1924) (on the Ku Klux Klan) * ''The Love Complex'' (1925). Based on ''The Foolish Virgin''. * ''The Sun Virgin'' (1929) (On

''A Man of the People. A Drama of Abraham Lincoln''

(1920). "The three-act drama dealt with the Republican National Committee's request that Lincoln stand down as candidate for president at the end of his first term in office and Lincoln's conflict with

IMDb cast list

''Living problems in religion and social science'' (sermons)

(1889) * ''What is religion? : an outline of vital ritualism : four sermons preached in Association Hall, New York, December 1890'' (1891)

''Dixon on Ingersoll. Ten discourses, delivered in Association Hall, New York. With a Sketch of the Author by Nym Crinkle''

(1892)

''The failure of Protestantism in New York and its causes''

(1896) * ''An open letter from Rev. Thomas Dixon to J.C. Beam. Read it.'' (self-published pamphlet, 1896?) * ''Dixon's sermons. Vol. i, no. i-v. i, no. 4. : a monthly magazine'' (1898) (Pamphlets on the Spanish–American War.) * ''The Free lance. Vol. i, no. 5-v. i, no. 9. : a monthly magazine'' (1898–1899) (Collection of five speeches, published in the magazine, on the

''Dixon's Sermons : Delivered in the Grand Opera House, New York, 1898-1899''

(1899)

''The Life Worth Living: A Personal Experience''

(1905) * ''The hope of the world; a story of the coming war'' (self-published pamphlet, 1925) * ''The Inside Story of the Harding Tragedy''. New York: The Churchill Company, 1932. With Harry M. Daugherty. * ''A dreamer in Portugal; the story of Bernarr Macfadden's mission to continental Europe'' (1934) * ''Southern Horizons : The Autobiography of Thomas Dixon'' (1984)

Historical Information from Historical Marker Database

* * * *

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Dixon, Thomas Jr. 1864 births 1946 deaths American people of Scottish descent American people of English descent 20th-century American novelists American male screenwriters Southern Baptist ministers Democratic Party members of the North Carolina House of Representatives North Carolina lawyers People from Shelby, North Carolina Wake Forest University alumni Novelists from North Carolina 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights American male novelists American segregationists Writers of American Southern literature American male dramatists and playwrights 19th-century American novelists Screenwriters from North Carolina Kappa Alpha Order Baptists from North Carolina Ku Klux Klan Race-related controversies in literature American Protestant ministers and clergy Johns Hopkins University alumni 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American screenwriters Neo-Confederates American lecturers American historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in the modern age American anti-communists Thomas American sermon writers 19th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers American male non-fiction writers 19th-century American male writers American pamphleteers

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

: a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister, politician, lawyer, lecturer, writer, and filmmaker. Dixon wrote two best-selling novels, '' The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' (1902) and '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), that romanticized Southern white supremacy, endorsed the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, opposed equal rights for black people, and glorified the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

as heroic vigilantes. Film director D. W. Griffith adapted ''The Clansman'' for the screen in ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'' is a 1915 American Silent film, silent Epic film, epic Drama (film and television), drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and ...

'' (1915). The film inspired the creators of the 20th-century rebirth of the Klan.

Early years

Dixon was born in Shelby, North Carolina, the son of Thomas Jeremiah Frederick Dixon Sr. and Amanda Elvira McAfee, daughter of a planter and slave-owner from York County, South Carolina. He was one of eight children, of whom five survived to adulthood. His elder brother, preacher Amzi Clarence Dixon, helped to edit '' The Fundamentals'', a series of articles (and later volumes) influential in fundamentalist Christianity. "He won international acclaim as one of the greatest ministers of his day." His younger brother Frank Dixon was also a preacher and lecturer. His sister, Elizabeth Delia Dixon-Carroll, became a pioneer woman physician in North Carolina and was the doctor for many years at Meredith College in Raleigh, N.C. Dixon's father, Thomas J. F. Dixon Sr., son of an English–Scottish father and a German mother, was a well-known Baptist minister and a landowner and slave-owner. His maternal grandfather, Frederick Hambright (possible namesake for the fictional North Carolina town of Hambright in which ''The Leopard's Spots'' takes place), was a German Palatine immigrant who fought in both the localmilitia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

and in the North Carolina Line of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

during the Revolutionary War. Dixon Sr. had inherited slaves and property through his first wife's father, which were valued at $100,000 in 1862.

