The Structure And Distribution Of Coral Reefs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836'', was published in 1842 as

''The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836'', was published in 1842 as

By the time that the ''Beagle'' set out for the

By the time that the ''Beagle'' set out for the

FitzRoy's instructions set detailed requirements for geological survey of a circular

FitzRoy's instructions set detailed requirements for geological survey of a circular

The first three chapters describe the various types of

The first three chapters describe the various types of

In assessing the geology of the reef, Darwin showed his remarkable ability to collect facts and find patterns to reconstruct geological history on the basis of the very limited evidence available. He gave attention to the smallest detail. Having heard that parrotfish browsed on the living coral, he dissected specimens to find finely ground coral in their intestines. He concluded that such fish, and coral eating invertebrates such as

In assessing the geology of the reef, Darwin showed his remarkable ability to collect facts and find patterns to reconstruct geological history on the basis of the very limited evidence available. He gave attention to the smallest detail. Having heard that parrotfish browsed on the living coral, he dissected specimens to find finely ground coral in their intestines. He concluded that such fish, and coral eating invertebrates such as

''The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836'', was published in 1842 as

''The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836'', was published in 1842 as Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's first monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

, and set out his theory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

of the formation of coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s and atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical parts of the oceans and seas where corals can develop. Most ...

s. He conceived of the idea during the voyage of the ''Beagle'' while still in South America, before he had seen a coral island, and wrote it out as HMS ''Beagle'' crossed the Pacific Ocean, completing his draft by November 1835. At the time there was great scientific interest in the way that coral reefs formed, and Captain Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

's orders from the Admiralty included the investigation of an atoll as an important scientific aim of the voyage. FitzRoy chose to survey the Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean. The results supported Darwin's theory that the various types of coral reefs and atolls could be explained by uplift and subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

of vast areas of the Earth's crust under the oceans.

The book was the first volume of three Darwin wrote about the geology he had investigated during the voyage, and was widely recognised as a major scientific work that presented his deductions from all the available observations on this large subject. In 1853, Darwin was awarded the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

's Royal Medal for the monograph and for his work on barnacle

Barnacles are arthropods of the subclass (taxonomy), subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacean, Crustacea. They are related to crabs and lobsters, with similar Nauplius (larva), nauplius larvae. Barnacles are exclusively marine invertebra ...

s. Darwin's theory that coral reefs formed as the islands and surrounding areas of crust subsided has been supported by modern investigations, and is no longer disputed, while the cause of the subsidence and uplift of areas of crust has continued to be a subject of discussion.

Theory of coral atoll formation

When the ''Beagle'' set out in 1831, the formation ofcoral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical parts of the oceans and seas where corals can develop. Most ...

s was a scientific puzzle. Advance notice of her sailing, given in the '' Athenaeum'' of 24 December, described investigation of this topic as "the most interesting part of the ''Beagles survey" with the prospect of "many points for investigation of a scientific nature beyond the mere occupation of the surveyor. In 1824 and 1825, French naturalists Quoy and Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

had observed that the coral organisms

An organism is any living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have been pr ...

lived at relatively shallow depths, but the islands appeared in deep oceans. In books that were taken on the ''Beagle'' as references, Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the ...

, Frederick William Beechey and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

had published the opinion that the coral had grown on underwater mountains or volcanoes, with atolls taking the shape of underlying volcanic crater

A volcanic crater is an approximately circular depression in the ground caused by volcanic activity. It is typically a bowl-shaped feature containing one or more vents. During volcanic eruptions, molten magma and volcanic gases rise from an ...

s. The Admiralty instructions for the voyage stated:

As a student at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

in 1827, Darwin learnt about marine invertebrate

Marine invertebrates are invertebrate animals that live in marine habitats, and make up most of the macroscopic life in the oceans. It is a polyphyletic blanket term that contains all marine animals except the marine vertebrates, including the ...

s while assisting the investigations of the anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 – 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

, and during his last year at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

in 1831, he had studied geology under Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick FRS (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did ...

. So when he was unexpectedly offered a place on the ''Beagle'' expedition, as a gentleman naturalist he was well suited to FitzRoy's aim of having a companion able to examine geology on land while the ship's complement carried out its hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore wind farms, offshore oil exploration and drilling and related activities. Surveys may als ...

