Surcouf (N N 3) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

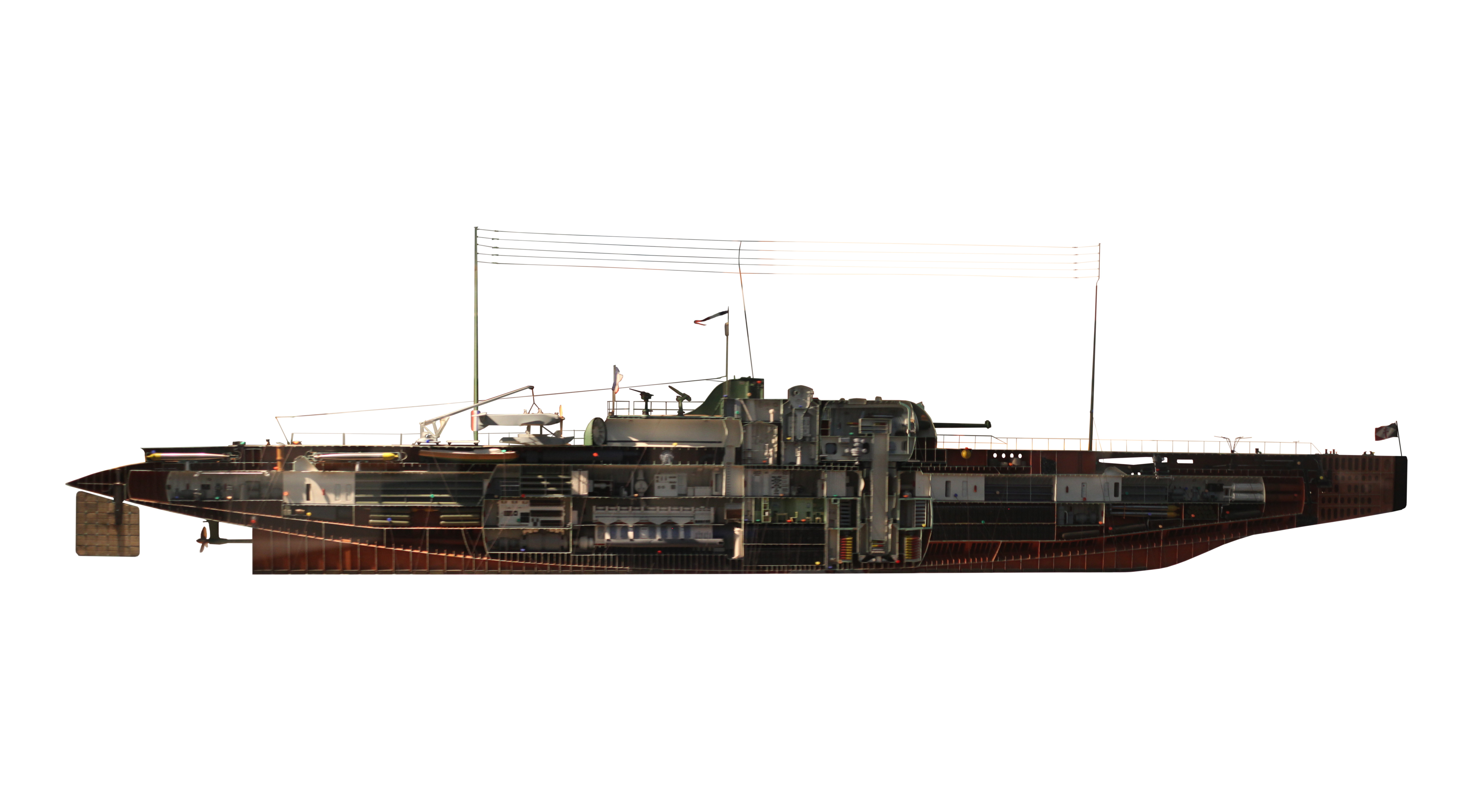

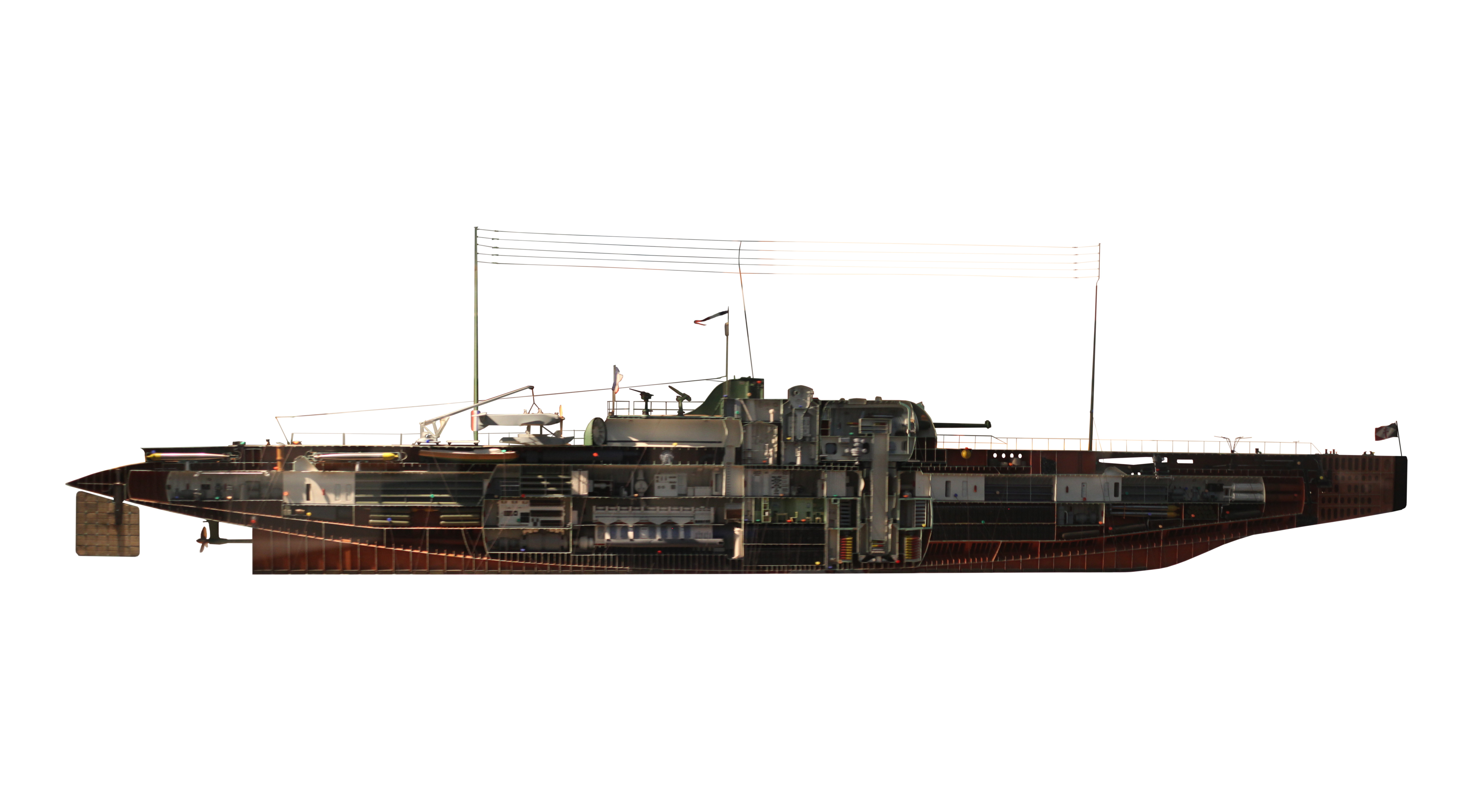

''Surcouf'' was a large French gun-armed

/ref> The Besson observation plane could be used to direct fire out to the guns' maximum range. Anti-aircraft cannon and machine guns were mounted on the top of the hangar. ''Surcouf'' also carried a motorboat, and contained a cargo compartment with fittings to restrain 40 prisoners or lodge 40 passengers. The submarine's fuel tanks were very large; having enough fuel for a range and supplies for 90-day patrols. The test depth was . The first commanding officer was

netmarine but other 'big-gun' submarines of this boat's class could no longer be built.

