The Oxford Imps on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The University of Oxford is a

The new learning of the

The new learning of the

The university is a "city university" in that it does not have a main campus; instead, colleges, departments, accommodation, and other facilities are scattered throughout central Oxford and in some other areas of the city. The Science Area, in which most science departments are located, is the area that bears closest resemblance to a campus. There is a ten-acre (4-hectare)

The university is a "city university" in that it does not have a main campus; instead, colleges, departments, accommodation, and other facilities are scattered throughout central Oxford and in some other areas of the city. The Science Area, in which most science departments are located, is the area that bears closest resemblance to a campus. There is a ten-acre (4-hectare)

The university's formal head is the

The university's formal head is the

The combined endowment figure of £8.708 billion makes Oxford hold the largest endowment of any university in the UK. The college figure does not reflect all the assets held by the colleges as their accounts do not include the cost or value of many of their main sites or heritage assets such as works of art or libraries.

The central University's endowment, along with some of the colleges', is managed by the university's wholly-owned endowment management office, Oxford University Endowment Management, formed in 2007. The university used to maintain substantial investments in fossil fuel companies. However, in April 2020, the university committed to divest from direct investments in fossil fuel companies and to require indirect investments in fossil fuel companies be subjected to the Oxford Martin Principles.

The university was one of the first in the UK to raise money through a major public fundraising campaign, the

The combined endowment figure of £8.708 billion makes Oxford hold the largest endowment of any university in the UK. The college figure does not reflect all the assets held by the colleges as their accounts do not include the cost or value of many of their main sites or heritage assets such as works of art or libraries.

The central University's endowment, along with some of the colleges', is managed by the university's wholly-owned endowment management office, Oxford University Endowment Management, formed in 2007. The university used to maintain substantial investments in fossil fuel companies. However, in April 2020, the university committed to divest from direct investments in fossil fuel companies and to require indirect investments in fossil fuel companies be subjected to the Oxford Martin Principles.

The university was one of the first in the UK to raise money through a major public fundraising campaign, the

In common with most British universities, prospective undergraduate students apply through the

In common with most British universities, prospective undergraduate students apply through the

There are many opportunities for students at Oxford to receive financial help during their studies. The Oxford Opportunity Bursaries, introduced in 2006, are university-wide means-based bursaries available to any British undergraduate, with a total possible grant of £10,235 over a 3-year degree. In addition, individual colleges also offer bursaries and funds to help their students. For graduate study, there are many scholarships attached to the university, available to students from all sorts of backgrounds, from

There are many opportunities for students at Oxford to receive financial help during their studies. The Oxford Opportunity Bursaries, introduced in 2006, are university-wide means-based bursaries available to any British undergraduate, with a total possible grant of £10,235 over a 3-year degree. In addition, individual colleges also offer bursaries and funds to help their students. For graduate study, there are many scholarships attached to the university, available to students from all sorts of backgrounds, from

Oxford maintains a number of museums and galleries, open for free to the public. The

Oxford maintains a number of museums and galleries, open for free to the public. The

Due to its age and its social and academic status, the University of Oxford is considered to be one of Britain's most prestigious or elite universities and to form, along with the

Due to its age and its social and academic status, the University of Oxford is considered to be one of Britain's most prestigious or elite universities and to form, along with the

Academic dress is required for examinations, matriculation, disciplinary hearings, and when visiting university officers. A referendum held among the Oxford student body in 2015 showed 76% against making it voluntary in examinations – 8,671 students voted, with the 40.2% turnout the highest ever for a UK student union referendum. This was widely interpreted by students as being a vote not so much on making subfusc voluntary, but, in effect, on abolishing it by default, in that if a minority of people came to exams without subfusc, the rest would soon follow. In July 2012 the regulations regarding academic dress were modified to be more inclusive to transgender people.

'Trashing' is a tradition of spraying those who just finished their last examination of the year with alcohol, flour and confetti. The sprayed student stays in the academic dress worn to the exam. The custom began in the 1970s when friends of students taking their finals waited outside Oxford's

Academic dress is required for examinations, matriculation, disciplinary hearings, and when visiting university officers. A referendum held among the Oxford student body in 2015 showed 76% against making it voluntary in examinations – 8,671 students voted, with the 40.2% turnout the highest ever for a UK student union referendum. This was widely interpreted by students as being a vote not so much on making subfusc voluntary, but, in effect, on abolishing it by default, in that if a minority of people came to exams without subfusc, the rest would soon follow. In July 2012 the regulations regarding academic dress were modified to be more inclusive to transgender people.

'Trashing' is a tradition of spraying those who just finished their last examination of the year with alcohol, flour and confetti. The sprayed student stays in the academic dress worn to the exam. The custom began in the 1970s when friends of students taking their finals waited outside Oxford's

The Oxford Union (distinct from Oxford University Student Union) is an independent debating society which hosts weekly debates and high-profile speakers. Party political groups include Oxford University Conservative Association and Oxford University Labour Club. Most academic areas have student societies of some form, for example the Oxford University Scientific Society, Scientific Society.

There are two weekly student newspapers: the independent ''Cherwell (newspaper), Cherwell'' and OUSU's ''The Oxford Student''. Other publications include the Isis magazine, ''Isis'' magazine, the satirical ''The Oxymoron, Oxymoron'', the graduate ''The Oxonian Review of Books, Oxonian Review'', the ''Oxford Political Review'', and the online only newspaper ''The Oxford Blue''. The Campus radio, student radio station is Oxide Radio.

Sport is played between college teams, in tournaments known as cuppers (the term is also used for some non-sporting competitions). In particular, much attention is given to the termly intercollegiate rowing regattas: Christ Church Regatta, Torpids, and Summer Eights. In addition, there are higher standard :Oxford student sports clubs, university wide teams. Significant focus is given to annual List of British and Irish varsity matches, varsity matches played against Cambridge, the most famous of which is The Boat Race, watched by a TV audience of between five and ten million viewers. A Blue (university sport), blue is an award given to those who compete at the university team level in certain sports.

Music, drama, and other arts societies exist both at the collegiate level and as university-wide groups, such as the Oxford University Dramatic Society and the Oxford Revue. Most colleges have chapel choirs. The Oxford Imps, a comedy improvisation troupe, perform weekly at The Jericho Tavern during term time.

Private members' clubs for students include Vincent's Club (primarily for sportspeople) and The Gridiron Club (Oxford University), The Gridiron Club. A number of invitation-only student List of University of Oxford dining clubs, dining clubs also exist, including the Bullingdon Club.

The Oxford Union (distinct from Oxford University Student Union) is an independent debating society which hosts weekly debates and high-profile speakers. Party political groups include Oxford University Conservative Association and Oxford University Labour Club. Most academic areas have student societies of some form, for example the Oxford University Scientific Society, Scientific Society.

