Theodore Stevens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theodore Fulton Stevens Sr. (November 18, 1923 – August 9, 2010) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a

Stevens was born November 18, 1923, in Indianapolis, Indiana, the third of four children,Theodore Fulton "Ted" Stevens genealogy.

Stevens was born November 18, 1923, in Indianapolis, Indiana, the third of four children,Theodore Fulton "Ted" Stevens genealogy.

Rootsweb.com. Retrieved on May 31, 2007. in a small cottage built by his paternal grandfather after the marriage of his parents, Gertrude S. (née Chancellor) and George A. Stevens. The family later lived in Chicago, where George Stevens was an accountant before losing his job during the Great Depression.Mitchell, Donald Craig. (2001). ''Take My Land, Take My Life: The Story of Congress's Historic Settlement of Alaska Native Land Claims, 1960–1971''. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, p. 220. Around this time, when Ted Stevens was six years old, his parents divorced, and Stevens and his three siblings went back to Indianapolis to reside with their paternal grandparents, followed shortly thereafter by their father, who developed problems with his eyes and went blind for several years. Stevens's mother moved to California and sent for Stevens's siblings as she could afford to, but Stevens stayed in Indianapolis helping to care for his father and a mentally disabled cousin, Patricia Acker, who also lived with the family. The only adult in the household with a job was Stevens's grandfather. Stevens helped to support the family by working as a newsboy, and would later remember selling many newspapers on March 1, 1932, when newspaper headlines blared the news of the Lindbergh kidnapping. In 1934 Stevens's grandfather punctured a lung in a fall down a tall flight of stairs, contracted

In 1934 Stevens's grandfather punctured a lung in a fall down a tall flight of stairs, contracted

After graduating from high school in 1942, Stevens enrolled at

After graduating from high school in 1942, Stevens enrolled at

Stevens served in the

Stevens served in the

"The road north: Needing work, Stevens borrows $600, answers call to Alaska."

''Anchorage Daily News''. Retrieved June 1, 2007. Twenty years earlier Ely had been executive assistant to Secretary of the Interior

"Doctor Ray Lyman Wilbur: Third President of Stanford & Secretary of the Interior."

Paper presented at the Fortnightly Club of Redlands, California, meeting #1530. Retrieved on June 5, 2007. and by 1950 headed a prominent law firm specializing in

"Emil Usibelli (1893–1964)."

Retrieved on 2007-06-05. was trying to sell coal to the military, and Stevens was assigned to handle his legal affairs.

Stevens and Ann had three sons (Ben A. Stevens Sr., Walter, and Ted) and two daughters (Susan Covich and Elizabeth "Beth" Harper Stevens). Democratic Governor Tony Knowles appointed Ben to the

Stevens and Ann had three sons (Ben A. Stevens Sr., Walter, and Ted) and two daughters (Susan Covich and Elizabeth "Beth" Harper Stevens). Democratic Governor Tony Knowles appointed Ben to the

U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S ...

from 1968 to 2009. He was the longest-serving Republican Senator in history at the time he left office, though his record was later surpassed in January 2017 by Utah Senator Orrin Hatch

Orrin Grant Hatch (March 22, 1934 – April 23, 2022) was an American attorney and politician who served as a United States senator from Utah from 1977 to 2019. Hatch's 42-year Senate tenure made him the longest-serving Republican U.S. sena ...

. He was the president pro tempore of the United States Senate

The president pro tempore of the United States Senate (often shortened to president pro tem) is the second-highest-ranking official of the United States Senate, after the vice president. According to Article One, Section Three of the United ...

in the 108th and 109th Congresses from January 3, 2003, to January 3, 2007, and was the third U.S. Senator to hold the title of president pro tempore emeritus. He was previously Solicitor of the Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the m ...

from September 1960 to January 1961.

Stevens served for six decades in the American public sector

The public sector, also called the state sector, is the part of the economy composed of both public services and public enterprises. Public sectors include the public goods and governmental services such as the military, law enforcement, in ...

