Taras Bulba (ballet) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Taras Bulba'' () is a romanticized historical

Taras Bulba's two sons, Ostap and Andriy, return home from an

Taras Bulba's two sons, Ostap and Andriy, return home from an

"THE CRYSTALLIZATION OF ETHNIC IDENTITY IN THE PROCESS OF MASS ETHNOPHOBIAS IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. (The Second Half of the 19th Century)." CRN E-book

/ref> It was in this particular context that many of Russia's literary works and popular media of the time became hostile toward the Poles in accordance with the state policy, Wasilij Szczukin

"Polska i Polacy w literaturze rosyjskiej. Literatura przedmiotu."

Uniwersytet Jagielloński,

"The Crystallization of Ethnic Identity..."

ACLS American Council of Learned Societies,

''The enemy with a thousand faces: the tradition of the other in western political thought and history.''

1989, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, 218 pages, Inadvertently, Gogol's accomplishment became "an anti-Polish novel of high literary merit, to say nothing about lesser writers."

Music

* The story was the basis of an opera, ''

Music

* The story was the basis of an opera, ''

Тарас Бульба Online text

(Russian) from public-library.ru

(Russian) from public-library.ru * *

Taras Bulba 2008 theatrical trailer

novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the Grotesque#In literature, grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works "The Nose (Gogol short story), ...

(1809–1852). It features the elderly Zaporozhian Cossack

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossac ...

Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at the Kiev Academy and then return home, whereupon the three men set out on a journey to the Zaporizhian Sich

The Zaporozhian Sich (, , ; also ) was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Zaporozhian Cossacks that existed between the 16th to 18th centuries, for the latter part of that period as an autonomous stratocratic state within the Cossa ...

(the Zaporizhian Cossack headquarters, located in southern Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

) where they join other Cossacks and go to war

"Go to War" is a song by American rock band Nothing More. It was released on June 23, 2017 as the first single off of the band's fifth album '' The Stories We Tell Ourselves.'' The song performed well commercially and critically, topping the ''Bi ...

against Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

.

The story was initially published in 1835 as part of the ''Mirgorod'' collection of short stories, but a much expanded version appeared in 1842 with some differences in the storyline. The twentieth-century critic described the 1842 text as a "paragon of civic virtue and a force of patriotic edification", contrasting it with the rhetoric of the 1835 version with its "distinctly Cossack jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

".

Inspiration

The character of Taras Bulba, the main hero of this novel, is a composite of several historical personalities. It might be based on the real family history of an ancestor ofNicholas Miklouho-Maclay

Nicholai Nikolaevich Miklouho-Maclay (; 1846 – 1888) was a Russian explorer of Ukrainian origin. He worked as an ethnologist, anthropologist and biologist who became famous as one of the earliest scientists to settle among and study indigen ...

, Cossack Ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

Okhrim Makukha from Starodub

Starodub (, , ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town in Bryansk Oblast, Russia, on the Babinets (river), Babinets River in the Dnieper basin, southwest of Bryansk. Population: 16,000 (1975).

History

Starodub has been known ...

, who killed his son Nazar for switching to the Polish side in treason, during the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

. Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay's uncle, Grigory Illich Miklouho-Maclay, studied together with Gogol in Nizhyn

Nizhyn (, ; ) is a city located in Chernihiv Oblast of northern Ukraine along the Oster River. The city is located north-east of the national capital Kyiv. Nizhyn serves as the capital city, administrative center of Nizhyn Raion. It hosts the ...

Gymnasium (officially Prince Bezborodko's Gymnasium of Higher Learning, today Nizhyn Gogol State University

The Nizhyn Gogol State University () is an academic state-sponsored university in Ukraine, located in Nizhyn, Chernihiv Oblast. It is one of the oldest institutions of higher education in Ukraine. It was originally established as the Nizhyn Lyc ...

) and probably told the family legend to Gogol. Another possible inspiration was the hero of the folk song "The deeds of Sava Chaly", published by Mykhailo Maksymovych

Mykhailo Oleksandrovych Maksymovych (; 3 September 1804 – 10 November 1873) was a professor in plant biology, Ukrainian historian and writer in the Russian Empire of a Cossack background.