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, during the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

period. The government confiscation of farmland, coupled with what Dixon saw as the corruption of local politicians, the vengefulness of Union troops, along with the general lawlessness of the period, all served to embitter him, and he became staunchly opposed to the reforms of Reconstruction.

Family involvement in the Ku Klux Klan

Dixon's father, Thomas Dixon Sr., and his maternal uncle, Col. Leroy McAfee, both joined the Klan early in the Reconstruction era with the aim of "bringing order" to the tumultuous times. McAfee was head of theKu Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

, North Carolina. "The romantic colonel made a lasting impression on the boy's imagination", and ''The Clansman'' was dedicated "To the memory of a Scotch-Irish leader of the South, my uncle, Colonel Leroy McAfee, Grand Titan of the Invisible Empire Ku Klux Klan". Dixon claimed that one of his earliest recollections was of a parade of the Ku Klux Klan through the village streets on a moonlit night in 1869, when Dixon was 5. Another childhood memory was of the widow of a Confederate soldier. She had served under McAfee accusing a black man of the rape of her daughter and seeking Dixon's family's help. Dixon's mother praised the Klan after it had hanged and shot the alleged rapist in the town square.Roberts, p. 202.

Education

In 1877, Dixon entered the Shelby Academy, where he earned a diploma in only two years. In September 1879, at the age of 15, Dixon followed his older brother and enrolled at the Baptist Wake Forest College, where he studied history and political science. As a student, Dixon performed remarkably well. In 1883, after only four years, he earned amaster's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

. His record at Wake Forest was outstanding, and he earned the distinction of achieving the highest student honors ever awarded at the university until then. As a student there, he was a founding member of the chapter of Kappa Alpha Order fraternity, and delivered the 1883 Salutatory Address with "wit, humor, pathos and eloquence".

"After his graduation from Wake Forest, Dixon received a scholarship to enroll in the political science program at Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

, "then the leading graduate school in the nation". There he met and befriended fellow student and future President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

. Wilson was also a Southerner, and Dixon says in his memoirs that "we became intimate friends.... I spent many hours with him in ilson's room" It is documented that Wilson and Dixon took at least one class together: "As a special student in history and politics he undoubtedly felt the influence of Herbert Baxter Adams and his circle of Anglo-Saxon historians, who sought to trace American political institutions back to the primitive democracy of the ancient Germanic tribes. The Anglo-Saxonists were staunch racists in their outlook, believing that only latter-day Aryan or Teutonic nations were capable of self-government." But after only one semester, despite the objections of Wilson, Dixon left Johns Hopkins to pursue journalism and a career on the stage.

Dixon headed to New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, and while he says in his autobiography that he enrolled briefly at an otherwise unknown Frobisher School of Drama, what he acknowledged publicly was his enrollment in a correspondence course given by the one-man American School of Playwriting, of William Thompson Price. Apparently as an advertisement for the school, he reproduced in the program his handwritten thank-you note.

As an actor, Dixon's physical appearance was a problem. He was but only , making for a very lanky appearance. One producer remarked that he would not succeed as an actor because of his appearance, but Dixon was complimented for his intelligence and attention to detail. The producer recommended that Dixon put his love for the stage into scriptwriting. Despite the compliment, Dixon returned home to North Carolina in shame.

Upon his return to Shelby, Dixon quickly realized that he was in the wrong place to begin to cultivate his playwriting skills. After the initial disappointment from his rejection, Dixon, with the encouragement of his father, enrolled in the short-lived Greensboro Law School, in Greensboro, North Carolina

Greensboro (; ) is a city in Guilford County, North Carolina, United States, and its county seat. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, its population was 299,035; it was estimated to be 307,381 in 2024. It is the List of municipalitie ...

. An excellent student, Dixon received his law degree in 1885.

Political career

It was during law school that Dixon's father convinced Thomas Jr. to enter politics. After graduation, Dixon ran for the local seat in theNorth Carolina General Assembly

The North Carolina General Assembly is the Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of the Government of North Carolina, state government of North Carolina. The legislature consists of two chambers: the North Carolina Senate, Senate and the North Ca ...

as a Democrat. Despite being only 20 years of age and too young to vote, he won the 1884 election by a 2-1 margin, a victory that was attributed to his eloquence.Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', p. 36; Gillespie, ''Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America'' Dixon retired from politics in 1886 after only one term in the legislature. He said that he was disgusted by the corruption and the backdoor deals of the lawmakers, and he is quoted as referring to politicians as "the prostitutes of the masses."Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', p. 38. However short, Dixon's political career gained him popularity throughout the South as he was the first to champion Confederate veterans' rights.Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', pp. 38-39.

