Sviatoslav Richter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

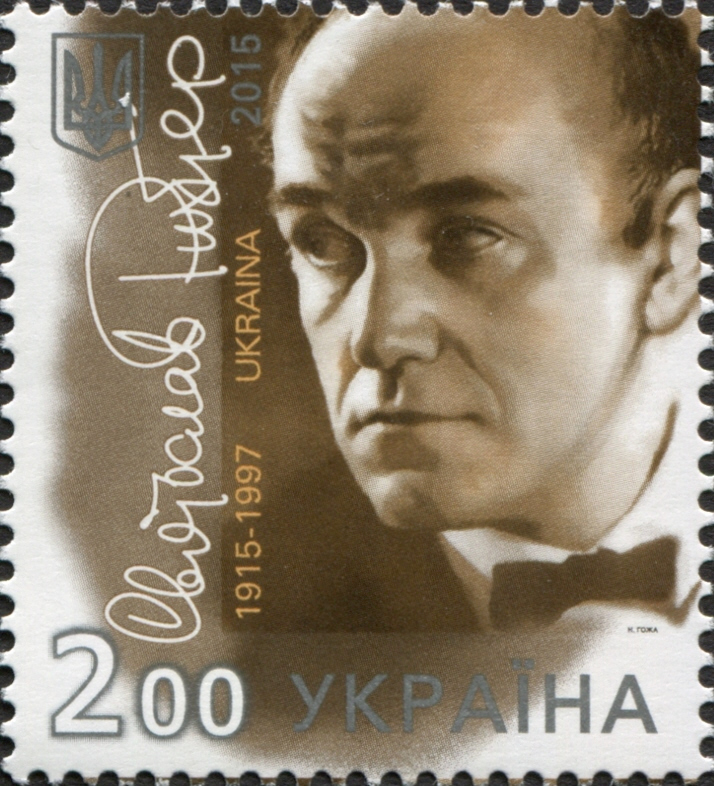

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter ( – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet and Russian classical

Richter was born in

Richter was born in

In 1948, Richter and Dorliak gave recitals in

In 1948, Richter and Dorliak gave recitals in

The Italian critic Piero Rattalino has asserted that the only pianists comparable to Richter in the history of piano performance were

The Italian critic Piero Rattalino has asserted that the only pianists comparable to Richter in the history of piano performance were

Richter International Piano Competition

Website dedicated to Sviatoslav Richter, includes an extensive discography

* ttp://www.neuhaus.it/english/dorliak.html Brief obituary of Nina Dorliak

Paul Geffen, 1999:

''Vita'' of Sviatoslav Richter

Pete Taylor, 2010:

Concert list program with Google Earth maps

Sviatoslav Richter's memorial website (in Russian)

Website of Memorial Richter's apartment

{{DEFAULTSORT:Richter, Sviatoslav 1915 births 1997 deaths Soviet composers Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery Classical piano duos Deutsche Grammophon artists Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Commandeurs of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres Glinka State Prize of the RSFSR winners Grammy Award winners Heroes of Socialist Labour Recipients of the Lenin Prize Moscow Conservatory alumni People's Artists of the USSR People's Artists of the RSFSR Musicians from Odesa Recipients of the Léonie Sonning Music Prize Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 3rd class Recipients of the Order of Lenin Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Russian classical pianists Male classical pianists Russian people of German descent Soviet classical pianists State Prize of the Russian Federation laureates Recipients of the Stalin Prize Ukrainian people of German descent Ukrainian people of Russian descent Music & Arts artists 20th-century Russian male musicians

pianist

A pianist ( , ) is a musician who plays the piano. A pianist's repertoire may include music from a diverse variety of styles, such as traditional classical music, jazz piano, jazz, blues piano, blues, and popular music, including rock music, ...

. He is regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time, Great Pianists of the 20th Century and has been praised for the "depth of his interpretations, his virtuoso technique, and his vast repertoire".

Biography

Childhood

Richter was born in

Richter was born in Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( ; see #Names, below for other names) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the Capital city, administrative center of Zhytomyr Oblast (Oblast, province), as well as the administrative center of the surrounding ...

, Volhynian Governorate

Volhynia Governorate, also known as Volyn Governorate, was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Southwestern Krai of the Russian Empire. It consisted of an area of and a population of 2,989,482 inhabitants. The governorate ...

, in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(modern-day Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

), the hometown of his parents. His father, (1872–1941), was a pianist, organist and composer born to German expatriates, who from 1893 to 1900 studied at the Vienna Conservatory. His mother, Anna Pavlovna Richter (née Moskaleva; 1893–1963), came from a noble Russian landowning family, and at one point had studied under her future husband. In 1918, when Richter's parents were in Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

, the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

separated them from their son, and Richter moved in with his aunt Tamara. He lived with her from 1918 to 1921, and it was then that his interest in art first manifested itself: he first became interested in painting

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

, which his aunt taught him.