There are two weekly student newspapers: the independent ''Cherwell (newspaper), Cherwell'' and OUSU's ''The Oxford Student''. Other publications include the Isis magazine, ''Isis'' magazine, the satirical ''The Oxymoron, Oxymoron'', the graduate ''The Oxonian Review of Books, Oxonian Review'', the ''Oxford Political Review'', and the online only newspaper ''The Oxford Blue''. The Campus radio, student radio station is Oxide Radio.

Sport is played between college teams, in tournaments known as cuppers (the term is also used for some non-sporting competitions). In particular, much attention is given to the termly intercollegiate rowing regattas: Christ Church Regatta, Torpids, and Summer Eights. In addition, there are higher standard :Oxford student sports clubs, university wide teams. Significant focus is given to annual List of British and Irish varsity matches, varsity matches played against Cambridge, the most famous of which is The Boat Race, watched by a TV audience of between five and ten million viewers. A Blue (university sport), blue is an award given to those who compete at the university team level in certain sports.

Music, drama, and other arts societies exist both at the collegiate level and as university-wide groups, such as the Oxford University Dramatic Society and the Oxford Revue. Most colleges have chapel choirs. The Oxford Imps, a comedy improvisation troupe, perform weekly at The Jericho Tavern during term time.

Private members' clubs for students include Vincent's Club (primarily for sportspeople) and The Gridiron Club (Oxford University), The Gridiron Club. A number of invitation-only student List of University of Oxford dining clubs, dining clubs also exist, including the Bullingdon Club.

vol 7 excerpt

* * heavily illustrated * Catto, Jeremy (ed.), ''The History of the University of Oxford'', (Oxford UP, 1994). * Clark, Andrew (ed.), ''The colleges of Oxford: their history and traditions'', Methuen & C. (London, 1891). * Deslandes, Paul R. ''Oxbridge Men: British Masculinity & the Undergraduate Experience, 1850–1920'' (2005), 344pp * * Harrison, Brian Howard, ed. ''The History of the University of Oxford: Vol 8 The twentieth century'' (Oxford UP 1994). * Hibbert, Christopher, ''The Encyclopaedia of Oxford'', Macmillan Publishers, Macmillan (Basingstoke, 1988). * James Kelsey McConica, McConica, James. ''History of the University of Oxford. Vol. 3: The Collegiate University'' (1986), 775pp. * Mallet, Charles Edward. ''A history of the University of Oxford: The mediæval university and the colleges founded in the Middle Ages'' (2 vol 1924) * Midgley, Graham. ''University Life in Eighteenth-Century Oxford'' (1996) 192pp * Simcock, Anthony V. ''The Ashmolean Museum and Oxford Science, 1683–1983'' (Museum of the History of Science, 1984). * Sutherland, Lucy Stuart, Leslie G. Mitchell, and T. H. Aston, eds. ''The history of the University of Oxford'' (Clarendon, 1984).

v.1

* Snow, Peter, ''Oxford Observed'', John Murray (publishing house), John Murray (London, 1991).

'The University of Oxford', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3: The University of Oxford (1954), pp. 1–38

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Oxford, University Of University of Oxford, Russell Group 11th-century establishments in England, University of Oxford Educational institutions established in the 11th century Exempt charities, University of Oxford Organisations based in Oxford with royal patronage, University of Oxford Oxbridge, .Oxford, University of Universities UK Medieval European universities Ancient universities

collegiate

Collegiate may refer to:

* College

* Webster's Dictionary, a dictionary with editions referred to as a "Collegiate"

* ''Collegiate'' (1926 film), 1926 American silent film directed by Del Andrews

* ''Collegiate'' (1936 film), 1936 American musi ...

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are "the key sites of Knowledge production modes, knowledge production", along with "intergenerational ...

in Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world

The English-speaking world comprises the 88 countries and territories in which English language, English is an official, administrative, or cultural language. In the early 2000s, between one and two billion people spoke English, making it the ...

and the second-oldest continuously operating university globally. It expanded rapidly from 1167, when Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

prohibited English students from attending the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

. When disputes erupted between students and the Oxford townspeople, some Oxford academics fled northeast to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, where they established the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

in 1209. The two English ancient universities

The ancient universities are seven British and Irish medieval universities and early modern universities that were founded before 1600. Four of these are located in Scotland (Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, and University of St Andrews, St Andre ...

share many common features and are jointly referred to as ''Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of the University of Oxford, Universities of Oxford and University of Cambridge, Cambridge, the two oldest, wealthiest, and most prestigious universities in the United Kingdom. The term is used to refer to them collect ...

''.

The University of Oxford comprises 43 constituent colleges, consisting of 36 semi-autonomous colleges, four permanent private hall

A permanent private hall (PPH) in the University of Oxford is an educational institution within the University. There are four permanent private halls at Oxford, three of which admit undergraduates. They were founded by different Christian denomina ...

s and three societies (colleges that are departments of the university, without their own royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

). and a range of academic departments that are organised into four divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

. Each college is a self-governing institution within the university that controls its own membership and has its own internal structure and activities. All students are members of a college. Oxford does not have a main campus. Its buildings and facilities are scattered throughout the city centre and around the town. Undergraduate teaching

Undergraduate education is education conducted after secondary education and before postgraduate education, usually in a college or university. It typically includes all postsecondary programs up to the level of a bachelor's degree. For example, ...

at the university consists of lectures, small-group tutorials

In education, a tutorial is a method of transferring knowledge and may be used as a part of a learning process. More interactive and specific than a book or a lecture, a tutorial seeks to teach by example and supply the information to complete ...

at the colleges and halls, seminars, laboratory work and tutorials provided by the central university faculties and departments. Postgraduate teaching is provided in a predominantly centralised fashion.

Oxford operates the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street in Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University ...

, the world's oldest university museum

A university museum is a repository of collections run by a university, typically founded to aid teaching and research within the institution of higher learning. The Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford in England is an early example, or ...

; Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, the largest university press

A university press is an academic publishing house specializing in monographs and scholarly journals. They are often an integral component of a large research university. They publish work that has been reviewed by scholars in the field. They pro ...

in the world; and the largest academic library system nationwide. In the fiscal year ending 31 July 2024, the university had a total consolidated income of £3.05 billion, of which £778.9 million was from research grants and contracts. In 2024, Oxford ranked first nationally for undergraduate education

Undergraduate education is education conducted after secondary education and before postgraduate education, usually in a college or university. It typically includes all postsecondary programs up to the level of a bachelor's degree. For example, ...

.

Oxford has educated a wide range of notable alumni, including 31 prime ministers of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the principal minister of the crown of His Majesty's Government, and the head of the British Cabinet.

There is no specific date for when the office of prime minister first appeared, as the role w ...

and many heads of state and government around the world. 73 Nobel Prize laureates, 4 Fields Medalists

The Fields Medal is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians under 40 years of age at the International Congress of Mathematicians, International Congress of the International Mathematical Union (IMU), a meeting that takes place e ...