As there is no conclusive confirmation that ''Thompson Lykes'' collided with ''Surcouf'', and her wreck has yet to be discovered, there are alternative stories of her fate.

As there is no conclusive confirmation that ''Thompson Lykes'' collided with ''Surcouf'', and her wreck has yet to be discovered, there are alternative stories of her fate.

NN3 Specs

Roll of Honor {{DEFAULTSORT:Surcouf, French submarine Submarines of the French Navy Submarine aircraft carriers Ships built in France 1929 ships World War II submarines of France Submarines of the Free French Naval Forces Submarines sunk in collisions World War II shipwrecks in the Caribbean Sea International maritime incidents Maritime incidents in the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in July 1940 Maritime incidents in February 1942 Warships lost with all hands Submarines lost with all hands Surface-underwater ships Lost submarines of France

cruiser submarine

A cruiser submarine was a very large submarine designed to remain at sea for extended periods in areas distant from base facilities. Their role was analogous to surface cruisers; 'cruising' distant waters, commerce raiding, and otherwise operatin ...

of the mid 20th century. She carried two 203 mm guns as well as anti-aircraft guns and (for most of her career) a floatplane. ''Surcouf'' served in the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

and, later, the Free French Naval Forces

The Free French Naval Forces (, or FNFL) were the naval arm of the Free French Forces during the Second World War. They were commanded by Admiral Émile Muselier.

History

In the wake of the Armistice and the Appeal of 18 June, Charles de Ga ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

''Surcouf'' disappeared during the night of 18/19 February 1942 in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

, possibly after colliding with the US freighter ''Thompson Lykes'', although this has not been definitely established. She was named after the French privateer and shipowner Robert Surcouf

Robert Surcouf (; 12 December 1773 – 8 July 1827) was a French privateer, businessman and slave trader who operated in the Indian Ocean from 1789 to 1808 during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Capturing over 40 prizes, he ...

. She was the largest submarine built until surpassed by the first Japanese I-400 class aircraft carrier submarine in 1944.

Design

TheWashington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

had placed strict limits on naval construction by the major naval powers in regard to displacements and artillery calibers of battleships and cruisers. However, no agreements were reached in respect of light ships such as frigates, destroyers or submarines. In addition, to ensure the country's protection and that of the empire, France started the construction of an important submarine fleet (79 units in 1939). ''Surcouf'' was intended to be the first of a class of three submarine cruisers; however, she was the only one completed.

The missions revolved around:

* Ensuring contact with the French colonies

From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire existed mainly in the Americas and Asia. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the second French colonial empire existed mainly in Africa and Asia. France had about 80 colonie ...

;

* In collaboration with French naval squadrons, searching for and destroying enemy fleets;

* Pursuing enemy convoys.

''Surcouf'' had a twin-gun turret with 203 mm (8-inch) guns, the same calibre as the guns of a heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

, provisioned with 60 rounds. She was designed as an "underwater heavy cruiser", intended to seek out and engage in surface combat. The boat carried a Besson MB.411 observation floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

in a hangar built aft of the conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

for reconnaissance and observing fall of shot.

