Terrestrisuchus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Terrestrisuchus'' is an

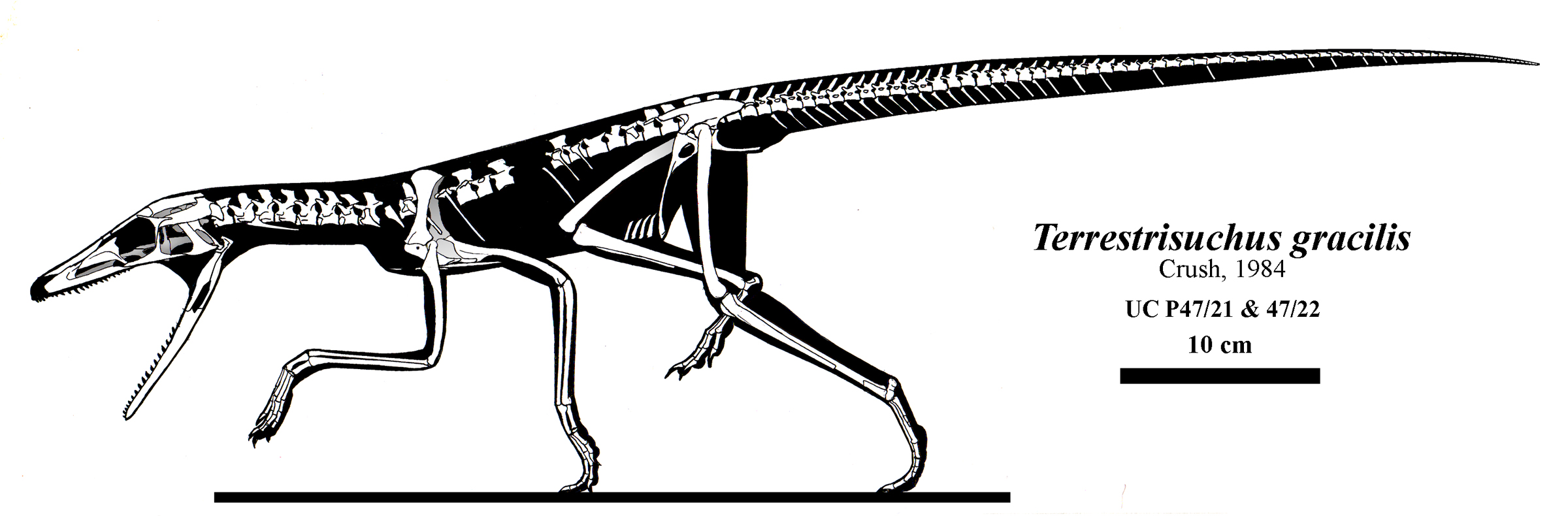

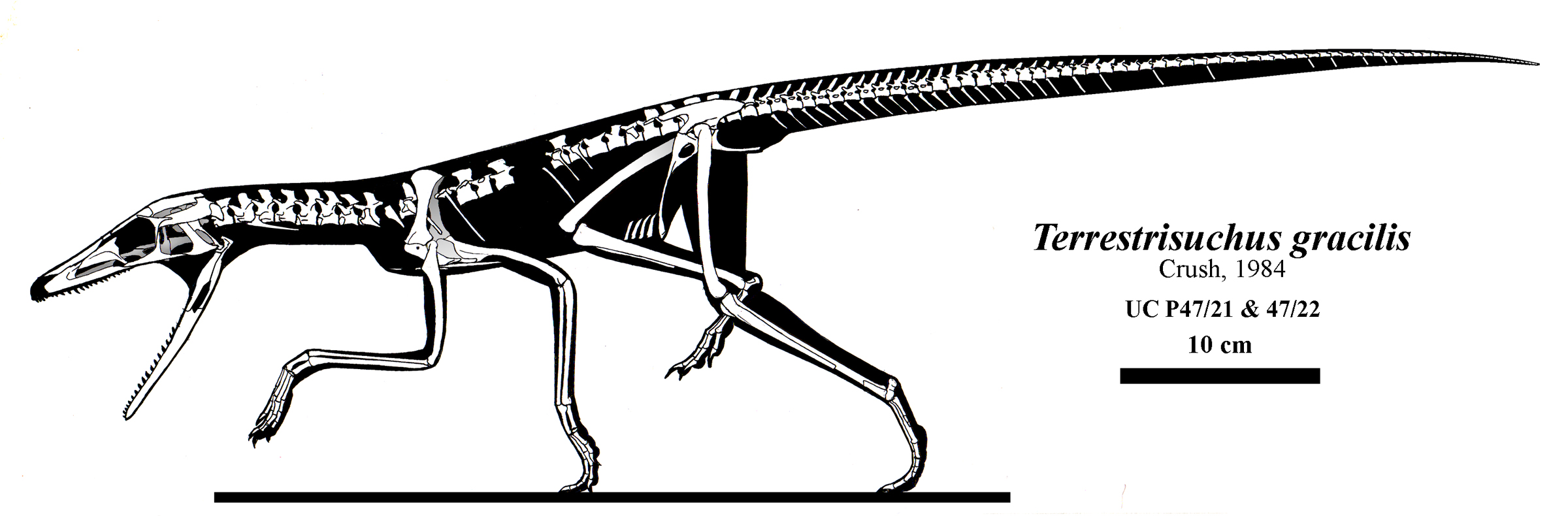

''Terrestrisuchus'' was a small, slender crocodylomorph with very long legs, quite unlike modern crocodilians. It was initially estimated to have been between long, although this estimate may be based on juvenile specimens and fully grown ''Terrestrisuchus'' may have reached or exceeded in length.

Its skull was long and narrow, with a tapering, pointed triangular snout lined with sharp curved teeth. The upper jaw margin was straight, and lacked a diastema (a gap in the tooth row) between the

''Terrestrisuchus'' was a small, slender crocodylomorph with very long legs, quite unlike modern crocodilians. It was initially estimated to have been between long, although this estimate may be based on juvenile specimens and fully grown ''Terrestrisuchus'' may have reached or exceeded in length.

Its skull was long and narrow, with a tapering, pointed triangular snout lined with sharp curved teeth. The upper jaw margin was straight, and lacked a diastema (a gap in the tooth row) between the

Unlike modern crocodylians, the limbs of ''Terrestrisuchus'' were very long in proportion to the body and were held upright directly beneath it. The shape of the ankles and the bones in the hands and feet also suggest that ''Terrestrisuchus'' was

Unlike modern crocodylians, the limbs of ''Terrestrisuchus'' were very long in proportion to the body and were held upright directly beneath it. The shape of the ankles and the bones in the hands and feet also suggest that ''Terrestrisuchus'' was

The thin, serrated teeth of ''Terrestrisuchus'' indicate that it was carnivorous, and like other early crocodylomorphs it was likely a generalist pursuit hunter that preyed upon small to mid-sized prey items. The shape and construction of its hip bones, particularly the elongated pubis, indicate that they were rigidly sutured together and that its pubis was not mobile as it is in modern crocodilians. This indicates that ''Terrestrisuchus'' would not have utilised the

