Thomas Blamey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Blamey was transferred to the

Following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Blamey was transferred to the

On the night of 13 May 1915, Blamey, in his capacity as 1st Division intelligence officer, led a patrol consisting of himself,

On the night of 13 May 1915, Blamey, in his capacity as 1st Division intelligence officer, led a patrol consisting of himself,

In 1923, the

In 1923, the  Blamey was re-appointed as Chief Commissioner in 1930 but at a reduced salary of £A1,250 per annum, equivalent to in . A year later it was reduced still further, to £A785, equivalent to in , due to cutbacks as a result of the

Blamey was re-appointed as Chief Commissioner in 1930 but at a reduced salary of £A1,250 per annum, equivalent to in . A year later it was reduced still further, to £A785, equivalent to in , due to cutbacks as a result of the

Citation: "Major General Thomas Albert Blamey, C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O. Chief Commissioner of Police, State of Victoria. For services in connection with the Centenary Celebrations." Noted that Blamey has received his knighthood by

On 13 October 1939, a month after the outbreak of the Second World War, Blamey was promoted to lieutenant general, and appointed to command the 6th Division, the first formation of the new Second Australian Imperial Force, and received the AIF service number VX1. Menzies limited his choice of commanders by insisting that they be selected from the Militia rather than the Permanent Military Forces (PMF), the Army's full-time, regular component. For brigade commanders he chose

On 13 October 1939, a month after the outbreak of the Second World War, Blamey was promoted to lieutenant general, and appointed to command the 6th Division, the first formation of the new Second Australian Imperial Force, and received the AIF service number VX1. Menzies limited his choice of commanders by insisting that they be selected from the Militia rather than the Permanent Military Forces (PMF), the Army's full-time, regular component. For brigade commanders he chose  I Corps assumed responsibility for the front in

I Corps assumed responsibility for the front in

The Allied command structure was soon put under strain by Australian reverses in the Kokoda Track campaign. MacArthur was highly critical of the Australian performance, and confided to the

The Allied command structure was soon put under strain by Australian reverses in the Kokoda Track campaign. MacArthur was highly critical of the Australian performance, and confided to the

The next operation was MacArthur's

The next operation was MacArthur's  Frank Forde criticised Blamey for having too many generals. Blamey could only reply that the Australian Army had one general for 15,741 men and women compared to one per 9,090 in the British Army.

Blamey was annoyed by the media campaign run against him by William Dunstan and Keith Murdoch of ''

Frank Forde criticised Blamey for having too many generals. Blamey could only reply that the Australian Army had one general for 15,741 men and women compared to one per 9,090 in the British Army.

Blamey was annoyed by the media campaign run against him by William Dunstan and Keith Murdoch of ''

On 5 April 1944, Blamey departed for San Francisco on board for the first leg of a voyage to attend the 1944

On 5 April 1944, Blamey departed for San Francisco on board for the first leg of a voyage to attend the 1944

Menzies became prime minister again in December 1949, and he resolved that Blamey should be promoted to the rank of field marshal, something that had been mooted in 1945. The recommendation went via the

Menzies became prime minister again in December 1949, and he resolved that Blamey should be promoted to the rank of field marshal, something that had been mooted in 1945. The recommendation went via the

Blamey is honoured in Australia in various ways, including a square named after him which is situated outside the

Blamey is honoured in Australia in various ways, including a square named after him which is situated outside the

Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Sir Thomas Albert Blamey (24 January 1884 – 27 May 1951) was an Australian general of the First and Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

s. He is the only Australian to attain the rank of field marshal.

Blamey joined the Australian Army as a regular soldier in 1906, and attended the Staff College at Quetta. During the First World War, he participated in the landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915, and served as a staff officer in the Gallipoli campaign, where he was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

for a daring raid behind enemy lines. He later served on the Western Front, where he distinguished himself in the planning for the Battle of Pozières. He rose to the rank of brigadier general, and served as chief of staff of the Australian Corps under Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

Sir John Monash

General (Australia), General Sir John Monash (; 27 June 1865 – 8 October 1931) was an Australian civil engineer and military commander of the World War I, First World War. He commanded the 13th Brigade (Australia), 13th Infantry Brigade befor ...

, who credited him as a factor in the Corps' success in the Battle of Hamel, the Battle of Amiens and the Battle of the Hindenburg Line.

After the war Blamey became the Deputy Chief of the General Staff, and was involved in the creation of the Royal Australian Air Force

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is the principal Air force, aerial warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Army. Constitutionally the Governor-Gener ...

. He resigned from the regular Army in 1925 to become Chief Commissioner of the Victoria Police

Victoria Police is the primary law enforcement agency of the Australian States and territories of Australia, state of Victoria (Australia), Victoria. It was formed in 1853 and currently operates under the ''Victoria Police Act 2013''.

, Victor ...

, but remained in the Militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

, rising to command the 3rd Division in 1931. As chief commissioner, Blamey set about dealing with the grievances that had led to the 1923 Victorian police strike

The 1923 Victorian police strike occurred in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. In November 1923, on the eve of the Melbourne Spring Racing Carnival, half the police force in Melbourne police strike, went on strike over the operation of a superviso ...

, and implemented innovations such as police dogs and equipping vehicles with radios. His tenure as chief commissioner was marred by a scandal in which his police badge was found in a brothel

A brothel, strumpet house, bordello, bawdy house, ranch, house of ill repute, house of ill fame, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activity with prostitutes. For legal or cultural reasons, establis ...

, and a later attempt to cover up the shooting of a police officer led to his forced resignation in 1936.

During the Second World War Blamey commanded the Second Australian Imperial Force and the I Corps in the Middle East. In the latter role he commanded Australian and Commonwealth troops in the disastrous Battle of Greece

The German invasion of Greece or Operation Marita (), were the attacks on Greece by Italy and Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usually known as the Greco-Italian War, was followed by the German invasi ...

. He attempted to protect Australian interests against British commanders who sought to disperse his forces. He was appointed deputy commander-in-chief of Middle East Command, and was promoted to general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in 1941. In 1942, he returned to Australia as commander-in-chief of the Australian Military Forces and commander of Allied Land Forces in the South West Pacific Area under American General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

. On the orders of MacArthur and Prime Minister John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), having been most ...