He contributed to the life sciences, especially botany ...

, about Cossack captain Sava Chaly (executed in 1741 after serving as a colonel in the private army of a Polish noble), whose killing was ordered by his own father for betraying the Ukrainian cause.

Plot

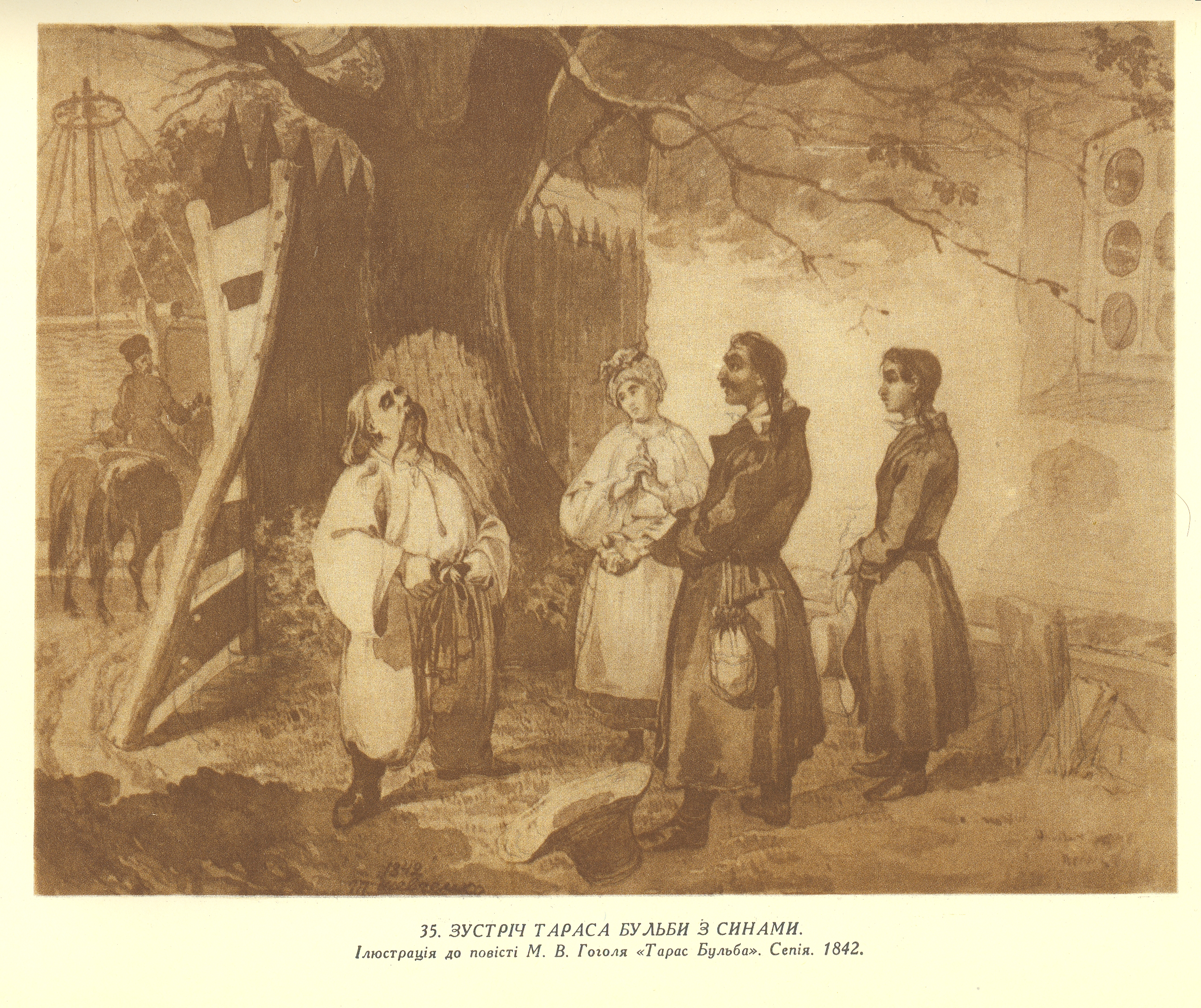

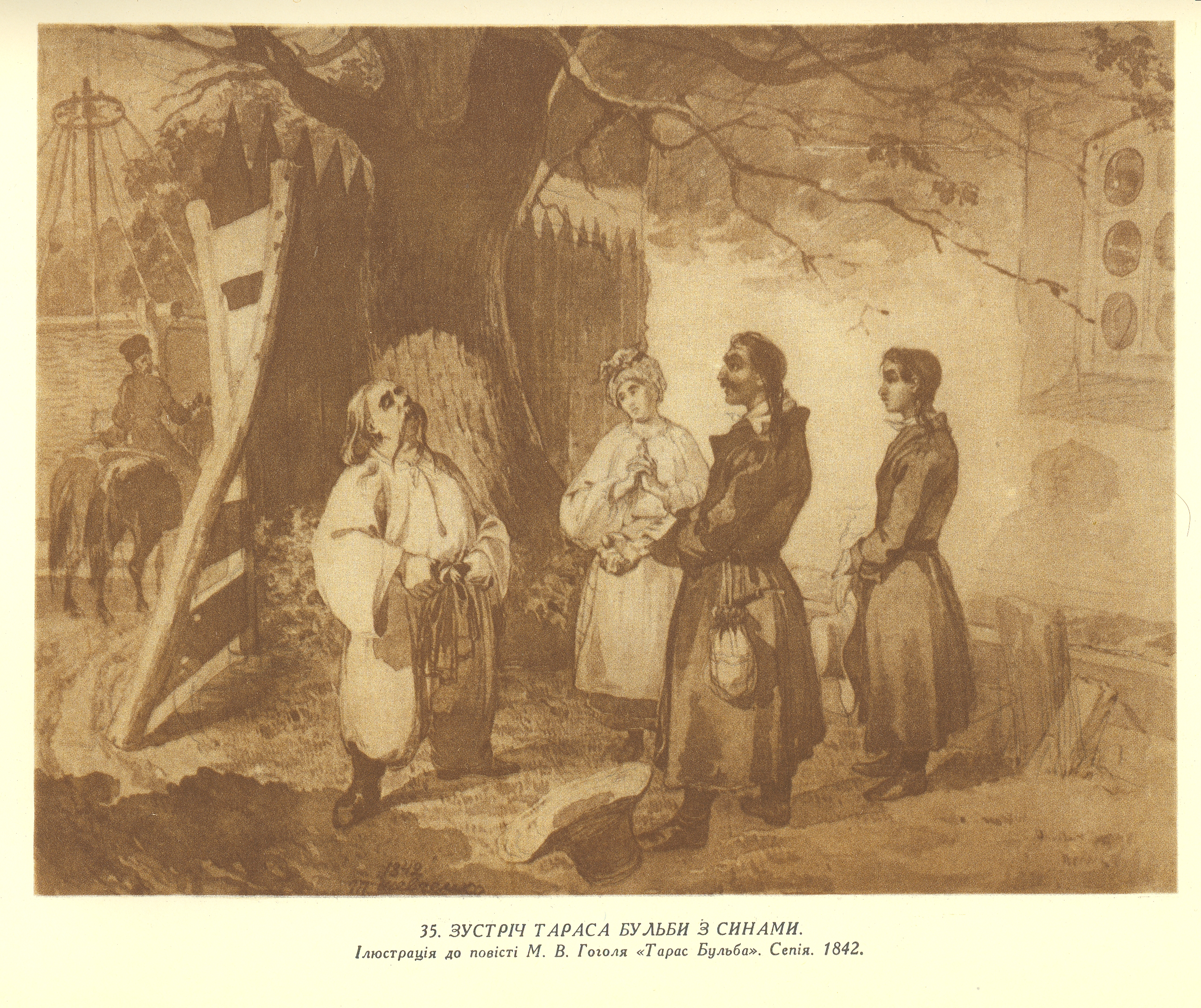

1842 revised edition

Taras Bulba's two sons, Ostap and Andriy, return home from an

Taras Bulba's two sons, Ostap and Andriy, return home from an Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

seminary in Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

. Ostap is the more adventurous, whereas Andriy has deeply romantic feelings of an introvert. While in Kiev, he fell in love with a young Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

noble girl, the daughter of the Voivode

Voivode ( ), also spelled voivod, voievod or voevod and also known as vaivode ( ), voivoda, vojvoda, vaivada or wojewoda, is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe in use since the Early Mid ...

of Kowno

Kaunas (; ) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius, the fourth largest List of cities in the Baltic states by population, city in the Baltic States and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaun ...

