Stowe Gardens, formerly Stowe Landscape Gardens, are extensive,

Grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

gardens and parkland in

Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshir ...

, England. Largely created in the 18th century, the gardens at Stowe are arguably the most significant example of the

English landscape garden

The English landscape garden, also called English landscape park or simply the English garden (, , , , ), is a style of "landscape" garden which emerged in England in the early 18th century, and spread across Europe, replacing the more formal ...

. Designed by

Charles Bridgeman

Charles Bridgeman (1690–1738) was an English garden designer who helped pioneer the naturalistic landscape style. Although he was a key figure in the transition of English garden design from the Anglo-Dutch formality of patterned parterres ...

,

William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, b ...

, and

Capability Brown

Lancelot "Capability" Brown (born c. 1715–16, baptised 30 August 1716 – 6 February 1783) was an English gardener and landscape architect, a notable figure in the history of the English landscape garden style.

Unlike other architects ...

, the gardens changed from a baroque park to a natural landscape garden, commissioned by the estate's owners, in particular by

Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham

Field Marshal Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham, (24 October 1675 – 14 September 1749) was a British army officer and Whig politician. After serving as a junior officer under William III during the Williamite War in Ireland and during th ...

, his nephew

Richard Grenville-Temple, 2nd Earl Temple

Richard Grenville-Temple, 2nd Earl Temple, KG, PC (26 September 1711 – 12 September 1779) was a British politician and peer who served as Lord Privy Seal from 1757 to 1761. He is best known for his association with his brother-in-law Willia ...

, and his nephew

George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham

George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham (17 June 1753 – 11 February 1813), known as George Grenville before 1779 and as The Earl Temple between 1779 and 1784, was a British statesman.

Background and early life

Grenville w ...

.

The gardens are notable for the scale, design, size and the number of monuments set across the landscape, as well as for the fact they have been a tourist attraction for over 300 years. Many of the monuments in the property have their own additional Grade I listing along with the park. These include: the Corinthian Arch, the Temple of Venus, the Palladian Bridge, the Gothic Temple, the Temple of Ancient Virtue, the Temple of British Worthies, the Temple of Concord and Victory, the Queen's Temple, Doric Arch, the Oxford Bridge, amongst others.

The gardens passed into the ownership of the

National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

in 1989, whilst

Stowe House

Stowe House is a grade I listed building, listed country house in Stowe, Buckinghamshire, Stowe, Buckinghamshire, England. It is the home of the Private schools in the United Kingdom, private Stowe School and is owned by the Stowe House Preserv ...

, the home of

Stowe School

The Stowe School is a public school (English private boarding school) for pupils aged 13–18 in the countryside of Stowe, England. It was opened on 11 May, 1923 at Stowe House, a Grade I Heritage Estate belonging to the British Crown. ...

, is under the care of the Stowe House Preservation Trust. The parkland surrounding the gardens is open 365 days a year.

History

The Stowe gardens and estate are located close to the village of

Stowe in

Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshir ...

, England.