, he assumed personal command of New Guinea Force during the Kokoda Track campaign, and relieved Lieutenant General Sydney Rowell under controversial circumstances. He planned and carried out the significant and victorious Salamaua–Lae campaign but during the final campaigns of the war he faced criticism of the Army's performance. He signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on behalf of Australia at Japan's ceremonial surrender in Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan spanning the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture, on the southern coast of the island of Honshu. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. Th ...

on 2 September 1945, and personally accepted the Japanese surrender on Morotai on 9 September.

Early life

The seventh of ten children, Blamey was born on 24 January 1884 in Lake Albert, nearWagga Wagga

Wagga Wagga (; informally called Wagga) is a major regional city in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia. Straddling the Murrumbidgee River, with an urban population of more than 57,003 as of 2021, it is an important agricultural, m ...

, New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

. He was the son of Richard Blamey, a farmer who had emigrated from Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

at the age of 16 in 1862, and his Australian-born wife, Margaret (née Murray). After farming failures in Queensland and on the Murrumbidgee River

The Murrumbidgee River () is a major tributary of the Murray River within the Murray–Darling basin and the second longest river in Australia. It flows through the Australian state of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, desce ...

near Wagga Wagga, his father Richard moved to a small property in Lake Albert, where he supplemented his farm income working as a drover and shearing overseer.

Blamey acquired the bush skills associated with his father's enterprises and became a sound horseman. He attended Wagga Wagga Superior Public School (now Wagga Wagga Public School), where he played Australian football

Australian football, also called Australian rules football or Aussie rules, or more simply football or footy, is a contact sport played between two teams of 18 players on an Australian rules football playing field, oval field, often a modified ...

, and was a keen member of the Army Cadet unit. He transferred to Wagga Wagga Grammar when he was 13, and was head cadet of its unit for two years.

Blamey began his working life in 1899 as a trainee school teacher at Lake Albert School. He transferred to South Wagga Public School in 1901, and in 1903 moved to Western Australia, where he taught for three years at Fremantle Boys' School. He coached the rifle shooting team of its cadet unit there to a win in the Western Australian Cup. He was raised in the Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

faith and remained involved with his church. By early 1906 he was a lay preacher, and church leaders in Western Australia offered him an appointment as an associate minister in Carnarvon, Western Australia

Carnarvon ( ) is a coastal town situated approximately north of Perth, in Western Australia. It lies at the mouth of the Gascoyne River on the Indian Ocean. The Shark Bay World Heritage Site, world heritage area lies to the south of the town an ...

.

Early military career

With the creation of the Cadet Instructional Staff of the Australian Military Forces, Blamey saw a new opportunity. He sat the exam and came third in Australia, but failed to secure an appointment as there were no vacancies in Western Australia. After correspondence with the military authorities he persuaded the Deputy Assistant Adjutant General, Major Julius Bruche, that he should be given the option of taking up an appointment for one of the vacancies in another state. He was appointed to a position in Victoria with the rank oflieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

, commencing duty in November 1906 with responsibility for school cadets in Victoria, and was confirmed in his rank and appointment the following 29 June.

In Melbourne, Blamey met Minnie Millard, the daughter of a Toorak stockbroker who was involved in the Methodist Church there. They were married at her home on 8 September 1909. His first child was born on 29 June 1910, and named Charles Middleton after a friend of Blamey's who had died in a shooting accident; but the boy was always called Dolf by his family. A second child, a boy named Thomas, was born four years later.

Blamey was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

on 1 December 1910, and became brigade major of the 12th Brigade Area. He then set his sights on attending staff college. There were two British staff colleges, at Camberley

Camberley is a town in north-west Surrey, England, around south-west of central London. It is in the Surrey Heath, Borough of Surrey Heath and is close to the county boundaries with Hampshire and Berkshire. Known originally as "Cambridge Tow ...

in England and Quetta

Quetta is the capital and largest city of the Pakistani province of Balochistan. It is the ninth largest city in Pakistan, with an estimated population of over 1.6 million in 2024. It is situated in the south-west of the country, lying in a ...

in India, and from 1908 one position was set aside for the Australian Army at each every year. No Australian officers managed to pass the demanding entrance examinations, but this requirement was waived to allow them to attend. In 1911, Blamey became the first Australian officer to pass the entrance examination. He commenced his studies at Quetta in 1912, and performed very well, completing the course in December 1913.

The usual practice was for Australian staff college graduates to follow their training with a posting to a British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

or British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

headquarters. He was initially attached to the 4th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps at Rawalpindi

Rawalpindi is the List of cities in Punjab, Pakistan by population, third-largest city in the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is a commercial and industrial hub, being the list of cities in P ...

, and then the staff of the Kohat Brigade on the North-West Frontier. Finally, he was assigned to the General Staff at Army Headquarters at Shimal. In May 1914, he was sent to Britain for more training, while his family returned home to Australia. He visited Turkey (including the Dardanelles), Belgium, and the battlefields of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

en route. In England he spent a brief time on attachment to the 4th Dragoon Guards at Tidworth before taking up duties on the staff of the Wessex Division, at that time entering its annual camp. On 1 July 1914, he was promoted to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

.

First World War

Following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Blamey was transferred to the

Following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Blamey was transferred to the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

, where he worked in the Intelligence Branch preparing daily summaries for the King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

and the Secretary of State for War

The secretary of state for war, commonly called the war secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The secretary of state for war headed the War Offic ...

, Lord Kitchener. Fully trained staff officers were rare and valuable in the Australian Army, and while still in Britain, Blamey was appointed to the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) as general staff officer, Grade 3 (Intelligence), on the staff of Major General William Bridges's 1st Division. As such, he reported to the 1st Division's GSO1, Lieutenant Colonel Brudenell White. In November 1914 he sailed for Egypt with Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Harry Chauvel, to join the Australian contingent there. His appointment as GSO 3 was confirmed with effect from 10 December.

Gallipoli

Along with Bridges, White, and other members of 1st Division headquarters, Blamey left the battleship in a trawler and landed on the beach at Anzac Cove at 07:20 on 25 April 1915. He was sent to evaluate the need for reinforcements by Colonel James McCay's 2nd Brigade on the 400 Plateau. He confirmed that they were needed, and the reinforcements were sent. On the night of 13 May 1915, Blamey, in his capacity as 1st Division intelligence officer, led a patrol consisting of himself,

On the night of 13 May 1915, Blamey, in his capacity as 1st Division intelligence officer, led a patrol consisting of himself, Sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

J. H. Will and Bombardier A. A. Orchard, behind the Turkish lines in an effort to locate the Olive Grove guns that had been harassing the beach. Near Pine Ridge, an enemy party of eight Turks approached; when one of them went to bayonet Orchard, Blamey shot the Turk with his revolver. In the action that followed, six Turks were killed. He withdrew his patrol back to the Australian lines without locating the guns. For this action, he was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

. Mentioned in Despatches.