. FitzRoy gave Darwin the first volume of Lyell's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...

'' before they left. On their first stop ashore at St Jago island in January 1832, Darwin saw geological formations which he explained using Lyell's uniformitarian

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

concept that forces still in operation made land slowly rise or fall over immense periods of time, and thought that he could write his own book on geology. Lyell's first volume included a brief outline of the idea that atolls were based on volcanic craters, and the second volume, which was sent to Darwin during the voyage, gave more detail. Darwin received it in November 1832.

While the ''Beagle'' surveyed the coasts of South America from February 1832 to September 1835, Darwin made several trips inland and found extensive evidence that the continent was gradually rising. After witnessing an erupting volcano from the ship, he experienced the 1835 Concepción earthquake

The 1835 Concepción earthquake was an earthquake that occurred near the neighboring cities of Concepción and Talcahuano in Chile on 20 February at 11:30 local time (15:30 UTC), and had an estimated magnitude of about 8.5 . The earthquake tr ...

. In the following months he speculated that as the land was uplifted, large areas of the ocean bed subsided. It struck him that this could explain the formation of atolls.

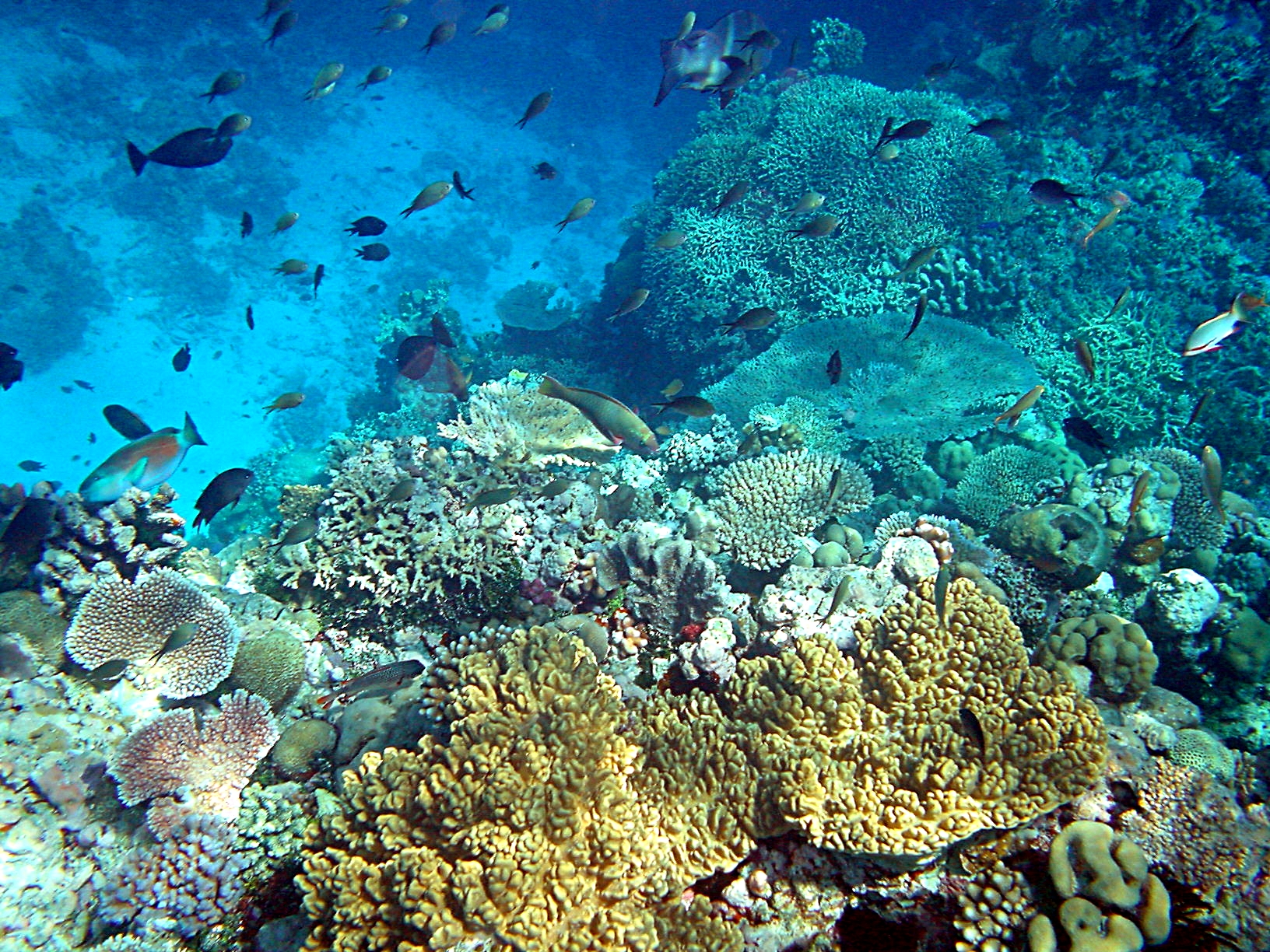

Darwin's theory followed from his understanding that coral polyps thrive in the clean seas of the tropics where the water is agitated, but can only live within a limited depth of water, starting just below low tide. Where the level of the underlying land stays the same, the corals grow around the coast to form what he called fringing reefs, and can eventually grow out from the shore to become a barrier reef. Where the land is rising, fringing reefs can grow around the coast, but coral raised above sea level dies and becomes white limestone. If the land subsides slowly, the fringing reefs keep pace by growing upwards on a base of dead coral, and form a barrier reef enclosing a lagoon between the reef and the land. A barrier reef can encircle an island, and once the island sinks below sea level a roughly circular atoll of growing coral continues to keep up with the sea level, forming a central lagoon. Should the land subside too quickly or sea level rise too fast, the coral dies as it is below its habitable depth.

Darwin's investigations to test his theory

Galápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands () are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Eastern Pacific, located around the equator, west of the mainland of South America. They form the Galápagos Province of the Republic of Ecuador, with a population of sli ...