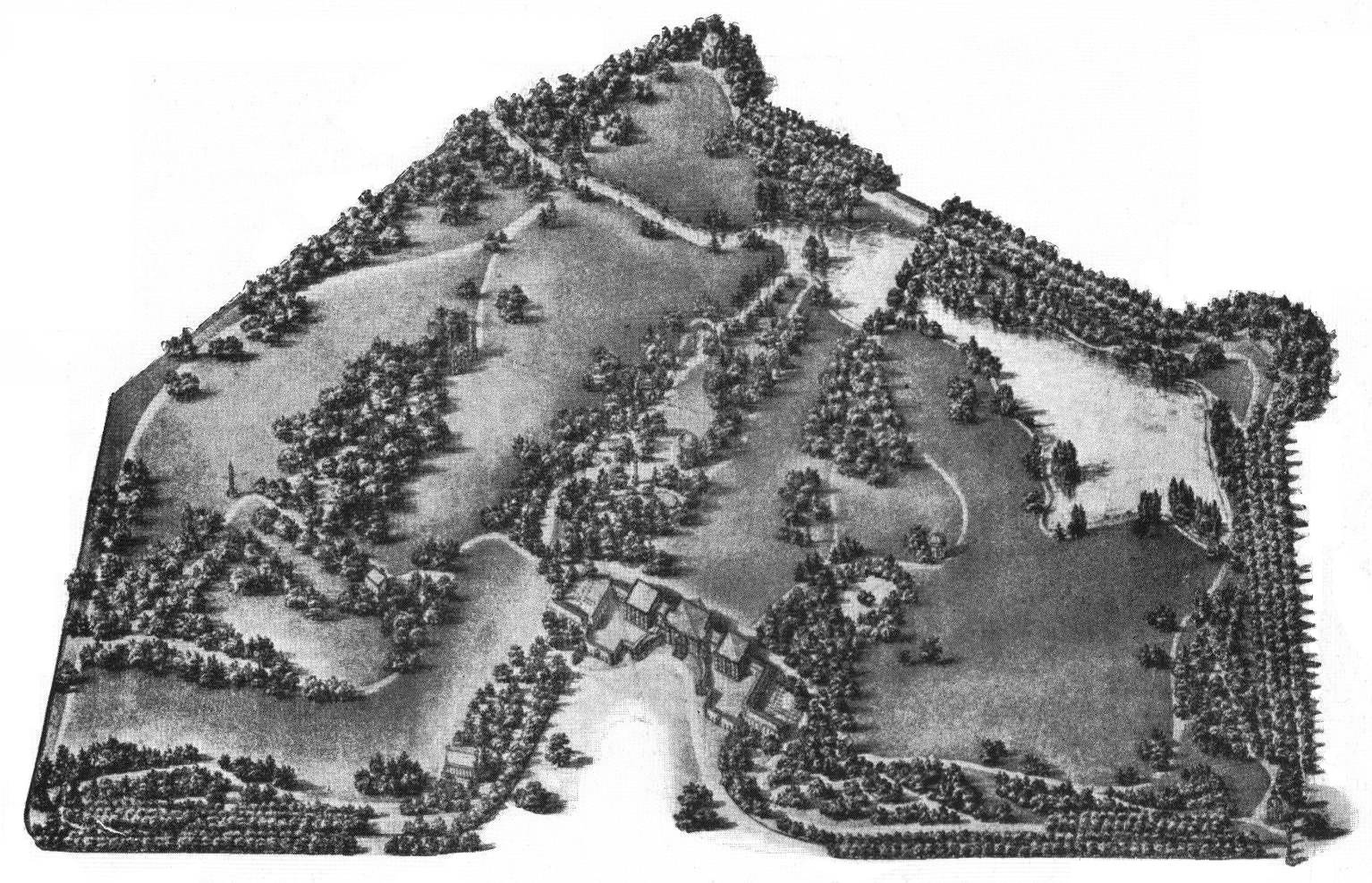

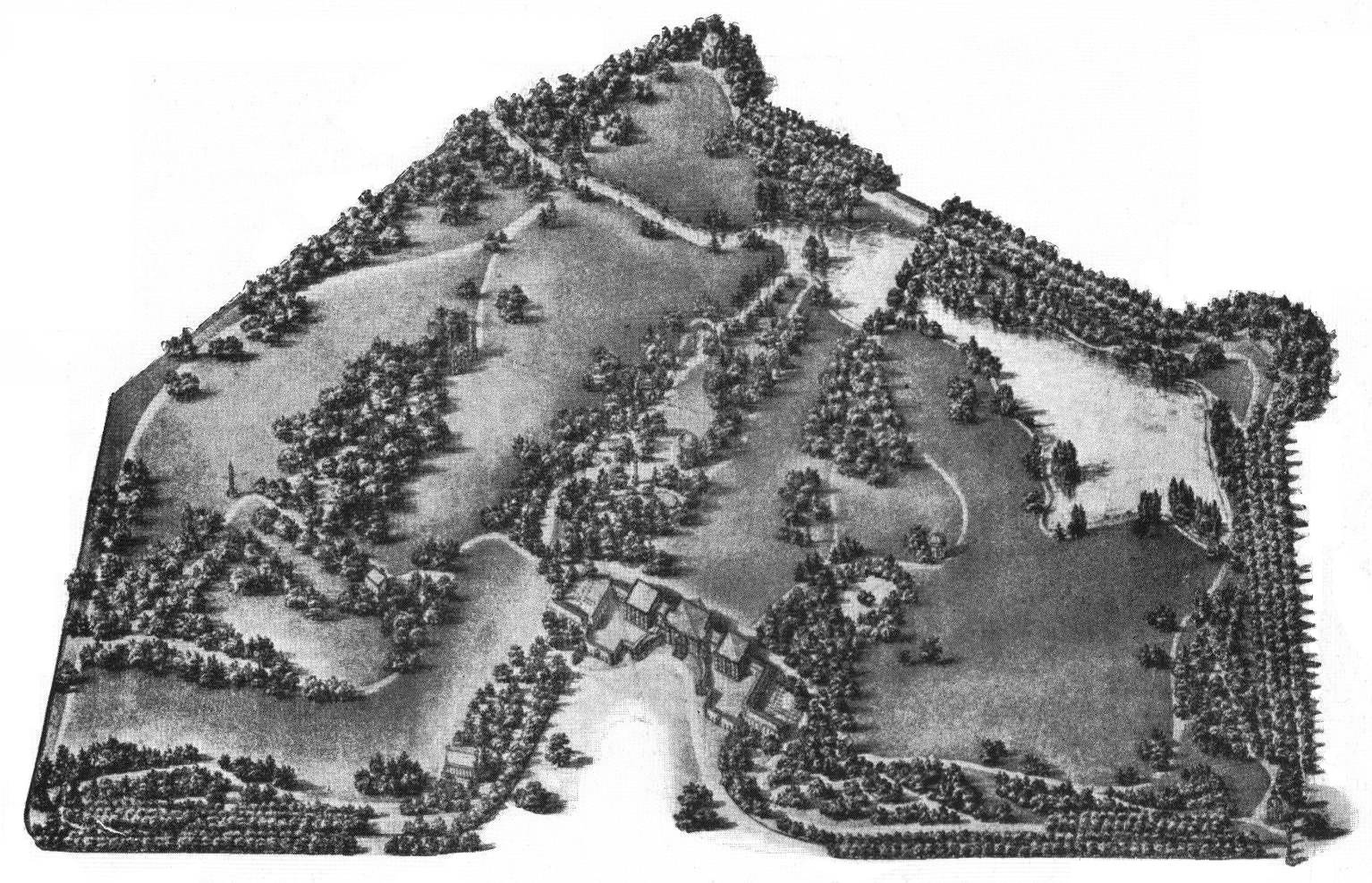

John Temple, a wealthy wool farmer, purchased the manor and estate in 1589. Subsequent generations of Temples inherited the estate, but it was with the succession of Sir Richard Temple that the gardens began to be developed, after the completion of a new house in 1683.

Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham

Field Marshal Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham, (24 October 1675 – 14 September 1749) was a British army officer and Whig politician. After serving as a junior officer under William III during the Williamite War in Ireland and during th ...

, inherited the estate in 1697, and in 1713 was given the title Baron Cobham. During this period, both the house and the garden were redesigned and expanded, with leading architects, designers and gardeners employed to enhance the property.

The installation of a variety of temples and classical features was illustrated the Temple family's wealth and status. The temples are also considered as a humorous reference to the family motto: ''TEMPLA QUAM DILECTA'' ('How beautiful are the Temples').

1690s to 1740s

In the 1690s, Stowe had a modest early

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, plats, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the ...

garden, but it has not survived, as it was altered and adapted as the gardens were progressively remodelled. Within a relatively short time, Stowe became widely renowned for its magnificent gardens created by Lord Cobham. Created in three main phases, the gardens at Stowe show the development of garden design in 18th-century England. They are also the only gardens where

Charles Bridgeman

Charles Bridgeman (1690–1738) was an English garden designer who helped pioneer the naturalistic landscape style. Although he was a key figure in the transition of English garden design from the Anglo-Dutch formality of patterned parterres ...

,

William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, b ...

, and

Capability Brown

Lancelot "Capability" Brown (born c. 1715–16, baptised 30 August 1716 – 6 February 1783) was an English gardener and landscape architect, a notable figure in the history of the English landscape garden style.

Unlike other architects ...

all made significant contributions to the character and design.

From 1711 to 1735,

Charles Bridgeman

Charles Bridgeman (1690–1738) was an English garden designer who helped pioneer the naturalistic landscape style. Although he was a key figure in the transition of English garden design from the Anglo-Dutch formality of patterned parterres ...

was the garden designer, whilst

John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restor ...

was the architect from 1720 until his death in 1726. They designed an

English Baroque

English Baroque is a term used to refer to modes of English architecture that paralleled Baroque architecture in continental Europe between the Great Fire of London (1666) and roughly 1720, when the flamboyant and dramatic qualities of Baroque ...

park, inspired by the work of

George London,

Henry Wise and

Stephen Switzer

Stephen Switzer (1682–1745) was an English gardener, garden designer and writer on garden subjects, often credited as an early exponent of the English landscape garden. He is most notable for his views of the transition between the large garde ...

. After Vanbrugh's death in 1726,

James Gibbs

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was a Scottish architect. Born in Aberdeen, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England. He is an important figure whose work spanned the transition between English Ba ...

took over as garden architect. He also worked in the English Baroque style. Bridgeman was notable for the use of canalised water at Stowe.

In 1731,

William Kent

William Kent (c. 1685 – 12 April 1748) was an English architect, landscape architect, painter and furniture designer of the early 18th century. He began his career as a painter, and became Principal Painter in Ordinary or court painter, b ...

was appointed to work with Bridgeman, whose last designs are dated 1735. After Bridgeman, Kent took over as the garden designer. Kent had already created the noted garden at

Rousham House

Rousham House (also known as Rousham Park) is a English country house, country house at Rousham in Oxfordshire, England. The house, which has been continuously in the ownership of one family, was built circa 1635 and remodelled by William Kent in ...

, and he and Gibbs built temples, bridges, and other garden structures, creating a less formal style of garden. Kent's masterpiece at Stowe is the innovative Elysian Fields, which were "laid out on the latest principles of following natural lines and contours". With its Temple of Ancient Virtue that looks across to his Temple of British Worthies, Kent's architectural work was in the newly fashionable

Palladian style

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

.

In March 1741,

Capability Brown

Lancelot "Capability" Brown (born c. 1715–16, baptised 30 August 1716 – 6 February 1783) was an English gardener and landscape architect, a notable figure in the history of the English landscape garden style.