Blamey was always interested in technical innovation, and was receptive to unorthodox ideas. He was instrumental in the adoption of the periscope rifle at Gallipoli, a device which he saw during an inspection of the front line. He arranged for the inventor, Lance Corporal

Lance corporal is a military rank, used by many English-speaking armed forces worldwide, and also by some police forces and other uniformed organisations. It is below the rank of corporal.

Etymology

The presumed origin of the rank of lance corp ...

W. C. B. Beech, to be seconded to division headquarters to develop the idea. Within a few days, the design was perfected and periscope rifles began to be used throughout the Australian trenches.

On 21 July 1915 Blamey was given a staff appointment as a general staff officer, Grade 2 (GSO2), Appointed General Staff Officer—2nd Grade. with the temporary rank of lieutenant-colonel. and with effect from 2 August joined the staff of the newly formed 2nd Division in Egypt as its assistant adjutant and quartermaster general (AA&QMG) – the senior administrative officer of the division. Its commander, Major General James Gordon Legge, preferred to have an Australian colonel in this post as he felt that a British officer might not take such good care of the troops. The 2nd Division Headquarters embarked for Gallipoli on 29 August 1915, but Blamey was forced to remain in Egypt as he had just had an operation for haemorrhoids. He finally returned to Anzac on 25 October 1915, remaining for the rest of the campaign.

Western Front

After the Australian forces moved to the Western Front in 1916, Blamey returned to the 1st Division as GSO1 on 10 July. Appointed GSO1. At the Battle of Pozières, he developed the plan of attack which captured the town, for which he received another mention in despatches, Mentioned in Despatches. and was awarded theDistinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

in the 1917 New Year Honours

The 1917 New Year Honours were appointments by King George V to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of the British Empire. The appointments were published in several editions of ''The London Gazette'' in Ja ...

. New Year's Honours 1917. DSO.

He was considered as a possible brigade commander, but he had never commanded a battalion, which was usually regarded as a prerequisite for brigade command. He was therefore appointed to command the 2nd Infantry Battalion on 3 December 1916. On 28 December, Blamey, as senior ranking battalion commander, took over as acting commander of the 1st Infantry Brigade. On 9 January 1917, he went on leave, handing over command to Lieutenant Colonel Iven Mackay. However, when General Headquarters (GHQ) BEF found out about this use of a staff college graduate, it reminded I ANZAC Corps that "it is inadvisable to release such officers for command of battalions unless they have proved to be unequal to their duties on staff".

Blamey therefore returned to 1st Division Headquarters. Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

Sir William Birdwood did, however, promote Blamey to full colonel, backdated to 1 December 1916, thereby making him technically senior to a number of recently promoted brigadier generals, that rank being only held temporarily. His division commander, Major General H. B. Walker, had Blamey mentioned in despatches for this period of battalion and brigade command, Mentioned in Despatches. Mentioned in Despatches. although the battalion had spent most of the time out of the line and there had been no significant engagements. Blamey was also acting commander of the 2nd Brigade during a rest period from 27 August to 4 September 1917.

On 8 September he was hospitalised with vomiting and coughing. He was sent to England where he was admitted to the 3rd London General Hospital for treatment for debilitating psoriasis

Psoriasis is a long-lasting, noncontagious autoimmune disease characterized by patches of abnormal skin. These areas are red, pink, or purple, dry, itchy, and scaly. Psoriasis varies in severity from small localized patches to complete b ...

on 22 September, and did not return to duty until 8 November 1917, by which time he had been promoted to brevet lieutenant-colonel on 24 September. He was made a Companion of St Michael and St George in the 1918 New Year's list, Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG). and received another mention in despatches in May 1918. Mentioned in Despatches.

On 1 June 1918, Lieutenant General John Monash

General (Australia), General Sir John Monash (; 27 June 1865 – 8 October 1931) was an Australian civil engineer and military commander of the World War I, First World War. He commanded the 13th Brigade (Australia), 13th Infantry Brigade befor ...

succeeded Birdwood as commander of the Australian Corps, and Blamey was promoted to the rank of brigadier general to replace White as the corps Brigadier General General Staff (BGGS). He played a significant role in the success of the Australian Corps in the final months of the war. He remained interested in technological innovation. He was impressed by the capabilities of the new models of tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

s and pressed for their use in the Battle of Hamel, where they played an important part in the success of the battle. Monash acknowledged Blamey's role in the Australian Corps' success in the Battle of Amiens in August and the Battle of the Hindenburg Line in September.

The Major General General Staff (MGGS) of the British Fourth Army, of which the Australian Corps was a part during these battles, Major General Archibald Montgomery-Massingberd, was a former instructor of Blamey's at Quetta. He declared himself "full of admiration for the staff work of the Australian Corps." Monash later wrote:

Blamey's loyalty to Monash would continue after the latter's death in 1931. For his services as Corps Chief of Staff, Blamey was appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1919, Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB). mentioned in despatches twice more, Mentioned in Despatches. Mentioned in Despatches. and was awarded the French . Croix de Guerre.

Inter-war years

General staff

Blamey arrived back in Australia on 20 October 1919 after an absence of seven years, and became director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters in Melbourne. His AIF appointment was terminated on 19 December 1919, and on 1 January 1920, he was simultaneously confirmed in the rank of lieutenant-colonel and promoted to substantive colonel, also receiving the honorary rank of brigadier-general with effect from 1 June 1918. In May 1920, he was appointed Deputy Chief of the General Staff. His first major task was the creation of theRoyal Australian Air Force

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is the principal Air force, aerial warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Army. Constitutionally the Governor-Gener ...

(RAAF). The government established a joint Army–Navy board to provide recommendations on the matter, with Blamey and Lieutenant Colonel Richard Williams as the Army representatives. Blamey supported the creation of a separate air force, albeit one still subordinate to the Army and Navy. He refused to yield, however, on his opposition to the Navy's demand that Lieutenant Colonel Stanley Goble become its first chief.