In 1921 the family was reunited, and the Richters moved to Odessa, where Teofil taught at the Odessa Conservatory and, briefly, worked as organist of a Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

church. In the early 1920s Richter became interested in music (as well as other art forms such as cinema, literature, and theatre) and started studying piano. Unusually, he was largely self-taught. His father gave him only a basic education in music, as did one of his father's pupils, a Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

harpist.

Even at an early age, Richter was an excellent sight-reader and regularly practised with local opera and ballet companies. He developed a lifelong passion for opera, vocal and chamber music that found its full expression in the festivals he established in La Grange de Meslay, France, and in Moscow at the Pushkin Museum

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (, abbreviated as , ''GMII'') is the largest museum of European art in Moscow. It is located in Volkhonka street, just opposite the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. The International musical festival Sviatos ...

. At age 15, he started to work at the Odessa Opera, where he accompanied the rehearsals.

Early career

On March 19, 1934, Richter gave his first recital, at the Engineers' Club ofOdessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

; but he did not formally start studying piano until three years later, when he decided to seek out Heinrich Neuhaus, a pianist and piano teacher, at the Moscow Conservatory

The Moscow Conservatory, also officially Tchaikovsky Moscow State Conservatory () is a higher musical educational institution located in Moscow, Russia. It grants undergraduate and graduate degrees in musical performance and musical research. Th ...

. During Richter's audition for Neuhaus (at which he performed Chopin's Ballade No. 4), Neuhaus apparently whispered to a fellow student, "This man's a genius." Although Neuhaus taught many pianists, including Emil Gilels

Emil Grigoryevich Gilels (19 October 191614 October 1985, born Samuil) was a Soviet pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time. His sister Elizabeth, three years his junior, was a violinist. His daughter Elena ...

and Radu Lupu

Radu Lupu (30 November 1945 – 17 April 2022) was a Romanian pianist. He was widely recognized as one of the greatest pianists of his time.

Born in Galați, Romania, Lupu began studying piano at the age of six. Two of his major piano teache ...

, it is said that he considered Richter to be "the genius pupil, for whom he had been waiting all his life", while acknowledging that he taught Richter "almost nothing".

Early in his career, Richter also tried composition, and it even appears that he played some of his works during his audition for Neuhaus. He gave up composition shortly after moving to Moscow. Years later, Richter explained this decision as follows: "Perhaps the best way I can put it is that I see no point in adding to all the bad music in the world".

By the beginning of World War II, Richter's parents' marriage had failed and his mother had fallen in love with another man. Because Richter's father was a German, he was under suspicion by the authorities and a plan was made for the family to flee the country. Due to her romantic involvement, his mother did not want to leave and so they remained in Odessa. In August 1941, his father was arrested and later found guilty of espionage, being sentenced to death on October 6, 1941. Richter did not speak to his mother again until shortly before her death nearly 20 years later in connection with his first US tour.

In 1943, Richter met Nina Dorliak (1908–1998), an operatic soprano. He noticed Dorliak during the memorial service for Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko

Vladimir Ivanovich Nemirovich-Danchenko (; – 25 April 1943) was a Soviet and Russian theatre director, writer, pedagogue

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how t ...

, caught up with her at the street and suggested to accompany her in recital. It is often alleged that they married around this time, but in fact Dorliak only obtained a marriage certificate a few months after Richter's death in 1997. They remained living companions from around 1945 until Richter's death; they had no children. Dorliak accompanied Richter both in his complex private life and career. She supported him in his final illness, and died herself less than a year later, on May 17, 1998.

Since his death it has been suggested that Richter was homosexual and that having a female companion provided a social front for his true sexual orientation, because homosexuality was widely taboo at that time and could result in legal repercussions. Richter was an intensely private person and was usually quiet and withdrawn, and refused to give interviews. He never publicly discussed his personal life until the last year of his life when film-maker Bruno Monsaingeon convinced him to be interviewed for a documentary.

Rise to international profile

In 1949, Richter won the Stalin Prize, which led to extensive concert tours in Russia, Eastern Europe and China. He gave his first concerts outside the Soviet Union inCzechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

in 1950. In 1952, Richter was invited to play Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic music, Romantic period. With a diverse List of compositions by Franz Liszt, body of work spanning more than six ...

in a film based on the life of Mikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( rus, links=no, Михаил Иванович Глинка, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka, mʲɪxɐˈil ɨˈvanəvʲɪdʑ ˈɡlʲinkə, Ru-Mikhail-Ivanovich-Glinka.ogg; ) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognit ...