Following his career in politics, Dixon practiced private law for a short time, but he found little satisfaction as a lawyer and soon left the profession to become a minister.

Dixon's thought

Dixon saw himself, and wanted to be remembered as, a man of ideas. He described himself as areactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

.

Dixon claimed to be a friend of black people, but he believed that they would never be the equal of whites, who he believed had superior intelligence; according to him, blacks could not benefit much even from the best education. He thought giving them the vote was a mistake, if not a disaster, and the Reconstruction Amendments were "insane".

He favored returning black people to Africa, although, by 1890, there were nearly 7.5 million black Americans; far too many people for this to be a realistic position.

Historian Albert Bushnell Hart indicates the implacability of Dixon's opposition to the advancement of blacks, quoting Dixon: "Make a negro a scientific and successful farmer, and let him plant his feet deep in your soil, and it will mean a race war."

In his autobiography, Dixon claims to have personally witnessed the following:

* The Freedmen's Bureau arrived in Shelby and told black people there that they could have " the franchise" (the vote), if they swore to support the constitutions of the United States and North Carolina. The black people then brought to their meetings with the agent enormous baskets, large jugs, huge bags, wheelbarrows, and wagons, as "all" thought "the franchise" was something tangible.

* He listened as a widow with her daughter told his uncle about the rape of the daughter by a black man whom Reconstruction governor William W. Holden had just pardoned and freed from prison. Dixon saw him lynched by the Klan.

* A Freedmen's Bureau agent told a former slave of Dixon's grandmother that he was free and could go where he pleased. The man did not want to leave, and when the agent kept repeating his message, threw a hatchet at him, which missed.

* In Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is List of municipalities in South Carolina, the second-mo ...

, about 1868, he saw "a black driver of a truck strike a little white boy of about six with a whip." The boy's mother rebuked the driver, for which she was arrested, and Dixon followed them into the courtroom, where a black magistrate fined her $10 for "insulting a freedman." His uncle and a friend paid the fine for her.

* When he was 7, the South Carolina House of Representatives had 94 black people and 30 white people; 23 of them not from South Carolina. When he visited at this time, he saw that some members were well dressed, "preachers in frock coats." However, "a lot" were "barefooted," "many" of them were "in overalls covered with red mud," and "the space behind the seats of the members was strewn with corks, broken bottles, stale crusts, greasy pieces of paper and bones picked clean." Without debate, the legislature voted the presiding officer receive $2000 for "the arduous duties...performed this week for the State." A page told Dixon that he was not receiving his $20 per day pay. The chamber "reek dof vile cigars and stale whisky," and "the odor of perspiring negroes," which he mentions twice. Karen Crowe finds his memories about this trip "particularly confused"; his chronology not being correct.

* During the elections of 1870, the Klan warned black people in North Carolina who could not read their ballot not to cast it. His uncle was their chief.

In addition, because his uncle was very involved in both the Klan and other local politics, residents funded him to go to Washington on their behalf. He received many reports about other alleged misconduct by black people and their white allies who controlled government in North Carolina.

Dixon had a particular hatred for Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens, leader in the House of Representatives, because he supported land confiscation from whites and its distribution to blacks (see 40 acres and a mule). According to Dixon, Stevens wanted "to make the South Negroid territory." Historians do not support many of his charges.

Dixon also opposed women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

. "His prejudices against women are more subtle." "For him, though a woman's real fulfillment lies most assuredly in marriage, the best example of that institution is one in which she takes an equal part."

Dixon was also concerned with threats of communism and war. "Civilization was threatened by socialists, by involvement of the U.S. in European affairs, finally, by communists... He saw civilization as a somewhat fragile quality thing threatened with wreck and ruin from all sides."

Minister

Dixon was ordained as aBaptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister on October 6, 1886. That month, church records show that he moved to the parsonage at 125 South John Street in Goldsboro, North Carolina, to serve as the Pastor of the First Baptist Church. Already a lawyer and fresh out of Wake Forest Seminary, life in Goldsboro must not have been what young Dixon had been expecting for a first preaching assignment. The social upheaval that Dixon portrays in his later works was largely melded through Dixon's experiences in the post-war Wayne County during Reconstruction.