In November 1922 Blamey embarked for London to be the Australian representative on the Imperial General Staff. He reported that the "conception of an Imperial General Staff ... was absolutely dead". The British Army saw little use in the concept of a combined staff which could coordinate the defence of the British Empire. He became involved with the development of the Singapore strategy

The Singapore strategy was a naval defence policy of the United Kingdom that evolved in a series of Military operation plan, war plans from 1919 to 1941. It aimed to deter aggression by Japan by providing a base for a fleet of the Royal Navy in ...

, and he briefed Prime Minister Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was an Australian politician, statesman and businessman who served as the eighth prime minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929. He held office as ...

on it for the 1923 Imperial Conference

The 1923 Imperial Conference met in London in the autumn of 1923, the first attended by the new Irish Free State. While named the Imperial Economic Conference, the principal activity concerned the rights of the Dominions in regards to determinin ...

, at which it was formally adopted. Even in 1923, though, Blamey was sceptical about the strategy.

When White retired as Chief of General Staff in 1923, Blamey was widely expected to succeed him, as he had as chief of staff of the Australian Corps in France, but there were objections from more senior officers, particularly Major General Victor Sellheim, at being passed over. Instead, the Inspector General, Lieutenant General Sir Harry Chauvel, was made Chief of General Staff as well, while Blamey was given the new post of Second CGS, in which he performed most of the duties of Chief of General Staff.

Seeing no immediate prospects for advancement, Blamey transferred from the Permanent Military Forces to the Militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

on 1 September 1925. For the next 14 years he would remain in the Army as a part-time soldier. On 1 May 1926 he assumed command of the 10th Infantry Brigade, part of the 3rd Division. Blamey stepped up to command the 3rd Division on 23 March 1931, and was promoted to major general, one of only four Militia officers promoted to this rank between 1929 and 1939. In 1937 he was transferred to the unattached list.

Chief Commissioner of the Victoria Police

In 1923, the

In 1923, the Victoria Police

Victoria Police is the primary law enforcement agency of the Australian States and territories of Australia, state of Victoria (Australia), Victoria. It was formed in 1853 and currently operates under the ''Victoria Police Act 2013''.

, Victor ...

went on strike, and Monash and McCay established a Special Constabulary Force to carry out police duties. After the Chief Commissioner, Alexander Nicholson, resigned for ill-health in 1925, Chauvel recommended Blamey for the post. He became Chief Commissioner on 1 September 1925 for a five-year term, with a salary of £A1,500 per annum, equivalent to in .

Blamey set about addressing the grievances that had caused the strike, which he felt "were just, even if they went the wrong way about them". Blamey improved pay and conditions, and implemented the recommendations of the Royal Commission into the strike. He attempted to introduce faster promotion based on merit, but this was unpopular with the Police Association, and was abandoned by his successors.

As in the Army, he showed a willingness to adopt new ideas. He introduced police dogs, and increased the number of police cars equipped with two-way radios from one in 1925 to five in 1930. He also boosted the numbers of policewomen on the force.

Blamey became involved in his first and greatest scandal soon after taking office. During a raid on a brothel in Fitzroy on 21 October 1925, the police encountered a man who produced Blamey's police badge, No. 80. Blamey later said that he had given his key ring, which included his badge, to a friend who had served with him in France, so that the man could help himself to some alcohol in Blamey's locker at the Naval and Military Club. His story was corroborated by his friend Stanley Savige

Lieutenant general (Australia), Lieutenant General Sir Stanley George Savige, (26 June 1890 – 15 May 1954) was an Australian Army soldier and officer who served in the First World War and Second World War.

In March 1915, after the outbr ...

, who was with him at the time. Blamey protected the man in question, who he said was married with children, and refused to identify him. The man has never been identified, but the description given by the detectives and the brothel owner did not match Blamey.

During the 1920s, Victoria had repressive and restrictive drinking laws, including the notorious six o'clock closing. Blamey took the position that it was the job of the police to enforce the laws, even if they did not support them. Many members of the public did not agree with this attitude, maintaining that the police should not uphold such laws. Almost as controversially, Blamey drew a sharp distinction between his personal life and his job. His presence in a hotel after closing time was always welcome, as it meant that drinking could continue, for it was known that it would not be raided while he was there; but other citizens felt that it was unjust when they were arrested for breaking the same laws.

As Police Commissioner Blamey defended the actions of the police during the 1928 Waterside Workers' Federation dispute, during which police opened fire, killing a striking worker who was also a Gallipoli veteran, and wounding several others. His treatment of the unionists was typical of his hard line anti-communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

beliefs and as such his relations with left-wing governments were tense.

Blamey was re-appointed as Chief Commissioner in 1930 but at a reduced salary of £A1,250 per annum, equivalent to in . A year later it was reduced still further, to £A785, equivalent to in , due to cutbacks as a result of the

Blamey was re-appointed as Chief Commissioner in 1930 but at a reduced salary of £A1,250 per annum, equivalent to in . A year later it was reduced still further, to £A785, equivalent to in , due to cutbacks as a result of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

. His wife Minnie became an invalid, and by 1930 no longer accompanied him in public. His son Dolf, now an RAAF

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is the principal aerial warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Army. Constitutionally the governor-general of Aus ...

flying officer, was killed in an air crash at RAAF Base Richmond in October 1932, and Minnie died in October 1935. Blamey was knighted in the 1935 New Year Honours, Knight Bachelor.Citation: "Major General Thomas Albert Blamey, C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O. Chief Commissioner of Police, State of Victoria. For services in connection with the Centenary Celebrations." Noted that Blamey has received his knighthood by

Letters Patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

. and in 1936 he was appointed a Commander of the Venerable Order of Saint John. Commander of The Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem.

A second scandal occurred in 1936 when Blamey attempted to cover up details of the shooting of the superintendent of the Criminal Investigation Branch, John O'Connell Brophy, whom Blamey had appointed to the post. The story put about was that Brophy had taken two women friends and a chauffeur along with him to a meeting with a police informant. While they were waiting for the informant, they had been approached by armed bandits, and Brophy had opened fire and had himself been wounded. In order to cover up the identities of the two women involved, Blamey initially issued a press release to the effect that Brophy had accidentally shot himself (three times). The Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of govern ...

, Albert Dunstan, gave Blamey the choice of resigning or being dismissed. The latter meant the loss of pension rights and any future prospects of employment in the Public Service or the Army. He reluctantly submitted his resignation on 9 July 1936.

