Teschen Conflict on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Trans-Olza (, ; , ''Záolší''; ), also known as Trans-Olza Silesia (), is a territory in the

After the fall of Great Moravia in 907 the area could have been under the influence of

After the fall of Great Moravia in 907 the area could have been under the influence of  Up to the mid-19th century members of the local Slav population did not identify themselves as members of larger ethnolinguistic entities. In Cieszyn Silesia (as in all West Slavic borderlands) various territorial identities pre-dated ethnic and national identity. Consciousness of membership within a greater Polish or Czech nation spread slowly in Silesia.

From 1848 to the end of the 19th century, local Polish and Czech people co-operated, united against the Germanizing tendencies of the

Up to the mid-19th century members of the local Slav population did not identify themselves as members of larger ethnolinguistic entities. In Cieszyn Silesia (as in all West Slavic borderlands) various territorial identities pre-dated ethnic and national identity. Consciousness of membership within a greater Polish or Czech nation spread slowly in Silesia.

From 1848 to the end of the 19th century, local Polish and Czech people co-operated, united against the Germanizing tendencies of the

Cieszyn Silesia was claimed by both Poland and Czechoslovakia: the Polish ''Rada Narodowa Księstwa Cieszyńskiego'' made its claim in its declaration "Ludu śląski!" of 30 October 1918, and the Czech ''Zemský národní výbor pro Slezsko'' did so in its declaration of 1 November 1918.Gawrecká 2004, 21. On 31 October 1918, at the end of World War I and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the majority of the area was taken over by local Polish authorities supported by armed forces. An interim agreement from 2 November 1918 reflected the inability of the two national councils to come to final

Cieszyn Silesia was claimed by both Poland and Czechoslovakia: the Polish ''Rada Narodowa Księstwa Cieszyńskiego'' made its claim in its declaration "Ludu śląski!" of 30 October 1918, and the Czech ''Zemský národní výbor pro Slezsko'' did so in its declaration of 1 November 1918.Gawrecká 2004, 21. On 31 October 1918, at the end of World War I and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the majority of the area was taken over by local Polish authorities supported by armed forces. An interim agreement from 2 November 1918 reflected the inability of the two national councils to come to final

Historian Richard M. Watt writes, "On 5 November 1918, the Poles and the Czechs in the region disarmed the Austrian garrison (...) The Poles took over the areas that appeared to be theirs, just as the Czechs had assumed administration of theirs. Nobody objected to this friendly arrangement (...) Then came second thoughts in

Historian Richard M. Watt writes, "On 5 November 1918, the Poles and the Czechs in the region disarmed the Austrian garrison (...) The Poles took over the areas that appeared to be theirs, just as the Czechs had assumed administration of theirs. Nobody objected to this friendly arrangement (...) Then came second thoughts in  Watt argues that Beneš strategically waited for Poland's moment of weakness, and moved in during the Polish-Soviet War crisis in July 1920. As Watt writes, "Over the dinner table, Beneš convinced the British and French that the plebiscite should not be held and that the Allies should simply impose their own decision in the Cieszyn matter. More than that, Beneš persuaded the French and the British to draw a frontier line that gave Czechoslovakia most of the territory of Cieszyn, the vital railroad and all the important coal fields. With this frontier, 139,000 Poles were to be left in Czech territory, whereas only 2,000 Czechs were left on the Polish side".

"The next morning Beneš visited the Polish delegation at Spa. By giving the impression that the Czechs would accept a settlement favorable to the Poles without a plebiscite, Beneš got the Poles to sign an agreement that Poland would abide by any Allied decision regarding Cieszyn. The Poles, of course, had no way of knowing that Beneš had already persuaded the Allies to make a decision on Cieszyn. After a brief interval, to make it appear that due deliberation had taken place, the Allied Council of Ambassadors in Paris imposed its 'decision'. Only then did it dawn on the Poles that at Spa they had signed a blank check. To them, Beneš' stunning triumph was not diplomacy, it was a swindle (...) As Polish Prime Minister

Watt argues that Beneš strategically waited for Poland's moment of weakness, and moved in during the Polish-Soviet War crisis in July 1920. As Watt writes, "Over the dinner table, Beneš convinced the British and French that the plebiscite should not be held and that the Allies should simply impose their own decision in the Cieszyn matter. More than that, Beneš persuaded the French and the British to draw a frontier line that gave Czechoslovakia most of the territory of Cieszyn, the vital railroad and all the important coal fields. With this frontier, 139,000 Poles were to be left in Czech territory, whereas only 2,000 Czechs were left on the Polish side".

"The next morning Beneš visited the Polish delegation at Spa. By giving the impression that the Czechs would accept a settlement favorable to the Poles without a plebiscite, Beneš got the Poles to sign an agreement that Poland would abide by any Allied decision regarding Cieszyn. The Poles, of course, had no way of knowing that Beneš had already persuaded the Allies to make a decision on Cieszyn. After a brief interval, to make it appear that due deliberation had taken place, the Allied Council of Ambassadors in Paris imposed its 'decision'. Only then did it dawn on the Poles that at Spa they had signed a blank check. To them, Beneš' stunning triumph was not diplomacy, it was a swindle (...) As Polish Prime Minister

The local Polish population felt that Warsaw had betrayed them and they were not satisfied with the division of Cieszyn Silesia. About 12,000 to 14,000 Poles were forced to leave to Poland.Gabal 1999, 120. It is not quite clear how many Poles were in Trans-Olza in Czechoslovakia. Estimates (depending mainly whether the

The local Polish population felt that Warsaw had betrayed them and they were not satisfied with the division of Cieszyn Silesia. About 12,000 to 14,000 Poles were forced to leave to Poland.Gabal 1999, 120. It is not quite clear how many Poles were in Trans-Olza in Czechoslovakia. Estimates (depending mainly whether the

Within the region originally demanded from Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in 1938 was the important railway junction city of

Within the region originally demanded from Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in 1938 was the important railway junction city of

Immediately after World War II, Trans-Olza was returned to Czechoslovakia within its 1920 borders, although local Poles had hoped it would again be given to Poland. Most Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovaks of German ethnicity were expelled, and the local Polish population again suffered discrimination, as many Czechs blamed them for the discrimination by the Polish authorities in 1938–1939. Polish organizations were banned, and the Czechoslovak authorities carried out many arrests and dismissed many Poles from work. The situation had somewhat improved when the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took power in February 1948. Polish property deprived by the German occupants during the war was never returned.