The thin, serrated teeth of ''Terrestrisuchus'' indicate that it was carnivorous, and like other early crocodylomorphs it was likely a generalist pursuit hunter that preyed upon small to mid-sized prey items. The shape and construction of its hip bones, particularly the elongated pubis, indicate that they were rigidly sutured together and that its pubis was not mobile as it is in modern crocodilians. This indicates that ''Terrestrisuchus'' would not have utilised the

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of very small early crocodylomorph

Crocodylomorpha is a group of pseudosuchian archosaurs that includes the crocodilians and their extinct relatives. They were the only members of Pseudosuchia to survive the end-Triassic extinction. Extinct crocodylomorphs were considerably mor ...

that was about long. Fossils have been found in Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

and Southern England

Southern England, also known as the South of England or the South, is a sub-national part of England. Officially, it is made up of the southern, south-western and part of the eastern parts of England, consisting of the statistical regions of ...

and date from near the very end of the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch a ...

during the Rhaetian

The Rhaetian is the latest age (geology), age of the Triassic period (geology), Period (in geochronology) or the uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Triassic system (stratigraphy), System (in chronostratigraphy). It was preceded by the N ...

, and it is known by type

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* ...

and only known species ''T. gracilis''. ''Terrestrisuchus'' was a long-legged, active predator that lived entirely on land, unlike modern crocodilians

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchi ...