Unlike other architects ...

was appointed head gardener and he lived in the East Boycott Pavilion. He had first been employed at Stowe in 1740, to support work on the water schemes on site. Brown worked with Gibbs until 1749 and with Kent until the latter's death in 1748. Brown departed in the autumn of 1751 to start his independent career as a garden designer. At that time, Bridgeman's octagonal pond and lake were extended and given a "naturalistic" shape. A Palladian bridge was added in 1744, probably to Gibbs's design. Brown also reputedly contrived a ''Grecian Valley'' which, despite its name, was an abstract composition of landform and woodland.

He also developed the ''Hawkwell Field'', with Gibbs's most notable building, the ''Gothic Temple'', within. The Temple is one of the properties leased from the National Trust by the

Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British architectural conservation, building conservation charitable organization, charity, founded in 1965 by John Smith (Conservative politician), Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or ...

, who maintain it as a holiday home. As

John Claudius Loudon

John Claudius Loudon (8 April 1782 – 14 December 1843) was a Scottish botanist, garden designer and author, born in Cambuslang in 1782. He was the first to use the term arboretum in writing to refer to a garden of plants, especially trees, co ...

remarked in 1831, "nature has done little or nothing; man a great deal, and time has improved his labours".

1740s to 1760s

Earl Temple

Earl Temple, who had inherited Stowe from his uncle Lord Cobham, turned to a garden designer called Richard Woodward after Brown left. Woodward had worked at

Wotton House

Wotton House, Wotton Underwood, Buckinghamshire, England, is a stately home built between 1704 and 1714, to a design very similar to that of the contemporary version of Buckingham House. The house is an example of English Baroque and a Grade I ...

, the Earl's previous home. The work of naturalising the landscape started by Brown was continued under Woodward and was accomplished by the mid-1750s.

At the same time, Earl Temple turned his attention to the various temples and monuments. He altered several temples designed by Vanburgh and Gibbs to make them conform to his taste for

Neoclassical architecture

Neoclassical architecture, sometimes referred to as Classical Revival architecture, is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassicism, Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy, France and Germany. It became one of t ...

. To accomplish this, he employed

Giovanni Battista Borra

Giovanni Battista Borra (27 December 1713 – November 1770) was an Italian architect, engineer and architectural draughtsman.

Life

Borra was born in Dogliani. Studying under Bernardo Antonio Vittone from 1733 to 1736 (producing 10 plates for h ...

from July 1750 to c. 1760. Also at this time, several statues and temples were relocated within the garden, including the Fane of Pastoral Poetry.

Earl Temple made further alterations in the gardens from the early 1760s, with alteration to both planting and structure. Several older structures were removed, including the Witch House. Several designs for this period are attributed to his cousin

Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford

Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford (3 March 1737 – 19 January 1793) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 until 1784 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Camelford. He was an art connoisseur.

Early life

Pit ...

. Camelford's most notable design was the Corinthian Arch.

1770s To Present

Famed as a highly fashionable garden, by 1777 some visitors, such as

Henry Temple, 2nd Viscount Palmerston

Henry Temple, 2nd Viscount Palmerston, FRS (4 December 1739 – 17 April 1802), was a British politician.

Life

Temple was a son of Henry Temple (son of Henry Temple, 1st Viscount Palmerston) and Jane, daughter of Sir John Barnard, Lord Mayor o ...

, complained that the gardens were "much behind the best modern ones in points of good taste".

The next owner of Stowe, the

Marquess of Buckingham

Marquess of Buckingham was a title that has been created two times in the peerages of England and Great Britain.

The first creation of the marquessate was in 1618 for George Villiers, a favourite of James I of England. He had previously been ...

, made relatively few changes to the gardens, as his main contribution to the Stowe scheme was the completion of Stowe House's interior.

Vincenzo Valdrè was his architect and built a few new structures such as The Menagerie, with its formal garden and the Buckingham Lodges at the southern end of the Grand Avenue, and most notably the Queen's Temple.

19th-century Stowe

The last significant changes to the gardens were made by the next two owners of Stowe, the 1st and 2nd

Dukes of Buckingham and Chandos

Duke of Buckingham, referring to the market town of Buckingham, England, is an extinct title that has been created several times in the peerages of Peerage of England, England, Peerage of Great Britain, Great Britain, and the Peerage of the Uni ...

. The former succeeded in buying the Lamport Estate in 1826, which was immediately to the east of the gardens, adding to the south-east of the gardens to form the Lamport Gardens.

From 1840 the

2nd Duke's gardener Mr Ferguson created rock structures and water features in the new Lamport Gardens. The architect

Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

Blore was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's backg ...

was also employed to build the Lamport Lodge and Gates as a carriage entrance, and also remodelled the Water Stratford Lodge at the start of the Oxford Avenue.

In 1848 the 2nd Duke was forced to sell the contents of the house and a large part of the estate in order to begin to pay off his debts. The auction by

Christie's

Christie's is a British auction house founded in 1766 by James Christie (auctioneer), James Christie. Its main premises are on King Street, St James's in London, and it has additional salerooms in New York, Paris, Hong Kong, Milan, Geneva, Shan ...

made the name of the auction house. In 1862,

returned to Stowe and began to repair several areas of the gardens, including planting avenues of trees. In 1868 the garden was re-opened to the public.

20th century

The remaining estate was sold in 1921 and 1922. In 1923,

Stowe School

The Stowe School is a public school (English private boarding school) for pupils aged 13–18 in the countryside of Stowe, England. It was opened on 11 May, 1923 at Stowe House, a Grade I Heritage Estate belonging to the British Crown. ...

was founded, which saved the house and garden from destruction. Until 1989, the landscape garden was owned by Stowe School, who undertook some restoration work. This included the development of a restoration plan in the 1930s. The first building to be restored was the Queen's Temple, repairs to which were funded by a public appeal launched by the future

Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

. In the 1950s, repairs were made to the Temple of Venus, the Corinthian Arch and the Rotondo. Stowe Avenue was replanted in 1960.

In the 1960s, significant repairs were made to buildings such as the Lake Pavilions and the Pebble Alcove. Other works included replanting several avenues, repairs to two-thirds of the buildings, and the reclamation of six of the lakes (only the Eleven Acre Lake was not tackled). As a result of this, the school was recognised for its contribution to conservation and heritage with awards in 1974 and 1975.

The

National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

first became significantly involved in Stowe in 1965, when John Workman was invited to compile a plan for restoration. In 1967, 221 acres were covenanted to the National Trust and in 1985 the trust purchased Oxford Avenue, the first time it had bought land to enhance a site not under its ownership. In 1989, much of the garden and the park was donated to the National Trust, after generous donations from the

National Heritage Memorial Fund

The National Heritage Memorial Fund (NHMF) was set up in 1980 to save the most outstanding parts of the British national heritage, in memory of those who have given their lives for the UK. It replaced the National Land Fund, which had fulfilled t ...

and an anonymous benefactor, which enabled an endowment for repairs to be created. In 1993, the National Trust successfully completed an appeal for £1 million, with the aim of having the garden restored by 2000. Parallel to fund-raising, extensive garden, archaeological and biological surveys were undertaken. Further repairs were undertaken to many monuments in the 1990s. The ''Stowe Papers'', some 350,000 documents relating to the estate, are in the collection of the

Huntington Library

The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, known as The Huntington, is a collections-based educational and research institution established by Henry E. Huntington and Arabella Huntington in San Marino, California, United State ...

.