, beginning with his service as a pilot in World WarII. In 1952, his law career took him to Fairbanks, Alaska

Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the po ...

, where he was appointed U.S. Attorney the following year by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1956, he returned to Washington, D. C., to work in the Eisenhower Interior Department, eventually rising to become Senior Counsel and Solicitor of the Department of the Interior, where he played an important role as an executive official in bringing about and lobbying for statehood for Alaska.

After winning the Republican nomination, Stevens challenged Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

incumbent Ernest Gruening

Ernest Henry Gruening ( ; February 6, 1887 – June 26, 1974) was an American journalist and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, Gruening was the governor of the Alaska Territory from 1939 until 1953, and a United States Senator from Al ...

in the 1962 Senate election, though he was defeated. Afterwards, he was elected to the Alaska House of Representatives

The Alaska State House of Representatives is the lower house in the Alaska Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Alaska. The House is composed of 40 members, each of whom represents a district of approximately 17,756 people pe ...

in 1964 and became House majority leader in his second term. In 1968, Stevens ran unsuccessfully for the Republican nomination for U.S. Senate, losing to Elmer Rasmuson

Elmer Edwin Rasmuson (February 15, 1909 – December 1, 2000) was an American banker, philanthropist and politician in the territory and state of Alaska. He led the family business, National Bank of Alaska, for many decades as president and lat ...

, but was appointed to Alaska's other Senate seat when it became vacant later that year. As a Senator, Stevens played key roles in legislation that shaped Alaska's economic and social development, with Alaskans describing Stevens as "the state's largest industry". This legislation included the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 18, 1971, constituting at the time the largest land claims settlement in United States history. ANCSA was intended to resolve long-standin ...

, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) is a United States federal law signed by President Jimmy Carter on December 2, 1980. ANILCA provided varying degrees of special protection to over of land, including national parks, ...

, and the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. He was also known for his sponsorship of the Amateur Sports Act of 1978, which resulted in the establishment of the United States Olympic Committee

The United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee (USOPC) is the National Olympic Committee and the National Paralympic Committee for the United States. It was founded in 1895 as the United States Olympic Committee, and is headquartered in Col ...

.

In 2008

File:2008 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Lehman Brothers went bankrupt following the Subprime mortgage crisis; Cyclone Nargis killed more than 138,000 in Myanmar; A scene from the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing ...

, Stevens was embroiled in a federal corruption trial as he ran for re-election to the Senate. He was initially found guilty, and, eight days later, he was narrowly defeated by Anchorage Mayor Mark Begich. Stevens was the most senior U.S. Senator to have ever lost a reelection bid. However, before his sentencing, the indictment was dismissed – effectively vacating the conviction – when a Justice Department probe found evidence of gross prosecutorial misconduct

In jurisprudence, prosecutorial misconduct or prosecutorial overreach is "an illegal act or failing to act, on the part of a prosecutor, especially an attempt to sway the jury to wrongly convict a defendant or to impose a harsher than appropri ...

. Stevens died on August 9, 2010, near Dillingham, Alaska

Dillingham ( esu, Curyung; russian: Диллингхем ), also known as Curyung, is a city in Dillingham Census Area, Alaska, United States. Incorporated in 1963, it is an important commercial fishing port on Nushagak Bay. As of the 2020 ...

, when a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter he and several others were flying in crashed

"Crashed" is the third U.S. rock single, (the fifth overall), from the band Daughtry's debut album. It was released only to U.S. rock stations on September 5, 2007. Upon its release the song got adds at those stations, along with some Alternativ ...

en route to a private fishing lodge. Former NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe and future NASA Deputy Administrator James Morhard

James Morhard (born 20 September 1956) is a former American government official who served as the Deputy Administrator of NASA under President Donald Trump.

Biography Early life and education

Morhard was born in Washington, DC. He received his ...

survived the crash.