on 7 September 1835, Darwin had thought out the essentials of his theory of atoll formation. While he no longer favoured the concept that atolls formed on submerged volcanos, he noted some points on these islands which supported that idea: 16 volcanic craters resembled atolls in being raised slightly more on one side, and five hills appeared roughly equal in height. He then considered a topic which was compatible with either theory, the lack of coral reefs around the Galápagos Islands. One possibility was a lack of calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime (mineral), lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of Science, scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcare ...

matter around the islands, but his main proposal, which FitzRoy had suggested to him, was that the seas were too cold. As they sailed on, Darwin took note of the records of sea temperature kept in the ship's "Weather Journal".

He had his first glimpse of coral atolls as they passed Honden Island on 9 November and sailed on through the Low or Dangerous Archipelago (Tuamotus

The Tuamotu Archipelago or the Tuamotu Islands (, officially ) are a French Polynesian chain of just under 80 islands and atolls in the southern Pacific Ocean. They constitute the largest chain of atolls in the world, extending (from northwest to ...

). Arriving at Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

on 15 November, Darwin saw it "encircled by a Coral reef separated from the shore by channels & basins of still water". He climbed the hills of Tahiti, and was strongly impressed by the sight across to the island of Eimeo, where "The mountains abruptly rise out of a glassy lake, which is separated on all sides, by a narrow defined line of breakers, from the open sea. – Remove the central group of mountains, & there remains a Lagoon Isd." Rather than recording his findings about the coral reefs in his notes about the island, he wrote them up as the first full draft of his theory, an essay titled ''Coral Islands'', dated 1835. They left Tahiti on 3 December, and Darwin probably wrote his essay as they sailed towards New Zealand where they arrived on 21 December. He described the polyp species building the coral on the barrier wall, flourishing in the heavy surf of breaking waves particularly on the windward side, and speculated on reasons that corals in the calm lagoon did not grow so high. He concluded with a "remark that the general horizontal uplifting which I have proved has & is now raising upwards the greater part of S. America & as it would appear likewise of N. America, would of necessity be compensated by an equal subsidence in some other part of the world."