, but after a couple of meetings (edging into her house and in church), he stopped seeing her when her family returned home. Taras Bulba gives his sons the opportunity to go to war. They reach the Cossack camp at the Zaporozhian Sich

The Zaporozhian Sich (, , ; also ) was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Zaporozhian Cossacks that existed between the 16th to 18th centuries, for the latter part of that period as an autonomous stratocratic state within the Cossa ...

, where there is much merrymaking. Taras attempts to rouse the Cossacks to go into battle. He rallies them to replace the existing Hetman

''Hetman'' is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders (comparable to a field marshal or imperial marshal in the Holy Roman Empire). First used by the Czechs in Bohemia in the 15th century, ...

when the Hetman is reluctant to break the peace treaty.

They soon have the opportunity to fight the Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

, who rule all Ukraine west of the Dnieper River

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

. The Poles, led by their ultra-Catholic king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

, are accused of atrocities against Orthodox Christians, in which they are aided by Jews. After killing many of the Jewish merchants at the Sich, the Cossacks set off on a campaign against the Poles. They besiege Dubno Castle

The Dubno Castle (; ) was founded in 1492 by Prince Konstantin Ostrogski on a promontory overlooking the Ikva River not far from the ancient Ruthenian fort of Dubno, Volhynia.

Ostrogski castle was rebuilt in stone in the early 16th century und ...

where, surrounded by the Cossacks and short of supplies, the inhabitants begin to starve. One night a Tatar

Tatar may refer to:

Peoples

* Tatars, an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar"

* Volga Tatars, a people from the Volga-Ural region of western Russia

* Crimean Tatars, a people from the Crimea peninsula by the B ...

woman comes to Andriy and rouses him. He finds her face familiar and then recalls she is the servant of the Polish girl he was in love with. She advises him that all are starving inside the walls. He accompanies her through a secret passage starting in the marsh that goes into the monastery inside the city walls. Andriy brings loaves of bread with him for the starving girl and her mother. He is horrified by what he sees and in a fury of love, forsakes his heritage for the Polish girl.

Meanwhile, several companies of Polish soldiers march into Dubno to relieve the siege, and destroy a regiment of Cossacks. A number of battles ensue. Taras learns of his son's betrayal from Yankel the Jew, whom he saved earlier in the story. During one of the final battles, he sees Andriy riding in Polish garb from the castle and has his men draw him to the woods, where he takes him off his horse. Taras bitterly scolds his son, telling him "I gave you life, I will take it", and shoots him dead.

Taras and Ostap continue fighting the Poles. Ostap is captured while his father is knocked out. When Taras regains consciousness he learns that his son was taken prisoner by the Poles. Yankel agrees to take Taras to Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, where Ostap is held captive, hiding Taras in a cartload of bricks. Once in Warsaw, a group of Jews help Yankel dress Taras as a German count. They go into the prison to see Ostap, but Taras unwittingly reveals himself as a Cossack, and only escapes by use of a great bribe. Instead, they attend the execution the following day. During the execution, Ostap does not make a single sound, even while being broken on the wheel

The breaking wheel, also known as the execution wheel, the Wheel of Catherine or the (Saint) Catherine('s) Wheel, was a Torture, torture method used for Capital punishment#Public execution, public execution primarily in Europe from Classical ant ...

, but, disheartened as he nears death, he calls aloud on his father, unaware of his presence. Taras answers him from the crowd, thus giving himself away, but manages to escape.

Taras returns home to find all of his old Cossack friends dead and younger Cossacks in their place. He goes to war again. The new Hetman wishes to make peace with the Poles, which Taras is strongly against, warning that the Poles are treacherous and will not honour their words. Failing to convince the Hetman, Taras takes his regiment away to continue the assault independently. As Taras predicted, once the new Hetman agrees to a truce, the Poles betray him and kill a number of Cossacks. Taras and his men continue to fight and are finally caught in a ruined fortress, where they battle until the last man is defeated.