Other activities and marriage

From March 1938 Blamey supplemented his income by making weekly broadcasts on international affairs on Melbourne radio station 3UZ under the pseudonym "the Sentinel". Like the station's general manager, Alfred Kemsley, Blamey felt that Australians were poorly informed about international affairs, and set about raising awareness of matters that he believed would soon impact them greatly. He was appalled atNazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's persecution of Jews

The persecution of Jews has been a major event in Jewish history prompting shifting waves of refugees and the formation of diaspora communities. As early as 605 BC, Jews who lived in the Neo-Babylonian Empire were persecuted and deported. Antis ...

, and saw a clear and growing menace to world peace from both Germany and the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

. His 15-minute weekly talks continued until the end of September 1939, by which time the war that he had warned was coming had started.

On 5 April 1939 he married Olga Ora Farnsworth, a 35-year-old fashion artist, at St John's Anglican Church, Toorak.

League of National Security

Blamey was leader of the clandestine far-right League of National Security, also known as the "White Army", described as afascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

paramilitary group. The group, which existed for about eight years from 1931, comprised several senior army officers, including Colonel Francis Derham, a Melbourne lawyer, and Lieutenant Colonel Edmund Herring, later Chief Justice of Victoria.

Some members had been members of the New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

-based New Guard, and both groups were involved in street fights with leftist groups. This was reportedly a response to the rise of communism in Australia. Its members stood ready to take up arms to stop a Catholic or communist revolution.Manpower Committee and militia recruiting

In November 1938, Blamey was appointed chairman of the Commonwealth Government's Manpower Committee and Controller General of Recruiting. As such, he laid the foundation for the expansion of the Army in the event of war with Germany or Japan, which he now regarded as inevitable. He headed a successful recruiting campaign which doubled the size of the part-time volunteer Militia from 35,000 in September 1938 to 70,000 in March 1939. Henry Somer Gullett and Richard Casey, who had served with Blamey at Gallipoli and in France, put Blamey's name forward toPrime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Australia, from 1932 until his death in 1939. He held office as the inaugural leader of the United Australia Par ...

as a possible commander in chief in the event of a major war. "We've got some brilliant staff officers", Casey told Lyons, "but Blamey is a commander. That's the difference."

Lyons initially had concerns about Blamey's morals, but Casey and Lyons summoned Blamey to a meeting in Canberra, after which Lyons designated him for the job. Lyons died on 7 April 1939, and was replaced as prime minister by Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

, another prominent supporter of Blamey's. Two other officers, Major Generals Gordon Bennett and John Lavarack, were considered, and also had strong and well-connected supporters, but unlike Blamey they were public critics of the government's defence policies.

Second World War

Middle East

On 13 October 1939, a month after the outbreak of the Second World War, Blamey was promoted to lieutenant general, and appointed to command the 6th Division, the first formation of the new Second Australian Imperial Force, and received the AIF service number VX1. Menzies limited his choice of commanders by insisting that they be selected from the Militia rather than the Permanent Military Forces (PMF), the Army's full-time, regular component. For brigade commanders he chose

On 13 October 1939, a month after the outbreak of the Second World War, Blamey was promoted to lieutenant general, and appointed to command the 6th Division, the first formation of the new Second Australian Imperial Force, and received the AIF service number VX1. Menzies limited his choice of commanders by insisting that they be selected from the Militia rather than the Permanent Military Forces (PMF), the Army's full-time, regular component. For brigade commanders he chose Brigadier

Brigadier ( ) is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore (rank), commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several t ...

s Arthur Allen, Leslie Morshead and Stanley Savige. He selected Brigadier Edmund Herring to command the 6th Division artillery, Colonel Samuel Burston for its medical services, and Lieutenant Colonels Clive Steele and Jack Stevens for its engineers and signals. All except Allen had previously served with him during his time commanding the 3rd Division in Melbourne. For his two most senior staff officers, he chose two PMF officers, Colonel Sydney Rowell as GSO1 and Lieutenant Colonel George Alan Vasey as AA&QMG.

In February 1940, the War Cabinet decided to form a second AIF division, the 7th Division, and group the 6th and 7th Divisions together as I Corps, with Blamey as its commander. On Blamey's recommendation, Major General Iven Mackay was appointed to succeed him in command of the 6th Division, while Lieutenant General John Lavarack, a PMF officer, assumed command of the 7th Division. Blamey took Rowell with him as his corps chief of staff, and picked Major General Henry Wynter as his administrative officer. Blamey flew to Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

on a Qantas

Qantas ( ), formally Qantas Airways Limited, is the flag carrier of Australia, and the largest airline by fleet size, international flights, and international destinations in Australia and List of largest airlines in Oceania, Oceania. A foundi ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

in June 1940. He refused to allow his troops to perform police duties in Palestine, and established warm relations with the Jewish community there, becoming a frequent guest in their homes.

As commander of the AIF, Blamey was answerable directly to the Minister of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divid ...

, rather than to the Military Board, with a charter based on that given to Bridges in 1914. Part of this required that his forces remain together as cohesive units, and that no Australian forces were to be deployed or engaged without the prior consent of the Australian government. Blamey was not inflexible, and permitted Australian units to be detached when there was a genuine military need. Because the situation in the Middle East lurched from crisis to crisis, this resulted in his troops becoming widely scattered at times. When the crises had passed, however, he wanted units returned to their parent formations. This resulted in conflicts with British commanders. The first occurred in August 1940 when the British Commander in Chief Middle East Command, General Sir Archibald Wavell

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, (5 May 1883 – 24 May 1950) was a senior officer of the British Army. He served in the Second Boer War, the Bazar Valley Campaign and the First World War, during which he was wounded ...

, and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, ordered the 16th Infantry Brigade to move to Egypt. Blamey refused on the grounds that the brigade was not yet fully equipped, but eventually compromised, sending it on the understanding that it would soon be joined by the rest of the 6th Division.