Keeling Islands

FitzRoy's instructions set detailed requirements for geological survey of a circular

FitzRoy's instructions set detailed requirements for geological survey of a circular coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical parts of the oceans and seas where corals can develop. Most ...

to investigate how coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

s formed, particularly if they rose from the bottom of the sea or from the summits of extinct volcanoes, and to assess the effects of tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s by measurement with specially constructed gauges. FitzRoy chose the Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean, and on arrival there on 1 April 1836, the entire crew set to work, first erecting FitzRoy's new design of a tide gauge that allowed readings to be taken from the shore. Boats were sent all around the island to carry out the survey, and despite being impeded by strong winds, they took numerous soundings to establish depths around the atoll and in the lagoon. FitzRoy noted the smooth and solid rock-like outer wall of the atoll, with most life thriving where the surf was most violent. He had great difficulty in establishing the depth reached by living coral, as pieces were hard to break off and the small anchors, hooks, grappling irons, and chains they used were all snapped off by the swell as soon as they tried to pull them up. He had more success using a sounding line with a bell-shaped lead weight armed with tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton suet, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton suet. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain technical criteria, inc ...

hardened with lime; this would be indented by any shape that it struck to give an exact impression of the bottom; it would also collect any fragments of coral or grains of sand.

These soundings were taken personally by FitzRoy, and the tallow from each sounding was cut off and taken on board to be examined by Darwin. The impressions taken on the steep outside slope of the reef were marked with the shapes of living corals, and otherwise were clean down to about 10 fathom

A fathom is a unit of length in the imperial and the U.S. customary systems equal to , used especially for measuring the depth of water. The fathom is neither an international standard (SI) unit, nor an internationally accepted non-SI unit. H ...

s (18 m); then at increasing depths, the tallow showed fewer such impressions and collected more grains of sand until it was evident that there were no living corals below about 20–30 fathom

A fathom is a unit of length in the imperial and the U.S. customary systems equal to , used especially for measuring the depth of water. The fathom is neither an international standard (SI) unit, nor an internationally accepted non-SI unit. H ...

s (36–55 m). Darwin carefully noted the location of the different types of coral around the reef and in the lagoon. In his diary, he described, "examining the very interesting yet simple structure & origin of these islands. The water being unusually smooth, I waded in as far as the living mounds of coral on which the swell of the open sea breaks. In some of the gullies & hollows, there were beautiful green & other colored fishes, & the forms & tints of many of the Zoophites were admirable. It is excusable to grow enthusiastic over the infinite numbers of organic beings with which the sea of the tropics, so prodigal of life, teems", though he cautioned against the "rather exuberant language" used by some naturalists.

As they left the islands after eleven days, Darwin wrote out a summary of his theory in his diary:

Publication of theory

When the ''Beagle'' returned on 2 October 1836, Darwin was already a celebrity in scientific circles, as in December 1835University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

Professor of Botany John Stevens Henslow had fostered his former pupil's reputation by giving selected naturalists a pamphlet of Darwin's geological letters. Charles Lyell eagerly met Darwin for the first time on 29 October, enthusiastic about the support this gave to his uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

, and in May wrote to John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work. ...

that he was "very full of Darwin's new theory of Coral Islands, and have urged Whewell to make him read it at our next meeting. I must give up my volcanic crater theory for ever, though it cost me a pang at first, for it accounted for so much... the whole theory is knocked on the head, and the annular shape and central lagoon have nothing to do with volcanoes, nor even with a crateriform bottom.... Coral islands are the last efforts of drowning continents to lift their heads above water. Regions of elevation and subsidence in the ocean may be traced by the state of the coral reefs." Darwin presented his findings and theory in a paper which he read to the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

on 31 May 1837.

Darwin's first literary project was his ''Journal and Remarks'' on the natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

of the expedition, now known as ''The Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

''. In it he expanded his diary notes into a section on this theory, emphasising how the presence or absence of coral reefs and atolls can show whether the ocean bed is elevating or subsiding. At the same time he was privately speculating intensively about transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

, and taking on other projects. He finished writing out his journal around the end of September, but then had the work of correcting proofs.