As to the Catholic parishes in Trans-Olza pertaining to the Archdiocese of Breslau Archbishop Bertram, then residing in the episcopal Jánský vrch castle in Czechoslovak Javorník (Jeseník District), Javorník, appointed František Onderek (1888–1962) as ''vicar general for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' on 21 June 1945. In July 1946 Pope Pius XII elevated Onderek to ''Apostolic Administrator for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' (colloquially: Apostolic Administration of Český Těšín; ), seated in

Immediately after World War II, Trans-Olza was returned to Czechoslovakia within its 1920 borders, although local Poles had hoped it would again be given to Poland. Most Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovaks of German ethnicity were expelled, and the local Polish population again suffered discrimination, as many Czechs blamed them for the discrimination by the Polish authorities in 1938–1939. Polish organizations were banned, and the Czechoslovak authorities carried out many arrests and dismissed many Poles from work. The situation had somewhat improved when the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took power in February 1948. Polish property deprived by the German occupants during the war was never returned.

As to the Catholic parishes in Trans-Olza pertaining to the Archdiocese of Breslau Archbishop Bertram, then residing in the episcopal Jánský vrch castle in Czechoslovak Javorník (Jeseník District), Javorník, appointed František Onderek (1888–1962) as ''vicar general for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' on 21 June 1945. In July 1946 Pope Pius XII elevated Onderek to ''Apostolic Administrator for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' (colloquially: Apostolic Administration of Český Těšín; ), seated in

The entry of both the Czech Republic and

The entry of both the Czech Republic and

Jarosław Jot-Drużycki: Poles living in Zaolzie identify themselves better with Czechs

. ''European Foundation of Human Rights.'' 3 September 2014.

Documents and photographs about the situation in Zaolzie in 1938

{{good article Historical regions Cieszyn Silesia Czech Republic–Poland border Czechoslovakia–Poland border Czechoslovakia–Poland relations Czechoslovakia–Germany relations Germany–Poland relations (1918–1939) History of Czech Silesia Moravian-Silesian Region Polish minority in Trans-Olza Territorial disputes of Czechoslovakia Territorial disputes of Poland Historical regions in the Czech Republic Interwar Czechoslovakia Former disputed land areas

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

which was disputed between Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

during the Interwar Period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

. Its name comes from the Olza River.

The history of the Trans-Olza region began in 1918 when, after the collapse of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, the newly-established Czechoslovakia claimed the area, which was mainly inhabited by Poles. Poland maintained control over the region and began to hold elections, to which Czechoslovakia responded by invading and annexing the territory in January 1919.

The area as it is known today was created in 1920, when Cieszyn Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia, Těšín Silesia or Teschen Silesia ( ; or ; or ) is a historical region in south-eastern Silesia, centered on the towns of Cieszyn and Český Těšín and bisected by the Olza River. Since 1920 it has been divided betwe ...

was divided between the two countries during the Spa Conference. Trans-Olza forms the eastern part of the Czech portion of Cieszyn Silesia. The division again did not satisfy any side, and persisting conflict over the region led to its annexation by Poland in October 1938, following the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. After the German-Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, the area became a part of Nazi Germany until 1945. After the war, the 1920 borders were restored.

Historically, the largest specified ethnic group inhabiting this area were Poles. Under Austrian rule, Cieszyn Silesia was initially divided into three (Bielitz

Bielsko (, ) was until 1950 an independent town situated in Cieszyn Silesia, Poland. In 1951 it was joined with Biała Krakowska to form the new town of Bielsko-Biała. Bielsko constitutes the western part of that town.

Bielsko was founded by ...

, Friedek and Teschen), and later into four districts (plus Freistadt). One of them, Frýdek, had a mostly Czech population, the other three were mostly inhabited by Poles. During the 19th century the number of ethnic Germans grew. After declining at the end of the 19th century,The 1880, 1890, 1900 and 1910 Austrian censuses asked people about the language they use. (Siwek 1996, 31.) at the beginning of the 20th century and later from 1920 to 1938 the Czech population grew significantly to rival the Poles. Another significant ethnic group were the Jews, but almost the entire Jewish population was murdered during World War II by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

In addition to the Polish, Czech and German national orientations there was another group of Silesians

Silesians (; Silesian German: ''Schläsinger'' ''or'' ''Schläsier''; ; ; ) is both an ethnic as well as a geographical term for the inhabitants of Silesia, a historical region in Central Europe divided by the current national boundaries o ...

, who claimed to be of a distinct national identity. This group enjoyed popular support throughout Cieszyn Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia, Těšín Silesia or Teschen Silesia ( ; or ; or ) is a historical region in south-eastern Silesia, centered on the towns of Cieszyn and Český Těšín and bisected by the Olza River. Since 1920 it has been divided betwe ...

, though its strongest supporters were among the Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

in the eastern part of Cieszyn Silesia (now part of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

), not in Trans-Olza itself.

Name and territory

The Polish term ''Zaolzie'' (meaning "lands beyond the Olza") is used predominantly in Poland and by the Polish minority living in the territory. It is also often used by foreign scholars, e.g. American ethnolinguist Kevin Hannan. The term ''Zaolzie'' was first used in 1930s by Polish writer Paweł Hulka-Laskowski. In Czech it is mainly referred to as ''České Těšínsko''/''Českotěšínsko'' ("land aroundČeský Těšín

Český Těšín (; ; ) is a town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 23,000 inhabitants.

Český Těšín lies on the west bank of the Olza (river), Olza river, in the heart of the historical ...

"), or as ''Těšínsko'' or ''Těšínské Slezsko'' (meaning Cieszyn Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia, Těšín Silesia or Teschen Silesia ( ; or ; or ) is a historical region in south-eastern Silesia, centered on the towns of Cieszyn and Český Těšín and bisected by the Olza River. Since 1920 it has been divided betwe ...

). The Czech equivalent of Zaolzie (''Zaolší'' or ''Zaolží'') is rarely used.

The term Zaolzie denotes the territory of the former districts of Český Těšín

Český Těšín (; ; ) is a town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 23,000 inhabitants.

Český Těšín lies on the west bank of the Olza (river), Olza river, in the heart of the historical ...

and Fryštát

Fryštát (; ; ; Cieszyn Silesia dialect, Cieszyn Silesian: ) is an administrative part of the city of Karviná in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. Until 1948 it was a separate town. It lies on the Olza River, in the historic ...