On April 10, 1887, Dixon moved to the Second Baptist Church in Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most populous city in the state (after Charlotte, North Carolina, Charlotte) ...

. His popularity rose quickly, and before long, he was offered a position at the large Dudley Street Baptist Church (razed in 1964) in Roxbury, Boston

Roxbury () is a Neighborhoods in Boston, neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

Roxbury is a Municipal annexation in the United States, dissolved municipality and one of 23 official neighborhoods of Boston used by the city for ne ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. He was unpleasantly surprised to find prejudice there against black people; he always said he was a friend of black people. As his popularity on the pulpit grew, so did the demand for him as a lecturer. While preaching in Boston, Dixon was asked to give the commencement address at Wake Forest University. Additionally, he was offered a possible honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

from the university. Dixon himself rejected the offer, but he sang high praises about a then-unknown man Dixon believed deserved the honor, his old friend Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

. A reporter at Wake Forest who heard Dixon's praises of Wilson put a story on the national wire

file:Sample cross-section of high tension power (pylon) line.jpg, Overhead power cabling. The conductor consists of seven strands of steel (centre, high tensile strength), surrounded by four outer layers of aluminium (high conductivity). Sample d ...

, giving Wilson his first national exposure.

In August 1889, although his Boston congregation was willing to double his pay if he would stay, Dixon accepted a post in New York City. There he would preach at new heights, rubbing elbows with the likes of John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

(whom he helped in a campaign for New York governor). He had "the largest congregation of any Protestant minister in the United States." "As pastor of the Twenty-third Street Baptist Church in New York City…his audiences soon outgrew the church and, pending the construction of a new People's Temple, Dixon was forced to hold services in a neighboring YMCA." Thousands were turned away. John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

offered a $500,000 matching grant for Dixon's dream, "the building of a great temple". However, it never took place.

In 1895, Dixon resigned his position, saying that "for reaching of the non-church-going masses, I am convinced that the machinery of a strict Baptist church is a hindrance", and that he wished for "a perfectly free pulpit". The Board of the church had expressed to him three times their desire to leave Association Hall and return to the church's building; according to them, the crowds attending were not making enough donations to cover the Hall's rental, for which reason there was "a gradual increase of the indebtedness of the church, without any prospect for a change for the better." It was also reported at the time of his resignation that "For a long time past there have been dissensions among the members of the Twenty-Third street Baptist church, due to the objections of the more conservative members of the congregation to the 'sensational' character of the sermons preached during the last five years by the pastor, Rev. Thomas Dixon, Jr." A published letter from "An Old-Fashioned Clergyman" accused him of "sensationalism

In journalism and mass media, sensationalism is a type of editorial tactic. Events and topics in news stories are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers and viewers. This style of news reporting encourages biased or emoti ...

in the pulpit"; he responded that he was sensationalistic, but this was preferable to "the stupidity, failure, and criminal folly of tradition," an example of which was "putting on women's clothes nondenominational

A non-denominational person or organization is one that does not follow (or is not restricted to) any particular or specific religious denomination.

The term has been used in the context of various faiths, including Jainism, Baháʼí Faith, Zoro ...

church. He continued preaching there until 1899, when he began to lecture full-time.

When absent giving lectures, "the only man I could find who could hold my big crowd" was socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

Eugene V. Debs, whom Dixon speaks very highly of.

"While pastor of the People's church in New York he was once indicted on a charge of criminal libel for his pulpit attacks on city officials. When the warrant of arrest was served on him he set about looking up the records of the members of the grand jury which had indicted him. Then he denounced the jury from his pulpit. The proceedings were dropped."

Lecturer

Dixon was someone "who had something to say to the world and meant to say it." He had "something burning in his heart for utterance." He insisted repeatedly that he was only telling the truth, furnished documentation when challenged, and asked his critics to point out any untruths in his works, even announcing a reward for anyone who could. The reward was not claimed. Dixon enjoyed lecturing, and found it "an agreeable pastime". "Success on the platform was the easiest thing I ever tried." He went on theChautauqua

Chautauqua ( ) is an adult education and social movement in the United States that peaked in popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Cha ...

circuit, and was often hailed as the best lecturer in the nation. He tells us in his autobiography that as a lecturer, "I always spoke without notes after careful preparation". Over four years he was heard by an estimated 5,000,000 attendees, sometimes exceeding 6,000 at a single program. He gained an immense following throughout the country, particularly in the South, where he played up his speeches on the plight of the working man and what he called the horrors of Reconstruction.