, and 6 Turing Award

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in the fi ...

winners have matriculated, worked, or held visiting fellowships at the University of Oxford. Its alumni have won 160 Olympic medal

An Olympic medal is awarded to successful competitors at one of the Olympic Games. There are three classes of medal to be won: gold medal, gold, silver medal, silver, and bronze medal, bronze, awarded to first, second, and third place, respect ...

s. Oxford is home to a number of scholarships, including the Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom. The scholarship is open to people from all backgrounds around the world.

Established in 1902, it is ...

, one of the oldest international graduate scholarship programmes in the world.

History

Founding

The University of Oxford's foundation date is unknown. In the 1300s, the historianRanulf Higden

Ranulf Higden or Higdon (–1363 or 1364) was an English chronicler and a Benedictine monk who wrote the ''Polychronicon'', a Late Medieval magnum opus. Higden resided at the monastery of St. Werburgh in Chester after taking his monastic vow a ...

wrote that the university was founded in the 9th century by Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

, but this story is apocryphal. It is known that teaching at Oxford existed in some form as early as 1096, but it is unclear when the university came into being. Scholar Theobald of Étampes

Theobald of Étampes (; ; born before 1080, died after 1120) was a medieval schoolmaster and theologian hostile to priestly celibacy. He is the first scholar known to have lectured at Oxford and is considered a forerunner of Oxford University.

Bio ...

lectured at Oxford in the early 1100s.

The university experienced rapid growth beginning in 1167, when English students were expelled from the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

by order of King Henry II, who, amid tensions with France and the Church, banned his subjects from studying abroad—prompting many scholars to return and establish a thriving academic community in Oxford. The historian Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales (; ; ; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taught in France and visited Rome several times, meeting the Pope. He ...

lectured to such scholars in 1188, and the first known foreign scholar, Emo of Friesland

Emo of Friesland (c. 1175–1237) was a Frisian scholar and abbot who probably came from the region of Groningen, and the earliest foreign student studying at Oxford University whose name has survived. He wrote a Latin chronicle, later expanded ...

, arrived in 1190. The head of the university had the title of chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

from at least 1201, and the masters were recognised as a ''universitas'' or corporation in 1231. The university was granted a royal charter in 1248 during the reign of King Henry III. After disputes between students and Oxford townsfolk in 1209, some academics fled from the violence to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, later forming the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

.

The students associated together on the basis of geographical origins, into two 'nations

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, territory, or societ ...

', representing the North (''northerners'' or ''Boreales'', who included the English people

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language in England, English language, a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language, and share a common ancestry, history, and culture. The Engl ...

from north of the River Trent

The Trent is the third Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, longest river in the United Kingdom. Its Source (river or stream), source is in Staffordshire, on the southern edge of Biddulph Moor. It flows through and drains the North Midlands ...

and the Scots) and the South (''southerners'' or ''Australes'', who included English people from south of the Trent, the Irish and the Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

). In later centuries, geographical origins continued to influence many students' affiliations when membership of a college

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further education institution, or a secondary sc ...

or hall

In architecture, a hall is a relatively large space enclosed by a roof and walls. In the Iron Age and the Early Middle Ages in northern Europe, a mead hall was where a lord and his retainers ate and also slept. Later in the Middle Ages, the gre ...

became customary at Oxford. Additionally, members of many religious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

s, including Dominicans

Dominicans () also known as Quisqueyans () are an ethnic group, ethno-nationality, national people, a people of shared ancestry and culture, who have ancestral roots in the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican ethnic group was born out of a fusio ...

, Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

s, Carmelites

The Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel (; abbreviated OCarm), known as the Carmelites or sometimes by synecdoche known simply as Carmel, is a mendicant order in the Catholic Church for both men and women. Histo ...

, and Augustinians

Augustinians are members of several religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written about 400 A.D. by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

, settled in Oxford in the mid-13th century, gained influence and maintained houses or halls for students. At about the same time, private benefactors established colleges as self-contained scholarly communities. Among the earliest such founders were William of Durham

William of Durham (died 1249) is said to have founded University College, Oxford, England.Univers ...

, who in 1249 endowed University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies f ...

, and John Balliol

John Balliol or John de Balliol ( – late 1314), known derisively as Toom Tabard (meaning 'empty coat'), was King of Scots from 1292 to 1296. Little is known of his early life. After the death of Margaret, Maid of Norway, Scotland entered an ...

, father of a future King of Scots

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British cons ...

; Balliol College

Balliol College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1263 by nobleman John I de Balliol, it has a claim to be the oldest college in Oxford and the English-speaking world.

With a governing body of a master and ar ...

bears his name. Another founder, Walter de Merton

Walter de Merton ( – 27 October 1277) was Lord Chancellor of England, Archdeacon of Bath, founder of Merton College, Oxford, and Bishop of Rochester. For the first two years of the reign of Edward I he was – in all but name – Regent of En ...

, a Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

of England and afterwards Bishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester, Kent, Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Rochester Cathedral, Cathedral Chur ...

, composed a series of regulations for college life; Merton College

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor ...

thereby became the model for such establishments at Oxford, as well as at Cambridge. Thereafter, an increasing number of students lived in colleges rather than in halls and religious houses.

In 1333–1334, an attempt by some dissatisfied Oxford scholars to found a new university at Stamford, Lincolnshire, was blocked by the universities of Oxford and Cambridge petitioning King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

. Thereafter, until the 1820s, no new universities were allowed to be founded in England, even in London; thus, Oxford and Cambridge had a duopoly, which was unusual in large western European countries.

Renaissance period

The new learning of the

The new learning of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

greatly influenced Oxford from the late 15th century onwards. Among university scholars of the period were William Grocyn

William Grocyn ( 14461519) was a humanist English scholar and friend of Erasmus.

Grocyn was a prominent educator born in Colerne, Wiltshire. Intended for the church, he attended Winchester College and later New College, Oxford. He held various po ...

, who contributed to the revival of Greek language

Greek (, ; , ) is an Indo-European languages, Indo-European language, constituting an independent Hellenic languages, Hellenic branch within the Indo-European language family. It is native to Greece, Cyprus, Italy (in Calabria and Salento), south ...

studies, and John Colet

John Colet (January 1467 – 16 September 1519) was an English Catholic priest and educational pioneer.

Colet was an English scholar, Renaissance humanist, theologian, member of the Worshipful Company of Mercers, and Dean of St Paul's Cathedr ...

, the noted biblical scholar

Biblical studies is the academic application of a set of diverse disciplines to the study of the Bible, with ''Bible'' referring to the books of the canonical Hebrew Bible in mainstream Jewish usage and the Christian Bible including the can ...

.

With the English Reformation

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops Oath_of_Supremacy, over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church ...

and the break of communion with the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, recusant

Recusancy (from ) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign of Elizabeth I, and temporarily repea ...

scholars from Oxford fled to continental Europe, settling especially at the University of Douai

The University of Douai (; ) was a historic university in Douai, France. With a medieval tradition of scholarly activity in the city, the university was established in 1559, and lectures began in 1562. It ceased operations from 1795 to 1808. In ...