21st century

In 2012 the restoration of the historic New Inn was finished, providing enhanced visitor services. In 2015, the National Trust began a further programme of restoration, which included the recreation of the Queens Theatre, the return of many statues to former locations in the Grecian Valley, and the return of the Temple of Modern Virtue to the Elysian Fields.

Accommodating the requirements of a 21st-century school within a historic landscape continues to create challenges. In the revised ''Buckinghamshire'', in the

Pevsner Buildings of England series published in 2003, Elizabeth Williamson wrote of areas of the garden being "disastrously invaded by school buildings". In 2021, plans for a new Design, Technology and Engineering block in Pyramid Wood provoked controversy. The school's plans were supported by the National Trust but opposed by

Buckinghamshire County Council

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshire to the east, Greater London ...

's own planning advisors, as well as a range of interest groups including

The Gardens Trust

The Gardens Trust (formerly the Garden History Society) is a national membership organisation in the United Kingdom established to study the history of gardening and to protect historic gardens.

It is a registered charity with headquarters in Lo ...

. Despite objections from the council's independent advisor, and an appeal to the

Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

The secretary of state for culture, media and sport, also referred to as the culture secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for strategy and policy across the Department for Cultu ...

, the plans were approved in 2022.

Layout

Approaching Stowe Gardens

In 2012, with the renovation and re-opening of the New Inn, visitors to Stowe Gardens have returned to using the historic entrance route to the site which was used by tourists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Most will drive between the Buckingham Lodges, before approaching the site along the Grand Avenue and turning right in front of the Corinthian Arch.

Significant monuments on the route in, include:

The Buckingham Lodges

The Buckingham Lodges are 2.25 miles south-southeast of the centre of the House. Probably designed by

Vincenzo Valdrè and dated 1805, they flank the southern entrance to the Grand Avenue.

The Grand Avenue

The Grand Avenue, from

Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

to the south and the Oxford Avenue from the south-west, which leads to the forecourt of the house. The Grand Avenue was created in the 1770s; it is in width and one and half miles in length, and was lined originally with

elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

trees. The elms succumbed in the 1970s to

Dutch elm disease and were replaced with alternate

beech

Beech (genus ''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to subtropical (accessory forest element) and temperate (as dominant element of Mesophyte, mesophytic forests) Eurasia and North America. There are 14 accepted ...

&

chestnut

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

Description

...

trees.

The Corinthian Arch

Designed in 1765 by

Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford

Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford (3 March 1737 – 19 January 1793) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 until 1784 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Camelford. He was an art connoisseur.

Early life

Pit ...

, Lord Temple's cousin, the arch is built from stone and is in height and wide. It is modelled on ancient Roman

triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road, and usually standing alone, unconnected to other buildings. In its simplest form, a triumphal ...

es. This is located at the northern end of the Grand Avenue 0.8 miles south-southeast of the centre of the House and is on the top of a hill. The central arch is flanked on the south side by paired

Corinthian pilaster

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

s and on the north side by paired Corinthian

engaged column

An engaged column is an architectural element in which a column is embedded in a wall and partly projecting from the surface of the wall, which may or may not carry a partial structural load. Sometimes defined as semi- or three-quarter detached ...

s. The arch contains two four-storey residences. The flanking

Tuscan columns were added in 1780.

The New Inn

Situated about to the east of the Corinthian Arch, the inn was built in 1717 specifically to provide accommodation for visitors to the gardens. It was expanded and rebuilt in several phases. The inn housed a small brewery, a farm and dairy. It closed in the 1850s, then being used as a farm,

smithy and

kennels

A kennel is a structure or shelter for dogs. Used in the plural, ''the kennels'', the term means any building, collection of buildings or a property in which dogs are housed, maintained, and (though not in all cases) bred. A kennel can be made o ...

for deer hounds.

The building was purchased in a ruinous condition by the National Trust in 2005. In 2010, work started on converting it into the new

visitor centre

A visitor center or centre (see American and British English spelling differences), visitor information center or tourist information centre is a physical location that provides information to tourists.

Types

A visitor center may be a Civic c ...

. Since 2011, this has been the entrance for visitors to the gardens. Visitors had formerly used the Oxford Gates. The New Inn is linked by the Bell Gate Drive to the Bell Gate next to the eastern Lake Pavilion, so called because visitors used to have to ring the bell by the gate to gain admittance to the property.

Ha-ha

The main gardens, enclosed within the

ha-ha

A ha-ha ( or ), also known as a sunk fence, blind fence, ditch and fence, deer wall, or foss, is a recessed landscape design element that creates a vertical barrier (particularly on one side) while preserving an uninterrupted view of the lan ...

s (sunken or trenched fences) over four miles (6 km) in length, cover over .

Gallery of features when approaching Stowe

File:Buckingham or Stowe Lodges - geograph.org.uk - 3097738.jpg, The Buckingham Lodges

File:Stowe Avenue - geograph.org.uk - 154586.jpg, The Grand Avenue looking north towards the Corinthian Arch and Buckingham

File:Stowe Corinthian Arch.jpg, The Corinthian Arch

File:Arch of New Inn at Stowe - geograph.org.uk - 3195569.jpg, The New Inn

File:The ha-ha, Stowe - geograph.org.uk - 886732.jpg, The ha-ha that surrounds the park

File:Octagon Lake with Stowe House, Stowe - Buckinghamshire, England - DSC06849.jpg, Octagon Lake with Stowe House

Octagon Lake

One of the first areas of the garden that visitors may encounter is the Octagon Lake and the features associated with it. The lake was originally designed as a formal octagonal pool, with sharp corners, as part of the seventeenth century formal gardens. Over the years, the shape of the pond was softened, gradually harmonising it within Stowe's increasingly naturalistic landscape.

Monuments and structures in this area include:

The Chatham Urn

This is a copy of the large stone

urn

An urn is a vase, often with a cover, with a typically narrowed neck above a rounded body and a footed pedestal. Describing a vessel as an "urn", as opposed to a vase or other terms, generally reflects its use rather than any particular shape ...

known as the

Chatham Vase

__NOTOC__

The Chatham Vase is a stone sculpture by John Bacon commissioned as a memorial to William Pitt the Elder by his wife, Hester, Countess of Chatham. It was originally erected at their house in Burton Pynsent in 1781. It was subsequently ...

carved in 1780 by

John Bacon. It was placed in 1831 on a small island in the Octagon Lake. It is a memorial to

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British people, British British Whig Party, Whig politician, statesman who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him "Chatham" or "Pit ...

former prime minister, who was a relative of the Temple family. The original was sold in 1848 and is now at

Chevening

Chevening House () is a large country house in the parish of Chevening in Kent, England. Built between 1617 and 1630 to a design reputedly by Inigo Jones and greatly extended after 1717, it is a Grade I listed building. The surrounding gardens, ...

House.

Congreve's Monument

Built of stone designed by Kent in 1736, this is a memorial to the playwright

William Congreve

William Congreve (24 January 1670 – 19 January 1729) was an English playwright, satirist, poet, and Whig politician. He spent most of his career between London and Dublin, and was noted for his highly polished style of writing, being regard ...