About 1896, Dixon had a breakdown caused by overwork. He had lived on 94th St. in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

and on Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

, but did not like the weather, "and the doctor had come to see us every week". The doctor said he should "live in the country". Now wealthy, in 1897 Dixon purchased "a stately colonial home, Elmington Manor", in Gloucester County, Virginia. The house had 32 rooms and the grounds were . He had his own post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letter (message), letters and parcel (package), parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post o ...

, Dixondale. The same year he had an steam yacht built, which required a crew of "two men and a boy"; he named it Dixie. He says in his autobiography that one year he paid income tax on $210,000. "I felt...I had more money than I could possibly spend."

Becoming a novelist

It was during such a lecture tour that Dixon attended a theatrical version ofHarriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

's ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two Volume (bibliography), volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans ...

''. Dixon could hardly contain his anger and outrage at the play, and it is said that he literally "wept at he play'smisrepresentation of southerners." Dixon vowed that the "true story" of the South should be told. As a direct result of that experience, Dixon wrote his first novel, '' The Leopard's Spots'' (1902), which uses several characters, including Simon Legree, recycled from Stowe's novel. It and its successor, '' The Clansman'', were published by Doubleday, Page & Company (and contributed significantly to the publisher's success). Dixon turned to Doubleday because he had a "long friendship" with fellow North Carolinian Walter Hines Page. Doubleday accepted ''The Leopard's Spots'' immediately. The entire first edition was sold before it was printed—"an unheard of thing for a first novel". It sold over 100,000 copies in the first 6 months, and the reviews were "generous beyond words".

Dixon as novelist

Dixon turned to writing books as a way to present his ideas to an even larger audience. Dixon's "Trilogy of Reconstruction" consisted of '' The Leopard's Spots'' (1902), '' The Clansman'' (1905), and '' The Traitor'' (1907). (In his autobiography, he says that in creating trilogies, he was following the model of Polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz.) Dixon's novels were best-sellers in their time, despite beingracist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

pastiches of historical romance

Historical romance is a broad category of mass-market fiction focusing on romantic relationships in historical periods, which Lord Byron, Byron helped popularize in the early 19th century. The genre often takes the form of the novel.

Varieties

...

fiction. They glorify an antebellum American South white supremacist viewpoint. Dixon claimed to oppose slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, but he espoused racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

and vehemently opposed universal suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and miscegenation. He was "a spokesman for southern Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

segregation and for American racism in general. Yet he did nothing more than reiterate the comments of others."

Dixon's Reconstruction-era novels depict Northerners as greedy carpetbaggers and white Southerners as victims. Dixon's ''Clansman'' caricatures the Reconstruction as an era of "black rapists" and "blonde-haired" victims, and if his racist opinions were unknown, the vile and gratuitous brutality and Klan terror in which the novel revels might be read as satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposin ...

. If "Dixon used the motion picture as a propaganda tool for his often outrageous opinions on race, communism, socialism, and feminism," D. W. Griffith, in his movie adaptation of the novel, ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'' is a 1915 American Silent film, silent Epic film, epic Drama (film and television), drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and ...

'' (1915), is a case in point. Dixon wrote a highly successful stage adaptation of ''The Clansman'' in 1905. In ''The Leopard's Spots'', the Reverend Durham character indoctrinates Charles Gaston, the protagonist, with a foul-mouthed diatribe of hate speech

Hate speech is a term with varied meaning and has no single, consistent definition. It is defined by the ''Cambridge Dictionary'' as "public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as ...

. Equally, Dixon's opposition to miscegenation seemed to be as much about confused sexism as it was about racism, as he opposed relationships between white women and black men but not between black women and white men.

Another pet hate for Dixon and the focus of another trilogy was socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

: '' The One Woman: A Story of Modern Utopia'' (1903), '' Comrades: A Story of Social Adventure in California'' (1909), and '' The Root of Evil'' (1911), the latter of which also discusses some of the problems involved in modern industrial capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

. The book ''Comrades'' was made into a motion picture, entitled '' Bolshevism on Trial'', released in 1919.