. It inhabited a chain of tropical, low-lying islands that made up southern Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, along with similarly small-sized dinosaurs and abundant rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a speciose g ...

ns. Numerous fossils of ''Terrestrisuchus'' are known from fissures in limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

karst

Karst () is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble carbonate rocks such as limestone and Dolomite (rock), dolomite. It is characterized by features like poljes above and drainage systems with sinkholes and caves underground. Ther ...

which made up the islands it lived on, which formed caverns and sinkholes that preserved the remains of ''Terrestrisuchus'' and other island-living reptiles.

Description

maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

and the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

. By contrast, the long and slender dentary bone

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

s of the lower jaw curved slightly upwards towards the front. Unlike modern crocodilians, the eye of ''Terrestrisuchus'' was supported by a ring of bony ossicles, the sclerotic ring

The scleral ring or sclerotic ring is a hardened ring of plates, often derived from bone, that is found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates. Some species of mammals, amphibians, and crocodilians lack scleral rings. The rin ...

.

The body was relatively short and shallow, and the spine was topped by paired rows of osteoderms running down from its neck down its back. These osteoderms are described as "leaf-shaped", being relatively longer than wide with a prominent spur at the front that slides under and interlocks with the scute in front of it. This provides a rigid support for the body and limited the flexibility of its spine, supporting its body on land. The hips of ''Terrestrisuchus'' had an elongated pubis, unlike living crocodilians. ''Terrestrisuchus'' is also known to have had tightly packed gastralia

Gastralia (: gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In these reptil ...

, or belly ribs. Its tail was particularly long, about twice the length of the head and body combined with an estimated 70 caudal vertebra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

e in total, and may have been used as a balance allowing the animal to rear up and run on its hind legs for brief periods.

Limbs and posture

Unlike modern crocodylians, the limbs of ''Terrestrisuchus'' were very long in proportion to the body and were held upright directly beneath it. The shape of the ankles and the bones in the hands and feet also suggest that ''Terrestrisuchus'' was

Unlike modern crocodylians, the limbs of ''Terrestrisuchus'' were very long in proportion to the body and were held upright directly beneath it. The shape of the ankles and the bones in the hands and feet also suggest that ''Terrestrisuchus'' was digitigrade

In terrestrial vertebrates, digitigrade ( ) locomotion is walking or running on the toes (from the Latin ''digitus'', 'finger', and ''gradior'', 'walk'). A digitigrade animal is one that stands or walks with its toes (phalanges) on the ground, and ...

, with elongated metacarpus

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular skeleton, appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones (wrist, wris ...

(wrist) and metatarsal bones

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

that were pressed tightly together, similar to the feet of fast-running dinosaurs, suggesting that ''Terrestrisuchus'' was highly cursorial

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often ...

, adapted for running at high speeds. The pisiform bone

The pisiform bone ( or ), also spelled pisiforme (from the Latin ''pisiformis'', pea-shaped), is a small knobbly, sesamoid bone that is found in the wrist. It forms the ulnar border of the carpal tunnel.

Structure

The pisiform is a sesamoid bone ...

in the wrist is notably smaller compared to early crocodyliforms such as ''Protosuchus

''Protosuchus'' (from , "first" and , "crocodile") is an extinct genus of carnivorous crocodyliform from the Early Jurassic. It is among the earliest animals that resemble crocodilians. ''Protosuchus'' was about in length and about in weight.

...

'', as well as modern crocodilians, indicating that ''Terrestrisuchus'' had less flexible wrists. Crush reconstructed ''Terrestrisuchus'' as a quadruped, with noticeably longer hind limbs than its forelimbs and its hips held high above the shoulder. However, based on these proportions it has also been suggested that ''Terrestrisuchus'' may have been bipedal instead. This question remained controversial in subsequent studies. A quantitative analysis of limb proportions suggested quadrupedal locomotion in early Crurotarsi

Crurotarsi is a clade of archosauriform reptiles that includes crocodilians and stem-crocodilians and possibly bird-line archosaurs too if the extinct, crocodile-like phytosaurs are more distantly related to crocodiles than traditionally though ...

in general, whereas a study of femoral mid-diaphyseal cross sectional geometry supports bipedal locomotion.