Taras is nailed and tied to a tree and set aflame. Even in this state, he calls out to his men to continue the fight, claiming that a new Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

is coming who will rule the earth. The story ends with Cossacks on the Dniester River

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

recalling the great feats of Taras and his unwavering Cossack spirit.

Differences from 1835 edition

For reasons that are currently disputed, the 1842 edition was expanded by three chapters and included Russian nationalist themes. Potential reasons include a necessity to stay in line with the official tsarist ideology, as well as the author's changing political and aesthetic views (later manifested in ''Dead Souls

''Dead Souls'' ( , pre-reform spelling: ) is a novel by Nikolai Gogol, first published in 1842, and widely regarded as an exemplar of 19th-century Russian literature. The novel chronicles the travels and adventures of Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov ...

'' and ''Selected Passages from Correspondence with his Friends''). The changes included three new chapters and a new ending (in the 1835 edition, the protagonist is not burned at the stake by the Poles).

Ethnic depictions

Depiction of Jews

Felix Dreizin and David Guaspari in their ''The Russian Soul and the Jew: Essays in Literary Ethnocentrism'' discussanti-Semitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

, pointing out Gogol's attachment to "anti-Jewish prejudices prevalent in Russian and Ukrainian culture". In Léon Poliakov

Léon Poliakov (; 25 November 1910 – 8 December 1997) was a French historian who wrote extensively on the Holocaust and antisemitism. He is the author of ''The Aryan Myth''.

Biography

Born into a Russian Jewish family, Poliakov lived in Italy ...

's ''The History of Antisemitism'', the author states that "The 'Yankel' from ''Taras Bulba'' indeed became the archetypal

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, History of psychology#Emergence of German experimental psychology, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a stat ...

Jew in Russian literature. Gogol painted him as supremely exploitative, cowardly, and repulsive, albeit capable of gratitude". There is a scene in ''Taras Bulba'' where Jews are thrown into a river, a scene where Taras Bulba visits the Jews and seeks their aid, and reference by the narrator of the story that Jews are treated inhumanely.Mirogorod: Four Tales by N. Gogol, page 89, trans. by David Magarshack. Minerva Press 1962

Depiction of Poles

Following the 1830–1831 November Uprising against the Russian imperial rule in the heartland of Poland – partitioned since 1795 – the Polish people became the subject of an official campaign of discrimination by the Tsarist authorities. "Practically all of the Russian government, bureaucracy, and society were united in one outburst against the Poles. The phobia that gripped society gave a new powerful push to the Russian national solidarity movement" – wrote historianLiudmila Gatagova Liudmila Sultanovna Gatagova () is a Russian historian, essayist, and the Research Fellow at the Institute of History of the Russian Academy of Sciences of Ossetian descent, specializing in international relations and history of the Russian Empire ...

.Liudmila Gatagova Liudmila Sultanovna Gatagova () is a Russian historian, essayist, and the Research Fellow at the Institute of History of the Russian Academy of Sciences of Ossetian descent, specializing in international relations and history of the Russian Empire ...

"THE CRYSTALLIZATION OF ETHNIC IDENTITY IN THE PROCESS OF MASS ETHNOPHOBIAS IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. (The Second Half of the 19th Century)." CRN E-book

/ref> It was in this particular context that many of Russia's literary works and popular media of the time became hostile toward the Poles in accordance with the state policy, Wasilij Szczukin

"Polska i Polacy w literaturze rosyjskiej. Literatura przedmiotu."

Uniwersytet Jagielloński,

Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

. ''See comments by Szczukin to section on literature in the Russian language:'' "Literatura w języku rosyjskim," pp. 14–22. especially after the emergence of the Panslavist ideology, accusing them of betraying the "Slavic family".Liudmila Gatagova Liudmila Sultanovna Gatagova () is a Russian historian, essayist, and the Research Fellow at the Institute of History of the Russian Academy of Sciences of Ossetian descent, specializing in international relations and history of the Russian Empire ...

"The Crystallization of Ethnic Identity..."