Dixon wrote 22 novels, as well as many plays, sermons, and works of non-fiction. W.E.B. DuBois said he was more widely read than Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

. His writing centered on three major themes: racial purity, the evils of socialism, and the traditional family role of woman as wife and mother. (Dixon opposed female suffrage.) A common theme found in his novels is violence against white women, mostly by Southern black men. The crimes are almost always avenged through the course of the story, the source of which might stem from a belief of Dixon's that his mother had been sexually abused as a child. He wrote his last novel, '' The Flaming Sword'', in 1939 and not long after was disabled by a cerebral hemorrhage.Gillespie, ''Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America''; Davenport, F. Garvin. ''Journal of Southern History'', August 1970.

While ''The Birth of a Nation'' is still viewed for its crucial role in the birth of the feature film

A feature film or feature-length film (often abbreviated to feature), also called a theatrical film, is a film (Film, motion picture, "movie" or simply “picture”) with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole present ...

, none of Dixon's novels have stood the test of time. When ''Publishers Weekly

''Publishers Weekly'' (''PW'') is an American weekly trade news magazine targeted at publishers, librarians, booksellers, and literary agents. Published continuously since 1872, it has carried the tagline, "The International News Magazine of ...

'' listed the best-selling fiction of the last quarter century, none of Dixon's books was included.

Dixon as playwright

After the successful publication of ''The Clansman'' Dixon proceeded to adapt it for the stage. It opened inNorfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

on September 22, 1905, and toured the south with great commercial success before venturing into receptive northern markets such as Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

. One Dixon biographer, reviewing the script, noted its conspicuous gaps in character and plot development. No background or justification is offered for Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Klan or the institution of lynching, but the play nonetheless excited the passions of southern audiences that took these for granted. Contemporary newspaper and religious criticism, even in the south, was less favorable. Journalists called the play a "riot breeder" and an "exhibition of hysterics" while an Atlanta Baptist minister denounced it as a slander on white southerners as well as black. ''The Clansman'' played in New York in 1906, again to an enthusiastic audience and critical panning, while Dixon gave speeches around the city and unsuccessfully offered Booker T. Washington a bribe to repudiate racial equality.

Dixon created other plays through 1920, both adapted and original. All of them continued his racial and sectional themes except for the 1919 anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

drama ''The Red Dawn''. His 1910 miscegenation drama ''The Sins of the Father'' struggled after its initial run in Norfolk. Dixon took over as the lead actor (later stating, dubiously, that the original actor was killed by a shark) and performed for a thirty-week tour. According to Dixon family tradition his stage talent was inadequate, and the play failed to find a venue in New York. He stated that all of his racial dramas were intended to prove that coexistence was impossible and that separation was the only solution.

Dixon as filmmaker

Turning ''The Clansman'' into a movie was the next step, reaching more people with even more impact. As he said ''à propos'' of '' The Fall of a Nation'' (1916): the movie "reached more than thirty million people and was, therefore, thirty times more effective than any book I might have written."Attitudes towards the revived Klan

Dixon was an extremenationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

, chauvinist, racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

, reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

ideologue, although "at the height of his fame, Dixon might well have been considered a liberal by many." He spoke favorably several times of Jews and Catholics. He distanced himself from the "bigotry" of the revived "second era" Ku Klux Klan, which he saw as "a growing menace to the cause of law and order", and its members "unprincipled marauders" (and they in turn attacked Dixon). It seems that he inferred that the "Reconstruction Klan" members were not bigots. "He condemned the secret organization for ignoring civilized government and encouraging riot

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

, bloodshed, and anarchy." He denounced antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

as "idiocy", pointing out that the mother of Jesus was Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. "The Jewish race Is the most persistent, powerful, commercially successful race that the world has ever produced." While lauding the "loyalty and good citizenship" of Catholics, he claimed it was the "duty of whites to lift up and help" the supposedly "weaker races."

Family

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama. Named for Continental Army major general Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River on the Gulf Coastal Plain. The population was 2 ...

after Bussey's father refused to give his consent to the marriage.Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', p. 39.

Dixon and Harriet Bussey had three children together: Thomas III, Louise, and Jordan.