. The method of teaching at Oxford was transformed from the medieval scholastic method

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and C ...

to Renaissance education, although institutions associated with the university experienced losses of land and revenues. As a centre of learning and scholarship, Oxford's reputation declined in the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

; enrolments fell and teaching was neglected.

In 1636, William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

, the chancellor and Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, codified the university's statutes. These, for the most part, remained its governing regulations until the mid-19th century. Laud was also responsible for the granting of a charter securing privileges for the University Press

A university press is an academic publishing house specializing in monographs and scholarly journals. They are often an integral component of a large research university. They publish work that has been reviewed by scholars in the field. They pro ...

, and he made notable contributions to the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

, the main library of the university. From the beginnings of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

as the established church until 1866, membership of the church was a requirement to graduate as a Bachelor of Arts, and Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

were only permitted to be promoted to Master of Arts starting in 1871. The university was a centre of the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

party during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

(1642–1651), while the town favoured the opposing Parliamentarian cause.

Wadham College

Wadham College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road. Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy Wadham, a ...

, founded in 1610, was the undergraduate college of Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

. He was part of a group of experimental scientists at Oxford in the 1650s, the Oxford Philosophical Club

The Oxford Philosophical Club, also referred to as the "Oxford Circle", was to a group of natural philosophers, mathematicians, physicians, virtuosi and dilettanti gathering around John Wilkins FRS (1614–1672) at Oxford University, Oxford in t ...

, which included Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

and Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

. This group, which has at times been linked with Boyle's " Invisible College", held regular meetings at Wadham under the guidance of the college's warden, John Wilkins

John Wilkins (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an English Anglican ministry, Anglican clergyman, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1 ...

, and the group formed the nucleus that went on to found the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

Modern period

Students

In 1827, a major review of the university's statutes, some over 500 years old, was conducted. Among the changes made at this time was the removal of the requirement that students swear an oath of enmity towards an Oxford townsmanHenry Symeonis

Henry Symeonis (fl. 1225–1264) was a wealthy Englishman from Oxford, who became the target of a "very strange" 550-year-long grudge at the University of Oxford. Until 1827, Oxford graduates had to swear an oath never to be reconciled with Hen ...

, who was found guilty of murdering an Oxford student in the mid-13th century.

Before reforms in the early 19th century, the curriculum at Oxford was notoriously narrow and impractical. Sir Spencer Walpole, a historian of contemporary Great Britain and a senior government official, had not attended any university. He said, "Few medical men, few solicitors, few persons intended for commerce or trade, ever dreamed of passing through a university career." He quoted the Oxford University Commissioners in 1852 stating: "The education imparted at Oxford was not such as to conduce to the advancement in life of many persons, except those intended for the ministry." Nevertheless, Walpole argued:

Of the students who matriculated in 1840, 65% were sons of professionals (34% were Anglican ministers). After graduation, 87% became professionals (59% as Anglican clergy). Out of the students who matriculated in 1870, 59% were sons of professionals (25% were Anglican ministers). After graduation, 87% became professionals (42% as Anglican clergy).

M. C. Curthoys and H. S. Jones argue that the rise of organised sport was one of the most remarkable and distinctive features of the history of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was carried over from the athleticism prevalent at the public schools such as Eton

Eton most commonly refers to Eton College, a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England.

Eton may also refer to:

Places

*Eton, Berkshire, a town in Berkshire, England

*Eton, Georgia, a town in the United States

*Éton, a commune in the Meuse depa ...

, Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

, Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

, and Harrow

Harrow may refer to:

Places

* Harrow, Victoria, Australia

* Harrow, Ontario, Canada

* The Harrow, County Wexford, a village in Ireland

* London Borough of Harrow, England

* Harrow, London, a town in London

* Harrow (UK Parliament constituency)

* ...

.

All students, regardless of their chosen area of study, were required to spend (at least) their first year preparing for a first-year examination that was heavily focused on classical language

According to the definition by George L. Hart, a classical language is any language with an independent literary tradition and a large body of ancient written literature.

Classical languages are usually extinct languages. Those that are still ...

s. Science students found this particularly burdensome and supported a separate science degree with Greek language

Greek (, ; , ) is an Indo-European languages, Indo-European language, constituting an independent Hellenic languages, Hellenic branch within the Indo-European language family. It is native to Greece, Cyprus, Italy (in Calabria and Salento), south ...

study removed from their required courses. This concept of a Bachelor of Science had been adopted at other European universities (London University

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degr ...

had implemented it in 1860) but an 1880 proposal at Oxford to replace the classical requirement with a modern language (like German or French) was unsuccessful. After considerable internal haggling over the structure of the arts curriculum, in 1886 the "natural science preliminary" was recognised as a qualifying part of the first year examination.

At the start of 1914, the university housed about 3,000 undergraduates and around 100 postgraduate students. During the First World War, many undergraduates and fellows joined the armed forces. By 1918 nearly all fellows were serving in uniform, and the student population in residence was reduced to 12% of the pre-war total. The University Roll of Service records that, in total, 14,792 members of the university served in the war, with 2,716 (18.36%) killed. Not all the members of the university who served in the Great War fought with the Allies; there is a memorial to members of New College who served in the German armed forces, bearing the inscription, 'In memory of the men of this college who coming from a foreign land entered into the inheritance of this place and returning fought and died for their country in the war 1914–1918'. During the war years the university buildings became hospitals, cadet schools and military training camps.

Reforms

Two parliamentary commissions in 1852 issued recommendations for Oxford and Cambridge.Archibald Campbell Tait

Archibald Campbell Tait (21 December 18113 December 1882) is an Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England and theologian. He was the first Scottish Archbishop of Canterbury and thus, head of the Church of England.

Life

Tait was born ...

, a former headmaster of Rugby School, was a key member of the Oxford Commission; he wanted Oxford to follow the German and Scottish model in which the professorship was paramount. The commission's report envisioned a centralised university run predominantly by professors and faculties, with a much stronger emphasis on research. The professional staff should be strengthened and better paid. For students, restrictions on entry should be dropped, and more opportunities given to poorer families. It called for an expansion of the curriculum, with honours to be awarded in many new fields. Undergraduate scholarships should be open to all Britons. Graduate fellowships should be opened up to all members of the university. It recommended that fellows be released from an obligation for ordination. Students were to be allowed to save money by boarding in the city, instead of in one of the colleges.

The system of separate honour schools for different subjects began in 1802, with Mathematics and Literae Humaniores. Schools of "Natural Sciences" and "Law, and Modern History" were added in 1853. By 1872, the last of these had split into "Jurisprudence" and "Modern History". Theology became the sixth honour school. In addition to these B.A. Honours degrees, the postgraduate Bachelor of Civil Law (B.C.L.) was, and still is, offered.