ACLS American Council of Learned Societies,

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

According to sociologist and historian Prof. Vilho Harle, ''Taras Bulba'', published only four years after the rebellion, was a part of this anti-Polish propaganda effort. Vilho Harle''The enemy with a thousand faces: the tradition of the other in western political thought and history.''

1989, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, 218 pages, Inadvertently, Gogol's accomplishment became "an anti-Polish novel of high literary merit, to say nothing about lesser writers."

Depiction of Turks

As in other Russian novels of the era,Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Turkey

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic lang ...

are treated as barbaric and uncivilized compared to Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common ancestry, language, faith, historical continuity, etc. There are ...

because of their nomadic nature.

Adaptations

Music

* The story was the basis of an opera, ''

Music

* The story was the basis of an opera, ''Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at th ...

'', written between 1880-1891, by Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko

Mykola Vitaliiovych Lysenko (; 22 March 1842 – 6 November 1912) was a Ukrainian composer, pianist, conductor and ethnomusicologist of the late Romantic period. In his time he was the central figure of Ukrainian music, with an ''oeuvre'' tha ...

. It was published in 1913, and first performed in 1924 (12 years after the composer's death). The opera's libretto was written by Mykhailo Starytsky

Mykhailo Petrovych Starytsky (; 14 December 1840 – 27 April 1904), in English Michael Starycky, was a Ukrainian writer, poet, and playwright.

Biography

He was born in a family of retired cavalry officers (Rittmeister) Petro Starytsky and ...

, the composer's cousin. Tchaikovsky had been impressed with it, and wanted to stage it in Moscow, but Lysenko insisted that it be performed in Ukrainian (not translated into Russian), so Tchaikovsky wasn't able to get it staged in Moscow.

* Czech composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

Leoš Janáček

Leoš Janáček (, 3 July 1854 – 12 August 1928) was a Czech composer, Music theory, music theorist, Folkloristics, folklorist, publicist, and teacher. He was inspired by Moravian folk music, Moravian and other Slavs, Slavic music, includin ...

's ''Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at th ...

'', a symphonic rhapsody for orchestra, was written in the years 1915–1918, inspired in part by the mass slaughter of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The composition was first performed on 9 October 1921 by František Neumann

František Neumann (16 June 187425 February 1929) was a Czech conductor and composer. He was particularly associated with the National Theatre in Brno, and the composer Leoš Janáček, the premieres of many of whose operas he conducted.

Biograp ...

, and in Prague on 9 November 1924 by Václav Talich

Václav Talich (; 28 May 1883, Kroměříž – 16 March 1961, Beroun) was a Czech conductor, violinist and later a musical pedagogue. He is remembered today as one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century, the object of countless reissue ...

and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

The Czech Philharmonic () is a symphony orchestra based in Prague. Its principal performing venue is the Rudolfinum concert hall.

History

The name "Czech Philharmonic Orchestra" appeared for the first time in 1894, as the title of the orche ...

.

* Reinhold Glière

Reinhold Moritzevich Glière (23 June 1956), born Reinhold Ernest Glier, was a Russian and Soviet composer of German and Polish descent. He was awarded the title of People's Artist of RSFSR (1935) and People's Artist of USSR (1938).

Biography ...

wrote a ballet in Four Acts in 1951-52, published as Opus 92, to commemorate the centenary of the death of Gogol. The ballet was one of Glière's last completed works. It was first performed and published in 1952.

* Franz Waxman

Franz Waxman (né Wachsmann; December 24, 1906February 24, 1967) was a German-born composer and conductor of Jewish descent, known primarily for his work in the film music genre. His film scores include ''Bride of Frankenstein'', ''Rebecca (194 ...

wrote an Oscar-nominated score for the 1962 film ''Taras Bulba''.

Film

* ''Taras Bulba'' (1909), a silent film adaptation, directed by Aleksandr Drankov

Alexander Osipovich Drankov (; 1879–1949) was a Russian and Soviet photographer, cameraman, film director, and film producer. He is considered a pioneer of Russian pre-revolutionary cinematography.

Biography

Drankov was born Abram Iosifovich Dr ...

* ''Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at th ...

'' (1924), made in Germany by the Russian exile Joseph N. Ermolieff

* ''Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at th ...