, in which the Polish population formed a majority according to the 1910 Austrian census.Szymeczek 2008, 63. It makes up the eastern part of the Czech portion of Cieszyn Silesia. However, Polish historian Józef Szymeczek notes that the term is often mistakenly used for the whole Czech part of Cieszyn Silesia.

Since the 1960 reform of administrative divisions of Czechoslovakia, Trans-Olza has consisted of Karviná District

Karviná District () is a Okres, district in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. Its capital is the city of Karviná, but the most populated city is Havířov.

Administrative division

Karviná District is divided into five Distric ...

and the eastern part of Frýdek-Místek District.

History

After theMigration Period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

the area was settled by West Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic langu ...

, which were later organized into the Golensizi tribe. The tribe had a large and important gord situated in contemporary Chotěbuz. In the 880s or the early 890s the gord was raided and burned, most probably by an army of Svatopluk I of Moravia

Svatopluk I or Svätopluk I, also known as Svatopluk the Great, was a ruler of Great Moravia, which attained its maximum territorial expansion during his reign (870–871, 871–894).

Svatopluk's career started in the 860s, when he govern ...

, and afterwards the area could have been subjugated by Great Moravia

Great Moravia (; , ''Meghálī Moravía''; ; ; , ), or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavic to emerge in the area of Central Europe, possibly including territories which are today part of the Czech Repub ...

, which is however questioned by historians like Zdeněk Klanica, Idzi Panic, Stanisław Szczur.

After the fall of Great Moravia in 907 the area could have been under the influence of

After the fall of Great Moravia in 907 the area could have been under the influence of Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, originally practised by 19th–20th century European and American artists and writers.

* Bohemian style, a ...

rulers. In the late 10th century Poland, ruled by Bolesław I Chrobry, began to contend for the region, which was crossed by important international routes. From 950 to 1060 it was under the rule of Bohemia, and from 1060 it was part of the Piast Kingdom of Poland. The written history explicitly about the region begins on 23 April 1155 when Cieszyn/Těšín was first mentioned in a written document, a letter from Pope Adrian IV

Pope Adrian (or Hadrian) IV (; born Nicholas Breakspear (or Brekespear); 1 September 1159) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 4 December 1154 until his death in 1159. Born in England, Adrian IV was the first Pope ...

issued for Walter, Bishop of Wrocław, where it was listed amongst other centres of castellanies. The castellany was then a part of Duchy of Silesia

The Duchy of Silesia (, ) with its capital at Wrocław was a medieval provincial duchy of Poland located in the region of Silesia. Soon after it was formed under the Piast dynasty in 1138, it fragmented into various Silesian duchies. In 1327, t ...

. In 1172 it became a part of Duchy of Racibórz

Duchy of Racibórz (, , ) was one of the duchies of Silesia, formed during the medieval fragmentation of Poland into provincial duchies. Its capital was Racibórz in Upper Silesia.

States and territories disestablished in the 1200s

States and ...

, and from 1202 of Duchy of Opole and Racibórz. In the first half of the 13th century the Moravian settlement organised by Arnold von Hückeswagen from Starý Jičín castle and later accelerated by Bruno von Schauenburg, Bishop of Olomouc, began to press close to Silesian settlements. This prompted signing of a special treaty between Duke Vladislaus I of Opole and King Ottokar II of Bohemia

Ottokar II (; , in Městec Králové, Bohemia – 26 August 1278, in Dürnkrut, Austria, Dürnkrut, Lower Austria), the Iron and Golden King, was a member of the Přemyslid dynasty who reigned as King of Bohemia from 1253 until his death in 1278 ...

on December 1261 which regulated a local border between their states along the Ostravice River. In order to strengthen the border Władysław of Opole decided to found Orlová monastery

The Orlová monastery (, ) was a Order of St. Benedict, Benedictine abbey established around 1268 in what is now a town of Orlová in the Karviná District, Moravian-Silesian Region, Czech Republic.

History

Orlová was first mentioned in a writ ...

in 1268. In the continued process of feudal fragmentation of Poland the Castellany of Cieszyn was eventually transformed in 1290 into the Duchy of Cieszyn, which in 1327 became an autonomic fiefdom

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

of the Bohemian crown. Upon the death of Elizabeth Lucretia, its last ruler from the Polish Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented List of Polish monarchs, Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I of Poland, Mieszko I (–992). The Poland during the Piast dynasty, Piasts' royal rule in Pol ...

in 1653, it passed directly to the Bohemian kings from the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

dynasty. When most of Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

was conquered by Prussian king Frederick the Great

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself ''King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prussia ...

in 1742, the Cieszyn region was part of the small southern portion that was retained by the Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

(Austrian Silesia

Austrian Silesia, officially the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia, was an autonomous region of the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Habsburg monarchy (from 1804 the Austrian Empire, and from 1867 the Cisleithanian portion of Austria-Hungary). It is la ...

).

Up to the mid-19th century members of the local Slav population did not identify themselves as members of larger ethnolinguistic entities. In Cieszyn Silesia (as in all West Slavic borderlands) various territorial identities pre-dated ethnic and national identity. Consciousness of membership within a greater Polish or Czech nation spread slowly in Silesia.

From 1848 to the end of the 19th century, local Polish and Czech people co-operated, united against the Germanizing tendencies of the

Up to the mid-19th century members of the local Slav population did not identify themselves as members of larger ethnolinguistic entities. In Cieszyn Silesia (as in all West Slavic borderlands) various territorial identities pre-dated ethnic and national identity. Consciousness of membership within a greater Polish or Czech nation spread slowly in Silesia.

From 1848 to the end of the 19th century, local Polish and Czech people co-operated, united against the Germanizing tendencies of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and later of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. At the end of the century, ethnic tensions arose as the area's economic significance grew. This growth caused a wave of immigration from Galicia. About 60,000 people arrived between 1880 and 1910. The new immigrants were Polish and poor, about half of them being illiterate. They worked in coal mining and metallurgy. For these people the most important factor was material well-being; they cared little about the homeland from which they had fled. Almost all of them assimilated into the Czech population. Many of them settled in Ostrava

Ostrava (; ; ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 283,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four rivers: Oder, Opava (river), Opa ...

(west of the ethnic border), as heavy industry was spread through the whole western part of Cieszyn Silesia. Even today, ethnographers find that about 25,000 people in Ostrava (about 8% of the population) have Polish surnames.

The Czech population (living mainly in the northern part of the area: Bohumín

Bohumín (; , ) is a town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 20,000 inhabitants.

Administrative division

Bohumín consists of seven municipal parts (in brackets population according to the 202 ...