His tasks included finding experts to examine and report on his collections from the voyage. Darwin proposed to edit these reports, writing his own forewords and notes, and used his contacts to lobby for government sponsorship of publication of these findings as a large book. When a Treasury grant of £1,000 was allocated at the end of August 1837, Darwin stretched the project to include the geology book that he had conceived in April 1832 at the first landfall in the voyage. He selected Smith, Elder & Co. as the publisher, and gave them unrealistic commitments on the timing of providing the text and illustrations. He assured the Treasury that the work would be good value, as the publisher would only require a small commission profit, and he himself would have no profit. From October he planned what became the multi-volume '' Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle'' on his collections, and began writing about the geology of volcanic islands.

In January 1838, Smith, Elder & Co. advertised the first part of Darwin's geology book, ''Geological observations on volcanic islands and coral formations'', as a single octavo volume to be published that year. By the end of the month Darwin thought that his geology was "covering so much paper, & will take so much time" that it could be split into separate volumes (eventually ''Coral reefs'' was published first, followed by ''Volcanic islands'' in 1844, and ''South America'' in 1846). He also doubted that the treasury funds could cover all the geological writings. The first part of the zoology was published in February 1838, but Darwin found it a struggle to get the experts to produce their reports on his collections, and overwork led to illness. After a break to visit Scotland, he wrote up a major paper on the geological "roads" of Glen Roy. On 5 October 1838 he noted in his diary, "Began Coral Paper: requires much reading".

In November 1838 Darwin proposed to his cousin Emma, and they married in January 1839. As well as his other projects he continued to work on his ideas of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

as his "prime hobby", but repeated delays were caused by his illness. He sporadically restarted work on ''Coral Reefs'', and on 9 May 1842 wrote to Emma, telling her he was

Publication and subsequent editions

''The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs'' was published in May 1842, priced at 15shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currency, currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 1 ...

s, and was well received. A second edition was published in 1874, extensively revised and rewritten to take into account James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcano, volcanic activity, and the ...

's 1872 publication ''Corals and Coral Islands'', and work by Joseph Jukes.

Structure of book

The book has a tightly logical structure, and presents a bold argument. Illustrations are used as an integral part of the argument, with numerous detailed charts and one large world map marked in colour showing all reefs known at that time. A brief introduction sets out the aims of the book.coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

, each chapter starting with a section giving a detailed description of the reef Darwin had most information about, which he presents as a typical example of the type. Subsequent sections in each chapter then describe other reefs in comparison with the typical example. In the first chapter, Darwin describes atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical parts of the oceans and seas where corals can develop. Most ...

s and lagoon islands, taking as his typical example his own detailed findings and the ''Beagle'' survey findings on the Keeling Islands. The second chapter similarly describes a typical barrier reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

C ...

then compares it to others, and the third chapter gives a similar description of what Darwin called fringing or shore reefs. Having described the principal kinds of reef in detail, his finding was that the actual surface of the reef did not differ much. An atoll differs from an encircling barrier reef only in lacking the central island, and a barrier reef differs from a fringing reef only in its distance from the land and in enclosing a lagoon.

The fourth chapter on the distribution and growth of coral reefs examines the conditions in which they flourish, their rate of growth and the depths at which the reef building polyps can live, showing that they can only flourish at a very limited depth. In the fifth chapter he sets out his theory as a unified explanation for the findings of the previous chapters, overcoming the difficulties of treating the various kinds of reef as separate and the problem of reliance on the improbable assumption that underwater mountains just happened to be at the exact depth below sea level, by showing how barrier reefs and then atolls form as the land subsides, and fringing reefs are found along with evidence that the land is being elevated. This chapter ends with a summary of his theory illustrated with two woodcuts each showing two different stages of reef formation in relation to sea level.

In the sixth chapter he examines the geographical distribution of types of reef and its geological implications, using the large coloured map of the world to show vast areas of atolls and barrier reefs where the ocean bed was subsiding with no active volcanos, and vast areas with fringing reefs and volcanic outbursts where the land was rising. This chapter ends with a recapitulation which summarises the findings of each chapter and concludes by describing the global image as "a magnificent and harmonious picture of the movements, which the crust of the earth has within a late period undergone". A large appendix gives a detailed and exhaustive description of all the information he had been able to obtain on the reefs of the world.