Final years

Dixon's final years were not financially comfortable. "He had lost his house on Riverside Drive in New York, which he had occupied for twenty-five years.... His books no longer became...best sellers." The money he earned from his first books he lost on the stock and cotton exchanges in the crash of 1907. "His final venture in the late 1920s was a vacation resort," Wildacres Retreat, in Little Switzerland, North Carolina. "After he had spent a vast amount of money on its development, the enterprise collapsed as speculative bubbles in land across the country began to burst before the crash of 1929." He ended his career as an impoverished court clerk in Raleigh, North Carolina. Harriet died on December 29, 1937, and fourteen months later, on February 26, 1939, Dixon had a debilitating cerebral hemorrhage. Less than a month later, from his hospital bed, Dixon married Madelyn Donovan, an actress thirty years his junior, who had played a role in a film adaptation of ''Mark of the Beast''. She had also been his research assistant on ''The Flaming Sword'', his last novel. The marriage "induced indignation and outrage among his remaining relatives", who viewed her as a "bad woman". She cared for him for the next seven years, taking over his duties as clerk when he could no longer work. He tried to provide for her future financial security, giving her the rights to all his property. He says nothing about her in his autobiography. Dixon died on April 3, 1946. He is buried, with Madelyn, in Sunset Cemetery in Shelby, North Carolina.Archival material

The Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. Collection, in the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, contains documents, manuscripts, biographical works, and other materials pertaining to the life and literary career of Thomas Dixon. It also holds fifteen hundred volumes from Dixon's personal book collection and nine paintings which became illustrations in his novels. Additional archival material is in the Duke University Library.List of works

Novels

* '' The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' (1902) (Part 1 of the trilogy on Reconstruction) * '' The One Woman: A Story of Modern Utopia'' (1903) (Part 1 of the trilogy on socialism) * '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905) (Part 2 of the trilogy on Reconstruction) * '' The Traitor: A Story of the Fall of the Invisible Empire'' (1907) (Part 3 of the trilogy on Reconstruction) * '' Comrades: A Story of Social Adventure in California'' (1909) (Part 2 of the trilogy on socialism) * '' The Root of Evil'' (1911) (Part 3 of the trilogy on socialism) An attack on capitalism * '' The Sins of the Father: A Romance of the South'' (1912), on miscegenation''The Southerner: A Romance of the Real Lincoln''

(1913) (First of three novels on Southern heroes) * ''The Victim: A Romance of the Real

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

'' (1914) (Second of three novels on Southern heroesText from FadedPage.

* '' The Foolish Virgin: A Romance of Today'' (1915) (opposes emancipation of women) * '' The Fall of a Nation. A Sequel to The Birth of a Nation'' (1916)

''The Way of a Man. A Story of the New Woman''

(1918)

''The Man in Gray. A Romance of North and South''

(1921), on

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

(Third of three novels on Southern heroes)

''The Black Hood''

(1924) (on the Ku Klux Klan) * ''The Love Complex'' (1925). Based on ''The Foolish Virgin''. * ''The Sun Virgin'' (1929) (On

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish ''conquistador'', best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire.

Born in Trujillo, Cáceres, Trujillo, Spain, to a poor fam ...

.)

* ''Companions'' (1931) (Based on The One Woman.)

* '' The Flaming Sword'' (1939), on the dangers of Communism for the United States (in the novel, Communists take over the country)

Theater

* ''From College to Prison'', play, ''Wake Forest Student'', January 1883. * '' The Clansman'' (1905). Produced by George H. Brennan. Multiple touring companies simultaneously. * '' The Traitor'' (1908), written in collaboration with Channing Pollock, whose name got first billing over that of Dixon * '' The Sins of the Father'' (1909) Antedates 1912 publication of the novel. Dixon toured playing a main part after the actor was killed. "The Dixon family was of the opinion that he was absolutely lousy on stage." * '' Old Black Joe'', one act (1912) * ''The Almighty Dollar'' (1912) * '' The Leopard's Spots'' (1913) * ''The One Woman'' (1918) * ''The Invisible Foe'' (1918). Written by Walter Hackett; produced and directed by Dixon. * ''The Red Dawn: A Drama of Revolution'' (1919, unpublished) * ''Robert E. Lee'', a play in five acts (1920)''A Man of the People. A Drama of Abraham Lincoln''

(1920). "The three-act drama dealt with the Republican National Committee's request that Lincoln stand down as candidate for president at the end of his first term in office and Lincoln's conflict with

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

. The third-act climax had Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee receiving news of General Sherman's capture of Atlanta. Lincoln reappeared in the epilogue to deliver his second inaugural address." According to IMDb

IMDb, historically known as the Internet Movie Database, is an online database of information related to films, television series, podcasts, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and biograp ...

, it had only 15 performancesIMDb cast list

Cinema

* ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'' is a 1915 American Silent film, silent Epic film, epic Drama (film and television), drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and ...

