Sultanate of Zanzibar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sultanate of Zanzibar (, ), also known as the Zanzibar Sultanate, was an East African

File:Anglo-Zanzibar war map.png, Island of Unguja and the African mainland

File:Sultanat de Zanzibar vèrs 1875.png, Zanzibar's Sultanate

File:The Harem and Tower Harbour of Zanzibar (p.234, 1890) - Copy.jpg, The Harem and Tower Harbour of Zanzibar. 1890

File:Zanzibar 1964 Jamhuri overprint stamp.jpg, Independence stamp overprinted "Republic"

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

state controlled by the Sultan of Zanzibar, in place between 1856 and 1964. The Sultanate's territories varied over time, and after a period of decline, the state had sovereignty over only the Zanzibar Archipelago

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. The c ...

and a strip along the Kenyan coast, with the interior of Kenya constituting the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Kenya Colony

The Colony and Protectorate of Kenya, commonly known as British Kenya or British East Africa, was part of the British Empire in Africa from 1920 until 1963. It was established when the former East Africa Protectorate was transformed into a Brit ...

and the coastal strip administered as a ''de facto'' part of that colony.

Under an agreement reached on 8 October 1963, the Sultan of Zanzibar relinquished sovereignty over his remaining territory on the mainland, and on 12 December 1963, Kenya officially obtained independence from the British. On 12 January 1964, revolutionaries, led by the African Afro-Shirazi Party, overthrew the mainly Arab government. Jamshid bin Abdullah, the last sultan, was deposed and lost sovereignty over Zanzibar, marking the end of the Sultanate, and resulted in the massacre of tens of thousands of Arabs.

History

Founding

According to the 16th-century explorer Leo Africanus, Zanzibar (Zanguebar) was the term used by Arabs and Persians to refer to the eastern African coast running from Kenya to Mozambique, dominated by five semi-independent Muslim kingdoms:Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centr ...

, Kilwa, Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

, and Sofala. Africanus further noted that they all had standing agreements of loyalty with the major central African states, including the Kingdom of Mutapa.

In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the overseas holdings of Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

after Saif bin Sultan, the Imam of Oman, defeated the Portuguese in Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, in what is now Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

. In 1832 or 1840, Omani ruler Said bin Sultan moved his court from Muscat to Stone Town

Stonetown of Zanzibar (), also known as , is the old part of Zanzibar City, the main city of Zanzibar, in Tanzania. The newer portion of the city is known as Ng'ambo, Swahili for 'the other side'. Stone Town is located on the western coast of Un ...

on the island of Unguja (that is, Zanzibar Island). He established a ruling Arab elite and encouraged the development of clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands, or Moluccas, in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring, or Aroma compound, fragrance in fin ...

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

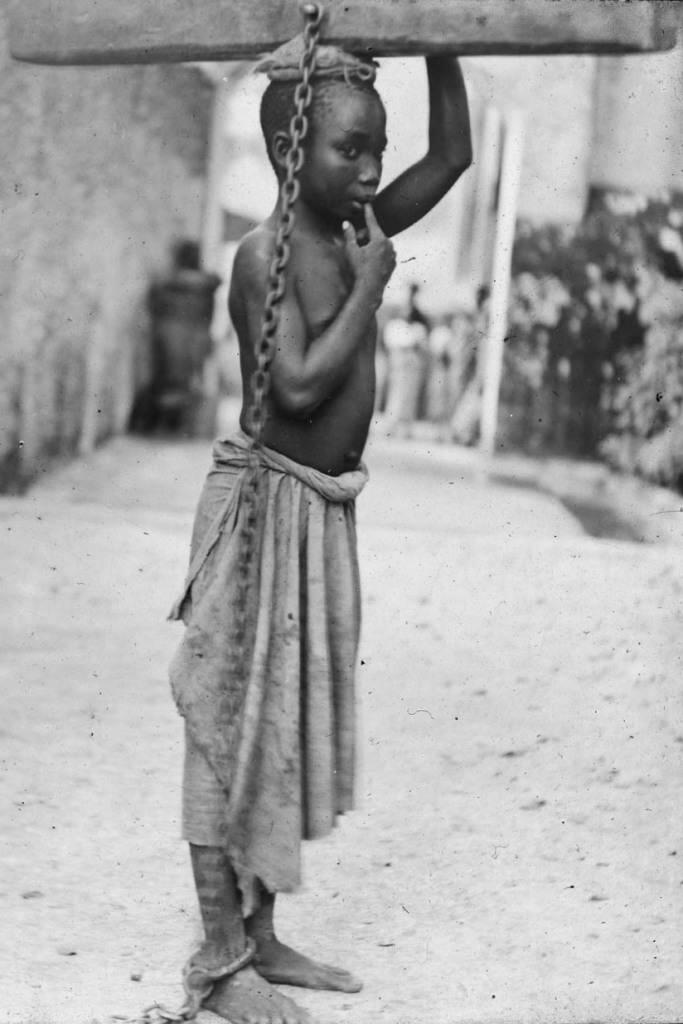

s, using the island's slave labour. The East African slave trade flourished greatly from the second half of the nineteenth century, when Said bin Sultan made Zanzibar his capital and expanded international commercial activities and plantation economy in cloves and coconuts.