'' (1936), a French production, directed by Russian director Alexis Granovsky, with noted decor by Andrei Andreyev

* ''The Rebel Son

''The Rebel Son'' is a 1938 British historical adventure film directed by Adrian Brunel and starring Harry Baur, Anthony Bushell and Roger Livesey. Patricia Roc also appears in her first screen role. It is a re-working by Alexander Korda of Gran ...

'' (1938), a British film starring Harry Baur with a supporting cast of significant British actors

* ''Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at th ...

'' (1962), an American adaption starring Yul Brynner

Yuliy Borisovich Briner (; July 11, 1920 – October 10, 1985), known professionally as Yul Brynner (), was a Russian-born actor. He was known for his portrayal of King Mongkut in the Rodgers and Hammerstein stage musical ''The King and I'' (19 ...

and Tony Curtis

Tony Curtis (born Bernard Schwartz; June 3, 1925September 29, 2010) was an American actor with a career that spanned six decades, achieving the height of his popularity in the 1950s and early 1960s. He acted in more than 100 films, in roles co ...

and directed by J. Lee Thompson

John Lee Thompson (1 August 1914 – 30 August 2002) was an English film director, screenwriter and producer. Initially an exponent of social realism, he became known as a versatile and prolific director of thrillers, action, and adventure fil ...

; this adaptation featured a significant musical score by Franz Waxman

Franz Waxman (né Wachsmann; December 24, 1906February 24, 1967) was a German-born composer and conductor of Jewish descent, known primarily for his work in the film music genre. His film scores include ''Bride of Frankenstein'', ''Rebecca (194 ...

, which received an Academy Award nomination. Bernard Herrmann

Bernard Herrmann (born Maximillian Herman; June 29, 1911December 24, 1975) was an American composer and conductor best known for his work in film scoring. As a conductor, he championed the music of lesser-known composers. He is widely regarde ...

called it "the score of a lifetime".

* '' Taras Bulba, the Cossack'', a 1962 Italian film version

* ''Taras Bulba

''Taras Bulba'' (; ) is a romanticized historical novella set in the first half of the 17th century, written by Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852). It features elderly Zaporozhian Cossack Taras Bulba and his sons Andriy and Ostap. The sons study at th ...

'' (2009), directed by Vladimir Bortko

Vladimir Vladimirovich Bortko (; born 7 May 1946) is a Russian film director, screenwriter, producer and politician. He was a member of the State Duma between 2011 and 2021, and was awarded the title of People's Artist of Russia.

Biography

Bort ...

, commissioned by the Russian state TV and paid for totally by the Russian Ministry of Culture. It includes Ukrainian, Russian and Polish actors such as Bohdan Stupka

Bohdan Sylvestrovych Stupka (; 27 August 1941 – 22 July 2012) was a Ukrainian actor and minister of culture of Ukraine. He was born in Kulykiv, General Government to Ukrainian parents. In 2001, he was a member of the jury at the 23rd Moscow I ...

(as Taras Bulba), Ada Rogovtseva

Ada Mykolaivna Rohovtseva (; born 16 July 1937) is a Ukrainian and former Soviet stage and film actress. She has appeared in over 30 films and television shows since 1957. Professor at the National University of Culture. She won the award for Be ...

(as Taras Bulba's wife), Igor Petrenko

Igor Petrovich Petrenko (; born August 23, 1977) is a Russian actor of cinema and theater. In 2002 President of Russia, Vladimir Putin gave him State Prize of the Russian Federation, The State prize of Russia.

Biography

Igor Petrenko was born ...

(as Andriy Bulba), Vladimir Vdovichenkov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Vdovichenkov (; born 13 August 1971) is a Russian theater and screen actor known for his roles in ''Brigada'' (2002), ''Leviathan'' (2014), '' Bummer'' (2003) and Salyut 7 (2017).

Early life and education

Vdovichenkov was ...

(as Ostap Bulba) and Magdalena Mielcarz

Magdalena Mielcarz (born 3 March 1978) is a Polish actress, model and singer also known as Lvma Black.

Career

As a model, she appeared on numerous covers of magazines like ''Elle (magazine), Elle'', ''Cosmopolitan (magazine), Cosmopolitan'', ' ...