I Corps assumed responsibility for the front in

I Corps assumed responsibility for the front in Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika (, , after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between the 16th and 25th meridians east, including the Kufra District. The coastal region, als ...

on 15 February 1941, but within days Blamey was informed that his troops would be sent on the expedition to Greece. Blamey has been criticised for allowing this when he knew it was extremely hazardous, after he was told that Menzies had approved. He insisted, however, on sending the veteran 6th Division first instead of the 7th Division, resulting in a heated argument with Wavell, which Blamey won. He was under no illusions about the odds of success, and immediately prepared plans for an evacuation. His foresight and determination saved many of his men, but he lost credibility when he chose his son Tom to fill the one remaining seat on the aircraft carrying him out of Greece. The campaign exposed deficiencies in the Australian Army's training, leadership and staff work that had passed unnoticed or had not been addressed in the Libyan Campaign. The pressure of the campaign opened a rift between Blamey and Rowell, which was to have important consequences. While Rowell and Brigadier William Bridgeford were extremely critical of Blamey's performance in Greece, this opinion was not widely held. Wavell reported that "Blamey has shown himself a fine fighting commander in these operations and fitted for high command."

The political fallout from the disastrous Battle of Greece led to Blamey's appointment as Deputy Commander in Chief Middle East Command in April 1941. Appointed Deputy Commander in Chief, Middle East. However, to ensure that command would not pass to Blamey in the event of something happening to Wavell, the British government promoted Sir Henry Maitland Wilson to general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in June. Soon afterwards, Wavell was replaced by General Sir Claude Auchinleck

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck ( ) (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Indian Army commander who saw active service during the world wars. A career soldier who spent much of his militar ...

. Blamey was subsequently promoted to the same rank on 24 September 1941, becoming only the fourth Australian to reach this rank, after Monash, Chauvel and White. During the Syrian campaign against the Vichy French, Blamey took decisive action to resolve the command difficulties caused by Wilson's attempt to direct the fighting from the King David Hotel in Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

by interposing Lavarack's I Corps headquarters.

During Blamey's absence in Greece, AIF units had become widely scattered, with forces being deployed to Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, and the 9th Division and the 18th Infantry Brigade coming under siege in Tobruk. Blamey would spend the rest of the year attempting to reassemble his forces. This led to a clash with Auchinleck over the relief of Tobruk, where Blamey accepted Burston's advice that the Australian troops there should be relieved on medical grounds. Menzies, and later his successors, Arthur Fadden and John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), having been most ...

, backed Blamey, and Auchinleck and Churchill were forced to give way resulting in the relief of most of the Australian troops by the British 70th Division. For his campaigns in the Middle East, Blamey was created a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

on 1 January 1942. Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. He was Mentioned in Despatches for the eighth time, and was awarded the Greek War Cross, First Class.

Papuan campaign

The defence of Australia took on a new urgency in December 1941 with the entry of Japan into the war. Within the Army there was a concern that Bennett or Lavarack would be appointed as commander-in-chief. In March 1942, Vasey, Herring and Steele approached the Minister for the Army, Frank Forde, with a proposal that all officers over the age of 50 be immediately retired and Major General Horace Robertson be appointed commander-in-chief. This "revolt of the generals" collapsed with the welcome news that Blamey was returning from the Middle East to become commander-in-chief of Australian Military Forces.General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

arrived in Australia in March 1942 to become Supreme Commander South West Pacific Area (SWPA). In addition to his duties as commander-in-chief, Blamey became commander of Allied Land Forces, South West Pacific Area. In the reorganisation that followed his return to Australia on 23 March, Blamey appointed Lavarack to command the First Army, Mackay to command the Second Army, and Bennett to command the III Corps in Western Australia. Vasey became deputy chief of the general staff (DCGS), while Herring took over Northern Territory Force, and Robertson became commander of the 1st Armoured Division. Blamey's Allied Land Forces Headquarters (LHQ) was established in Melbourne, but after MacArthur's General Headquarters (GHQ) moved to Brisbane in July 1942, Blamey established an Advanced LHQ in nearby St Lucia, Queensland.

The Allied command structure was soon put under strain by Australian reverses in the Kokoda Track campaign. MacArthur was highly critical of the Australian performance, and confided to the

The Allied command structure was soon put under strain by Australian reverses in the Kokoda Track campaign. MacArthur was highly critical of the Australian performance, and confided to the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and a ...

, General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

, that "the Australians have proven themselves unable to match the enemy in jungle fighting. Aggressive leadership is lacking." MacArthur told Curtin that Blamey should be sent up to New Guinea to take personal command of the situation. Curtin later confessed that "in my ignorance (of military matters) I thought that the Commander in Chief should be in New Guinea." Jack Beasley suggested that Blamey would make a convenient scapegoat: " Moresby is going to fall. Send Blamey up there and let him fall with it!"

Blamey felt he had no choice, but his assumption of command of New Guinea Force sat uneasily with Rowell, the commander of I Corps there, who saw it as displaying a lack of confidence in him. A petulant Rowell would not be mollified, and, after a series of disagreements, Blamey relieved Rowell of his command, replacing him with Herring. More reliefs followed. Herring relieved Brigadier Arnold Potts of the 21st Infantry Brigade, replacing him with Brigadier Ivan Dougherty on 22 October. Five days later, Blamey replaced Allen as the 7th Division's commander with Vasey. Nor were generals the only ones to be removed. Blamey cancelled Chester Wilmot's accreditation as a war correspondent

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories first-hand from a war, war zone.

War correspondence stands as one of journalism's most important and impactful forms. War correspondents operate in the most conflict-ridden parts of the wor ...

in October 1942 for spreading a false rumour that Blamey was taking payments from the laundry contractor at Puckapunyal. Wilmot was reinstated, but on 1 November 1942, Blamey again terminated Wilmot's accreditation, this time for good.

Blamey made a controversial speech to the 21st Infantry Brigade on 9 November 1942. According to the official historian, Dudley McCarthy:

The implication of cowardice was seen as contrasting with his own inability to stand up to MacArthur and the Prime Minister. Rowell felt that Blamey "had not shown the necessary 'moral courage' to fight the Cabinet on an issue of confidence in me." When American troops suffered serious reverses in the Battle of Buna–Gona, Blamey turned the tables on MacArthur. According to Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

George Kenney, the commander of Allied Air Forces, Blamey "frankly said he would rather send in more Australians, as he knew they would fight ... a bitter pill for MacArthur to swallow". In January 1943, he visited the Buna–Gona battlefield, surprising Vasey at how far forward he went, seemingly unconcerned about his safety. Blamey was impressed by the strength of the Japanese fortifications that had been captured, later telling correspondents that Australian and American troops had performed miracles.