Early life and career

Childhood and youth

Rootsweb.com. Retrieved on May 31, 2007. in a small cottage built by his paternal grandfather after the marriage of his parents, Gertrude S. (née Chancellor) and George A. Stevens. The family later lived in Chicago, where George Stevens was an accountant before losing his job during the Great Depression.Mitchell, Donald Craig. (2001). ''Take My Land, Take My Life: The Story of Congress's Historic Settlement of Alaska Native Land Claims, 1960–1971''. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, p. 220. Around this time, when Ted Stevens was six years old, his parents divorced, and Stevens and his three siblings went back to Indianapolis to reside with their paternal grandparents, followed shortly thereafter by their father, who developed problems with his eyes and went blind for several years. Stevens's mother moved to California and sent for Stevens's siblings as she could afford to, but Stevens stayed in Indianapolis helping to care for his father and a mentally disabled cousin, Patricia Acker, who also lived with the family. The only adult in the household with a job was Stevens's grandfather. Stevens helped to support the family by working as a newsboy, and would later remember selling many newspapers on March 1, 1932, when newspaper headlines blared the news of the Lindbergh kidnapping.

In 1934 Stevens's grandfather punctured a lung in a fall down a tall flight of stairs, contracted

In 1934 Stevens's grandfather punctured a lung in a fall down a tall flight of stairs, contracted pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

, and died. Stevens's father, George, died in 1957 in Tulsa

Tulsa () is the second-largest city in the state of Oklahoma and 47th-most populous city in the United States. The population was 413,066 as of the 2020 census. It is the principal municipality of the Tulsa Metropolitan Area, a region with ...

, Oklahoma, of lung cancer. Stevens and his cousin Patricia moved to Manhattan Beach, California

Manhattan Beach is a city in southwestern Los Angeles County, California, United States, on the Pacific coast south of El Segundo, west of Hawthorne and Redondo Beach, and north of Hermosa Beach. As of the 2010 census, the population was 35 ...

in 1938, by which time both of Stevens's grandparents had passed away, to live with Patricia's mother, Gladys Swindells. Stevens attended Redondo Union High School

Redondo Union High School (RUHS) is a public high school in Redondo Beach, California.

Redondo Union High School is a part of the Redondo Beach Unified School District.

All residents of Redondo Beach are zoned to Redondo Union. In addition, res ...

, participating in extracurricular activities including working on the school newspaper and becoming a member of a student theater group, a service society affiliated with the YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams (philanthropist), Georg ...

, and, during his senior year, the Lettermen's Society. Stevens also worked at jobs before and after school, but still had time for surfing with his friend Russell Green, son of the president of Signal Gas and Oil Company, who remained a close friend throughout Stevens's life.

Military service

After graduating from high school in 1942, Stevens enrolled at

After graduating from high school in 1942, Stevens enrolled at Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant, research university in Corvallis, Oregon. OSU offers more than 200 undergraduate-degree programs along with a variety of graduate and doctoral degree ...

to study engineering,Mitchell, 2001, p. 221. attending for a semester. With World WarII in progress, Stevens attempted to join the Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It include ...

and serve in naval aviation

Naval aviation is the application of Military aviation, military air power by Navy, navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft ...

, but failed the vision exam. He corrected his vision through a course of prescribed eye exercises, and in 1943 he was accepted into an Army Air Force Air Cadet program at Montana State College. After scoring near the top of an aptitude test for flight training, Stevens was transferred to preflight training in Santa Ana, California; he received his wings early in 1944.

Stevens served in the

Stevens served in the China-Burma-India theater

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces (including U.S. forces) in the CBI was off ...

with the Fourteenth Air Force

The Fourteenth Air Force (14 AF; Air Forces Strategic) was a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Space Command (AFSPC). It was headquartered at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

The command was responsible for the organizati ...

Transport Section, which supported the "Flying Tigers

The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China. Operating in 1941–1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States ...