, called '' The Composer Glinka'' (remake

A remake is a film, television series, video game, song or similar form of entertainment that is based upon and retells the story of an earlier production in the same medium—e.g., a "new version of an existing film". A remake tells the same s ...

of the 1946 film ''Glinka''). The title role was played by Boris Smirnov.

On February 18, 1952, Richter made his sole appearance as a conductor in the world premiere of Prokofiev's Symphony-Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in E minor, with Mstislav Rostropovich

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich (27 March 192727 April 2007) was a Russian Cello, cellist and conducting, conductor. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was well known for both inspiring and commissioning new works, which enl ...

as the soloist.

In April 1958, Richter was on the jury of the first Tchaikovsky Competition

The International Tchaikovsky Competition is a classical music competition held every four years in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Russia, for pianists, violinists, and cellists between 16 and 32 years of age and singers between 19 and 32 years of ...

in Moscow. Watching Van Cliburn

Harvey Lavan "Van" Cliburn Jr. (July 12, 1934February 27, 2013) was an American pianist. At the age of 23, Cliburn achieved worldwide recognition when he won the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958 during the Cold ...

's performance of Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of ...

's Concerto No. 3, Richter wept with joy; he awarded Cliburn a 25, a perfect score.

In 1960, even though he had a reputation for being "indifferent" to politics, Richter defied the authorities when he performed at Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

's funeral.

Having received the Stalin and Lenin prizes and become People's Artist of the RSFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

, he gave his first tour concerts in the US in 1960, and in England and France in 1961.

Touring and recording

In 1948, Richter and Dorliak gave recitals in

In 1948, Richter and Dorliak gave recitals in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, then in 1950 performed in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

and Bratislava

Bratislava (German: ''Pressburg'', Hungarian: ''Pozsony'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the Slovakia, Slovak Republic and the fourth largest of all List of cities and towns on the river Danube, cities on the river Danube. ...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. In 1954, Richter gave recitals in Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

. In 1956, he again toured Czechoslovakia, then in 1957, he toured China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, then again performed in Prague, Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

, and Warsaw. In 1958, Richter recorded Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''. , group=n ( – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor who l ...

's 5th Piano Concerto with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Witold Rowicki – the recording which made Richter known in the United States. In 1959, Richter made another successful recording of Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of ...

's 2nd Piano Concerto with the Warsaw Philharmonic on Deutsche Grammophon

Deutsche Grammophon (; DGG) is a German classical music record label that was the precursor of the corporation PolyGram. Headquartered in Berlin Friedrichshain, it is now part of Universal Music Group (UMG) since its merger with the UMG family of ...

label. Thus the West first became aware of Richter through recordings made in the 1950s. One of Richter's first advocates in the West was Emil Gilels

Emil Grigoryevich Gilels (19 October 191614 October 1985, born Samuil) was a Soviet pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time. His sister Elizabeth, three years his junior, was a violinist. His daughter Elena ...

, who stated during his first tour of the United States that the critics (who were giving Gilels rave reviews) should "wait until you hear Richter."

Richter's first concerts in the West took place in May 1960, when he was allowed to play in Finland, and on October 15, 1960, in Chicago, where he played Brahms's 2nd Piano Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) is an American symphony orchestra based in Chicago, Illinois. Founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891, the ensemble has been based in the Symphony Center since 1904 and plays a summer season at the Ravinia F ...

and Erich Leinsdorf, creating a sensation. In a review, ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1847, it was formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper", a slogan from which its once integrated WGN (AM), WGN radio and ...

'' music critic Claudia Cassidy, who was known for her unkind reviews of established artists, recalled Richter first walking on stage hesitantly, looking vulnerable (as if about to be "devoured"), but then sitting at the piano and dispatching "the performance of a lifetime". Richter's 1960 tour of the United States culminated in a series of concerts at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhattan), 57t ...

.

Richter disliked performing in the United States. Following a 1970 incident at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhattan), 57t ...

in New York City, when Richter's performance alongside David Oistrakh

David Fyodorovich Oistrakh (; – 24 October 1974) was a Soviet Russian violinist, List of violists, violist, and Conducting, conductor. He was also Professor at the Moscow Conservatory, People's Artist of the USSR (1953), and Laureate of the ...

was disrupted by anti-Soviet protests, Richter vowed never to return. Rumours of a planned return to Carnegie Hall surfaced in the last years of Richter's life, although it is not clear whether there was any truth behind them.

In 1961, Richter played for the first time in London. His first recital, pairing works of Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( ; ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

and Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''. , group=n ( – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor who l ...