. It is in the form of a pyramid with an urn carved on one side with

Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

's head,

pan pipes

A pan flute (also known as panpipes or syrinx) is a musical instrument based on the principle of the closed tube, consisting of multiple pipes of gradually increasing length (and occasionally girth). Multiple varieties of pan flutes have been ...

and masks of comedy and tragedy; the truncated pyramid supports the sculpture of an

ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a superfamily of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and Europe in prehistory, and counting humans are found global ...

looking at itself in a mirror, beneath are these inscriptions:

The Lake Pavilions

These pavilions have moved location during their history. They were designed by Vanbrugh in 1719, they are on the edge of the

ha-ha

A ha-ha ( or ), also known as a sunk fence, blind fence, ditch and fence, deer wall, or foss, is a recessed landscape design element that creates a vertical barrier (particularly on one side) while preserving an uninterrupted view of the lan ...

flanking the central vista through the park to the Corinthian Arch. They were moved further apart in 1764 and their details made

neo-classical by the architect Borra. Raised on a low podium they are reached by a flight of eight steps, they are pedimented of four fluted Doric columns in width by two in depth, with a solid back wall and with

coffer

A coffer (or coffering) in architecture is a series of sunken panels in the shape of a square, rectangle, or octagon in a ceiling, soffit or vault.

A series of these sunken panels was often used as decoration for a ceiling or a vault, al ...

ed plaster ceiling. Behind the eastern pavilion is the ''Bell Gate''. This was used by the public when visiting the gardens in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Artificial Ruins and Cascade

Constructed in the 1730s, the

cascade

Cascade, or Cascading may refer to:

Science and technology Science

* Air shower (physics), a cascade (particle shower) of subatomic particles and ionized nuclei

** Particle shower, a cascade of secondary particles produced as the result of a high ...

links the Eleven Acre Lake with the Octagon Lake as the former was elevated. The ruins are a series of arches above the cascade purposefully built to look ruinous.

The Wooden Bridge

This crosses the mouth of the River Styx where it emptied into the Octagon Lake. Rebuilt in 2012 by the National Trust in oak, it recreates a long lost bridge.

The Pebble Alcove

Built of stone before 1739 probably to the designs of Kent. It takes the form of an

exedra

An exedra (: exedras or exedrae) is a semicircular architecture, architectural recess or platform, sometimes crowned by a semi-dome, and either set into a building's façade or free-standing. The original Greek word ''ἐξέδρα'' ('a seat ou ...

enclosed by a stone work surmounted by a pediment. The exedra is decorated with coloured pebbles, including the family coat of arms below which is the Temple family motto ''TEMPLA QUAM DELECTA'' (How Beautiful are thy Temples).

Gallery of features near the Octagon Lake

File:Octagon Lake with Lord Chatham's Urn, Stowe - Buckinghamshire, England - DSC06855.jpg, The Chatham Urn

File:Stowe, The Congreve Monument (geograph 3577611).jpg, Congreve's Monument

File:Western Lake Pavilion, Stowe - geograph.org.uk - 835336.jpg, The Western Lake Pavilion

File:Stowe Octagon Lake.jpg, The Artificial Ruins and Cascade

File:Wooden Bridge, Stowe Gardens.jpg, Wooden Bridge

File:Pebble Alcove, Stowe - Buckinghamshire, England - DSC06776.jpg, The Pebble Alcove

South Vista

The south vista includes the tree-flanked sloping lawns to the south of the House down to the Octagon Lake and a mile and a half beyond to the Corinthian Arch beyond which stretches the Grand Avenue of over a mile and a half to

Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

. This is the oldest area of the gardens. There were walled gardens on the site of the south lawn from the 1670s that belonged to the old house. These gardens were altered in the 1680s when the house was rebuilt on the present site. They were again remodelled by Bridgeman from 1716. The lawns with the flanking woods took on their current character from 1741 when 'Capability' Brown re-landscaped this area.

The buildings in this area are:

The Doric Arch

Built of stone erected in 1768 for the visit of

Princess Amelia, probably to the design of Thomas Pitt, 1st Baron Camelford, is a simple arch flanked by fluted

Doric pilasters, with an elaborate entablature with

triglyph

Triglyph is an architectural term for the vertically channeled tablets of the Doric frieze in classical architecture, so called because of the angular channels in them. The rectangular recessed spaces between the triglyphs on a Doric frieze are ...

s and carved

metopes supporting a tall attic. This leads to the Elysian fields.

Apollo and the Nine Muses

Arranged in a semicircle near the Doric Arch there used to be statues of

Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

and the

Nine Muses removed sometime after 1790. These sculptures were created by

John Nost

John Nost ( Dutch: Jan van Nost) (died 1729) was a Flemish sculptor who worked in England in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Life

Originally from Mechelen in what is now Belgium, he moved to England in the second half of the 17th cent ...

and were originally positioned along the south vista. In 2019 the ten plinths 5 each side of the ''Doric Arch'' were recreated, and statues of the Nine Muses placed on them.

Statue of George II

On the western edge of the lawn, the statue was rebuilt in 2004 by the National Trust.

This is a monument to King

George II, originally built in 1724 before he became king. The monument consists of an unfluted Corinthian column on a plinth over high that supports the Portland stone sculpture of the King which is a copy of the statue sold in 1921.

The pillar has this inscription from

Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), Suetonius, Life of Horace commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). Th ...

's Ode 15, Book IV:

The Elysian fields

The Elysian Fields is an area to the immediate east of the South Vista; designed by William Kent, work started on this area of the gardens in 1734. The area covers about . It consists of a series of buildings and monuments surrounding two narrow lakes, called the ''River

Styx

In Greek mythology, Styx (; ; lit. "Shuddering"), also called the River Styx, is a goddess and one of the rivers of the Greek Underworld. Her parents were the Titans Oceanus and Tethys, and she was the wife of the Titan Pallas and the moth ...

'', which step down to a branch of ''the Octagon Lake''. The banks are planted with deciduous and evergreen trees. The adoption of the name alludes to

Elysium

Elysium (), otherwise known as the Elysian Fields (, ''Ēlýsion pedíon''), Elysian Plains or Elysian Realm, is a conception of the afterlife that developed over time and was maintained by some Greek religious and philosophical sects and cult ...

, and the monuments in this area are to the 'virtuous dead' of both Britain and

ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

.

The buildings in this area are:

St Mary's Church

In the woods between the House and the Elysian Fields is Stowe

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

. This is the only surviving structure from the old village of Stowe. Dating from the 14th century, the building consists of a

nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

with

aisle

An aisle is a linear space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, in buildings such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parliaments, courtrooms, ...

s and a west tower, a

chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

with a chapel to the north and an east window c. 1300 with

reticulated

Reticulation is a net-like pattern, arrangement, or structure.

Reticulation or Reticulated may refer to:

* Reticulation (single-access key), a structure of an identification tree, where there are several possible routes to a correct identificat ...

tracery

Tracery is an architectural device by which windows (or screens, panels, and vaults) are divided into sections of various proportions by stone ''bars'' or ''ribs'' of moulding. Most commonly, it refers to the stonework elements that support th ...

.

Lancelot "Capability" Brown was married in the church in 1744. The church contains a fine

Laurence Whistler

Sir Alan Charles Laurence Whistler (21 January 1912 – 19 December 2000) was a British glass engraver and poet. He was both the first President of the British Guild of Glass Engravers and the first recipient of the King's Gold Medal for Poe ...

etched glass window in memory of The Hon. Mrs. Thomas Close-Smith of Boycott Manor, eldest daughter of the

11th Lady Kinloss

In music theory, an eleventh is a compound interval consisting of an octave plus a fourth.

A perfect eleventh spans 17 and the augmented eleventh 18 semitones, or 10 steps in a diatonic scale.

Since there are only seven degrees in a diaton ...