The mid-19th century saw the impact of the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a theological movement of high-church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the Un ...

(1833–1845), led, among others, by the future Cardinal John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English Catholic theologian, academic, philosopher, historian, writer, and poet. He was previously an Anglican priest and after his conversion became a cardinal. He was an ...

. Administrative reforms during the 19th century included the replacement of oral examinations with written entrance tests, greater tolerance for religious dissent, and the establishment of four women's colleges. Privy Council decisions in the 20th century - the abolition of compulsory daily worship, dissociation of the Regius Professorship of Hebrew from clerical status, diversion of colleges' theological bequests to other purposes - loosened the link with traditional belief and practice. Furthermore, although the university's emphasis had historically been on classical knowledge, its curriculum expanded during the 19th century to include scientific and medical studies.

The postgraduate degrees of Bachelor of Science and Bachelor of Letters (renamed Master of Science

A Master of Science (; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree. In contrast to the Master of Arts degree, the Master of Science degree is typically granted for studies in sciences, engineering and medici ...

and Master of Letters

A Master of Letters degree (MLitt or LittM; Latin ' or ') is a postgraduate degree.

Ireland

Trinity College Dublin and Maynooth University offer MLitt degrees. Trinity has offered them the longest, owing largely to its tradition as Ireland's ...

in the 1970s) were introduced in 1895, and the university began to award doctorates for research in 1900 with the Doctor of Letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or '), also termed Doctor of Literature in some countries, is a terminal degree in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. In the United States, at universities such as Drew University, the degree ...

and Doctor of Science

A Doctor of Science (; most commonly abbreviated DSc or ScD) is a science doctorate awarded in a number of countries throughout the world.

Africa

Algeria and Morocco

In Algeria, Morocco, Libya and Tunisia, all universities accredited by the s ...

degrees. Oxford was the first British university to institute a Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of Postgraduate education, graduate study and original resear ...

degree (abbreviated DPhil) in 1917; it was first awarded in 1919 to Lakshman Sarup of Balliol College.

Women's education

The university passed a statute in 1875 allowing examinations for women at at a level approximately equivalent to undergraduate studies; for a brief period in the early 1900s, this allowed the "steamboat ladies

"Steamboat ladies" was an informal nickname given to a number of female students (estimated at around 720 graduates) at the women's colleges of the Universities of both Oxford and Cambridge, who were awarded University of Dublin degrees at Trini ...

" to receive ''ad eundem

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a product or service. Advertising aims to present a product or service in terms of utility, advantages, and qualities of interest to consumers. It is typically used ...

'' degrees from the University of Dublin

The University of Dublin (), corporately named as The Chancellor, Doctors and Masters of the University of Dublin, is a research university located in Dublin, Republic of Ireland. It is the degree-awarding body for Trinity College Dublin, whi ...

. In June 1878, the Association for the Education of Women

The Association for the Education of Women or Association for Promoting the Higher Education of Women in Oxford (AEW) was formed in 1878 to promote the education of women at the University of Oxford. It provided lectures and tutorials for stud ...

(AEW) was formed, aiming for the eventual creation of a college for women in Oxford. Some of the more prominent members of the association were George Granville Bradley

George Granville Bradley (11 December 1821 – 13 March 1903) was an English divine, scholar, and schoolteacher, who was Dean of Westminster (1881–1902).

Life

Bradley was a son of the preacher Charles Bradley (1789–1871), vicar of Glasb ...

, T. H. Green

Thomas Hill Green (7 April 183626 March 1882), known as T. H. Green, was an English philosopher, political Radicalism (historical), radical and Temperance movement, temperance reformer, and a member of the British idealism movement. Like ...

and Edward Stuart Talbot

Edward Stuart Talbot (19 February 1844 – 30 January 1934) was an Anglican bishop in the Church of England and the first Warden of Keble College, Oxford. He was successively the Bishop of Rochester, the Bishop of Southwark and the Bishop of W ...

. Talbot insisted on a specifically Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

institution, which was unacceptable to most of the other members. The two parties eventually split, and Talbot's group founded Lady Margaret Hall

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, located on a bank of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The college is more formally known under ...

in 1878, while T. H. Green founded the non-denominational Somerville College

Somerville College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. It began admitting men in 1994. The college's liberal tone derives from its f ...

in 1879. Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville opened their doors to their first 21 students (12 at Somerville, 9 at Lady Margaret Hall) in 1879, who attended lectures in rooms above an Oxford baker's shop. There were also 25 women students living at home or with friends in 1879, a group which evolved into the Society of Oxford Home-Students and in 1952 into St Anne's College.

These first three societies for women were followed by St Hugh's (1886) and St Hilda's (1893). All of these colleges later became coeducational, starting with Lady Margaret Hall

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, located on a bank of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The college is more formally known under ...

and St Anne's in 1979, and finishing with St Hilda's, which began to accept male students in 2008. In the early 20th century, Oxford and Cambridge were widely perceived to be bastions of male privilege

Male privilege is the system of advantages or rights that are available to men on the basis of their sex. A man's access to these benefits may vary depending on how closely they match their society's ideal masculine norm.

Academic studies ...

; however, the integration of women into Oxford moved forward during the First World War. In 1916 women were admitted as medical students on a par with men, and in 1917 the university accepted financial responsibility for women's examinations.

On 7 October 1920 women became eligible for admission as full members of the university and were given the right to take degrees. In 1927 the university's dons created a quota that limited the number of female students to a quarter that of men, a ruling which was not abolished until 1957. Additionally, during this period Oxford colleges were single sex, so the number of women was also limited by the capacity of the women's colleges to admit students. It was not until 1959 that the women's colleges were given full collegiate status.

In 1974, Brasenose, Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

, Wadham, Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a Ford (crossing), ford on ...

and St Catherine's became the first formerly all-male colleges to admit women. The majority of men's colleges accepted their first female students in 1979, with Christ Church following in 1980, and Oriel becoming the last men's college to admit women in 1985. Most of Oxford's graduate colleges were founded as coeducational establishments in the 20th century, with the exception of St Antony's, which was founded as a men's college in 1950 and began to accept women only in 1962. By 1988, 40% of undergraduates at Oxford were female; in 2016, 45% of the student population, and 47% of undergraduate students, were female.

In June 2017, Oxford announced that starting in the 2018 academic year, history students may choose to sit a take-home exam in some courses, with the intention that this will equalise rates of firsts awarded to women and men at Oxford. That same summer, maths and computer science tests were extended by 15 minutes, in a bid to see if female student scores would improve.

The detective novel ''Gaudy Night

''Gaudy Night'' (1935) is a mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the tenth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey, and the third including Harriet Vane.

The dons of Harriet Vane's ''alma mater'', the all-female Shrewsbury College, Oxford (based on Say ...