Notably, the acetabulum

The acetabulum (; : acetabula), also called the cotyloid cavity, is a wikt:concave, concave surface of the pelvis. The femur head, head of the femur meets with the pelvis at the acetabulum, forming the Hip#Articulation, hip joint.

Structure

The ...

(hip socket) of ''Terrestrisuchus'' is perforated and forms an opening between the hip bones. This feature is otherwise only known in dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

(as well as a few other early crocodylomorphs) and is often regarded as a defining feature of that clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

. Similarly, the femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

of ''Terrestrisuchus'' has a distinct head that faces inwards towards the body, and fits into the hip socket at a right angle to the leg. This condition is described as "buttress-erect", and it is typical of dinosaurs and their close relatives but otherwise unheard of in pseudosuchians

Pseudosuchia, from Ancient Greek ψεύδος (''pseúdos)'', meaning "false", and σούχος (''soúkhos''), meaning "crocodile" is one of two major divisions of Archosauria, including living crocodilians and all archosaurs more closely relat ...

outside of basal crocodylomorphs. Other pseudosuchians with upright limbs were typically "pillar-erect", with their femurs attached into a hip-socket that faced directly downwards. The buttress-erect posture of ''Terrestrisuchus'' and other basal crocodylomorphs is unique amongst crocodile-line archosaurs, and restricted its posture to a permanently upright stance. Its posture was further restricted to an upright gait by the calcaneal tubercle

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel; : calcanei or calcanea) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is th ...

on its heel bone pointing directly backwards from the foot, unlike the back-and-sideways facing tuber of modern, sprawling crocodilians.

History of discovery

The first fossils of ''Terrestrisuchus'' were discovered by Professor K. A. Kermack and Dr.Pamela Lamplugh Robinson

Pamela Lamplugh Robinson (18 December 1919 – 24 October 1994) was a British paleontologist who worked extensively on the fauna of the Triassic and Early Jurassic of Gloucestershire and later worked in India on the Mesozoic and Gondwanan fauna. Sh ...

in the spring of 1952, recovered from the Pant-y-ffynon Quarry located near Cowbridhe, Glamorgan

Glamorgan (), or sometimes Glamorganshire ( or ), was Historic counties of Wales, one of the thirteen counties of Wales that existed from 1536 until their abolishment in 1974. It is located in the South Wales, south of Wales. Originally an ea ...

in South Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

. Their finds were presented by Kermack to the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript a ...

on October 8, 1953, and was recognised belonging to a "primitive crocodile or crocodile ancestor". No osteoderms had been identified yet at the time, which Kermack regarded as representing a "missing link

Missing link may refer to:

Biology

* Missing link (human evolution), a non-scientific term typically referring to transitional fossils

* Piltdown Man, a hoax in which bone fragments were presented as the "missing link" between ape and man

Geog ...

" between modern crocodilians and the Triassic "thecodonts

Thecodontia (meaning 'socket-teeth'), now considered an obsolete taxonomic grouping, was formerly used to describe a diverse "order" of early archosaurian reptiles that first appeared in the latest Permian period and flourished until the end of t ...

". The fossils included several well-preserved articulated partial skeletons and various isolated bones. Kermack refrained from naming the animal or nominating a type specimen, as preparation of the fossils was still ongoing. The specimens were eventually named and thoroughly described by P. J. Crush in 1984, with the generic name ''Terrestrisuchus'' chosen to emphasise the terrestrial lifestyle of this crocodylomorph, and the specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''gracilis'' for its light, graceful build.

The Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry

Pant-y-Ffynnon Quarry is a stone quarry in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, around 3 kilometers east of Cowbridge. It contains fissure fill deposits dating to the Late Triassic (Rhaetian), hosted within karsts of Carboniferous aged limestone, prima ...

is composed mostly of Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

, but the fossils of ''Terrestrisuchus'' were recovered from Triassic sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock formed by the cementation (geology), cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or de ...

s that were deposited within fissures

A fissure is a long, narrow crack opening along the surface of Earth. The term is derived from the Latin word , which means 'cleft' or 'crack'. Fissures emerge in Earth's crust, on ice sheets and glaciers, and on volcanoes.