", from 1944 to 1945. He and other pilots in the transport section flew C-46

The Curtiss C-46 Commando is a twin-engine transport aircraft derived from the Curtiss CW-20 pressurised high-altitude airliner design. Early press reports used the name "Condor III" but the Commando name was in use by early 1942 in company pub ...

and C-47

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota (RAF, RAAF, RCAF, RNZAF, and SAAF designation) is a military transport aircraft developed from the civilian Douglas DC-3 airliner. It was used extensively by the Allies during World War II and remained in f ...

transport plane

A cargo aircraft (also known as freight aircraft, freighter, airlifter or cargo jet) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is designed or converted for the carriage of cargo rather than passengers. Such aircraft usually do not incorporate passenger a ...

s, often without escort, mostly in support of Chinese units fighting the Japanese. Stevens received the Distinguished Flying Cross for flying behind enemy lines, the Air Medal

The Air Medal (AM) is a military decoration of the United States Armed Forces. It was created in 1942 and is awarded for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight.

Criteria

The Air Medal was establish ...

, and the Yuan Hai Medal awarded by the Chinese Nationalist government. He was discharged from the Army Air Forces in March 1946.

Higher education and law school

After the war, Stevens attended theUniversity of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a Normal school, teachers colle ...

(UCLA), where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and ...

in 1947. While at UCLA, he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon (), commonly known as ''DKE'' or ''Deke'', is one of the oldest fraternities in the United States, with fifty-six active chapters and five active colonies across North America. It was founded at Yale College in 1844 by fift ...

fraternity (Theta Rho chapter). He applied to law school at Stanford

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

and the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

, but on the advice of his friend Russell Green's father to "look East", he applied to Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

, which he ended up attending. Stevens's education was partly financed by the G.I. Bill

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in 1956, bu ...

; he made up the difference by selling his blood, borrowing money from an uncle, and working several jobs including one as a bartender in Boston. During the summer of 1949, Stevens was a research assistant in the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of California (now the Central District of California

The United States District Court for the Central District of California (in case citations, C.D. Cal.; commonly referred to as the CDCA or CACD) is a Federal trial court that serves over 19 million people in Southern and Central California, m ...

)."With the editors..." 64 ''Harvard Law Review'' vii (1950).Mitchell, 2001, p. 222.

While at Harvard, Stevens wrote a paper on maritime law which received honorable mention for the Addison Brown prize, a Harvard Law School award for the best essay by a student on a subject related to private international law

Conflict of laws (also called private international law) is the set of rules or laws a jurisdiction applies to a case, transaction, or other occurrence that has connections to more than one jurisdiction. This body of law deals with three broad t ...

or maritime law. The essay later became a ''Harvard Law Review

The ''Harvard Law Review'' is a law review published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'', the ''Harvard Law Review''s 2015 impact factor of 4.979 placed the journal first out of 143 ...

'' articleStevens, Theodore F. "Erie R.R. v. Tompkins and the Uniform General Maritime Law". 64 ''Harvard Law Review'' 88–112 (1950). whose scholarship Justice Jay Rabinowitz of the Alaska Supreme Court praised 45 years later, telling the ''Anchorage Daily News

The ''Anchorage Daily News'' is a daily newspaper published by the Binkley Co., and based in Anchorage, Alaska. It is the most widely read newspaper and news website (adn.com) in the state of Alaska.

The newspaper is headquartered in Anchorage, ...

'' in 1994 that the high court had issued a recent opinion citing the article. Stevens graduated from Harvard Law School in 1950.

Early legal career

After graduating, Stevens went to work in the Washington, D.C., law offices of Northcutt Ely.Whitney, David. (1994-08-09)"The road north: Needing work, Stevens borrows $600, answers call to Alaska."

''Anchorage Daily News''. Retrieved June 1, 2007. Twenty years earlier Ely had been executive assistant to Secretary of the Interior

Ray Lyman Wilbur

Ray Lyman Wilbur (April 13, 1875 – June 26, 1949) was an American medical doctor who served as the third president of Stanford University and was the 31st United States Secretary of the Interior.

Early life

Wilbur was born in Boonesboro, Io ...

during the Hoover administration,Ely, Northcutt. (December 16, 1994)"Doctor Ray Lyman Wilbur: Third President of Stanford & Secretary of the Interior."