'' (1915)

* '' The Fall of a Nation'' (1916) (lost)

* '' The Foolish Virgin'' (1916)

* ''The One Woman'' (1918)

* '' Bolshevism on Trial'', based on ''Comrades'' (1919)

* '' Wing Toy'' (1921) (lost)

* '' Where Men Are Men'' (1921)

* '' Bring Him In'' (1921) "Based on a story by H. H. Van Loan."

* '' Thelma'' (1922)

* ''The Mark of the Beast'' (1923) The only film Dixon directed as well as wrote and produced. It is equally important for bringing Madelyn Donovan openly into his life.

* '' The Brass Bowl'' (1924) "Based on the novel by Louis Joseph Vance."

* ''The Great Diamond Mystery'' (1924) "Based on a story by Shannon Fife."

* ''The Painted Lady'' (1924) "Based on the Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine published six times a year. It was published weekly from 1897 until 1963, and then every other week until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely circulated and influ ...

story by Larry Evans."

* '' The Foolish Virgin'' (1924) (lost)

* '' Champion of Lost Causes'' (1925) "Based on the ''Flynn's'' magazine story by Max Brand."

* '' The Trail Rider'' (1925) "Based on the novel by George Washington Ogden."

* '' The Gentle Cyclone'' (1926) "Based on the Western Story Magazine story "Peg Leg and Kidnapper" by Frank R. Buckley."

* ''The torch; a story of the paranoiac who caused a great war'' (screenplay, self-published, 1934). On John Brown, who Dixon presents as a madman, receiving "most of the blame for having touched off the 'powder keg' that caused the Civil War."

* '' Nation Aflame'' (1937)

Non-fiction

''Living problems in religion and social science'' (sermons)

(1889) * ''What is religion? : an outline of vital ritualism : four sermons preached in Association Hall, New York, December 1890'' (1891)

''Dixon on Ingersoll. Ten discourses, delivered in Association Hall, New York. With a Sketch of the Author by Nym Crinkle''

(1892)

''The failure of Protestantism in New York and its causes''

(1896) * ''An open letter from Rev. Thomas Dixon to J.C. Beam. Read it.'' (self-published pamphlet, 1896?) * ''Dixon's sermons. Vol. i, no. i-v. i, no. 4. : a monthly magazine'' (1898) (Pamphlets on the Spanish–American War.) * ''The Free lance. Vol. i, no. 5-v. i, no. 9. : a monthly magazine'' (1898–1899) (Collection of five speeches, published in the magazine, on the

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

.)

''Dixon's Sermons : Delivered in the Grand Opera House, New York, 1898-1899''

(1899)

''The Life Worth Living: A Personal Experience''

(1905) * ''The hope of the world; a story of the coming war'' (self-published pamphlet, 1925) * ''The Inside Story of the Harding Tragedy''. New York: The Churchill Company, 1932. With Harry M. Daugherty. * ''A dreamer in Portugal; the story of Bernarr Macfadden's mission to continental Europe'' (1934) * ''Southern Horizons : The Autobiography of Thomas Dixon'' (1984)

Articles

* *References

Bibliography

* Republished from * * * * *McGee, Brian R. "The Argument from Definition Revised: Race and Definition in the Progressive Era", pp. 141–158, ''Argumentation and Advocacy'', Vol. 35 (1999) *Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. ''Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1986-1920.'' Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996. *Williamson, Joel. ''A Rage for Order: Black-White Relations in the American South Since Emancipation'', Oxford, 1986. * * * *External links

Historical Information from Historical Marker Database

* * * *

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Dixon, Thomas Jr. 1864 births 1946 deaths American people of Scottish descent American people of English descent 20th-century American novelists American male screenwriters Southern Baptist ministers Democratic Party members of the North Carolina House of Representatives North Carolina lawyers People from Shelby, North Carolina Wake Forest University alumni Novelists from North Carolina 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights American male novelists American segregationists Writers of American Southern literature American male dramatists and playwrights 19th-century American novelists Screenwriters from North Carolina Kappa Alpha Order Baptists from North Carolina Ku Klux Klan Race-related controversies in literature American Protestant ministers and clergy Johns Hopkins University alumni 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American screenwriters Neo-Confederates American lecturers American historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in the modern age American anti-communists Thomas American sermon writers 19th-century American non-fiction writers 20th-century American non-fiction writers American male non-fiction writers 19th-century American male writers American pamphleteers