Ground fissure

A ...

in the limestone (such as sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

s and marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, Clay minerals, clays, and silt. When Lithification, hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

M ...

s). The age of the deposits has been historically debated, with older literature suggesting a Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic series (stratigraphy), Series (or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Triassic Epoch (reference date), Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227.3 ...

to Norian

The Norian is a division of the Triassic geological period, Period. It has the rank of an age (geology), age (geochronology) or stage (stratigraphy), stage (chronostratigraphy). It lasted from ~227.3 to Mya (unit), million years ago. It was prec ...

age. However, palynological

Palynology is the study of microorganisms and microscopic fragments of mega-organisms that are composed of acid-resistant organic material and occur in sediments, sedimentary rocks, and even some metasedimentary rocks. Palynomorphs are the mic ...

data has been used to determine a younger Rhaetian age, close to the very end of the Triassic. This estimate has been corroborated by Rhaetian index fossils

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. "Biostratigraphy." ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of Biology ...

such as conchostraca

Clam shrimp are a group of bivalved branchiopod crustaceans that resemble the unrelated bivalved molluscs. They are extant and also known from the fossil record, from at least the Devonian period and perhaps before. They were originally classifi ...

ns and geomorphological

Geomorphology () is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topography, topographic and bathymetry, bathymetric features generated by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or near Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. Ge ...

data.

Additional material attributed to ''Terrestrisuchus'' has been discovered in other Late Triassic fissure deposits in South Wales and Bristol, including the Ruthin Quarry in Wales and the Tytherington and Cromhall

Cromhall is a village in South Gloucestershire, England. It is located between Bagstone and Charfield on the B4058, and also borders Leyhill. The parish population taken at the 2011 census was 1,231.

Location

Cromhall is about from Falfie ...

quarries near Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

, as well as a possible specimen from Durdham Down

Durdham Down is an area of public open space in Bristol, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and ...

; all of the English remains have been recovered from the Magnesian Conglomerate

The Magnesian Conglomerate is a geological Formation (geology), formation in Clifton, Bristol in England (originally Avon (county), Avon), Gloucestershire and southern Wales, present in Tytherington, Gloucestershire, Tytherington, Durdham Down, S ...

. The fossils of ''Terrestrisuchus'' were originally housed at University College, London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

before being transferred to the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

in London where they are currently stored.

Classification

''Terrestrisuchus'' was originally classified as a member of the crocodylomorphsuborder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

"Sphenosuchia

Sphenosuchia is a suborder of basal crocodylomorphs that first appeared in the Triassic and occurred into the Middle Jurassic. Most were small, gracile animals with an erect limb posture. They are now thought to be ancestral to crocodyliforms ...

", a group that included various other similar long-legged early crocodylomorphs and was considered to be a separate radiation from the group that all later crocodylomorphs would evolve from. However, this classification was made prior to the invention of cladistic

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

phylogenetic analyses, which has since demonstrated that "Sphenosuchia" is an unnatural grouping (paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

), meaning that "sphenosuchians" are not all descended from a single common ancestor to the exclusion of all other crocodylomorphs. Instead, the "sphenosuchians" are a grade of basal crocodylomorphs that lead up to the more derived crocodyliforms

Crocodyliformes is a clade of crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the only pseudo ...

. Nonetheless, ''Terrestrisuchus'' has consistently been recovered within this grade (as shown in the cladogram below).

When describing ''Terrestrisuchus'' in 1984, Crush recognised it shared a close relationship to the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

"sphenosuchian", ''Saltoposuchus

''Saltoposuchus'' is an extinct genus of small (1–1.5 m and 10–15 kg), long-tailed crocodylomorph reptile (Sphenosuchia), from the Norian (Late Triassic) of Europe. The name translated means "leaping foot crocodile". It has been propose ...

''. As such, he erected the new family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Saltoposuchidae for the two genera under "Sphenosuchia". However, few publications since its naming used the name Saltoposuchidae following the adoption of cladistics, in part due to the suggestion that ''Terrestrisuchus'' and ''Saltoposuchus'' were synonymous ( see below). Nonetheless, some early analyses, namely Sereno and Wild (1992), recovered a clade consisting of the two along with the South African form ''Litargosuchus

''Litargosuchus'' is a sphenosuchian crocodylomorph, a basal member of the crocodylomorph clade from the Early Jurassic of South Africa. Its genus name ''Litargosuchus'' is derived from Greek meaning "fast running crocodile" and its species name ...