, was received with hostility by British critics. Neville Cardus

Sir John Frederick Neville Cardus, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (2 April 188828 February 1975) was an English writer and critic. From an impoverished home background, and mainly self-educated, he became ''The Manchester Gua ...

concluded that Richter's playing was "provincial", and wondered why Richter had been invited to play in London, given that London had plenty of "second class" pianists of its own. Following a July 18, 1961, concert, where Richter performed both of Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic period. With a diverse body of work spanning more than six decades, he is considered to be one of the most pro ...

's piano concertos, the critics reversed course.

In 1963, after searching in the Loire Valley, France, for a venue suitable for a music festival, Richter discovered La Grange de Meslay, several kilometres north of Tours. The festival was established by Richter and became an annual event.

In 1970, Richter visited Japan for the first time, travelling across Siberia by railway and ship as he disliked flying. He played Beethoven, Schumann, Mussorgsky, Prokofiev, Bartók and Rachmaninoff, as well as works by Mozart and Beethoven with Japanese orchestras. He visited Japan eight times.

Later years

While he very much enjoyed performing for an audience, Richter hated planning concerts years in advance, and in later life took to playing at very short notice in small, most often darkened halls, with only a small lamp lighting the score. Richter said that this setting helped the audience focus on the music being performed, rather than on extraneous and irrelevant matters such as the performer's grimaces and gestures.Death

Richter died at Central Clinical Hospital inMoscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

from a heart attack on August 1, 1997, aged 82. He had been suffering from depression due to an inability to perform caused by changes in his hearing that altered his perception of pitch.

Career

In 1981, Richter initiated the international December Nights music festival, held at thePushkin Museum

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (, abbreviated as , ''GMII'') is the largest museum of European art in Moscow. It is located in Volkhonka street, just opposite the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. The International musical festival Sviatos ...

, which after his death in 1997 was renamed ''December Nights of Sviatoslav Richter''.

In 1986, Richter embarked on a six-month tour of Siberia with his beloved Yamaha piano, giving perhaps 150 recitals, at times performing in small towns that did not even have a concert hall. It is said that after one such concert, the members of the audience, who had never before heard classical music performed, gathered in the middle of the hall and started swaying from side to side to celebrate the performer.

In his last years, Richter gave a few concerts for students that were free of charge (February 14, 1990: Teatro Romea, Murcia, Spain, also March 1, 1990: matinee concert in Teatre Municipal, Girona, Spain).

An anecdote illustrates Richter's approach to performance in the last decade of his life. After reading a biography of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

(he was an avid reader), Richter had his secretary send a telegram to the director of the theater in Aachen, Charlemagne's favoured residence city and his burial place, stating "The Maestro has read a biography of Charlemagne and would like to play at Aquisgrana (Aachen

Aachen is the List of cities in North Rhine-Westphalia by population, 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

Aachen is locat ...

)". The performance took place shortly thereafter.

As late as 1995, Richter continued to perform some of the most demanding pieces in the pianistic repertoire, including Ravel's ''Miroirs

file:Ravel Pierre Petit.jpg, upRavel in 1907

''Miroirs'' (, ) is a five-movement suite (music), suite for solo piano written by French composer Maurice Ravel between 1904 and 1905."Miroirs". Maurice Ravel Frontispice. First performed by Ricardo V ...

'' cycle, Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''. , group=n ( – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor who l ...

's Second Sonata and Chopin's études, Ballade No. 4, and Schumann

Robert Schumann (; ; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic music, Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber ...

's Toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virt ...

.

Richter's last recorded orchestral performance was of three Mozart concerti in 1994 with the Japan Shinsei Symphony Orchestra conducted by his old friend Rudolf Barshai.

Richter's last recital was a private gathering in Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

, Germany, on March 30, 1995. The program consisted of two Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( ; ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

sonatas and Reger's ''Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Beethoven'', a piece for two pianos, which Richter performed with pianist Andreas Lucewicz.

At the time of his death, he was rehearsing Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; ; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a List of compositions ...

's '' Fünf Klavierstücke'', D. 459.

Repertoire

As Richter once put it, "My repertory runs to around eighty different programs, not counting chamber works." His repertoire ranged fromHandel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( ; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti.

Born in Halle, Germany, H ...

and Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: �joːhan zeˈbasti̯an baχ ( – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety of instruments and forms, including the or ...

to Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer during the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally. Tchaikovsky wrote some of the most popular ...

, Scriabin, Szymanowski, Berg, Webern

Anton Webern (; 3 December 1883 – 15 September 1945) was an Austrian composer, conductor, and musicologist. His music was among the most radical of its milieu in its lyric poetry, lyrical, poetic concision and use of then novel atonality, aton ...

, Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ( – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and American citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of ...

, Bartók, Hindemith, Britten, and Gershwin.

Richter worked tirelessly to learn new pieces. For instance, in the late 1980s, he learned Brahms's Paganini and Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel ( ; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well-known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concerti.

Born in Halle, Germany, H ...