, who was the eldest daughter of the

3rd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos. Thomas Close-Smith himself was the

High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire

The High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire, in common with other counties, was originally the King's representative on taxation upholding the law in Saxon times. The word Sheriff evolved from 'shire-reeve'.

Sheriff is the oldest secular office under th ...

in 1942, and died in 1946. Caroline Mary, his wife, known as May, died in 1972.

The Temple of Ancient Virtue

Built in 1737 to the designs of Kent, in the form of a

Tholos, a circular domed building surrounded by columns. In this case they are unfluted Ionic columns, 16 in number, raised on a podium. There are twelve steps up to the two arched doorless entrances. Above the entrances are the words ''Priscae virtuti'' (to Ancient Virtue). Within are four niches one between the two doorways. They contain four life size sculptures (plaster copies of the originals by

Peter Scheemakers

Peter Scheemakers or Pieter Scheemaeckers II or the Younger (10 January 1691 – 12 September 1781) was a Southern Netherlands, Flemish sculptor who worked for most of his life in London. His public and church sculptures in a classicism, classici ...

paid for in 1737, they were sold in 1921). They are

Epaminondas

Epaminondas (; ; 419/411–362 BC) was a Greeks, Greek general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek polis, city-state of Thebes, Greece, Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a pre ...

(general),

Lycurgus

Lycurgus (; ) was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, credited with the formation of its (), involving political, economic, and social reforms to produce a military-oriented Spartan society in accordance with the Delphic oracle. The Spartans i ...

(lawmaker),

Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

(poet) and

Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

(philosopher).

The Temple of British Worthies

Designed by Kent and built 1734–1735. Built of stone, it is a curving roofless

exedra

An exedra (: exedras or exedrae) is a semicircular architecture, architectural recess or platform, sometimes crowned by a semi-dome, and either set into a building's façade or free-standing. The original Greek word ''ἐξέδρα'' ('a seat ou ...

with a large stone pier in the centre surmounted by a stepped pyramid containing an oval niche that contains a bust of

Mercury, a copy of the original. The curving wall contains six

niches either side of the central pier, with further niches on the two ends of the wall and two more behind. At the back of the Temple is a chamber with an arched entrance, dedicated to Signor Fido, a greyhound.

The niches are filled by

busts, half of which were carved by

John Michael Rysbrack

Johannes Michel or John Michael Rysbrack, original name Jan Michiel Rijsbrack, often referred to simply as Michael Rysbrack (24 June 1694 – 8 January 1770), was an 18th-century Flemish sculptor, who spent most of his career in England where h ...

for a previous building in the gardens. They portray

John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

,

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

,

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, Sir

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, Sir

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

,

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

,

William III William III or William the Third may refer to:

Kings

* William III of Sicily ()

* William III of England and Ireland or William III of Orange or William II of Scotland (1650–1702)

* William III of the Netherlands and Luxembourg (1817–1890)

N ...

and

Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was an English architect who was the first significant Architecture of England, architect in England in the early modern era and the first to employ Vitruvius, Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmet ...

. The other eight are by

Peter Scheemakers

Peter Scheemakers or Pieter Scheemaeckers II or the Younger (10 January 1691 – 12 September 1781) was a Southern Netherlands, Flemish sculptor who worked for most of his life in London. His public and church sculptures in a classicism, classici ...

, which were commissioned especially for the Temple. These represent

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early ...

, Sir

Thomas Gresham

Sir Thomas Gresham the Elder (; c. 151921 November 1579) was an English merchant and financier who acted on behalf of King Edward VI (1547–1553) and Edward's half-sisters, queens Mary I (1553–1558) and Elizabeth I (1558–1603). In 1565 Gr ...

, King

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

,

Edward, the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), known as the Black Prince, was the eldest son and heir apparent of King Edward III of England. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II of England, Richard II, succession to the Br ...

, Sir

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebell ...

, Sir

Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

,

John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English politician from Oxfordshire, who was killed fighting for Roundhead, Parliament in the First English Civil War. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and a cousin of Oliver Cromwell, he was one of ...

and Sir

John Barnard

John Edward Barnard, (born 4 May 1946) is an English engineer and racing car designer. Barnard is credited with the introduction of two new designs into Formula One: the carbon fibre composite chassis first seen in with McLaren, and the sem ...

(

Whig MP and opponent of the Whig Prime Minister Sir

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

).

The choice of who was considered a 'British Worthy' was very much influenced by the Whig politics of the family, the chosen individuals falling into two groups, eight known for their actions and eight known for their thoughts and ideas. The only woman to be included was Elizabeth I. The inscription above her bust, which praises her leadership, reads:

The Shell Bridge

Designed by Kent, and finished by 1739, is actually a dam disguised as a bridge of five arches and is decorated with shells.

The Grotto

Probably designed by Kent in the 1730s, is located at the head of the serpentine 'river Styx' that flows through the Elysian Fields. There are two pavilions, one ornamented with shells the other with pebbles and flints. In the central room is a circular recess in which are two basins of white marble. In the upper is a marble statue of Venus rising from her bath, and water falls from the upper into the lower basin, there passing under the floor to the front, where it falls into the river Styx. A tablet of marble is inscribed with these lines from

John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

:

The Seasons Fountain

Probably erected in 1805, built from white statuary marble. Spring water flows from it, and the basic structure appears to be made from an 18th-century chimneypiece. It used to be decorated with

Wedgwood

Wedgwood is an English China (material), fine china, porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer that was founded on 1 May 1759 by the potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood and was first incorporated in 1895 as Josiah Wedgwood and Sons L ...

plaques of the four seasons and had silver drinking cups suspended on either side. it was the first structure to be reconstructed under National Trust ownership.

The Grenville Column

Originally erected in 1749 near the Grecian Valley, it was moved to its present location in 1756; Earl Temple probably designed it. It commemorates one of Lord Cobham's nephews, Captain

Thomas Grenville

Thomas Grenville (31 December 1755 – 17 December 1846) was a British politician and bibliophile.

Background and education

Grenville was the second son of Prime Minister George Grenville and Elizabeth Wyndham, daughter of Sir William Wyn ...

RN. He was killed in 1747 while fighting the French off

Cape Finisterre

Cape Finisterre (, also ; ; ) is a rock-bound peninsula on the west coast of Galicia, Spain.

In Roman times it was believed to be an end of the known world. The name Finisterre, like that of Finistère in France, derives from the Latin , mean ...

aboard HMS ''

Defiance

Defiance may refer to:

Film, television and theatre

* ''Defiance'' (1952 film), a Swedish drama film directed by Gustaf Molander

* ''Defiance'' (1980 film), an American crime drama starring Jan-Michael Vincent

* ''Defiance'' (2002 film), a ...

'' under the command of

Admiral Anson.

The monument is based on an

Ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

naval monument, a

rostral column

A rostral column is a type of victory column originating in ancient Greece and Rome, where they were erected to commemorate a naval military victory. Its defining characteristic is the integrated prows or Naval ram, rams of ships, representing ...

, one that is carved with the prows of Roman galleys sticking out from the shaft. The order used is Tuscan, and is surmounted by a statue of

Calliope

In Greek mythology, Calliope ( ; ) is the Muse who presides over eloquence and epic poetry; so called from the ecstatic harmony of her voice. Hesiod and Ovid called her the "Chief of all Muses".

Mythology

Calliope had two famous sons, OrpheusH ...

holding a scroll inscribed ''Non nisi grandia canto'' (Only sing of heroic deeds); there is a lengthy inscription in Latin added to the base of the column after it was moved.