Paper presented at the Fortnightly Club of Redlands, California, meeting #1530. Retrieved on June 5, 2007. and by 1950 headed a prominent law firm specializing in

natural resources

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

issues. One of Ely's clients, Emil Usibelli, founder of the Usibelli Coal Mine in Healy, Alaska,Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation. (2006)"Emil Usibelli (1893–1964)."

Retrieved on 2007-06-05. was trying to sell coal to the military, and Stevens was assigned to handle his legal affairs.

Marriage and family

Early in 1952, Stevens married Ann Mary Cherrington, a Democrat and the adopted daughter ofUniversity of Denver

The University of Denver (DU) is a private research university in Denver, Colorado. Founded in 1864, it is the oldest independent private university in the Rocky Mountain Region of the United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Univ ...

Chancellor Ben Mark Cherrington

Ben Mark Cherrington (November 1, 1885 – May 2, 1980) was Acting Chancellor at the University of Denver from October 1943 to February 1946. During his term of office as chancellor he added the School of Speech and the Hotel and Restaurant Manage ...

. She had graduated from Reed College

Reed College is a private university, private liberal arts college in Portland, Oregon. Founded in 1908, Reed is a residential college with a campus in the Eastmoreland, Portland, Oregon, Eastmoreland neighborhood, with Tudor style architecture ...

in Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populou ...

, and during Truman's administration had worked for the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nat ...

.

On December 4, 1978, the crash of a Learjet 25C on approach at Anchorage International Airport killed five of the seven aboard; Stevens survived (concussion

A concussion, also known as a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), is a head injury that temporarily affects brain functioning. Symptoms may include loss of consciousness (LOC); memory loss; headaches; difficulty with thinking, concentratio ...

, broken ribs), but his wife Ann didnot. Stevens would later state in an interview with the Anchorage Times "I can't remember anything that happened." Smiling, he added "I'm still here. It must be my Scots

Scots usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

* Scots language, a language of the West Germanic language family native to Scotland

* Scots people, a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland

* Scoti, a Latin na ...

blood." The building which houses the Alaska chapter of the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the desig ...

at 235 East Eighth Avenue in Anchorage

Anchorage () is the largest city in the U.S. state of Alaska by population. With a population of 291,247 in 2020, it contains nearly 40% of the state's population. The Anchorage metropolitan area, which includes Anchorage and the neighboring ...

is named in her memory; likewise a reading room at the Loussac Library.

Alaska Senate

The Alaska State Senate is the upper house in the Alaska Legislature, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Alaska. It convenes in the Alaska State Capitol in Juneau, Alaska and is responsible for making laws and confirming or rejecting gu ...

in 2001, where he served as the president of the state senate until the fall of 2006.

Ted Stevens remarried in 1980. He and his second wife, Catherine, had a daughter, Lily.

Stevens spent many years living at the Knik Arms, a six-story residential building constructed in 1950 on the western edge of downtown Anchorage. In his earlier years in the Senate, he would often point to this residence when trying to drive home the point that he was not of means and had not achieved such through his Senate service.

Stevens's last home was in Girdwood, a ski resort community near the southern edge of Anchorage's city limits, about by road from downtown

''Downtown'' is a term primarily used in North America by English speakers to refer to a city's sometimes commercial, cultural and often the historical, political and geographic heart. It is often synonymous with its central business distric ...

. Originally purchased as a vacation home, Stevens later lived there full-time.

Prostate cancer

Stevens was a survivor ofprostate cancer

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancerous tumor worldwide and is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men. The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system that su ...

and had publicly disclosed his cancer. He was nominated for the first Golden Glove Awards for Prostate Cancer by the National Prostate Cancer Coalition (NPCC). He advocated the creation of the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program for Prostate Cancer at the Department of Defense, which has funded nearly $750million for prostate cancer research. Stevens was a recipient of the Presidential Citation by the American Urological Association

The American Urological Association (AUA) is a professional association in the United States for urology professionals. It has its headquarters at the William P. Didusch Center for Urologic History in Maryland.