This logical structure can be seen as a prototype for the organisation of ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', presenting the detail of various aspects of the problem, then setting out a theory explaining the phenomena, followed by a demonstration of the wider explanatory power of the theory. Unlike the ''Origin'' which was hurriedly put together as an abstract of his planned "big book", ''Coral Reefs'' is fully supported by citations and material gathered together in the Appendix. ''Coral Reefs'' is arguably the first volume of Darwin's huge treatise on his philosophy of nature, like his succeeding works showing how slow gradual change can account for the history of life. In presenting types of reef as an evolutionary series it demonstrated a rigorous methodology for historical sciences, interpreting patterns visible in the present as the results of history. In one passage he presents a particularly Malthusian view of a struggle for survival – "In an old-standing reef, the corals, which are so different in kind on different parts of it, are probably all adapted to the stations they occupy, and hold their places, like other organic beings, by a struggle one with another, and with external nature; hence we may infer that their growth would generally be slow, except under peculiarly favourable circumstances."

Reception

Having successfully completed and published the other books on the geology and zoology of the voyage, Darwin spent eight years on a major study ofbarnacle

Barnacles are arthropods of the subclass (taxonomy), subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacean, Crustacea. They are related to crabs and lobsters, with similar Nauplius (larva), nauplius larvae. Barnacles are exclusively marine invertebra ...

s. Two volumes on ''Lepadidae'' (goose barnacle

Goose barnacles, also called percebes, turtle-claw barnacles, stalked barnacles, gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles form ...

s) were published in 1851. While he was still working on two volumes on the remaining barnacles, Darwin learnt to his delight in 1853 that the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

had awarded him the Royal Medal for Natural Science. Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

wrote telling him that "Pordock proposed you for the Coral Islands & Lepadidae, Bell followed seconding on the Lepadidae alone, & then followed such a shout of paeans for the Barnacles that you would have miledto hear."

Late 19th-century controversy and tests of the theory

A major scientific controversy over the origin of coral reefs took place in the late 19th century, between supporters of Darwin's theory (such as the American geologistJames Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcano, volcanic activity, and the ...

, who early in his career had seen coral reefs in Hawaii and Fiji during the 1838–42 United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

), and those who supported a rival theory put forward by the Scottish oceanographer John Murray, who participated in the 1872–76 Challenger expedition

The ''Challenger'' expedition of 1872–1876 was a scientific programme that made many discoveries to lay the foundation of oceanography. The expedition was named after the naval vessel that undertook the trip, .

The expedition, initiated by W ...

. Murray's theory challenged Darwin's notion of subsidence, proposing instead that coral reefs formed when accumulating mounds of calcareous marine sediments reached the shallow depths that could support the growth of corals. Amongst Murray's supporters was the independently wealthy American scientist Alexander Agassiz, who financed and undertook several expeditions to the Caribbean, Pacific and Indian Ocean regions to examine coral reefs in search of evidence to support Murray's theory, and to discredit Darwin.Dobbs, D. (2005): ''Reef Madness: Charles Darwin, Alexander Agassiz, and the Meaning of Coral''. Pantheon Books, New York.

A series of expeditions to test Darwin's theory by drilling on Funafuti

Funafuti is an atoll, comprising numerous islets, that serves as the capital of Tuvalu. As of the 2017 census, it has a population of 6,320 people. More people live in Funafuti than the rest of Tuvalu combined, with it containing approximately 6 ...

atoll in the Ellice Islands (now part of Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( ) is an island country in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean, about midway between Hawaii and Australia. It lies east-northeast of the Santa Cruz Islands (which belong to the Solomon Islands), northeast of Van ...

) was conducted by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

of London for the purpose of investigating whether basalt or traces of shallow water organisms could be found at depth in the coral. Drilling occurred in 1896, 1897 and 1898, attaining a final depth of , still in coral. Professor Edgeworth David

Sir Tannatt William Edgeworth David (28 January 1858 – 28 August 1934) was a Welsh Australian geologist, Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Antarctic explorer, and military veteran. He was knighted for his role in World War 1.

A hou ...

of the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD) is a public university, public research university in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in both Australia and Oceania. One of Australia's six sandstone universities, it was one of the ...

was a member of the 1896 expedition and leader of the 1897 expedition. At the time these results were regarded as inconclusive and it was not until the 1950s when, prior to carrying out nuclear bomb tests on Eniwetok

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; , , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with its 296 people (as of 2021) forms a legi ...