''. This clade was more recently recovered by Leardi ''et al.'' (2017), who noted that this clade could have approximated Crush's concept of Saltoposuchidae. This suggestion was formalised in 2023, when this clade was phylogentically defined as Saltoposuchidae by Spiekman (2023). The cladogram below depicts the results of his analysis:

Synonymy with ''Saltoposuchus''

In 1988, just four years after it was named, palaeontologistsMichael Benton

Michael James Benton (born 8 April 1956) is a British palaeontologist, and professor of vertebrate paleontology, vertebrate palaeontology in the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol. His published work has mostly concentrated on ...

and James Clark first formally proposed that specimens of ''Terrestrisuchus'' in fact represented the juveniles of ''Saltoposuchus'' and so was a junior synonym

In taxonomy, the scientific classification of living organisms, a synonym is an alternative scientific name for the accepted scientific name of a taxon. The botanical and zoological codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

...

of the latter. The similarity between ''Terrestrisuchus'' and ''Saltoposuchus'' had been identified since its description, and Crush had erected the family Saltoposuchidae in recognition of this. However, Benton and Clark considered that the characters Crush identified to separate the two taxa as invalid, and so that the two were likely to belong to be at least of the same genus. This hypothesis was rejected by Sereno and Wild in 1992, who claimed to have identified additional differences between the two genera, although Clark ''et al.'' (2001) considered these differences to be dubious or due to the size difference between their remains. In 2003, palaeontologist David Allen identified juvenile features in ''Terrestrisuchus'', and believed all the differing traits between it and ''Saltoposuchus'' to be ontogenetically variable, and so were otherwise indistinguishable. However, Allen ultimately rescinded this view and came to reject their synonymy in his unpublished Ph.D. thesis on the anatomy of ''Terrestrisuchus'' in 2010.

A formal re-evaluation of the hypothesis in 2013 concluded that the available evidence was not consistent with the two species being synonymous, and that it is likely that ''Terrestrisuchus'' is indeed its own genus. This included the non-overlapping geographic and stratigraphic ranges of the two taxa, with ''Terrestrisuchus'' being at least "several million years" younger than ''Saltoposuchus'', as well as inconsistencies in the patterns of the fusion of their vertebrae and the proportions of the hind limb during growth compared to other crocodylomorph growth series. ''Saltoposuchus'' itself was thoroughly redescribed in 2023 by Stephan Spiekman, who identified numerous morphological differences that could not be attributed to ontogeny or to individual variation, and so rejected their synonymy. The two taxa are nonetheless close relatives, comprising the clade Saltoposuchidae together with ''Litargosuchus''.

Palaeobiology

The thin, serrated teeth of ''Terrestrisuchus'' indicate that it was carnivorous, and like other early crocodylomorphs it was likely a generalist pursuit hunter that preyed upon small to mid-sized prey items. The shape and construction of its hip bones, particularly the elongated pubis, indicate that they were rigidly sutured together and that its pubis was not mobile as it is in modern crocodilians. This indicates that ''Terrestrisuchus'' would not have utilised the

The thin, serrated teeth of ''Terrestrisuchus'' indicate that it was carnivorous, and like other early crocodylomorphs it was likely a generalist pursuit hunter that preyed upon small to mid-sized prey items. The shape and construction of its hip bones, particularly the elongated pubis, indicate that they were rigidly sutured together and that its pubis was not mobile as it is in modern crocodilians. This indicates that ''Terrestrisuchus'' would not have utilised the hepatic piston

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocephalia. About 12,000 living speci ...

method of breathing found in modern crocodilians.

Metabolism and growth

The microstructure of the limb bones of ''Terrestrisuchus'' show that it was wellvascular Vascular can refer to:

* blood vessels, the vascular system in animals

* vascular tissue

Vascular tissue is a complex transporting tissue, formed of more than one cell type, found in vascular plants. The primary components of vascular tissue ...

ised and contained large amounts of energy-consuming fibrolamellar bone tissue, indicating a relatively fast growth-rate for ''Terrestrisuchus'' compared to other archosauriforms and even other pseudosuchians. Such a high growth rate is in agreement with an elevated, "warm-blooded" metabolism. However, the related "sphenosuchian" ''Hesperosuchus

''Hesperosuchus'' is an extinct genus of crocodylomorph reptile that contains a single species, ''Hesperosuchus agilis''. Remains of this pseudosuchian have been found in Late Triassic (Carnian) strata from Arizona and New Mexico.Colbert, E. H. 1 ...