'' by Dorothy L. Sayers

Dorothy Leigh Sayers ( ; 13 June 1893 – 17 December 1957) was an English crime novelist, playwright, translator and critic.

Born in Oxford, Sayers was brought up in rural East Anglia and educated at Godolphin School in Salisbury and Somerv ...

, one of the first women to gain an academic degree from Oxford, is largely set in the all-female Shrewsbury College, Oxford (based on Sayers' own Somerville College

Somerville College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. It began admitting men in 1994. The college's liberal tone derives from its f ...

), and the issue of women's education is central to its plot. Social historian and Somerville College alumna Jane Robinson's book ''Bluestockings: A Remarkable History of the First Women to Fight for an Education'' gives a very detailed and immersive account of this history.

Buildings and sites

Map

Main sites

Radcliffe Observatory Quarter

The Radcliffe Observatory Quarter (ROQ) is a major University of Oxford development project in Oxford, England, in the estate of the old Radcliffe Infirmary hospital.

The site, covering 10 acres (3.7 hectares) is in central north Oxford. It is ...

in the northwest of the city.

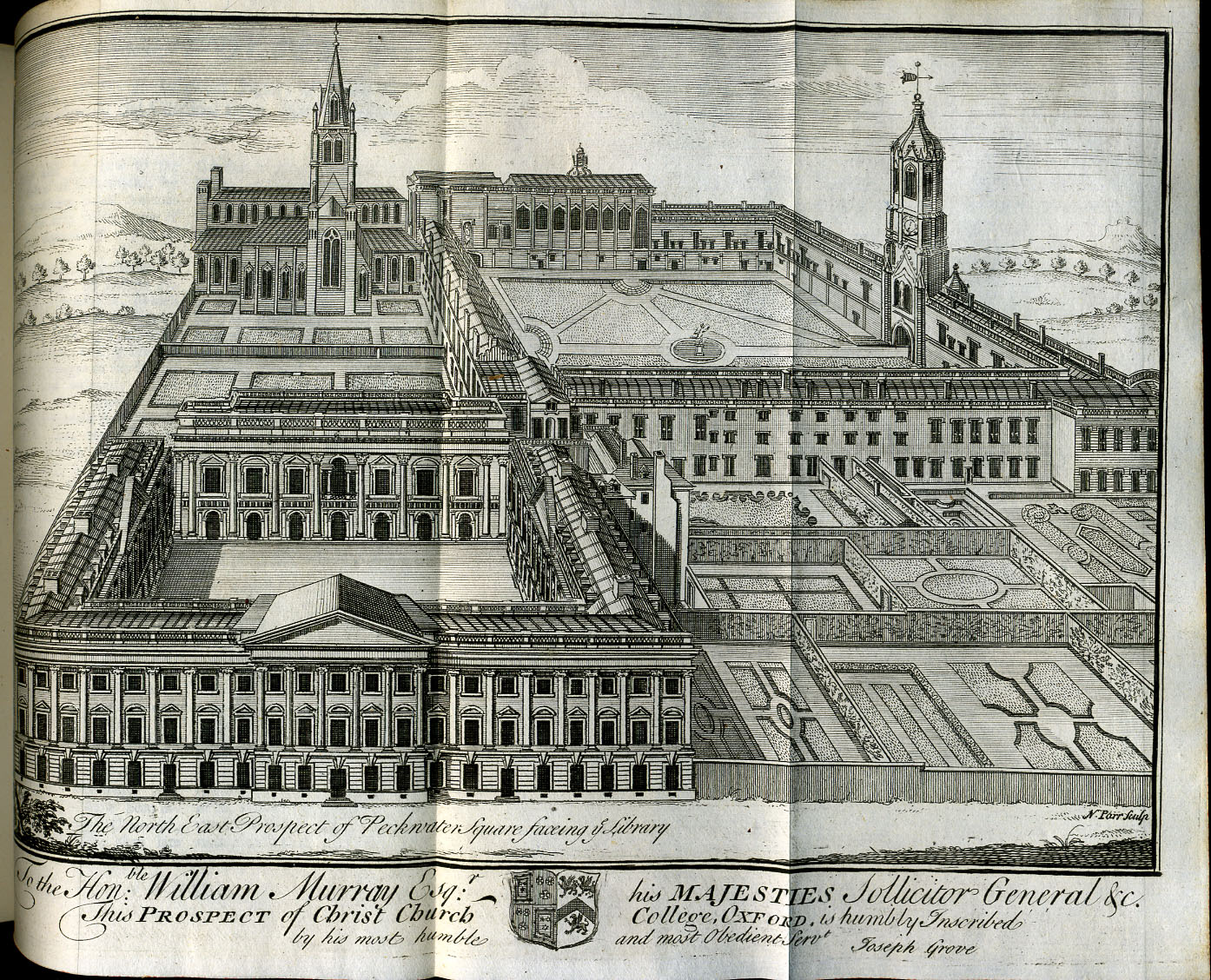

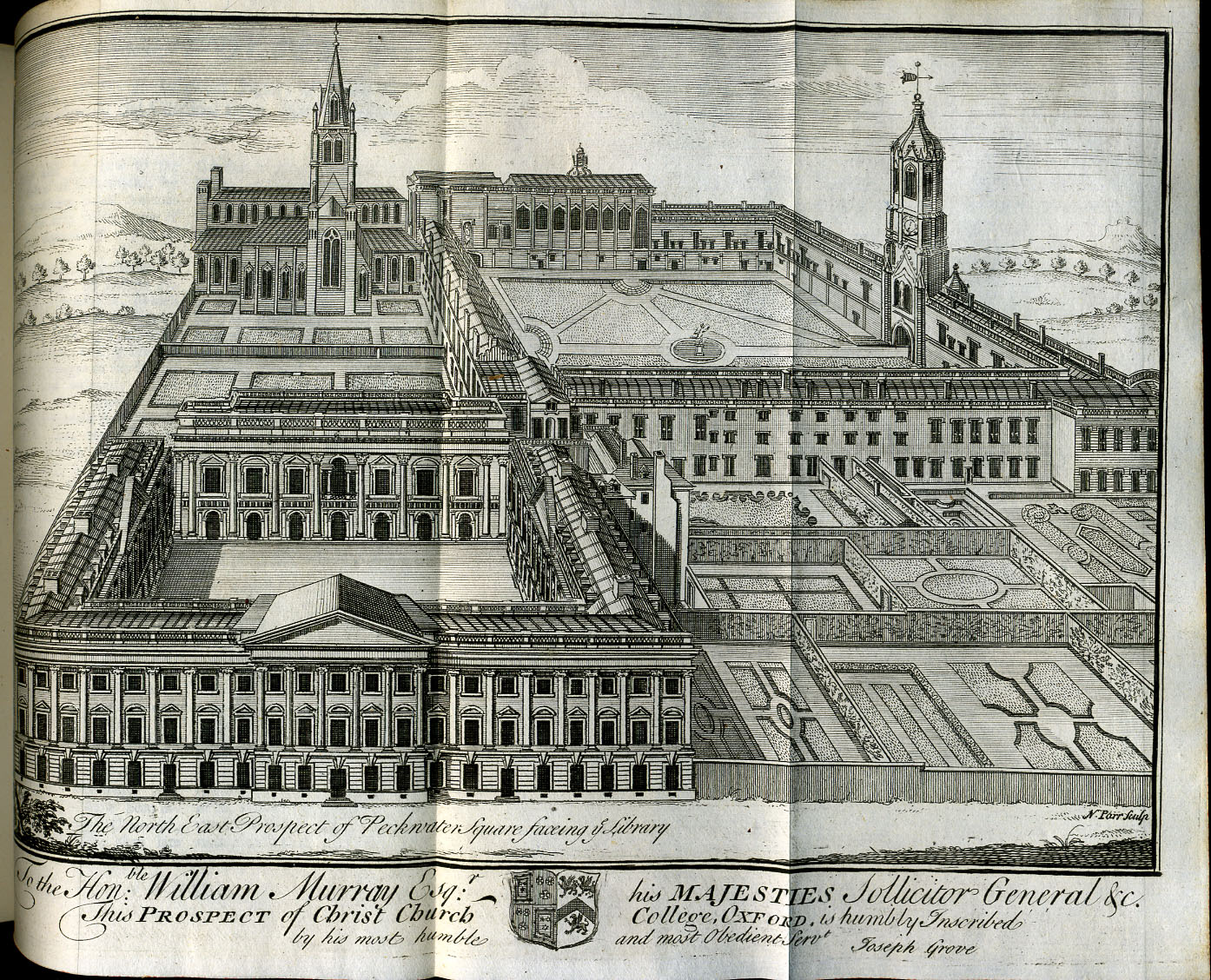

Iconic university buildings include the Radcliffe Camera

The Radcliffe Camera (colloquially known as the "Rad Cam" or "The Camera"; from Latin , meaning 'room') is a building of the University of Oxford, England, designed by James Gibbs in a Baroque style and built in 1737–49 to house the Radclif ...

, the Sheldonian Theatre

The Sheldonian Theatre, in the centre of Oxford, England, was built from 1664 to 1669 after a design by Christopher Wren for the University of Oxford. The building is named after Gilbert Sheldon, List of Wardens of All Souls College, Oxford, Wa ...

used for music concerts, lectures, and university ceremonies, and the Examination Schools

The Examination Schools of the University of Oxford are located at 75–81 High Street, Oxford, High Street, Oxford, England. The building was designed by Thomas Graham Jackson, Sir Thomas Jackson (1835–1924), who also designed several other U ...

, where examinations and some lectures take place. The University Church of St Mary the Virgin

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin (St Mary's or SMV for short) is an Anglican church in Oxford situated on the north side of the High Street. It is the centre from which the University of Oxford grew and its parish consists almost excl ...

was used for university ceremonies before the construction of the Sheldonian.

In 2012–2013, the university built the controversial one-hectare (400 m × 25 m) Castle Mill

Castle Mill is a graduate housing complex of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England.

Overview

Castle Mill is located north of Oxford railway station along Roger Dudman Way, just to the west of the railway tracks and the Oxford Down ...

development of 4–5-storey blocks of student flats overlooking Cripley Meadow

Cripley Meadow lies between the Castle Mill Stream, a backwater of the River Thames, and the Cotswold Line railway to the east, and Fiddler's Island, on the main branch of the Thames to the west, in Oxford, England. It is to the south of the be ...

and the historic Port Meadow

Port Meadow is a large meadow of open common land beside the River Thames to the north and west of Oxford, England.

Overview

The meadow is an ancient area of grazing land, still used for horses and cattle, and according to legend has never bee ...

, blocking views of the spires in the city centre. The development has been likened to building a "skyscraper beside Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric Megalith, megalithic structure on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, to ...

".

Parks

TheUniversity Parks

The Oxford University Parks, commonly referred to locally as the University Parks, or just The Parks, is a large parkland area slightly northeast of the city centre in Oxford, England. The park is bounded to the east by the River Cherwell, tho ...