The Cook Monument

Built in 1778 as a monument to Captain

James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

; it takes the form of a stone globe on a pedestal. It was moved to its present position in 1842. The pedestal has a carved relief of Cook's head in profile and the inscription ''Jacobo Cook/MDCCLXXVIII''.

The Gothic Cross

Erected in 1814 from

Coade stone

Coade stone or ''Lithodipyra'' or ''Lithodipra'' () is stoneware that was often described as an artificial stone in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was used for moulding neoclassical architecture, neoclassical statues, a ...

on the path linking the Doric Arch to the Temple of Ancient Virtue. It was erected by the 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos as a memorial to his mother Lady Mary Nugent. It was demolished in the 1980s by a falling

elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

tree. The National Trust rebuilt the cross in 2016 using several of the surviving pieces of the monument.

The Marquess of Buckingham's Urn

Sited behind the Temple of British Worthies, erected in 1814 by the 1st Duke in memory of his father, the urn was moved to the school precincts in 1931. A replica urn was created and erected in 2018.

Gallery of features around the Elysian fields

File:Saint Mary's Church, Stowe - Buckinghamshire, England - DSC07257.jpg, Saint Mary's Church

File:Temple of Ancient Virtue, Stowe - geograph.org.uk - 886691.jpg, The Temple of Ancient Virtue

File:The Temple of British Worthies - 2 - geograph.org.uk - 2472777.jpg, The Temple of British Worthies

File:Epitaph to Signior Fido, Temple of British Worthies.jpg, Epitaph to Signior Fido at the rear of the Temple of British Worthies

File:Shell Bridge, Stowe - Buckinghamshire, England - DSC07359.jpg, The Shell Bridge

File:Grotto, Stowe - Buckinghamshire, England - DSC07337.jpg, Looking out from the Grotto

File:Stowe Park, Buckinghamshire (4664647926).jpg, The Seasons Fountain

File:Captain Grenville's Column, Stowe Landscape Gardens - geograph.org.uk - 837884.jpg, The Grenville Column

File:Captain Cook's Monument, Stowe - geograph.org.uk - 886624.jpg, The Cook Monument

Hawkwell Field

Hawkwell Field lies to the east of the Elysian Fields, and is also known as ''The Eastern Garden''. This area of the gardens was developed in the 1730s & 1740s, an open area surrounded by some of the larger buildings all designed by

James Gibbs

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was a Scottish architect. Born in Aberdeen, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England. He is an important figure whose work spanned the transition between English Ba ...

.

The buildings in this area are:

The Queen's Temple

Originally designed by Gibbs in 1742 and was then called the ''Lady's Temple''.

This was designed for Lady Cobham to entertain her friends. But the building was extensively remodelled in 1772–1774 to give it a neo-classical form.

Further alterations were made in 1790 by Vincenzo Valdrè. These commemorated the recovery of

George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

from madness with the help of Queen

Charlotte

Charlotte most commonly refers to:

*Charlotte (given name), a feminine form of the given name Charles

** Princess Charlotte (disambiguation)

** Queen Charlotte (disambiguation)

*Charlotte, North Carolina, United States, a city

* Charlotte (cake) ...

after whom the building was renamed.

The main floor is raised up on a podium, the main façade consists of a portico of four fluted

Composite

Composite or compositing may refer to:

Materials

* Composite material, a material that is made from several different substances

** Metal matrix composite, composed of metal and other parts

** Cermet, a composite of ceramic and metallic material ...

columns, these are approached by a balustraded flight of steps the width of the portico. The façade is wider than the portico, the flanking walls having niches containing ornamental urns. The large door is fully glazed.

The room within is the most elaborately decorated of any of the garden's buildings. The

Scagliola

Scagliola (from the Italian language, Italian ''scaglia'', meaning "chips") is a type of fine plaster used in architecture and sculpture. The same term identifies the technique for producing columns, sculptures, and other architectural elements t ...

Corinthian columns and pilasters are based on the

Temple of Venus and Roma

The Temple of Venus and Roma (Latin: ''Aedes Veneris et Romae'') is thought to have been the largest Roman temple, temple in Ancient Rome. Located on the Velian Hill, between the eastern edge of the Forum Romanum and the Colosseum, it was dedicat ...

, the barrel-vaulted ceiling is coffered. There are several plaster medallions around the walls, including:

Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

Deject, with this inscription ''Desideriis icta fidelibus Quaerit Patria Caesarem'' (For Caesar's life, with anxious hopes and fears Britannia lifts to Heaven a nation's tears); Britannia with a palm branch sacrificing to

Aesculapius with this inscription ''O Sol pulcher! O laudande, Canam recepto Caesare felix'' (Oh happy days! with rapture Britons sing the day when Heavenrestore their favourite King!); Britannia supporting a medallion of the Queen with the inscription ''Charlottae Sophiae Augustae, Pietate erga Regem, erga Rempublicam Virtute et constantia, In difficillimis temporibus spectatissimae D.D.D. Georgius M. de Buckingham MDCCLXXXIX''. (To the Queen, Most respectable in the most difficult moments, for her attachment and zeal for the public service, George Marquess of Buckingham dedicates this monument).

Other plaster decoration on the walls includes: 1. Trophies of Religion, Justice and Mercy, 2. Agriculture and Manufacture, 3. Navigation and Commerce and 4. War.

Almost all the decoration was the work of Charles Peart except for the statue of

Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

by

Giuseppe Ceracchi

Giuseppe Ceracchi, also known as ''Giuseppe Cirachi'', (4 July 1751 – 30 January 1801) was an Italian sculptor active in a Neoclassic style. He worked in Italy, England, and in the United States following the nation's emergence following the Am ...

.

In 1842 the 2nd Duke of Buckingham inserted in the centre of the floor the Roman

mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

found at nearby

Foscott.

The Temple has been used for over 40 years by the school as its Music School.

The Gothic Temple

Designed by

James Gibbs

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was a Scottish architect. Born in Aberdeen, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England. He is an important figure whose work spanned the transition between English Ba ...

in 1741 and completed about 1748, the Gothic Temple is the gardens' only building of

ironstone

Ironstone is a sedimentary rock, either deposited directly as a ferruginous sediment or created by chemical replacement, that contains a substantial proportion of an iron ore compound from which iron (Fe) can be smelted commercially.

Not to be c ...

; all the others use a creamy-yellow

limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

. The two-storey building is triangular in plan, with a pentagonal tower at each corner: one rises two floors higher than the main building, while the others have lanterns on their roofs. Above the door is a quote from

Pierre Corneille

Pierre Corneille (; ; 6 June 1606 – 1 October 1684) was a French tragedian. He is generally considered one of the three great 17th-century French dramatists, along with Molière and Racine.

As a young man, he earned the valuable patronage ...

's play ''Horace'': "''Je rends grace aux Dieux de n'estre pas Roman''" (I thank the gods I am not a Roman).

The interior includes a circular room of two storeys covered by a shallow dome that is painted to mimic mosaic work including shields representing the

Heptarchy

The Heptarchy was the division of Anglo-Saxon England between the sixth and eighth centuries into petty kingdoms, conventionally the seven kingdoms of East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. The term originated wi ...

. Dedicated 'To the Liberty of our Ancestors'. To quote

John Martin Robinson

John Martin Robinson FSA (born 1948) is a British architectural historian and officer of arms.