, Orlová

Orlová (; , ) is a town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 28,000 inhabitants. The town is struggling with structural problems and is infamously known as the worst town to live in in the Czech ...

, etc.) declined numerically at the end of the 19th century, assimilating with the prevalent Polish population. This process shifted with the industrial boom in the area.

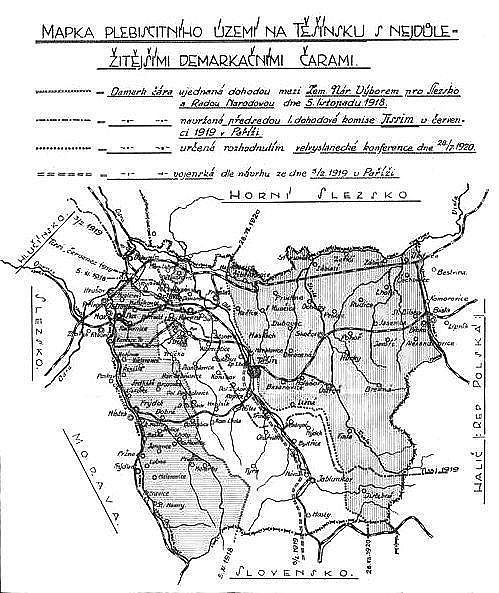

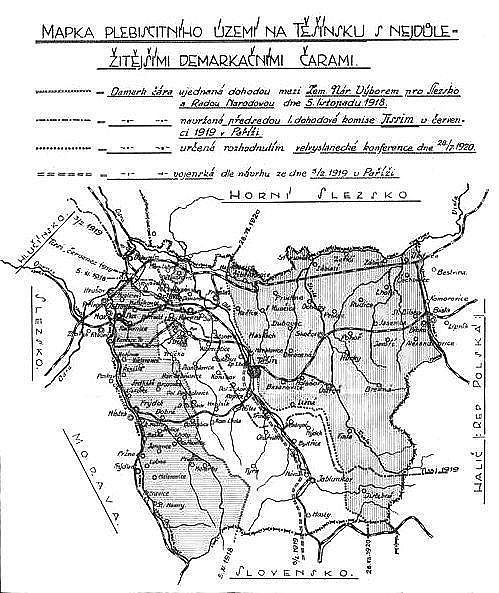

Decision time (1918–1920)

Cieszyn Silesia was claimed by both Poland and Czechoslovakia: the Polish ''Rada Narodowa Księstwa Cieszyńskiego'' made its claim in its declaration "Ludu śląski!" of 30 October 1918, and the Czech ''Zemský národní výbor pro Slezsko'' did so in its declaration of 1 November 1918.Gawrecká 2004, 21. On 31 October 1918, at the end of World War I and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the majority of the area was taken over by local Polish authorities supported by armed forces. An interim agreement from 2 November 1918 reflected the inability of the two national councils to come to final

Cieszyn Silesia was claimed by both Poland and Czechoslovakia: the Polish ''Rada Narodowa Księstwa Cieszyńskiego'' made its claim in its declaration "Ludu śląski!" of 30 October 1918, and the Czech ''Zemský národní výbor pro Slezsko'' did so in its declaration of 1 November 1918.Gawrecká 2004, 21. On 31 October 1918, at the end of World War I and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the majority of the area was taken over by local Polish authorities supported by armed forces. An interim agreement from 2 November 1918 reflected the inability of the two national councils to come to final delimitation

Electoral boundary delimitation (or simply boundary delimitation or delimitation) is the drawing of boundaries of electoral precincts and related divisions involved in elections, such as Federated state, states, counties or other municipalities ...

and on 5 November 1918, the area was divided between Poland and Czechoslovakia by an agreement of the two councils. In early 1919 both councils were absorbed by the newly created and independent central governments in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

and Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

.

Following an announcement that elections to the Sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

(parliament) of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

would be held in the entirety of Cieszyn Silesia, the Czechoslovak government requested that the Poles cease their preparations as no elections were to be held in the disputed territory until a final agreement could be reached. When their demands were rejected by the Poles, the Czechs decided to resolve the issue by force and on 23 January 1919 invaded the area.

The Czechoslovak offensive was halted after pressure from the Entente following the Battle of Skoczów, and a ceasefire was signed on 3 February. The new Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

claimed the area partly on historic and ethnic grounds, but especially on economic grounds.Mamatey 1973, 34. The area was important for the Czechs as the crucial railway line connecting Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (; ) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. While it currently has no formal boundaries, in a narrow geographic sense, it encompasses most or all of the territory of the Czech Republic within the ...

with Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

crossed the area (the Košice–Bohumín Railway, which was one of only two railroads that linked the Czech provinces to Slovakia at that time). The area is also very rich in black coal. Many important coal mines, facilities and metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

factories are located there. The Polish side based its claim to the area on ethnic criteria: a majority (69.2%) of the area's population was Polish according to the last (1910) Austrian census.Dariusz Miszewski. ''Aktywność polityczna mniejszości polskiej w Czechosłowacji w latach 1920-1938''. Wyd. Adam Marszałek. 2002. p. 346.

In this very tense atmosphere it was decided that a plebiscite would be held in the area asking people which country this territory should join. Plebiscite commissioners arrived there at the end of January 1920, and after analysing the situation declared a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

in the territory on 19 May 1920. The situation in the area remained very tense, with mutual intimidation, acts of terror, beatings and even killings. A plebiscite could not be held in this atmosphere. On 10 July both sides renounced the idea of a plebiscite and entrusted the Conference of Ambassadors with the decision.Zahradnik 1992, 64. Eventually, on 28 July 1920, by a decision of the Spa Conference, Czechoslovakia received 58.1% of the area of Cieszyn Silesia, containing 67.9% of the population. It was this territory that became known from the Polish standpoint as ''Zaolzie'' – the Olza River marked the boundary between the Polish and Czechoslovak parts of the territory.

The most vocal support for union with Poland had come from within the territory awarded to Czechoslovakia, while some of the strongest opponents of Polish rule came from the territory awarded to Poland.