Variations, and in the 1990s, several of Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

's études and pieces by Gershwin, and works by Bach and Mozart that he had not previously included in his programs.

Central to his repertoire were the works of Schubert, Schumann

Robert Schumann (; ; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic music, Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber ...

, Beethoven, J. S. Bach, Chopin, Liszt, Prokofiev and Debussy.Monsaingeon, pp. 383–406. He is said to have learned and memorized the second book of Bach's ''The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time ''clavier'' referred to a variety of keyboard instruments, ...

'' in one month.

He gave the premiere of Prokofiev's Sonata No. 7, which he learned in four days, and No. 9, which Prokofiev dedicated to Richter. Apart from his solo career, he also performed chamber music

Chamber music is a form of classical music that is composed for a small group of Musical instrument, instruments—traditionally a group that could fit in a Great chamber, palace chamber or a large room. Most broadly, it includes any art music ...

with partners such as Mstislav Rostropovich

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich (27 March 192727 April 2007) was a Russian Cello, cellist and conducting, conductor. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was well known for both inspiring and commissioning new works, which enl ...

, Rudolf Barshai, David Oistrakh

David Fyodorovich Oistrakh (; – 24 October 1974) was a Soviet Russian violinist, List of violists, violist, and Conducting, conductor. He was also Professor at the Moscow Conservatory, People's Artist of the USSR (1953), and Laureate of the ...

, Oleg Kagan, Yuri Bashmet

Yuri Abramovich Bashmet (born 24 January 1953) is a Russian conductor, violinist, and violist.

Biography

Yuri Bashmet was born on 24 January 1953 in Rostov-on-Don in the family of Abram Borisovich Bashmet and Maya Zinovyeva Bashmet (née Kri ...

, Natalia Gutman

Natalia Grigoryevna Gutman (; born 14 November 1942), PAU, is a Russian cellist. She began to study cello at the Moscow Music School with R. Sapozhnikov. She was later admitted to the Moscow Conservatory. She later studied with Mstislav Rostrop ...

, Zoltán Kocsis

Zoltán Kocsis (; 30 May 1952 – 6 November 2016) was a Hungarian pianist, conducting, conductor and composer.

Biography

Studies

Born in Budapest, he began his musical studies at the age of five and continued them at the Béla Bartók Conser ...

, Elisabeth Leonskaja, Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten of Aldeburgh (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, o ...

and members of the Borodin Quartet. Richter also often accompanied singers such as Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (; 28 May 1925 – 18 May 2012) was a German lyric baritone and conductor of classical music. One of the most famous Lieder (art song) performers of the post-war period, he is best known as a singer of Franz Schubert's ...

, Peter Schreier, Galina Pisarenko and his wife and long-time artistic companion Nina Dorliak.

Richter also conducted the premiere of Prokofiev's Symphony-Concerto for cello and orchestra. This was his sole appearance as a conductor. The soloist was Rostropovich, to whom the work was dedicated. Prokofiev also wrote his 1949 Cello Sonata in C for Rostropovich, and he and Richter premiered it in 1950. Richter himself was a passable cellist, and Rostropovich was a good pianist; at one concert in Moscow at which he accompanied Rostropovich on the piano, they exchanged instruments for part of the program.

Approach to performance

Richter explained his approach to performance as follows: "The interpreter is really an executant, carrying out the composer's intentions to the letter. He doesn't add anything that isn't already in the work. If he is talented, he allows us to glimpse the truth of the work that is in itself a thing of genius and that is reflected in him. He shouldn't dominate the music, but should dissolve into it."Monsaingeon, p. 153. "I am not a complete idiot, but whether from weakness or laziness have no talent for thinking. I know only how to reflect: I am a mirror ... Logic does not exist for me. I float on the waves of art and life and never really know how to distinguish what belongs to the one or the other or what is common to both. Life unfolds for me like a theatre presenting a sequence of somewhat unreal sentiments; while the things of art are real to me and go straight to my heart." Richter's belief that musicians should "carry ... out the composer's intentions to the letter", led him to be critical of others and, most often, himself. After attending a recital ofMurray Perahia

Murray David Perahia ( ; born April 19, 1947) is an American pianist and conductor. He has been considered one of the greatest living pianists. He was the first North American pianist to win the Leeds International Piano Competition, in 1972. ...

, where Perahia performed Chopin's Third Piano Sonata without observing the first movement repeat, Richter asked him backstage to explain the omission. Similarly, after Richter realised that he had been playing a wrong note in Bach's Italian Concerto for decades, he insisted that the following disclaimer/apology be printed on a CD containing a performance thereof: "Just now Sviatoslav Richter realised, much to his regret, that he always made a mistake in the third measure before the end of the second part of the 'Italian Concerto'. As a matter of fact, through forty years – and no musician or technician ever pointed it out to him – he played 'F-sharp' rather than 'F'. The same mistake can be found in the previous recording made by Maestro Richter in the fifties."