(as a Polish noble girl). The movie was filmed at several locations in Ukraine such as Zaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia ...

, Khotyn

Khotyn (, ; , ; see #Name, other names) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city in Dnistrovskyi Raion, Chernivtsi Oblast of western Ukraine, located south-west of Kamianets-Podilskyi. It hosts the administration of Khotyn urban hromada, one of th ...

and Kamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi (, ; ) is a city on the Smotrych River in western Ukraine, western Ukraine, to the north-east of Chernivtsi. Formerly the administrative center of Khmelnytskyi Oblast, the city is now the administrative center of Kamianets ...

during 2007. The screenplay used the 1842 edition of the novel.

*' (2009), a Ukrainian film.

*''Veer

The Veer is an option running play often associated with option offenses in American football, made famous at the College football, collegiate level by Bill Yeoman's Houston Cougars football, Houston Cougars. It is currently run primarily at Hi ...

'' (2010), a Hindi movie set in 19th century India, is based in part on the plot of ''Taras Bulba''.

In popular culture

* An Australian racehorse of the 1970s was named Taras Bulba. From 40 starts he had 12 wins, including the 1974Australian Derby

The Australian Derby is an Australian Turf Club Group 1 Thoroughbred horse race for three-year-olds at set weights held at Randwick Racecourse, Sydney, Australia in April, during the Autumn ATC Championships Carnival. The race is considered to b ...

and won $335,000 in prize money.

* The 2007 Jane Smiley

Jane Smiley (born September 26, 1949) is an American novelist. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1992 for her novel ''A Thousand Acres'' (1991).

Biography

Born in Los Angeles, California, Smiley grew up in Webster Groves, Missouri, a subu ...

book ''Ten Days in the Hills'' features a film producer trying to film a new version of ''Taras Bulba''.

* The villainous character Taurus Bulba (an anthropomorphic bull) in the Disney cartoon show ''Darkwing Duck

''Darkwing Duck'' is an American animated superhero comedy television series produced by Disney Television Animation (formerly Walt Disney Television Animation) that first ran from 1991 to 1992 on both the syndicated programming block '' The Dis ...

'' is a nod, if in name only, to the literary character of Taras Bulba.

* In the 2002 video game '' No One Lives Forever 2: A Spy in H.A.R.M.'s Way'', Cate Archer

Catherine Ann "Cate" Archer, codenamed The Fox, is a player character and the protagonist in the ''No One Lives Forever'' video game series by Monolith Productions. Cate, a covert operative for British-based counter-terrorism organization UNITY ...

(controlled by the player) finds a copy of Taras Bulba by Nikolai Gogol when searching a vanquished foe.

* In 2007, a copy of the book is part of the literature selected by Christopher McCandless

Christopher Johnson McCandless (; February 12, 1968 – August 1992), also known by his pseudonym "Alexander Supertramp", was an American adventurer who sought an increasingly nomadic lifestyle as he grew up.

After graduating from Emory Univer ...

in the movie '' Into the Wild'' among other similar works of authors such as Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

, Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

and Jack London

John Griffith London (; January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors t ...

.

References and notes

External links

*Тарас Бульба Online text

(Russian) from public-library.ru

(Russian) from public-library.ru * *

Taras Bulba 2008 theatrical trailer

See also

With Fire and Sword

''By Fire and Sword'' () is a historical novel by the Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz, published in 1884. It is the first volume of a series known to Poles as The Trilogy, followed by '' The Deluge'' (''Potop'', 1886) and '' Fire in the Step ...

by Henryk Sienkiewicz

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz ( , ; 5 May 1846 – 15 November 1916), also known by the pseudonym Litwos (), was a Polish epic writer. He is remembered for his historical novels, such as The Trilogy, the Trilogy series and especially ...

{{Authority control

Novels by Nikolai Gogol

Historical novels

1835 Russian novels

Fictional Cossacks

Anti-Catholic publications

Antisemitism in literature

Race-related controversies in literature

Novels set in Ukraine

Short stories about Cossacks

Fiction about filicide

Russian novels adapted into films

Zaporozhian Host

Ukrainian novels adapted into films

Epic novels