are a 70-acre (28 ha) parkland area in the northeast of the city, near Keble College

Keble College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Its main buildings are on Parks Road, opposite the University Museum and the University Parks. The college is bordered to the north by Keble Road, to ...

, Somerville College

Somerville College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It was founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, one of its first two women's colleges. It began admitting men in 1994. The college's liberal tone derives from its f ...

and Lady Margaret Hall

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England, located on a bank of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks. The college is more formally known under ...

. It is open to the public during daylight hours. There are also various college-owned open spaces open to the public, including Bagley Wood

Bagley Wood is a wood in the parish of Kennington, Oxfordshire, Kennington, in the Vale of White Horse district, between Oxford and Abingdon, Oxfordshire, Abingdon in Oxfordshire, England (in Berkshire until 1974). It is traversed from north to ...

and most notably Christ Church Meadow.

The Botanic Garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens. is ...

on the High Street

High Street is a common street name for the primary business street of a city, town, or village, especially in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. It implies that it is the focal point for business, especially shopping. It is also a metonym fo ...

is the oldest botanic garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens. is ...

in the UK. It contains over 8,000 different plant species on . It is one of the most diverse yet compact major collections of plants in the world and includes representatives of over 90% of the higher plant families. The Harcourt Arboretum

Harcourt Arboretum is an arboretum owned and run by the University of Oxford. It is a satellite of the university's botanic garden in the city of Oxford, England. The arboretum itself is located south of Oxford on the A4074 road, near the vill ...

is a site south of the city that includes native woodland and of meadow. The Wytham Woods

Wytham Woods is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest north-west of Oxford in Oxfordshire. It is a Nature Conservation Review site.

Habitats in this site, which formerly belonged to Abingdon Abbey, include ancient woodland and limest ...

are owned by the university and used for research in zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

and climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

.

Organisation

Colleges arrange the tutorial teaching for their undergraduates, and the members of an academic department are spread around many colleges. Though certain colleges do have subject alignments (e.g.,Nuffield College

Nuffield College () is one of the Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. It is a graduate college specialising in the social sciences, particularly economics, politics and sociology. N ...

as a centre for the social sciences), these are exceptions, and most colleges will have a diverse community of students and academics representing a wide range of disciplines. Facilities such as libraries are provided on all these levels: by the central university (the Bodleian

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

), by the departments (individual departmental libraries, such as the English Faculty Library), and by colleges (each of which maintains a multi-discipline library for the use of its members).

Central governance

The university's formal head is the

The university's formal head is the chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

, with Lord Hague of Richmond expected to be inaugurated in early 2025 although, as at most British universities, the chancellor is a titular figurehead and is not involved with the day-to-day running of the university. The chancellor is elected by the members of convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a specia ...