View of Richard M. Watt

Historian Richard M. Watt writes, "On 5 November 1918, the Poles and the Czechs in the region disarmed the Austrian garrison (...) The Poles took over the areas that appeared to be theirs, just as the Czechs had assumed administration of theirs. Nobody objected to this friendly arrangement (...) Then came second thoughts in

Historian Richard M. Watt writes, "On 5 November 1918, the Poles and the Czechs in the region disarmed the Austrian garrison (...) The Poles took over the areas that appeared to be theirs, just as the Czechs had assumed administration of theirs. Nobody objected to this friendly arrangement (...) Then came second thoughts in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

. It was observed that under the agreement of 5 November, the Poles controlled about a third of the duchy's coal mines. The Czechs realized that they had given away rather a lot (...) It was recognized that any takeover in Cieszyn would have to be accomplished in a manner acceptable by the victorious Allies (...), so the Czechs cooked up a tale that the Cieszyn area was becoming Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

(...) The Czechs put together a substantial body of infantry – about 15,000 men – and on 23 January 1919, they invaded the Polish-held areas. To confuse the Poles, the Czechs recruited some Allied officers of Czech background and put these men in their respective wartime uniforms at the head of the invasion forces. After a little skirmishing, the tiny Polish defense force was nearly driven out."

In 1919, the matter went to consideration in Paris before the World War I Allies. Watt claims the Poles based their claims on ethnographical reasons and the Czechs based their need on the Cieszyn coal, useful in order to influence the actions of Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, whose capitals were fuelled by coal from the duchy. The Allies finally decided that the Czechs should get 60 percent of the coal fields and the Poles were to get most of the people and the strategic rail line. Watt writes: "Czech envoy Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1939 to 1948. During the first six years of his second stint, he led the Czec ...

proposed a plebiscite. The Allies were shocked, arguing that the Czechs were bound to lose it. However, Beneš was insistent and a plebiscite was announced in September 1919. As it turned out, Beneš knew what he was doing. A plebiscite would take some time to set up, and a lot could happen in that time – particularly when a nation's affairs were conducted as cleverly as were Czechoslovakia's."Watt 1998, 163.

Watt argues that Beneš strategically waited for Poland's moment of weakness, and moved in during the Polish-Soviet War crisis in July 1920. As Watt writes, "Over the dinner table, Beneš convinced the British and French that the plebiscite should not be held and that the Allies should simply impose their own decision in the Cieszyn matter. More than that, Beneš persuaded the French and the British to draw a frontier line that gave Czechoslovakia most of the territory of Cieszyn, the vital railroad and all the important coal fields. With this frontier, 139,000 Poles were to be left in Czech territory, whereas only 2,000 Czechs were left on the Polish side".

"The next morning Beneš visited the Polish delegation at Spa. By giving the impression that the Czechs would accept a settlement favorable to the Poles without a plebiscite, Beneš got the Poles to sign an agreement that Poland would abide by any Allied decision regarding Cieszyn. The Poles, of course, had no way of knowing that Beneš had already persuaded the Allies to make a decision on Cieszyn. After a brief interval, to make it appear that due deliberation had taken place, the Allied Council of Ambassadors in Paris imposed its 'decision'. Only then did it dawn on the Poles that at Spa they had signed a blank check. To them, Beneš' stunning triumph was not diplomacy, it was a swindle (...) As Polish Prime Minister

Watt argues that Beneš strategically waited for Poland's moment of weakness, and moved in during the Polish-Soviet War crisis in July 1920. As Watt writes, "Over the dinner table, Beneš convinced the British and French that the plebiscite should not be held and that the Allies should simply impose their own decision in the Cieszyn matter. More than that, Beneš persuaded the French and the British to draw a frontier line that gave Czechoslovakia most of the territory of Cieszyn, the vital railroad and all the important coal fields. With this frontier, 139,000 Poles were to be left in Czech territory, whereas only 2,000 Czechs were left on the Polish side".

"The next morning Beneš visited the Polish delegation at Spa. By giving the impression that the Czechs would accept a settlement favorable to the Poles without a plebiscite, Beneš got the Poles to sign an agreement that Poland would abide by any Allied decision regarding Cieszyn. The Poles, of course, had no way of knowing that Beneš had already persuaded the Allies to make a decision on Cieszyn. After a brief interval, to make it appear that due deliberation had taken place, the Allied Council of Ambassadors in Paris imposed its 'decision'. Only then did it dawn on the Poles that at Spa they had signed a blank check. To them, Beneš' stunning triumph was not diplomacy, it was a swindle (...) As Polish Prime Minister Wincenty Witos

Wincenty Witos (; 21 or 22 January 1874 – 31 October 1945) was a Polish statesman, prominent member and leader of the Polish People's Party (PSL), who served three times as the Prime Minister of Poland in the 1920s.

He was a member of the Pol ...

warned: 'The Polish nation has received a blow which will play an important role in our relations with the Czechoslovak Republic. The decision of the Council of Ambassadors has given the Czechs a piece of Polish land containing a population which is mostly Polish.... The decision has caused a rift between these two nations which are ordinarily politically and economically united' (

...."

View of Victor S. Mamatey

Another account of the situation in 1918–1919 is given by Slovak-American historian Victor S. Mamatey. He notes that when the French government recognised Czechoslovakia's right to the "boundaries ofBohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

, Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

, and Austrian Silesia

Austrian Silesia, officially the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia, was an autonomous region of the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Habsburg monarchy (from 1804 the Austrian Empire, and from 1867 the Cisleithanian portion of Austria-Hungary). It is la ...

" in its note to Austria of 19 December, the Czechoslovak government acted under the impression it had French support for its claim to Cieszyn Silesia as part of Austrian Silesia. However, Paris believed it gave that assurance only against German-Austrian claims, not Polish ones. Paris, however, viewed both Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

as potential allies against Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and did not want to cool relations with either. Mamatey writes that the Poles "brought the matter before the peace conference that had opened in Paris on 18 January. On 29 January, the Council of Ten summoned Beneš and the Polish delegate Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski Polish: (9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939) was a Polish right-wing politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement ...

to explain the dispute, and on 1 February obliged them to sign an agreement redividing the area pending its final disposition by the peace conference. Czechoslovakia thus failed to gain her objective in Cieszyn."

With respect to the arbitration decision itself, Mamatey writes that "On 25 March, to expedite the work of the peace conference, the Council of Ten was divided into the Council of Four (The "Big Four") and the Council of Five (the foreign ministers). Early in April the two councils considered and approved the recommendations of the Czechoslovak commission without a change – with the exception of Cieszyn, which they referred to Poland and Czechoslovakia to settle in bilateral negotiations." When the Polish-Czechoslovak negotiations failed, the Allied powers proposed plebiscites in the Cieszyn Silesia and also in the border districts of Orava and Spiš

Spiš ( ; or ; ) is a region in north-eastern Slovakia, with a very small area in south-eastern Poland (more specifically encompassing 14 former Slovak villages). Spiš is an informal designation of the territory, but it is also the name of one ...