AUA works with many international or ...

for significantly promoting urology causes.

Early Alaska career

In 1952, while still working for Northcutt Ely, Stevens volunteered for the presidential campaign of Dwight D. Eisenhower, writing position papers for the campaign on western water law and lands. By the time Eisenhower won the election that November, Stevens had acquired contacts who told him, "We want you to come over to Interior." Stevens left his job with Ely, but a job in the Eisenhower administration didn't come through as a result of a temporary hiring freeze instituted by Eisenhower in an effort to reduce spending. Instead, Stevens was offered a job with theFairbanks, Alaska

Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the po ...

, law firm of Emil Usibelli's Alaska attorney, Charles Clasby, whose firm (Collins &Clasby) had just lost one of its attorneys. Stevens and his wife had met and liked both Usibelli and Clasby, and decided to make the move. Loading up their 1947 BuickMitchell, 2001, p. 223. and traveling on a $600 loan from Clasby, they drove across country from Washington, D.C., and up the Alaska Highway

Ted Stevens News

from

Obituary

from

Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes Held in the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States Together With Memorial Services in Honor of Ted Stevens, Late a Senator from Alaska, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, Second Session

Ted Stevens Paper Projects

from Alaska and Polar Regions Collections of Elmer E. Rasmuson and BioSciences Libraries *

Ted Stevens

at ''100 Years of Alaska's Legislature''