, a body comprising all graduates of the university, and may hold office until death.

The vice-chancellor

A vice-chancellor (commonly called a VC) serves as the chief executive of a university in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, other Commonwealth of Nati ...

, currently Irene Tracey

Irene Mary Carmel Tracey (born 30 October 1966) is a British neuroscientist who is Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford and former Warden of Merton College, Oxford. She is also Professor of Anaesthetic Neuroscience in the Nuffield Departmen ...

, is the ''de facto'' head of the university. There are five pro-vice-chancellors with specific responsibilities.

Two university proctors

Proctor's Theatre (officially stylized as Proctors since 2007; however, the marquee retains the apostrophe) is a theatre and former vaudeville house located in Schenectady, New York, United States. Many famous artists have performed there, includ ...

, elected annually on a rotating basis from any two of the colleges, are the internal ombudsmen who make sure that the university and its members adhere to its statutes. This role incorporates student discipline and complaints, as well as oversight of the university's proceedings. The university's professors are collectively referred to as the Statutory Professors of the University of Oxford

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

. They are particularly influential in the running of the university's graduate programmes. Examples of statutory professors are the Chichele Professorship

The Chichele Professorships are statutory professorships at the University of Oxford named in honour of Henry Chichele (also spelt Chicheley or Checheley, although the spelling of the academic position is consistently "Chichele"), an Archbishop of ...

s and the Drummond Professor of Political Economy.

Oxford is a "public university" in that it receives some public money from the government, but it is a "private university" in that it is entirely self-governing and, in theory, could choose to become entirely private by rejecting public funds.

Colleges

To be a member of the university, all students, and most academic staff, must also be a member of a college or hall. There are thirty-ninecolleges of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford has 36 colleges within universities in the United Kingdom#Traditional collegiate universities, colleges, three societies, and four permanent private halls (PPHs) of religious foundation. The colleges and PPHs are autonom ...

and four permanent private hall

A permanent private hall (PPH) in the University of Oxford is an educational institution within the University. There are four permanent private halls at Oxford, three of which admit undergraduates. They were founded by different Christian denomina ...

s (PPHs), each controlling its membership and with its own internal structure and activities. Not all colleges offer all courses, but they generally cover a broad range of subjects.

The 39 colleges are:

‡ These three have no royal charter, and are officially departments of the university rather than independent colleges.

The permanent private halls were founded by different Christian denominations. One difference between a college and a PPH is that whereas colleges are governed by the fellows Fellows may refer to Fellow, in plural form.

Fellows or Fellowes may also refer to:

Places

*Fellows, California, USA

*Fellows, Wisconsin, ghost town, USA

Other uses

* Fellowes, Inc., manufacturer of workspace products

*Fellows, a partner in the f ...

of the college, the governance of a PPH resides, at least in part, with the corresponding Christian denomination. The four PPHs are:

*

*

*

*

The PPHs and colleges join as the Conference of Colleges, which represents their common concerns, to discuss matters of shared interest and to act collectively when necessary, such as in dealings with the central university. The Conference of Colleges was established as a recommendation of the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

Commission in 1965.

Teaching members of the colleges (i.e. fellows and tutors) are collectively and familiarly known as dons, although the term is rarely used by the university itself. In addition to residential and dining facilities, the colleges provide social, cultural, and recreational activities for their members. Colleges have responsibility for admitting undergraduates and organising their tuition; for graduates, this responsibility falls upon the departments.

Finances

The combined endowment figure of £8.708 billion makes Oxford hold the largest endowment of any university in the UK. The college figure does not reflect all the assets held by the colleges as their accounts do not include the cost or value of many of their main sites or heritage assets such as works of art or libraries.

The central University's endowment, along with some of the colleges', is managed by the university's wholly-owned endowment management office, Oxford University Endowment Management, formed in 2007. The university used to maintain substantial investments in fossil fuel companies. However, in April 2020, the university committed to divest from direct investments in fossil fuel companies and to require indirect investments in fossil fuel companies be subjected to the Oxford Martin Principles.

The university was one of the first in the UK to raise money through a major public fundraising campaign, the

The combined endowment figure of £8.708 billion makes Oxford hold the largest endowment of any university in the UK. The college figure does not reflect all the assets held by the colleges as their accounts do not include the cost or value of many of their main sites or heritage assets such as works of art or libraries.

The central University's endowment, along with some of the colleges', is managed by the university's wholly-owned endowment management office, Oxford University Endowment Management, formed in 2007. The university used to maintain substantial investments in fossil fuel companies. However, in April 2020, the university committed to divest from direct investments in fossil fuel companies and to require indirect investments in fossil fuel companies be subjected to the Oxford Martin Principles.

The university was one of the first in the UK to raise money through a major public fundraising campaign, the Campaign for Oxford

The University of Oxford has been running a series of fundraising appeals since 1988, under the name of the Campaign for Oxford. These appeals aim to raise funds for various academic and research purposes at the university, such as scholarsh ...

. The current campaign, its second, was launched in May 2008 and is entitled "Oxford Thinking – The Campaign for the University of Oxford". This is looking to support three areas: academic posts and programmes, student support, and buildings and infrastructure; having passed its original target of £1.25 billion in March 2012, the target was raised to £3 billion.

Funding criticisms

The university has faced criticism for some of its sources of donations and funding. In 2017, attention was drawn to historical donations includingAll Souls College

All Souls College (official name: The College of All Souls of the Faithful Departed, of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full me ...

receiving £10,000 from slave trader Christopher Codrington

Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Codrington ( – 7 April 1710) was an English Army officer, planter and colonial administrator who served as governor of the Leeward Islands from 1699 to 1704. Born on Barbados into the planter class, he inheri ...

in 1710, and Oriel College receiving £100,000 from the will of the imperialist Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

in 1902. In 1996 a donation of £20 million was received from Wafic Saïd

Wafic Rida Saïd () (born 21 December 1939) is a Syrian-Saudi-Canadian businessman, financier, and philanthropist who has resided for many years in Monaco.David Pallister, 'The man of substance in the shadows', ''The Guardian'', London, 22 May ...

who was involved in the Al-Yammah arms deal, and taking £150 million from the US billionaire businessman Stephen A. Schwarzman

Stephen Allen Schwarzman (born February 14, 1947) is an American businessman. He is the chairman and CEO of the Blackstone Group, a global private equity firm he established in 1985 with Peter G. Peterson. Schwarzman was chairman of President Do ...

in 2019. The university has defended its decisions saying it "takes legal, ethical and reputational issues into consideration".

The university also faced criticism, as noted above, over its decision to accept donations from fossil fuel companies having received £21.8 million from the fossil fuel industry between 2010 and 2015, £18.8 million between 2015 and 2020 and £1.6 million between 2020 and 2021.

The university accepted £6 million from The Alexander Mosley Charitable Trust in 2021. Former racing driver Max Mosley