The boat was equipped with ten torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s: four tubes in the bow, and two swiveling external launchers in the aft superstructure, each with one 550 mm and two torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

tubes. Eight 550 mm and four 400 mm reloads were carried. The 203 Modèle 1924 guns were in a pressure-tight turret forward of the conning tower. The guns had a 60-round magazine capacity and were controlled by a director

Director may refer to:

Literature

* ''Director'' (magazine), a British magazine

* ''The Director'' (novel), a 1971 novel by Henry Denker

* ''The Director'' (play), a 2000 play by Nancy Hasty

Music

* Director (band), an Irish rock band

* ''D ...

with a rangefinder, mounted high enough to view an horizon, and able to fire within three minutes after surfacing. Using the boat's periscopes to direct the fire of the main guns, ''Surcouf'' could increase the visible range to ; originally an elevating platform was supposed to lift lookouts high, but this design was abandoned quickly due to the effect of roll

Roll may refer to:

Physics and engineering

* Rolling, a motion of two objects with respect to each-other such that the two stay in contact without sliding

* Roll angle (or roll rotation), one of the 3 angular degrees of freedom of any stiff bo ...

.Sous-marin croiseur ''Surcouf'': Caractéristiques principales/ref> The Besson observation plane could be used to direct fire out to the guns' maximum range. Anti-aircraft cannon and machine guns were mounted on the top of the hangar. ''Surcouf'' also carried a motorboat, and contained a cargo compartment with fittings to restrain 40 prisoners or lodge 40 passengers. The submarine's fuel tanks were very large; having enough fuel for a range and supplies for 90-day patrols. The test depth was . The first commanding officer was

Frigate Captain

Frigate captain is a naval rank in the naval forces of several countries. Corvette captain lies one level below frigate captain.

It is usually equivalent to the Commonwealth/US Navy rank of commander.

Countries using this rank include Argenti ...

(''Capitaine de Frégate'', a rank equivalent to Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

) Raymond de Belot.

The boat encountered several technical challenges:

* Because of the low height of the rangefinder above the water surface, the practical range of fire was with the rangefinder, increased to with sighting aided by periscope, well below the guns' maximum range of .

* The duration between the surface order and the first firing round was 3 minutes and 35 seconds. This duration would be longer if the boat was to fire broadside, which meant surfacing and training

Training is teaching, or developing in oneself or others, any skills and knowledge or fitness that relate to specific useful competencies. Training has specific goals of improving one's capability, capacity, productivity and performance. I ...

the turret in the desired direction.

* Firing had to occur at a precise moment of pitch and roll when the ship was level.

* Training the turret to either side was impossible when the ship rolled 8° or more.

* ''Surcouf'' could not fire accurately at night, as fall of shot could not be observed in the dark.

* The guns' ready magazines

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

had to be reloaded after firing 14 rounds from each gun.

To replace the floatplane, whose functioning was initially constrained and limited in use, trials were conducted with an autogyro

An autogyro (from Greek and , "self-turning"), gyroscope, gyrocopter or gyroplane, is a class of rotorcraft that uses an unpowered rotor in free autorotation to develop lift. A gyroplane "means a rotorcraft whose rotors are not engine-d ...

in 1938.

Appearance

'From the beginning of the boat's career until 1932, the boat was painted the same grey colour as surface warships, but thereafter in '' Prussian dark blue'', a colour which was retained until the end of 1940 when it was repainted with two tones of grey, serving as camouflage on the hull and conning tower.Career

Early career

Soon after ''Surcouf'' was launched, theLondon Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Empire of Japan, Japan, French Third Republic, France, Kingdom of Italy, Italy, and the United Stat ...

finally placed restrictions on submarine designs. Among other things, each signatory (France included) was permitted to possess no more than three large submarines, each not exceeding standard displacement, with guns not exceeding in caliber. ''Surcouf'', which would have exceeded these limits, was specially exempt from the rules at the insistence of Navy Minister Georges Leygues

Georges Leygues (; 29 October 1856 – 2 September 1933) was a French politician of the Third Republic. During his time as Minister of Marine he worked with the navy's chief of staff Henri Salaun in unsuccessful attempts to gain naval re-arm ...

,Croiseur sous-marin ''Surcouf''netmarine but other 'big-gun' submarines of this boat's class could no longer be built.

Second World War

In 1940, ''Surcouf'' was based inCherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

, but in May, when the Germans invaded, she was being refitted in Brest following a mission in the Antilles

The Antilles is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mexico to the northwest, and the Atlantic Ocean to the north and east.