(now in Slovakia) to which the Poles had raised claims. In the end, however, no plebiscites were held due to the rising mutual hostilities of Czechs and Poles in Cieszyn Silesia. Instead, on 28 July 1920 the Spa Conference (also known as the Conference of Ambassadors) divided each of the three disputed areas between Poland and Czechoslovakia.

Part of Czechoslovakia (1920–1938)

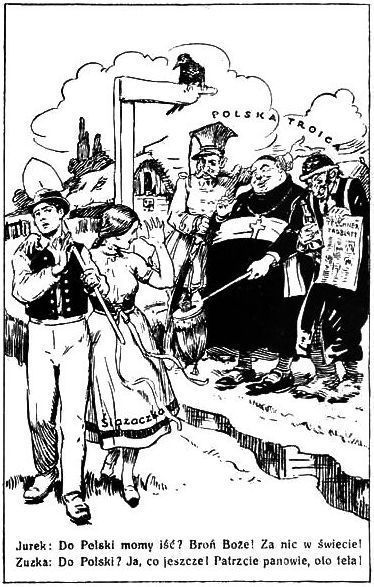

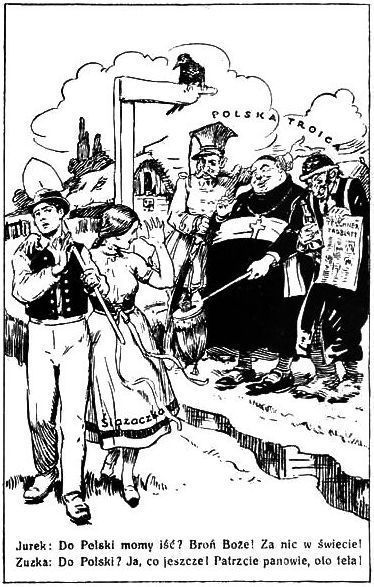

The local Polish population felt that Warsaw had betrayed them and they were not satisfied with the division of Cieszyn Silesia. About 12,000 to 14,000 Poles were forced to leave to Poland.Gabal 1999, 120. It is not quite clear how many Poles were in Trans-Olza in Czechoslovakia. Estimates (depending mainly whether the

The local Polish population felt that Warsaw had betrayed them and they were not satisfied with the division of Cieszyn Silesia. About 12,000 to 14,000 Poles were forced to leave to Poland.Gabal 1999, 120. It is not quite clear how many Poles were in Trans-Olza in Czechoslovakia. Estimates (depending mainly whether the Silesians

Silesians (; Silesian German: ''Schläsinger'' ''or'' ''Schläsier''; ; ; ) is both an ethnic as well as a geographical term for the inhabitants of Silesia, a historical region in Central Europe divided by the current national boundaries o ...

are included as Poles or not) range from 110,000 to 140,000 people in 1921. The 1921 and 1930 census numbers are not accurate since nationality depended on self-declaration and many Poles filled in Czech nationality mainly as a result of fear of the new authorities and as compensation for some benefits. Czechoslovak law guaranteed rights for national minorities but reality in Trans-Olza was quite different.Zahradnik 1992, 76–79. Local Czech authorities made it more difficult for local Poles to obtain citizenship, while the process was expedited when the applicant pledged to declare Czech nationality and send his children to a Czech school. Newly built Czech schools were often better supported and equipped, thus inducing some Poles to send their children there. Czech schools were built in ethnically almost entirely Polish municipalities. This and other factors contributed to the cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's Dominant culture, majority group or fully adopts the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group. The melting pot model is based on this ...

of Poles and also to significant emigration to Poland. After a few years, the heightened nationalism typical for the years around 1920 receded and local Poles increasingly co-operated with Czechs. Still, Czechization

Czechization or Czechisation (; ) is a cultural change in which something ethnically non-Czech is made to become Czech.

This concept is especially relevant in relation to the Germans of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia as well as the Poles of T ...

was supported by Prague, which did not follow certain laws related to language, legislative and organizational issues. Polish deputies in the Czechoslovak National Assembly frequently tried to put those issues on agenda. One way or another, more and more local Poles thus assimilated into the Czech population.

Part of Poland (1938–1939)

Within the region originally demanded from Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in 1938 was the important railway junction city of

Within the region originally demanded from Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in 1938 was the important railway junction city of Bohumín

Bohumín (; , ) is a town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 20,000 inhabitants.

Administrative division

Bohumín consists of seven municipal parts (in brackets population according to the 202 ...

(). The Poles regarded the city as of crucial importance to the area and to Polish interests. On 28 September, Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš (; 28 May 1884 – 3 September 1948) was a Czech politician and statesman who served as the president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938, and again from 1939 to 1948. During the first six years of his second stint, he led the Czec ...

composed a note to the Polish administration offering to reopen the debate surrounding the territorial demarcation in Těšínsko in the interest of mutual relations, but he delayed in sending it in hopes of good news from London and Paris, which came only in a limited form. Beneš then turned to the Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

leadership in Moscow, which had begun a partial mobilisation in eastern Belarus and the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

on 22 September and threatened Poland with the dissolution of the Soviet-Polish non-aggression pact. The Czech government was offered 700 fighter planes if room for them could be found on the Czech airfields. On 28 September, all the military districts west of the Urals were ordered to stop releasing men for leave. On 29 September 330,000 reservists were up throughout the western USSR.

Nevertheless, the Polish Foreign Minister, Colonel Józef Beck

Józef Beck (; 4 October 1894 – 5 June 1944) was a Polish statesman who served the Second Republic of Poland as a diplomat and military officer. A close associate of Józef Piłsudski, Beck is most famous for being Polish foreign minister in ...

, believed that Warsaw should act rapidly to forestall the German occupation of the city. At noon on 30 September, Poland gave an ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government. It demanded the immediate evacuation of Czechoslovak troops and police and gave Prague time until noon the following day. At 11:45 a.m. on 1 October the Czechoslovak foreign ministry called the Polish ambassador in Prague and told him that Poland could have what it wanted. The Polish Army, commanded by General Władysław Bortnowski

Władysław Bortnowski (12 November 1891 – 21 November 1966) was a Polish historian, military commander and one of the highest ranking generals of the Polish Army, generals of the Polish Army. He is most famous for commanding the Pomorze Army ...