Biography

He was born in Preston, Lancashire, and educated at Fort Augustus Abbey, a Benedictine school in Scotland, the University of St Andrews ...

: 'to the Whigs,

Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

and Gothic were interchangeably associated with freedom and ancient English liberties:

trial by jury

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial, in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are increasingly used ...

(erroneously thought to have been founded by King Alfred at a moot on Salisbury Plain),

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter"), sometimes spelled Magna Charta, is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardin ...

, parliamentary representation, all the things which the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

and

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

had protected from the wiles of

Stuart

Stuart may refer to:

People

*Stuart (name), a given name and surname (and list of people with the name)

* Clan Stuart of Bute, a Scottish clan

*House of Stuart, a royal house of Scotland and England

Places Australia Generally

*Stuart Highway, ...

would-be

absolutism, and to the preservation of which Lord Cobham and his 'Patriots' were seriously devoted.

The Temple was used in the 1930s by the school as the

Officer Training Corps

The University Officers' Training Corps (UOTC), also known as the Officers' Training Corps (OTC), are British Army reserve units, under the command of the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, which recruit exclusively from universities and focus on ...

armoury. It is now available as a holiday let through the

Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British architectural conservation, building conservation charitable organization, charity, founded in 1965 by John Smith (Conservative politician), Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or ...

.

The Temple of Friendship

Built of stone in 1739 to the designs of Gibbs. It is located in the south-east corner of the garden. Inscribed on the exterior of the building is AMICITIAE S (sacred to friendship). It was badly damaged by fire in 1840 and remains a ruin.

Built as a pavilion to entertain Lord Cobham's friends it was originally decorated with

mural

A mural is any piece of Graphic arts, graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' ...

s by Francesco Sleter including on the ceiling

Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

, the walls having

allegorical

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory throughou ...

paintings symbolising friendship, justice and liberty. There was a series of ten white marble busts on black marble pedestals around the walls of Cobham (this bust with that of Lord Westmoreland is now in the V&A Museum) and his friends:

Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales (Frederick Louis, German: ''Friedrich Ludwig''; 31 January 1707 – 31 March 1751) was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Queen C ...

;

Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield

Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield (22 September 169424 March 1773) was a British statesman, diplomat, man of letters, and an acclaimed wit of his time.

Early life

He was born in London to Philip Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Chesterfie ...

;

George Lyttelton, 1st Baron Lyttelton

George Lyttelton, 1st Baron Lyttelton, (17 January 1709 – 22 August 1773), known between 1751 and 1756 as Sir George Lyttelton, 5th Baronet, was a British Politician, statesman. As an author himself, he was also a supporter of other writers a ...

;

Thomas Fane, 8th Earl of Westmorland

Thomas Fane, 8th Earl of Westmorland (March 1701 – 25 November 1771) was an English politician and peer. He was an ancestor of the writer George Orwell.

Biography

Thomas Fane was the second son of Henry Fane of Brympton d'Evercy in Somerse ...

; William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham;

Allen Bathurst, 1st Earl Bathurst

Allen Bathurst, 1st Earl Bathurst, (16 November 168416 September 1775), of Bathurst in the County of Sussex, known as The Lord Bathurst from 1712 to 1772, was a British Tory politician. Bathurst sat in the English and British House of Commons ...

; Richard Grenville-Temple, 2nd Earl Temple;

Alexander Hume-Campbell, 2nd Earl of Marchmont

Alexander Hume-Campbell, 2nd Earl of Marchmont (1675 – 27 February 1740), was a Scottish nobleman, politician and judge.

Life

The third but eldest surviving son of Patrick Hume, 1st Earl of Marchmont, by his spouse Grisel (d.1703), daughter ...

;

John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower

John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower, PC (10 August 1694 – 25 December 1754) was a British Tory politician who served as Lord Privy Seal from 1742 to 1743 and again from 1744 to 1754. Leveson-Gower also served in the Parliament of Great Brita ...

. Dated 1741, three were carved by Peter Scheemakers: Cobham, Prince Frederick & Lord Chesterfield, the rest were carved by

Thomas Adye

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

. All the busts were sold in 1848.

The building consisted of a square room rising through two floors surmounted by a pyramidal roof with a lantern. The front has a

portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

of four

Tuscan columns supporting a pediment, the sides have

arcades of one arch deep by three wide also supporting pediments. The arcades and portico with the wall behind are still standing.

The Palladian Bridge

This is a copy of the bridge at

Wilton House

Wilton House is an English country house at Wilton near Salisbury in Wiltshire, which has been the country seat of the Earls of Pembroke for over 400 years. It was built on the site of the medieval Wilton Abbey. Following the dissolution ...

in

Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

, which was itself based in a design by

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be on ...

. The main difference from the Wilton version, which is a footbridge, is that the Stowe version is designed to be used by horse-drawn carriages so is set lower with shallow ramps instead of steps on the approach. It was completed in 1738 probably under the direction of Gibbs. Of five arches, the central wide and segmental with carved

keystone, the two flanking semi-circular also with carved keystones, the two outer segmental. There is a

balustrade

A baluster () is an upright support, often a vertical moulded shaft, square, or lathe-turned form found in stairways, parapets, and other architectural features. In furniture construction it is known as a spindle. Common materials used in its ...

d

parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an upward extension of a wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/brea ...

, the middle three arches also supporting an open pavilion. Above the central arch this consists of

colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or curv ...

s of four full and two half columns of unfluted Roman Ionic order. Above the flanking arches there are pavilions with arches on all four sides. These have engaged columns on their flanks and ends of the same order as the colonnade which in turn support pediments. The roof is of slate, with an elaborate plaster ceiling. It originally crossed a stream that emptied from the ''Octagon Lake'', and when the lake was enlarged and deepened, made more natural in shape in 1752, this part of the stream became a branch of the lake.

The Saxon Deities

These are sculptures by

John Michael Rysbrack

Johannes Michel or John Michael Rysbrack, original name Jan Michiel Rijsbrack, often referred to simply as Michael Rysbrack (24 June 1694 – 8 January 1770), was an 18th-century Flemish sculptor, who spent most of his career in England where h ...

of the seven deities that gave their names to the days of the week. Carved from

Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone geological formation (formally named the Portland Stone Formation) dating to the Tithonian age of the Late Jurassic that is quarried on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England. The quarries are cut in beds of whi ...

in 1727. They were moved to their present location in 1773. (The sculptures are copies of the originals that were sold in 1921–1922).

For those, like the Grenville family, who followed

Whig politics, the terms 'Saxon' and 'Gothic' represented supposedly English liberties, such as trial by jury.

The sculptures are arranged in a circle. Each sculpture (with the exception of Sunna a half length sculpture) is life size, the base of each statue has a

Runic

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets, known as runic rows, runic alphabets or futharks (also, see '' futhark'' vs ''runic alphabet''), native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were primarily used to represent a sound value (a ...

inscription of the god's name, and stands on a plinth. They are:

Sunna (Sunday),

Mona (Monday),

Tiw (Tuesday),

Woden

Odin (; from ) is a widely revered god in Norse mythology and Germanic paganism. Most surviving information on Odin comes from Norse mythology, but he figures prominently in the recorded history of Northern Europe. This includes the Roman Emp ...

(Wednesday),

Thuner (Thursday),

Friga (Friday) and a Saxon version of

Seatern (Saturday).

The original Sunna & Thuner statues are in the V&A Museum, the original Friga stood for many years in

Portmeirion

Portmeirion (; ) is a folly*

*