At the Battle of Wau in January 1943, Blamey won the battle by acting decisively on intelligence, shifting the 17th Infantry Brigade from Milne Bay

Milne Bay is a large bay in Milne Bay Province, south-eastern Papua New Guinea. More than long and over wide, Milne Bay is a sheltered deep-water harbor accessible via Ward Hunt Strait. It is surrounded by the heavily wooded Stirling Range (Papu ...

in time to defeat the Japanese attack. The official historian, Dudley McCarthy, later wrote:

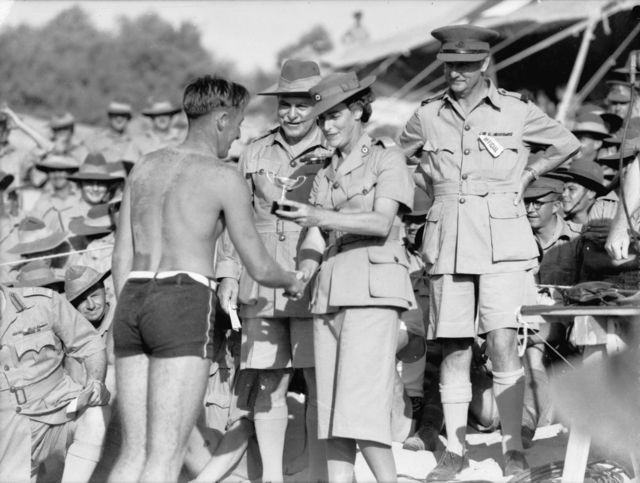

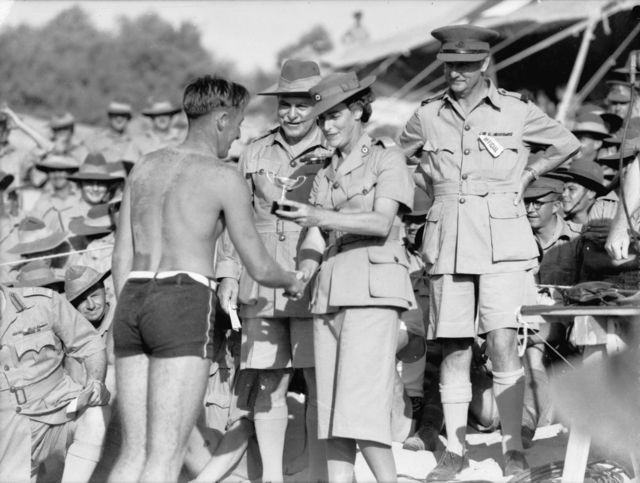

For the Papuan Campaign, MacArthur awarded Blamey the American Distinguished Service Cross, and Blamey was created a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire on 28 May 1943. Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire. This was unusual as it was the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

's policy not to award knighthoods, but was done as a response to the British government's awards to British and American officers for the North African campaign

The North African campaign of World War II took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943, fought between the Allies and the Axis Powers. It included campaigns in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts (Western Desert campaign, Desert Wa ...

. Blamey's and Herring's knighthoods would be the last that the Labor government would award to Australian soldiers.

New Guinea Campaign

The relationship between MacArthur and Blamey was generally good, and they had great respect for each other's abilities. MacArthur's main objection was that as commander-in-chief of AMF as well as commander of Allied Land Forces, Blamey was not wholly under his command. Official historian Gavin Long argued that: The next operation was MacArthur's

The next operation was MacArthur's Operation Cartwheel

Operation Cartwheel (1943 – 1944) was a major military operation undertaken by the Allies in the Pacific theatre of World War II. The ultimate goal of Cartwheel was to neutralize the major Japanese base at Rabaul. The operation was di ...

, an advance on the major Japanese base at Rabaul. The Australian Army was tasked with the capture of the Huon Peninsula

Huon Peninsula is a large rugged peninsula on the island of New Guinea in Morobe Province, eastern Papua New Guinea. It is named after French explorer Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec. The peninsula is dominated by the steep Saruwaged and Finist ...

. Blamey was ordered to again assume personal command of New Guinea Force. His concept, which he developed with Herring and Frank Berryman, who had replaced Vasey as DCGS, was to draw the Japanese forces away from Lae with a demonstration against Salamaua

Salamaua () was a small town situated on the northeastern coastline of Papua New Guinea, in Salamaua Rural LLG, Morobe province. The settlement was built on a minor isthmus between the coast with mountains on the inland side and a headland. The c ...

, and then capture Lae with a double envelopment. Blamey remained a devotee of new technology. His plan called for the use of the landing craft of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, and he intended to cross the Markham River

The Markham River is a river in eastern Papua New Guinea. It originates in the Finisterre Range and flows for to empty into the Huon Gulf at Lae.

Course

The Markham is a major river in eastern Papua New Guinea. Its headwaters (''Umi'' and ''Bi ...

with the aid of paratroops. Supplies would be brought across the river using DUKWs, a relatively new invention. He also attempted to acquire helicopters, but met resistance from the RAAF, and they were never delivered. MacArthur accepted a number of changes that Blamey made to his strategy, probably the most notable of which was putting the landing on New Britain before Blamey's attack on Madang.

The campaign started well; Lae was captured well ahead of schedule. Blamey then handed over command of New Guinea Force to Mackay and returned to Australia. The 7th Division then advanced through the Ramu Valley while the 9th Division landed at Finschhafen. The campaign then slowed owing to a combination of logistical difficulties and Japanese resistance. Blamey responded to a request from Mackay to relieve Herring, whose chief of staff had been killed in an aircraft accident. He immediately sent Morshead. In February 1944 there was criticism in Parliament of the way that Blamey had "side tracked" various generals; the names of Bennett, Rowell, Mackay, Wynter, Herring, Lavarack, Robertson, Morshead and Clowes were mentioned. Blamey responded,

Frank Forde criticised Blamey for having too many generals. Blamey could only reply that the Australian Army had one general for 15,741 men and women compared to one per 9,090 in the British Army.

Blamey was annoyed by the media campaign run against him by William Dunstan and Keith Murdoch of ''

Frank Forde criticised Blamey for having too many generals. Blamey could only reply that the Australian Army had one general for 15,741 men and women compared to one per 9,090 in the British Army.

Blamey was annoyed by the media campaign run against him by William Dunstan and Keith Murdoch of ''The Herald and Weekly Times

''The Herald and Weekly Times'' Pty Ltd (HWT) is a newspaper publishing company based in Melbourne, Australia. It is owned and operated by News Pty Ltd, which as News Ltd, purchased the HWT in 1987.