, annexed an area of 801.5 km2 with a population of 227,399 people. Administratively the annexed area was divided between two counties: Frysztat and Cieszyn County. At the same time Slovakia lost to Hungary 10,390 km2 with 854,277 inhabitants.

The Germans were delighted with this outcome, and were happy to give up the sacrifice of a small provincial rail centre to Poland in exchange for the ensuing propaganda benefits. It spread the blame of the partition of the Republic of Czechoslovakia, made Poland a participant in the process and confused political expectations. Poland was accused of being an accomplice of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

– a charge that Warsaw was hard-put to deny.Watt 1998, 386.

The Polish side argued that Poles in Trans-Olza deserved the same ethnic rights and freedom as the Sudeten Germans

German Bohemians ( ; ), later known as Sudeten Germans ( ; ), were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part of Czechoslovakia. Before 1945, over three million German Bohemians constitute ...

under the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

. The vast local Polish population enthusiastically welcomed the change, seeing it as a liberation and a form of historical justice, but they quickly changed their mood. The new Polish authorities appointed people from Poland to various key positions from which locals were fired.Gabal 1999, 123. The Polish language became the sole official language. Using Czech (or German) by Czechs (or Germans) in public was prohibited and Czechs and Germans were being forced to leave the annexed area or become subject to Polonization

Polonization or Polonisation ()In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэяй. Польскі ...

. Rapid Polonization policies then followed in all parts of public and private life. Czech organizations were dismantled and their activity was prohibited. The Roman Catholic parishes in the area belonged either to the Archdiocese of Breslau (Archbishop Bertram) or to the Archdiocese of Olomouc (Archbishop Leopold Prečan), respectively, both traditionally comprising cross-border diocesan territories in Czechoslovakia and Germany. When the Polish government demanded after its takeover that the parishes there be disentangled from these two archdioceses, the Holy See complied. Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

, former nuncio to Poland, subjected the Catholic parishes in Trans-Olza to an apostolic administration

An apostolic administration in the Catholic Church is administrated by a prelate appointed by the pope to serve as the ordinary for a specific area. Either the area is not yet a diocese (a stable 'pre-diocesan', usually missionary apostolic admi ...

under Stanisław Adamski, Bishop of Katowice.Jerzy Pietrzak, "Die politischen und kirchenrechtlichen Grundlagen der Einsetzung Apostolischer Administratoren in den Jahren 1939–1942 und 1945 im Vergleich", in: ''Katholische Kirche unter nationalsozialistischer und kommunistischer Diktatur: Deutschland und Polen 1939–1989'', Hans-Jürgen Karp and Joachim Köhler (eds.), (=Forschungen und Quellen zur Kirchen- und Kulturgeschichte Ostdeutschlands; vol. 32), Cologne: Böhlau, 2001, pp. 157–174, here p. 160. .

Czechoslovak education in the Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

and German language ceased to exist. About 35,000 Czechoslovaks emigrated to core Czechoslovakia (the later Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was a partially-annexation, annexed territory of Nazi Germany that was established on 16 March 1939 after the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945), German occupation of the Czech lands. The protector ...

) by choice or forcibly. The behaviour of the new Polish authorities was different but similar in nature to that of the Czechoslovak ones before 1938. Two political factions appeared: socialists (the opposition) and rightists (loyal to the new Polish national authorities). Leftist politicians and sympathizers were discriminated against and often fired from work. The Polish political system was artificially implemented in Trans-Olza. The local Poles continued to feel like second-class citizens and a majority of them were dissatisfied with the situation after October 1938. Zaolzie remained a part of Poland for only 11 months until the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

started on 1 September 1939.

Reception

When Poland entered the Western camp in April 1939, General Gamelin reminded General Kasprzycki of the Polish role in the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. According to historian Paul N. Hehn, Poland's annexation of Zaolzie may have contributed to the British and French reluctance to attack the Germans with greater forces in September 1939. Richard M. Watt describes the Polish capture of Zaolzie in these words:Amid the general euphoria in Poland – the acquisition of Zaolzie was a very popular development – no one paid attention to the bitter comment of the Czechoslovak general who handed the region over to the incoming Poles. He predicted that it would not be long before the Poles would themselves be handing Zaolzie over to the Germans.Watt also writes that

the Polish 1938 ultimatum to Czechoslovakia and its acquisition of Zaolzie were gross tactical errors. Whatever justice there might have been to the Polish claim upon Zaolzie, its seizure in 1938 was an enormous mistake in terms of the damage done to Poland's reputation among the democratic powers of the world.Daladier, the French Prime Minister, told the US ambassador to France that "he hoped to live long enough to pay Poland for her cormorant attitude in the present crisis by proposing a new partition." The Soviet Union was so hostile to Poland over Munich that there was a real prospect that war between the two states might break out quite separate from the wider conflict over Czechoslovakia. The Soviet Prime Minister, Molotov, denounced the Poles as "Hitler's jackals". In his postwar memoirs,

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

compared Germany and Poland to vultures landing on the dying carcass of Czechoslovakia and lamented that "over a question so minor as Cieszyn, they he Polessundered themselves from all those friends in France, Britain and the United States who had lifted them once again to a national, coherent life, and whom they were soon to need so sorely. ... It is a mystery and tragedy of European history that a people capable of every heroic virtue ... as individuals, should repeatedly show such inveterate faults in almost every aspect of their governmental life." Churchill also associated such behaviour with hyenas

Hyenas or hyaenas ( ; from Ancient Greek , ) are feliformia, feliform carnivoran mammals belonging to the Family (biology), family Hyaenidae (). With just four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the orde ...

.

In 2009 Polish president Lech Kaczyński

Lech Aleksander Kaczyński (; 18 June 194910 April 2010) was a Polish politician who served as the city mayor of Warsaw from 2002 until 2005, and as President of Poland from 2005 until his death in 2010 in an air crash. The aircraft carrying ...

declared during 70th anniversary of start of World War II, which was welcomed by the Czech and Slovak diplomatic delegations:

The Polish annexation of Zaolzie is frequently brought up by Russian media

Television, magazines, and newspapers have all been operated by both state-owned and for-profit corporations which depend on advertising, subscription, and other sales-related revenues. Even though the Constitution of Russia guarantees freed ...

as a counter-argument to Soviet-Nazi cooperation.