Recordings

Despite his large discography, Richter disliked making studio recordings, and most of his recordings originate from live performances. Thus, his live recitals from Moscow (1948),Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

(1954 and 1972), Sofia

Sofia is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain, in the western part of the country. The city is built west of the Is ...

(1958), New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

(1960), Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

(1963), Aldeburgh

Aldeburgh ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish in the East Suffolk District, East Suffolk district, in the English county, county of Suffolk, England, north of the River Alde. Its estimated population was 2,276 in 2019. It was home to the comp ...

(multiple years), la Grange de Meslay near Tours

Tours ( ; ) is the largest city in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabita ...

(multiple years), Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

(multiple years), Salzburg

Salzburg is the List of cities and towns in Austria, fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020 its population was 156,852. The city lies on the Salzach, Salzach River, near the border with Germany and at the foot of the Austrian Alps, Alps moun ...

(1977) and Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

(1986), are considered among the finest documents of his playing, as are other live recordings issued during his lifetime and since his death on labels including Music & Arts, BBC Legends, Philips, Russia Revelation, Parnassus, and Ankh Productions.

Other critically acclaimed live recordings by Richter include performances of Scriabin's selected études, preludes and sonatas (multiple performances), Schumann

Robert Schumann (; ; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic music, Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber ...

's C major Fantasy (multiple performances), Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

's Piano Sonata No. 23 (Moscow, 1960), Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; ; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. Despite his short life, Schubert left behind a List of compositions ...

's B-flat Sonata (multiple performances), Mussorgsky's '' Pictures at an Exhibition'' (Sofia, 1958), Ravel's ''Miroirs'' (Prague, 1965), Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic period. With a diverse body of work spanning more than six decades, he is considered to be one of the most pro ...

's B minor Sonata (multiple performances, 1965–66), Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 29 (multiple performances, 1975) and selected preludes by Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of ...

(multiple performances) and Debussy

Achille Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionism in music, Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influe ...

(multiple performances).

Despite his professed aversion for the studio, Richter took the recording process seriously. For instance, after a long recording session for Schubert's ''Wanderer Fantasy

The Fantasie in C major, Op. 15 ( D. 760), popularly known as the ''Wanderer Fantasy'', is a four-movement fantasy for solo piano composed by Franz Schubert in 1822. It is widely considered Schubert's most technically demanding composition for th ...

'', for which he had used a Bösendorfer

Bösendorfer (L. Bösendorfer Klavierfabrik GmbH) is an Austrian piano manufacturer and, since 2008, a wholly owned subsidiary of Yamaha Corporation. Bösendorfer is unusual in that it produces Imperial Bösendorfer, 97- and 92-Key (instrument) ...

piano, Richter listened to the tapes and, dissatisfied with his performance, told the recording engineer "Well, I think we'll remake it on the Steinway after all". Similarly, during a recording session for Schumann

Robert Schumann (; ; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and music critic of the early Romantic music, Romantic era. He composed in all the main musical genres of the time, writing for solo piano, voice and piano, chamber ...

's Toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virt ...

, Richter reportedly chose to play this piece (which Schumann himself considered "among the most difficult pieces ever written") several times in a row, without taking any breaks, in order to preserve the spontaneity of his interpretation.

According to Falk Schwartz and John Berrie's 1983 article "Sviatoslav Richter – A Discography", in the 1970s, Richter announced his intention of recording his complete solo repertoire "on some 50 discs". This "complete" Richter project did not come to fruition, however, although twelve LPs worth of recordings were made between 1970 and 1973 and were subsequently reissued (in CD format) by Olympia (various composers, 10 CDs) and RCA Victor

RCA Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Group Corporation. It is one of Sony Music's four flagship labels, alongside Columbia Records (its former longtime rival), Arista Records and Epic ...

(Bach's ''The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time ''clavier'' referred to a variety of keyboard instruments, ...

'').

In 1961

Events January

* January 1 – Monetary reform in the Soviet Union, 1961, Monetary reform in the Soviet Union.

* January 3

** United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower announces that the United States has severed diplomatic and cons ...

, Richter's RCA Victor recording with Erich Leinsdorf and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) is an American symphony orchestra based in Chicago, Illinois. Founded by Theodore Thomas in 1891, the ensemble has been based in the Symphony Center since 1904 and plays a summer season at the Ravinia F ...

of the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 won the Grammy Award

The Grammy Awards, stylized as GRAMMY, and often referred to as The Grammys, are awards presented by The Recording Academy of the United States to recognize outstanding achievements in music. They are regarded by many as the most prestigious ...

for Best Classical Performance – Concerto or Instrumental Soloist. That recording is still considered a landmark (despite Richter's dissatisfaction with it), as are his studio recordings of Schubert's ''Wanderer Fantasy'', Liszt's two Piano Concertos, Rachmaninoff's Second Piano Concerto and Schumann's Toccata, among many others.