The Antillean islands are divided into two smaller groupings: the Greater An ...

and Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea (French language, French: ''Golfe de Guinée''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Golfo de Guinea''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Golfo da Guiné'') is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez i ...

. Under command of Frigate Captain Martin, unable to dive and with only one engine functioning and a jammed rudder, she limped across the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

and sought refuge in Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

.

On 3 July, the British, concerned that the French Fleet would be taken over by the German ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

'' at the French armistice, executed Operation Catapult

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

. The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

blockaded the harbours where French warships were anchored, and delivered an ultimatum: rejoin the fight against Germany, be put out of reach of the Germans, or scuttle. Few accepted willingly; the North African fleet at Mers-el-Kebir and the ships based at Dakar (French West Africa) refused. The French battleships in North Africa were eventually attacked and all but one sunk at their moorings by the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

.

French ships lying at ports in Britain and Canada were also boarded by armed marines, sailors and soldiers, but the only serious incident took place at Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

aboard ''Surcouf'' on 3 July, when two Royal Navy submarine officers, Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

Denis 'Lofty' Sprague, captain of , and Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

Patrick Griffiths of , and French warrant officer mechanic Yves Daniel were fatally wounded, and a British seaman, Albert Webb, was shot dead by the submarine's doctor.

Free French Naval Forces

By August 1940, the British completed ''Surcouf''s refit and turned her over to theFree French Naval Forces

The Free French Naval Forces (, or FNFL) were the naval arm of the Free French Forces during the Second World War. They were commanded by Admiral Émile Muselier.

History

In the wake of the Armistice and the Appeal of 18 June, Charles de Ga ...

(''Forces Navales Françaises Libres'', FNFL) for convoy patrol. The only officer not repatriated from the original crew, Frigate Captain Georges Louis Blaison, became the new commanding officer. Because of Anglo-French tensions with regard to the submarine, accusations were made by each side that the other was spying for Vichy France

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the Battle of France, ...

; the British also claimed ''Surcouf'' was attacking British ships. Later, a British officer and two sailors were put aboard for "liaison" purposes. One real drawback was she required a crew of 110–130 men, which represented three crews of more conventional submarines. This led to Royal Navy reluctance to recommission her.

''Surcouf'' then went to the Canadian base at Halifax, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

and escorted trans-Atlantic convoys. In April 1941, she was damaged by a German plane at Devonport.

On 28 July, ''Surcouf'' went to the United States Naval Shipyard at Kittery, Maine for a three-month refit.

After leaving the shipyard, ''Surcouf'' went to New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River in New London County, Connecticut, which empties into Long Island Sound. The cit ...

, perhaps to receive additional training for her crew. ''Surcouf'' left New London on 27 November to return to Halifax.

Capture of St. Pierre and Miquelon

In December 1941, ''Surcouf'' carried the Free French AdmiralÉmile Muselier

Émile Henry Muselier (; 17 April 1882 – 2 September 1965) was a French admiral who led the Free French Naval Forces ('' Forces navales françaises libres'', or FNFL) during World War II. He was responsible for the idea of distinguishing his ...

to Canada, putting into Quebec City

Quebec City is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Census Metropolitan Area (including surrounding communities) had a populati ...

. While the Admiral was in Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

, conferring with the Canadian government, ''Surcouf''s captain was approached by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' reporter Ira Wolfert and questioned about the rumours the submarine would liberate Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon ( ), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, located near the Canadian province of ...

for Free France. Wolfert accompanied the submarine to Halifax, where, on 20 December, they joined Free French "Escorteurs" corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the sloo ...

s ''Mimosa'', , and , and on 24 December, took control of the islands for Free France without resistance.

United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevel ...

had just concluded an agreement with the Vichy government guaranteeing the neutrality of French possessions in the Western hemisphere, and he threatened to resign unless President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

demanded a restoration of the status quo. Roosevelt did so, but when Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

refused, Roosevelt dropped the matter. Ira Wolfert's stories – very favourable to the Free French (and bearing no sign of kidnapping or other duress) – helped swing American popular opinion away from Vichy. The Axis Powers' declaration of war on the United States in December 1941 negated the agreement, but the U.S. did not sever diplomatic ties with the Vichy Government until November 1942.