World War II

On 1 September 1939 Nazi Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II in Europe, and subsequently made Trans-Olza part of the ''Military district of Upper Silesia''. On 26 October 1939 Nazi Germany unilaterally annexed Trans-Olza as part of Landkreis Teschen. During the war, strongGermanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people, and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nati ...

was introduced by the authorities. The Jews were in the worst position, followed by the Poles.Zahradnik 1992, 99. Poles received lower food rations, they were supposed to pay extra taxes, they were not allowed to enter theatres, cinemas, etc. Polish and Czech education ceased to exist, Polish organizations were dismantled and their activity was prohibited. Katowice's Bishop Adamski was deposed as apostolic administrator for the Catholic parishes in Trans-Olza and on 23 December 1939 Cesare Orsenigo, nuncio to Germany, returned them to their original archdioceses of Breslau or Olomouc, respectively, with effect of 1 January 1940.

The German authorities introduced terror into Trans-Olza. The Nazis especially targeted the Polish intelligentsia, many of whom died during the war. Mass killings, executions, arrests, taking locals to forced labour and deportations to concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

all happened on a daily basis. The most notorious war crime was a murder of 36 villagers in and around Żywocice on 6 August 1944. This massacre is known as the Żywocice tragedy (). The resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

, mostly composed of Poles, was fairly strong in Trans-Olza. So-called '' Volksliste'' – a document in which a non-German citizen declared that he had some German ancestry by signing it; refusal to sign this document could lead to deportation to a concentration camp – were introduced. Local people who took them were later on enrolled in the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

. Many local people with no German ancestry were also forced to take them. The World War II death toll in Trans-Olza is estimated at about 6,000 people: about 2,500 Jews, 2,000 other citizens (80% of them being Poles)Zahradnik 1992, 103. and more than 1,000 locals who died in the Wehrmacht (those who took the Volksliste). Also a few hundred Poles from Trans-Olza were murdered by Soviets in the Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre was a series of mass killings under Communist regimes, mass executions of nearly 22,000 Polish people, Polish military officer, military and police officers, border guards, and intelligentsia prisoners of war carried out by t ...

.

Percentage-wise, Trans-Olza suffered the worst human loss from the whole of Czechoslovakia – about 2.6% of the total population.

Since 1945

Immediately after World War II, Trans-Olza was returned to Czechoslovakia within its 1920 borders, although local Poles had hoped it would again be given to Poland. Most Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovaks of German ethnicity were expelled, and the local Polish population again suffered discrimination, as many Czechs blamed them for the discrimination by the Polish authorities in 1938–1939. Polish organizations were banned, and the Czechoslovak authorities carried out many arrests and dismissed many Poles from work. The situation had somewhat improved when the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took power in February 1948. Polish property deprived by the German occupants during the war was never returned.

As to the Catholic parishes in Trans-Olza pertaining to the Archdiocese of Breslau Archbishop Bertram, then residing in the episcopal Jánský vrch castle in Czechoslovak Javorník (Jeseník District), Javorník, appointed František Onderek (1888–1962) as ''vicar general for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' on 21 June 1945. In July 1946 Pope Pius XII elevated Onderek to ''Apostolic Administrator for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' (colloquially: Apostolic Administration of Český Těšín; ), seated in

Immediately after World War II, Trans-Olza was returned to Czechoslovakia within its 1920 borders, although local Poles had hoped it would again be given to Poland. Most Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovaks of German ethnicity were expelled, and the local Polish population again suffered discrimination, as many Czechs blamed them for the discrimination by the Polish authorities in 1938–1939. Polish organizations were banned, and the Czechoslovak authorities carried out many arrests and dismissed many Poles from work. The situation had somewhat improved when the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took power in February 1948. Polish property deprived by the German occupants during the war was never returned.

As to the Catholic parishes in Trans-Olza pertaining to the Archdiocese of Breslau Archbishop Bertram, then residing in the episcopal Jánský vrch castle in Czechoslovak Javorník (Jeseník District), Javorník, appointed František Onderek (1888–1962) as ''vicar general for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' on 21 June 1945. In July 1946 Pope Pius XII elevated Onderek to ''Apostolic Administrator for the Czechoslovak portion of the Archdiocese of Breslau'' (colloquially: Apostolic Administration of Český Těšín; ), seated in Český Těšín

Český Těšín (; ; ) is a town in Karviná District in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 23,000 inhabitants.

Český Těšín lies on the west bank of the Olza (river), Olza river, in the heart of the historical ...

, thus disentangling the parishes from Breslau's jurisdiction. On 31 May 1978 Pope Paul VI merged the apostolic administration into the Archdiocese of Olomouc through his Apostolic constitution ''Olomoucensis et aliarum''.

People's Republic of Poland, Poland signed a treaty with Czechoslovakia in Warsaw on 13 June 1958 confirming the border as it existed on 1 January 1938. After the Communist takeover of power, the industrial boom continued and many immigrants arrived in the area (mostly from other parts of Czechoslovakia, mainly from Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

). The arrival of Slovaks significantly changed the ethnic structure of the area, as almost all the Slovak immigrants assimilated into the Czech majority in the course of time. The number of self-declared Slovaks is rapidly declining. The last Slovak primary school was closed in Karviná several years ago. Since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, Trans-Olza has been part of the independent Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

. However, a significant Polish minority still remains there.

In the European Union

The entry of both the Czech Republic and

The entry of both the Czech Republic and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

to the European Union in May 2004, and especially the entry of the countries to the EU's passport-free Schengen zone in late 2007, reduced the significance of territorial disputes, ending systematic controls on the border between the countries. Signs prohibiting passage across the state border were removed, with people now allowed to cross the border freely at any point of their choosing.

The area belongs mostly to the Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion with a few municipalities in the Euroregion Beskydy.

Census data

Ethnic structure of Trans-Olza based on census results: Sources: Zahradnik 1992, 178–179. Siwek 1996, 31–38.See also

* History of Cieszyn and Těšín * Polonia Karwina * Independent Operational Group SilesiaFootnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Jarosław Jot-Drużycki: Poles living in Zaolzie identify themselves better with Czechs

. ''European Foundation of Human Rights.'' 3 September 2014.

Documents and photographs about the situation in Zaolzie in 1938

{{good article Historical regions Cieszyn Silesia Czech Republic–Poland border Czechoslovakia–Poland border Czechoslovakia–Poland relations Czechoslovakia–Germany relations Germany–Poland relations (1918–1939) History of Czech Silesia Moravian-Silesian Region Polish minority in Trans-Olza Territorial disputes of Czechoslovakia Territorial disputes of Poland Historical regions in the Czech Republic Interwar Czechoslovakia Former disputed land areas