In film

Richter appeared in a 1952 Soviet film, playingLiszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic period. With a diverse body of work spanning more than six decades, he is considered to be one of the most pro ...

in '' Kompozitor Glinka'' (''The Composer Glinka''; Russian: ''Композитор Глинка'').

Bruno Monsaingeon interviewed Richter in 1995 (two years before his death) and the documentary The Enigma was released in 1998.

Reception

Memorable statements about Richter

The Italian critic Piero Rattalino has asserted that the only pianists comparable to Richter in the history of piano performance were

The Italian critic Piero Rattalino has asserted that the only pianists comparable to Richter in the history of piano performance were Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, virtuoso pianist, conductor and teacher of the Romantic music, Romantic period. With a diverse List of compositions by Franz Liszt, body of work spanning more than six ...

and Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni (1 April 1866 – 27 July 1924) was an Italian composer, pianist, conductor, editor, writer, and teacher. His international career and reputation led him to work closely with many of the leading musicians, artists and literary ...

.

Glenn Gould called Richter "one of the most powerful communicators the world of music has produced in our time".Bruno Monsaingeon, The Enigma (film biography of Richter).

Nathan Milstein described Richter in his memoir ''From Russia to the West'' as the following: "Richter was certainly a marvellous pianist but not as impeccable as he was reputed to be. His music making was too dry for me. In Richter's interpretation of Ravel's '' Jeux d'eau'', instead of flowing water you hear frozen icicles."

Van Cliburn

Harvey Lavan "Van" Cliburn Jr. (July 12, 1934February 27, 2013) was an American pianist. At the age of 23, Cliburn achieved worldwide recognition when he won the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958 during the Cold ...

attended a Richter recital in 1958 in the Soviet Union. He reportedly wept during the recital and, upon returning to the United States, described Richter's playing as "the most powerful piano playing I have ever heard".

Arthur Rubinstein

Arthur Rubinstein Order of the British Empire, KBE OMRI (; 28 January 1887 – 20 December 1982) was a Polish Americans, Polish-American pianist.

described his first exposure to Richter as follows: "It really wasn't anything out of the ordinary. Then at some point I noticed my eyes growing moist: tears began rolling down my cheeks."

Heinrich Neuhaus described Richter as follows: "His singular ability to grasp the whole and at the same time miss none of the smallest details of a composition suggests a comparison with an eagle who from his great height can see as far as the horizon and yet single out the tiniest detail of the landscape."

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Shostak ...

wrote of Richter: "Richter is an extraordinary phenomenon. The enormity of his talent staggers and enraptures. All the phenomena of musical art are accessible to him."

Vladimir Sofronitsky proclaimed that Richter was a "genius", prompting Richter to respond that Sofronitsky was a "god".

Vladimir Horowitz

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz (November 5, 1989) was a Russian and American pianist. Considered one of the greatest pianists of all time, he was known for his virtuoso technique, timbre, and the public excitement engendered by his playing.

Life ...

said: "Of the Russian pianists, I like only one, Richter."

Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 19255 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war contemporary classical music.

Born in Montb ...

wrote of Richter: "His personality was greater than the possibilities offered to him by the piano, broader than the very concept of complete mastery of the instrument."The Music RoomRichter International Piano Competition

Marlene Dietrich

Marie Magdalene "Marlene" DietrichBorn as Maria Magdalena, not Marie Magdalene, according to Dietrich's biography by her daughter, Maria Riva ; however, Dietrich's biography by Charlotte Chandler cites "Marie Magdalene" as her birth name . (, ; ...

, who was Richter's friend, wrote in her autobiography, ''Marlene'': "One evening the audience sat around him on the stage. While he was playing a piece, a woman directly behind him collapsed and died on the spot. She was carried out of the hall. I was deeply impressed by this incident and thought to myself: "What an enviable fate, to die while Richter is playing! What a strong feeling for the music this woman must have had when she breathed out her life!" But Richter did not share this opinion, he was shaken".

'' Gramophone'' critic Bryce Morrison described Richter as follows: "Idiosyncratic, plain-speaking, heroic, reserved, lyrical, virtuosic and perhaps above all, profoundly enigmatic, Sviatoslav Richter remains one of the greatest recreative artists of all time."

Memorable statements by Richter

On listening toBach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: �joːhan zeˈbasti̯an baχ ( – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety of instruments and forms, including the or ...