Later operations

In January 1942, the Free French leadership decided to send ''Surcouf'' to the Pacific theatre, after she had been re-supplied at the Royal Naval Dockyard inBermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

. However, her movement south triggered rumours that ''Surcouf'' was going to liberate Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, Kariʼn ...

from the Vichy regime.

In fact, ''Surcouf'' was bound for Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

, Australia, via Tahiti. She departed Halifax on 2 February for Bermuda, which she left on 12 February, bound for the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

.

Fate

''Surcouf'' vanished on the night of 18/19 February 1942, about north of Cristóbal, Panama, while ''en route'' forTahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

, ''via'' the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

. An American report concluded the disappearance was due to an accidental collision with the American freighter . Steaming alone from Guantanamo Bay on what was a very dark night, the freighter reported hitting and running down a partially submerged object which scraped along her side and keel. Her lookouts heard people in the water but, thinking she had hit a U-boat, the freighter did not stop although cries for help were heard in English. A signal was sent to Panama describing the incident.

The loss resulted in 130 deaths (including 4 Royal Navy personnel), under the command of Frigate Captain Georges Louis Nicolas Blaison. The loss of ''Surcouf'' was announced by the Free French Headquarters in London on 18 April 1942, and was reported in ''The New York Times'' the next day. It was not reported ''Surcouf'' was sunk as the result of a collision with the ''Thompson Lykes'' until January 1945.

The investigation of the French commission concluded the disappearance was the consequence of misunderstanding. A Consolidated PBY

The Consolidated Model 28, more commonly known as the PBY Catalina (U.S. Navy designation), is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft designed by Consolidated Aircraft in the 1930s and 1940s. In U.S. Army service, it was designated as the OA ...

, patrolling the same waters on the night of 18/19 February, could have attacked ''Surcouf'' believing her to be German or Japanese.

Inquiries into the incident were haphazard and late, while a later French inquiry supported the idea that the sinking had been due to "friendly fire"; this conclusion was supported by Rear Admiral Gabriel Auphan

Counter-admiral Gabriel Paul Auphan (; November 4, 1894, Alès – April 6, 1982) was a French naval officer who became the State Secretary of the Navy (secrétaire d'État à la Marine) of the Vichy government from April to November 1942.

...

in his book ''The French Navy in World War II''. Charles de Gaulle stated in his memoirs that ''Surcouf'' "had sunk with all hands".

Legacy

As no one has officially dived or verified the wreck of ''Surcouf'', her location is unknown. If one assumes the ''Thompson Lykes'' incident was indeed the event of ''Surcouf's'' sinking, then the wreck would lie deep at . A monument commemorates the loss in the port ofCherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

in Normandy, France. The loss is also commemorated by the Free French Memorial on Lyle Hill

Lyle Hill stands at the West End of Greenock in Inverclyde, Scotland. It has scenic viewpoints accessible from Lyle Road, which was constructed in 1879–1880 and named after Provost Abram Lyle, well known as a sugar refiner. The hill's hi ...

in Greenock, Scotland.

As there is no conclusive confirmation that ''Thompson Lykes'' collided with ''Surcouf'', and her wreck has yet to be discovered, there are alternative stories of her fate.

As there is no conclusive confirmation that ''Thompson Lykes'' collided with ''Surcouf'', and her wreck has yet to be discovered, there are alternative stories of her fate. James Rusbridger

James Rusbridger (26 February 1928 – 16 February 1994) was a British author and historian on international espionage during and after World War II.

Biography

He was born in Jamaica, son of Gordon Rusbridger an Army colonel, and died in Tremo ...

examined some of these theories in his book ''Who Sank Surcouf?'', finding them all easily dismissible except one: the records of the 6th Heavy Bomber Group operating out of Panama show them sinking a large submarine the morning of 19 February. Since no German submarine was lost in the area on that date, she could have been ''Surcouf''. He suggested the collision had damaged ''Surcouf''s radio and the stricken boat limped towards Panama hoping for the best.