Zanzibar's commerce fell increasingly into the hands of traders from the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

, whom Said encouraged to settle on the island. After his death in 1856, two of his sons, Majid bin Said and Thuwaini bin Said, struggled over the succession, so Zanzibar and Oman were divided into two separate realms. Thuwaini became the Sultan of Muscat and Oman while Majid became the first Sultan of Zanzibar, but obliged to pay an annual tribute to the Omani court in Muscat. During his 14-year reign as Sultan, Majid consolidated his power around the local slave trade. Pressed by the British, his successor, Barghash bin Said, helped abolish the slave trade in Zanzibar and largely developed the country's infrastructure. The third Sultan, Khalifa bin Said, also furthered the country's progress toward abolishing slavery.

Context for the Sultan's loss of control over his dominions

Until 1884, the Sultans of Zanzibar controlled a substantial portion of theSwahili Coast

The Swahili coast () is a coastal area of East Africa, bordered by the Indian Ocean and inhabited by the Swahili people. It includes Sofala (located in Mozambique); Mombasa, Gede, Kenya, Gede, Pate Island, Lamu, and Malindi (in Kenya); and Dar es ...

, known as Zanj, and trading routes extending further into the continent, as far as Kindu on the Congo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

. That year, however, the Society for German Colonization forced local chiefs on the mainland to agree to German protection, prompting Sultan Bargash bin Said to protest. Coinciding with the Berlin Conference and the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

, further German interest in the area was soon shown in 1885 by the arrival of the newly created German East Africa Company, which had a mission to colonize the area.

In 1886, the British and Germans secretly met and discussed their aims of expansion in the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

, with spheres of influence already agreed upon the year before, with the British to take what would become the East Africa Protectorate (now Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

) and the Germans to take present-day Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

. Both powers leased coastal territory from Zanzibar and established trading stations and outposts. Over the next few years, all of the mainland possessions of Zanzibar came to be administered by European imperial powers, beginning in 1888 when the Imperial British East Africa Company took over administration of Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

.

The same year the German East Africa Company acquired formal direct rule over the coastal area previously submitted to German protection. This resulted in a native uprising, the Abushiri revolt, which was suppressed by the '' Kaiserliche Marine'' and heralded the end of Zanzibar's influence on the mainland.

Establishment of the Zanzibar Protectorate

With the signing of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty between theUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

in 1890, Zanzibar itself became a British protectorate. In August 1896, following the death of Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, Britain and Zanzibar fought a 38-minute war, the shortest in recorded history. A struggle for succession took place as the Sultan's cousin Khalid bin Barghash seized power. The British instead wanted Hamoud bin Mohammed to become Sultan, believing that he would be much easier to work with. The British gave Khalid an hour to vacate the Sultan's palace in Stone Town. Khalid failed to do so, and instead assembled an army of 2,800 men to fight the British. The British launched an attack on the palace and other locations around the city after which Khalid retreated and later went into exile. Hamoud was then peacefully installed as Sultan.

That "Zanzibar" for these purposes included the coastal strip of Kenya that would later become the Protectorate of Kenya was a matter recorded in the parliamentary debates at the time.

Establishment of the East Africa Protectorate

In 1886, the British government encouraged William Mackinnon, who already had an agreement with the Sultan and whose shipping company traded extensively in theAfrican Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

, to increase British influence in the region. He formed a British East Africa Association which led to the Imperial British East Africa Company being chartered in 1888 and given the original grant to administer the territory. It administered about of coastline stretching from the River Jubba via Mombasa to German East Africa which were leased from the Sultan. The British "sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

", agreed at the Berlin Conference of 1885, extended up the coast and inland across the future Kenya and after 1890 included Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

as well. Mombasa was the administrative centre at this time.