Newspapers

The HWT's newspaper interests dat ...

'' newspaper group, but success in New Guinea led to a change of heart at the newspaper, and Blamey even accepted a dinner invitation from Murdoch in 1944. There was another victory, though, far more significant. The Army had taken heavy casualties from malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

in the fighting in 1942. Blamey took the advice of Edward Ford and Neil Hamilton Fairley, and strongly backed their ultimately successful efforts to control the disease. To acquaint himself with the issues, Blamey read through ''Manson's Tropical Diseases'', the standard medical textbook on the subject. He promoted the work of Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey, (; 24 September 1898 – 21 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his ro ...

on the development of penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

, and wrote to Curtin urging that £A200,000, equivalent to in , be earmarked for Florey's vision of a national institute for medical research in Canberra, which ultimately became the John Curtin School of Medical Research.

Blamey was involved in discussions with the government over the size of the Army to be maintained. Now that the danger of invasion of Australia had passed, the government reconsidered how the nation's resources, particularly of manpower, should be distributed. Blamey pressed for a commitment to maintain three AIF divisions, as only they could legally be sent north of the equator where the final campaigns would be fought. He urged that the Empire Air Training Scheme

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), often referred to as simply "The Plan", was a large-scale multinational military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand during the Second Wo ...

be curtailed, and opposed MacArthur's proposal to use the Australian Army primarily for logistic support and leave combat roles principally to American troops.

Final campaigns

On 5 April 1944, Blamey departed for San Francisco on board for the first leg of a voyage to attend the 1944

On 5 April 1944, Blamey departed for San Francisco on board for the first leg of a voyage to attend the 1944 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference

Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences were biennial meetings of Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom and the Dominion members of the British Commonwealth of Nations. Seventeen Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences were held betwe ...

in London as part of Curtin's party. The journey was made by sea and rail due to Curtin's fear of flying. Also on board the ship were American military personnel returning to the United States, and some 40 Australian war brides. Blamey "was always attractive to women and attracted by them. Advancing years had not reduced either his taste for amorous adventures or his capacity to enjoy them", and he brought with him several cases of spirits. The rowdy goings-on in Blamey's cabin did not endear him to the Prime Minister, who was a reformed alcoholic. The party travelled by train to Washington, D.C., where Blamey was warmly greeted by the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

, and briefed the Combined Chiefs of Staff on the progress of the war in SWPA. In London Blamey had a series of meetings with the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, and was briefed on Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The ope ...

by General Sir Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

and Air Chief Marshal

Air chief marshal (Air Chf Mshl or ACM) is a high-ranking air officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many Commonwealth of Nations, countries that have historical British i ...

Sir Arthur Tedder. Blamey was disappointed to have to turn down an offer to accompany the invasion as a guest of General Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

because Curtin feared that the invasion would lead to retaliatory German bombing, and wanted to be far away before it started.

As a matter of policy, Curtin wanted Australian forces to be involved in liberating New Guinea. MacArthur therefore proposed that Australian troops relieve the American garrisons on New Britain

New Britain () is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi Island, Umboi the Dampie ...

, Bougainville and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

. However, MacArthur balked at Blamey's proposal to replace the seven American divisions with just seven Australian brigades, resulting in the 6th Division being employed as well. The larger garrisons permitted offensive operations, and demanded them if the 6th Division was to be freed for employment elsewhere. These operations aroused considerable criticism on the grounds that they were unnecessary, that the troops should have been employed elsewhere, and that the Army's equipment and logistics were inadequate. Blamey vigorously defended his aggressive policy to reduce the bypassed Japanese garrisons and free the civilian population, but some felt that he went too far in putting his case publicly in a national radio broadcast. He was also criticised for not spending enough time in forward areas, although he spent more than half his time outside Australia in 1944, and between April 1944 and April 1945 travelled by air, by sea and by land. Blamey urged that the 7th Division not be sent to Balikpapan, an operation that he regarded as unnecessary. On this occasion, he was not supported by the government, and the operation went ahead as planned.

Gavin Long wrote:

On 2 September 1945, Blamey was with MacArthur on and signed the Japanese surrender document on behalf of Australia. He then flew to Morotai and personally accepted the surrender of the remaining Japanese in the South West Pacific. He insisted that Australia should be represented in the Allied occupation of Japan.

After the Second World War

MacArthur abolished SWPA on 2 September 1945, and on 15 September Blamey offered to resign. The war was over, and the post of commander-in-chief was now a purely administrative one. His offer was not accepted, but on 14 November, the government abruptly announced that it had accepted his resignation, effective 30 November. A farewell party was held in Melbourne, which was attended by 66 brigadiers and generals. Blamey was given time to write up his despatches, and was formally retired on 31 January 1946. Forde asked Blamey if he wanted anything in way of recognition for his services, and Blamey asked for knighthoods for his generals, but Forde could not arrange this. In the end, Forde decided to give Blamey the Buick staff car he had used during the war, which had clocked up in the Middle East and the South West Pacific. Blamey returned to Melbourne, where he devoted himself to business affairs, to writing, and to promoting the welfare of ex-service personnel. In September 1948, Blamey paid a visit to Japan, where he was warmly greeted on arrival atIwakuni

file:20100724 Iwakuni 5235.jpg, 270px, Kintai Bridge

file:Iwakuni city center area Aerial photograph.2008.jpg, 270px, Iwakuni city center

is a Cities of Japan, city located in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of ...

by Horace Robertson, the commander of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, who also provided an RAAF honour guard. MacArthur sent his own aircraft, the ''Bataan'', to collect Blamey and bring him to Tokyo, where he met Blamey at the airport and gave him another warm greeting. In the late 1940s Blamey became involved with The Association, an organisation similar to the earlier League of National Security, which was established to counter a possible communist coup. He was the head of the organisation until ill health forced him to stand down in favour of Morshead in 1950.

Promotion to field marshal

Menzies became prime minister again in December 1949, and he resolved that Blamey should be promoted to the rank of field marshal, something that had been mooted in 1945. The recommendation went via the

Menzies became prime minister again in December 1949, and he resolved that Blamey should be promoted to the rank of field marshal, something that had been mooted in 1945. The recommendation went via the Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

, William McKell, to Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

in London, which appeared to reply that a dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

officer could not be promoted to the rank. Menzies pointed out that Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...