A conspiracy theory, based on no significant evidence, held that the ''Surcouf'', during her stationing at New London in late 1941, had been caught treacherously supplying a German U-boat in Long Island Sound, pursued by the American training subs ''Marlin

Marlins are fish from the family Istiophoridae, which includes between 9 and 11 species, depending on the taxonomic authority.

Name

The family's common name is thought to derive from their resemblance to a sailor's marlinspike.

Taxonomy

T ...

'' and ''Mackerel

Mackerel is a common name applied to a number of different species of pelagic fish, mostly from the family Scombridae. They are found in both temperate and tropical seas, mostly living along the coast or offshore in the oceanic environment.

...

'' out of New London, and sunk. The rumor circulated into the early 21st century, but is false since the ''Surcouf''s later movements south are well documented.

In popular media

The ''Surcouf'' is the subject of an underwater search by the fictional organization ''NUMA'' and international terrorists in theClive Cussler

Clive Eric Cussler (July 15, 1931 – February 24, 2020) was an American adventure novelist and underwater explorer. His thriller novels, many featuring the character Dirk Pitt, have been listed on ''The New York Times'' fiction best-sell ...

novel "The Corsican Shadow", published in 2023. Cussler and his co-writer, Dirk Cussler, writes the ''Surcouf''s wreck was discovered "...some eighty miles off the Panama coast." The sinking is even attributed to ''Surcouf''s radio antenna being damaged in the collision with the ''Thompson Lykes'', and then finished off by the reported attack of an A-17 bomber the next morning.

Douglas Reeman

Douglas Edward Reeman (15 October 1924 – 23 January 2017), who also used the pseudonym Alexander Kent, was a British author who wrote many historical novels about the Royal Navy, mainly set during either World War II or the Napoleonic Wars. He w ...

wrote "Strike from the Sea", a novel published in 1978, about a French cruiser submarine named "Soufriere", modeled on the Surcouf.

Honors

*''Médaille de la Résistance avec Rosette'' (Resistance Medal

The Resistance Medal (, ) was a decoration bestowed by the French Committee of National Liberation, based in the United Kingdom, during World War II. It was established by a decree of General Charles de Gaulle on 9 February 1943 "to recognize the ...

with rosette) - 29 November 1946

*Cited in Orders of Corps of the Army - 4 August 1945

*Cited in Orders of the Navy - 8 January 1947

See also

* French submarines of World War II *Fusiliers Marins

The ''Fusiliers marins'' (lit. "Sailor Riflemen") are specialized sailors of the ''Marine nationale'' (French Navy). The ''Fusiliers marins'' serve primarily as the Navy’s security forces, providing protection for naval vessels and naval inst ...

* Georges Cabanier

* HM Submarine ''X1''

*

*Japanese ''I-400''-class submarine

* USS Dorado (SS-248) a US submarine sunk in the same area under similar circumstances

*List of submarines of France

The submarines of France include Nuclear submarine, nuclear attack submarines and nuclear ballistic missile submarines of various List of submarine classes, classes, operated by the French Navy as part of the Submarine forces (France), French Subma ...

*Submarine aircraft carrier

A submarine aircraft carrier is a submarine equipped with aircraft for observation or attack missions. These submarines saw their most extensive use during World War II, although their operational significance remained rather small. The most fam ...

References

Bibliography

*External links

NN3 Specs

Roll of Honor {{DEFAULTSORT:Surcouf, French submarine Submarines of the French Navy Submarine aircraft carriers Ships built in France 1929 ships World War II submarines of France Submarines of the Free French Naval Forces Submarines sunk in collisions World War II shipwrecks in the Caribbean Sea International maritime incidents Maritime incidents in the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in July 1940 Maritime incidents in February 1942 Warships lost with all hands Submarines lost with all hands Surface-underwater ships Lost submarines of France