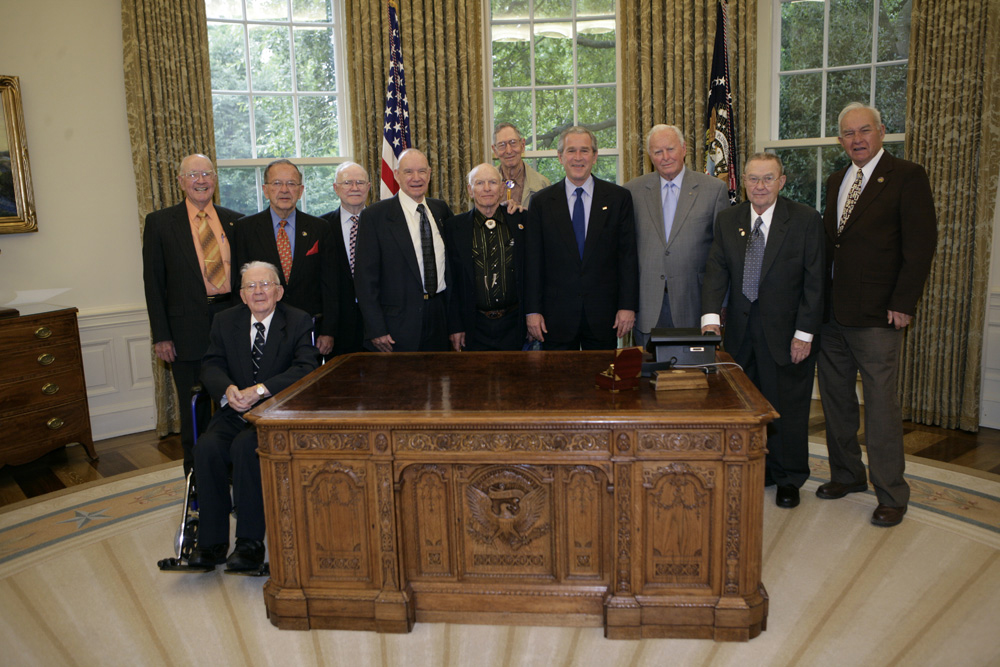

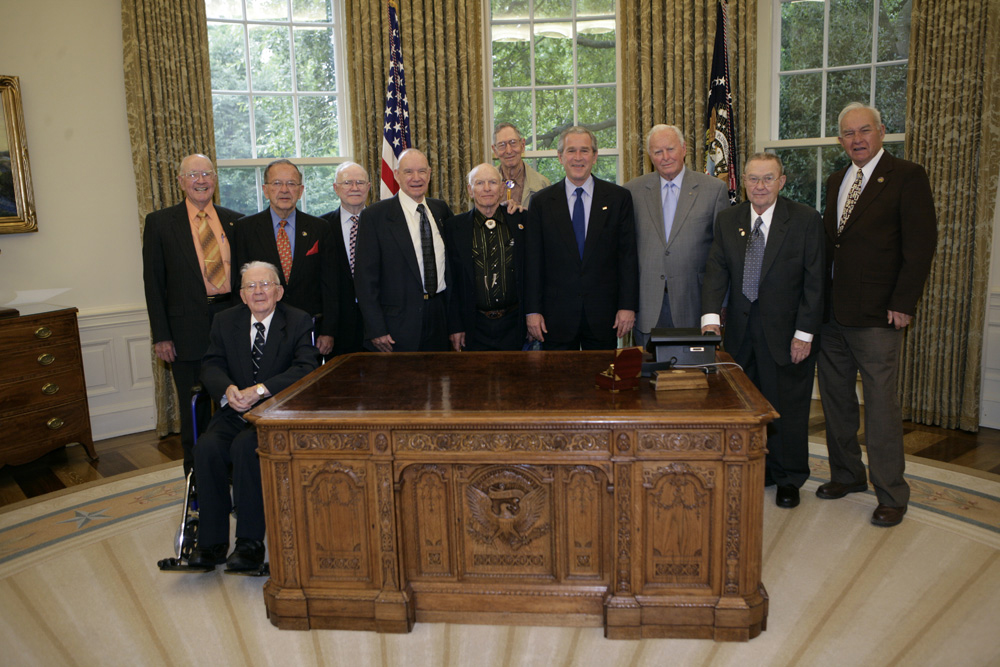

President Bush: Stevens Loved Alaska APRN. May 17, 2017.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stevens, Ted 1923 births 2010 deaths 21st-century American politicians Accidental deaths in Alaska Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents in the United States Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Harvard Law School alumni Republican Party members of the Alaska House of Representatives Overturned convictions in the United States Politicians from Anchorage, Alaska Politicians from Fairbanks, Alaska People from Manhattan Beach, California Politicians from Indianapolis Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate Recipients of the Air Medal Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) Recipients of the Olympic Order Republican Party United States senators from Alaska Survivors of aviation accidents or incidents United States Army Air Forces officers United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II United States Attorneys for the District of Alaska University of California, Los Angeles alumni Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 2010 Military personnel from Fairbanks, Alaska Military personnel from Anchorage, Alaska Military personnel from Indiana 20th-century American Episcopalians Military personnel from California Solicitors of the United States Department of the Interior

Ted Stevens News

from

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

Obituary

from

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes Held in the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States Together With Memorial Services in Honor of Ted Stevens, Late a Senator from Alaska, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, Second Session

Ted Stevens Paper Projects

from Alaska and Polar Regions Collections of Elmer E. Rasmuson and BioSciences Libraries *

Ted Stevens

at ''100 Years of Alaska's Legislature''

President Bush: Stevens Loved Alaska APRN. May 17, 2017.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stevens, Ted 1923 births 2010 deaths 21st-century American politicians Accidental deaths in Alaska Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents in the United States Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Harvard Law School alumni Republican Party members of the Alaska House of Representatives Overturned convictions in the United States Politicians from Anchorage, Alaska Politicians from Fairbanks, Alaska People from Manhattan Beach, California Politicians from Indianapolis Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate Recipients of the Air Medal Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) Recipients of the Olympic Order Republican Party United States senators from Alaska Survivors of aviation accidents or incidents United States Army Air Forces officers United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II United States Attorneys for the District of Alaska University of California, Los Angeles alumni Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 2010 Military personnel from Fairbanks, Alaska Military personnel from Anchorage, Alaska Military personnel from Indiana 20th-century American Episcopalians Military personnel from California Solicitors of the United States Department of the Interior