'' was found to have a slower, more typical crocodilian-like growth rate, and so it is possible that the high growth rate of ''Terrestrisuchus'' was due to the sampled specimens being immature and still rapidly growing, and that adults had a slower metabolism.

Palaeoecology

''Terrestrisuchus'' was a coastal species, unusual for basal crocodylomorphs, which are typically known from inland floodplain environments. In the Late Triassic, the Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry and other quarries were part of ancient islands in a palaeo-archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

that stretched across southern Wales and England to Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

. The islands were forested karst

Karst () is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble carbonate rocks such as limestone and Dolomite (rock), dolomite. It is characterized by features like poljes above and drainage systems with sinkholes and caves underground. Ther ...

ic environments, riddled with fissures, sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are also known as shakeholes, and to openings where surface water ...

s and cavern

Caves or caverns are natural voids under the Earth's surface. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. Exogene caves are smaller openings that extend a relatively short distance underground (such as rock sh ...

s eroded into the limestone, environments which long limbed, agile reptiles like ''Terrestrisuchus'' may have been well suited to inhabit.

On the Pant-y-ffynnon palaeo-island, ''Terrestrisuchus'' coexisted with other archosaurs such as the similarly long-legged, enigmatic pseudosuchian ''Aenigmaspina

''Aenigmaspina'' (from Latin ''aenigma'' and ''spina'', meaning "enigmatic spine") is an extinct genus of enigmatic pseudosuchian (= crurotarsan) archosaur from the Late Triassic of the United Kingdom. Its fossils are known from the Pant-y-ffynno ...

'', the herbivorous sauropodomorph

Sauropodomorpha ( ; from Greek, meaning "lizard-footed forms") is an extinct clade of long-necked, herbivorous, saurischian dinosaurs that includes the sauropods and their ancestral relatives. Sauropods generally grew to very large sizes, had lo ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

''Pantydraco

''Pantydraco'' (where "panty-" is short for Pant-y-ffynnon, signifying ''hollow of the spring/well'' in Welsh, referring to the quarry at Bonvilston in South Wales where it was found) is a genus of basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Late T ...

'', and the coelophysoid

Coelophysoidea is an extinct clade of theropod dinosaurs common during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. They were widespread geographically, probably living on all continents. Coelophysoids were all slender, carnivorous forms with a ...

theropod

Theropoda (; from ancient Greek , (''therion'') "wild beast"; , (''pous, podos'') "foot"">wiktionary:ποδός"> (''pous, podos'') "foot" is one of the three major groups (clades) of dinosaurs, alongside Ornithischia and Sauropodom ...

''Pendraig

''Pendraig'' (meaning "chief dragon" in Middle Welsh) is a genus of coelophysoid theropod dinosaur from South Wales. It contains one species, ''Pendraig milnerae'', named after Angela Milner. The specimen was discovered in the Pant-y-Ffynnon Quarr ...

''. Rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a speciose g ...

ns (relatives of modern tuatara

The tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') is a species of reptile endemic to New Zealand. Despite its close resemblance to lizards, it is actually the only extant member of a distinct lineage, the previously highly diverse order Rhynchocephal ...

s) were very abundant and are known from at least three species including '' Clevosaurus cambrica'', ''Diphydontosaurus

''Diphydontosaurus'' is an extinct genus of small Rhynchocephalia, rhynchocephalian reptile from the Late Triassic of Europe. It is the most primitive known member of Sphenodontia.

Description

''Diphydontosaurus'' was one of the smallest spheno ...

'' and at least one or two unnamed species, which likely formed a large part of the diet of ''Terrestrisuchus'' (possibly evidenced by bite marks on the bones of ''Clevosaurus'' that likely belong to ''Terrestrisuchus''). ''Terrestrisuchus'' was a relatively rare component of the island's fauna, an expected relationship for a predatory animal.

Notes

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q981048 Terrestrial crocodylomorphs Triassic crocodylomorpha Rhaetian life Late Triassic reptiles of Europe Triassic England Triassic Wales Fossils of England Fossils of Wales Fossil taxa described in 1984 Prehistoric pseudosuchian genera