However, the company began to fail, and on 1 July 1895 the British government proclaimed a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

, the East Africa Protectorate, the administration being transferred to the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

. In 1902, administration was again transferred to the Colonial Office and the Uganda territory was incorporated as part of the protectorate also. In 1897 Lord Delamere, the pioneer of white settlement, arrived in the Kenya highlands, which was then part of the Protectorate. Lord Delamere was impressed by the agricultural possibilities of the area. In 1902 the boundaries of the Protectorate were extended to include what was previously the Eastern Province of Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

. Also, in 1902, the East Africa Syndicate received a grant of to promote white settlement in the Highlands. Lord Delamere now commenced extensive farming operations, and in 1905, when a large number of immigrants arrived from Britain and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, the Protectorate was transferred from the authority of the Foreign Office to that of the Colonial Office. The capital was shifted from Mombasa to Nairobi

Nairobi is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Kenya. The city lies in the south-central part of Kenya, at an elevation of . The name is derived from the Maasai language, Maasai phrase , which translates to 'place of cool waters', a ...

in 1905. A regular Government and Legislature were constituted by Order in Council in 1906. This constituted the administrator a governor and provided for legislative and executive councils. Lieutenant Colonel J. Hayes Sadler was the first governor and commander in chief. There were occasional troubles with local tribes but the country was opened up by the colonial government with little bloodshed. After the First World War, more immigrants arrived from Britain and South Africa, and by 1919 the European population was estimated at 9,000 strong.

Loss of sovereignty over Kenya

On 23 July 1920, the inland areas of the East Africa Protectorate were annexed as British dominions by Order in Council. That part of the former Protectorate was thereby constituted as theColony of Kenya

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often o ...

and from that time, the Sultan of Zanzibar ceased to be sovereign over that territory. The remaining wide coastal strip (with the exception of Witu) remained a Protectorate under an agreement with the Sultan of Zanzibar. That coastal strip, remaining under the sovereignty of the Sultan of Zanzibar, was constituted as the Protectorate of Kenya in 1920.Kenya Protectorate Order in Council, 1920 S.R.O. 1920 No. 2343, S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. VIII, 258, State Pp., Vol. 87 p. 968

The Protectorate of Kenya was governed as part of the Colony of Kenya

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often o ...

by virtue of an agreement between the United Kingdom and the Sultan dated 14 December 1895.

The Colony of Kenya and the Protectorate of Kenya each came to an end on 12 December 1963. The United Kingdom ceded sovereignty over the Colony of Kenya and, under an agreement dated 8 October 1963, the Sultan agreed that simultaneously with independence for Kenya, the Sultan would cease to have sovereignty over the Protectorate of Kenya. In this way, Kenya became an independent country under the Kenya Independence Act 1963. Exactly 12 months later on 12 December 1964, Kenya became a republic under the name " Republic of Kenya".

End of the Zanzibar Protectorate and deposition of the Sultan

On 10 December 1963, the Protectorate that had existed over Zanzibar since 1890 was terminated by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom did not grant Zanzibar independence, as such, because the UK never had sovereignty over Zanzibar. Rather, by the Zanzibar Act 1963 of the United Kingdom, the UK ended the Protectorate and made provision for full self-government in Zanzibar as an independent country within the Commonwealth. Upon the Protectorate being abolished, Zanzibar became aconstitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

within the Commonwealth under the Sultan. Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah was overthrown a month later during the Zanzibar Revolution. Jamshid fled into exile, and the Sultanate was replaced by the People's Republic of Zanzibar. In April 1964, the existence of this socialist republic was ended with its union with Tanganyika to form the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, which became known as Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

six months later.

Demographics

By 1964, the country was aconstitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

within the Commonwealth ruled by Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah. Zanzibar had a population of around 230,000 natives, some of whom claimed Persian ancestry and were known locally as Shirazis. It also contained significant minorities in the 50,000 Arabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

and 20,000 South Asians who were prominent in business and trade. The various ethnic groups were becoming mixed and the distinctions between them had blurred; according to one historian, an important reason for the general support for Sultan Jamshid was his family's ethnic diversity. However, the island's Arab inhabitants, as the major landowners, were generally wealthier than the natives; the major political parties were organised largely along ethnic lines, with Arabs dominating the Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP) and natives the Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP).

See also

* List of sultans of ZanzibarReferences

Bibliography

* * * * * . * . * . *External links

* of the Zanzibar Royal Family * {{Authority control Former Commonwealth monarchiesZanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

Island countries of the Indian Ocean

1856 establishments in Africa

1964 disestablishments in Africa

Zanzibar, Sultanate of

Zanzibar, Sultanate of

States and territories established in 1856

States and territories disestablished in 1964

Tanzania and the Commonwealth of Nations

Former countries

Arab slave owners