, deep exploratory drilling through of coral to the underlying basalt finally vindicated Darwin's theory. However, the geologic history of atolls is more complex than Darwin (1842) and Davis (1920 & 1928) envisioned.

Darwin's findings and later views

Darwin's interest on the biology of reef organisms was focussed on aspects related to his geological idea of subsidence; in particular, he was looking for confirmation that the reef building organisms could only live at shallow depths. FitzRoy's soundings at the Keeling Islands gave a depth limit for live coral of about , and taking into account numerous observations by others, Darwin worked with a probable limit of . Later findings suggest a limit of around 100 m, still a small fraction of the depth of the ocean floor at 3,000–5,000 m. Darwin recognised the importance ofred algae

Red algae, or Rhodophyta (, ; ), make up one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae. The Rhodophyta comprises one of the largest Phylum, phyla of algae, containing over 7,000 recognized species within over 900 Genus, genera amidst ongoing taxon ...

, and he reviewed other organisms that could have helped to build the reefs. He thought they lived at similarly shallow depths, but banks formed at greater depths were found in the 1880s. Darwin reviewed the distribution of different species of coral across a reef. He thought that the seaward reefs most exposed to wind and waves were formed by massive corals and red algae; this would be the most active area of reef growth and so would cause a tendency for reefs to grow outwards once they reach sea level. He believed that higher temperatures and the calmer water of the lagoons favoured the greatest coral diversity. These ecological ideas are still current, and research on the details continues.

In assessing the geology of the reef, Darwin showed his remarkable ability to collect facts and find patterns to reconstruct geological history on the basis of the very limited evidence available. He gave attention to the smallest detail. Having heard that parrotfish browsed on the living coral, he dissected specimens to find finely ground coral in their intestines. He concluded that such fish, and coral eating invertebrates such as

In assessing the geology of the reef, Darwin showed his remarkable ability to collect facts and find patterns to reconstruct geological history on the basis of the very limited evidence available. He gave attention to the smallest detail. Having heard that parrotfish browsed on the living coral, he dissected specimens to find finely ground coral in their intestines. He concluded that such fish, and coral eating invertebrates such as Holothuroidea

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea ( ). They are benthic marine animals found on the sea floor worldwide, and the number of known holothuroid species worldwide is about 1,786, with the greatest number being in the Asia ...

, could account for the banks of fine grained mud he found at the Keeling Islands; it showed also "that there are living checks to the growth of coral-reefs, and that the almost universal law of 'consume and be consumed,' holds good even with the polypifers forming those massive bulwarks, which are able to withstand the force of the open ocean."

His observations on the part played by organisms in the formation of the various features of reefs anticipated later studies. To establish the thickness of coral barrier reefs, he relied on the old nautical rule of thumb to project the slope of the land to that below sea level, and then applied his idea that the coral reef would slope much more steeply than the underlying land. He was fortunate to guess that the maximum depth of coral would be around , as the first test bores conducted by the United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

on Enewetak Atoll in 1952 drilled down through of coral before reaching the volcanic foundations. In Darwin's time no comparable thickness of fossil coral had been found on the continents, and when this was raised as a criticism of his theory neither he nor Lyell could find a satisfactory explanation. It is now thought that fossil reefs are usually broken up by tectonic movements, but at least two continental fossil reef complexes have been discovered to be about thick. While these findings have confirmed his argument that the islands were subsiding, his other attempts to show evidence of subsidence have been superseded by the discovery that glacial

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

effects can cause changes in sea level.

In Darwin's global hypothesis, vast areas where the seabed was being elevated were marked by fringing reefs, sometimes around active volcanoes, and similarly huge areas where the ocean floor was subsiding were indicated by barrier reefs or atolls based on inactive volcanoes. These views received general support from deep sea drilling results in the 1980s. His idea that rising land would be balanced by subsidence in ocean areas has been superseded by plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

, which he did not anticipate.

See also

* Formation of coral reefs * Darwin's paradox * List of reefs * Zimmerman's Competing Theory of Reef FormationNotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Structure And Distribution of Coral Reefs, The Books by Charles Darwin 1842 books 1874 books Geology books Evolutionary biology literature Biology books English non-fiction books 1840s in science 1840s in the environment 1874 in the environment English-language non-fiction books