: "It does no harm to listen to Bach from time to time, even if only from a hygienic standpoint."

On Scriabin: "Scriabin isn't the sort of composer whom you'd regard as your daily bread, but is a heavy liqueur on which you can get drunk periodically, a poetical drug, a crystal that's easily broken."

On picking small venues for performance: "Put a small piano in a truck and drive out on country roads; take time to discover new scenery; stop in a pretty place where there is a good church; unload the piano and tell the residents; give a concert; offer flowers to the people who have been so kind as to attend; leave again."

On his plan to perform without a fee: "Music must be given to those who love it. I want to give free concerts; that's the answer."

On Neuhaus: "I learned a lot from him, even though he kept saying that there was nothing he could teach me. Music is written to be played and listened to and has always seemed to me to be able to manage without words... This was exactly the case with Heinrich Neuhaus. In his presence I was almost always reduced to total silence. This was an extremely good thing, as it meant that we concentrated exclusively on the music. Above all, he taught me the meaning of silence and the meaning of singing. He said I was incredibly obstinate and did only what I wanted to. It's true that I've only ever played what I wanted. And so he left me to do as I liked."

On playing: "I don't play for the audience, I play for myself, and if I derive any satisfaction from it, then the audience, too, is content."

After playing some Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( ; ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions ...

for a television programme whilst touring in the US, Richter said, after much coaxing by the interviewer and embarrassment on his own part, that Haydn was "better than Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756 – 5 December 1791) was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition and proficiency from an early age ...

".

Honours and awards

* Stalin Prize (1950); * People's Artist of the RSFSR (1955); *Grammy Award

The Grammy Awards, stylized as GRAMMY, and often referred to as The Grammys, are awards presented by The Recording Academy of the United States to recognize outstanding achievements in music. They are regarded by many as the most prestigious ...

(1960);

* Lenin Prize

The Lenin Prize (, ) was one of the most prestigious awards of the Soviet Union for accomplishments relating to science, literature, arts, architecture, and technology. It was originally created on June 23, 1925, and awarded until 1934. During ...

(1961);

* People's Artist of the USSR

People's Artist of the USSR, also sometimes translated as National Artist of the USSR, was an honorary title granted to artists of the Soviet Union. The term is confusingly used to translate two Russian language titles: Народный арти ...

(1961);

* Robert Schumann Prize of the City of Zwickau (1968);

* Honorary Doctor of the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

(1977);

* Léonie Sonning Music Prize (1986; Denmark);

* Hero of Socialist Labour

The Hero of Socialist Labour () was an Title of honor, honorific title in the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries from 1938 to 1991. It represented the highest degree of distinction in the USSR and was awarded for exceptional achievem ...

(1975);

* Three Orders of Lenin (1965, 1975, 1985);

* Order of the October Revolution

The Order of the October Revolution (, ''Orden Oktyabr'skoy Revolyutsii'') was instituted on 31 October 1967, in time for the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. It was conferred upon individuals or groups for services furthering communis ...

(1980);

* Glinka State Prize of the RSFSR (1987) – for concert programmes in 1986, performed in the cities of Siberia and the Far East;

* Order of Merit for the Fatherland

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* ...

, 4th class (1995);

* Russian Federation State Prize (1996);

* Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (France);

* Doctor of Music, ''honoris causa'' Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

;

* Voted into the Gramophone Hall of Fame in 2012;

* A minor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

, 9014 Svyatorichter, was named after him.

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * Monsaingeon, Bruno (1998), ''Richter, the Enigma''. Video interview-documentary. * * * *External links

*Website dedicated to Sviatoslav Richter, includes an extensive discography

* ttp://www.neuhaus.it/english/dorliak.html Brief obituary of Nina Dorliak

Paul Geffen, 1999:

''Vita'' of Sviatoslav Richter

Pete Taylor, 2010:

Concert list program with Google Earth maps

Sviatoslav Richter's memorial website (in Russian)

Website of Memorial Richter's apartment

{{DEFAULTSORT:Richter, Sviatoslav 1915 births 1997 deaths Soviet composers Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery Classical piano duos Deutsche Grammophon artists Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Commandeurs of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres Glinka State Prize of the RSFSR winners Grammy Award winners Heroes of Socialist Labour Recipients of the Lenin Prize Moscow Conservatory alumni People's Artists of the USSR People's Artists of the RSFSR Musicians from Odesa Recipients of the Léonie Sonning Music Prize Recipients of the Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 3rd class Recipients of the Order of Lenin Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Russian classical pianists Male classical pianists Russian people of German descent Soviet classical pianists State Prize of the Russian Federation laureates Recipients of the Stalin Prize Ukrainian people of German descent Ukrainian people of Russian descent Music & Arts artists 20th-century Russian male musicians